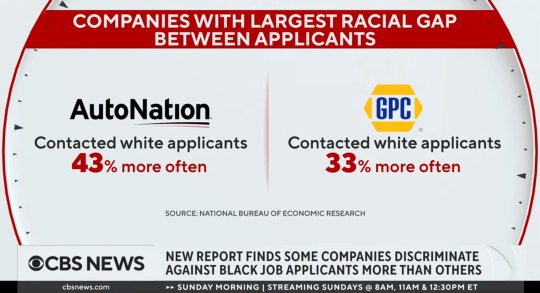

#National Bureau of Economic Research

Text

youtube

#we been knew study#employment discrimination#anti blackness#National bureau of economic research#a discrimination report card#Evan rose#cbs#youtube#video#no image description

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economist Lisa Cook Confirmed to Federal Reserve Board, 1st Black Woman Governor in Agency's 108-Year History

Economist Lisa Cook Confirmed to Federal Reserve Board, 1st Black Woman Governor in Agency’s 108-Year History

According to washingtonpost.com, economist Lisa Cook was confirmed today to serve on the Federal Reserve Board.

She is the first Black woman to help oversee the nation’s central bank as it works to stabilize financial recovery in the United States.

To quote from washingtonpost.com:

Cook was confirmed by a 51-to-50 vote in the Senate, with Vice President Harris casting the tiebreaking vote.

No…

View On WordPress

#Federal Reserve Board#Jim Crow laws#Lisa Cook#Michigan State University#National Bureau of Economic Research#University of Michigan#Vice President Harris#White House’s Council of Economic Advisers

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

“During the Middle Ages, an English laborer had to work 80 hours to pay for a pound of sugar. By 2021, an English laborer had to work only 1.89 minutes to do that. In 1800, it took 5.4 hours of work to buy 1,000 lumen-hours; in 1992, it took only 0.00012 hours of work for someone to light their home for six weeks.”

- David Brooks, The Atlantic, January 13, 2023

0 notes

Text

Confederate Descendants Spread Racism, Infect the Supreme Court, and Roll Back Civil Rights

John Roberts is just the latest generation of white supremacists dedicated to promoting the Confederacy, pro-slavery norms, and anti-democratic beliefs. There is a long sad history here traced by Rachel Maddow on Deja News and a study on culture

SUMMARY: There is a through line of white supremacy, racism, and pro-slavery views connecting the three-fifths compromise, the Civil War, Jim Crow, and Trump. This post uses the third episode of Rachel Maddow Presents and a study on the geography of culture to make the connections between past efforts to oppress Black and Hispanic Americans to our current installment of the ascendance of white…

View On WordPress

#Civil Rights#Color-Blind Society#Confederate Descendents#Confederate Diaspora#Consent Decree#Deja News#Isaac-Davy Aronson#Jim Crow#John Roberts#National Bureau of Economic Research#NBCNews#Operation Eagle Eye#Podcast#Rachel Maddow#Racism#SCOTUS#Supreme Court#The Confederacy#Voter Suppression#White Supremacy#William H. Rehnquist

0 notes

Text

The National Bureau of Economic Research just put out a new study today showing that twice as many Republicans were killed by Covid as Democrats

with the incredibly narrow margins in the midterm races, I can't help but wonder if this year might have instead seen dramatic victories for the right

except for the fact that hundreds of thousands of GOP voters are now dead and in the ground

all because the pandemic was "not a big deal", "under control", "a hoax", "a conspiracy", etc.

#2022#us#united states#covid#covid19#pandemic#public#health#NBER#national bureau of economic research#republican#republicans#democrat#democrats#midterm#elections#donald trump#misinformation#just a complete waste of life#well done#hope you're proud of yourself

1 note

·

View note

Text

Engaging Teachers With Technology Increased Achievement, Bypassing Teachers Did Not

Engaging Teachers With Technology Increased Achievement, Bypassing Teachers Did Not

Engaging Teachers With Technology Increased Achievement, Bypassing Teachers Did NotDownload

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Writer Spotlight: Elise Hu

We recently met with Elise Hu (@elisegoeseast) to discuss her illuminating title, Flawless—Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital. Elise is a journalist, podcaster, and media start-up founder. She’s the host of TED Talks Daily and host-at-large at NPR, where she spent nearly a decade as a reporter. As an international correspondent, she has reported stories from more than a dozen countries and opened NPR’s first-ever Seoul bureau in 2015. Previously, Elise helped found The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit digital start-up, after stops at many stations as a television news reporter. Her journalism work has won the national Edward R. Murrow and duPont Columbia awards, among others. An honors graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism, she lives in Los Angeles.

Can you begin by telling us a little bit about how Flawless came to be and what made you want to write about K-beauty?

It’s my unfinished business from my time in Seoul. Especially in the last year I spent living in Korea, I was constantly chasing the latest geopolitical headlines (namely, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s big moves that year). It meant I didn’t get to delve into my nagging frustrations of feeling second-class as an Asian woman in Korea and the under-reported experiences of South Korean women at the time. They were staging record-setting women’s rights rallies during my time abroad in response to a stark gender divide in Korea. It is one of the world’s most influential countries (and the 10th largest economy) and ranks shockingly low on gender equality metrics. That imbalance really shows up in what’s expected of how women should look and behave. Flawless explores the intersection of gender politics and beauty standards.

Flawless punctuates reportage with life writing, anchoring the research within your subjective context as someone who lived in the middle of it but also had an outside eye on it. Was this a conscious decision before you began writing?

I planned to have fewer of my personal stories in the book, actually. Originally, I wanted to be embedded with South Korean women and girls who would illustrate the social issues I was investigating, but I wound up being the narrative thread because of the pandemic. The lockdowns and two years of long, mandatory quarantines in South Korea meant that traveling there and staying for a while to report and build on-the-ground relationships was nearly impossible. I also have three small children in LA, so the embedding plan was scuttled real fast.

One of the central questions the book asks of globalized society at large, corporations, and various communities is, “What is beauty for?” How has your response to this question changed while producing Flawless?

