#gongbi painting

Text

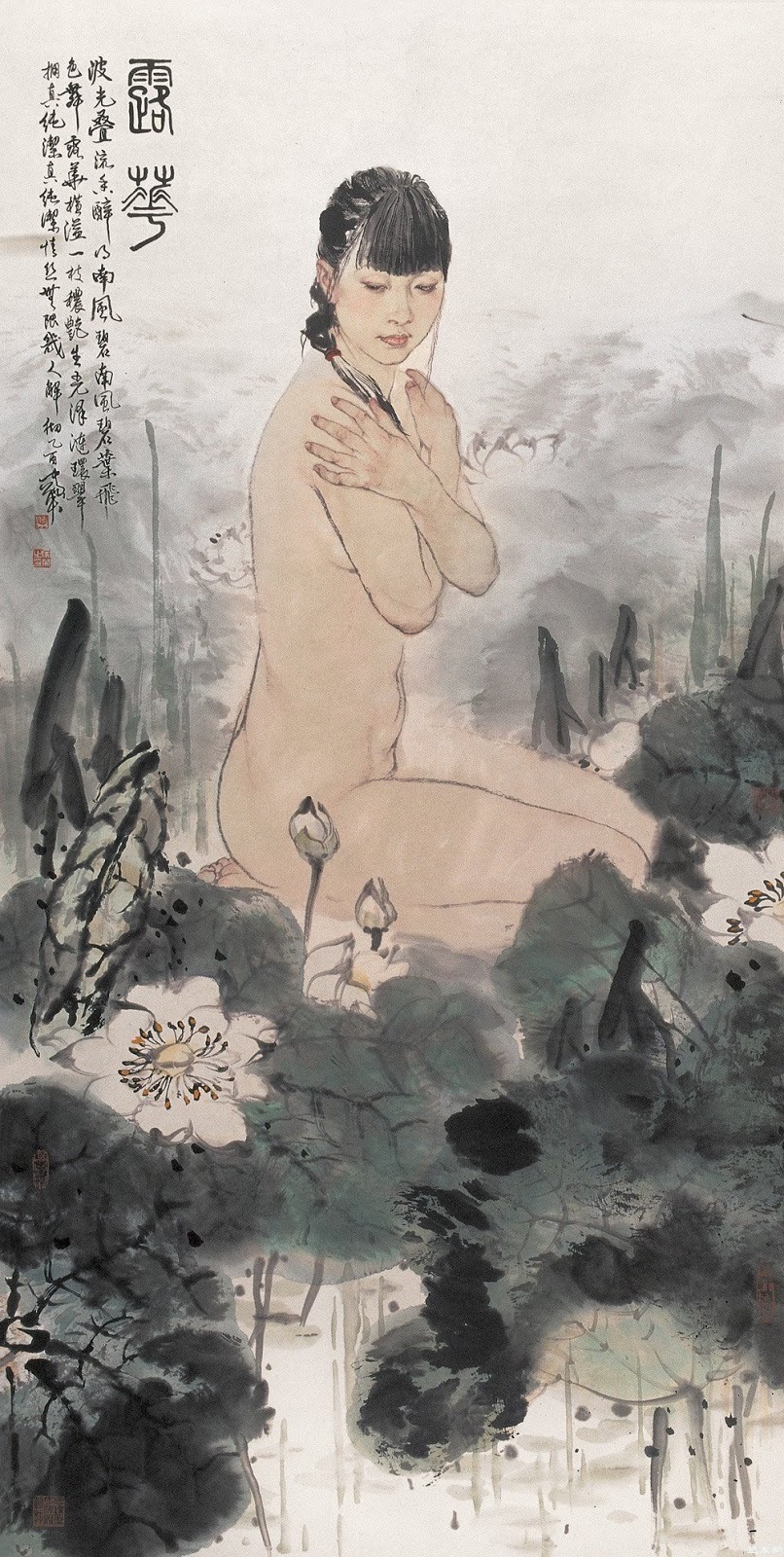

Meet He Jiaying, A Celebrated Chinese Artist And Educator Specializing In Gongbi Painting

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

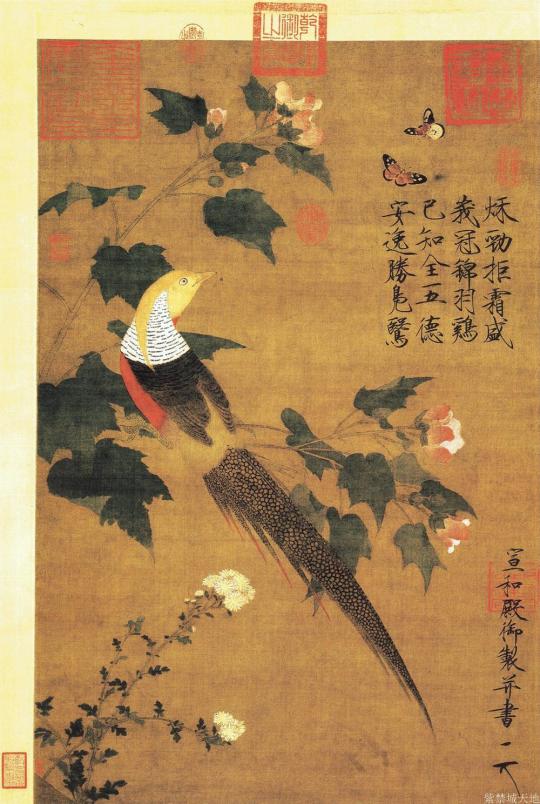

Emperor Huizong of Song (Chinese) • Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers with Butterflies (gongbi painting) • 11th century

The name "gongbi" is from the Chinese "gong jin", meaning 'tidy' (meticulous brush craftsmanship). The gongbi technique uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimits details very precisely and without independent or expressive variation.

#still life#art#chinese art#11th century chinese art#painting#gongbi painting#art of the still life blog#emperor huizong of song

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

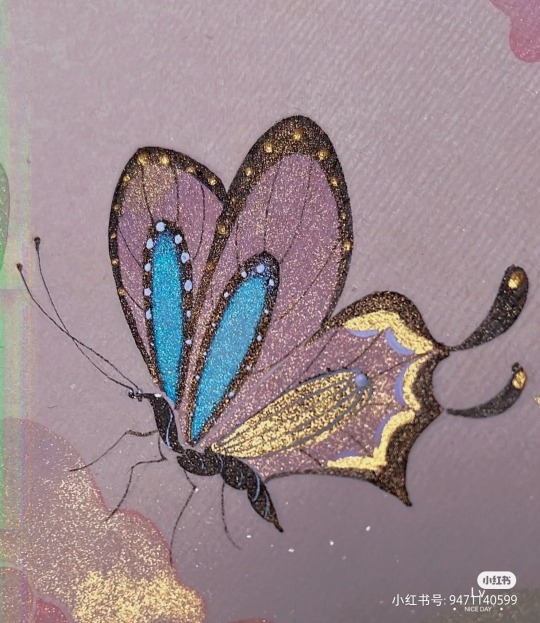

chinese gongbi style by 长安(xiaohongshu: 9471140599)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pigeon on a Peach Branch by Emperor Huizong (1108)

#art#asian art#chinese art#artwork#art style#pigeon#pigeon on a peach branch#emperor huizong#gongbi#gongbi style#bird and flower#bird and flower painting#bird art#birds#slavic roots western mind#northern song dynasty#song dynasty#northern song dynasty art#artblr

