#homeless count

Link

The number of people experiencing homelessness in Long Beach increased by over 1,300, according to the city's point-in-time count data, which the city released Friday afternoon.

0 notes

Text

random thought: when we count female killers we don't count women who have someone do the killing for them (like the state or family members) or women who kill disabled people they care for (whether as a nurse or another type of caretaker)

#m.#like how many white women would be murderers if we counted getting someone shot for being black in her general vicinity#or homeless or queer etc etc

986 notes

·

View notes

Text

prev

———

For some reason the lack of a little jingling bell throws her off.

It’s a quintessential diner thing, she supposes. A little bell above the door. There’s the weird decor and the pressed cotton uniforms and the yelling chef and the little bell. It was in both Back to the Future one and two. That’s how she knows she’s right.

But when she pushes open the door with windows so caked with grime she can hardly see through them, there is no little jingle. And when she looks up at the door frame, eyebrows furrowed, it seems sad and lonely. She’s never been so aware of the lack of a sound, the absence of a noise. It makes the rest of the silence of the diner seem eerie, wrong. Dead.

She takes a hesitant step forward, door swinging shut behind her. She realizes as she approaches the ordering counter that her hand rests palm cupped on her belly, and removes it immediately.

“Hello?”

There are a couple groups of people in the back, talking quietly over their food. It doesn’t make the diner seem any less abandoned, somehow. If anything it feels like a TV playing on mute in a hospital. Saturated static.

“Seat yourself, girl. You ain’t never been to a diner before?”

The woman that speaks is tall and plump and harsh-looking. A very strange mixing of features. They’re at odd with the diner-specific yellow uniform she wears, collar pressed but skirt wrinkled. Apron dusted with flour and streaked with machine oil. Face pinched, eyes hard, black hair resting in dainty ringlets along her shoulders. Her name tag only reads the name of the business.

“A couple,” Naomi defends. “One even had a hostess.”

The woman — who must be a manager — raises an eyebrow.

“You see a hostess’ station?”

“No.”

“Then why haven’t you sat yourself?”

“‘Cause I’m not here to eat.”

“Well, then, get the hell out of my restaurant.”

Naomi holds her gaze, tilting up her chin. She will not be swayed by orneriness. “I need a job.”

The manager eyes her critically. Naomi’s hands twitch, and the top of her head feels suddenly itchy. Summer before highschool she’d wrote her first resume — Mama’d drawn her a bath and sat behind her and spent two hours slowly untangling the ratty mess of curls on her head with nothing but a bottle of cheap jasmine conditioner and her own two fingers, telling her about lasting first impressions.

“Go home, kid.”

“I’m not a fu —” She stumbles over her words at the last second, catching herself before that eyebrow can climb any higher. It does, and the other eyebrow begins to climb with it, but she rights herself and powers on. “I can vote,” she says finally. “I can throw on a uniform and get blown up across seas. I can — I can adopt a child, if I so choose. Right now.”

The eyebrows reach critical height, brushing the end of her carefully teased hairline. Naomi watches them and their inspiring journey with intensity, instead of noticing how the manager’s eyes drop down to her stomach, linger, and then return to her face.

“You gonna adopt it right outta your womb, or what?”

Naomi snaps her mouth shut.

“Well,” she says, and nothing else.

The manager sighs. “This ain’t a charity.”

Naomi barely manages to bite the snark back from her voice before she speaks.“I’m not asking for charity. I’m asking for work.”

Eyes shifting to the tables in the back, the manager leans over the counter, long fingers wrapping around the handle of a coffee pot so old the handle has worn right down to plain metal, and walks over to a beckoning customer. She fills a man’s mug with her lips pressed thin, offering a napkin to a child in a high chair.

“And why would I hire some pregnant kid?”

The customer pushes over a stack of plates without moving his eyes from the newspaper in front of him. There’s a woman on the other side of the table, holding a spoon out to the little kid, eyes desperate and tight smile slipping when the kid’s pudgy fist hits and sends the scoop of scrambled eggs flying. The man brings the coffee to his lips and waves the manager away.

“It’s illegal for an employer to discriminate against a pregnant person,” Naomi says finally. That had been drilled into her head by her Mama, too. That and how to keep her finances separate. She’ll have real trouble with that, what with the zero dollars she’ll have by the end of the week.

“Good thing I’m not your employer, then.” The manager sets the plates by a soapy sink, putting the coffee pot back on the hot plate. “Get lost.”

I am lost, Naomi almost says, almost slamming a hand in the counter to catch herself from her suddenly weak knees. She watches the manager watch her, tight little frown furling the corner of her mouth, through the blur of her eyes, swallowing hard around the lump in her throat.

“Please,” she says, too quiet, then tries again: “Please.”

The manager disappears behind a short half-wall, following the sound of an oven dinging. Naomi gasps silently, bowing over the counter, breathing heavily. She curls her hands into fists and presses them, hard, one to her chest and one right under her ribs. Ka-thump, ka-thump, kickkickkick. Kickkick ka-thump, ka-thump, ka-kickthump.

There’s an echoing clatter as a hot tray slams on a stove top. Scrambling upright, Naomi lifts the little door on the counter, scanning the space. The register is ancient and yellowed, buttons so worn with use the labels have worn away. There’s a thread-thin mat at the base of it. The counters are clean but scratched, walls stained but dust-free. The coffeemaker gurgles pathetically. An apron hangs from a hook nailed to the wall by the kitchen window.

As quietly as she can, Naomi slips it over her head. It’s tight around the waist, so she folds it once and ties it around her ribs, instead, letting the straps dangle loosely at the butt of her jeans. She ties her hair quickly behind her head and steps up to the creaky sink, silently moving the pile of dishes to the empty counter. When the clatter in the kitchen starts up again, she turns the water on as quick as she can — hack gurgle rush — and squeezes the mostly empty soap bottle as hard as she can to make up a lather.

“Hell are you doing?” says the manager gruffly, two pies balancing on her oven mitt hands.

Naomi shrugs.

“You deaf, or stupid?”

She thinks if laughter like a lyre and sun golden hair, plucking at her out-of-tune guitar string and asking a similar question. The ghost of a smile pulls across her face.

“Not deaf. And that’s rude.”

A pie plate crinkles under the press of a knife, and the scent of candy cherry mixes with slightly-burnt coffee. Makes her think of Grammy’s house, the smell of the jams she spent sixty years making soaked permanently in the wooden foundations. The manager finishes plating the pie slices and sliding them under the display glass around the same time Naomi suds up the last dirty mug. She watches her red-painted finger tap, tap, tap on her bicep out of the corner of her eye as she rinses it off.

