#the ever-changing meaning of words in the english lexicon

Text

fucked up that since literally can mean literally or figuratively, it's its own antonym

#also shoutout to whoever on the iOS dev team decided that its will always autocorrect to it's.#same problem as ill to i'll.#like literally when has anyone ever wanted to say it's but was too lazy to take like two extra milliseconds to click over to the symbols#and hit the apostrophe#anyways this post was hard to write because it kept changing it's its (as in it is its) to it's it's (as in it is it is)#and i hate that lmao. can't even disable ac because it comes in handy managing to decipher like#the incomprehensibly awful misspellings that come out of me 24/7 (can't see my keyboard straight and keep hitting wrong keys)#ryan's rants#the english language#fuck else do i tag this with#the ever-changing meaning of words in the english lexicon#???? like??

0 notes

Text

Clanmew 101

A Warrior Cats Conlang

[ID: Two Warrior Cats OCs speak to each other. On the left is a calico with green eyes named Troutfur. On the right is a leucistic tabby with pink eyes named Bonefall.]

Urrmeer, Clanmates! And welcome to Clanmew 101!

By the end of this lesson you should have a basic understanding of the most important aspects of Clanmew, the language of the five Clans of cats living around Sanctuary Lake.

You will learn to introduce yourself, choose the appropriate pronoun for a situation, construct simple sentences, describe attributes and understand opening particles, express possession, ask simple questions, and use the Clans’ counting system. This should cover all the basics needed in order to have a simple Clanmew conversation.

Lastly, we'll close out with a vocabulary list, and some translation excercises you can do on your own!

This guide is a massive collaboration, written largely by @troutfur with all vocabulary made by @bonefall. This guide is also available in Google Doc format, and there is a lexicon of over 300 words in this Google Sheet.

We've been working on this for several weeks, and we're beyond excited to bring it to you today!

About Clanmew

Clanmew is a language that emphasizes ranks and relationships first and foremost. The rigid nature of Clan culture is baked into the very structure of their sentences, immediately making it clear what your relationship to a thing is, and where you’ve received information about a subject.

Unlike English, in Clanmew, every line is packed with information about a warrior’s relationships and feelings towards the cats around them, turning even quick exchanges into reaffirmations of where a warrior stands in Clan society.

- Introduce yourself; the lack of a personal pronoun

Two cleric apprentices are meeting each other at a half-moon meeting for the first time. Here’s how they would introduce themselves to each other:

Babenpwyr: Pyrrsmeer! Babenpwyr. Washa-ulnyams shompiagorrl. Pryyp pyrrs?

[Noncombatant-you-hello! Bonepaw. Shadow-clan moon-learning-rank. Question noncombatant-you?]

Powshpwyr: Powshpwyr. Ssbass-ulnyams shompiagorrl.

[Troutpaw. River-clan moon-learning-rank]

Translated to English we have:

Bonepaw: Hello! My name is Bonepaw! I’m a ShadowClan cleric apprentice. And you?

Troutpaw: My name’s Troutpaw. I’m a RiverClan cleric apprentice.

This is a very typical introduction in the Clans. Right away these two cats establish their relationship to each other, which Clan they’re from, and their rank within it.

If you examine the way Bonepaw and Troutpaw tell each other their names, it is immediately notable how they only say them. In Clanmew there is no "first person" pronoun, no word that means "I" or "me", and similarly there is no word for the verb "to be". It is understood that if you say a word by itself, those two parts are implied. Thus Babenpwyr is both Bonepaw’s name and a full sentence that means “I am Bonepaw”.

Similarly when Bonepaw says "Pryyp pyrrs?" There is no word for "are" or "is". "Pryyp" establishes the sentence as a question, and "pyrrs" simply means "you".

There are other nuances to the grammar to explore but first, let's skip forward a few seasons, after Troutpaw and Bonepaw change paths and meet once again under the light of the full moon.

Powshfaf: Babenpwyr, pyrrsmeer!

[Bonepaw, noncombatant-you-hello!]

Babenfew: Nyar, rarrwang gryyr! Babenfew!

[No, outsiderness I-contain! Bonefall!]

Powshfaf: Pryyp kachgorrl rarrs? Ssoen wowa rarrs shai ssarshemi!

[Question, claw-rank outsider-you? On/over outsider-you stars they-shine!]

Translated we have:

Troutfur: Hi, Bonepaw!

Bonefall: No, use the rarrs pronoun with me. It's Bonefall.

Troutfur: Oh, you're a warrior? Congrats!

This too is a common interaction among Clan cats. No warrior ever misses a chance to boast about a newly granted name, especially to a friend who already has their own. Here we see another important feature of Clanmew grammar, the choice of pronoun. Clanmew pronouns have nothing to do with gender, but rather, how dangerous the subject is to you.

This is called…

- Threat Level

How To Choose the Appropriate Pronoun

Using the pyrrs pronoun may be appropriate with a cleric, or an apprentice, or a close friend in your same Clan. But for an enemy warrior it’s inappropriate, or even rude, regardless of if they’re a friend or not. It may indicate you are underestimating them, or worse, that you two are traitorously close to each other.

Each pronoun in Clanmew has a third person ("he", "she", "they") form and a second person (“you”) form. The full list of pronouns and when to use them is given below, from least to most threatening.

(Them/You)

Wi/Wees

The softest, weakest possible way to refer to a person. It is used exclusively for babies, aesthetically pleasing but useless objects, and food. “Mousebrain” is either Wiwoo (them-mouse) or Weeswoo (you-mouse).

Nya/Nyams

This one indicates familiarity and closeness, moreso than with a Clanmate or a trusted ally. It is used for mates, platonic life partners, siblings, and so on. It’s sometimes used on objects that significantly change a cat’s life, such as Briarlight’s mobility device.

Pyrr/Pyrrs

Used for apprentices, medicine cats, elders, exhausted warriors, and other non-combatants, but also for friends. It’s a neutral-weak pronoun. Used incorrectly, it can be patronizing, or over-familiar. This is also used on useful objects, like nests, herbs, Jayfeather’s stick, etc.

Urr/Urrs

Indicates a capable clanmate, carries an implication that they are able to hunt or fight at the described moment. The term carries endearment– the old RiverClan river was referred to with Urrs, for respect. Strong, worthy prey is in this category; RiverClan refers to medium-sized fish with urrs, WindClan uses it for hares, etc.

Rarr/Rarrs

Now we’re in the 'outsider’ category. These are not used on clanmates without insult. Used for things that require extra caution. A lot of twoleg things like fences and bridges are 'rarr’. The cats who live in the barn and other loners are 'rarr’. Warriors in other clans are 'rarr.’

