#grassland amphibians

Photo

The Smooth Newt with the Smooth Moves

Also known as the European newt, northern smooth newt, or common newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), the smooth newt is one of the most common species in Europe and western Asia. It is also the only newt species found in Ireland. There are currently three recognised subspecies distributed throughout this range, and four others have been reclassified as distinct species. The common newt is able to survive in a variety of habitats, including deciduous and coniferous forests, wetlands, meadows, parks, and gardens. Their only requirements are sufficient sunlight and water with sufficient vegetation.

Like most newts, the northern smooth newt spends the majority of its time foraging for food on land. Their diet is carnivorous, consisting of insects, worms, snails, slugs, and larvae. When available, L. vulgaris may also eat the eggs of its own species. In turn, many animals prey on the European newt, including waterbirds, snakes, frogs, and larger newts. To avoid these predators the smooth newt is active mainly at night, and will secrete a toxic mucus when threatened. While active, they are largely solitary but from October to March several individuals will hibernate together under logs or leaf litter burrows.

Almost as soon as the common newt emerges from hibernation, they begin migration to their breeding sites-- usually the ponds in which they spawned. Males undergo a dramatic transformation, growing large crests and becoming brightly colored. When a female enters the water, the male swims around her and sniffs her cloaca. He then vibrates his tail to fan his pheromones towards her. Finally, he will swim away and, if the female is interested, she will follow him. He then deposits a packet of sperm, or spermatophore, that the female picks up for fertilization. Rival males may try to lead the female towards their own spermatophores, and clutches of eggs often have multiple fathers.

Females deposit anywhere from 100 to 500 eggs, each of which is carefully wrapped in aquatic vegetation. Larvae hatch after only 20 days, and quickly begin developing. Unlike frogs and toads, newt larvae have external, feathery gills, and develop their front legs first. After about three months, the larvae absorb their gills and leave the water as newtlets or efts. However, when temperatures are particularly low and aquatic prey is abundant, some adults retain their gills and stay aquatic in a phenomenon known as paedomorphism. These adults are fully capable of sexual reproduction, and when moved to areas with a larger population will often metamorphose into terrestrial adults.

Adult smooth newts are rather small, reaching only 9–11 cm (3.5–4.3 in) and 0.3–5.2 g (0.011–0.183 oz). Males are slightly larger than females. The head and back are dark brown or olive, while the underside is much lighter. Both males and females have dark spots on their bellies, and males also sport a bright orange stripe. In the spring, the colors in males become more vivid and the spots grow larger. Males also develop a large yellow crest that runs from the head to the table, and is dotted with dark bands.

Conservation status: The IUCN has designated the European newt as Least Concern, as it is common over most of its range. Threats include habitat destruction and the introduction of invasive fish species.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Philip Precey

Derek Middleton

Christoph Moning via iNaturalist

Kristýna Coufalová via iNaturalist

#common newt#smooth newt#Urodela#Salamandridae#newts#salamanders#amphibians#deciduous forests#deciduous forest amphibians#evergreen forests#evergreen forest amphibians#grassland birds#grassland amphibians#wetlands#wetland amphibians#urban fauna#urban amphibians#europe#asia#west asia#animal facts#biology#zoology

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

you have everything you need to survive and you will get through the trip and come home safely

for the purposes of "polls can only have ten things", your options are limited to land ecosystems

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Earth Day!

We share this beautiful planet with over two million other species, from wasps the size of a grain of dust to whales larger than an office building. Yet, many of these species now face extinction due to the ways in which we humans have modified the planet to suit our needs. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 13% of birds, 21% of reptiles, 27% of mammals, 37% of sharks, and 41% of amphibians are currently endangered, and some estimates suggest that 28% of all species on Earth are at risk of extinction in the near future. Imagine you woke up tomorrow and more than a quarter of every plant, animal, and fungus, from the elephants at the zoo to the earthworms beneath the soil, simply vanished, never to be seen ever again. If we choose to continue treating our planet so poorly, this will become a reality.

Here at Consider Nature, we believe the best way to protect our planet is to arm ourselves with knowledge! Over the years, we have written many articles on some of Earth’s coolest, weirdest, and most-endangered species, in the hope of inspiring readers to step up to the plate and protect biodiversity. I hope you will spend a few minutes of your Earth Day today reading about some of the species we believe are worth saving.