I think I’ve gotten simultaneously more optimistic and cynical about it. More cynical in that the more I researched beauty, the more I understood physical beauty as a class performance—humans have long used it to get into rooms—more power in relationships, social communities, economically, or all of the above at once. And, as a class performance, those with the most resources usually have the most access to doing the work it takes (spending the money) to look the part, which is marginalizing for everyone else and keeps lower classes in a cycle of wanting and reaching. On the flip side, I’m more optimistic about what beauty is for, in that I have learned to separate beauty from appearance: I think of beauty in the way I think about love or truth, these universal—and largely spiritual—ideas that we all seek, that feed our souls. And that’s a way to frame beauty that isn’t tied in with overt consumerism or having to modify ourselves at all.

This is your first book—has anything surprised you in the publishing or publicity process for Flawless?

I was most surprised by how much I enjoyed recording my own audiobook! I felt most in flow and joyful doing that more than anything else. Each sentence I read aloud was exactly the way I heard it in my head when I wrote it, which is such a privilege to have been able to do as an author.

Do you have a favorite reaction from a reader?

I don’t know if it’s the favorite, but recency bias is a factor—I just got a DM this week from a woman writing about how the book helped put into words so much of what she felt and experienced, despite the fact she is not ethnically Korean, or in Korea, which is the setting of most of the book. It means a lot to me that reporting or art can connect us and illuminate shared experiences…in this case, learning to be more embodied and okay with however we look.

As a writer, journalist, and mother—how did you practice self-care when juggling work commitments, social life, and the creative processes of writing and editing?

I juggled by relying on my loved ones. I don’t think self-care can exist without caring for one another, and that means asking people in our circles for help. A lot of boba dates, long walks, laughter-filled phone calls, and random weekend trips really got me through the arduous project of book writing (more painful than childbirth, emotionally speaking).

What is your writing routine like, and how did the process differ from your other reporting work? Did you pick up any habits that you’ve held on to?

My book writing routine was very meandering, whereas my broadcast reporting and writing are quite linear. I have tight deadlines for news, so it’s wham, bam, and the piece is out. With the book, I had two years to turn in a manuscript. I spent the year of lockdowns in “incubation mode,” where I consumed a lot of books, white papers, articles, and some films and podcasts, just taking in a lot of ideas to see where they might collide with each other and raise questions worth reporting on, letting them swim around in the swamp of my brain. When I was ready to write, I had a freelance editor, the indefatigable Carrie Frye, break my book outline into chunks so I could focus on smaller objectives and specific deadlines. Chunking the book so it didn’t seem like such a massive undertaking helped a lot. As for the writing, I never got to do a writer’s retreat or some idyllic cabin getaway to write. I wrote in the in-between moments—a one or two hour window when I had a break from the TED conference (which I attend every year as a TED host) or in those moments after the kids’ bedtime and before my own. One good habit I got into was getting away from my computer at midday. I’m really good about making lunch dates or going for a run to break up the monotony of staring at my screen all day long.

What’s good advice you’ve received about journalism that you would pass on to anyone just starting out?

All good reporting comes from great questions. Start with a clear question you seek to answer in your story, project, or book, and stay true to it and your quest to answer it. Once you are clear on what the thing is about, you won’t risk wandering too far from your focal point.

Thanks to Elise for answering our questions! You can follow her over at @elisegoeseast and check out her book Flawless here!

#writer spotlight#elise hu#flawless#k-beauty#beauty#beauty industry#feminism#gender politics#seoul#south korea#journalism#writing advice#reportage#flawlessthebook

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

The global COVID-19 vaccination campaign saved 2.4 million lives in 141 countries and could have saved about 670,000 more had the vaccines been distributed equitably, say researchers.

The findings come from a working paper circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research prior to peer review.

The benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines are far-reaching by multiple measures, says coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, an associate professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown University.

“Our study shows the enormous health impacts of COVID-19 vaccines, which in turn have huge economic benefits,” Whaley says. “In terms of lives saved and economic value, the COVID-19 vaccination campaign is likely the most impactful public health response in recent memory.”

Continue Reading.

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

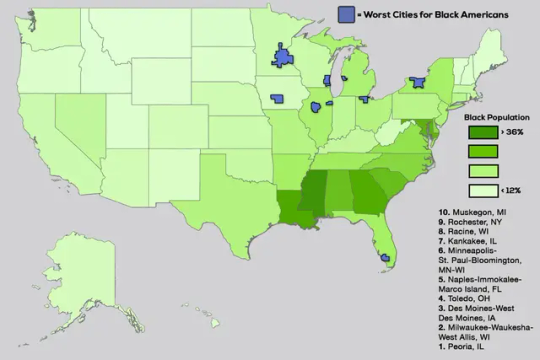

Where It’s Most Dangerous to Be Black in America

Black Americans made up 13.6% of the US population in 2022 and 54.1% of the victims of murder and non-negligent manslaughter, aka homicide. That works out, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, to a homicide rate of 29.8 per 100,000 Black Americans and four per 100,000 of everybody else.(1)

A homicide rate of four per 100,000 is still quite high by wealthy-nation standards. The most up-to-date statistics available from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development show a homicide of rate one per 100,000 in Canada as of 2019, 0.8 in Australia (2021), 0.4 in France (2017) and Germany (2020), 0.3 in the UK (2020) and 0.2 in Japan (2020).

But 29.8 per 100,000 is appalling, similar to or higher than the homicide rates of notoriously dangerous Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. It also represents a sharp increase from the early and mid-2010s, when the Black homicide rate in the US hit new (post-1968) lows and so did the gap between it and the rate for everybody else. When the homicide rate goes up, Black Americans suffer disproportionately. When it falls, as it did last year and appears to be doing again this year, it is mostly Black lives that are saved.

As hinted in the chart, racial definitions have changed a bit lately; the US Census Bureau and other government statistics agencies have become more open to classifying Americans as multiracial. The statistics cited in the first paragraph of this column are for those counted as Black or African American only. An additional 1.4% of the US population was Black and one or more other race in 2022, according to the Census Bureau, but the CDC Wonder (for “Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research”) databases from which most of the statistics in this column are drawn don’t provide population estimates or calculate mortality rates for this group. My estimate is that its homicide rate in 2022 was about six per 100,000.

A more detailed breakdown by race, ethnicity and gender reveals that Asian Americans had by far the lowest homicide rate in 2022, 1.6, which didn’t rise during the pandemic, that Hispanic Americans had similar homicide rates to the nation as a whole and that men were more than four times likelier than women to die by homicide in 2022. The biggest standout remained the homicide rate for Black Americans.

