#Christopher Clark

Text

Frodo in Rivendell by Christopher Clark

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Clark

Florence Street, 2023

Oil and acrylic on panel

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

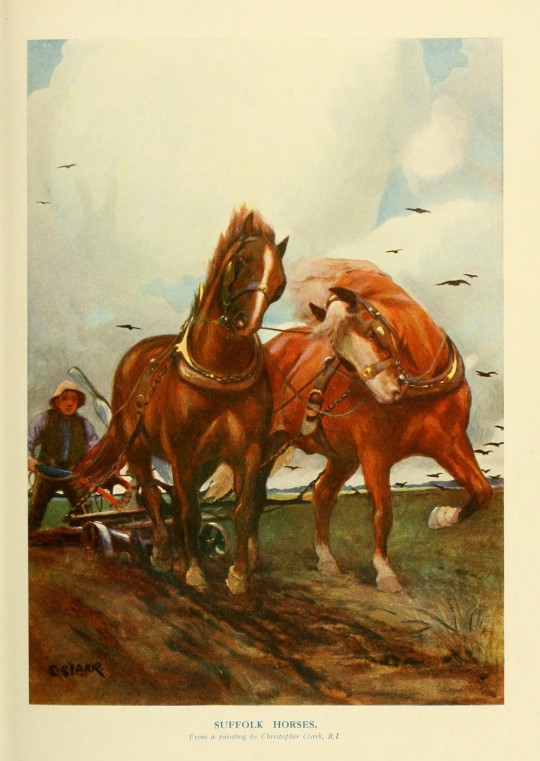

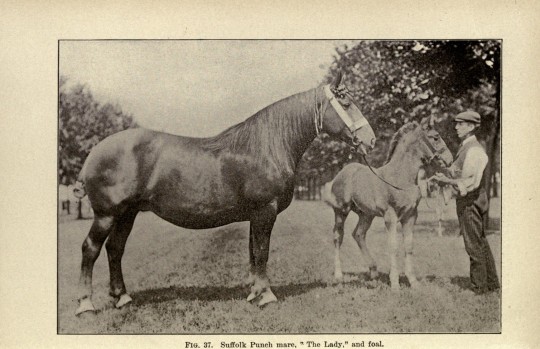

The Suffolk Punch

1. An illustration by F. Babbage of a Suffolk Punch from The horse - its varieties and management in health and disease (1896) a book by George Armatage M. R. C. V. S.

2. Suffolk Sire, Prince Wedgewood an illustration by F. Babbage from The New Book of the Horse (1911) by Charles Richardson.

3. Suffolk Horses from a painting by Christopher Clark, and an illustration in The New Book of the Horse (1911) by Charles Richardson.

4. Suffolk Punch mare "The Lady" and foal a photograph from The Horse, a book by Isaac Phillip Roberts.

(Picture source for illustration 1, Suffolk Sire, Prince Wedgewood, Suffolk Horses, and Suffolk Punch mare "The Lady" and foal)

#Christopher Clark#frank babbage#f. babbage#art#art history#horses#horse#horse art#illustration#Suffolk punch#horse breeds#draft horse#draught horse#old photography

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 88th Foot at the Battle of Salamanca, 1812

by Christopher Clark

#battle of salamanca#art#christopher clark#watercolour#napoleonic wars#peninsular war#europe#european#history#british#english#portuguese#spanish#french#duke of wellington#marshal marmont#salamanca#spain#iberia#napoleonic#auguste de marmont#arthur wellesley#great britain#britain#england#portugal#france#french empire#empire#war

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republicans are decrying the plea deal reached between Hunter Biden and the Department of Justice (DOJ) as a "sweetheart deal" and proof of a double standard in federal prosecutors' treatment of former President Donald Trump—but Trump himself appointed the United States attorney who signed off on the agreement.

The DOJ on Tuesday charged Hunter Biden, the son of President Joe Biden, with failure to pay federal income tax and illegally possessing a weapon. His legal team reached a deal with federal prosecutors that allows him to plead guilty to misdemeanor tax offenses, and he is expected to reach a deal with prosecutors on the felony charge of illegally possessing a firearm as a drug user, the Associated Press reported Tuesday morning.

The deal has sparked criticism from many Republicans, who view the agreement as a slap on the wrist for Hunter Biden while the DOJ has thrown more severe charges at Trump, who pleaded not guilty to 37 charges in the case surrounding whether he improperly stored classified documents, including at least one related to the U.S. military, at his Mar-a-Lago residence. Republicans have claimed the Justice Department has been weaponized against Trump under the Biden administration.

"People are going wild over the Hunter Biden Scam with the DOJ!" Trump wrote in a Truth Social post.

However, U.S. Attorney David Weiss, who offered the agreement to Hunter Biden, was appointed to that position by Trump.

Weiss, the U.S. attorney in Delaware, launched the Hunter Biden probe in 2018 after being appointed to the role by Trump in 2017. The U.S. Senate confirmed his appointment by voice vote in February 2018.

Newly-elected Presidents typically request their predecessors' U.S. attorneys step down when they come into office, but Biden has refrained from removing Weiss over the Hunter Biden investigation, as doing so would likely draw criticism and allegations of trying to interfere in the investigation.

