#medieval military history

Text

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: Sieges Are Awesome

so I just watched ANOTHER TV show where the characters could have simply barricaded themselves inside a VERY cosy and defensible fortress instead of heading outside to get killed/maimed/captured by the baddies

I call this Television Abhors a Siege and it is EVERYWHERE and I hate it

I HATE IT

yes, I know the writers look at each other and say, well, if our characters retreat to their stronghold then how will we fulfill our Swords Go Clang quotient for this episode?

this is only because the writers lack both imagination and education

you see, I've been reading medieval military history in exhaustive detail now for 8 years and SIEGES ARE AWESOME, both tactically and dramatically!

tactically, sieges make sense, because there is no way to thwart an enemy and buy time like HIDING SAFELY BEHIND A STONE WALL. the only time you would not do this is when a) you have a realistic chance of pulling off a surprise attack (the TV characters are never smart enough to do this) AND b) there is no realistic hope of circumstances altering to favour you in the near future (the TV characters never consider this either).

also historically speaking, whenever people looked at each other and said "this siege has no realistic hope of success" they did not march out to throw themselves on the enemy's swords: they negotiated and usually with great success (the TV characters never consider this either).

but let's say you're in one of the VAST MAJORITY of situations where a siege DOES make sense and only the most unhinged mental gymnastics would justify leaving your fortifications to fight (see: the majority of TV shows and movies that deal with this scenario)? does this mean that your characters must sit inside their walls twiddling their thumbs?

pfft don't be silly

sieges are totally dramatic!

it's not about LEAVING your fortifications to fight, it's about USING your fortifications to fight.

your baddies could try everything to get in and there might be fighting over a gate, a breach, or a tunnel/mine?

your characters might sally out under cover of night to destroy the enemy or their weapons?

one of your characters might escape the fortress in a desperate journey to find help?

your characters might turn out to have a traitor or saboteur in the group?

there might be injured people who need urgent attention, or supply shortages?

a FRICKING METEOR might fall out of the sky onto the heads of your enemies, sending them running and allowing you the opportunity to regain the initiative? (and if you think this couldn't possibly have happened, something very close to this literally happened at Antioch in 1098 during the First Crusade)

anyway this is just to say that I am begging you all to reconsider the dramatic potential of the noble siege. for one thing, it makes the characters look like total imbeciles if you ignore it. and for another, sieges are AWESOME.

eta: I learned all this doing the study for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my historical fantasy epic of the medieval crusader states! Book 4, A CONSPIRACY OF PROPHETS, puts my own magical spin on the 1098 siege of Antioch ;)

#writing#writing tip#writers of tumblr#writing fight scenes#military tactics#writing battles#medieval#medieval history#middle ages#historical fiction#history

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

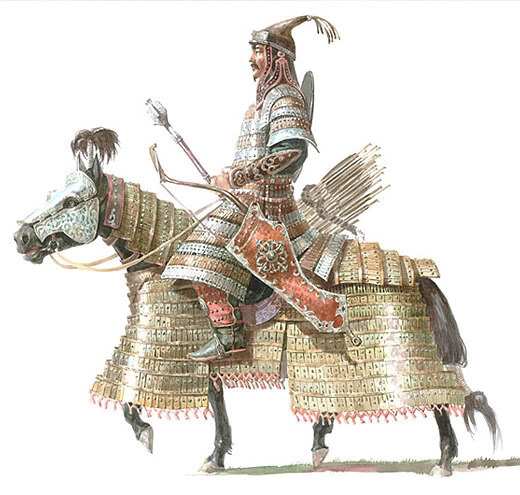

The Forgotten Mongol Heavy Cavalry,

When it comes to legends of the vicious Mongol conquests horse archers seem to be the celebrity rock stars of the Mongol Army who get all the fame and admiration. Depictions of Mongol battles in modern times usually show wild barbarian Mongol horse archers riding circles around enemy formations while showering them with volley after volley of arrows. Missing are the less glorified Mongol heavy cavalry, an absence which I’m sure would make the Great Khan sad because the Mongols had fine heavy cavalry. Not to put down horse archers, but horse archers alone don’t always win battles. While horse archers have their advantages, they also have several weakness and limitations, especially against opposing heavy infantry and cavalry equipped with shields and armor while in a defensive battle formation. What made the Mongols effective was not the mere fact they had horse archers, but because they had better tactics, among them combined arms tactics where they were able to coordinate the abilities of different units to accomplish a goal on the battlefield. This isn’t just a principle of Mongol warfare, but a principle of warfare in general. Whether we're talking ancient times or modern warfare, the side that has better combined arms tactics typically wins.