Black people are also more likely to be victims of other violent crime, although the differential is smaller than with homicides. In the 2021 National Crime Victimization Survey from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (the 2022 edition will be out soon), the rate of violent crime victimization was 18.5 per 1,000 Black Americans, 16.1 for Whites, 15.9 for Hispanics and 9.9 for Asians, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Understandably, Black Americans are more concerned about crime than others, with 81% telling Pew Research Center pollsters before the 2022 midterm elections that violent crime was a “very important” issue, compared with 65% of Hispanics and 56% of Whites.

These disparities mainly involve communities caught in cycles of violence, not external predators. Of the killers of Black Americans in 2020 whose race was known, 89.4% were Black, according to the FBI. That doesn’t make those deaths any less of a tragedy or public health emergency. Homicide is seventh on the CDC’s list of the 15 leading causes of death among Black Americans, while for other Americans it’s nowhere near the top 15. For Black men ages 15 to 39, the highest-risk group, it’s usually No. 1, although in 2022 the rise in accidental drug overdoses appears to have pushed accidents just past it. For other young men, it’s a distant third behind accidents and suicides.

To be clear, I do not have a solution for this awful problem, or even much of an explanation. But the CDC statistics make clear that sky-high Black homicide rates are not inevitable. They were much lower just a few years ago, for one thing, and they’re far lower in some parts of the US than in others. Here are the overall 2022 homicide rates for the country’s 30 most populous metropolitan areas.

Metropolitan areas are agglomerations of counties by which economic and demographic data are frequently reported, but seldom crime statistics because the patchwork of different law enforcement agencies in each metro area makes it so hard. Even the CDC, which gets its mortality data from state health departments, doesn’t make it easy, which is why I stopped at 30 metro areas.(2)

Sorting the data this way does obscure one key fact about homicide rates: They tend to be much higher in the main city of a metro area than in the surrounding suburbs.

But looking at homicides by metro area allows for more informative comparisons across regions than city crime statistics do, given that cities vary in how much territory they cover and how well they reflect an area’s demographic makeup. Because the CDC suppresses mortality data for privacy reasons whenever there are fewer than 10 deaths to report, large metro areas are good vehicles for looking at racial disparities. Here are the 30 largest metro areas, ranked by the gap between the homicide rates for Black residents and for everybody else.

The biggest gap by far is in metropolitan St. Louis, which also has the highest overall homicide rate. The smallest gaps are in metropolitan San Diego, New York and Boston, which have the lowest homicide rates. Homicide rates are higher for everybody in metro St. Louis than in metro New York, but for Black residents they’re six times higher while for everyone else they’re just less than twice as high.

There do seem to be some regional patterns to this mayhem. The metro areas with the biggest racial gaps are (with the glaring exception of Portland, Oregon) mostly in the Rust Belt, those with the smallest are mostly (with the glaring exceptions of Boston and New York) in the Sun Belt. Look at a map of Black homicide rates by state, and the highest are clustered along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. Southern states outside of that zone and Western states occupy roughly the same middle ground, while the Northeast and a few middle-of-the-country states with small Black populations are the safest for their Black inhabitants.(3)

Metropolitan areas in the Rust Belt and parts of the South stand out for the isolation of their Black residents, according to a 2021 study of Census data from Brown University’s Diversity and Disparities Project, with the average Black person living in a neighborhood that is 60% or more Black in the Detroit; Jackson, Mississippi; Memphis; Chicago; Cleveland and Milwaukee metro areas in 2020 (in metro St. Louis the percentage was 57.6%). Then again, metro New York and Boston score near the top on another of the project’s measures of residential segregation, which tracks the percentage of a minority group’s members who live in neighborhoods where they are over-concentrated compared with White residents, so segregation clearly doesn’t explain everything.

Looking at changes over time in homicide rates may explain more. Here’s the long view for Black residents of the three biggest metro areas. Again, racial definitions have changed recently. This time I’ve used the new, narrower definition of Black or African American for 2018 onward, and given estimates in a footnote of how much it biases the rates upward compared with the old definition.

All three metro areas had very high Black homicide rates in the 1970s and 1980s, and all three experienced big declines in the 1990s and 2000s. But metro Chicago’s stayed relatively high in the early 2010s then began a rebound in mid-decade that as of 2021 had brought the homicide rate for its Black residents to a record high, even factoring in the boost to the rate from the definitional change.

What happened in Chicago? One answer may lie in the growing body of research documenting what some have called the “Ferguson effect,” in which incidents of police violence that go viral and beget widespread protests are followed by local increases in violent crime, most likely because police pull back on enforcement. Ferguson is the St. Louis suburb where a 2014 killing by police that local prosecutors and the US Justice Department later deemed to have been in self-defense led to widespread protests that were followed by big increases in St. Louis-area homicide rates. Baltimore had a similar viral death in police custody and homicide-rate increase in 2015. In Chicago, it was the October 2014 shooting death of a teenager, and more specifically the release a year later of a video that contradicted police accounts of the incident, leading eventually to the conviction of a police officer for second-degree murder.

It’s not that police killings themselves are a leading cause of death among Black Americans. The Mapping Police Violence database lists 285 killings of Black victims by police in 2022, and the CDC reports 209 Black victims of “legal intervention,” compared with 13,435 Black homicide victims. And while Black Americans are killed by police at a higher rate relative to population than White Americans, this disparity — 2.9 to 1 since 2013, according to Mapping Police Violence — is much less than the 7.5-to-1 ratio for homicides overall in 2022. It’s the loss of trust between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve that seems to be disproportionately deadly for Black residents of those communities.

The May 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer was the most viral such incident yet, leading to protests nationwide and even abroad, as well as an abortive local attempt to disband and replace the police department. The Minneapolis area subsequently experienced large increases in homicides and especially homicides of Black residents. But nine other large metro areas experienced even bigger increases in the Black homicide rate from 2019 to 2022.

A lot of other things happened between 2019 and 2022 besides the Floyd protests, of course, and I certainly wouldn’t ascribe all or most of the pandemic homicide-rate increase to the Ferguson effect. It is interesting, though, that the St. Louis area experienced one of the smallest percentage increases in the Black homicide rate during this period, and it decreased in metro Baltimore.