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

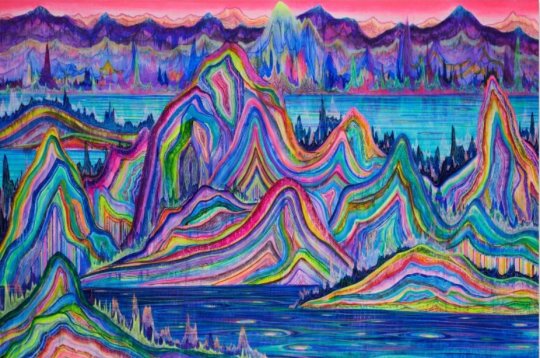

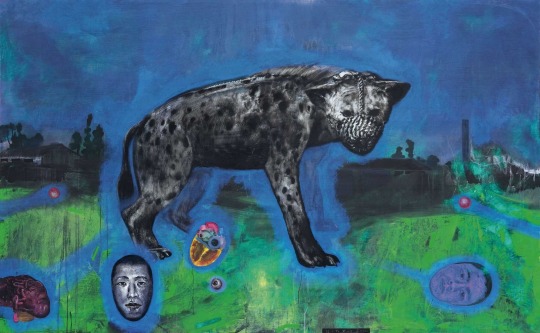

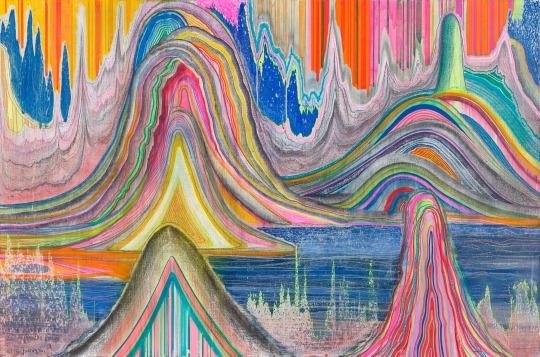

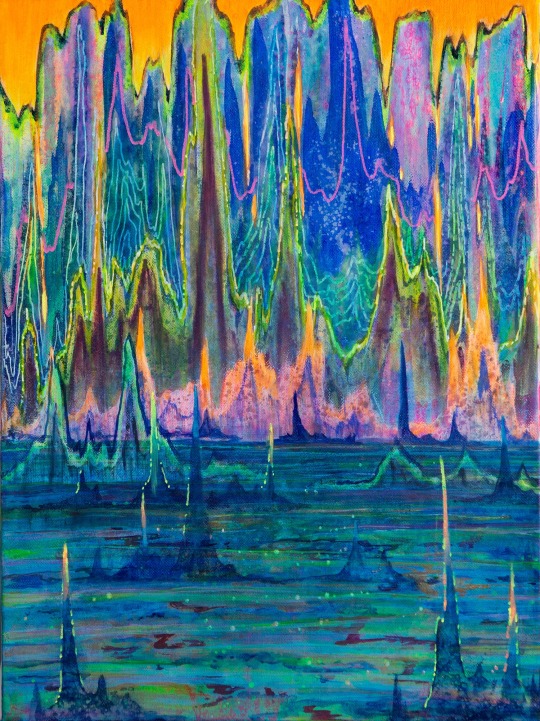

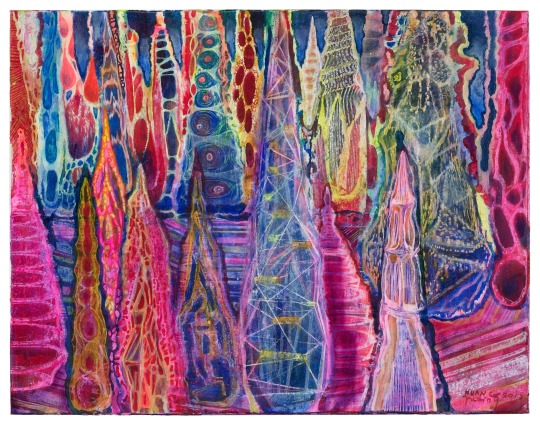

Huang Yuxing 🎨

Huang Yuxing - Mountain Bathed Under Golden Sun, 2018

Huang Yuxing - HABITAT - 2010

Huang Yuxing, Mountain with Chinese Zither, 2019

Huang Yuxing - Champion by- 2017

Huang Yuxing, Twilight, 2017

Huang Yuxing - Sunrise and Sunset, 2013

Huang Yuxing - The Trees Around the Small Plaza, 2018

Huang Yuxing - Sunrise - 2014

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

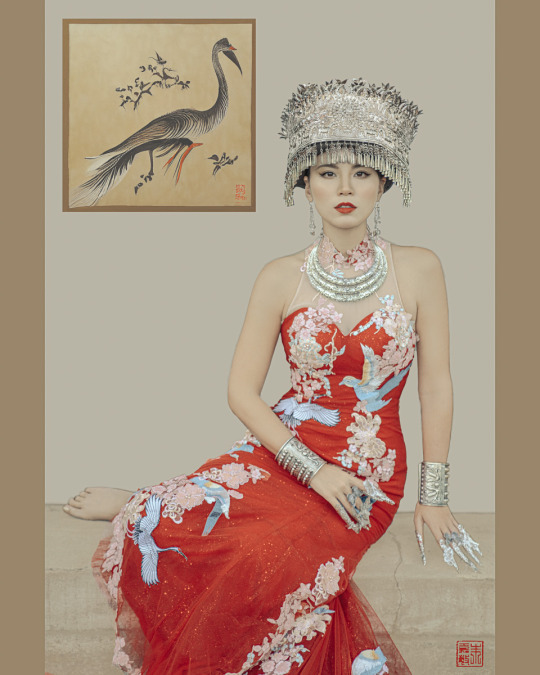

Trying out a new style, inspired by incredible @sunjun78 photography that renders like Chinese paintings.

I color-corrected in Photoshop, and penciled the outline using Wacom pen. It took a while, and I am still missing tons of details. This kind of meticulous style requires many hours of brush strokes. I have so much respect for Gongbi art craftsmanship.

The painting of the crane next to Nelly, is actually generated by Midjourney AI. I was going to extract the crane and use it as a background, but I like it so much that I render the AI art as is, instead. The AI even generated its own cryptic signature stamp. I have no idea what it says, but impressive.

The red stamp at the bottom right, is actually my name in old Chinese characters.

Coming soon - Before & after for this photo creation :)

Model: @nelly_hukuo

Crane Dress: @dreamdressesbypmn

Nymphalid Claws: @lorysunartistry

Plus other Miao tribal ethnic jewelry

Corner Painting: AI generated by #midjourney

Photography: @jajasgarden

#midjourney#chinesepainting#chinese painting#portraitphotography#seattlephotographer#gongbi#BeautifulBizarre#asianfashion#asianbeauty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

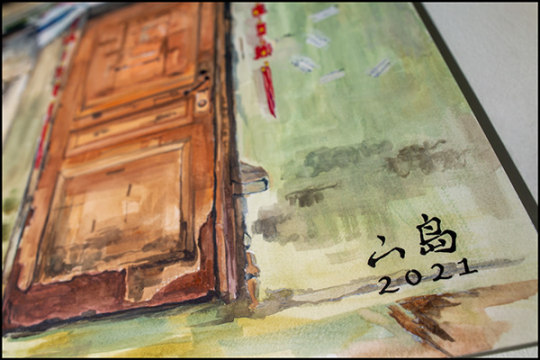

"Ping Ping An An" (平平安安)

“Architecture should speak of its time and place but yearn for timelessness.” – Frank Gehry

The Queen of the Orient, Paris of the East, The City of Shen (申城), our dear Shanghai goes by many eclectic names. No matter what you call it, the city on the sea attracts a certain type of energy that has the power to move you deeply. No matter where you come from, this is home. Here you’re safe and sound from whatever you were running from. Now it’s just living. And it’s easy in a scene where old meets new at every corner. Hungarian-Slovak architect László Hudec, commonly known as Shanghai’s master builder, designed over 60 buildings in the thirty years he lived here. His creativity resulted in many of the art deco architecture that still stands to this day. Hudec’s masterpiece was the tallest building in the metropolis, until the 1980s, the twenty-two story Park Hotel Shanghai on Nanjing Road. A walk down the bund might as well be a walk through time. Western-style buildings, Neoclassical to Beaux-Arts to Gothic to Baroque, sky high edifices, traditional Shikumen lane houses, It's all here. All you could ever ask for just a few blocks near Bao Ren Long (保仁弄). Although some say the street is already removed, the feelings evoked when walking past remain.