The early Mongol Army consisted of 60% horse archers and 40% heavy cavalry. Later the Mongols would adopt new units such as heavy infantry, light infantry, siege units, and artillery conscripted from the peoples they conquered. However for this post I’m only referring to the early Mongol Army commanded by Genghis Khan and his general Subutai. The purpose of the horse archers were as skirmishing units; to harass, sow chaos and confusion, and weaken the discipline of enemy ranks. The purpose of the heavy cavalry was to directly engage enemy units in close combat. To do their job, Mongol heavy cavalry were heavily armed and armored, much more so than their horse archer counterparts. They were armored head to toe in lamellar armor composed of metal plates sewn together into a suit. Often this armor also covered the horse as well.

Their primary arm was a lance used to conduct charges. For melee fighting they would carry swords or axes, and also maces for armored opponents. They would also probably carry a shield. Along with their horse archer counterparts, Mongol heavy cavalry also carried a bow in order to engage the enemy at a distance. In essence Mongol heavy cavalry were similar to Middle Eastern or Byzantine cataphracts and European mounted knights.

On the battlefield, Mongol units typically fought in five ranks, the first three ranks composed of horse archers, the last two composed of heavy cavalry. During a Mongol charge, the horse archers would close to around 50 - 100 yards and fire arrows while the heavy cavalry would protect them from counterattack by enemy cavalry. It should be noted that Mongol heavy cavalry were also armed with bows, so likewise would be firing on the enemy as well. After firing, the formation would turn around, resupply with arrows, and remount with fresh horses. They would then repeat the charge again and again until eventually the enemy would weaken, begin to panic, lose discipline, and perhaps break ranks. At that point the heavy cavalry would swoop in and smash the enemy formation. The Mongols also used deceptive tactics which the heavy cavalry would be an essential part. One common tactic was the feigned retreat, where a Mongol unit would pretend to retreat in panic as if defeated. The enemy would in turn charge expecting to chase down and massacre a terrified enemy. To their horror, the Mongols would reform and counterattack, the heavy cavalry at the front to smash the disorganized enemy and the horse archers firing from the rear. Another tactic would be to use the horse archers to draw the enemy into an ambush, where the heavy cavalry would appear from a hidden position and conduct a surprise attack on the enemy flanks or rear.

414 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arming Sword from Germany dated to around 1150 on display at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, Scotland

This sword bears the inscriptions: '+ INMNII INP INN +' on one side, on the other, '+INI NNI NNB NN+'.

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#sword#art#archaeology#medieval#12th century#german#germany#military history#kelvingrove art gallery and museum#glasgow#barbucomedie

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Condottiere, early 14th century, by the ever-brilliant Graham Turner.

200 notes

·

View notes

Note

The broken man speech is pretty good writing but does it have any historical basis? Seems like a bad idea to build your army out of smallfolk.

So medieval armies were rarely made entirely out of peasant levies (that's the inaccuracy), even during the storied days of the Anglo-Saxon fyrd at its height. But it was not uncommon for young men to serve as archers in the army - indeed, the entire thrust of English military policy from the 13th through 14th century was to establish as broad and deep a strategic reserve as possible of trained longbowmen for this very reason.

youtube

However, I think it's missing the forest for the trees to focus on the levy model when it comes to the Broken Man speech. Rather, I think it's about the corrosive impact of war on veterans and deserters who fall to banditry due to trauma and a lack of alternatives. It absolutely was a fixture of the Hundred Years' War that unemployed veterans of all nations turned their skills learned in the chevauchées onto civilian populations, causing widespread devastation.

#asoiaf#asoiaf meta#history#historical analysis#medieval history#hundred years war#broken man speech#military history

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

What medieval wars actually looked like

Fantasy media more than anything has created a strange illusion about how people fought in the middle ages and during the wars. That is the idea of people in chain mail, if not full plate armor fighting each other with swords. And... what can I tell you, but... That is not really what fighting in the middle ages looked like.