Also interesting is that the metro areas experiencing the biggest percentage increases in Black residents’ homicide rates were all in the West (if your definition of West is expansive enough to include San Antonio). If this were confined to affluent areas such as Portland, Seattle, San Diego and San Francisco, I could probably spin a plausible-sounding story about it being linked to especially stringent pandemic policies and high work-from-home rates, but that doesn’t fit Phoenix, San Antonio or Las Vegas, so I think I should just admit that I’m stumped.

The standout in a bad way has been the Portland area, which had some of the longest-running and most contentious protests over policing, along with many other sources of dysfunction. The area’s homicide rate for Black residents has more than tripled since 2019 and is now second highest among the 30 biggest metro areas after St. Louis. Again, I don’t have any real solutions to offer here, but whatever the Portland area has been doing since 2019 isn’t working.

(1) The CDC data for 2022 are provisional, with a few revisions still being made in the causes assigned to deaths (was it a homicide or an accident, for example), but I’ve been watching for weeks now, and the changes have been minimal. The CDC is still using 2021 population numbers to calculate 2022 mortality rates, and when it updates those, the homicide rates will change again, but again only slightly. The metropolitan-area numbers also don’t reflect a recent update by the White House Office of Management and Budget to its list of metro areas and the counties that belong to them, which when incorporated will bring yet more small mortality-rate changes. To get these statistics from the CDC mortality databases, I clicked on “Injury Intent and Mechanism” and then on “Homicide”; in some past columns I instead chose “ICD-10 Codes” and then “Assault,” which delivered slightly different numbers.

(2) It’s easy to download mortality statistics by metro area for the years 1999 to 2016, but the databases covering earlier and later years do not offer this option, and one instead has to select all the counties in a metro area to get area-wide statistics, which takes a while.

(3) The map covers the years 2018-2022 to maximize the number of states for which CDC Wonder will cough up data, although as you can see it wouldn’t divulge any numbers for Idaho, Maine, Vermont and Wyoming (meaning there were fewer than 10 homicides of Black residents in each state over that period) and given the small numbers involved, I wouldn’t put a whole lot of stock in the rates for the Dakotas, Hawaii, Maine and Montana.

(https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/14/where-it-s-most-dangerous-to-be-black-in-america/cdea7922-52f0-11ee-accf-88c266213aac_story.html)

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Average excess death rates in Florida and Ohio were 76% higher among Republicans than Democrats from March 2020 to December 2021, according to a working paper released last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Excess deaths refers to deaths above what would be anticipated based on historical trends.

A study in June published in Health Affairs similarly found that counties with a Republican majority had a greater share of Covid deaths through October 2021, relative to majority-Democratic counties.

[...]

Indeed, his paper found that the partisan gap in the deaths widened from April to December 2021, after all adults became eligible for Covid vaccines. Excess death rates in Florida and Ohio were 153% higher among Republicans than Democrats during that time, the paper showed.

47 notes

·

View notes

Video

Childbirth Is Deadlier for Black Families Even When They’re Rich, Expansive Study Finds

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/02/12/upshot/child-maternal-mortality-rich-poor.html

In the United States, the richest mothers and their newborns are the most likely to survive the year after childbirth — except when the family is Black, according to a groundbreaking new study of two million California births. The richest Black mothers and their babies are twice as likely to die as the richest white mothers and their babies.

Research has repeatedly shown that Black mothers and babies have the worst childbirth outcomes in the United States. But this study is novel because it’s the first of its size to show how the risks of childbirth vary by both race and parental income, and how Black families, regardless of their socioeconomic status, are disproportionately affected.

“This is a landmark paper, and what it makes really stark is how we are leaving one group of people way behind,” said Atheendar Venkataramani, a University of Pennsylvania economist who studies racial health disparities and was not involved in the research.

The study, published last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, includes nearly all the infants born to first-time mothers from 2007 to 2016 in California, the state with the most annual births. For the first time, it combines income tax data with birth, death and hospitalization records and demographic data from the Census Bureau and the Social Security Administration, while protecting identities.

That approach also reveals that premature infants born to poor parents are more likely to die than those born into the richest families. Yet there is one group that doesn’t gain the same protection from being rich, the study finds: Black mothers and babies.

Are you a Black parent who recently gave birth? Tell us about it.

“It suggests that the well-documented Black-white gap in infant and maternal health that’s been discussed a lot in recent years is not just explained by differences in economic circumstances,” said Maya Rossin-Slater, an economist studying health policy at Stanford and an author of the study. “It suggests it’s much more structural.”

If anything, the study’s findings understate the dangers of childbirth in much of the United States, a variety of researchers said, because California’s maternal mortality rate has been declining over the last decade, as deaths have gone up in the rest of the country.

Rich Families Have More Premature Babies. But Those Babies Are Less Likely to Die.

Perhaps unexpectedly, babies born to the richest 20 percent of families are the least healthy, the study finds. They are more likely to be born premature and at a low birth weight, two key risk factors for medical complications early in life. This is because their mothers are more likely to be older and to have twins (which are more common with the use of fertility treatments), the researchers found.

But even with those early risk factors, these babies are the most likely to survive both their first month and first year of life.

A similar pattern emerged when it came to the health of the parents themselves: Rich and poor mothers were equally likely to have high-risk pregnancies, but the poor mothers were three times as likely to die — even within the same hospitals. Rich women’s pregnancies “are not only the riskiest, but also the most protected,” the paper’s authors wrote.

A pair of charts showing the relationship between a mother’s income and rates of premature births and infant mortality. The first chart shows that as a woman’s income rises, the likelihood of preterm birth rises. The second chart shows that as a woman’s income rises, rates of infant mortality fall.

This finding suggests that the American medical system has the ability to save many of the lives of babies with early health risks, but that those benefits can be out of reach for low-income families.

Resources outside the medical system also play a role. Separate research on children with leukemia, for example, has found that even when treated at the same hospital and using the same protocol, those from high-income families fared better than those from poorer families.

“It’s not just about the medical care that kids are receiving,” said Anna Aizer, a health economist at Brown University. “There are all sorts of other things that go into having healthy babies. If you’re a higher-income mom who can take time off work, who doesn’t have to worry about paying rent, it’s not surprising you’ll be able to manage any health complications better.”

Money Protects White Mothers and Babies. It Doesn’t Protect Black Ones.