99.5*75.5cm. Unique

Art for sale: [email protected]

Follow our IG: island6_gallery

#Frank Gehry#architecture#contemporaryart#shanghai#island6#liudao#artcollective#artforsale#painting#gongbi#chineseart#shikumen#safe and sound

1 note

·

View note

Text

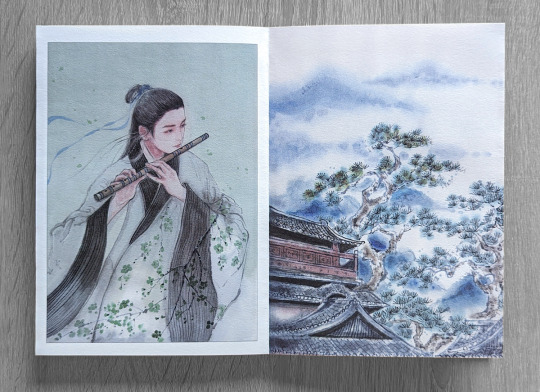

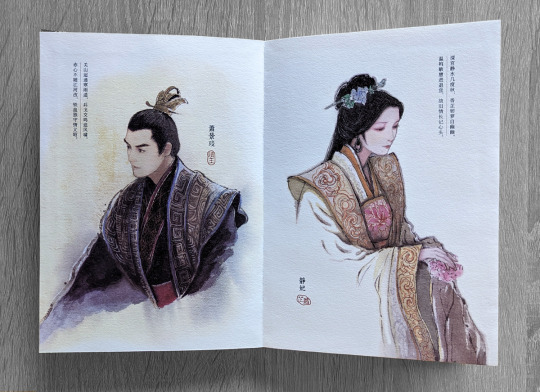

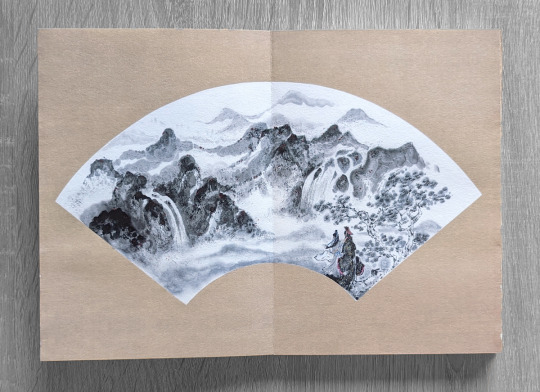

Fanbook Review: 《梅岭千秋》 by 壹染

《梅岭千秋》 (roughly Meiling Undying) is a 2016 fanbook with art by Yiran/壹染 and published by 溯年组, depicting scenes and characters from Nirvana in Fire. I had to get my hands on a copy after falling in love with the art.

Yiran paints with ink brushes and watercolor on xuan paper/宣纸, a famous traditional Chinese paper made from the qingtan/青檀 tree especially suitable for calligraphy and painting. Xuan paper is divided into raw/生宣 and processed/熟宣 types, the former more absorbent with a tendency for ink to run free, and the latter processed with alum to be more controllable for precision ink work (the two types of traditional painting, evocative xieyi/写意 and realistic gongbi/工笔, are often split along raw and processed xuan in their choice of medium).

Raw xuan is particularly unforgiving to beginners, but Yiran is a master of her craft, able to achieve both precise lines and textures as well as the misty landscapes so characteristic of Chinese watercolor on this paper (see her Lofter for her process and more art). She often paints an entire series of pieces on a traditional accordion booklet/经折装, a single long sheet of paper folded on itself many times, as she did for this project (photos from her Weibo, which also has more art):

The publisher took care to replicate the original booklet of pieces as closely as possible in the final product. Beneath the outer paper jacket is a cover made of woven Song brocade/宋锦, with 38 accordion-folded A5 pages inside. The pages are textured imitation xuan paper, printed with a lacquered black ink that glows under the light:

One side of the folded pages is mostly landscapes and scenes inspired by canon: Mei Changsu and Lin Chen in Jiangzuo beside flowers in bloom, an all-smiles Lin Shu embracing Jingyan in the before times. The other is a series of individual character portraits rendered with their attire from the show, their faces referencing the actors’s features but not overly imitative. There’s something revelatory in the way she paints a dreamy, ephemeral scene in one panel and then renders Jingyan’s robes with dramatic, almost impasto-like textures:

Each portrait is also paired with a poem written by 海月. Jingyan’s is

关山诏递寒雨遥,兵戈交鸣追风啸。

赤心不随江河改,铁血独守情义昭。

A possible translation:

Drifting bitter rain in mountains edict-sent,

weapons clash as galloping horses scream.

A pure heart enduring through shifting tides,

alone in his courage, loyalty brought to light at last.

I’ll end with my favorite piece, Chief Mei and His Majesty beholding their mountains and waters:

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zhang Daqian: A Visionary Master of Chinese Art

Zhang Daqian, also known as Chang Dai-chien, was a renowned Chinese artist who left an indelible mark on the world of painting and calligraphy. Born in 1899 in Neijiang, Sichuan province, China, Zhang Daqian is considered one of the most influential and versatile artists of the 20th century.

Zhang Daqian's artistic journey began at a young age when he studied traditional Chinese painting under his older brother. He later traveled extensively, exploring the scenic landscapes and cultural treasures of his homeland, which greatly influenced his artistic style. Zhang Daqian drew inspiration from classical Chinese masters, incorporating their techniques while also adding his own innovative approaches.

One of the defining characteristics of Zhang Daqian paintings artwork is his ability to master different styles and genres. He effortlessly shifted between ancient techniques such as meticulous gongbi and free-flowing ink wash painting. This versatility allowed him to express his creativity across a wide range of subjects, including landscapes, figures, flowers, and birds.

Zhang Daqian is perhaps best known for his landscape paintings. With his profound understanding of nature, he captured the essence of mountains, rivers, and other natural elements, infusing them with a sense of tranquility and spirituality. His landscapes often feature majestic mountains shrouded in mist, creating an ethereal atmosphere that invites viewers to immerse themselves in the beauty of the scene.

In addition to landscapes, Zhang Daqian also excelled in painting flowers and birds. He had a keen eye for detail, meticulously depicting the delicate petals of flowers and the graceful movements of birds. His brushwork displayed a remarkable sense of rhythm and energy, breathing life into his subjects and captivating viewers with their vibrancy.

Zhang Daqian's artistic genius extended beyond painting. He was also a skilled calligrapher, known for his bold and expressive brushwork. His calligraphy showcased his mastery of various scripts, from ancient seal script to flowing cursive script. Zhang Daqian's calligraphic works often combined poetry and painting, creating harmonious compositions that reflected his deep appreciation for the written word.

Throughout his career, Zhang Daqian artwork gained international recognition, and he became one of the most celebrated Chinese artists of his time. His paintings and calligraphy were exhibited worldwide, and his influence spread far beyond China's borders. He was not only a master of traditional techniques but also a visionary artist who pushed the boundaries of Chinese art, blending tradition with innovation.

Today, Zhang Daqian's paintings and artwork continue to be highly sought after by collectors and art enthusiasts alike. His ability to evoke emotion through his brushwork and his profound connection with nature remain timeless. Zhang Daqian's legacy as a pioneer of modern Chinese painting and calligraphy will forever inspire generations of artists to come, leaving an enduring imprint on the art world.

#auction news#artist#auction house#artwork#latest auction news#auctiondaily#art#auction#zhang daqian

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fic: this body yet survives, ch. 12

Relationship: Lán Zhàn | Lán Wàngjī/Wèi Yīng | Wèi Wúxiàn

Characters: Lán Zhàn | Lán Wàngjī, Lán Huàn | Lán Xīchén, Lán Qǐrén, Wèi Yīng | Wèi Wúxiàn, Jiāng Chéng | Jiāng Wǎnyín, Jiāng Yànlí, Su She | Su Minshan, Madam Jin, Jin Zixuan, Wen Qing, Jiāng Fēngmián, Niè Huáisāng

Tags: No War AU, Recovery, Trauma, Dissociation, Courtship, Courting Rituals, Near Death Experiences, Attempted Murder, Eventual Happy Ending, Panic Attacks, Vomiting, Siblings, Protective Siblings, Soup, Triggers, Protective Lan WangJi, Protective Lán Qǐrén, Yúnmèng Siblings Dynamics, Bad Parent Yú Zǐyuān, POV Third Person, POV Lan WangJi, reference to poisoning, reference to assassination, Reference to chronic illness, reference to infanticide, Depression

Summary: As winter approaches, a day goes awry.