Mwrr/Mwrrs

Something dishonorable, that lives without code. Rogues are tossed into this category before proven otherwise, as are snakes, foxes, badgers, and dogs. This is a serious insult when used for a Clan cat.

Ssar/Ssas

Something powerful and dangerous. Storms, floods, cars. Overwhelming and unpredictable, in a way where its power cannot be contained– can be a high compliment to the respected warriors of other clans, implies the same sort of respect you would give to a natural disaster. Commonly used on leaders of other Clans.

- Objects, Subjects, and Verbs

Constructing a Simple Sentence

In English most sentences have three parts, someone who does an action (a subject), an action that is done (a verb), and something the action is done to (an object). By default English sentences order these three elements in the order, Subject-Verb-Object. But Clanmew orders them differently; Object-Subject-Verb.

Compare these sentences;

“The warriors hunt mice.”

[Simple English statement]

“Mice the warriors hunt.”

[Grammatical equivalent in Clanmew]

Translating this into Clanmew looks like this,

Pi woo kachgorrl urrakach.

[Saw/heard mouse claw-rank clanmate-they-hunt.]

Saw mouse warrior they-hunt.

[Direct translation]

Let’s ignore that first word for now and just focus on the subject, object, and verb.

“Woo” in this context means “mouse” or “mice”. Clanmew makes no grammatical distinction between singular and plural, whether there is only one of the noun or more than one. Likewise, “kachgorrl” means “warrior” without specifying how many or which warrior(s) specifically. Finally “urrakach” is composed of a prefix “urr-”, the pronoun for a clanmate, and “akach” the present form of the verb that means “to hunt”.

A specific named subject can be omitted but a pronoun prefix can never be omitted in a Clanmew sentence. Even the absence of a prefix is considered a prefix itself, meaning “I” or “me”. Thus the speaker’s relationship towards the subject is always specified.

- Describing Attributes

When Bonefall corrected Troutfur's pronoun usage earlier he was using this Object/Subject/Verb (OSV) sentence structure; "Rarrwang gryyr" means "Use the rarrs pronoun with me," but is constructed as "Outsiderness (I)-contain". “Rarrwang” itself is constructed of the pronoun “rarr” and the suffix “wang” which indicates a noun embodying a certain quality.

This sentence construction with the verb “gryyr” and a noun with the “wang” suffix can also be used to describe someone or something with any other attribute. Let’s see the following examples:

Yaowang gryyr.

[Female-quality I-contain.]

"I’m a molly."

The word “yaow” is part of a set with “ssuf” (“male”), and “meewa” (“genderless”).

Pi morrwowang urrgryyr.

[Seen/heard fast-quality they-clanmate-contain.]

"She’s big."

"Morrwo" is part of a set with "Eeb" (small) and "Nyarra" (average).

Urr’rr boe gabpwang mwrrgryyr.

[Whisker-felt strength-quality they-rogue-contain.]

"She’s very strong."

Now, let’s see how you can describe someone with more than one attribute!

Bab boe gabpwang om boe morrwowang rarrgryrr.

[Heard-say very strong-quality and very big-quality outsider-they-contain.]

"She is very strong and very big."

Bab boe gabp-om-morrwowang rarrgryrr.

[Heard-say very strong-and-big-quality outsider-they-contain.]

"She is very strong and very big."

These two sentences may look completely equivalent, but the constructions used here actually convey two different shades of meaning.

In the first sentence, the qualities of strength and bigness are understood to not be related to each other. The size is unrelated to her strength. Perhaps she’s big as in fluffy rather than physically imposing! The second construction indicates very much the opposite, that the bigness and strength are related attributes.

Now you may notice by this point that there’s a little word at the beginning of most sentences. It is called an…

- Opening Particle

Opening particles are used to indicate many things such as where the information conveyed is coming from, that the sentence is a question or command, or even that the sentence is a hypothetical being posited.

In statements that denote facts, there are 5 such particles, indicating the way by which this knowledge was acquired. They are:

Bab

Used for information the speaker does not have first-hand knowledge of. Anything that someone has heard from someone else such as news, gossip, or a report falls into this category. Information in this category is considered the least reliable of all categories.

Yass

Used for information acquired through the smell, taste, or the use of Jacobson’s organ. Metaphorically, it has also been extended to things one believes or thinks, and logical deductions. In its metaphorical capacity it is considered second least reliable.

Urr’rr

Used for information acquired through one’s whiskers. Metaphorically, it also extends to emotions, intuition, and other such feelings. Considered the second most reliable source of information when used as such.

Pi

Used for information one has seen or heard directly. Considered the most reliable form of information in most situations. When it comes to information acquired through multiple sources, if visual or auditory sensations are included “pi” will almost always be preferred.

Ssoen

Used by StarClan it indicates information they have access to by virtue of their alleged omniscience. Used by a regular Clan cat it is used to quote the words of a prophecy or to give one’s words the same weight as StarClan’s. In this second usage, it is most often used to give blessings, such as the phrase Troutfur used to congratulate Bonefall.

The lack of a particle can in a way be thought of as a particle in itself too! This indicates that some piece of information is self-evident to the speaker. Examples of when it is appropriate to omit sentence-starting particles have been explored before: introducing oneself, correcting pronoun usage, stating one’s gender, all concerning the self.

Let’s see some examples in practice!

Bab mwrrworrwang Raorgabrrl mwrrgryyr.

[Heard-say murder-quality Lionblaze he-rogue-contains.]

"I’ve heard that Lionblaze is a murderous rogue."

Yass woo nyyrwang mwrrgryyr.

[Smelled/tasted mouse rotten-quality they-rogue-contain.]

"I have smelled/tasted that the mouse is rotting."

Urr’rr rrarpabrpabrpabr.

[Whisker-felt he-outsider-pummeled.]

"He pummeled (me), I felt with my whiskers."

Pi powsh pabparra Ssbass-ulnyams rarrakachka.

[Saw/heard trout patrol-amount RiverClan they-outsider-hunted.]

"I saw a RiverClan patrol catching trout."

Ssoen ulnyams kafyar-ul ssarshefpa.

[Prophetic clan wild-fire-only they-natural-force-will-rescue.]

"Fire alone will save the Clans."

There are 3 other important particles to introduce; Karrl, Hassayyr, and Pryyp

“Karrl” indicates that a statement is a command.

Bonfaf, karrl piagorrl urrsshaiwo.