The researchers found that maternal mortality rates were just as high among the highest-income Black women as among low-income white women. Infant mortality rates between the two groups were also similar.

Two charts showing the relationship between a mother’s income and rates of infant mortality by race. The first chart shows that as a Black mother’s income increases, the rate of infant mortality generally drops. The same is true in the second chart for white mothers, but at much lower rates than for Black women.

The richest Black women have infant mortality rates at about the same level as the poorest white women.

The babies born to the richest Black women (the top tenth of earners) tended to have more risk factors, including being born premature or underweight, than those born to the richest white mothers — and more than those born to the poorest white mothers. It’s evidence that the harm to Black mothers and their babies, regardless of socioeconomic status, begins before childbirth.

“As a Black infant, you’re starting off with worse health, even those born into these wealthy families,” said Sarah Miller, a health economist at the University of Michigan. She was an author of the study with Professor Rossin-Slater and Petra Persson of Stanford, Kate Kennedy-Moulton of Columbia, Laura Wherry of N.Y.U. and Gloria Aldana of the Census Bureau.

Black mothers and babies had worse outcomes than those who were Hispanic, Asian or white in all the health measures the researchers looked at: whether babies were born early or underweight; whether mothers had birth-related health problems like eclampsia or sepsis; and whether the babies and mothers died. There was not enough data to look at other populations, including Native Americans, but other research has shown that they face adverse outcomes nearing those of Black women and infants in childbirth.

Charts that show the relationship between a mother’s income by group. The groups are Hispanic mothers and Asian mothers. Generally, rates for Hispanic mothers and Asian mothers track more closely with those of white mothers than Black mothers.

Even before the new paper, research found that Black women with the most resources, as measured by education and class mobility, did not benefit during childbirth the way white women did. The new study demonstrates that disparities are not explained by income, age, marital status or country of birth. Rather, by showing that even rich Black mothers and babies have a disproportionately higher risk of death, the data suggests broader forces at play in the lives of Black mothers, Professor Rossin-Slater said.

“It’s not race, it’s racism,” said Tiffany L. Green, an economist focused on public health and obstetrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The data are quite clear that this isn’t about biology. This is about the environments where we live, where we work, where we play, where we sleep.”

There is clear evidence that Black patients experience racism in health care settings. In childbirth, mothers are treated differently and given different access to interventions. Black infants are more likely to survive if their doctors are Black. The experience of the tennis star Serena Williams — she had a pulmonary embolism after giving birth, yet said health care professionals did not address it at first — drew attention to how not even the most famous and wealthy Black women escape this pattern.

But this data shows how the effects of racism on childbirth start long before people arrive at the hospital, researchers across disciplines say, and continue after they leave. The stress of experiencing racism; air pollution in Black communities; and inequitable access to paid family leave, for example, have all been found to affect the health of mothers and babies.

“Even when it’s not about the direct disrespect that’s going on between the patient and the care provider, there are many ways systemic racism makes its way into the well-being of a pregnant or birthing person,” said Dr. Amanda P. Williams, the clinical innovation adviser at the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative.

California Is a Best-Case Scenario. It Still Lags Behind Other Wealthy Parts of the World.

Many parts of the United States have much higher maternal mortality than California, and fewer policies to support families. California was the first state to offer paid family leave. It has one of the most generous public insurance programs for pregnant women. The state has invested in specific programs aimed at reducing maternal deaths and racial disparities in childbirth.

Yet even in this best-case American scenario, mothers and babies fare worse compared with another rich country the researchers examined: Sweden. At every income level, Swedish women have healthier babies. This held true for the highest-income Swedish women and those from disadvantaged populations, including low-income and immigrant mothers.

A pair of charts showing the relationship between birth outcomes in Sweden and California. The first chart shows that Swedish women have heavier babies at every income level. The second chart shows that Swedish women have lower rates of preterm birth than California women at every income level.

Swedish women have heavier babies at every income level ...

... and far lower instances of preterm birth.

In the United States, earning more regularly translates into superior access to the fastest, most expensive health care. But even with that advantage, the richest white Californians in this study still gave birth to less healthy babies than the richest Swedish women. Their newborns were more likely to be premature or underweight. The two groups had roughly equal maternal death rates.

“That finding really does strongly suggest that it’s something about the care model,” said Dr. Neel Shah, chief medical officer of Maven Clinic for women’s and family health and a visiting scientist at Harvard Medical School. “We have the technology, but the model of prenatal care in the United States hasn’t really gotten an update in the last century.”

A chart showing where the U.S. falls on the spectrum of maternal mortality among peer countries. The U.S. is last in a ranking that includes New Zealand, Norway, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Australia, Britain, Canada and France, in that order.

Paper

Sweden, like most European countries, has universal health insurance with low out-of-pocket costs for the patient. Midwives deliver most babies in Sweden and provide most of the prenatal care, which has been linked to lower C-section rates and lower rates of preterm births and low birth weights. It has long paid leaves and subsidized child care.

Like California, Sweden has also started targeted efforts to reduce maternal deaths. When officials there recognized that African immigrants giving birth were dying more frequently, they began piloting a “culture doula” program, with doulas who were immigrants themselves helping pregnant women navigate the country’s health system.

Local maternal health programs could begin to help reduce racial disparities in the United States, too, as could a more diverse medical workforce, research suggests. Nonprofits and universities have experimented with ways to address racism and poverty, with programs like cash transfers for low-income pregnant women and initiatives to improve the environments of Black communities.

By the time a woman is pregnant, Professor Miller said, “it’s almost too late.”

“Health is going to depend on exposures throughout her life, health care she’s received, environmental factors,” she said. “A lot goes on prior to the pregnancy that affects the health of the mother and baby.”

About the data

The researchers collected birth certificate data for all babies born to first-time mothers in California from 2007 to 2016. The final sample included 1.96 million births. They collected hospitalization and death records for babies for one year from the California Department of Health Care Access and Information, as well as hospitalization records for mothers for nine months before the birth and a year after. They collected maternal death records for the same period from a Social Security Administration data set. They provided birth records to the Census Bureau, which assigned anonymous identification codes to access I.R.S. data and determine new parents’ incomes in the two years before the birth. (Infant mortality records were available only until 2012. Maternal mortality data covers a longer period than in government records, which generally include data for six weeks after a birth, and most likely capture some deaths unrelated to childbirth.)