Unplugging the sink, dirty water gurgling as it drains, she points a hesitant elbow at the dishtowel tucked into the managers pocket. She grabs it, threading it around her fingers, twisting the worn pink tail.

“Freezer broke two days ago.” She picks at a loose thread ‘til it pulls clean from the rest of the fabric, balling it up and sliding it into her pocket. She tugs on the fabric one last time, then tosses it, bundled, into Naomi’s waiting hands. “Tables in the back better have their bill by the time I get back from fixin’ it.”

Naomi hunches over the sopping dishes to hide her smile, listening to the scritch scritch click of the manager’s shoes as she stomps away.

———

Di doesn’t believe in paycheques.

“Great way to get ripped off,” she likes to grumble, slapping a stack of 20s bundled in a stapled piece of notebook paper into Naomi’s hands every Friday. She doesn’t think much of taxes, either, or lawyers, or racecar drivers. Naomi doesn’t quite understand that last one, but she knows better than to ask. As far as she’s concerned she’s still on probation, and probably will be if she works at the diner for another four months. Or the rest of her life.

On one hand, Naomi doesn’t have a bank account, so a cheque would be useless to her anyway. The cash she can use immediately and whenever she needs it. On the other hand, which is currently occupied with sewing back closed the hole she gouged in her backseat for the seventeenth week in a row, she has nowhere exactly to put that money, so it stresses her out.

Maybe she should look into an apartment.

Of course there are no apartment buildings in Sheffield. But she’s pretty sure Iraan is a big enough town to have a couple, as squat as they may be, and it’s only a twenty minute drive. There’s more to do there, too, so maybe she’d actually have a reason to take a day off every week. It’s not like she can buy a damn house with the less-than 3000 dollars she has saved up.

Waddling out of her car, she ducks into the diner. You’d think she’d be used to the lack of bell, now, but she finds that she still anticipates it; finds that her brain still quietly signals to her ears to prep for it. It always sets her off, a little.

“You’re late,” says Di critically, uniform hanging over her arm, foot tap tap-ing on the linoleum floor.

“I don’t have a starting time,” Naomi says lightly. “On account that I am not your employee.“

Di huffs, rolling her eyes. Naomi rolls them right back, snatching the uniform from her arms on the way to the bathroom. She has to wear Di’s, now, because she doesn’t fit into her old one. Di is much taller and broader than her and the stupid thing hangs down to her mid-calf, awkwardly drowning her shoulders, but it’s the only thing wide enough to cover her belly and Di refuses to let Naomi just wear her regular clothes.

(“You’re indecent,” she always says, sneering at her jean shorts, but Naomi has learned to translate you’re indecent but also you can’t have bare legs around hot oil, which she’s come to appreciate. Sure, Di makes her clean the bathroom whether or not she needs to crawl around in her knees to stay balanced, but she doesn’t want her burned to death, at least. That’s something.)

“And your hair’s unwashed,” she adds, as if Naomi had not walked away. She reaches up and adjusts Naomi’s collar, like that is going to do anything to change the fact that she looks like she’s wearing a collapsed tent. “You’re going to drive customers away.”

Naomi doesn’t say, you open before the community centre does, so I can’t shower in the mornings. She does not say, I spent last night trying to change the oil on my car when I couldn’t lie down to reach it. She doesn’t say, I’m too scared to sleep in the community centre parking lot, because my windows aren’t tinted and I don’t know what’ll wake me up.

She says, “The only thing scaring customers away is your busted attitude,” and scurries into the kitchen before Di can order her to clean the friers.

———

Naomi’s favourite part of the diner is the radio.

She can’t believe that Di allows it, what with her general distaste for joy in all of its forms. But it’s balanced on the window sill watching over the oven, antenna extended out the torn screen, dials permanently stuck on an old forgotten country channel. Naomi likes to hum along as she works, frying potatoes or kneading dough, twirling around the kitchen with a mop or a broom. It’s nice even when she’s cramping, even when her feet are sore — she likes hollering along to Dolly Parton when she knows Di is listening, want to move ahead, but the boss won’t seem to let me, likes the way her little parasite goes absolutely buck wild whenever Willie Nelson comes on. She can hear it even when she’s in the dining area, plates balanced all up her arms (and on her belly, too, which is one of the many things she has discovered it’s useful for), humming along to scratching dorks and scritching napkins, working 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin’.

She amuses herself often by making up lives for the various patrons. They’re close enough to the main highway that they get all sorts driftin’ in, from families with bratty kids who upend their food on the floor for Naomi to clean to men in starched suits who never leave a tip. The regulars she’s gotten to know, like the older, stocky, short-haired woman called Bella who smiles softly at her and leaves more than double her bill every breakfast. Or the two young men, college seniors, she thinks, who come in every Saturday afternoon and laugh loudly and talk about strange subjects and rope her into their conversations when there’s no one around and she’s bored.

Other patrons, though, strangers, she speculates. Like there’s a man in the farthest back corner, now, hunched over in the peeling green vinyl seats, scrawling frantically in a tiny notebook. She imagines he’s a private investigator, chasing a lead, about to discover that the woman on a date on the other end of the diner is cheating on her husband of fifteen years.

“Naomi, if you don’t get your ass back to work.”

She throws her hands up. “There’s nothing to do!”

Di observes the half-empty diner, noting the clean tables, neat counters, sparkling kitchen. Each customer sitting satisfied in their table, coffee mugs full, plates still hefty with food.

“Clean the grout.”

Scowling, Naomi stomps to the kitchen, wrenching open the cupboard under the counter and yanking out the Mr. Clean and scrub brush. It’s an ordeal and a half to get on the floor, wincing at the extra weight on her knees, sitting back on her heels with every spray and keeping one hand on her belly while the other scrubs. I Got Stripes by Johnny Cash starts playing through the radio, and she grits out the lyrics with every drag of the brush through the tiles.

“— and then chains, them chains, they’re ‘bout to drag me down —”

A pair of worn black boots come stomping into her line of vision. Naomi finishes scrubbing at a stubborn smear of grease, relishing in how it submits under her power, then rests her weight on her tired hands and tilts her chin up to glare up at her boss.

“I got stripes, stripes around my shoulders,” she sings defiantly, “chains, chains around my feet —”

“I should whip you, you damn drama queen,” Di says darkly, glaring right back. “Had three separate customers come on up to me askin’ me if I’m mistreatin’ ‘that poor young pregnant girl’.”

Naomi smiles triumphantly.

Di scowls, rolling her eyes hard enough to visibly strain her face, and drops some kind of foam pads at her feet. She stomps off without another word, scowling at the radio.

Poking at the pads, Naomi discovers they’re meant to be strapped to her knees. She slips them on, immediately noticing the relief.