Former U.S. Attorney Gene Rossi told Newsweek in a phone interview that while parts of the deal may be generous to the younger Biden, the fact that a Republican-appointed attorney made the call likely indicates that "politics did not sway the deal either way."

"The decision by Republican U.S. attorney seems to in fact throw cold water on their major argument that this was a sweetheart deal and that they did it to help President Biden's reelection chances," he said.

Still, Rossi said he has never seen a defendant receive only a misdemeanor charge for failing to report taxes worth $3 million but would need to see if Hunter Biden took "any specific acts that he took to either hide, conceal or divert attention" from that $3 million to determine if the deal was "overly generous."

Newsweek reached out to the Trump campaign for comment via email.

Christopher Clark, an attorney for Hunter Biden, told the Associated Press: "I know Hunter believes it is important to take responsibility for these mistakes he made during a period of turmoil and addiction in his life. He looks forward to continuing his recovery and moving forward."

Karoline Leavitt, the spokesperson for the Trump-aligned Make America Great Again Inc. super PAC, slammed the deal in a statement posted to Twitter.

"As President Trump predicted, Biden's Justice Department is cutting a sweetheart deal with Hunter Biden in order to make their bogus case to 'Get Trump' appear fair," Leavitt tweeted. "Meanwhile, Biden's DOJ continues to turn a blind eye to the Biden family's extensive corruption and bribery scheme. The American people need President Trump back in office to appoint a truly independent special prosecutor that will finally bring justice."

#us politics#news#newsweek#republicans#donald trump#conservatives#hunter biden#biden administration#president joe biden#department of justice#tax evasion#illegal possession of a firearm#the associated press#David Weiss#trump administration#2023#Gene Rossi#Christopher Clark#Karoline Leavitt

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

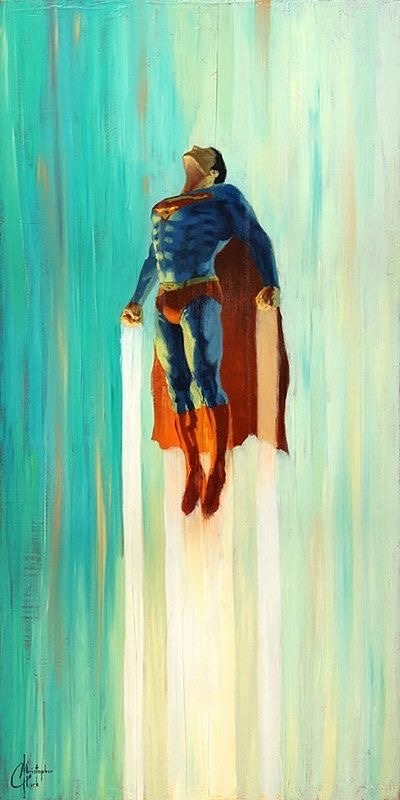

Art Credit to Christopher Clark

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 May 2023: Time Period

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rookie feds spoilers

•

•

•

•

•

#the rookie spoilers#the rookie feds spoilers#the rookie#the rookie abc#the rookie feds#john nolan#therookie rambles#simone clark#christopher clark

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Clark

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endor Space Battle by Christopher Clark

I saw this painting of the Millennium Falcon fighting above the planet Endor frm Return of the Jedi on my Instagram feed.

Painted by Christopher Clark, who is a long time ACME Archives collaborator and has a lot of Star Wars art under his belt. As with the other Millennium Falcon paintings that Christopher has done, his strength lies in his use of vibrant light and colour to bring them alive and…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Böses Erwachen

Raphaela Edelbauers »Die Inkommensurablen« ist ein Vorkriegs- und Post-Corona-Roman in einem. Das lässt an die Ukraine denken, führt aber ins k.u.k.-Österreich anno 1914.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#Christopher Clark#Clemens J. Setz#Deutscher Buchpreis#featured#Joseph Roth#Österreichischer Buchpreis#Raphaela Edelbauer#Robert Musil#Stefan Zweig

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rewatched 1978 Superman and remembered how much of a total dreamboat Christopher Reeve is, both as Clark Kent and Superman.

#my art#superman#clark kent#dc comics#fanart#character design#he's two flavors of himbo in one man#maybe my only celeb crush. rip christopher reeve#i'm hardly a superhero fan but imo new superman stuff needs to learn more into him also being a klutzy loser officer worker in his 30s

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Clark

Cradle of Civilization, 2017

Oil on panel

85 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Abigail Green

When we think of the revolutions of 1848 we see them in Technicolor. There are people, crowds and crowds of people caught in moments of intense activity; and behind them there are the immediately recognizable cityscapes of nineteenth-century Europe – Paris, Venice, Vienna and Berlin; and always there are the flags. The red flag of revolution and the tricolours of nationalism: black-red-and-gold, green-white-and-red, red-white-and-blue. It’s like a theatrical production, at once operatic and dramatic, playing out before us on a vast, pan-continental stage. Christopher Clark’s extraordinary new history of 1848 shows us something different, right from the cover illustration. Not crowds, but the menacing emptiness that lies between the barricades of a Paris street when you hope for the best, fear for the worst and hide from the gunfire. Not colour, but a brooding, hazy, sepia-tinted world in which the protagonists are barely discernible. We know they are there, but we can’t see them, not quite; yet, if we look really closely, we can see that “everything and everyone was in motion”.