In Sweden, the researchers collected similar health and mortality data from the National Board of Health and Welfare. The final sample included 463,865 births. Analogous maternal morbidity data was unavailable. They linked babies to their parents and collected parents’ demographic and financial data from Statistics Sweden. Sweden has a smaller gap between the highest and lowest earners than the United States.

#tiktok#article#new york times#Healthcare#Health Care#infant mortality#california#reproductive justice#reproductive freedom#reproductive rights#reproductive choice#reproductive health#health news#medical studies

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Sharon Parrott

It’s tempting to ignore a budget resolution released just days before the start of the fiscal year that it’s meant to guide, and amid the chaotic debate around a short-term extension of government funding to avoid a shutdown. But House Budget Committee Chair Jodey Arrington’s proposed budget is important for what it illustrates about House Republicans’ disturbing vision for the country: health care stripped away from millions of people, higher poverty and hunger, capitulation to climate change, more tax cheating by high-income people, and large-scale disinvestment from the building blocks of opportunity and economic growth—from medical research to education to child care. It would narrow opportunity, worsen racial inequities, and make it harder for people to afford the basics. It reflects the wrong priorities for the country and should be roundly rejected.

Chair Arrington made clear in his remarks the intent to extend the expiring tax cuts from the 2017 tax law, which included large tax cuts for the wealthy. In addition, the budget resolution itself would pave the way for unlimited, unpaid-for tax cuts that could go well beyond those extensions. The extensions alone would give annual tax breaks averaging $41,000 to tax filers in the top 1 percent and cost more than $350 billion a year, the Congressional Budget Office estimates. The budget reflects none of these costs and fails to explain how—or whether—they will be offset.

A shocking share of the spending cuts Chair Arrington specifies target people with low and moderate incomes, including $1.9 trillion in Medicaid cuts and hundreds of billions in cuts to economic security programs, such as cuts to assistance that helps people afford food and other basic needs. Just last week the Census Bureau released data showing that poverty spiked last year, more than doubling for children. Rather than proposing policies that could reverse this deeply troubling trend, the budget proposal would deepen poverty and increase hardship.

The budget would also make deep cuts in the part of the budget that is funded annually through appropriations bills. Disingenuously, the budget resolution shows that these cuts total more than $4 trillion over ten years—but hides the program areas that would be cut, labeling them “government-wide savings.” But this year’s House Appropriations bills—which include substantial cuts—make clear that cuts would fall on a wide range of basic functions and services that support families, communities, and the broader economy, including Social Security customer service, support for K-12 and college education, funding for national parks and clean air and water, rental housing assistance for families with low incomes, and more.

Chair Arrington claims the budget’s deep and damaging program cuts are in the name of deficit reduction. But the failure to identify a single revenue increase for high-income people or corporations—and in fact, to potentially shower them with more unpaid-for tax cuts—is an extreme and misguided approach. Moreover, calling for a balanced budget in ten years is merely a slogan that has little to do with addressing our nation’s needs—and the budget resolution resorts to gimmicks and games to even appear to get there, including $3 trillion in deficit reduction it claims would accrue from higher economic growth it assumes would be achieved by budget policies.

A budget plan should focus on the nation’s needs and lay out an agenda that broadens opportunity, invests in people and families, reduces the too-high levels of hardship and financial stress faced by households across the country, and raises revenues for those investments. But the Arrington budget blueprint would shortchange much-needed investments and lock in wasteful tax cuts to the already wealthy for the next decade.

House Republicans are pursuing a damaging agenda at every turn—first threatening the nation with default, and now demanding deep cuts in an array of priorities in this year’s appropriations debate, risking a government shutdown, and proposing a budget blueprint that would take the country in the wrong direction.

#us politics#news#common dreams#2023#republicans#conservatives#rep. Jodey Arrington#house budget committee#house republicans#us house of representatives#federal budget#trump tax cuts#trump 2017 tax cuts#congressional budget office#Medicaid cuts#social security cuts#House Appropriations committee#federal deficit#op eds#Sharon Parrott

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently, “national statistics tell us that over 60,000 Black women are missing, and Black women are twice as likely than they appear to be victims of homicide,” - Brittney Lewis

Minnesota state lawmakers are moving forward with a bill that would establish the nation’s first office to investigate cases of missing Black women and girls as tens of thousands of women of color remain missing in the U.S.

On Feb. 20, the Minnesota House voted 110-19 in favor of advancing House Bill HF55. “And it is on the fast track this year to be signed into law,” Rep. Ruth Richardson, DFL (Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party), the bill’s author, told Yahoo News. “This is part of the governor's budget, and it's one of his top priorities. So we are excited to be at a point where we can finally get this across the finish line.”

In previous years, similar bills passed in the Minnesota House but failed in the Senate. If the legislation is signed into law it would require the Bureau of Criminal Apprenticeship to operate a missing person alert program for Black women and girls.

The Office of Missing and Murdered Black Women and Girls would review missing persons and cold cases, and the first-of-its-kind project is expected to cost roughly $2.5 million.

In the United States, Black women only make up 13% of the female population but studies found that they make up 35% percent of missing women in the country. In 2020, during the pandemic, nearly 100,000 of the 250,000 women that went missing in the U.S were women of color.

Currently, “national statistics tell us that over 60,000 Black women are missing, and Black women are twice as likely than they appear to be victims of homicide,” Brittney Lewis, co-founder of Research in Action, told Yahoo News. “In the state of Minnesota, Black women are three times more likely to be murdered than white women in Minnesota.”

According to the state report completed by Minnesota’s Missing and Murdered Black Women and Girls Task Force, created in 2021, Black women are less likely to receive media attention when they go missing.

“What we’re finding is that people are disappearing for a number of reasons: sex trafficking of our young girls, increase in domestic violence, mental health reasons, and there are a lot of systemic reasons,” Natalie Wilson, co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation, a nonprofit organization that brings awareness to missing people of color, told Yahoo News.

Wilson says she is working to bridge the gap so that all missing women have the same media attention and resources. “We’re trying to eliminate this barrier because what we’re finding oftentimes with our communities [is that] race, zip code, where you live, education, your economic status — all of these things are barriers,” Wilson said.