You have to understand one thing: Outside of Hungary basically no medieval realm had something like a standing army. Meaning, they did not have a lot of trained soldiers. When a king decided to go to war with another realm, for the most part it was just peasants fighting - with a few nobles serving as commanders.

Now, those commanders? Yeah, they had chain mail and at times even full plate armor. But they also tended to be as far away from the front line as possible, if it could be helped. The normal peasant fighting at the front line? Yeah, he could be happy to have a leather jerkin for the most part.

See, you have to see two things. It was very expensive to make armor and weapons - and to be very, very frank, it was more expensive than the life of a peasant was. So why waste precious money and ressources to make those peasants, who were the main fighters in the wars proper armor. Especially given that they would have needed to train to be able to use that armor properly. Which is the second thing. Plate armor especially was super impractical for the most part. It looked fucking impressive, yeah, but...

Well, I talked about it before how I went to LARPs as a cook before, right? And during those LARPs when there was fighting I - the cook - used to stay out of it. But I did one thing at times, because it was just evil and funny. If someone attacked the camp in full plate armor, I would just kamikaze tackle them to the ground - and watch how they would lie there, on their back, like a turtle, unable to get up again.

Full plate armor has its purpose mostly in fighting on horseback. On the ground? It hindered your movement a lot.

And that training? This was part of the reason why people often did not fight with swords (apart from swords again also being kind of expensive): They were not trained to fight with them. So, a lot of people in a medieval battle would usually use whatever they had on hand, meaning you would see a lot of scythes, pitchforks, at times spears (as they could be used for hunting and fishing) and knives. Things that those peasants knew well how to handle.

Oh, and do you want to know one of the most common causes of death in medieval wars (aside from infections)? Drowning in mud. Because often enough once it was raining and a whole army was moving over the fields, those fields would turn to mud. The "soldiers" would sink into the mud and drown.

What I am saying is, that for the most part medieval wars were nothing like what you see in fantasy. And medieval soldiers also looked nothing like a fighter character in DnD would. For the most part this is fine... as long as you do not depict the soldiers like that and then start to argue about "historical accuracy" when it comes to queer people, non-white people or women in regards of the setting.

Though I still would love to see a lot more pole weapons in fantasy, I am completely honest.

#history#middle ages#medieval#medieval history#medieval europe#military history#knights#knight#medieval warfare#fantasy#high fantasy#dungeons & dragons#dnd

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

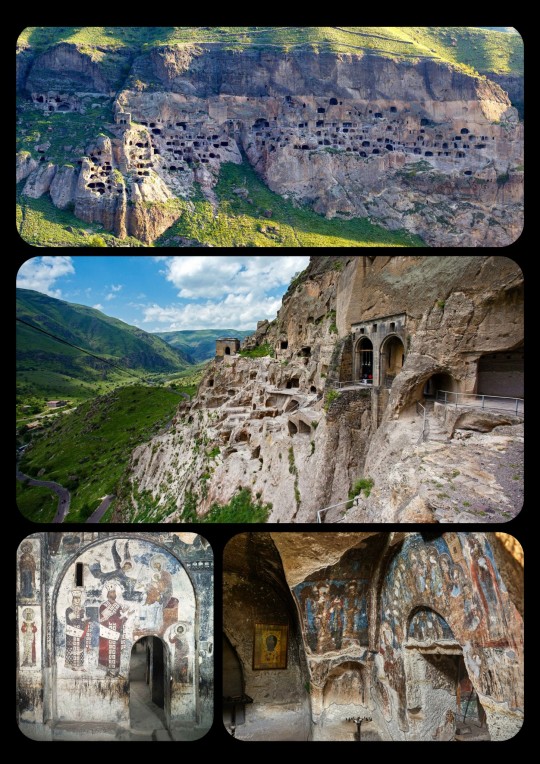

Vardzia, a Medieval Cave City in Georgia (South Caucasus), built in 1150-1200 CE: Vardzia was designed to be used as a fortress/monastery; it was accessible only through hidden passageways, and it contained more than 6,000 caves, 15 chapels, 25 wine cellars, an apothecary, a forge, a bakery, farming terraces, and an irrigation system

The monastic caves at Vardzia cover an area of about 500 meters. They are carved into the cliffs along the Erusheti mountains, which are located in Javakheti (a southern province near the borders between Georgia, Turkey, and Armenia).