Even before the revolutions this was a moment of dislocation. Nowadays a historian might call it a polycrisis. All across Europe the nature of work and of property was changing, agriculture and landholding practices were in a state of upheaval, and social conflicts broke out – often violent, always unsettling, and driven, Clark tells us, by “competition over every conceivable resource in a world marked by scarcity and low rates of productivity growth”. Some of these crises are familiar: the revolts of the Lyon canuts (1834) and the Silesian weavers (1844), the Irish potato famine (beginning in 1845) and the Galician massacres of 1846. Others are more or less unknown, like the Pyrenean Guerre des Demoiselles (1829–31), in which peasant men dressed as women, the better to resist attempts by the authorities to deny their traditional access to the forest and its resources. What matters is that contemporaries knew them – and wrote about them. This was an era in which members of the new bourgeois classes began to direct a voyeuristic, moralistic and statistically inclined eye on the appalling conditions of their compatriots. In the age that preceded the tenement block, poverty had a different quality: it transpired that in places as unlike as Vienna and Nantes, those at the bottom of the social pile lived – literally – in sewers beneath the ground, which they wandered barefoot and in rags.

Clark emphasizes that there was no direct causal nexus between all this and the outbreak of revolution in 1848. The geographies of insurrection and acute poverty never really converged, because fighting for a new world was hardly top of the agenda for the truly desperate. (This, of course, we have known for a long time.) Invariably, however, hunger was political. And in an age of transition – when terms such as “liberalism”, “socialism” and “conservatism” were only just entering the lexicon – politics, too, was changing.

The society brought to life in Revolutionary Spring thrills with unexpected energy. Clark speaks the language of liberal moderation, of political radicalism, of religion and of patriotism in ways that capture something of the glamour that infused them at the time. Here we find the subversive magic of the market as a space of equal and free exchange in a Europe marked by feudal and monarchical power; the infatuation of democratic and socialist radicals with the prospect of social harmony (a prospect liberals, even then, knew to be as fantastical as the Icarian socialist vision of a banquet at which all classes could eat their fill peaceably, together – in contrast to the real but much more socially divisive political banquets that were very much a feature of this era); and the spiritual radiance with which nationalists such as the novelist and poet Adam Mickiewicz infused his Books of the Polish Nation (1832) and invoked the sufferings of a martyred people. “Religion is flowing through this text”, Clark writes, “but it is not the religion Europeans learned from their priests.” Faith and the language of religious tradition had not lost their power to transfigure the political, but danger lurked in a world where “religious sentiment had got unstuck from religious authority”.

These decades saw the emergence of a new class of politician: the professional revolutionary. Contemporaries obsessed over the threat posed by clandestine networks, and there certainly seemed to be plenty of them. In early-nineteenth-century Geneva, Filippo Buonarroti, a veteran of the 1790s, established the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits, an esoteric network dedicated to “the republicanization of the whole of Europe”, which operated under the cover of freemasonry. During the 1830s the German dramatist Georg Büchner fled Hesse after publishing a visionary call to arms that horrified the authorities with its oblique references to an (entirely imaginary) insurrectionary network composed of “messengers of the Lord”. The socialist Louis Auguste Blanqui, a “lifelong revolutionary and orchestrator of clandestine networks”, spent thirty-three years as the prisoner of a series of repressive (if ideologically disparate) French regimes.

Then there was the quintessential nationalist, Giuseppe Mazzini – the most wanted man in continental Europe. He was a deeply charismatic figure whom the American journalist Margaret Fuller described as “by far the most beauteous man” she had ever seen; a visionary who, as Carlo Cattaneo put it, “considered disasters victories, provided that one fought”. As an insurrectionary Mazzini was a perennial failure, but his genius for publicity was unparalleled. The glamour attached to such figures distracted the authorities from the more humdrum realities of political dissent, social unrest and severe economic dislocation that were undermining their world from within.

Where, then, did the dam burst? Arguably the first cracks appeared in Switzerland. It was here, in 1847, that a conflict between the leadership of the Swiss confederation and a small group of dissident Catholic cantons, determined to assert their democratic right to readmit the Jesuits, spilled over into a short but by no means bloodless civil war. Contemporaries on all sides read it as a “test case in the struggle between revolution and reaction”, to cite one diplomatic report. After that came Sicily, a polity that had been seething with upheaval for the best part of thirty years. It was here that the insurgents of 1848 first tasted victory, when a small, chaotic uprising in Palermo rapidly escalated into something more: violent, disparate and uncontrollable, disrupting the established order in both city and countryside. And then, of course, there was France.