Zacaton grasslands in central Mexico, home to the Zacatuche, or volcano rabbit. Image credit: Jurgen Hoth

The Succulent Karoo, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth and home to the Karoo Padloper. Image credit: Tjeerd Wiersma under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The Gulf of California, home of the critically endangered Vaquita. Image credit: Natural World Heritage Sites.

659 notes

·

View notes

Text

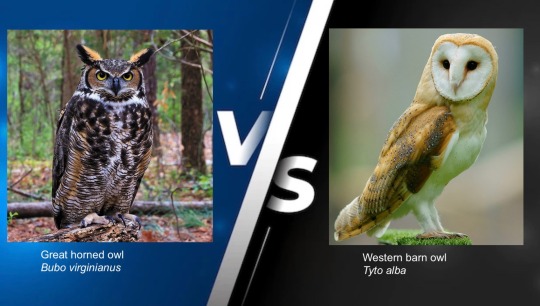

Two popular classics! But who is the Superb Owl?

The most widely distributed owl in the Americas, the great horned owl ranges throughout North America and much of Central and South America. They can be found in almost any habitat. These owls mostly prey on rodents and lagomorphs, but are opportunistic hunters and will take anything they can catch, including smaller owls. They hunt by watching from a perch. Regarding their ecological niche, they are sometimes described as the nocturnal equivalent of red-tailed hawks. Great horned owls nest earlier in the year than most other raptors. These owls are very long-lived, with a typical lifespan of around 13 years in the wild (with a record of 28) and up to 50 in captivity!

Western barn owls live throughout Europe as well as much of Africa and the Arabian peninsula in a wide variety of habitats, but most especially favoring open woodland and grasslands. These owls mostly eat small mammals such as rodents and shrews, but will also eat birds, amphibians, lizards, and insects. They hunt by flying slowly over ground and pouncing when movement is detected. Western barn owls are usually monogamous, mating for life. After fledging, young remain with their parents for only about a month. Since barn owls have relatively high metabolic rates, they eat proportionally more rodents than other owls and are thereby appreciated by farmers as effective pest control.

509 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conserving and Restoring North American Prairie

Home to hundreds of species of birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and pollinators, grasslands are unsung heroes. Alongside providing a haven for wildlife, this iconic landscape sequesters carbon, reduces soil erosion, ensures clean water, protects biodiversity, and more.

You might be asking yourself how we could live without the countless benefits grasslands provide us and wildlife, and the answer is - we probably wouldn’t be able to for very long.

We have lost more than 50 million acres of the landscape in the last 10 years due to climate change, agricultural conversion, invasive species, and other threats. This map can help guide voluntary conservation in this critical landscape - help us help each other keep the green areas green and restore the yellow and purple areas.

Learn more: http://ow.ly/nHQ550M4GJL

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

A writer’s guide to forests: from the poles to the tropics, part 7

Is it no.7 already? Wow. A big shout out to everyone who has had the patients to stick with this. Now onto this week’s forest…

Dry forest

Water is life. That’s a fact. And especially where it doesn’t rain for more than half the year.

Location: Dry forests are scattered throughout the Yucatán peninsula ,South America, various Pacific islands,Australia, Madagascar, and India. Areas have been cleared by human activity, and the SA dry forests are classified as the most threatened tropical forests.

Climate: Temperate to tropical, with just enough rain to sustain trees. Many are monsoonal, with rain coming in one or two brief periods separated by a long dry season.

Plant life- Hardy trees, such as Baobab and Eucalyptus are able to last with little rain by tapping into groundwater with extensive root systems. Many trees are evergreen, but in India, many species are deciduous. Trees are often more spaced out, and shrubs and grasses grow extensively. Cacti are common plants in the Americas, with some growing tall enough to be considered trees. In order to survive the heat and lack of water, many small plants are annuals, or store water in tubers. Palms can make up a large percentage of the trees, as was the case in the now vanished forests of Easter Island.

Animal life- As they can come and go when they please, birds are common species. Larger animals are active year round, with smaller species of mammals, amphibians, and certain insects only coming out during the rainy season. Isolation means that islands become home to many endemic species; think about Madagascar and the lemurs, or Darwin’s finches, iguanas, and tortoises in the Galapagos. Isolation has also led to the marsupials of Australia developing to fill the niches that would normally be occupied by placental mammals .The introduction of invasive species has brought about the extinction of island fauna.