Vardzia was originally meant to serve as a fortress, particularly in the event of a Mongol Invasion. It was protected by defensive walls, and the cave system itself was largely concealed within the mountain (though much of it is now exposed); it also contained a secret escape tunnel and several dead-end tunnels that were designed to delay/confuse enemy forces. The cave city could only be accessed through a series of hidden passageways that began near the banks of the Mtkvari River (which runs through the valley below the cave complex). Water was supplied through an irrigation system that was connected to the river, providing the inhabitants with both drinking water and agricultural irrigation, as the site contained its own terraced farmland.

The cave complex also functioned as a monastery, with a large collection of manuscripts and relics ultimately being housed at the site.

In its prime, the complex at Vardzia was inhabited by tens of thousands of residents.

Unfortunately, most of the original structures at Vardzia were destroyed by an earthquake that struck the region in 1283 CE, just a century after its construction; the earthquake sheared away the outer layer of the cliffside, exposed many of the caves, and demolished almost two-thirds of the site. The surviving structures represent only a fraction of the cave complex that once existed at Vardzia, with only about 500 caves still intact.

When the earthquake tore through the site in 1283, much of the fortress and many of its defenses were also destroyed, and Vardzia lost most of its military/defensive purposes. Still, it continued to operate as a Georgian Orthodox monastery for several hundred years after that. It narrowly escaped the Mongol Invasions of the 1290s, but it was raided by the Persians during the 16th century; the invading forces burned many of the manuscripts, relics, and other items that were stored within the cave system, leaving permanent scorch marks along the walls of the inner chambers. The site was abandoned shortly thereafter.

Medieval portrait of Queen/King Tamar: this portrait is one of the Medieval frescoes that still decorate the inner chambers of Vardzia; Tamar was the first queen regnant to rule over Georgia, meaning that she possessed the same power/authority as a king and, as a result, some Medieval sources even refer to her as "King Tamar"

Vardzia is often associated with the reign of Queen Tamar the Great, who ruled over the Kingdom of Georgia from 1184 to 1213 CE, during a particularly successful period that is often known as the "Golden Age" of Georgian history. Queen Tamar was also recognized as the Georgian King, with Medieval sources often referring to her as King Tamar. She possessed the powers of a sovereign leader/queen regnant, and was the first female monarch to be given that title in Georgia.

The initial phases of construction at Vardzia began under the command of King George III, but most of the complex was later built at the behest of his daughter, Queen Tamar, who owned several dedicated rooms at Vardzia and frequently visited the cave city. Due to her relationship with the cave complex at Vardzia, Queen Tamar is sometimes also referred to as the "Mountain Queen."

Despite the damage that the site has sustained throughout its history, many of the caves, tunnels, frescoes, and other structures have survived. The site currently functions as a monastery once more, with Georgian monks living in various chambers throughout the cave system.

I visited Vardzia back in 2011, during my first trip to Georgia. It's an incredible site, though some of the tunnels are very narrow, very dark, and very steep, which can get a bit claustrophobic.

Sources & More Info:

Atlas Obscura: Vardzia Cave Monastery

CNN: Exploring Vardzia, Georgia's Mysterious Rock-Hewed Cave City

Lonely Planet: Vardzia

Globonaut: 5 Facts about Vardzia, Georgia's Hidden Cave City

Wander Lush: Vardzia Cave Monastery (complete visitor's guide)

#archaeology#anthropology#history#vardzia#georgia#caucasus#cave city#cave complex#monastic caves#artifact#architecture#military history#Tamar#religon#comparative religion#medieval fortress#middle ages#medieval church#medieval europe#travel#I think I'd need#all 25 wine cellars#just to get through a Mongol invasion

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horse archery and heavy cavalry

While many tend to associate heavily armoured cavalry with tactics similar to Europe in that they are solely lancers, meant to charge into enemy formations and break them, in most of the world heavy cavalry didn't tend to serve solely this role. In essentially all of Asia heavy cavalry tended to be equipped with bows and served the same role as more lightly armoured horse archers while also being able to double as shock cavalry when the situation called for it due to their heavier equipment. These tactics were also adopted in North Africa, due to direct influence from the Turkic slave soldiers in use by the Islamic caliphates.