Generations of historians have cast the revolutions as a wave that swept over Europe, with Paris at the epicentre. When the German-Jewish writer Fanny Lewald set out to experience the revolution first hand, she headed inevitably for the French capital, a city she described as Europe’s “perennially beating heart”. That narrative replicates the “France first” model of political modernity to which 1789 gave birth. Chroniclers of 1848 have struggled to escape this model because to describe the collapse of regimes across Europe is to describe something that looks remarkably like a domino effect. Writing twenty-five years ago, the German historian Dieter Langewiesche argued that 1848 was not merely a repeat of the 1790s. It was instead something qualitatively new: a single, pan-continental news event that united levels of experience previously separated – the provincial, the national and the European. In this way the revolutions Europeanized politics, even as they politicized Europe. The upshot was a phenomenon that Langewiesche termed “Kommunikationsraum Europa”.

Clark, too, stresses the Europeanness of that moment. The concise, epigrammatic brilliance of Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire – still the most influential account of the revolutions – was predicated on a clear national focus, just as the brevity of Lewis Namier’s elegant analysis of 1944 depended on his preoccupation with central Europe. What we have here is a qualitatively different undertaking: a panoramic account, stretching from Portugal to the Ionian Islands, of a set of interconnected societies caught between unravelling and beginning. It is a new kind of decentred European history, one that rides roughshod over established narrative and geopolitical hierarchies.

Of course, unrest did propagate outwards, as the capitals of the most important states on the continent became “nodal points of high instability”. Yet the reality was more complex than this implies. The “revolutions” of 1848 were neither directly linked nor independent, but “cognate, rooted in the same interconnected economic space, unfolding within kindred cultural and political orders, and precipitated by processes of socio-political and ideational change that had always been transnationally connected”.

That perception of a continent-wide upheaval was widely shared by contemporaries before – as well as after – the event. The radical republicans of the Parisian daily La Réforme, who soon found themselves helping to run the French Provisional Government; Marx and Engels, for whom the spectre of communism haunted Europe and not its constituent states; the conservative voices behind El Heraldo, close to the moderado regime in Spain; and the editors of smaller, less well-resourced publications such as the Finnish-language Suometar, the Hungarian Gazeta de Transilvania and the Curierul Românesc, all of which continually filleted and republished each other’s stories: all were “informed about the advancing frontier of political unrest and in a good position to recognize its trans-European character”. Nor did statesmen like François Guizot or Clemens von Metternich demur. In short, it hardly matters if the revolution – simultaneously a singular and a plural phenomenon – began in Sicily, Switzerland or France. For all over Europe there were precipitants and there were long-term socio-economic causes. Everywhere the “time of politics” was accelerating as capital cities, provincial towns and their rural hinterlands began marching to a different beat.

This is narrative history in the grand style, and Clark does not neglect the great set pieces. If you want the February revolution, the fall of Metternich, the Five Days of Milan, you will find them vividly rendered here in a prose that interlaces deep learning with deliberate anachronism. This might seem gimmicky; in fact it is oddly effective, because it forces us to question what we thought we knew. Whether we are talking about the “Dolce & Gabbana” glamour of that legendary Risorgimento leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, or the Tahrir Square-like qualities of revolutionary spaces from the Piazza del Quirinale in Rome, through the Landhaus courtyard in Vienna, to the Schlossplatz in Berlin: all places of emotion and awakening, “where the distance between people is abolished” (in the words of a popular Egyptian song of 2011).

But in the spring of 1848 – as Clark notes – the story fractures. Alongside the set pieces something deeper emerges: a thematically constructed, comparative narrative that is, at the same time, a highly sophisticated work of analysis. “Honour Your Dead”. “Establish a Government”. “Elect a Parliament”. “Draft a Constitution”. Always, the author sets the obvious against the unfamiliar. France against the Romanian Principalities. Denmark against Piedmont. The Sicilian parliament against the German National Assembly. Occasionally he stands aside to ask about other places and experiences: Black 1848, Global 1848 and the Dogs That Didn’t Bark.

Much of this is replete with insight. If you thought legal history was boring, Clark will persuade you otherwise. Infused with the hallucinatory language of the defrocked priest Félicité de Lamennais, the constitutions drafted in the white heat of revolution were not “dry, cookie-cutter statutes cribbed from a common template”, but “highly idiosyncratic documents in which monarchical or republican elites spoke directly to the masses of the governed”.

Did you think that Britain and Belgium were spared revolution because the appetite of their populations for social and political reform was sated? Clark will draw your attention to the strong arm of the state in these supposedly liberal havens. One hundred and fifty thousand Chartists met at Kennington Common on April 10, 1848; they were held at bay by 4,000 police, 12,000 troops (held in reserve) and 85,000 “club-wielding” volunteers. The Prussians were so impressed that they sent one of their best men to tour London and the provinces, and see what he could learn.

Or perhaps you thought of the revolutions as the pivot around which the great transatlantic age of emancipations turned? Clark shows instead how the power of words such as “emancipation” and “slavery” has served to elide experiences that were, in fact, unlike. The situation of peasants differed, when it came to rights, from that of enslaved people, Jews, women and the “Roma Slaves” of eastern Europe. All these groups aspired to “freedom” (though rarely with one voice), but for many reasons their histories have remained distinct. Racism, sexism and “the peculiar predicament of the Jews, in which theology, eschatology, xenophobia and social anxiety blended to create a remarkably resilient form of suspicion and hatred” – these three rationales of discrimination were not functions of each other, but “separate fundaments, so deeply built into modern European culture that they seemed primordial, natural, ordained by God”.