Notes: See end.

Parts 1 & 2

Chapter 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11

AO3 link

-----------

The Nies only stayed one more night before returning to Qinghe, though Nie Huaisang insisted he would write several letters a week to Wei Ying, letting him know there was no pressure to write back, and followed through. The next several weeks were relatively busy, with Gusu and the Cloud Recesses preparing for the onset of winter, as autumn was a short season in the mountains.

Wei Ying received letters from both Nie Huaisang and Wen Ning in that time, and had managed to write back a few times, though once he just sent paintings. He sent a beautiful gongbi-style piece featuring Wen Ning standing tall and aiming his bow at a target, clearly a memory from the discussion conference at Nightless City. Shortly afterward, Wen-zongzhu wrote to ask about commissioning a large family portrait for display in the Fire Palace throne room, and insisting on paying ten times what Wei Ying asked. Lan Xichen happily provided a small studio where he could work, which was carefully locked with his invented talisman to prevent sabotage. Wangji took to quiet afternoons reading while Wei Ying painted, chaperoned by one of the Jiang siblings, xiongzhang, or shufu.

To Nie Huaisang, he sent freehand shui-mo paintings and sketches of birds he’d observed in the Cloud Recesses, often done while Wangji went on chaperoned walks with him in the back hills on a small, easily carried easel he gave as a courtship gift. Wei Ying received a praise-filled letter and a beautiful Qinghe-made tapestry of two snuggling rabbits in return, which was hung in the Jiang guest house across from his bed, for later installment in the jingshi.

Wangji commissioned a beautiful cloak for Wei Ying, a blue as pale as the Lan forehead ribbons, lined with fur, with embroidered mandarin ducks flying amid the clouds, a motif of the three gentlemen of winter below at the hem in a winterscape. He presented it as a courtship gift the first cold day, when Wei Ying’s breath misted under a nose red from the chill, and was pleased when his gift was immediately put to use.

Jiang Yanli cooed over the chosen embroidery, telling them she was certain they would have a happy marriage. Jiang Wanyin quietly told him Wei Ying was a little sensitive to cold due to his time lived on the streets, which was high praise on the timeliness of his gift and information that led him to commission a warm blanket as his next gift.

He loved the way Wei Ying blushed prettily upon receiving these gifts, the way he stuttered a little for several minutes, and knew this was what had led his zhiji, during the lectures, to tease him for the reaction. Part of him regretted not having given him the attention he deserved back then, but he could not turn back time, simply move forward appropriately.

Wei Ying’s courtship gifts to Wangji included beautiful paintings, to his delight, and literature and poetry he ordered special from the bookstore in Caiyi. The choices displayed his impeccable taste and often included books of romantic poetry. One gift he particularly loved was a tiny duo of wooden rabbits, carved by Wei Ying in spectacular detail, which he kept on his desk in the jingshi, where he could enjoy it while he worked.

Wei Ying’s siblings, with the help of Nie Huaisang’s urging via letters, convinced him that staying with them until the wedding was the best course of action, and then he would be safe in the jingshi with Wangji.

It was a good thing they had.

When they went to retrieve the rest of his belongings from his old quarters one afternoon, the doors sealed behind them, locked with Wei Ying’s talisman used as a tool of imprisonment, and the sound of snarling dogs filled the room.

Wei Ying climbed into the rafters immediately, managing to leave grooves with his fingernails in the woodwork in his haste, his pupils blown in terror. Though they eventually found and disabled the talisman responsible for the sound under the bed, it took another ke to coax him down. He was almost catatonic, and Wangji started to consider using Bichen to fly up and carry him down.

Finally, he seemed to come back to himself, his eyes clearing as they landed on Wangji. His only warning was “catch me?” murmured so softly he nearly missed it. Then Wei Ying let himself fall from the rafters, arms open, trusting him, and he did as bidden, pulling him close and cradling him when he landed safely in his arms.

“You caught me,” Wei Ying whispered tremulously.

“Mm. I will always catch Wei Ying,” he assured him, keeping his touch gentle as he helped him sit, though inside he was raging at the person who would do something so vile.

Wei Ying trembled terribly and didn’t seem able to stop, clearly needing time to recover from the scare, so they wrapped him first in his warm winter cloak, which he had hung over a privacy screen upon entering his former quarters, and then in the blanket from the bed—for comfort rather than cold. He was wan, his skin clammy, a sheen of sweat on his upper lip, and when Wangji checked his pulse it seemed a bit irregular, so it was better he rest until they could get him to a healer. Jiang Yanli sat with him at the table and straightened his headband, which had gone askew on his forehead in the tumult, tutting over him.

Meanwhile Wangji and Jiang Wanyin tried to troubleshoot a way out. Or, rather, one that didn’t involve brute force and trigger the backlash. Wangji knew there had to be a way, but Wei Ying was still shaking, his eyes distant.

Just as they were debating who would trigger the backlash and be gifted blue hair—each specifically arguing to be the one—Wei Ying spoke.

“I didn’t make it for this,” he murmured, sounding both dazed and affronted at the way his locking talisman had been misused. “It has a failsafe, though—Lan Xichen and Lan-xiansheng know it.”

Wei Ying pulled a piece of talisman paper from his sleeve, and Wangji quickly brought over an inkstone and brush from his desk before he could use blood to write it. Wei Ying’s fingernails were cracked and bleeding, imbedded with splinters of wood, and Jiang Yanli made a noise of distress upon seeing them. Wangji forced himself to quash the desire to tend to them immediately, telling himself Wei Ying would benefit more from a healer and not being trapped. He could sense Jiang Wanyin tensing beside him when he noticed, possibly warring with the same urge.

He took the talisman when it was complete, not wanting Wei Ying to use his spiritual energy before a healer cleared him. The handwriting was shaky enough for concern.

The door unsealed when he applied the talisman, and Wei Ying told them to keep the disabled locking talisman so it could be examined.

Wangji wished they hadn’t destroyed the talisman responsible for the barking so it could be examined as well, but at the time they had been more concerned with Wei Ying’s terror.

“The locking talisman should be keyed to the culprit’s qi,” Wei Ying murmured to him as he moved to help him stand. “I’ll have to figure out how to trace it.”

“You don���t have to figure out anything,” Jiang Wanyin told him roughly. “Let others take responsibility.”

Wei Ying wasn’t able to stay steady on his feet, and it was decided Wangji would carry him to the infirmary, escorted by Jiang Yanli, while Jiang Wanyin sealed his quarters and took the disabled locking talisman to xiongzhang and shufu. Moving the rest of his possessions to the Jiangs’ quarters would have to wait until the healers cleared him, and until his quarters had been searched more thoroughly. Jiang Yanli carried Wei Ying’s sword, which he had dropped in his scramble to the rafters.

The healer on duty immediately brought them back to the same room Wei Ying had spent the night in after the lotus incident, and Wangji knew they had likely called for bedding again, with the knowledge the Jiang siblings would never leave him to be alone; he hoped they had accounted for his similar intent. She lit incense, the scent of sandalwood filling the air, before examining Wei Ying, who was still shaking intermittently, tiny tremors, almost like muscle spasms.

“You’ve had a panic attack, Wei-gongzi, but it has not disrupted your qi or core,” she said when she had finished, looking at them for further explanation.

Jiang Yanli explained quickly, and the healer’s jaw clenched, showing her anger at the continued targeting of Wei Ying, something he appreciated wholeheartedly. He tightened his grip on Bichen, letting the way the decorative metal patterns bit into the skin, imagining the what punishments could be meted out against the person who had, again, targeted Wei Ying.