How the forest affects the story- Water, or the lack of will be the biggest challenge your characters will face. Rivers and lakes may be seasonal, so other sources will have to be utilized. Drinkable fluids can be obtained from various plants and animals, or maybe the bedrock is porous and water accumulates in cenotes. Your characters could come from a culture that builds artificial reservoirs to collect the rain and store it for the dry season. With careful water management, cities can thrive in dry areas. But your characters will have to be careful. Prolonged drought will see societies go the way of the Maya. Deforestation leaves the topsoil vulnerable to the wind, and forests, farms, and grassland will inevitably turn to desert. Whether nomadic or sedentary, your characters and their society will have to find a way to interact with the forest without destroying it or themselves. Can they do it? Can a damaged biosphere be restored before it’s too late? The success or failure of your characters and/or their predecessors can be a driving focus of the plot. Of course ,when the rains do come, it could be in the form of a cyclone. Dry ground does not readily absorb water, and flash floods are a danger. Water can grant life, but it can take it as well.

#writing#creative writing#writing guide#writing inspiration#writing prompts#writer#writers#writing community#writer on tumblr#writeblr

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plains Bison in Custer, South Dakota, USA

Stephanie LeBlanc

The Plains bison is one of two subspecies/ecotypes of the American bison, the other being the wood bison.

Status: Near Threatened

Population: 45,000

Scientific Name: Bison bison bison

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Mammalia

Order: Artiodactyla

Family: Bovidae

Subfmaily: Bovinae

Tribe: Bovini

Genus: Bison

Weight: 701 to 2,000 pounds

Length: 7-12 ft.

Habitat: Grassland

Range: Bison once roamed from Florida to Washington, Canada, and Mexico - The entire U.S.

Predators: Wolves are the primary predator of bison across the continent. Local knowledge also indicates that bears play a role in predation.

Diet: Bison are considered generalist foragers, meaning they eat a wide array of herbaceous grasses and sedges commonly found in mixed-grassed prairies. These types of plants include species such as Blue gramma, sand dropseed, and little bluestem.

Lifespan: The average lifespan for a bison is 10–20 years, but some live to be older. Cows begin breeding at the age of two and only have one baby at a time. For males, the prime breeding age is six to 10 years.

Importance: Bison graze the grasses at different heights, providing nesting grounds for birds. They also roll around and pack down the soil in depressions in the ground known as wallows. Their wallows fill with rainwater and offer breeding pools for amphibians and sources of drinking water for wildlife across the landscape.

#Custer#South Dakota#USA#Plains Bison#Bison#Wildlife#SDWildlife#US#United States#United States of America#North America

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

High above the cloud forest tree line you can still find frogs on the Peruvian Andes, like this amazing Abra Acanacu marsupial frog (Gastrotheca excubitor). They live in the puna grasslands ecosystem with mosses, grasses and small shrubs and evolved to entirely skip the tadpole stage, keeping their eggs in their back pouch until tiny replicas of them will eventually emerge. Chytrid fungus stroke hard on them and they’re presently listed as Vulnerable by IUCN. The second photo, while not “in situ”, is nonetheless important to me cause it’s the last living individual. Afterwards I only found dead ones killed by the fungus. #gastrotheca #amphibian #conservation #peru @conservacionamazonica @ilcp_photographers https://www.instagram.com/p/CktSK7tqXzJ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

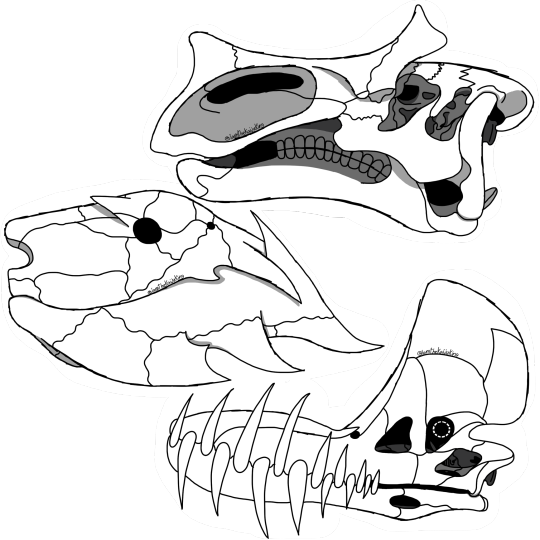

Skulls of some critters from @bogbiter’s Awakened: Bleeding Realm

To quote him

“Top right is a thundered, aka Okpesaurus. Massive hadrosaurs that migrated down into South America, where they adapted to mountainous grasslands. They would travel back up into the americas around the 1200s, seemingly with little competition from mastodons and ground sloths.”