[Stonefur, command learning-rank you-clanmate-star-will-kill.]

"Stonefur, execute the apprentices."

“Hassayyr” indicates that a statement is a “what if”.

Hassayyr om pyrrs papp.

[What-if with you-noncombatant (I-)will-walk.]

"What if we went for a walk?"

“Pryyp” indicates that a statement is a question.

Pryyp mew wissuff?

[Question kitten they-harmless-suckle?]

"Are the kittens suckling?"

We will talk more about “pryyp” and asking questions a bit later, but first we’ve got to discuss…

- Possession

The simplest and easiest way to say that a person is in possession of something is to use their name as a pronoun like so;

Pi woomoerr'pbum Yywayashaiwrah

[Seen/heard food-hole-bread Harestar-owns.]

"I see the tunnelbun that Harestar owns."

This is only possible for simple statements, and is possible because 'wrah' is a rare, irregular single-stem verb. But more of that will come in another lesson!

There are more common ways to phrase possession. Compare the following two sentences:

Pi woomoerr’pbum Yywayashai urrwrah.

[Seen/heard food-hole-bread Harestar he-owns.]

"I see that my clanmate Harestar has a tunnelbun."

Pi Yywayashai urrwrah woomoerr’pbm Hrra’aborrl urrnomna.

[Seen/heard Harestar he-owns food-hole-bread Breezepelt he-eats.]

"I see that my clanmate Breezepelt is eating my Clanmate Harestar’s tunnelbun."

In the second sentence, the phrase “Harestar’s tunnelbun” is constructed with the same words of the sentence “Harestar has a tunnelbun”, however, the opening particle is dropped and not repeated. The difference is that the object (“woomoerr’pbum”) has been moved to the end.

Thus the phrase “Yywayashai urrwrah” (“Harestar he-owns”) can be understood in this situation to be an adjective that modifies “tunnelbun” in the second sentence. This construction is not limited only to statements about possession, but this is the most common case in which it is used.

You can make possession even clearer with the connecting particle, "en." For example,

Pi Yywayashai-en-woomoerr’pbum Hrra’aborrl urrnomna.

[Seen/heard Harestar-’s-tunnelbun Breezepelt he-eats.]

"I see that my clanmate Breezepelt is eating the tunnelbun-of-Harestar."

All of these phrasings are perfectly grammatical. The use of a shorter, more explicit construction is a function of style and clarity. It is similar to how the idea could in English be expressed equally with the phrasings “Harestar’s tunnelbun”or “the tunnelbun of Harestar”.

Next, we will learn to ask simple questions.

- Simple Questions

“Pryyp” is a very useful particle! In front of a simple statement, it makes it into a yes-no question. For example:

Pryyp Yywayashai woomoerr’pbum urrwrah?

[Question Harestar food-hole-bread he-has?]

"Does Harestar have a Tunnelbun?"

To answer you have a couple options. You could restate the verb along with an opening particle to specify how you know:

Pi urrwrah.

[Seen/heard he-has.]

"He does, I’ve seen."

But what if he doesn't have one? You can negate the verb with the prefix “nyar”! Make sure to place in front of the verb but after the pronoun:

Pi urrnyarwrah.

[Seen/heard he-not-have.]

"He does not, I’ve seen."

Or you could respond with your opening particle, and a simple yes or no:

Pi mwyr/nyar.

[Seen/heard yes/no.]

"Yes/no, I saw."

But it isn’t the only type of question you can ask with Clanmew. In conjunction with a question word in the appropriate place, you can ask more open ended questions. Let’s see an example conversation from WindClan camp:

Hrra’aborrl: Pryyp woomoerr’pbum yar urrwrah?

[Breezepelt: Question food-hole-rabbit who they-have?]

Yywayashai: Pi Ipipfbafba pyrrswrah.

[Harestar: Seen/heard Kestrelflight he-has.]

In English,

Breezepelt: "Who has the tunnelbun?"

Harestar: "I saw Kestrelflight has it."

In this construction we see some interesting aspects of the grammar. The pronoun “yar” (“who”) replaces the subject in the first sentence, but the verb is still conjugated with “urr”.

This shows that Breezepelt assumes that the answer to his question is going to be a battle-capable clanmate. When Harestar answers though, he uses the “pyrrs” pronoun, as is appropriate when talking about a cleric such as Kestrelflight. Because of how the grammar works, Breezepelt is forced to make an assumption as to what his answer would be and Harestar automatically corrects it.

Harestar could have also answered:

Yywayashai: Pi pyrrswrah.

[Harestar: Seen/heard he-has.]

Which is roughly translated to:

Harestar: "He has it."

With this answer Harestar is assuming Breezepelt will be able to figure out which noncombatant has it... but remember; clerics, apprentices, elders, and even close friends of the speaker are all encompassed by “pyrrs”. It may not be as clear as Harestar thinks it is!

To ask a multiple-choice question using “pryyp”, you could do it like this:

Wishwash: Pryyp woomoerr’pbum wragyr nyom Yywayashai nyom Ipipfbafba mwrrwrah?

[Heathertail: Question food-hole-bread boar or Harestar or Kestrelflight they-rogue-have?]

Hrra’aborrl: Pi (wragyr) mwrrwrah

[Breezepelt: Seen/heard (boar) they-rogue-has.]

Which would translate to:

Heathertail: Who has the tunnelbun, a boar, Harestar, or Kestrelflight?

Breezepelt: "I saw the boar has it."

Without “pryyp”, Heathertail’s question would be understood as a statement. “Either the boar, Harestar, or Kestrelflight has the tunnelbun.” But by starting the sentence with the appropriate particle she was able to convey it was a multiple choice question.

Breezepelt can also choose if he wants to specify "boar," or simply use the rogue pronoun in this situation. Harestar and Kestrelflight are not enemies, and so simply saying "Pi mwrrwrah" would make it clear that the boar has it.

This sentence also brings up the question of pronoun agreement when there’s more than one subject. Remember this; the pronoun of the most dangerous subject always has priority.

We've come a long way and learned a lot! Next, we'll cover the complicated way that Clan cats count and measure.

- Counting

We arrive in WindClan near the end of a harrowing scene. Cloudrunner's mate Larksplash has died in childbirth, and he has been told that because of complications, the litter has a sole survivor.

Hainyoopa: Ul-arra nyams wi? Ul-arra mew-ul wi? Ul-arra arkoor shai ssarakichkar om Ul-arramew ssaryorru!

[Cloudrunner: Whole-amount kin baby-they? Whole-amount kitten only baby-they? Whole-amount existence stars natural-force-they-grab and whole-fraction-kitten natural-force-they-left!]