Of course many people do tend to associate horse archery with lighter cavalry and this is understandable as most horse archers did tend to be more lightly equipped in the steppe armies. But this isn't because they're horse archers, but rather the opposite. Because it was the default for cavalry to be archers, and when one is lightly armoured the best role to serve would be that of a horse archer. However by no means does horse archery require lightly armoured troops.

One specific way of utilizing heavy cavalry, popular all across central and west Asia though by no means limited to it, would be to equip heavy cavalry with lances in addition to their bows. The most famous users of this tactic would probably be the Mongols which made very liberal and effective use of their heavy cavalry in this manner. The cavalry would serve the regular horse archer role at first - harrassing the enemy at range - but when the situation called for it they'd swap to their lances and charge into the weary enemy ranks. If the enemy didn't break immediately (which they often did) they'd pull back, regroup and charge again.

This might then raise the question in some of you which is - how does one carry both a bow and a lance at the same time? Luckily for us, we have got sources for this. Below is a depiction from an early 14th century Ilkhanate manuscript, depicting the lance tied around the foot and arm to leave the hands free for bow- or indeed in this case sword - usage.

Another source for how to hold a lance while using a bow on horseback can be found in the Silahşorname by the late 15th century Ottoman author, Firdevsî-i Rûmî. The translation below was done by a friend of mine:

"The second way is that if you wish to shoot arrows while on top of a running horse, whether it be in battle against an enemy or other places or in hunting, then it’s necessary to secure the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest while making the horse run. That is to say, put the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest and tuck its blade high up. As in tuck the lance into your right elbow and have the blade of the lance behind you so that it stays secure. And after that, your horse can run and you can make your shot. Shooting arrows in this way is the legacy of Behram-i Gur, who was the sultan of Persia, he was a hunter and an archer."

The attribution of this technique to the 5th century Behram-i Gur is definitely a fabrication by the author of the book, no doubt to mythicise the usage of the weaponry in this manner. regardless, the technique mentioned is pretty interesting.

While there's scores more to say about this topic I think leaving it here for this time is good enough. I will however leave you with a video series below which is an extremely well researched overview on heavy cavalry in the Mongol armies, and definitely a must watch if you have any interest in this topic.

youtube

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

#knights templar#templar#templars#art#medieval#crusades#middle ages#europe#history#european#christianity#military#knights#knight#armour#jerusalem#temple mount#crusader#crusaders#crusade#christendom#deus vult#christian#in hoc signo vinces#imperium#flags#flag

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

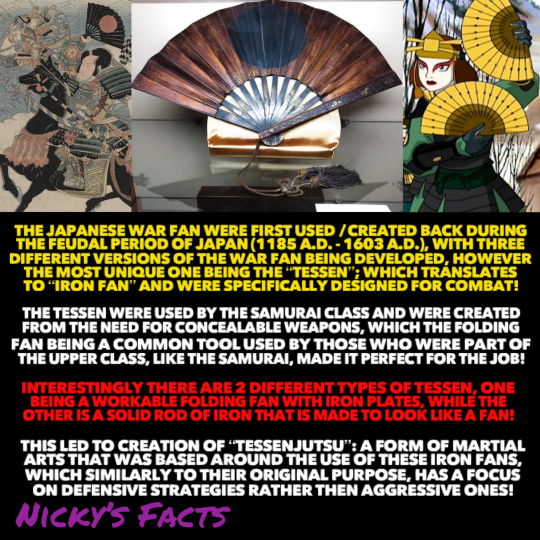

The Kyoshi Warriors are way more realistic then most people realize!🪭

#history#japanese war fan#kyoshi warriors#tessen#samurai#japanese history#tessenjutsu#self defense#feudal japan#avatar the last airbender#atla#military history#folding fan#medieval#girl power#kioshi#fight like a girl#femininity#nickelodeon#japan#weapon#martial arts#nickys facts

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Like Bjorn Ironside pretending to be dead and getting his coffin only to suppress attack, what’s the coolest battle/fight tactics in history?