“They couldn’t have gotten in once we locked it up,” Wei Ying murmured once Jiang Yanli trailed off, “so it’s been there, waiting for me to come back and trigger it, since the initial sabotage.”

Wangji blinked at him; even just having had a panic attack and still recovering from the aftermath, Wei Ying’s genius shined, and he had already made a significant observation, the logical progression of thought flying through him. His beloved’s mind was a wonder.

“It’s a good thing you’re not going back there, then,” Jiang Yanli said decisively. “A-Cheng and I will retrieve your belongings and make sure there aren’t any other surprises.”

It was a testament to how shaken he was that Wei Ying made no effort to argue, only nodding in agreement. His uncharacteristic pliability reminded Wangji of the Wei Ying of not too long ago, subdued in a way Wei Ying should never be, unreachable. The understanding that Wei Ying’s condition could worsen again terrified Wangji.

The healer left the room and returned with a tray of medicine, servants trailing after her with piles of bedding—three, Wangji was happy to see—and several chairs, as it was hours yet before hai shi. This also made it clear she wanted to keep him for observation.

She closed the door when the servants left, then offered him a bowl of medicine.

“Wei-gongzi, this is a slight sedative, which will relax your muscles and ease some of the effects of the panic attack. It may make you a bit sleepy, but the aftermath of the shock will likely do the same anyway,” the healer said, giving him a choice rather than insisting he take it.

Wangji didn’t know whether she was giving him the option to refuse it because his condition was less severe, or if the choice was meant to let Wei Ying feel in control following a violation of his sense of safety. Either way, he appreciated her not removing his agency.

Wei Ying didn’t hesitate to take the bowl, which indicated just how poorly he felt. Wangji had to force himself to take measured breaths, seething at how little he could do to help in this moment.

When he was finished, the healer set the bowl aside and turned her attention to his hands, spreading a topical numbing agent over the tips of his fingers before carefully pulling bits of wood from under his nails and the pads of his fingers. Once she was satisfied all the splinters had been removed, she spread a salve on them and bandaged them.

“They’ll be healed by tomorrow,” Wei Ying protested as she finished bandaging the first finger.

“That may be, but until then, bandages,” she said sternly.

“It’s important we properly care for your injuries, A-Xian,” Jiang Yanli added, sitting beside him on the bed and placing a comforting hand on his shoulder.

Wei Ying put up no further resistance, and as the healer was halfway through his second hand, a soft knock at the door announced the arrival of Jiang Wanyin, who had both xiongzhang and shufu in tow.

Xichen blanched a bit as he walked in, his eyes alighting on the healer bandaging Wei Ying’s mangled fingers, and he and shufu bowed to them once the door was closed.

“Wei-gongzi, we truly apologize,” Lan Qiren stated, sounding ashamed.

“Ah, don’t bow, please! It’s not your fault,” Wei Ying said, sounding a little frantic and waving the hand that wasn’t in possession of the healer.

“You were targeted again on our watch,” xiongzhang said, his voice tight with frustration.

“It isn’t a new attack, just a trap left behind the first time. They couldn’t have gotten in again with the locking talisman engaged,” Wei Ying insisted. “And anyway I wasn’t alone.”

Some of the tension seemed to leave Xichen at that, but shufu shook his head.

“We were tasked with searching your room to discover if anything further had been sabotaged,” Lan Qiren argued. “We were derelict in our duty to you.”

“Something triggered it. If you didn’t trigger it, I’m not surprised you didn’t find it,” Wei Ying said.

Wangji could see Wei Ying’s fatigue, and so when the healer vacated the seat beside him after finishing the bandaging, he slid in to take it, as well as Wei Ying’s hand, hoping the gesture would comfort him. If he could not fight the person causing Wei Ying pain, he could at least do this.

“I don’t want to assign blame,” Wei Ying said after a moment, squeezing Wangji’s hand slightly. “It’s the fault of the asshole who set it up, no one else.”

He glanced at his siblings as he said the last bit, and Wangji knew he was reiterating what he had said to them on multiple occasions, particularly after it became clear that both of the Jiang siblings were wracked with guilt over having not done something before the incident to stop Madam Yu, as though they weren’t also abused, as though they hadn’t been children without sufficient power.

“I think we’re all more interested in finding the culprit,” Jiang Yanli cut in softly. “We don’t apologize for things that aren’t our fault.”

Shufu inclined his head and nodded in acknowledgment, but Wangji knew his uncle’s sense of guilt would remain—he, too, blamed himself for not somehow knowing of Wei Ying’s abuse.

“The talisman master is searching in the library for a way to identify the qi signature,” xiongzhang said. “It may well not exist yet, but he’s hoping to find ideas in existing material.”

“I can help him,” Wei Ying offered immediately.

Lan Qiren shook his head.

“You must rest, Wei Wuxian. Your recovery is what you should focus on.”

His tone brooked no argument, and Wangji knew he was referring to more than just tonight—Wei Ying was still recovering from his near death, at least psychologically. Wangji knew the healers kept an eye on his scars, which had threatened muscles needed for sword forms. He was still monitored when he trained or sparred. The damage would have been worse if not for Wen Qing’s treatment and the use of Gusu Lan songs of healing. A lesser cultivator would have died from just the whipping, to say nothing of the drowning.

Wei Ying only nodded, and his expression was heart-wrenching, as he tried and failed to hide the sheer frustration with his own health.

“Do not push yourself, Wei-gongzi,” xiongzhang said softly. “Your health is important.”

Wangji squeezed his hand to indicate his agreement with that sentiment, and was pleased when Wei Ying glanced at him and managed a wan smile—one that was meant to be reassuring, as tremulous as it was.

“Wei Ying looks tired,” he murmured. “I will not leave.”

Wei Ying simply nodded in reply, curling closer to him, his head on the edge of his pillow and forehead against Wangji’s arm, a request for closeness he could not deny.

Pointedly not looking at the multiple chaperones in the room, he sat on the bed and helped Wei Ying shift until he was curled against him, his head resting against his shoulder. It was decidedly less than proper, but his beloved needed the closeness.

No one commented, hopefully realizing Wei Ying’s comfort was more important in this instance, particularly since he was already nodding off. Rather, Jiang Yanli wrapped a blanket around them both.

“We can have dinner sent here from the kitchen,” xiongzhang offered.

“I have soup cooking,” Jiang Yanli said, shaking her head. “And other parts of the meal are in progress. I just paused to help clear out A-Xian’s room with him.”

Shufu stroked his beard, then sighed and cut through to the easiest solution.

“I can stay here to chaperone, so Jiang Yanli and Jiang Wanyin can finish preparing dinner to bring here. Xichen, it may be best if you retrieve Wangji’s qin and anything else he will need for the night. If the Jiangs need help bringing dinner and other sundries, you should assist them as well.”

Jiang Wanyin headed for the door immediately, likely wanting to work quickly so they could return to Wei Ying’s side sooner. Jiang Yanli hesitated, leaning close to Wei Ying, peering around the blanket to check on him and smiling when she found he was asleep before following her brother out. Xiongzhang asked him what items he wanted from the jingshi—whose lock talisman would recognize him, thankfully.

Wangji was able to give a brief list, as circumstances would change his nightly routine—general hygiene items, his comb and hair oil, a sleeping robe, and fresh robes for the morning. Aside from his guqin, he needed little else.

Though he was still holding Wei Ying in a manner that was inappropriate for courtship, shufu made no move to separate them, instead settling in a chair and pulling his xiao from his sleeve.

“We will consult an augur on suitable dates, once this is resolved,” he said.

This left Wangji reeling; courtships often lasted a year or two, and the implication of consulting now meant a shorter troth, perhaps could imply Wei Ying as undeserving of proper courtship.

“The setting of an auspicious date a year into the future is not unheard of, and will solidify Wei Wuxian’s position to the world,” shufu explained. “It cannot help us with finding the traitor in our midst, but will further protect his reputation.”

Particularly if word got out that Wei Ying had been targeted from within the sect, it would stir rumors and gossip about how protected or welcome he was, Wangji knew. But announcing an auspicious date and dealing with the saboteur firmly for their crimes would counter those strongly.