Cloudrunner: "He’s my whole kin? He, who is only a single kitten? StarClan took everything and left me Onekit!"

With these dramatic words, Cloudrunner declared his son's name; Onekit.

The nuances of this expression of grief are hard to grasp unless one has an understanding of the counting system of the Clans. Clanmew does not count with straightforward numbers; instead, they have fractions associated with a given concept.

Arra = Between 1 and 4 = Amount of pieces of prey that can fit in a mouth.

Used for small quantities of concrete things. This fraction is the closest Clanmew gets to simple counting.

Rarra = 5 = Amount of claws on one paw, amount of Clans.

Used to count body parts or the amount of warriors in a usual patrol.

Pabparra = 9 = Amount of a full day's patrol assignments.

Used to count groups of cats, enough to patrol a territory or run a Clan.

Husskarra = 12 = Amount of whiskers on one side of the face.

Used to count a day’s work, things that are being sensed in large amounts.

Shomarra = Around 30 = Amount of days in a lunar cycle.

Used to count amounts of time longer than a day.

These five “fraction words” are almost always preceded by an adverb specifying how much of that amount. The adverbs paired with the amount words are:

Prra = Beginning, usually one but can be any amount under a “warl”

Warl = Quarter

Yosh = Half

Ark = Three-quarters

Ul = Entire

When they are not preceded by a prefix, they aren’t meant to be taken as an exact number, but as an estimation. Clanmew does not value exactness.

Finally there are two useful phrases that can modify these numbers:

Om owar = And another

Nyo owar = Less another

The choice of number word is based on what is being counted, not what is mathematically most convenient. “Om owar” and “nyo owar” thus are very useful phrases to express quantities over what the usual number for the appropriate counting word is. More rarely they are used to express the concept of “+1” and “-1”. This usage is rare because Clan cats don’t really care that much about precision, especially for amounts over four.

Let’s see some examples:

Ul-pabparra om owar ul-pabparra arrlur.

[Whole-patrol-amount and whole patrol I-compelled.]

"I sent out two patrol’s worth of cats."

Karrl arlkatch praa-shomarra om owar om owar om owar.

[Command will-fight beginning-moon-amount and another and another and another.]

"We will fight 3 days from now."

Shomarra nyo owar ssar.

[Moon-amount less another they-natural-force.]

"The month is a day shorter."

And now let’s see an example of numbers in a brief conversation:

Bayabkach: Pi pishkaf pabparra Hwoo-ulnyams rarrkachka.

[Brambleclaw: Seen/heard red-squirrel patrol-amount Wind-Clan they-outsider-hunted.]

Fofnanfaf: Pryyp arra rarr?

[Brackenfur: Question amount they-outsider?]

Bayabkach: Pi rarra, yosh piagorrl om yosh kachgorrl, rarr.

[Brambleclaw: Seen/heard outsider-amount, half learning-rank and half claw-rank they-outsider.]

Brambleclaw: "I saw a WindClan patrol hunting squirrels."

Brackenfur: "How many?"

Brambleclaw: "An outsider-amount, a quarter apprentices and a quarter warriors."

In this exchange when Brambleclaw says “an outsider-amount” he means a standard 5-member patrol. When he further specifies half warriors and half apprentices he specifies about 2 or 3 are warriors and another 2 or 3 are apprentices.

Here’s another conversation that happened in the middle of a ShadowClan patrol:

Rarrlurfaf: Pryyp woo urrpi?

[Russetfur: Question food you-clanmate-perceive]

Uboshai: Mwyr, pi ark-arra amam pipa.

[Blackstar: Yes, perceive three-quarters-amount toad hear.]

Russetfur: "Do you sense/see/perceive any prey?"

Blackstar: "Yes, I hear three toads."

In this sentence “ark-arra” implies three toads but there may be more. If Blackstar wanted to specify there’s three and only three toads, he could have said “ark-arra ul” (three-quarter-amount only).

There are also numerous very useful idiomatic expressions using the number systems! Let’s look at a few of them.

Gryyr ul-arra arrl!

[I-contain whole-amount I-must!]

"I must do everything myself!"

Gryyr huskarra om owar huskarra arrl!

[I-contain whisker-amount and another whisker-amount I-must!]

"This is all overwhelming!"

Finally, let’s examine briefly why Cloudrunner’s lament about his kit was so despairing.

As you can see from above “ul-arra” would mean “whole amount”. That may not sound particularly emotional but for a Clan cat, for whom life is fundamentally communal, the implication of the whole amount of the smallest possible fraction brings to mind the idea of loneliness.

The names Onekit, Onewhisker, and Onestar (“Ul-arramew”, “Ul-arrahussk”, and “Ul-arrashai”) could very well have been translated as Lonekit, Lonewhisker, and Lonestar.

- Vocabulary:

Down below you will find a vocabulary list used in this lesson.

Particles, threat level pronouns, and number words have been omitted as they are explained at length in the text above.

Some verbs used in tenses other than the present are only given in the present tense. Correct use of the past, present, and future and of different verb forms will be explored in a future lesson.

[If you're craving even more vocabulary, check out the Lexicon]

Common Nouns:

Arrkoor: The universe, existence

Baben: Bone

Bayab: Bramble; blackberry plant (Rubus fruticosus)

Bon: Stone

Borrl: Pelt, skin and the fur on it

Faf: Fur

Fofnan: Bracken

Hrra'a: Breeze

Hussk: Whisker

Ipa: Ear

Ipip: Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus)

Ipo: Eye

Kach: Claw

Kafyar: Wildfire

Mew: Kitten

Nyams: Kin

Pabparra: Patrol

Pishkaf: Red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris)

Powsh: Common brown trout (Salmo trutta)

Pwyr: Toebean; The -paw suffix, used to indicate the rank of apprentice

Raor: Lion

Shai: Star

Skurss: Tyrant; the name of the ThunderClan warrior Iceheart when he was leader of BloodClan

Swash: Tail

Wask: Holly

Wish: Bell heather (Erica cinerea)

Woo: Mouse; Food

Woomoerr'pbum: Tunnelbun

Wragyr: Boar (sus scrofa)

Yywaya: Brown hare (Lepus europaeus)

The Clans:

Ulnyams: Clan

Hwoo-ulnyams: WindClan

Krraka-ulnyams: ThunderClan

Sbass-ulnyams: RiverClan

Washa-ulnyams: ShadowClan

Yaawrl-ulnyams: SkyClan

Ranks:

Gorrl: Rank

Shaigorrl: Leader

Arrlgorrl: Deputy

Shomgorrl: Cleric

Kachgorrl: Warrior

Piagorrl: Apprentice

Shompiagorrl: Cleric apprentice

Pronouns:

Owar: Another

Yar: Who

Verbs:

NOTE: All verbs given are present tense.