In 2016, when 21-year-old Keeshae Jacobs went missing in Richmond, Va., her mother said she faced barriers that made her feel like she was the only one searching for her child.

“Sometimes I feel like I'm the only one fighting here,” Toni Jacobs, Keeshae’s mother, told Yahoo News. “When I went to go file the police report that she was missing, it felt like the police officer didn’t believe me.”

“

People [said] ‘oh she had a boyfriend. She just ran out. She was pregnant and she was scared to tell me.’ I mean, these are the first things that come to my mind and I’m like this is not fair,” Jacobs said.

According to experts, cases that involve missing Black women and girls stay open four times as long compared to other cases involving white people.

“People are taking them because they know they’re not getting attention,” Jacobs said. “I shouldn't have to wait six years and I honestly believe I’m fighting by myself to bring my daughter home.”

In 2014, 8-year-old Relisha Rudd went missing in Washington, D.C, and still has not been found.

“If a white girl with blond hair and blue eyes goes missing every light comes on. [But] when a black girl or black woman goes missing you never hear about it,” Dr. Verna Price, founder of Girls Taking Action, a nonprofit organization in Minnesota that mentors young girls, told Yahoo News.

Experts say this is known as “‘missing white woman syndrome” — a term that refers to the unequal amount of coverage that white women receive compared to women of color.

In 2021, MSNBC host Joy Reid called the coverage of Gabby Petito a prime example of missing White woman syndrome. “Why not the same media attention when people of color go missing?” Reid asked.

According to Lynnette Grey Bull, founder of Not Our Native Daughters, “White people were more likely to have an article written while they were still missing,” she said on MSNBC.

Price says this is not just a problem in Minnesota as Black women and girls have been targeted nationwide.

“In this country, Black women since slavery have been dispensable and it is high time that we protect us,” Price said.

Richardson and supporters of the legislation said they are hopeful that the bill will pass and spur other states to take action on the issue.

“We believe that this is a blueprint for a national response,” Richardson said. “We are hoping that we can help to lead the way to ensure that Black women and girls are extended the same protection and the same support and the same energy that we see in coverage of other cases.”

By

Jayla Whitfield-Anderson

#Not Our Native Daughters#USA#minnesota#Research In Action#House Bill HF55#The Office of Missing and Murdered Black Women and Girls#Minnesota’s Missing and Murdered Black Women and Girls Task Force#Girls Taking Action#Black and Missing Foundation

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...] Most aspects of life in 1870 (except for the rich) were dark, dangerous, and involved backbreaking work. There was no electricity in 1870. The insides of dwelling units were not only dark but also smoky, due to residue and air pollution from candles and oil lamps. The enclosed iron stove had only recently been invented and much cooking was still done on the open hearth. Only the proximity of the hearth or stove was warm; bedrooms were unheated and family members carried warm bricks with them to bed.

But the biggest inconvenience was the lack of running water. Every drop of water for laundry, cooking, and indoor chamber pots had to be hauled in by the housewife, and wastewater hauled out. The average North Carolina housewife in 1885 had to walk 148 miles per year while carrying 35 tons of water. Coal or wood for open-hearth fires had to be carried in and ashes had to be collected and carried out. There was no more important event that liberated women than the invention of running water and indoor plumbing, which happened in urban America between 1890 and 1930.

IS U.S. ECONOMIC GROWTH OVER? FALTERING INNOVATION CONFRONTS THE SIX HEADWINDS by Robert J. Gordon (NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH)

7 notes

·

View notes

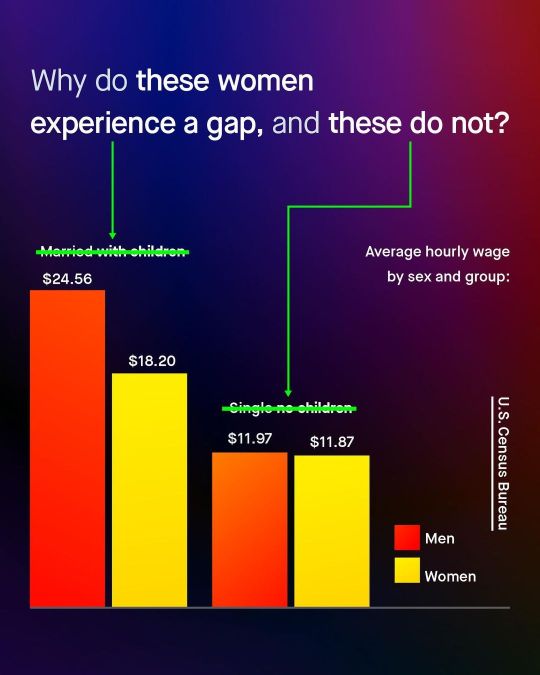

Text

Unsurprisingly, I see a lot of conversation about the infamous ‘gender pay gap’.

A lot of opinions, and strongly held believes, and plenty of information that is not accurate, or at least… not anymore.

For the nature and shape of the pay gap has changed. And so out of the outrage, garbled conjecture, and political agendas; must come a new conversation that once again asks, ‘why are women paid less?’

Because the truth is, it’s not ‘women’ who are getting paid less, but rather ‘women with children’.

Mothers who are out of work, either full or part time, whose lower income drags the average down - they are a large piece of the conversation, too often missing.

No. Women are not paid less than men, and such slogans belong in the museum, not upon the placards of today.

Now it’s time to talk about parenthood.

To honestly discuss why mothers are paid less than fathers, and ask if this is a result of societal expectations… or women’s own free choices?

Do women want to be part time parents?

Do men? Who wants to work full time at a job they don’t even like anyway?

Do you?

We rightly talk about the price of motherhood on women; but what is the price of barely seeing your child at all?

What is the price of the late nights at work, or early morning shifts; or the second job, to make ends meet?

Also if mothers are to get equal pay, are they willing to share their parental leave with fathers in order to get it?

These are better questions.

And one’s I don’t see asked.

Instead I find the pay gap conversation to be a broken record; that redirects energy from logic and reason, into outrage and anger instead.

Yet another stick to hit ‘men’ with, another patriarchal poster child, and sermon preached from the pulpit.

It is a gap that is never closed, because it is never truly discussed.

So tell me, what’s in the gap?