“The second is the Slide-Rock Bolter, a massive amphibian that resembles a frog, though studded with osteoderms and being larger than a rhino. They hunt the mountains and will use their armored body to slide down slopes to get from point a to b, or to crash into rivals or herds down beloe.”

“Third is the Southern Stormwing, the largest flying wyvern in the world. Though in decline due to overfishing, they also make do by the hunting of marine mammals, birds, fish, squid, and small mosasaurs. Their impressive crest in life is covered in semi-fleshy "spines", that help communicate health to other individuals.”

#skulls#speculative ecology#speculative biology#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#speculative anatomy#sketches#bogbiter#awakened: bleeding realm

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

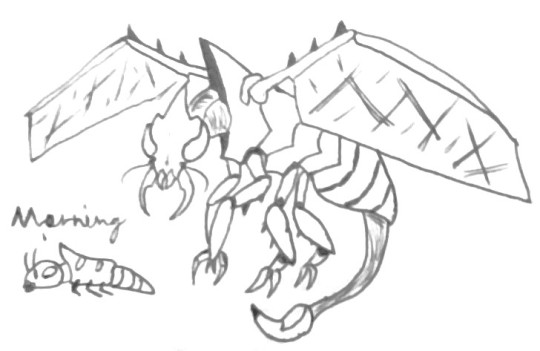

Another neopteran, this time based on potter wasps

-

WYRADIAL

Title - Frigid insect

Monster class - Neopteran

Known locales - Deserts and savannah

Element/ailment - Mucus + Ice

Elemental weakness - Fire (3), Water (2), Thunder (1), Ice (1), Dragon (0)

Ailment weakness - Poison (3), Paralysis (3), Blast (2), Stun (1), Sleep (0)

Wyradial is a neopteran that inhabits desert regions, usually nesting close to grassland or oases. It is distinguished by its wasp-like appearance, with long sharp wings and a flexible stinger, and the dashing blue-and-yellow colouring of its exoskeleton. Its limbs are well-suited for handling debris, useful for building its caches, whilst the cutting mandibles hide a gland that excretes a thick mucus at surprising pressure.

Wyradial's offspring are called Neoradials. In their larval state, they are mellow and slow in comparison to the high-octane adult. Lacking the developed features and ailments of Wyradial, Neoradials defend themselves by spitting a strong silk, encasing attackers in webbing to buy themselves time to dig to safety.

An omnivore, there is nothing Wyradial won't gather in its single-minded pursuit of preparing for the future. Carrion, fruit, plants, tubers, fungi, bone, minerals - anything edible is collected by the neopteran and stored in the large caches it creates out of rock, mud and wood. Small burrows close to the cache host Wyradial's offspring, the Neoradials. These caches are vital for the neopteran and its brood to survive harsh dry seasons, and Wyradial will viciously defend them. Field workers are advised to steer clear of the cache; Wyradial will not hesitate to attack what it perceives to be a potential thief. Only when the neopteran is out foraging is it relatively docile, if only because it is too occupied with its work to bother with humans.

The strong mucus Wyradial uses to craft its structures is also an effective defensive weapon, spat out onto foes to slow their movements and potentially let objects in the environment stick to them. If this fails, the neopteran brings its flexible stinger to bear and launches an icy residue. This can either be hardened on the stinger and shot as a bullet-like structure, or sprayed out in a mist that hardens on contact (incidentally, this icy residue is used to keep its cache cool, allowing it supplies to last for longer). Otherwise, Wyradial makes use of its flight to attack in hit-and-run styles, lashing out with its limbs and stinger.

Predictably, creating a large cache loaded with food can attract enemies. The Neoradials are the first line of defence, keeping watch from their burrows and mobbing potential thieves with strands of webbing. Should this fail, they release pheromones that triggers a defensive response from any Wyradial close at hand. In addition, Wyradials tend to gather in groups; one can expect four or five adults within the same territory. They must be careful not to converge too closely, though, lest too many opportunists be drawn to the gathering.