For the rest of her shift, she’s an angel.

Di even almost smiles at her.

———

“Naomi, go home.”

“What happened to kid?” Naomi pants, knuckles going white against the counter. She breathes slowly and carefully through her mouth — in, two, three, four, out, two, three, four, in, two — and grits her teeth, staring determinately at the sticky tabletop until the dizziness fades. “I didn’t even know you knew my name.”

“I don’t.” A roughened hand rests on the small of her back, loosening the too-tight apron straps. “You’re sick, kid.”

“I’m fine.”

She tilts forward. Di barely manages to catch her, settling her slowly on the floor without so much as a comment about how heavy she is.

“The diner is empty, Naomi.” The same roughened hand moves up to the back of her neck, untangling the sweaty strands of hair that stick to her skin. Her voice is unusually soft. “You’re nine months pregnant, kiddo. You need to go home. You need to rest —”

“I need to work.”

With great effort, Naomi shoves her away, standing slowly to her feet. The world is still wobbly and bile climbs up her throat, but she pushes forward, hands half-extended beside her. She reaches back for the wet rag, swiping weakly at the table. An onslaught of nausea makes her pause, mouth clamped shut, breathing quick and deep through dry nostrils.

When she speaks again, Di’s voice is hard. “I’m not asking. Get out of my diner. Go home, or you won’t be allowed back. I won’t be accused of killing some dumbass kid who doesn’t know when to quit.”

“I can’t —” she gags, tears springing in her eyes, desperately trying to wrestle back some control of her body — “there’s nowhere, please, Di, let me —”

She slaps a hand to her mouth, heaving. She hasn’t even — she hasn’t eaten all day. The smell of anything makes her want to vomit. The idea of putting anything more in her body makes her want to peel off her skin. She feels — bloated and freakish and ugly; like an unsuspected astronaut on a sieged spaceship.

Like she’s about to burst.

“Oh, for the love of — Naomi, please tell me you are not nine months pregnant and sleeping in your fucking car.”

Naomi says nothing. She squeezes her eyes shut and tries not to think of Mama’s peony-scented perfume.

“Jesus Christ.”

Stomp, click, stomp stomp. Rattling chain, swishing cardboard. Flicking switch. Turning dial, fading music. Stomp, click, stomp stomp.

Two callused hands on her biceps, dragging her upright.

“C’mon, up you get. Where’re your keys?”

A hand digs around in her apron pocket.

“What, d’you fuckin’ run these over or somethin’? The hell’d you fuckin’ do to these things?”

No jingle on the door. A flipped sign.

“No, obviously you can’t — go get in the fuckin’ passenger seat, dumbass. God.”

Di mutters something about stupid kids and stupider adults, for putting up with them. Naomi smiles tiredly. Daddy used to say that all the time, flicking her on the forehead.

“Roll the window down. You need fresh air.”

The slight breeze coming in from the window is helpful, actually. It’s been a disgustingly hot summer, and Naomi has had to sleep with her windows down to avoid suffocating. She wakes up to mosquito bites in places she frankly did not know could be bitten.

“D’you think you’re going into labour?” Di asks quietly, over Dolly’s crooning. Bittersweet memories, that’s all I’m takin’ with me.

Naomi sighs, shaking her head. Already, the nausea has faded into the background. The sweat cools against her skin, and she stops feeling quite so much like she’s going to die.

“No. It’s only been eight months and a little less than two weeks.”

“…You remember the exact date?”

Well, hello, feverish flush. How I’ve missed you so. Will you do me a favour and cook me alive, while you’re here?

“It was a very memorable occasion,” Naomi mumbles, shrinking back into her seat.

“I see.”

Naomi’s never seen Di look quite so amused before. Her whole face softens, and her brown eyes look warm, for once. Naomi would attack her if she had the strength.

Di cruises slowly down Main St, conscientious of the kids ducking in and out of the shops, laughing with their friends. A tween girl looks over at an older boy and whips back over to her friends when he meets her eyes, the whole group of them descending into delighting shrieks. Naomi watches them with a smile and an ache in her chest. She wonders how Molly’s doing. How Esther’s holding up, how Leela is faring. Jen’s at school, now, all the way up in NYC. She hopes they’re well and tries not to hate them for not being here.

Sheffield’s small, and there’s not a street Naomi hasn’t driven down. She spends most of her free time in the community centre pool or the desert around the diner, sure, but she’s been around. When Di turns on Pine St and follows her all the way down, though, she frowns, looking over and asking a wordless question.

Di doesn’t answer. She’s driven them all the way to the other side of town in less than five minutes, pulling into a gravel parking lot and killing the engine.

“C’mon,” she grunts, climbing out of the tiny car and waiting, arms crossed, for Naomi to do the same.

“Sure, sure, let the pregnant woman crawl out of her own seat. Don’t lift a finger or anything.”

Di rolls her eyes.

As soon as Naomi has struggled her way out of the car, which takes her a good four minutes, Di stalks off. In her harried attempt to follow her, Naomi feels like a duck hopped up on an energy drink.

“What kinda money do you have?”

Naomi looks at her strangely. “Uh, what you pay me.”

“Yes, obviously, I meant savings.”

“What you pay me,” Naomi repeats.

Di purses her lips. “Well.”

She does not finish her thought. Instead, she strides down the gravel driveway, heedless of Naomi’s struggle behind her, until she approaches a squat looking building with ‘OFFICE’ printed on the little window.

“She needs a room,” she says to the clerk sitting behind it, gesturing at Naomi.

Naomi looks at her in alarm.

“Di, I can’t —”

“Fifty a night,” responds the man quickly.

“Try again.”

Di’s response is swift and immediate, ignoring Naomi’s tugging hand. She pulls away, resting her hands on her lower back, swivelling her head between Di and the man.

“Rate’s a rate, Di.”

She’s not surprised this man knows Di — everyone knows Di. But the slant to his eyebrows is unfamiliar, the hands clasped easily behind his head. He relaxes back into a leather office chair, heeled boot hiked up to rest in his knee, whistling absentmindedly in the face of Di’s glare.

“Two hundred a week.”

“Not a chance.”

“I’m not asking, Jed.”

The man — Jed — finally starts to look irate, meeting Di’s jaw-set stare with one of his own.

“I’m sorry, I musta missed something. Did you up and buy this place?”

Di doesn’t answer him right away. She never slouches, always standing at her full height, and she’s mighty tall for a woman. For anyone, really. She has a way of planting herself right in front of the sun, no matter where she is. Jed stares up at her, squinting, cast in Di’s shadow everywhere but where he needs to be sheltered.

“You gotta laundry list of shit you done owed me your whole life, Jed.”