--

Sources:

The Economist, Motherhood Penalty:

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/01/28/how-big-is-the-wage-penalty-for-mothers

US Census Bureau:

https://towardsdatascience.com/is-the-difference-in-work-hours-the-real-reason-for-the-gender-wage-gap-interactive-infographic-6051dff3a041?gi=2dc24b441466

Denmark Study:

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.20180010

The Pay Gap Explained, full video:

https://youtu.be/hP8dLUxBfsU

==

What's in the gap is different choices and different priorities. It's sexist to act like men's choices are the default, correct ones, and if men and women make different choices and get different outcomes, there's a problem that needs to be solved.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18179326/

Abstract

Previous research suggested that sex differences in personality traits are larger in prosperous, healthy, and egalitarian cultures in which women have more opportunities equal with those of men. In this article, the authors report cross-cultural findings in which this unintuitive result was replicated across samples from 55 nations (N = 17,637). On responses to the Big Five Inventory, women reported higher levels of neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness than did men across most nations. These findings converge with previous studies in which different Big Five measures and more limited samples of nations were used. Overall, higher levels of human development--including long and healthy life, equal access to knowledge and education, and economic wealth--were the main nation-level predictors of larger sex differences in personality. Changes in men's personality traits appeared to be the primary cause of sex difference variation across cultures. It is proposed that heightened levels of sexual dimorphism result from personality traits of men and women being less constrained and more able to naturally diverge in developed nations. In less fortunate social and economic conditions, innate personality differences between men and women may be attenuated.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27000535/

Abstract

Men's and women's personalities appear to differ in several respects. Social role theories of development assume gender differences result primarily from perceived gender roles, gender socialization and sociostructural power differentials. As a consequence, social role theorists expect gender differences in personality to be smaller in cultures with more gender egalitarianism. Several large cross-cultural studies have generated sufficient data for evaluating these global personality predictions. Empirically, evidence suggests gender differences in most aspects of personality-Big Five traits, Dark Triad traits, self-esteem, subjective well-being, depression and values-are conspicuously larger in cultures with more egalitarian gender roles, gender socialization and sociopolitical gender equity. Similar patterns are evident when examining objectively measured attributes such as tested cognitive abilities and physical traits such as height and blood pressure. Social role theory appears inadequate for explaining some of the observed cultural variations in men's and women's personalities. Evolutionary theories regarding ecologically-evoked gender differences are described that may prove more useful in explaining global variation in human personality.

#The Tin Men#pay gap#pay gap myth#sex differences#earnings gap#motherhood#priorities#maternal instinct#myths that need to die#gender pay gap#feminist lies#religion is a mental illness

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This political cartoon by Louis Dalrymple appeared in Judge magazine in 1903. It depicts European immigrants as rats. Nativism and anti-immigration have a long and sordid history in the United States

* * * * *

How foreign immigrants support the US economy

During my meetings with readers across the nation, the issue of immigration is frequently raised as a concern. It was a topic of conversation in my meeting on Saturday with readers in San Antonio. (See photo below.) After I made my usual remarks about why foreign immigration is good for the US, a reader suggested that I include the facts in my newsletter. So, here they are:

According to recent reports by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, foreign immigrants have fueled the better-than-expected performance of the US economy over the last decade. See Forbes, How Immigrants Are Boosting U.S. Economic And Job Growth. As summarized in the Forbes article,

In 2023, “foreign-born” workers comprised nearly 19% of the U.S. labor force . . . This is an uptick from 15.3% in 2006.

Immigrants have contributed largely to consumer spending growth by about 0.2 percentage point last year, with a similar boost expected this year, along with an increase in gross domestic product—a measure of all the goods and services produced—by 0.1 percentage point per year since 2022 . . . .

Federal Reserve Bank chair Jerome Powell [said], [I] t's just reporting the facts to say that immigration and labor force participation both contributed to the very strong economic output growth that we had last year.”

Immigration is fueling business and job creation in the U.S. According to MIT research, immigrants are 80% more likely to start a business than native-born U.S. citizens. They are also responsible for 42% more job creation than native-born founders.

So, larger-than-expected foreign immigration has increased consumer spending, GDP, start-up ventures, and job creation. That’s all good.

And there is a downside to restricting foreign immigration:

The U.S. needs more workers to keep the economy humming. In the absence of foreign-born labor, the U.S. talent pool will continue to decline because of lower birth rates with an accompanying aging workforce of Baby Boomers looking to retire.

Indeed, according to a US Census Bureau report, the US population would decrease (to 319 million) instead of growing (to 404 million) by 2060 if the US cut-off immigration. Under a “zero immigration” policy, the percentage of the population over 65 would increase from 15% in 2024 to 26% in 2060—not a good trend. In its starkest terms, immigration is necessary to guarantee a robust, growing labor force to drive the largest economy in the world.

But there’s more. Over the last decade, foreign immigration has saved nine US states from an absolute decline in population. The NYTimes reported on the findings of the 2020 Census in an article entitled, Why Your State Is Growing or Stalling or Shrinking.

Even with foreign immigration, four states lost population overall, including West Virginia and Illinois. Moreover, foreign immigration saved nine additional states from a shrinking population base—including Mississippi, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

The debate about population growth is complicated. But in the short term, unplanned depopulation is devastating to economies and communities. To see the effects of a shrinking population and dwindling labor force, we need only look at many communities across America where young families are moving out, retirees are aging in place, and restrictive immigration policies discourage foreign immigrants from entering the workforce.

Conversely, states on the “front line” of foreign immigration into the US have booming economies—including California, Texas, Arizona, and Florida.

This interactive map will allow you to compare the economic impact of immigration on the respective states. As a point of comparison, California is the fifth largest economy in the world. 26% of its population consists of foreign immigrants, who contribute $137 billion in annual taxes, control $351 billion in spending power, and include 780,000 entrepreneurs. West Virginia’s population is 1.6% foreign immigrants who contribute $324 million in taxes and control $880 million in spending power. There are no recorded immigrant entrepreneurs in West Virginia.

Check out your own state on the interactive map.

Is our immigration system broken? Absolutely! But let’s not conflate the broken immigration system with the fact that America is strong (in part) because of immigration and will remain strong (in part) because of immigration. Foreign immigrants make America a better, more productive, and more innovative nation. Let’s not lose sight of that truth in the debate over how we allow foreign immigrants to enter the US.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

3 notes

·

View notes