While not a particularly challenging monster (Low Rank - 1, High/Master Rank - 1), Wyradial nevertheless tests a hunter's skill with its speed and projectile attacks. Hunters should aim for the wings and its stinger, which can help disable its best options. Remove mucus as soon as possible, as Wyradial's icy residue will adhere tightly to it and heighten the chilling effect.

Wyradials are threatened by a number of monsters; the amphibian Serencabra feeds on Neoradials, and may even kill an adult if it can. Even worse, the carapaceon Emverion is Wyradial's nemesis, dedicated to raiding its stores and taking all the neopteran's hard-earned food for itself. Only by working with others of their kind can Wyradial overcome these challenges.

-

Thank you for reading and take care.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 16th, 2023

Chinese Mantis (Tenodera sinensis)

Distribution: Native to China, Japan, Korea, Micronesia and Thailand. Found throughout eastern North America, plus scattered areas in the west.

Habitat: Usually found on tall plants or grasses, especially on areas with a view. Found around houses, grasslands, pastures, agricultural and open areas.

Diet: Carnivorous generalists; feed mainly on other insects and spiders, such as hornets, grasshoppers, butterflies and katydids, but have also been seen consuming small reptiles, amphibians and hummingbirds (though this is likely an uncommon occurence!).

Description: These large mantises were introduced to North America in the 1890s, and have since become well-established throughout the eastern half of the continent. Despite being a non-native species, the Chinese mantis is sometimes deliberately released into gardens as a method of biological pest control, which isn't a very good idea. While they do consume undesirable species, they're also indiscriminate eaters which also eat beneficial insects, like pollinators. Their over-abundance and general success has come at the cost of other native mantis species, whose populations have been declining throughout North America.

Because of its particular style of hunting, standing very still before swiping out at its prey when it draws near, two separate unrelated martial art styles have been developed based on the Chinese mantis: the praying mantis kung fu, developed in eastern China in the mid-1600s, and the southern praying mantis kung fu, developped by the Hakka people of southern China.

(Images by Dave Parker and Luc Viatour)

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Call the Common Midwife Toad

The common midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) is one member of the genus Alytes, which consists of five species total and is known collectively as midwife toads. These species can be found throughout most of Europe and northern Africa; the common midwife toad resides primarily in the Iberian Peninsula, in a wide range of habitats including temperate forests, grasslands, and agricultural areas. During the day they can often be found under logs, in crevices, or hiding in the burrows of other animals and at night they emerge to forage for food. In the winter

Like most anurans, A. obstetricans eats mainly small arthropods like beetles, spiders, and maggots. The tadpoles are solely herbivorous and feed on algae and plant debris. Predators of the common midwife toad include snakes and larger birds like herons. However, this species has a range of defenses against such predators. When threatened individuals inflate themselves with air and rears up on all fours to make themselves appear bigger. They also secrete a foul smelling toxin from the warts on their back; this toxin is potent enough to kill a venomous adder snake (Vipera berus) within hours. Given this risk, adults are rarely preyed upon, but tadpoles lack this toxin and are more often consumed by fish and aquatic insects.

Midwife toads, including the common midwife toad, get their name from their distinct mode of reproduction. The breeding season occurs from spring to summer. Large males emit a high pitched “beeping” call to attract females. When a female selects a suitable mate, he clamors onto her back and grasps her tightly. By squeezing her sides, the male induces the female to eject a mass of up to 150 eggs in a jelly-like mass. Then the male uses his toes to tease the mass apart into strings which he then threads around his hind legs. The female’s contribution is over, but the male will carry this cargo with him for 3-6 weeks, keeping them moist by periodically soaking in freshwater and protecting them from potential predators. Once the eggs hatch into a body of water, tadpoles take several months to reach their adult form. Young then take another 2-3 years to become sexually mature, and can live as long as 8 years.

Despite their name, common midwife toads are not true toads, though they share many similar characteristics. Their skin is thick and warty, and the body is short and stubby. They also lack webbing between their toes, as they are a largely terrestrial species. These toads are small, growing no longer than 6 cm long and weighing less than 10g. Females are generally larger than males. The color of the common midwife toad ranges from gray to cream to brown, with darker spots along the head and back.

Conservation status: The common midwife toad is considered Least Concern by the IUCN, due to their large population size. However, populations have been declining due to habitat fragmentation and loss, as well as epidemics of the highly deadly chytrid fungus.