I'm going to preface this with the fact that 1) There are too many to list here (or anywhere really) and 2) I'm limited to what I personally know.

That said, here are a few that spring to mind:

Richard III's last charge at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Not only did he get within a sword's length of killing Henry Tudor himself but Richard also killed Henry's standard-bearer, Sir William Brandon, AND unhorsed burly John Cheyne, his older brother's former standard-bearer. Not bad for a guy who would today qualify for the Special Olympics. (The Japanese equivalent would be Sanada Yukimura.)

Harold Godwinson marching his army 185 miles (or 298 km) in just four days to take the Norwegians by surprise at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. (Honorable mention goes to the soldier who got in a barrel and floated under the bridge to spear the Viking holding off the entire English army. Chevalier de Bayard, a real life knight in shining armor, later replicated this feat by holding off 200 Spanish knights single-handedly at the Battle of Garigliano.)

When the rebels started chanting "Henry Percy King" at the Battle of Shrewsbury, Henry IV shouted back "Henry Percy is dead." Needless to say, Henry Percy did not respond. (His eldest son, the future Henry V (or as Shakespeare names him in his youth, Prince Hal), took an arrow to the face in this same battle, which is why Henry V's portraits always depict him from his uninjured side.)

Hannibal crossing the Alps and whooping Rome's ass multiple times on its own turf. (There's a reason "Hannibal ad portas" became a saying. Also, Napoleon I later replicated this feat.)

At the Battle of Bremule, a Norman knight seized the reins of Louis the Fat's horse, shouting "the king is taken!" Louis' response? Hitting the guy with his mace and shouting "the king is not taken, neither at war, nor at chess!"

Alexander the Great turning the island city of Tyre into a peninsula.

Alexander Buchanan killing Thomas, Duke of Clarence at the Battle of Bauge and holding the dead duke's coronet aloft on his lance.

Thanks for the question, anon

#history#military history#english history#french history#scottish history#ancient history#medieval history#renaissance history#japanese history#sengoku jidai#warring states period#hundred years war#wars of the roses#the italian wars#punic wars#napoleon bonaparte#hannibal barca#alexander the great#chevalier de bayard#william shakespeare

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armor: Beyond the Extants

The casual study of armor is dominated by an obsession with the extants, the surviving elements of armor that have been preserved in museums, private collections, and armories or that have been recovered archaeologically. While these pieces remain an invaluable source of information for scholars and laymen alike, there are a great many things they cannot tell us. In order to fill in these gaps in the record, scholars in the study of armor make heavy use of both artistic depictions of armor and the historical record, each of which brings its own advantages and disadvantages. Artwork is a particularly valuable resource, as it allows scholars to see precisely what the artist intended, without the vagaries of interpretation frequently left in the historical record.

There are many disparate kinds of artistic works from the medieval and early modern periods which depict armor and are used by scholars of armor. Here, they will be divided into three broad categories: Paintings, Sculpture, and The Rest.

Paintings

Paintings are among the most commonly utilized and widely recognized forms of medieval artwork. Here, the term “painting” is used in a broad sense; while this category does include the typical paint on canvas framed upon a wall, other varieties of painted works are also included.

Portraits are some of the most instantly recognizable forms of painting. Typically in the traditional form, many wealthy and influential men have had their portraits painted over the years, a tradition that lasts even to this day. The practice of being painted in one’s armor is one that came to be common in the 16th century. The portrait pictured below depicts Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara and a commander in the Italian Wars.

The portrait of Alfonso d’Este radiates wealth, power, and military prowess. Trimmed with gold, his armor represents the height of Italian fashion. The golden chain hanging around his neck displays even more wealth, as well as clearly marking him as a military man and a member of the prestigious knightly order of St. Michael. His surcote is made from an expensive blue silk velvet, and his gilded sword suspended by a blue silken sash. In one hand, he wields a gilded mace (a stand-in for the baton of command, a typical symbol of authority at this time), while the other rests upon the muzzle of a cannon. Though his gauntlets are doffed, they are placed prominently on the table before him, and in the background a battle rages.