Jed just his chin out.

“I don’t owe her shit.”

Blunt fingers wrap around her elbow. “She’s mine.”

“Ain’t how this works, Di.”

“Says who? You?”

For all her intensity, Naomi doesn’t think Di’ll actually fight anyone. If she would, Naomi would’ve gotten her ass kicked months ago.

(She’s mine. Kiddo. You need rest. Roll down the window.)

(…Well.)

Regardless, a flash of fear flits across Jed’s face. He cuts his gaze from Naomi to Di and then back again, pupils shrinking, and then invariably comes to a decision.

“Two fifty,” he snaps, scowling. “Not a penny less, Di.”

Di nods once. “Fine.”

She tightens the hold on Naomi’s elbow, dragging her away from the window. There’s an echoing bang, bang, bang, interspersed with muffled curses, before Jed stumbles out of a door on the side of the scaffolding. He stomps away without looking back, and Di tugs her along to follow.

“Laundry is your own problem. Clean your own shit. If you miss a payment, I’m kicking you out. Clear?”

Naomi stares. Jed standing in front of another low, old building, but this one is much longer, a door posited every dozen or so feet. A plastic chair sits in front of every door, and every door is numbered.

A motel, Naomi realises.

“Clear, kid?”

“Crystal,” Naomi manages, throat dry. Jed practically throws the key at her head, stomping back to the office. Numbly, Naomi slides it in the lock, pushing open the door.

The room isn’t big. There’s a double bed in the middle, a window in the far side and a dresser under it. A TV rests in a dugout shelf in the wall, and there’re two small doors next to it; a closet and a bathroom, Naomi assumes. Smaller than her bedroom back home.

Much, much bigger than her car.

“You’re gonna have to work another ten hours a week to afford this place,” Di says critically. When Naomi looks back at her, she’s lingering at the doorway, staring resolutely at Naomi’s face. Not a spare glance for the room itself.

Naomi does the math fast in her head.

“Twenty hours.”

Di scowls. “Don’t insult me, kid. Ten more hours a week; make sure you’re early tomorrow. I don’t give a shit if you’re sick again, either.”

Naomi swallows. She smooths a hand over the quilt tucked neatly over the bed — it’s soft, if not warm. The pillow is plump.

God, she’s missed pillows.

“Thank you, Di,” she says quietly.

Di makes a small twitching motion with her head that may, in some lighting, be considered a nod, then stalks off. Naomi sinks into the mattress; surprised at how much her feet aches now that she’s off of them.

She swings them up, kicking off her boots, to rest on top of the blanket. She leans against the rickety headboard. She rests her hand on her swollen stomach and slowly, silently, begins to cry.

“You and me and sheer fuckin’ will, kid,” she mumbles, face crumpling. The constant ache in the small of her back lifts, slightly. She stretches her toes as far as they’ll go and cries harder. “We’re gettin’ there. We’re gettin’ there. We’re gettin’ there.”

———

next

naomi art

#this story has literally consumed my life like i am neglecting my finals to write it#literally the only thing i care about rn#pjo#barely lol#percy jackson and the olympians#hoo#heroes of olympus#pjo hoo toa#naomi solace#will solace#does it count if he’s literally a fetus#i said BACKstory 💀#angst#pregnancy#teen pregnancy#homelessness#original work#?#longpost#my writing#fic

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babs was so right for this they'd be such a fun couple. unironically I'm extremely on board for AzBabs.

Azrael #32 (1997)

#jean paul valley#barbara gordon#mental instability and pseudo-homelessness is NOT a turn off for her!!!#oh he has a body count? who gives a fuck she used to run the suicide squad

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

thought for the day is that its not really unusual for a kid to like drawing, or making silly comics, but the fact that cassie is able to recognize them as gregorys comics means he must have done enough for it to be recognizable + he would’ve shown them to her. my point is that this is like one of the only things we actually know about this kid as a solid fact and not just theory/speculation/headcanon is that he draws. and i will cry about it

#fnaf#security breach#fnaf gregory#im just thinking about how… we dont actually know that much about him#theres no in-game confirmation that ggy is canon so we cant count anything there#and the only thing we can really gather from security breach is that he’s homeless#anyways i love him

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nowhere to really go

#the walten files#twf#sophie walten#twf sophie#art#digital art#procreate#fanart#the walten files fanart#twf fanart#doodle#ok but can we just go over the fact that she’s pretty much been homeless all this time#and yes living in the back of the meat store still counts as legally homeless there’s 4 tiers of homelessness and she’s just a step above#living in the streets in a car or in a tent#actually fun fact her and Jenny living in a hotel counts as legal homelessness too#speaking from my homelessness experience hehe 🫶🏻#tbh the meat store thing would only not count as homelessness if the owner has a specific living space in the meat store like one of those#shops that are a part of someone’s actual house and if the owner stated Sophie as a direct occupant of the home if there was one#sooooo ya hahahaha

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a completed one shot I plan to post on ao3 eventually. (Okay I just don't want it on ao3 before I post the one other one I've been working on). It's a bit of backstory for Wayne and Eddie in the Hawkins Halfway House au. Enjoy!

Wayne sat in his small boat, lazily gripping a fishing pole. The coast was barely visible on the horizon, and his boat was the only one around for miles. His cooler already had his catch of the day to take back to the ramshackle cabin he was staying at during his fishing trip. Now he fished to relax.

He was almost drowsing when he heard the quavering voice. It startled him to alertness. Wayne was alone, too far from any other living thing to hear any voice other than his own and the occasional squawking of water birds. Yet, he could hear it.

Someone was singing. The voice, light and soft, barely floated above the sound of lapping water. Wayne couldn’t make out the words of the song but the tune was almost familiar. It would sound sweet, but the voice was unpracticed, fading in and out, sometimes picking up speed and other times slowing almost to a stop.

Regardless, something about it invited proximity. Unthinkingly, Wayne got to his feet to try to pin down the voice. Thankfully his boat was a modest size, only big enough for a group of four and space for their catch. It was only a couple of yards to the front of the boat, and the voice got louder the closer he got.

He leaned over the rail to see where the voice was coming from and there, a few feet away, a little head bobbed above the water. Dark, tangled curls framed large dark eyes, and floated in the water around it. It was a child.

“What on earth,” Wayne murmured to himself. There couldn’t be a kid here so far from shore and any other boats, without a single floating device in sight. The kid couldn’t be older than three or four years old, how long had they been treading water?

Wayne could feel worry start to build in him but it was dampened as the kid swam closer, making the clumsy song louder. The words of the song were mumbly and slurred together. He didn’t know what the kid was singing but as he listened he knew, suddenly, that the kid was starving.