Photos

Ronald Altig

Frank Vassen

Daniele Seglie (via iNaturalist)

Gernot Kunz (via iNaturalist)

#common midwife toad#anura#Alytidae#midwife toads#frogs#amphibians#deciduous forests#deciduous forest amphibians#grasslands#grassland amphibians#urban fauna#urban amphibians#europe#western europe#animal facts#biology#zoology

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was researching stuff and encountered a wild suggestion from the major English-language search engine:

“Do hummingbirds live in the Andes?”

Hummingbirds are only found in the Western Hemisphere. Put another way: Hummingbirds only live in “the Americas.”

Depending on who you ask, there are between 325-ish and 360-ish unique species of hummingbird (in formal taxonomy, this includes the birds in the hummingbird family, Trochilidae).

Of those hundreds of hummingbirds, only about a dozen or so live north of Mexico, mostly in Texas and the Southwest. But those other hundreds of hummingbirds? Farther south. And so hummingbirds are closely associated specifically with Latin America.

The highest local (”hotspot”) biodiversity of mammals, birds, amphibians, and plants on the planet all occurs in the tropical Andes (specifically, within Ecuador and Colombia). The tropical Andes mountains feature extreme elevation changes in small areas (they’re very steep), which means the temperature situation changes rapidly in a small area depending on elevation, and the steep topography also means that clouds are forced to rise and/or descend rapidly in a small area resulting in lots of rainfall. And with the diversity of temperatures and rainfall, there is so-called “altitudinal zonation,” meaning that many different habitat types (lowland forest, cloud forest, scrub/grassland, alpine areas, etc.) can occur very close to each other. More biodiversity. And any time high-elevation and steep mountains are found closer to the equator, the biodiversity is amplified.

Like this:

And the high-elevation ridges and mountain-tops of the tropical Andes occur in very narrow bands, mostly limited to within the political borders of the nation-states of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. The higher slopes of the tropical Andes are home to cloud forest, and cloud forest provides a home to many flowers/orchids, and therefore also home to many hummingbirds.

How many hummingbirds?

Here’s a map of predicted species richness taking into account only 276 of the hummingbird species. This comes from a 2021 study. The map is described: “Hummingbird species richness based on the aggregate [...] predictions of 1 km resolution distribution models [...] for 276 species.”

Source:

Diego Ellis-Soto, Cory Merow, Giuseppe Amatulli, Juan L. Parra, and Walter Jetz. “Continental-scale 1 km hummingbird diversity derived from fusing point records with lateral and elevational expert information.” Ecography. Volume 4 Issue 4. February 2021.

Compare the hummingbird species richness map to a map of the tropical Andes:

What did the 2021 study predict?

“The integrated models identified a region southwest of the city of Cali, Southwest Colombia as global 1 km2 hotspot of species richness for the 276 hummingbirds in the analysis (Fig. 5). This region borders Ecuador and covers a wide elevational gradient with 80 predicted hummingbird species.”

In the tropical Andes of Ecuador and Colombia, there are up to 80 different species of hummingbirds living within one single square kilometer of space.

In a small space the size of, like, a city park.

80 hummingbirds.

Think about the array of colors. Hummingbirds are celebrated for their vibrant and diverse plumage.

How many shades of violet, blue, hot pink, orange, in just one square kilometer, perhaps on just one hillside?

Consider this:

Across vast regions of North America, there are usually between one and maybe four species of hummingbirds present. But in the tropical Andes? Dozens of species on a single slope.

More species of birds live within Colombia than in any other nation. About 1,900 species of birds live in Columbia.

One-fifth, 20% of all bird species on the planet can be found in Colombia.

Of 360-ish species of hummingbirds on the planet, about 165-ish or more can be found within the borders of Colombia. And at least 15-ish species of hummingbird are endemic to Colombia, meaning that they only live within Colombia.