Politics was not something Wangji understood or would ever want to deal with, and he was thankful that shufu was managing that aspect in the protection of Wei Ying.

Wei Ying, who slept trusting in their protection in his arms now, his face slack and peaceful despite the terror he’d felt half a shichen ago and the painful-looking torn nails.

Wangji did not trust himself not to tear the culprit limb from limb for hurting Wei Ying, and so it was good shufu would handle that as well.

“Regardless of the current situation, it is beyond time to set a date, with the way both of you have been unknowingly courting since you were fifteen,” shufu said, his voice wry.

Wangji felt his ears heat, to know shufu knew of his regard for Wei Ying so far back. Lan Qiren smiled at him as though pointing at how he was currently holding Wei Ying, and he supposed he wasn’t subtle, even now drawn to his zhiji.

“If someone had told me back then I would happily welcome him as your husband, I would have thought them mad,” shufu continued, his voice betraying his sense of guilt. “Cangse Sanren would be pleased with the change, I think, but not what it took for it to happen.”

He was relieved his uncle, essentially the only remaining parental figure in his life, had come to approve of Wei Ying, but also wished it had not taken his near-death. Wangji wished it had never happened, that Wei Ying could be unburdened by the trauma of it.

“Wei Ying hides his hurts,” he said, though he knew Lan Qiren’s sense of guilt was unlikely to be swayed.

After all, it didn’t help his own sense of guilt, even knowing he could not have been aware of the pain Wei Ying’s smile hid.

“I was biased toward him because I was not fond of his mother,” Lan Qiren said. “My judgment of him was a flaw in myself.”

Shufu brought his xiao to his lips and started playing a song of healing, one meant to boost qi to heal injuries faster, and one that had been played many times during Wei Ying’s convalescence when he had first arrived in Gusu so grievously injured.

Strictly speaking, it was unnecessary given that his injuries were not nearly severe enough to warrant musical cultivation. But Wangji knew shufu’s actions were an attempt to ensure Wei Ying’s pain was as brief as possible, were his way of doing something in the face of helplessness and impotence.

Then he shifted into Clarity, and Wangji felt the rage-induced tension in himself, the way it seethed in an uncomfortable way under his skin, and he let in the music to help clear his heart and mind of it. This was shufu’s way of acknowledging and empathizing with his anger, while also encouraging him to have a level head. He couldn’t protect Wei Ying effectively with rage clouding his judgment.

They could only wait now—for the Jiangs to return with dinner and xiongzhang with Wangji’s belongings, for the talisman master to find a way to trace qi, for the ability to root out the saboteur and make Wei Ying safe.

Wangji hated waiting, but at least he was permitted to do so with Wei Ying in his arms, breathing softly and safe against him, as safe as possible in this moment.

-------------

Gongbi is a style of painting that is meticulous and detailed, and likely would have taken hours. You can imagine he started painting it after Wen Qing’s visit, meaning to send it as a sort of apology. Shui-mo is literally water and ink and refers to an ink painting with watercolor. These are the two main techniques in traditional Chinese painting.

On a personal note, my luck finally ran out after over 2 years of careful masking and hygiene, and I caught Covid. Worse, my mom came to visit me for my 39th birthday and one of her gifts was Covid. At first I thought it was hayfever, but it kept getting worse. Home test confirmed we were both infected. I hadn’t had my second booster yet, and the new variants are supposedly dodging the antibodies somehow.

Fortunately, it stayed an upper respiratory infection and I was able to keep it from going into my lungs—something I was worried about because I have chronic bronchitis. (One of my risk factors.) But it was miserable. The last time I got that sick was after my dad’s sudden death when my immune system crashed and I got (shocker) bronchitis. But seriously, feeling like you’re swallowing broken glass sucks.

It’s been 3 weeks and I’m still exhausted, but it’s hard to know if that’s residual from the covid or if the covid triggered my autoimmune disease to act up more than usual. Since a friend from high school has diagnosed long Covid, I’m keeping track to see if I need to go to the doctor over it.

And don’t get me started about waking up to find I have less bodily autonomy than a corpse.

#the untamed#untamed fanfiction#untamed fanfic#untamed fic#wei ying#wei wuxian#lan wangji#lan zhan#wangxian#jiang yanli#jiang wanyin#jiang cheng#lan xichen#lan qiren#cql#chen qing ling#cql fanfic#cql fanfiction#cql fic#mo dao zu shi#mdzs#mdzs fanfic#mdzs fanfiction#mdzs fic#my fanfiction

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/30/22)

Qiu Ying (Chinese, c. 1494-1552)

Spring Morning in the Han Palace (c. 1530-50)

Section of a handscroll. Ink and colors on silk, 99 cm. high

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Qiu Ying was a Chinese painter who specialized in the gongbi brush technique. He was born to a peasant family in Taicang (now Jiangsu Province) and studied painting under Zhou Chen in Suzhou. Though Suzhou's Wu School encouraged painting in ink washes, Qiu Ying also painted in the green-and-blue style. He painted with the support of wealthy patrons, creating images of flowers, gardens, religious subjects, and landscapes in the fashions of the Ming Dynasty. He incorporated different techniques into his paintings, and acquired a few wealthy patrons. His talent and versatility allowed him to become regarded as one of the Four Masters of the Ming Dynasty.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