Then as now, the plight of outcast groups haunted the imagination of Europe’s cultural elites. In reality, however, the vaunted “age of emancipation” always amounted to less than the sum of its parts. Jews and Roma briefly became citizens, only to experience repeated cycles of rejection and inclusion, culminating in both cases in genocide. Slavery was abolished – apparently from the metropole, but in colonies such as Martinique and Guadeloupe enslaved people did not hesitate to take matters into their own hands, setting an example that those on the nearby Dutch islands of the Lesser Antilles soon followed. But liberty can be “granted in principle without being enjoyed in fact”. Most former slaves remained in their place of employment, even if they insisted on the right to grow vegetables for their own use, to treat their traditional houses as private property or to work for different masters. As for women, they only really began to achieve political rights during the First World War, and many decades later in the homeland of revolution: France.

The focus in this review on causes rather than consequences reflects the balance of a narrative that is richer, and less compressed, at the beginning than the end. Not that the ending was unimportant. Repeatedly, and in a wide variety of contexts, Clark stresses that 1848 cannot be dismissed as a failure. Rather, the multitude of questions that underpinned the revolutions – “about democracy, representation, social equality, the organization of labour, gender relations, religion, forms of state power” – render them too complex and diffuse an episode to be understood in such terms. They were chaotic, but they were also deeply consequential. They changed the way contemporaries – all of them – read and sought to navigate the world.

As Clark tells it, there are periods, including the Cold War, whose “signature is stabilization”; and there are periods, like our own age, marked by “flux and transition, where the direction of travel is harder to discern, when disparate forms of identity and commitment become unpredictably enmeshed with each other”. That insight lies at the heart of this book, which repeatedly makes a connection between then and now. All history, of course, is written in the present, but as we watch public transport grind to a halt in Germany, flag-waving Israelis demonstrate en masse in defence of the judiciary and France subsumed (yet again) in a wave of violent protest, fed simultaneously by the left and the right, we may feel he has a point.

Part of the charm of this superb book lies in its ability to juxtapose the celebrated with the forgotten. We remember Marx and Mazzini; some of us have even heard of the utopian cult that coalesced around the ideas of Saint-Simon and the abolitionism of the Frenchman Victor Schoelcher. But who now knows the radical Parisian journalist Claire Démar? For her, patriarchy – not monarchy, religion or capital – was the “monstrous power” that underpinned the inequality of all humans: the power of fathers to beat their sons and of husbands to beat, rape and dispossess their wives. She would commit suicide shortly after committing these thoughts to paper. Both her feminism and her tragic end surely render Démar a heroine ripe for rediscovery.

The same could hardly be said of the poet, essayist and proud Illyrian patriot Dragojla Jarnević – a woman born and bred in German-speaking Croatia, who rejected the Kultursprache of her childhood for a language she could hardly speak, which she came to embrace as “my mother tongue”. Nationalism is less popular than it once was in the chattering classes. But Jarnević’s life speaks to aspects of our own society – the ability of men and women to construct new identities and to articulate them in biological and ideologically laden terms.

One hundred and seventy-five years later the revolutions seem to have long since receded into history. Yet it is common nowadays for citizens of the twenty-first century to find ways of connecting imaginatively to the mid-nineteenth-century past. The internet is awash with stories of those nurtured in multigenerational families, for whom the lived experience of slavery feels almost within touching distance. The descendants of slave owners have likewise begun to acknowledge an emotional (and financial) connection to that horrific history. In short, Clark is right to remind us that the revolutions of 1848 are less distant than we think.

In Italian it is still possible to fare un quarantotto. Not coincidentally, perhaps, it was an Italian-Israeli who texted me from Jerusalem to say that she felt as if she were reliving the “1848 barricades, shouting basic liberal values”. Only the other day, at an event largely attended by elderly central European refugees, I met a historian who described himself as both a Catholic and a Jew – proudly asserting his descent (on the Catholic side) from a soldier who lost an arm at the Battle of Custoza, fighting under Field Marshal Radetzky for the Habsburgs in 1848. Politically and personally these genealogies have become hopelessly entangled, but there is a sense in which we are all – particularly in Europe – children of 1848.

0 notes

Link

By Abigail Green

When we think of the revolutions of 1848 we see them in Technicolor. There are people, crowds and crowds of people caught in moments of intense activity; and behind them there are the immediately recognizable cityscapes of nineteenth-century Europe – Paris, Venice, Vienna and Berlin; and always there are the flags. The red flag of revolution and the tricolours of nationalism: black-red-and-gold, green-white-and-red, red-white-and-blue. It’s like a theatrical production, at once operatic and dramatic, playing out before us on a vast, pan-continental stage. Christopher Clark’s extraordinary new history of 1848 shows us something different, right from the cover illustration. Not crowds, but the menacing emptiness that lies between the barricades of a Paris street when you hope for the best, fear for the worst and hide from the gunfire. Not colour, but a brooding, hazy, sepia-tinted world in which the protagonists are barely discernible. We know they are there, but we can’t see them, not quite; yet, if we look really closely, we can see that “everything and everyone was in motion”.