Among the endemic species of hummingbird in Colombia, the green-bearded helmetcrest only lives in Eastern Andean paramos habitats where it has a close association with the flowers of the unique high-elevation espeletia plant. The critically endangered dusky starfrontlet only lives between 2300 and 3500 meters of elevation near Colibri del Sol ProAves Reserve. And on the mountains of the Caribbean coast, there is the endemic Santa Marta blossomcrown, found up to 1700 meters in elevation. And above that? On the same slopes? The critically endangered blue-bearded helmetcrest only lives above 3000 meters of elevation in rugged habitat along the Caribbean coast in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

This is the power of the tropical Andes, the same mountains that were the original home of tomatoes and potatoes, where the headwaters of the Amazon are born.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venusaur - a giant, probably the largest amphibian alive today. They have a strong symbiosis with the plant on their back, the plant gains mobility and a better chance of reproduction, while the animal gets some of energy from photosynthesis. The adult Venusaurs "plants" the seeds on the back of the newborns, called "Bulbasaur". The young spend most of their time in the forest, but when the flower is ready to bloom, they move to grasslands to help the plants get more sunlight, they're then called "Ivysaurs". They feed on a variety of plants, such as grass and berries. Despite being amphibian they aren't closely related to any alive animal today.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last of the Tytonidae in the bracket! Who will go on to face off against the true owls?

Western barn owls live throughout Europe and much of Africa and the Arabian peninsula in a wide variety of habitats, but most especially favoring open woodland and grasslands. These owls mostly eat small mammals such as rodents and shrews, but will also eat birds, amphibians, lizards, and insects. They hunt by flying slowly over ground and pouncing when movement is detected. Western barn owls are usually monogamous, mating for life. After fledging, young remain with their parents for only about a month. Since barn owls have relatively high metabolic rates, they eat proportionally more rodents than other owls and are thereby appreciated by farmers as effective pest control.

Greater sooty owls live in the rainforests of New Guinea and southeast Australia. They mostly eat marsupials and rodents, though occasionally prey on birds, bats, and insects. They especially prefer arboreal prey. These beautiful owls are the largest member of the barn owl family. They are sometimes considered conspecific with the smaller lesser sooty owl.

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Moor Frog (Rana arvalis)

Family: Typical Frog Family (Ranidae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Least Concern

Although pale brown or grey throughout most of the year, male Moor Frogs (such as the individual pictured above) turn a vivid blue colour for a short period during the species’ mating season - it has been observed that females seem to prefer bluer males when selecting a mate. Found across almost all of Europe and Asia, Moor Frogs inhabit a wide range of habitats (primarily forests, grasslands and swamplands, but also environments that are more hostile to amphibians such as tundras, semi-deserts and human gardens) and are typically found around water, seemingly preferring slightly acidic waters with a pH of around 6. Moor Frogs feed on a wide range of invertebrates (particularly beetles, but they also regularly take flies, wasps, bees, hemipterans, spiders, slugs, snails and centipedes), and like most frogs in their family they rarely actively search for prey, instead opportunistically catching any suitably sized invertebrates that come near them using a long, forked tongue attached to the front of its toothless lower jaw, allowing it to be rapidly flicked outwards to ensnare prey using sticky saliva before being quickly pulled back into the mouth to be chewed by teeth on the upper jaw. Although typically nocturnal, members of this species are near-constantly active during the short mating season (which varies geographically but typically occurs at some point between March and June), with both sexes gathering at pools suitable for breeding and males floating in the water and producing bizarre, warbling mating calls in hopes of attracting a female. Female Moor Frogs, which are dramatically larger and stronger than males, prefer males with louder calls and bluer skin, and upon accepting a male as her mate a female will allow him to climb onto her back where he will remain for anywhere from a few hours to a few days in a state known as amplexus - during amplexus the female will periodically lay large clutches of gelatinous eggs, and the male will fertilize them externally. Unusually among frogs of the genus Rana, Moor Frogs have been known to frequently engage in multi-male amplexus in which several males will cling to a female’s back and all compete to fertilize her eggs. Tadpoles of this species hatch within around 20 days of their eggs being fertilized and often gather in schools to provide protection from predators, feeding on algae, aquatic plants and tiny invertebrates for the first 12-14 weeks of their lives before developing into froglets and transitioning to a diet of small arthropods such as mites and springtails, finally reaching full maturity at 2-5 years of age. During the winter Moor Frogs hibernate in damp, sheltered environments, and (owing to a range of substances in their tissues and blood that allow their cells to withstand damage done by ice formation, known as cryoprotectants) can survive their bodies partially freezing with no lasting consequences.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/25488-Rana-arvalis

#Moor Frog#moor frogs#frog#frogs#zoology#biology#Herpetology#amphibian#amphibians#herpetofauna#animal#animals#wildlife#asian wildlife#european wildlife#blue frogs :)

49 notes

·

View notes