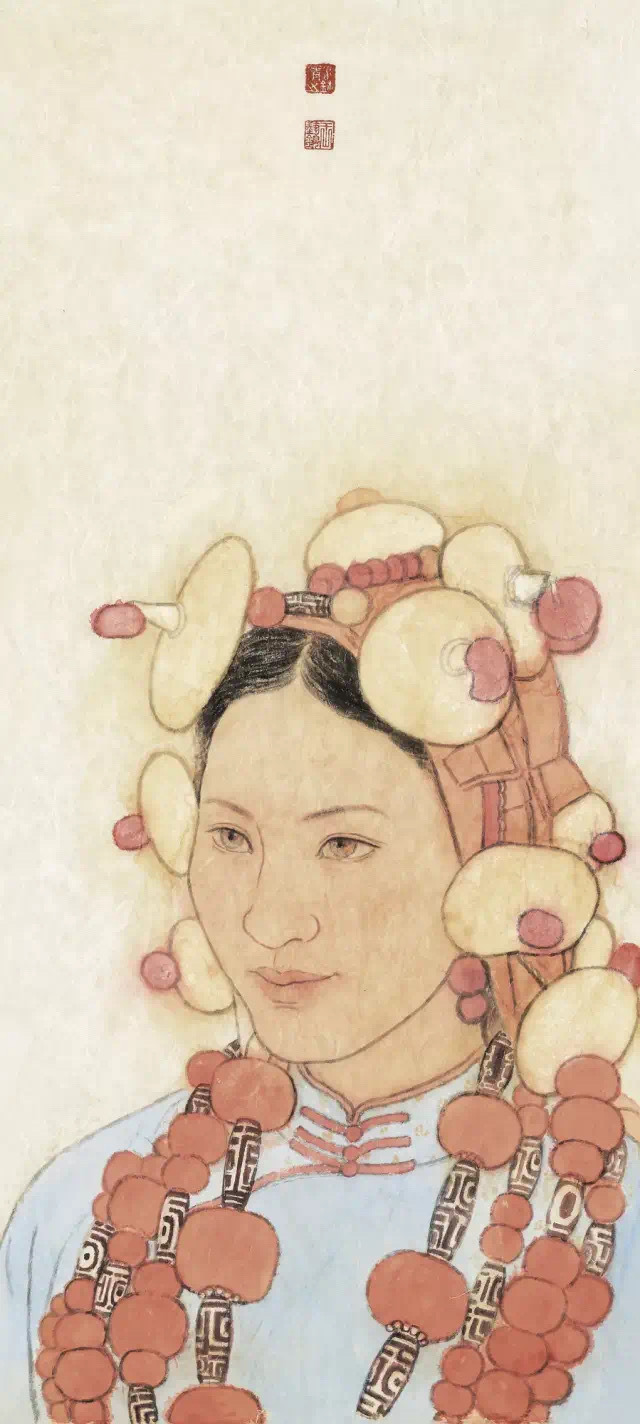

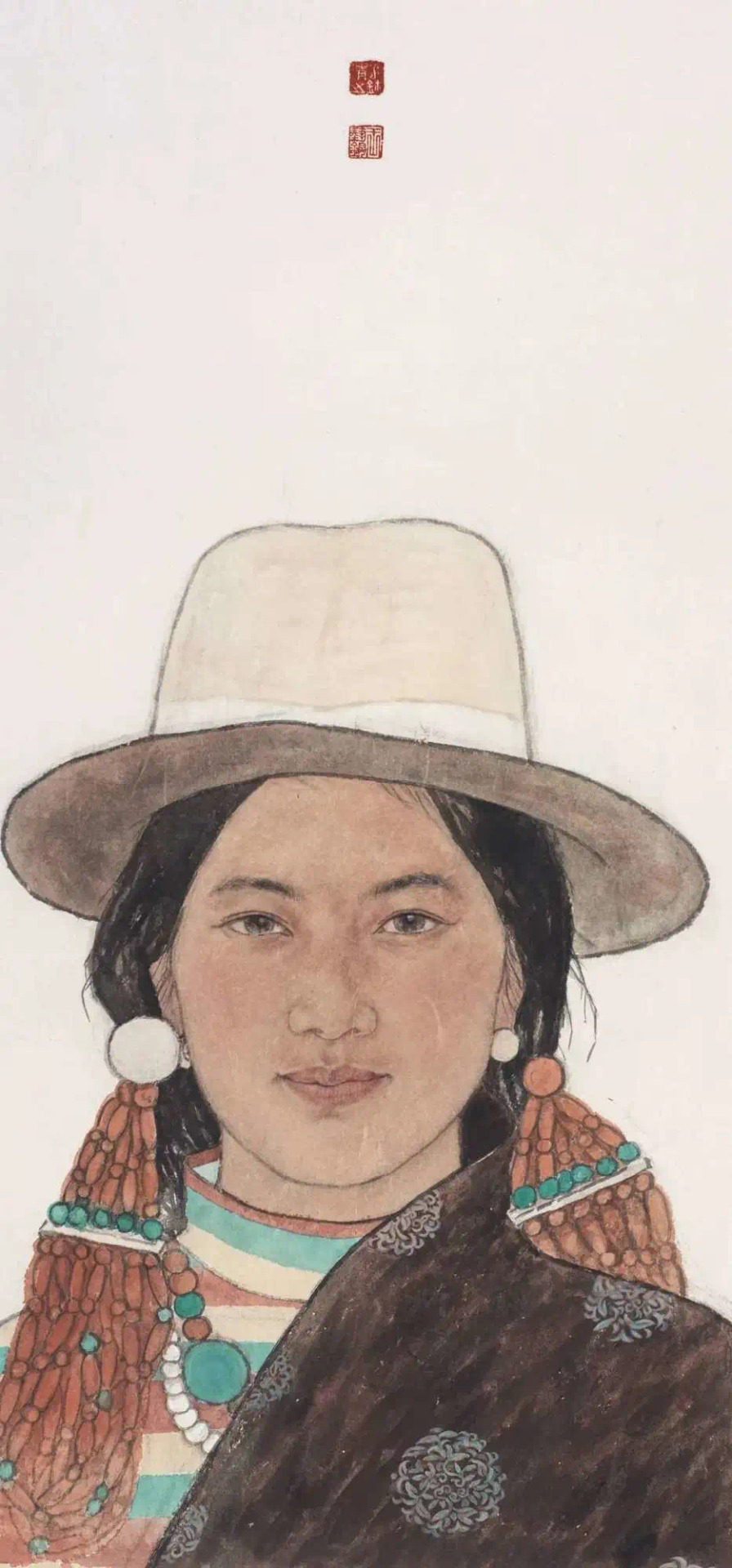

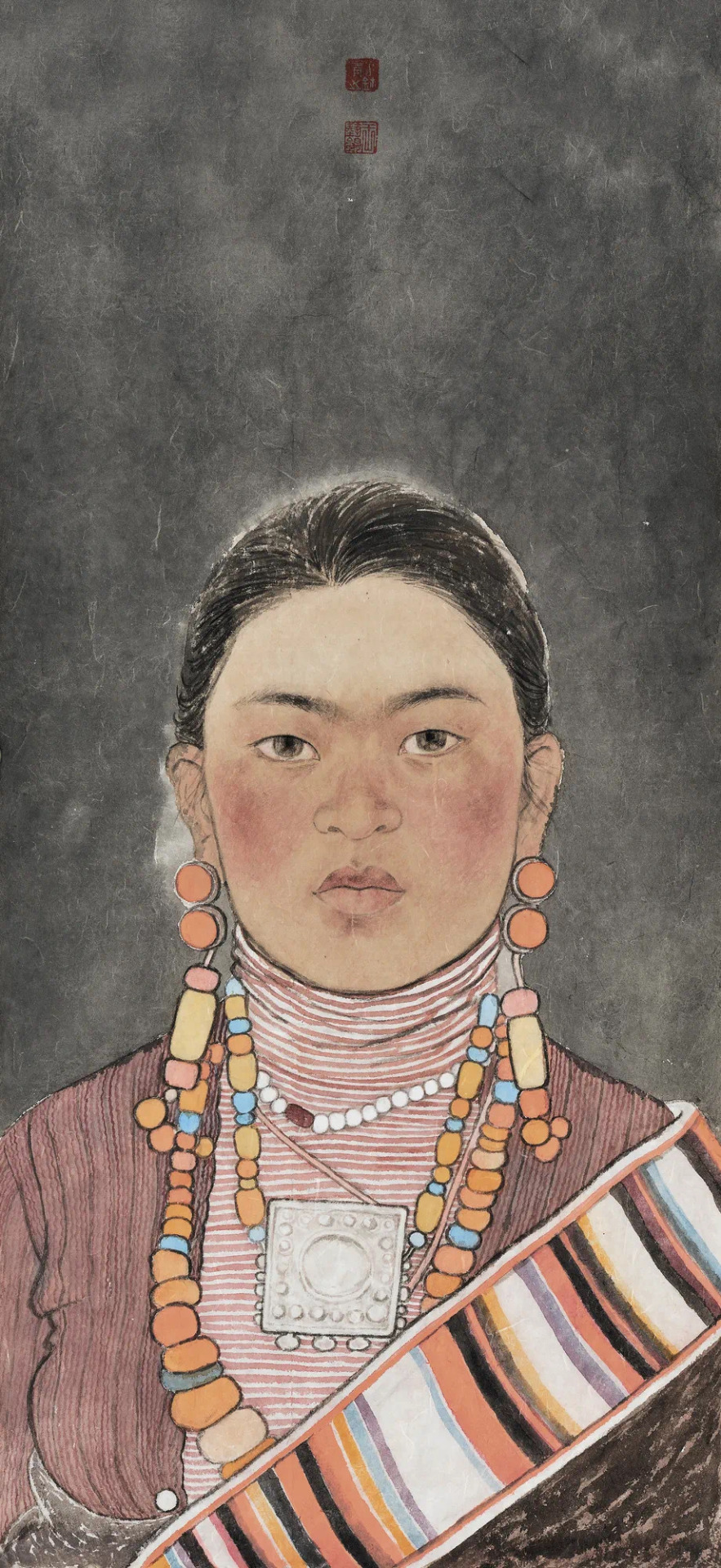

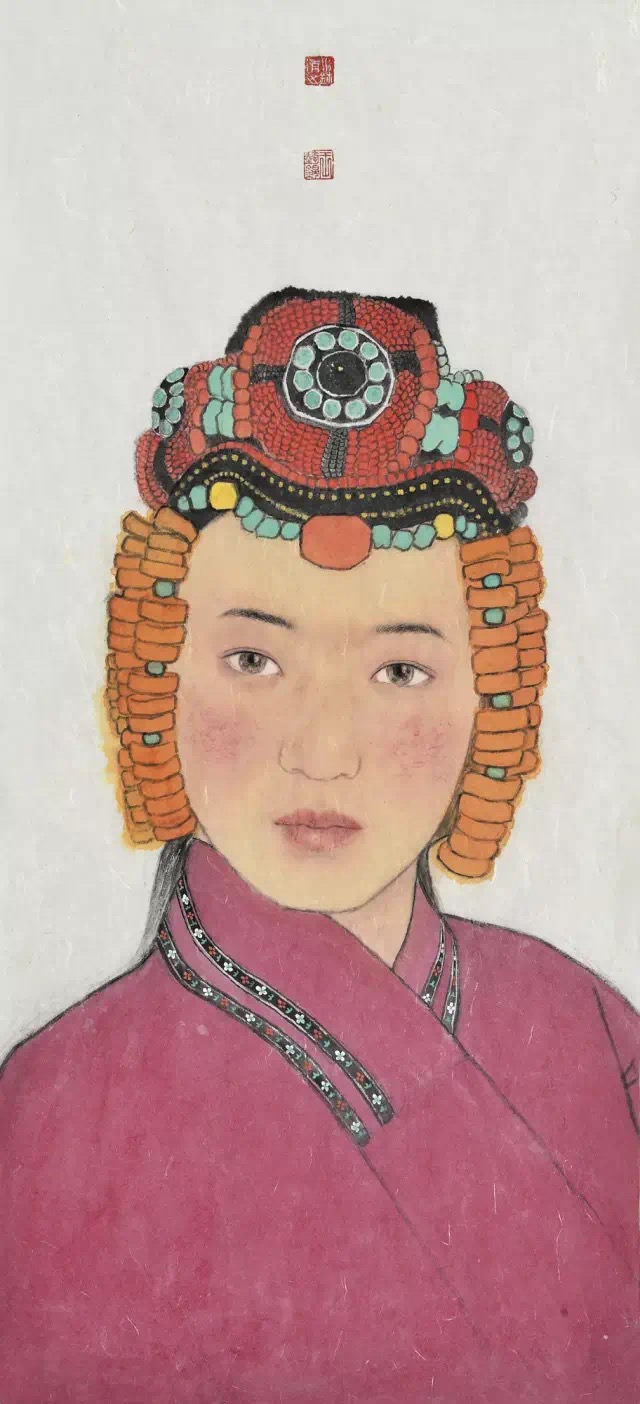

chinese artist 王水清wang shuiqing(renmin university of china school of arts)

#china#art#paintings#illustrations#gongbi#ethnic portraits#tibetan#guohua#chinese painting#female artist

824 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Research: Cheriue Ka-wai Cheuk

https://theartling.com/en/artzine/10-contemporary-ink-artists-reshaping-medium/

0 notes

Text

In the wake of the new century’s economic boom Denis frequently visited China as a qualified interpreter, a journalist and a commercial representative. He was lucky to have met several native painting masters and was eventually granted a chance to study Eastern painting tradition first hand. Almost three years of heavy practice, which included mastering gongbi and xieyi techniques, helped Denis determine his true vocation and inspired him to take on the path of a professional artist. Before leaving China Forkas developed the principles of his Eglantine Breath philosophy. The approach – aimed at balancing the Apollonian and the Dionysian impulses and reviving the ancient spirit of harmony in a work of art – merged ceremonial magic, meditation and technical prowess in a single current.

- Season of Mist

#denis forkas#study for triton’s mirror#fever dream of a knight being devoured by his armor#baldrs draumar. eljuðnir#dream of a parasitic grove#study for andromeda II

0 notes

Text

Introduction to Chinese One Stroke Painting

Chinese Brush Painting is meant to be more than portraying an object. It acts as a channel of symbolic expression. The art of Chinese Brush Painting differs in both styles as well as execution. The most astonishing weird fact about this art form is that each brushstroke defines a move that generates a specific portion, due to which the painting is neither enhanced nor it can be rectified upon once drawn. While painting, an artist doesn't require any sketch or any role model. The artist can mentally construct a painting through random strokes by transporting his imagination on a mulberry paper. This technique is standardly emphasized more in Chinese paintings. Originating in 4000 B.C., traditional Chinese Brush Painting has made a remarkable development over the recent period of more than six thousand years ago. The growth has inevitably reflected on the changes of time social conditions. Chinese Painting focuses on both skills of painting as well as fostering nurturing one's character soul. Humans, landscapes, flowers birds are some of the important subjects that are highlighted in this traditional art form. Ancient paintings include painting on silk, which is well known for its original style distinctive features. Over the centuries, the practice of art among artists made it an art, which was further subdivided into a multitude of schools. This Chinese painting has a rich history as an enduring art form that is popular around the world. The essence of Chinese painting paves the way into the artistic, aesthetics, cultural background religions of ancient China. The painters normally painted on silk or rice paper ascended to make a rigorous painting. The ancient painting masters created a wealth of masterpieces. These masterpieces depicted varied painting skills aesthetic thoughts. These thought skills uncovered ancient knowledge on philosophy, politics, religion, culture, literature, art, society nature. Brush, ink, ink