Akach: Hunts

Akichka: Grapples, grabs

Arrl: Compels, orders; Must

Arrlkatchya: Fights

Babun: Beats (of a heart); In names sometimes translated as the -heart suffix such as Kafyarbabun (Fireheart)

Few: Falls

Fbafba: Flies, is flying (of a bird or winged animal)

Gabrrl: Crackles (of fire)

Gryyr: Contains

Nomna: Eats

Nyoopab: Gallops, running fast

Pabrpabr: Pummels

Pappa: Walks

Pi: To see or hear, to perceive generally

Pipa: To hear

Pipo: To see

Shefpash: Rescues

Shemi: Shines

Sskif: Wants

Ssuff: Suckles

Worr: Kills

Mwrrworr: Kills dishonorably, commits murder

Shaiworr: Executes, kills in StarClan's name

Wrah: Owns

Yorr: To leave behind

Suffixes:

-ul: Only, by itself

-wang: -ness, the quality of being like a thing.

Adjectives:

Eeb: Small

Gabp: Strong

Meewa: De-sexed, genderless

Morrwo: Fast

Nyarra: Of average size

Nyyr: Rotting; Bad

Osk: White

Rarrlur: Russet

Shem: Shining; Good

Ssuf: Male

Ubo: Black

Yaow: Female

Adverbs:

Boe: Very

Mwyr: Yes

Nyar: No

Conjunctions:

Nyo: Less, minus

Nyom: Or

Om: And, plus

Expressions:

-meer: Hello! (Always used with a pronoun prefix)

Ssoen wowa [2nd person pronoun] shai ssarshemi!: Congratulations!

Gryyr ul-arra arrl!: I must do everything myself!

Gryyr huskarra om owar huskarra arrl!: This is all overwhelming!

Try it yourself!

Below are ten open-ended exercises so you can practice and test your knowledge. Feel free to reference the vocabulary list and the main text of the lesson as much as you need. For an extra challenge you can try responding without looking at them or making new sentences of your own!

You’ve just been accepted into a Clan, and even though your leader hasn’t granted you a warrior name yet, they trust you enough to take you to a gathering. How would you introduce yourself to the Cats of the other Clans?

During a patrol you encounter the treacherous and murderous exile Liontail. He tries to appeal to your friendship, but you’re a loyal cat of your Clan so of course you won’t hear this rogue out! Correct his pronoun usage so he knows you’re a threat to him.

You approach the fresh kill pile and smell a rotting squirrel carcass. How would you warn your clanmates?

You are an apprentice and your mentor tells you to check for scents. You can make out 3 unique smells; two strange cats, and a toad. How do you report this to your mentor?

Your clanmate has trouble telling Snowpelt and Whitefur apart. They’re both blue-eyed white cats but while Snowpelt is large and a molly, Whitefur is small and a tom. How would you tell your clanmate this?

Your friend is describing the feared BloodClan leader Scourge, and says they are both small and strong. You want to interject and point out that Scourge was strong because he was small, and often underestimated. How do you phrase this?

While hunting, a rogue attacks your patrol! After the scuffle is over, you notice that the mice you were carrying are gone! Ask your clanmates who has the mice; them, or the rogue.

A RiverClan cat offers you some of the food they brought for the gathering. You know they brought both mice and trouts and you want to make sure you don’t eat any of those smelly fish they are so fond of. Ask them whether they have a mouse or a trout.

You are a RiverClan warrior who just offered a cat from another Clan some of the food you brought to the gathering. The cat in question just asked whether you have a mouse or a trout. It seems kind of obvious to you but it’s only polite to reply. Tell them that you’ve got a trout.

You are the deputy, and you are assigning patrols. At the end, you have 3 cats left over (Kestrelclaw, Hollyheart, and Snowear), and you must ask your leader which of these cats they would like to patrol with.

Once you'd tried them out on your own, you can check your answers over here!

#Clanmew#Conlang#constructed language#grammar#Clan Culture#Warrior Cats#Better Bones AU#Exercises#language#wc#Funfact OSV is the rarest grammatical format#And it's the format Yoda uses when he speaks#We didn't realize it at the time we picked it. It just felt right to emphasise the action last#Linguistics

681 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey so where I'm from "fruity" isn't gendered/isn't just a term used to describe men, it's also not really ever used in a bigoted context and has been part of the mainstream queer lexicon for like, decades. Also, imo people are using it in a positive way so it's not derogatory or homophobic. "Gay" isn't a bad word, but it's been used that way in the recent past which is homophobic. The context changes whether what's being said is derogatory or not. I wouldn't even say it's been reclaimed because it's not a slur. Like, I hate stranger things I'm only saying this as a queer fruit who thinks this sort of black and white focus on language is often more harmful than helpful.

I mean all of this gently, hope you have a nice day 💝

i appreciate you reaching out and sharing your opinion in a civil manner! however, to me this ask screams simplistic (perhaps black and white) interpretation and flat out misreading of my original post & a lack of understanding of queer history or the nuance that is needed here.

- what a word means where you're from specifically is not the only indicator of whether it's offensive or not. my native language isn't english, so obviously "fruit" is not even a term that's used where i'm from. that's no excuse for me to use it online in an inconsiderate manner, though.

- i never said "fruit" was a slur. i don't have an opinion on whether it fits that specific description, but it is offensive regardless.

- the origins of the word aren't 100% clear, so don't claim to know what not even linguistic scholars agree upon. and still, whether it comes from "fruitcake" meaning crazy and diseased or from referring to low income street vendors with "immoral qualities", it's 1) meant as derogatory and 2) currently understood to be offensive.

- i can't believe people are still using the "gay is used as an insult too" argument to try and completely brush over the stark differences between words with positive vs negative origins, connotations, and histories.

- again, in this case idk and idc what it means where you're from specifically, but universally it absolutely is overwhelmingly used to refer to men. the widespread use of the word as a quirky catchall lgbt term is a very recent online phenomenon. for sure some circles have always had different interpretations of the term, but here we are talking about being considerate in an online environment in the modern day where a majority of people associate the word with being derogatory and mlm-targeted.