He felt the hunger like it was his own. The child was so hungry, won’t he feed them? Didn’t he want to fill their belly? Please, please, he would feel so much better if he fed them.

The kid was in his boat now. Their skin was pale, almost iridescent, and their hair tumbled past their shoulders. Their body was small and worryingly thin. It didn’t occur to Wayne to question the child’s nudity and sexlessness aside from the vague concern that perhaps the child was cold. Even that faded to nothing because he knew the kid was hungry, so hungry.

Throughout it all, the child’s voice tripped and meandered through the song. Every now and then, alarm would surface in Wayne’s mind but the child would stumble back into rhythm and the worry faded. Wayne at some point had sat placidly in a vacant seat while he watched the child half walk, half crawl towards him.

The child got to him, tiny hands reaching towards him, and Wayne thought maybe he should pick them up. The calm shattered when the child opened his mouth wider than any human child should be able to, revealing rows of pointed, serrated teeth, and bit down on the closest part of Wayne they could reach. The song dropped abruptly, and Wayne screamed.

The teeth sunk into the thick leather of Wayne’s boot, the points of them barely deep enough to prick at the thin skin of his ankle. Instinctively, Wayne kicked out hard. The child was sent clear to the other end of the boat, banging up against the railing.

The child wailed in pain but it didn’t sound human. It was a piercing, shrill whistle mixed with a strange low moan and intermittent clicks. Wayne scrambled back, falling off the seat and smacking his elbow against his cooler. The lid popped open and icy water sloshed over, soaking his sleeve.

The child oriented themself and started crawling awkwardly, quickly, towards him, hungry, hungry, hungry. In a panic, Wayne plunged his hand into the cooler, grabbed one of the fish and flung it at the child. The fish slipped and flopped across the floor. The second it was in reach, the child snatched it up with a triumphant squeal and tore into its belly.

Wayne watched, stunned, as the child ate the whole damn thing, not a single scrap left behind. The child looked up at him with those huge dark eyes, face and hands smeared with fish guts. Wayne’s heart hammered in his chest as the child tried to crawl towards him again. He threw them another fish, and then a third.

By the time the kid finished the third fish, their eyes had gone heavy lidded and a pleased, clicking hum permeated the air. Wayne didn’t give himself a moment to think. He dove forward, scooped the child up, and flung it overboard. The child shrieked but Wayne didn’t care. He started the boat’s engine and sped off towards the coast.

What the fucking hell was that?

–

By the next morning, Wayne convinced himself it had been a nightmare. He’d fallen asleep while fishing and had a horrible nightmare. He didn’t look at the boots he wore yesterday. He decided today he was wearing his spare boots.

Wayne spent hours on his boat, filling up his cooler again with fish of varying sizes. He had started to relax when he heard the trembling singing again. He immediately scanned the water and there, a few yards away, bobbed a little head above the water.

A part of Wayne panicked, but it was small and hard to hear over the stumbling notes of the song. The child swam closer and the song got more audible over the sound of water. The child was hungry again, Wayne could feel it, but it wasn’t the ravenous, hollow bellied hunger from yesterday. Wayne watched the child dig their tiny claws to the side of the boat and climbed in.

Wayne grabbed a fish from the cooler almost before the child flopped on deck. The child snatched the fish thrown at him and giddily bit into it. The song stopped again but by then, the panic Wayne felt lost its mindlessness and became more fearful caution.

He threw the child two more fish and took their distraction to look them over more carefully than he had been able to yesterday. The child’s skin looked human for the most part, aside from the faint iridescence. However, the skin took on a scalier appearance along the child’s calves and forearms, where slight protrusions extended like the fins of a bony fish. There was a smattering of scales along the child’s rib cage, but heavy around the three slits they had on each side.

The child finished the third fish and scrambled over the side of the boat. There was barely a plop in the water. The kid swam fast but they only swam as far as to keep themself out of reach. Then it bobbed in the water watching Wayne, unblinkingly.

Wayne decided to call it a day, and started up his boat.

–

Wayne’s annual fishing trips were two weeks long. He always stayed at an abandoned cabin along the coast of Lake Michigan. Wayne saved his time off every year for this vacation. It wasn’t difficult to do, since Wayne had no family of his own to tend to and he rarely got sick.

Wayne never dwelled on it as he went about his daily routines, but when he was out here on a fishing trip, the loneliness sometimes crept in, uninvited. His parents had passed on years ago and he had no siblings to speak of. His childhood was such that he never had much opportunity to develop any intimate friendships. By the time he reached adulthood, he really never learned how to go about creating said friendships.

He was kind, polite, and quiet. Nobody ever had a single bad thing to say about him, but neither did they ever try to connect beyond the standard pleasantries. It didn’t necessarily bother Wayne; loneliness had lost its sting ages ago, and now carried a gentle familiarity when it visited unexpectedly.

However, Wayne knew that loneliness could do strange things to the mind. He wondered for a while if perhaps he had simply gone crazy. One look at his boots from that first encounter convinced him that it was very real.

–

By the fifth day, the child no longer sang. They also stopped running (swimming?) away right after eating. They stayed in the boat with Wayne for an hour or two. They would watch Wayne unwaveringly. It unnerved Wayne a bit, so to distract them both, he started talking to the kid.

It started with him verbalizing mundane observations (‘sun’s pretty hot today’), to simple recalls (‘last year, I caught a fish as big as you’), to more involved stories (‘the day I was drafted was the worst day of my life, I honestly don’t know how I’ve made it this far in life to meet you’). The child watched him throughout it all. Sometimes Wayne caught them mouthing along as he spoke.

By the eighth day, the child had pinned themself to Wayne’s side. They curled their scaly arms around Wayne’s leg, rubbing their forehead against Wayne’s knee with a happy, clicking hum as Wayne fished. Wayne had taken to giving the child his flannel to wear during their visits, for his own comfort rather than the child’s. The child appeared unbothered by their nudity. The clothing baffled them but they kept it on when Wayne wrapped them up in it.

That evening, Wayne tied his boat to the dock as usual. He gathered up his things and made his way to shore. As he walked, he heard the distinct sound of claws scrabbling wood. When he turned, he caught the child climbing up the wooden pole on the dock. The child pulled themself onto the wet planks of the dock and froze when they saw Wayne.

They stayed that way until Wayne started back towards the shore. He heard small wet footsteps behind him. He peeked over the shoulder to see the child following him. The child once again froze in place. After a moment, Wayne shifted his hold on his things to free up a hand.

“Well? Come on,” Wayne said, arm outstretched. The child beamed, shark teeth on display as his eyes crinkled with joy. The child tugged at the flannel Wayne had tied around his waist, and clumsily put it on before tucking their little hand in Wayne’s.