Even before the revolutions this was a moment of dislocation. Nowadays a historian might call it a polycrisis. All across Europe the nature of work and of property was changing, agriculture and landholding practices were in a state of upheaval, and social conflicts broke out – often violent, always unsettling, and driven, Clark tells us, by “competition over every conceivable resource in a world marked by scarcity and low rates of productivity growth”. Some of these crises are familiar: the revolts of the Lyon canuts (1834) and the Silesian weavers (1844), the Irish potato famine (beginning in 1845) and the Galician massacres of 1846. Others are more or less unknown, like the Pyrenean Guerre des Demoiselles (1829–31), in which peasant men dressed as women, the better to resist attempts by the authorities to deny their traditional access to the forest and its resources. What matters is that contemporaries knew them – and wrote about them. This was an era in which members of the new bourgeois classes began to direct a voyeuristic, moralistic and statistically inclined eye on the appalling conditions of their compatriots. In the age that preceded the tenement block, poverty had a different quality: it transpired that in places as unlike as Vienna and Nantes, those at the bottom of the social pile lived – literally – in sewers beneath the ground, which they wandered barefoot and in rags.

Clark emphasizes that there was no direct causal nexus between all this and the outbreak of revolution in 1848. The geographies of insurrection and acute poverty never really converged, because fighting for a new world was hardly top of the agenda for the truly desperate. (This, of course, we have known for a long time.) Invariably, however, hunger was political. And in an age of transition – when terms such as “liberalism”, “socialism” and “conservatism” were only just entering the lexicon – politics, too, was changing.

The society brought to life in Revolutionary Spring thrills with unexpected energy. Clark speaks the language of liberal moderation, of political radicalism, of religion and of patriotism in ways that capture something of the glamour that infused them at the time. Here we find the subversive magic of the market as a space of equal and free exchange in a Europe marked by feudal and monarchical power; the infatuation of democratic and socialist radicals with the prospect of social harmony (a prospect liberals, even then, knew to be as fantastical as the Icarian socialist vision of a banquet at which all classes could eat their fill peaceably, together – in contrast to the real but much more socially divisive political banquets that were very much a feature of this era); and the spiritual radiance with which nationalists such as the novelist and poet Adam Mickiewicz infused his Books of the Polish Nation (1832) and invoked the sufferings of a martyred people. “Religion is flowing through this text”, Clark writes, “but it is not the religion Europeans learned from their priests.” Faith and the language of religious tradition had not lost their power to transfigure the political, but danger lurked in a world where “religious sentiment had got unstuck from religious authority”.

These decades saw the emergence of a new class of politician: the professional revolutionary. Contemporaries obsessed over the threat posed by clandestine networks, and there certainly seemed to be plenty of them. In early-nineteenth-century Geneva, Filippo Buonarroti, a veteran of the 1790s, established the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits, an esoteric network dedicated to “the republicanization of the whole of Europe”, which operated under the cover of freemasonry. During the 1830s the German dramatist Georg Büchner fled Hesse after publishing a visionary call to arms that horrified the authorities with its oblique references to an (entirely imaginary) insurrectionary network composed of “messengers of the Lord”. The socialist Louis Auguste Blanqui, a “lifelong revolutionary and orchestrator of clandestine networks”, spent thirty-three years as the prisoner of a series of repressive (if ideologically disparate) French regimes.

Then there was the quintessential nationalist, Giuseppe Mazzini – the most wanted man in continental Europe. He was a deeply charismatic figure whom the American journalist Margaret Fuller described as “by far the most beauteous man” she had ever seen; a visionary who, as Carlo Cattaneo put it, “considered disasters victories, provided that one fought”. As an insurrectionary Mazzini was a perennial failure, but his genius for publicity was unparalleled. The glamour attached to such figures distracted the authorities from the more humdrum realities of political dissent, social unrest and severe economic dislocation that were undermining their world from within.

Where, then, did the dam burst? Arguably the first cracks appeared in Switzerland. It was here, in 1847, that a conflict between the leadership of the Swiss confederation and a small group of dissident Catholic cantons, determined to assert their democratic right to readmit the Jesuits, spilled over into a short but by no means bloodless civil war. Contemporaries on all sides read it as a “test case in the struggle between revolution and reaction”, to cite one diplomatic report. After that came Sicily, a polity that had been seething with upheaval for the best part of thirty years. It was here that the insurgents of 1848 first tasted victory, when a small, chaotic uprising in Palermo rapidly escalated into something more: violent, disparate and uncontrollable, disrupting the established order in both city and countryside. And then, of course, there was France.