- the connotations of a word depend on the context, yes. i can call my best friend the f slur and he can call me a dyke & it's a jokey bonding thing that comes from love, not hate. but 20somethings on tumblr using the word "fruity" to refer to some tv show characters (none of whom are even mlm) as a funny bit is not the same fucking thing. idc if they think they're using it in a positive way - it's just insensitive.

- idk what about the sentiment "non-mlm shouldn't throw mlm-targeted insults around carelessly" is black and white to you. i'm not even telling off any specific person or trying to completely revoke anyone's right to use the word "fruit", especially as a self descriptor. i think you identifying as a queer fruit is fucking awesome! but if you feel attacked by the aforementioned statement, maybe you're the one that needs to take a step back and consider the nuances of words like this, including the hurtful connotations.

tl;dr: "fruit" is and has always been a predominantly offensive and mlm-targeted word, i'm all for queer evolution, reclaiming our hurt, and intracommunity solidarity/sharing, none of those nuances apply to non-mlm jokingly gunning for "the fruity four" as a go-to fandom term as if it's just another word.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome! Wattunkáu ruwün!

This blog is dedicated to translating various things into the New Ithkuil language, created by John Quijada. I am neither JQ nor affiliated with him.

What is Ithkuil?

Ithkuil is an engineered language (sometimes shortened to engelang) created with the purpose of "express[ing] deeper levels of human cognition more overtly, logically, and precisely than natural languages", as well as greatly reducing semantic ambiguity. In short, it allows adding a lot of nuance in comparatively very few syllables — which does not mean it is exceedingly compact.

The language has gone through four revisions since its first one all the way back in 2004, and its latest (and most likely last) one is called New Ithkuil. Its grammar is described in detail on the official ithkuil.net website. For more information on the language and resources, check out the comprehensive (fan-run) ithkuil.place website.

This blog

On this blog I'll be translating various tumblr posts I come across that I deem interesting enough. If you have any suggestions, do send them my way through asks.

The New Ithkuil Lexicon is massive, with over 6000 distinct roots. Bear in mind it was entirely made by a single man! These mostly describe basic and general concepts. If more complicated ones appear to be missing, that is because Ithkuil's powerful and versatile grammar allows many complex concepts to be expressed as morphological derivations of simpler ones, rather than taking up a root.

also a truckload of these roots are just biological taxonomy seriously scroll to the end of the document

Despite this, there are a fair amount of lexical gaps in the language, especially when it comes to jargon and specific topics — in this case, the internet and tumblr. For that reason, if there is ever a word or a concept that is too hard to translate in the language, I may coin a new root for it. This way, this blog can also serve as a way to expand the language's lexicon!

Translations

[subject to change, under construction]

Every translation will be composed of multiple parts:

The translation written in the language's romanization, which makes reading and pronouncing Ithkuil easier than the native script.

An intralinear gloss of the Ithkuil sentence, showing how the words are constructed in greater detail.

An approximate literal translation of the Ithkuil text into English, which may often be a bit stilted due to the many ways in which Ithkuil phrases things differently.

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Wednesday's temperature check (3-1)

Rabbit! Rabbit! Rabbit!

Well, it’s March. It’s women’s history month. I’m also re-thinking my understanding of the March weather idiom, “in like a lion, out like a lamb.” I always thought that was an observation like “April showers bring May flowers.” Apparently, it’s a prediction. Well, that’s stupid! There’s been several times when it snows in mid-March. What does that do the prediction? Am I supposed to adjust? What if March comes in like a bobcat, does it end with a rampaging bull? None of this has anything to do with Women’s History Month. Weather is a less controversial topic. Anyway, dictionary.com is adding 313 new terms and 130 new definitions to keep up with the ever-changing modern lexicon. Examples of the new words are "hellscape," "rage farming" and "trauma dumping". They are also adding new cultural terms like "deadass" and "petfluencer". According to our friends at the Oxford English Dictionary, there are 171,146 words currently in use in the English language. This count is a few years old, and OED is not beholden to dictionary.com, so it might be some time before “deadass” makes it. OED and dictionary.com similarly cull obsolete words. For example, when was the last time you were ready to leave a restaurant and the wait staff asked you if you’d like to box your leftovers? There’s not much left and it’s just the julienne cut beets. So you reply, “no thanks it’s just ‘tittynope’.” You’re not going to find ‘tittynope’ in the dictionary. Tittynope has the dual ability to sound dirty, but isn’t and useful in that situation with the waiter. Tittynope means “a small quantity of something left over.”

So, enough fudgelling, I’ve got to get to the day’s activities. (Fudgel (verb): Pretending to work when you’re really just goofing off.)

Stay safe!

Tom

0 notes

Note

Hey! I hope you feel better soon

We haven't had a good long linguistics rant from you in a while!! How about you tell us about your favourite lingustical feature or occurrence in a language? Something like a weird grammatical feature or how a language changed

If this doesn't trigger any rant you have stored feel free to educate on any topic you can spontaneously think of, I'd love to hear it :D

ALRIGHT KARO, let's go!! This is a continuation of the other ask I answered recently, and is the second part in a series about linguistic complexity. I suggest you check that one out first for this to properly make sense! (I don't know how to link but uh. it's the post behind this on my blog)

Summary of previous points: the complexity of a language has nothing to do with the 'complexity' of the people that speak it; complexity is really bloody hard to measure; some linguists in an attempt to be not racist argue that 'all languages are equally complex', but this doesn't really seem to be the case, and also still equates cognitive ability with complexity of language which is just...not how things work; arguing languages have different amounts of complexity has literally nothing to do with the cognitive abilities of those who speak it.

Ok. Chinese.

Normally when we look at complexity we like to look at things like number of verb classes, noun classes, and so on. But Chinese doesn't really do any of this.

So what do Chinese and languages like Chinese do that is so challenging to the equicomplexity hypothesis, the idea that all languages are equally complex? I’ll start by talking about some of the common properties of isolating languages - and these properties are often actually used as examples of why these languages are as complex, just in different ways. Oh Melissa, I hear you ask in wide-eyed admiration/curiousity. What are they? By isolating languages, I mean languages that tend to have monosyllabic words, little to no conjugation, particles instead of verb or noun endings, and so on: so languages like Vietnamese, Chinese, Thai and many others in East and South East Asia.

Here’s a list of funky things in isolating languages that may or may not make a language more complex than linguists don't really know what to do with:

Classifiers

Chengyu and 4-word expressions

Verb reduplication, serialisation and resultative verbs

'Lexical verbosity' = complex compounding and word forming strategies

Pragmatics

Syntax

I'll talk about the first two briefly, but I don't have space for all. For clarity of signposting my argument: many linguists use these as explanations of why languages like Chinese are as complex, but I'm going to demonstrate afterwards why the situation is a bit more complicated than that. You could even say it's...complex.