He gave the kid some more fish for dinner (‘fish!’ the child said, one of the few words they could actually speak) and made them a bed on the lone, lumpy couch in the cabin. The kid let themself be tucked in, though they were plainly confused about the whole thing. When Wayne woke in the middle of the night to use the bathroom, he had a small, heavily sleeping child plastered to his side, little claws hooked in his sleep shirt.

This continued for a few more days. Throughout them, Wayne soaked in the feeling of finally, finally not being alone in the world. The child listened to all his stories, and attempted to tell him stories of their own. They would find things in the water and show the items to Wayne, chattering excitedly. They had started to pick up some of the words Wayne taught them.

It was such a fulfilling time that Wayne began to worry, because his vacation was almost up. They only had three more days left together before he had to leave. The worry twisted his stomach and tightened his throat as the child sat across the rickety card table eating another fish for breakfast.

Wayne decided not to think about it.

–

Leaving the child at the lake on his last night broke his heart. He yelled at them when they tried to follow him on the dock. The child looked so confused. They whistled at him sadly, not even trying for words. Wayne stormed away before his will left him.

He couldn’t say the song woke him because never actually fell asleep. One minute he was tossing in bed and the next a strong, overpowering song flooded his senses and dragged him to the dock wearing only his pajamas.

At the dock, he sat on the damp wood, legs dangling over the edge. In the water there was a person, the most beautiful person he'd ever seen, with long flowing hair and delicate bone structure. Wayne wanted to get closer, needed to be nearer.

The song gentled until it came to a natural end. Wayne’s senses slowly returned to him. Then Wayne saw rows and rows of serrated teeth and impossibly round, large eyes. The person had no nose and their hair looked like seaweed. Not a person. A creature.

Before fear could overwhelm him, he heard excited, happy whistles and clicks. There, not too far from the creature, was the child. They watched the creature with an adoring expression.

“It told me you fed it,” the creature said. The child edged closer to the creature but the creature ignored them.

“Excuse me?” Wayne said.

“The abomination,” the creature said, tilting their head to where the child floated but didn't actually acknowledge them even as they creeped a little closer. “You should’ve let it starve.”

“Did you,” Wayne said as it dawned on him. “Did you abandon them here?”

“It cannot go into deeper waters,” the creature shrugged.

“Is this your kid?”

“I do not know what that–oh, I see. I am technically one of its progenitors, yes,” the creature said coolly. “It is not meant to exist. It is the product of trickery and fertility magic.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“A human wanted to keep me,” the creature said. “The human used some sort of power to create this thing, thinking to tie me to land like a selkie with its coat. The tie didn’t take and now there is this thing in the world. It is a mix of human and siren and it should not exist.”

The child kept swimming closer to the creature, making small entreating chirps. The creature finally acknowledged the child only to eye them dispassionately. When they got too close, the siren pushed them back. The child pouted and drifted at a distance for a while before attempting to get close again.

“I attempted to care for it. Siren offspring are rare. I did not want one to go to waste,” the siren said. “But sirens are hatched nearly full grown. This one is…it should still be gestating in its egg, were it a true siren. It can barely sing. It cannot dive deep. The abomination is hardly functional.”

“So you left them to die?” Wayne asked, aghast. The siren tilted their head.

“I left it. Whether it died or not would be decided by its own actions. The Lakes have little tolerance for the weak.”

The child got close enough again, without the creature noticing. They wrapped their tiny arms around the siren with a sweet smile. The siren reacted violently. With a shrill, angry whistle it grabbed the child by the hair and yanked them off. The child shrieked as the siren sent it spinning in the water.

“What are you doing?” Wayne yelled at the siren. “They just want to be held!”

“I am not prey to be held and drowned,” the siren hissed. The siren bared its teeth at the whimpering child. “Sirens know better than to get close to things larger than them, unless they want to be eaten."

The child’s pitiful sounds made Wayne’s heart ache. The siren, on the other hand, seemed completely unmoved. If the siren cared so little, it made no sense that it was here.

"If you just left it to die, why come back?" Wayne asked coldly.

"I thought I'd be collecting a corpse. I did not want to risk polluting the water with its unnatural state."

Wayne leaned over the side of the dock stretching out his arm and coaxing the child back. The child looked torn. They kept inching towards the siren then squirming towards Wayne when the siren chittered warningly at them. Eventually, the child made their way to Wayne. They reached up to him making little needy clicks. Wayne pulled them from the water and held them close, ignoring how soggy his pajamas with the water dripping from the kid. The siren watched all this blankly. Wayne smoothed down the kid’s hair in an attempt to soothe some of their distress.

“Are you claiming it?” the siren asked.

“What?”

“Are you keeping the abomination?”

“Does it matter?” Wayne asked irritably. “Why do you care?”

“I want to know whether I need to return to retrieve a body later or not,” the siren replied simply.

The kid had burrowed themself into Wayne’s chest. Their little claws caught on the threads of his pajamas as they sang to themself. The song was different from the one Wayne heard from him those first few days. It was sad. Lonely. They seemed to understand that the siren did not intend to stay.

“Well, I ain’t abandoning them,” Wayne said gruffly. “Did you at least give them a name?”

The siren made a sound Wayne couldn’t hope to decipher. At Wayne’s blank stare, the creature seemed amused for the first time.

“I do not know if there’s a human word for it. In our tongue, it means to go against a current or perhaps in a circle. A foolish and dangerous endeavor depending on circumstances.”

Like a whirlpool, Wayne thought, or an…

“Eddie,” Wayne said.

“If you’d prefer,” the siren said. It watched the two of them for a moment, bemused. “If it survives to maturity, you’re welcome to return it to the Lakes.”

“Awfully kind of you to offer,” Wayne said flatly with absolutely no intention of letting go of Eddie any time soon. The siren tilted its head.

“If you say so,” it said. Then it sank in the water with barely a ripple and was gone. Eddie squirmed in his arms and let out a little mournful cry as they tried to get to the water.

“Hush now,” Wayne said softly. “I won’t leave you alone. You’re coming home with me. What do you think of that, Eddie?”

Eddie blinked their big dark eyes at him. Their face broke into a big, toothy smile that two weeks ago would’ve scared the living daylights out of Wayne. Now, in the moonlight, surrounded by the cool waters of Lake Michigan, Wayne found it kind of cute.