Generations of historians have cast the revolutions as a wave that swept over Europe, with Paris at the epicentre. When the German-Jewish writer Fanny Lewald set out to experience the revolution first hand, she headed inevitably for the French capital, a city she described as Europe’s “perennially beating heart”. That narrative replicates the “France first” model of political modernity to which 1789 gave birth. Chroniclers of 1848 have struggled to escape this model because to describe the collapse of regimes across Europe is to describe something that looks remarkably like a domino effect. Writing twenty-five years ago, the German historian Dieter Langewiesche argued that 1848 was not merely a repeat of the 1790s. It was instead something qualitatively new: a single, pan-continental news event that united levels of experience previously separated – the provincial, the national and the European. In this way the revolutions Europeanized politics, even as they politicized Europe. The upshot was a phenomenon that Langewiesche termed “Kommunikationsraum Europa”.

Clark, too, stresses the Europeanness of that moment. The concise, epigrammatic brilliance of Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire – still the most influential account of the revolutions – was predicated on a clear national focus, just as the brevity of Lewis Namier’s elegant analysis of 1944 depended on his preoccupation with central Europe. What we have here is a qualitatively different undertaking: a panoramic account, stretching from Portugal to the Ionian Islands, of a set of interconnected societies caught between unravelling and beginning. It is a new kind of decentred European history, one that rides roughshod over established narrative and geopolitical hierarchies.

Of course, unrest did propagate outwards, as the capitals of the most important states on the continent became “nodal points of high instability”. Yet the reality was more complex than this implies. The “revolutions” of 1848 were neither directly linked nor independent, but “cognate, rooted in the same interconnected economic space, unfolding within kindred cultural and political orders, and precipitated by processes of socio-political and ideational change that had always been transnationally connected”.

That perception of a continent-wide upheaval was widely shared by contemporaries before – as well as after – the event. The radical republicans of the Parisian daily La Réforme, who soon found themselves helping to run the French Provisional Government; Marx and Engels, for whom the spectre of communism haunted Europe and not its constituent states; the conservative voices behind El Heraldo, close to the moderado regime in Spain; and the editors of smaller, less well-resourced publications such as the Finnish-language Suometar, the Hungarian Gazeta de Transilvania and the Curierul Românesc, all of which continually filleted and republished each other’s stories: all were “informed about the advancing frontier of political unrest and in a good position to recognize its trans-European character”. Nor did statesmen like François Guizot or Clemens von Metternich demur. In short, it hardly matters if the revolution – simultaneously a singular and a plural phenomenon – began in Sicily, Switzerland or France. For all over Europe there were precipitants and there were long-term socio-economic causes. Everywhere the “time of politics” was accelerating as capital cities, provincial towns and their rural hinterlands began marching to a different beat.

This is narrative history in the grand style, and Clark does not neglect the great set pieces. If you want the February revolution, the fall of Metternich, the Five Days of Milan, you will find them vividly rendered here in a prose that interlaces deep learning with deliberate anachronism. This might seem gimmicky; in fact it is oddly effective, because it forces us to question what we thought we knew. Whether we are talking about the “Dolce & Gabbana” glamour of that legendary Risorgimento leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, or the Tahrir Square-like qualities of revolutionary spaces from the Piazza del Quirinale in Rome, through the Landhaus courtyard in Vienna, to the Schlossplatz in Berlin: all places of emotion and awakening, “where the distance between people is abolished” (in the words of a popular Egyptian song of 2011).

But in the spring of 1848 – as Clark notes – the story fractures. Alongside the set pieces something deeper emerges: a thematically constructed, comparative narrative that is, at the same time, a highly sophisticated work of analysis. “Honour Your Dead”. “Establish a Government”. “Elect a Parliament”. “Draft a Constitution”. Always, the author sets the obvious against the unfamiliar. France against the Romanian Principalities. Denmark against Piedmont. The Sicilian parliament against the German National Assembly. Occasionally he stands aside to ask about other places and experiences: Black 1848, Global 1848 and the Dogs That Didn’t Bark.

Much of this is replete with insight. If you thought legal history was boring, Clark will persuade you otherwise. Infused with the hallucinatory language of the defrocked priest Félicité de Lamennais, the constitutions drafted in the white heat of revolution were not “dry, cookie-cutter statutes cribbed from a common template”, but “highly idiosyncratic documents in which monarchical or republican elites spoke directly to the masses of the governed”.

Did you think that Britain and Belgium were spared revolution because the appetite of their populations for social and political reform was sated? Clark will draw your attention to the strong arm of the state in these supposedly liberal havens. One hundred and fifty thousand Chartists met at Kennington Common on April 10, 1848; they were held at bay by 4,000 police, 12,000 troops (held in reserve) and 85,000 “club-wielding” volunteers. The Prussians were so impressed that they sent one of their best men to tour London and the provinces, and see what he could learn.

Or perhaps you thought of the revolutions as the pivot around which the great transatlantic age of emancipations turned? Clark shows instead how the power of words such as “emancipation” and “slavery” has served to elide experiences that were, in fact, unlike. The situation of peasants differed, when it came to rights, from that of enslaved people, Jews, women and the “Roma Slaves” of eastern Europe. All these groups aspired to “freedom” (though rarely with one voice), but for many reasons their histories have remained distinct. Racism, sexism and “the peculiar predicament of the Jews, in which theology, eschatology, xenophobia and social anxiety blended to create a remarkably resilient form of suspicion and hatred” – these three rationales of discrimination were not functions of each other, but “separate fundaments, so deeply built into modern European culture that they seemed primordial, natural, ordained by God”.