1) Classifiers

You know about classifiers in Chinese, but what you may be interested to learn is that almost all isolating languages in South East Asia use them, and many in fact borrow from each other. The tonal, isolating languages in South East Asia have historically had a lot of contact through intense trade and migration, and as such share a lot of properties. Some classifiers just have to go with the noun: 一只狗,一条河 etc. First of all, if we're defining complexity as 'the added stuff you have to remember when you learn it' (my professors hate me), it's clear that these are added complexity in exactly the same way gender is. Why is it X, and not Y? Well, you can give vague answers ('it's sort of...ribbony' or 'it's kinda...flat'), but more often than not you choose the classifier based on the vibe. Which is something you just have to remember.

Secondly, many classifiers actually have the added ability to modify the type of noun they're describing. These are familiar too in languages like English: a herd of cattle versus a head of cattle. So we have 一枝花 which is a flower but on a stem ('a stem of flower'), but also 一朵花 which is a flower but without the stem (think like...'a blob of flower'). Similarly with clouds - you could have a 一朵云 'blob of cloud' (like a nice, fluffy cloud in a children's book), but you could also have 一片云 which is like a huge, straight flat cloud like the sea...and so on. These 'measure words' do more than measure: they add additional information that the noun itself does not give.

Already we're beginning to see the outline of the problem. Grammatical complexity is...well, grammatical. We count the stuff which languages require you to express, not the optional stuff - and that's grammar. The difference between better and best is clearly grammatical, as is go and went. But what about between 'a blob of cloud' versus 'a plain of cloud'? Is that grammatical? Well, maybe: you do have to include a measure word when you say there's one of it, and in many Chinese languages that are not Mandarin you have to include them every single time you use a possessive: my pair of shoes, my blob of flower etc. But you don't always have to include one specific classifier - there are multiple options, all of which are grammatical. So should we include classifiers as part of the grammar? Or part of the vocabulary (the 'lexicon')?

Err. Next?

2) Chengyu and 4-character expressions + 4) Lexical verbosity

This might seem a bit weird: these are obviously parts of the vocab! What's weirder, though, is that many isolating languages have chengyu, not just Chinese. And if you don't use them, many native speakers surveys suggest you don't sound native. This links to point number 4, which is lexical verbosity. 'Lexical verbosity' means a language has the ability to express things creativity, in many different manners, all of which may have a slightly different nuance. The kind of thing you love to read and analyse and hate to translate.

But it is important. If we look at the systems that make up the grand total of a language, vocabulary is obviously one of them: a language with 1 million root forms is clearly more 'complex', if all else is exactly the same, than a language with 500,000. Without even getting into the whole debacle about 'what even is a word', a language that has multiple registers (dialect, regional, literary, official etc) that all interact is always going to be more complex than one that doesn't, just because there's more of it. More rules, more words, more stuff.

Similarly, something that is the backbone of modern Chinese 'grammar' and yet you may never have thought of as such is is compound words. We don't tend to traditionally teach this as grammar, and I don't have time to give a masterclass on it now, but let me assure you that compounding - across the world's language - is hugely varied. Some languages let you make anything a compound; some only allow noun+noun compounds (so no 'blackbird', as black is an adjective); some only allow head+head compound (so no 'sabretooth', because a sabretooth is a type of tiger, not tooth); some only allow compounds one way ('ring finger' but not 'finger ring': though English does allow the other way around in some other words), and so on.

You'll have heard time and time again that 'Chinese is an isolating language, and isolating languages like monosyllabic words'. Well. Sort of. You will also have noticed yourself that actually most modern Chinese words are disyllabic: 学习,工作,休息,吃饭 and so on. This is radically different to Classical Chinese, where the majority were genuinely one syllable. But many Chinese speakers still have access to the words in the compounds, and so they can be manipulated on a character-by-character basis: most adults will be able to look at 学习 and understand that 学 and 习 both exist as separate words: 开学,学生,复习,练习 and so on.

I'm going to sort of have to ask you to take my word on it as I don't have time to prove how unique it is, but the ability that Chinese has to turn literally anything into a compound is staggering. It's insane. It's...oh god I'm tearing up slightly it's just a LOT guys ok. It's a lot. There are 20000000 synonyms for anything you could ever want, all with slightly different nuances, because unlike many other languages, Chinese allows compounds where the two bits of the compound mean, largely speaking, very similar things. So yes, you have compounds like 开学 which is the shortened version of 开始学习, or ones with an object like 吃饭 or 睡觉, but you also have compounds like 工作 where both 工 and 作 kind of...mean 'to work'...and 休息 where both 休 and 息 mean 'to rest'...and so on. So you can have 感 and 情 and 爱 and 心 but also 感情 and 情感 and 爱情 and 情爱 and 心情 and 心爱 and 爱心 and so on, and they all mean different things. And don't even get me started on resultative verbs: 学到,学会,学好,学完, and so on...

What is all of this, if not complex? It's not grammatical - except that the process of compound forming, that allows for so many different compounds, is grammatical. We can't make the difference between学会,学好 and 学完 anywhere near as easily in English, and in Chinese you do sort of have to add the end bit. So...do we count this under complexity? And if not, we should probably count it elsewhere? Because it's kind of insane. And learners have to use it, much like the example I gave of English prepositions, and it takes them a bloody long time. But then where?

Ok. I haven't had a chance to talk about everything, but you get the picture: there are things in Chinese that, unlike European languages, do not neatly fit into the 'grammar' versus 'vocabulary' boxes we have built for ourselves, because as a language it just works very differently to the ones we've used as models. (Though some of the problems, in fact, are similar: German is also very adept at compounding.) But as interesting as that difference is, the goal of typology as a sub-discipline of linguistics is to talk about and research the types of linguistic diversity around the world, so we can't stop there by acknowledging our models don't fit. We have to go further. We have to stop, and think: What does this mean for the models that we have built?

This is where we get into theoretically rather boggy ground. We weren't before?? No, like marsh of the dead boggy. Linguists don't know it...they go round, for miles and miles and miles....

Because unfortunately there isn't a clear answer. If we dismiss these things as 'lexical' and therefore irrelevant to the grammar, that is a) ignoring their grammatical function, b) ignoring the fact that the lexicon is also a system that needs to be learnt, and has often very clear rules on word-building that are also 'grammatical', and c) essentially playing a game of theoretical pass-the-parcel. It's your problem, not mine: it's in the lexicon, not the grammar. Blah blah blah. Because whoever's problem it is, we still have to account for this complexity somehow when we want to compare literally any languages that are substantially different at all.