This portrait speaks to many things which could not otherwise be known. Even had this armor which Alfonso wore survived, the velvet surcote almost certainly would not have. Additionally, many surviving elements of armor have had their decoration fade over time, or be scrubbed clean by modern collectors. The gilding which decorates this armor may also have never been known to us.

Portraits such as this one are invaluable, and extremely reliable, references for the study of any material culture, including armor. Typically, the portrait depicts what the artist had seen, what actually lay before them. They leave little room for misinterpretation. This is in contrast to our second category of painting.

Religious and Historical Paintings were common throughout the medieval period and well into the 16th century. This category generally includes framed paintings, frescoes, and painted altarpieces. While the paintings of this category are extremely prevalent, and common across the entire medieval period, they require a special degree of caution. While many religious paintings depict religious and historical figures in gear contemporary to the time the figure was painted (see below, an altar panel depicting the Saints George and Sebastian painted c. 1507-1510) some artists also made attempts to make their scenes feel more ancient to a medieval audience.

Below is pictured a detail from the Santa Croce altarpiece, painted between 1325 and 1328 by Ugolino di Nerio. This particular panel depicts the betrayal of Judas and the arrest of Jesus by Roman troops. The Romans in question are depicted in a mix of contemporary and fantastical equipment. The feathered frills on the Roman’s arms and skirts (sometimes called pteruges) are indicative of this fantastical style, and the closely-fitted, almost muscular garments the soldiers wear over their bodies are meant to mimic the “heroic” muscled figures of classical sculpture, indicating an ancient scene to the medieval viewer.

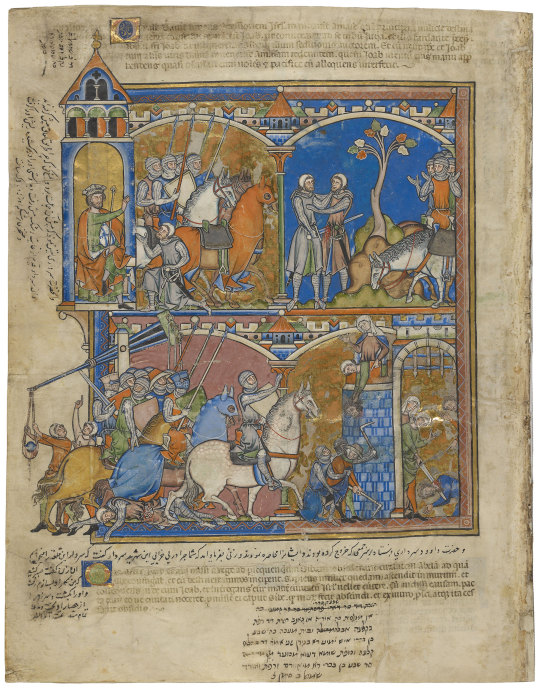

The final category of painting which will be discussed here is the Miniature. While miniatures often contain religious or historical imagery, and so are subject to the same needs for caution as listed above, they operate by different enough rules to warrant their own discussion.

Miniatures are a form of marginalia, tiny paintings added into the margins of manuscripts. As such, though they frequently bear incredible levels of detail for such small works of art, they leave much room for error and interpretation. Miniatures are extremely plentiful, and a very popular source for the study of armor, and when utilized with the appropriate degree of caution, they are indispensable.

Perhaps among the most famous manuscript miniatures are those in MS M.638 at the Morgan Library in New York City. Also called the Maciejowski Bible, or the Crusader Bible, MS M.638 was made in Paris in the 1240’s. Filled with remarkable illustrations, this manuscript is an incredible source for all manner of 13th century material culture, but is especially well renowned for its depictions of 13th century knights and men-at-arms.

Sculpture

In the category of sculpture, we will first discuss Architectural Sculpture. While with all pieces of art it is best to determine when the individual piece was made, this is particularly true for architectural sculpture. For instance: pictured below is a piece of sculpture off of the Santissima Annuziata in Florence. Though this church was originally built around 1250, it has since been renovated many times. This piece of stonework is not a part of the original structure, but instead was added during one of the renovations. As such, this sculpture does not date to the middle of the 13th century, but instead to the first half of the 14th century, and is representative of military equipment of that time.