#stranger things#eddie munson#wayne munson#sirens#im gonna tag this with#child abuse#just in case#i dont really count what happens as that because it's between supernatural creatures#and i dont think they have the same views or morals as humans?#trensu tells stories#hawkins halfway house for homeless horrors

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbie (2023)

#barbie#barbieedit#barbie 2023#margot robbie#america ferrera#glorbie#my gifs#like this scene is visually pleasing and though it doesn't pass the bechdel test#its purpose is still the opposite of what you'd expect in such a scene in like a romcom#her 'what if he doesn't like me anymore' isn't worry that they won't get to be together#it's about the final step of the barbies taking back what was theirs to begin with#it's not a friend reassuring her she'll win his heart it's about reassuring her their deceitful plan will work#and i'm grateful for it#because when have you ever seen it#it's all i've ever wanted from every movie/show i've watched that featured a romantic het storyline#(j0hn tucker must die and the 0ther woman don't count 'cause they're both about a womanizer#not someone who tried to overthrow the government;brainwash every woman and make them homeless)

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imma be so fr rn if you ship Stolitz you have literally no place in whining about proshippers/comshippers 💀

#Like what exactly do you think that ship is?#“sleep with me or you become poor and homeless. oh btw I will guilt trip you and act like a victim despite having literally all the power#in this relationship physically socially. and emotionally and I fetishize and embarass you in front of everyone you know“#literally what kind of ship is that if not a comship 💀#the fact they also always hate Valentino and Angel#like is rape only rape to you if its violent?#does non violent rape not count?#anti stolas#anti stolitz#anti helluva boss#helluva boss critical#helluva boss criticism#helluva boss critique#helluva critical

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obviously the LOV graciously abstained from infiltrating the top ten this time around because they don’t advocate animal cruelty. Hmph! 😤

#my hero academia#league of villains#i will never forgive them for this#(/three quarters joke)#remember when the league was homeless and starving but couldn’t bring themselves to kill and eat an injured bear bc they felt bad for it?#super paper remembers#*patently ignores how dabi’s response to the bear was ‘’SO WHEN DO WE EAT’’ because he is an outlier and shouldn’t be counted*

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some info about Point In Time counts and statistics around homelessness in the United States!

[ID: Slide 1 of 9, White text on a grey background reads: "Any statistics around homelessness are greatly under-represented, here's why" next to an arrow directing to the next slide, at the bottom, it reads "chronically couchbound"

Slide 2 of 9, in the same style, reads "The numbers that tell how many unhoused people are in the United States are done using something called Point In Time (PIT) counts." the bullet point below it reads: "PIT numbers are used to identify needs for services, and help shelters qualify for funding." The last bullet point reads: "PIT numbers only count people who are legally considered homeless (couch surfing isn’t considered homelessness, legally) This means PIT counts are only counting people in shelter beds, and those visibly sleeping outside."

Slide 3 of 9, in the same style, bullet points read: "Pit counts are the only required count of unhoused people in the US across the country." the next reads: "Every other year, official PIT counts include people not living in shelters, however, many communities try to count both sheltered and unsheltered people every year." The final bullet point reads: "These counts are the closest to an accurate representation of homelessness we have in the united states, and still is lacking."

Slide 4 of 9 reads: "Why?" at the top of the page, below reads bullet points: "PIT counts are done on a random night in January every year." the other bullet point reads: "On this random night in January, it’s often freezing. When I was unhoused in New England winters, I can tell you I wasn’t sleeping outside. I’d stay up and walk around if I couldn’t find a place to crash, and sleep in the daytime. I knew sleep meant death. Most people who do sleep outdoors are usually hidden well because that means warmth and safety."

Slide 5 of 9, in the same theme, bullet points read: "Most shelters simply do not have the funding to staff outreach workers to go out to do full PIT counts. Even if they have the funding, it’s hard to find unhoused people, so staying out the whole night as an outreach worker is difficult." the next bullet point says: "From unofficial counts done similarly to PIT counts in warmer months, it’s easy to see booming numbers of unhoused people. More people aren’t unhoused in the summer, it’s just less dangerous to sleep outdoors."

Slide 6 of 9, in the same style, bullet points read "PIT counts especially misrepresent unaccompanied youth, disabled people, and other marginalized people, because they’re often couch surfing or more hidden from the public while homeless. Couch surfing is not legally considered homelessness." The next bullet point reads "Many communities report zero unaccompanied unsheltered youth, which is often inaccurate in reality." The final bullet point reads: "Lack of youth shelters, and beds in youth shelters, play a huge part of this discrepancy."

Slide 7 of 9, in the same style, bullet points read: "The lack of knowledge, safety, and support in accessing services makes it harder for youth to be connected with service providers and less likely to be counted in PIT numbers." The next bullet point reads "Increasing awareness of PIT counts, and local service providers could help give more accurate counts, but we need more youth-based services that have active outreach teams in order to achieve better (and more accurate) counts of unhoused youth."

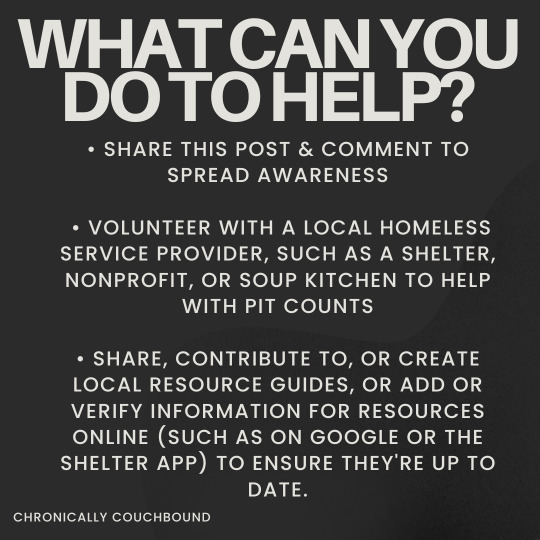

Slide 8 of 9 reads: "What can you do to help?" at the top of the page, below reads three bullet points: "Share this post & comment to spread awareness" The next bullet point reads: "Volunteer with a local homeless service provider, such as a shelter, nonprofit, or soup kitchen to help with PIT counts" The final bullet point reads: "Share, contribute to, or create local resource guides, or add or verify information for resources online (such as on Google or the shelter app) to ensure they're up to date."

Slide 9 of 9, the text reads : "Follow for more: Chronically Couchbound" Below the text is the logo, a white silhouette of a house, in front of it, a black silhouette of the disability symbol, and behind it, a light grey "prohibited" sign. The logo is on a black square background. End ID.]