Then as now, the plight of outcast groups haunted the imagination of Europe’s cultural elites. In reality, however, the vaunted “age of emancipation” always amounted to less than the sum of its parts. Jews and Roma briefly became citizens, only to experience repeated cycles of rejection and inclusion, culminating in both cases in genocide. Slavery was abolished – apparently from the metropole, but in colonies such as Martinique and Guadeloupe enslaved people did not hesitate to take matters into their own hands, setting an example that those on the nearby Dutch islands of the Lesser Antilles soon followed. But liberty can be “granted in principle without being enjoyed in fact”. Most former slaves remained in their place of employment, even if they insisted on the right to grow vegetables for their own use, to treat their traditional houses as private property or to work for different masters. As for women, they only really began to achieve political rights during the First World War, and many decades later in the homeland of revolution: France.

The focus in this review on causes rather than consequences reflects the balance of a narrative that is richer, and less compressed, at the beginning than the end. Not that the ending was unimportant. Repeatedly, and in a wide variety of contexts, Clark stresses that 1848 cannot be dismissed as a failure. Rather, the multitude of questions that underpinned the revolutions – “about democracy, representation, social equality, the organization of labour, gender relations, religion, forms of state power” – render them too complex and diffuse an episode to be understood in such terms. They were chaotic, but they were also deeply consequential. They changed the way contemporaries – all of them – read and sought to navigate the world.

As Clark tells it, there are periods, including the Cold War, whose “signature is stabilization”; and there are periods, like our own age, marked by “flux and transition, where the direction of travel is harder to discern, when disparate forms of identity and commitment become unpredictably enmeshed with each other”. That insight lies at the heart of this book, which repeatedly makes a connection between then and now. All history, of course, is written in the present, but as we watch public transport grind to a halt in Germany, flag-waving Israelis demonstrate en masse in defence of the judiciary and France subsumed (yet again) in a wave of violent protest, fed simultaneously by the left and the right, we may feel he has a point.

Part of the charm of this superb book lies in its ability to juxtapose the celebrated with the forgotten. We remember Marx and Mazzini; some of us have even heard of the utopian cult that coalesced around the ideas of Saint-Simon and the abolitionism of the Frenchman Victor Schoelcher. But who now knows the radical Parisian journalist Claire Démar? For her, patriarchy – not monarchy, religion or capital – was the “monstrous power” that underpinned the inequality of all humans: the power of fathers to beat their sons and of husbands to beat, rape and dispossess their wives. She would commit suicide shortly after committing these thoughts to paper. Both her feminism and her tragic end surely render Démar a heroine ripe for rediscovery.

The same could hardly be said of the poet, essayist and proud Illyrian patriot Dragojla Jarnević – a woman born and bred in German-speaking Croatia, who rejected the Kultursprache of her childhood for a language she could hardly speak, which she came to embrace as “my mother tongue”. Nationalism is less popular than it once was in the chattering classes. But Jarnević’s life speaks to aspects of our own society – the ability of men and women to construct new identities and to articulate them in biological and ideologically laden terms.

One hundred and seventy-five years later the revolutions seem to have long since receded into history. Yet it is common nowadays for citizens of the twenty-first century to find ways of connecting imaginatively to the mid-nineteenth-century past. The internet is awash with stories of those nurtured in multigenerational families, for whom the lived experience of slavery feels almost within touching distance. The descendants of slave owners have likewise begun to acknowledge an emotional (and financial) connection to that horrific history. In short, Clark is right to remind us that the revolutions of 1848 are less distant than we think.

In Italian it is still possible to fare un quarantotto. Not coincidentally, perhaps, it was an Italian-Israeli who texted me from Jerusalem to say that she felt as if she were reliving the “1848 barricades, shouting basic liberal values”. Only the other day, at an event largely attended by elderly central European refugees, I met a historian who described himself as both a Catholic and a Jew – proudly asserting his descent (on the Catholic side) from a soldier who lost an arm at the Battle of Custoza, fighting under Field Marshal Radetzky for the Habsburgs in 1848. Politically and personally these genealogies have become hopelessly entangled, but there is a sense in which we are all – particularly in Europe – children of 1848.

0 notes

Text

"FREIHEUT. Handbuch für den Tiger in dir" von Monika Donner. Rezension

Viele Menschen wähnen sich als durchaus in Freiheit lebend. „Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit“ tönt es im „Lied der Deutschen“. Wie frei aber sind wir wirklich? Setzten wir uns einmal ruhig hin und ließen es uns einmal genau durch den Kopf gehen, stellten wir – wären wir ehrlich zu uns – mehr und mehr fest, dass es mit unserer Freiheit soweit nicht her ist. Erinnern wir uns doch nur an die…

View On WordPress

#christopher clark#Corona#Emil Luchardt#Halford John Mackinder#Michael Hüther#Monika Donner#Monithor#Rainer Mausfeld#Wikipedia

0 notes