The second sculptural category is Effigies. A form of artwork that has seen a recent intensification in use by armor scholars thanks to the Armour of the English Knight series by Dr. Tobias Capwell, effigies (which are typically carved in stone, alabaster, wood, or even bronze) represent a particular individual. Much like portraits, effigies are extremely reliable sources for armor. In his first book, Armour of the English Knight 1400-1450, Dr. Capwell includes an essay defending the accuracy of effigies. He states:

Concepts of purgatory and the way that it worked developed substantially during the twelfth century, with one of the central principles becoming this link between the living and the dead. The living could come to the aid of the dead through intercession- the offering of prayers for the departed soul. As Saul has shown, effigies were intended to work as a kind of intercessionary lens, focusing memories of the deceased and thus facilitating the success of the prayers on their behalf.

As such it was the effigy sculptor's spiritual duty to create a sculpture which was as close to real life as possible, so as to aid the departed soul on its path through purgatory. Frequently, these effigies were even painted. Pictured below is the effigy of Thurstan de Bower at the church of St. John the Baptist in Tideswell, England, dated to 1423.

Like other forms of sculpture, however, it pays to know when the effigy was made. In many cases, the effigy was commissioned either before the individual’s death or after by their loved ones. Very rarely does an effigy actually precisely represent the year of the individual’s death, and typically the effigy will present armor contemporary to the time of its manufacture, not the time of the deceased individual’s death.

Many other forms of sculpture persist from the middle ages which occasionally depict martial material culture. Commonly altar pieces carved from wood and alabaster survive, as do statues of saints and other similar sculptural elements. These sculptures follow the same rules as listed above in regards to their usefulness and elements to be weary of.

The Rest

With the primary sources covered, it’s time to move on to The Rest. While the above constitute the most important and most consistently utilized artistic sources for the study of armor, they are by no means the only sources. The armor-clad man-at-arms was central to the image of the ruling medieval class, and as such it suffused every aspect of medieval art. Men-at-arms may be seen in tapestries,

on eating ware,

and even on gaming boards.

What’s important is that, no matter the source, you approach it with a keen, critical eye and that you never stop looking.

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sword Hilt and Portion of Blade Excavated from the Isle of Man dated between the 13th-14th Centuries on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh Scotland

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#sword#medieval#military history#archaeology#art#scotland#scottish#national museum of scotland#edinburgh#barbucomedie

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behold the glorious artwork of Angus McBride, depicting two scenes from the battle of Stirling Bridge, fought by Scottish and English forces on 11 September 1297.

In the first piece, William Wallace (right) rejects two Bendictine monks sent by the English to negotiate while another Scottish noble, Andrew Moray, (left) looks on. It is likely that Moray, with higher social standing, more military experience and more men under his command, was actually the leader of the Scottish forces during the battle, and not Wallace. According to Medieval chronicler Walter of Guisborough the Scots rejected the English offers with the following statement (though he doesn't specify if it was Wallace or Moray doing the talking);

“Go back and tell your men that we come not for the good of peace, but we are ready to fight to defend ourselves and free our realm! Therefore, let them advance when they wish, and they will find us ready to fight them even into their beards!”

The English attempted to ford the river beneath Stirling Castle - crossable only via a narrow timber bridge - and were set upon by the Scots with half their force still on the opposite bank. A slaughter of the English ensued, accentuated when the bridge itself collapsed. In the lower artwork Wallace can be seen on the left and Moray on the right, leading the attack on the English knights. The slightly corpulent Englishman on foot before Moray with the three black swans as his heraldry is Hugh de Cressingham, the second-in-command of the English force and one of the men responsible for administering the English occupation of Scotland. He was killed and after the battle, according to several chroniclers, his body was flayed in revenge for the tortures he had inflicted upon the Scots. Part of him was used by Wallace to make a scabbard for his sword; "of his skin William Wallace caused a broad strip to be taken from the head to the heel, to make therewith a baldrick for his sword."

tl;dr look at this badass artwork of William Wallace being depicted historically and not in Dumbass Fantasy Mode.

#history#medieval history#stirling bridge#battle of stirling bridge#scottish wars of independence#william wallace#andrew moray#13th century#knight#knights#military history

62 notes

·

View notes