#chronically couchbound#homeless#unhoused#houselessness#houseless#homelessness#chronically homeless#couchsurfing#couch surfing#has id#homeless statistics#protect homeless youth#homeless youth#chronic homelessness#poverty#social services#homeless shelter#soup kitchen#point in time counts#pit counts#housing crisis#cost of living#capitalism#abolish capitalism#anti capitalist#abolitionist#leftist#socialism#communism#leftism

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

me sobbing as i stick yet another plot item for eyrie to keep in the inventory constantly

#it a nymeian Lily since I did some side quest stuff#but that brings the count up to like. six items?#the lucent flowers + somh al blooms#the final ShB trial EX item + the larimar#the mashable worms + the nymeian lily#okay okay! the lucent flowers are the closest we have to elpis flowers and they’re from the EW beast tribe quests#and the somh al blooms make me cry too bc of the EW beast tribe#the quote w the EX item makes me cry so that has to stay#otherwise I would Feel So Bad#the larimar is from an Ishgard sidequest w this homeless pick pocket girl who freezes to death#and you’re asked to take her belongings to the sea of clouds to have a better resting place#the larimar was given to them after as a piece saved before thieves could ransack her body#thus eyrie keeps it with them to remember the child by#Mashable worms are more funny ooc bc they are worms made just to be mashed into food#and having a pocket with three worms inside of it is amusing to me#the nymian lilies were after the EW alliance raids#I also have funny orbs in eyrie’s inventory from a side quest that got axed after eureka orthos#it was an optional quest you could do for relic stuff iirc#It got shafted but I think I got extra dialogue when talked to the eureka orthos npc bc I did that weird quest once#it have an orb from labyrinth of the#*labyrinth of the ancients and syrcus tower#THE ORBS WERE USED TO GET AETHER OIL FOR ANIMA WEAPONS#I got desperate once for aether oil sjsjdjd#did the quest once and then. gave up bc it wasn’t worth it#I did pick it up once more and got partway through#and just left it once patch 6.3 came out#and now I’m never giving up the quest sjsjdjd#YOU CANNOT TAKE ME PEARLS FROM ME SQUARE#owen plays ffxiv

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncle Jim... couldn’t be me. All these foster kids he gotta take care of... including his man. The Thailand government owes him checks. He gotta take care of his sisters child, she’s busy hoeing with limited profit (Been gone most of her child’s life, could have been married 3 times over with dead husbands, nothing to show for her work.) Now, coz coz gets his lil’ girlfriend pregnant Uncle Jim is at the pawn shop to do right, it ain’t his seed. His man, college graduate, a professional is at his door, homeless. That grill gate needs a security camera, Medeco lock, and a password. Should’ve called the show Moonlight Beer cause every time he’s stressed he gotta drink... The man can’t even light up a cigarette, it’s not cause of “bad influence “ either, it’s a habit he can’t afford to have cause he’s busy bailing out everyone. All the people that used this poor man... outside of his family as well. Change your name from Uncle Jim to Stranger Jim and buy that one way ticket to anywhere... solo. Jim your man is cute but you need rejuvenation time alone...

#moonlight chicken#I love the love story but run Uncle Jim#RUN#This man is the Red Cross and United Nations#Spoilers#BL series#poor uncle jim#Bless his heart for all he does#His nephew count 1 rude as hell#His sister count 2 I know he's bailed her out many times#Coz Coz count 3#Coz Baby Mama and child count 4 & 5 (I know he buyin' diapers)#Homeless boyfriend count 6#Dead ex boyfriend count 7 (left him to run business alone)#Dead ex boyfriend parents count 8 & 9 (Stole his money his half)#Greedy Landlord not paying for meals count 10#Current boyfriends ex man who hates you count 11 (cab chaperone)#Kaipa count 12... yes I'm counting crying on his shoulders in mourning#Nephews boyfriend count 13... The liquor lie that caused stress#I'm coming for everybody... Set Uncle Jim Free Damn It...#MethodToMyMadnessYemme

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idk maybe inappropriate to say in reaction to other peoples reactions [that I mostly agree with] to current events, lest I be interpreted as disagreeing entirely and undermining what I do agree with. But.

The ideas of “people experiencing mental health crises are more of a danger to themselves than anyone else” and “homeless people are far more likely to be victims of violent crime, often at the hands of other homeless people, than they are to commit violent crime against housed people” are both true and important! But the knee jerk reaction I’ve started seeing from a huge number of people online is like….. essentially denying the circumstances that those facts are trying to debunk….?

Mentally ill people are violent sometimes! Homeless people commit violence against housed people sometimes! These things do indeed happen! You can acknowledge that the odds of the above instances happening are much greater than these without suggesting that the latter Never happen or are so rare they may as well not exist at all lmao

Should you ASSUME that someone IS violent and WILL become violent and is just itching to do something violent to you? No that’s not rational, that’s the point. And feeling that way is what underpins efforts to forcibly remove these people from public view, and ultimately from existence at all.

But if you have legitimate reason, in that moment, to think someone might become violent with you, then no you aren’t an irrational pearl clutching heartless frigid bigot. Like that’s scary !!!! it is permissible to feel scared if you find yourself in that situation!!!!!!!! How did we lose the plot this bad lmfao ?????

#like yeah being sexually harassed by a homeless man when ur minding ur business in public does count!#it’s a bad thing that does happen and shouldn’t happen and idgaf about the circumstances of the person doing it

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

if someone said to you hey i invented the torment nexus and i will pay you oh, i don't know, about 50 dollars to sit in the torment nexus for 6 whole entire hours without leaving or losing your composure. and maybe if people see you in the torment nexus they'll give you some money too. would you do it? would you get in the torment nexus? would you spend 6 hours in the torment nexus for 50 FUCKING US AMERICAN DOLLARS? 50 DOLLARS? WOULD YOU? WOULD YOU FUCKING DO IT?

#you're not allowed to kill yourself in the torment nexus btw. and they will make you do this every day and sometimes its more than 6 hours.#WOULD YOU FUCKING DO IT.#BECAUSE EVIDENTLY I WOULD. IM GONNA FUCKING KILL MYSELF.#this was the worst shift i've ever worked in my entire life and i wasn't even supposed to be there today#and not counting tips i got. 50 dollars. give or take. was it worth it#maybe being homeless isnt that bad. i dont know. maybe it isnt that bad. maybe.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think William's death in the Family Business AU might take place in California actually

#they start travelling bc you can only get away with so many murders in a small town#but william tends to stick to places where seasons aren't as easy to count bc. he's trying#and half failing?#to disguise the passage of time from his immortal kids#so there were a few locations i could have them at but southern california seemed like an interesting option#their accents would get so fucked upon being able to interact with people again lmao#and they would probably be able to chill for a bit without being noticed considering how underserved homeless populations can be there#i think they'd have a vehicle as well#this could be fun to actually write sometime huh#i wonder if they'll still be able to reunite with anyone they knew back in hurricane?#fnaf#fnaf family business au#family business au

10 notes

·

View notes