stick, traditional Chinese painting pigment, treated Xuan paper, silk seal were some of the commonly used materials in Chinese One Stroke Painting during the ancient period. Chinese Brush Painting techniques Gradually, Chinese artists started adopting Western techniques which included 2 styles: Freestyle which is more whimsical, colorful deceptively simple. Meticulous (Gongbi) which is realistic based on a limited palette. The modern Chinese artists decided to combine the 2 styles. They made the ink by grinding ink cake into the inkstone with little water. The amount of water differs depending upon the consistency of the ink. Thick ink appears to be glossy deep whereas, thin ink appeared to be livelier.

Penkraft conducts classes, course, online courses, live courses, workshops, teachers' training & online teachers' training in Handwriting Improvement, Calligraphy, Abacus Maths, Vedic Maths, Phonics and various Craft & Artforms - Madhubani, Mandala, Warli, Gond, Lippan Art, Kalighat, Kalamkari, Pichwai, Cheriyal, Kerala Mural, Pattachitra, Tanjore Painting, One Stroke Painting, Decoupage, Image Transfer, Resin Art, Fluid Art, Alcohol Ink Art, Pop Art, Knife Painting, Scandinavian Art, Water Colors, Coffee Painting, Pencil Shading, Resin Art Advanced etc. at pan-India locations. With our mission to inspire, educate, empower & uplift people through our endeavours, we have trained & operationally supported (and continue to support) 1500+ home-makers to become Penkraft Certified Teachers? in various disciplines.

0 notes

Text

Chinese art: considered the oldest traditions in the world,

Chinese painting: guohua which means native painting, use of a brush dipped in colored ink, similar to the technique of calligraphy. their canvas is mostly silk or paper. They are usually displayed using hanging scrolls or hand scrolls where a hanging scroll is displayed vertically on a wall while hand scroll is displayed horizontally on a sectioned table.

2 techniques, Gongbi and Shui-Mo

Gongbi: also called as meticulous, this brush technique is used to paint highly detailed designs using precise brushstrokes

Shui-Mo: also known as inkwash, it creates different shades by varying the density of the ink, practiced by the literari which means the highly educated men in ancient china society so its also called literari painting

Calligraphy: the art of decorativepainting, is considered to be the most sophisticated form of visual art in China.

Sculpture:

Terracotta: also known as baked earth, it is a clay earthenware ceramic that can be easily molded into all sorts of shapes and figures

Terracotta army: represents the army of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of china and was buried together with the emperor with over 8,000 soldiers and it was crafted according to the rank and position in the army.

Pottery: refers to the objects made from clay and hardened by varying degrees of heat. early pottery in china had crude cord marks and designed using geometric shapes, later advancements included rhythmic brush strokes and were often used for burial and religious rituals

Porcelain: fine delicate texture, soft hue, and a clean refined sculpture, earliest porcelain was discovered in the shang dynasty between 17th to 11th BC and is made into all forms of items

Architecture: the features of chinese architecture gives emphasis to articulation and symmetry or in short, they have to be symmetrical and should also contain a sense of balance and harmony.

0 notes