On the other side of things, however, if we argue that 'Chinese is as complex as Abkhaz, because it makes up for a lack of complexity in Y by all this complexity in X' (and therefore all languages = equally complex), this ignores the fact that compounding and irregular verbs belong to two very different systems. The kind of mistake you make when you use the wrong classifier intuitively seems to be on another level of 'wrongness' to the kind where you conjugate a verb in the wrong way. One is 'wrong'. The other is just 'not what we say'. It's the same as the use of prepositions in English: some are obviously wrong (I don't sleep 'at my bed') but some are just weird, and for many there are multiple options ('at the weekend', 'on the weekend'). Is saying 'I am on the town' the same level of wrongness as saying 'I goed to the shops'? Intuitively we might want to say the second is a 'worse' mistake. In which case, what are they exactly? They're both 'grammar', but totally different systems. And where do you draw the line?

Here's the thing about the equicomplexity argument. As established, it stems from a nice ideological background that nevertheless conflates cognition and linguistic complexity. Once you realise that no, the two are completely separate, you're under no theoretical or ideological compulsion to have languages be equally complex at all. Why should they be at all? Some languages just have more stuff in them: some have loads of vowels, and loads of consonants, and some have loads of grammar. Others have less. They all do basically the same job. Why is that a big deal?

Where the argument comes into its biggest problem, though, is that if a language like Chinese is already as complex as a language like Abkhaz...what happens when we meet Classical Chinese?

Classical Chinese. An eldritch behemoth lurking with tendrils of grass-style calligraphy belching perfect prose just behind the horizon.

Let's look at Modern Chinese for a moment. It has some particles: six or so, depending on how you count them. You could include these as being critical to the grammar, and they are.

A common dictionary of Classical Chinese particles lists 694.

To be fair, a lot of these survive as verbs, nouns and so on. Classical Chinese was very verb-schmerb when it came to functional categories, and most nouns can be verbs, and vice versa. It's all just about the vibe. But still. Six hundred and ninety four.

Some of these are optional - they're the nice 'omggg' equivalent of the modern tone particles at the end of a sentence. Some of them are smushed versions of two different particles, like 啦. Some of these, however, really do seem to have very grammatical features. Of these 694, 17 are listed as meaning ‘subsequent to and later than X’, and 8 indicate imposition of a stress upon the word they precede or follow. Some are syntactic: there are, for instance, 8 different particles solely for the purpose of fronting information: 'the man saw he'. That is very much a grammatical role, in every sense of the word.

The copula system ('to be') is also huuuuuuugely complex. I could write a whole other post about this, but I'll just say for now that the copula in Classical Chinese could be specific to degrees of logical preciseness that would make the biggest Lojban-loving computer programmer weep into his Star Trek blanket. As in, the system of positive copulas distinguishes between 6 different polar-positive copulas (A is B), 2 insistent positive (A is B), 19 restricted positive (A is only B), and 15 of common inclusion (A is like B). Some other copulas can make such distinctions as ‘A becomes or acts as B’, ‘A would be B’, ‘may A not be B?’ and so on. Copulas may also be used in a sort of causal way (not 'casual'), creating very specific relationships like ‘A does not merely because of B’ or ‘A is not Y such that B is X’.

WHEW. And all we have in modern Chinese is 是。

I think we can see that this is a little more complex. So saying 'Modern Chinese is as complex as Abkhaz, just in a different way' leaves no space for Classical Chinese to be even more complex...so....where does that leave us?

Uhhhhhh. Errrrrr.

(Don't worry, that's basically where the entire linguistics community is at too.)

The thing is, all these weird and wacky things that Classical Chinese is able to do are all optional. This is where the problem is. Our understanding of complexity, if you hark back to my last post so many moons ago, is that it's the description of what a language requires you to do. We equate that with grammar because in most of the languages we're familiar with, you can't just pick and choose whether to conjugate a verb or use a tense. If you are talking in third person, the verb has to change. It just...does. You can't not do it if you feel like it. There's not such thing as 'poetic license' - except in languages like Classical Chinese, well. There sort of is.

The problem both modern Chinese and Classical Chinese shows us to a different extent is that some languages are capable of highly grammatical things, but with a degree of optionality we would not expect. Classical Chinese can accurately stipulate to the Nth degree what, exactly, the grammatical relationship between two agents are in a way that is undoubtedly and even aggressively logical. But...it doesn't have to. As anybody who has tried anything with Classical Chinese knows, reading things without context is an absolute fucking nightmare. As a language it has the ability to also say something like 臣臣 which in context means 'when a minister acts as a minister'...but literally just means...minister minister. Go figure. It doesn't have to do any of these myriad complex things it's capable of at all.

So...what does this mean? What does all of this mean, for the question of whether all languages are equally complex?

Whilst I agree that the situation with Classical Chinese is fully batshit insane, the fact is most isolating languages are more like Modern Chinese: they don't do all of this stuff. And whilst classifiers and compounds are challenging, they're not quite the same as the strict binary correct/incorrect of many systems. I'm also just not convinced that languages need to be equally complex. However.

HOWEVER. In this essay/rant/lecture (?), I've raised more questions than I've answered. That's deliberate. I both think that a) the type of complexity Chinese shows is not 'enough' to work as a 'trade off' compared to languages like Abkhaz, and b) that this 'grammatical verbosity' and optionality of grammatical structures is something we don't know how to deal with at all. These are two beliefs that can co-exist. Classical Chinese especially is a huge challenge to current understandings of complexity, whichever side of the equicomplexity argument you stand on.

Because where do you place optionality in all of this? Choice? If a certain structure can express something grammatical, but you don't have to include it - is that more complex, or less so? Where do we rank optional features in our understanding of grammar? It's a totally new dimension, and adds a richness to our understanding that we simply wouldn't have got if we hadn't looked at isolating languages. This, right here, is the point of typology: to inform theory, and challenge it.

What do we do with this sort of complexity at all?

I don't know. And I don't think many professional linguists do either.

- meichenxi out

#and that my friends is why I love Classical Chinese so much#askies#meichenxi manages#thank you karo that was very very very interesting!!#it's late now so I'll check over it again tomorrow but I don't imagine I'll be inundated with reblogs lmao#linguistics#lingblr#langblr#classical chinese#chinese#modern chinese

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wonder Of Language, And How It Can No More Be Preserved As An Unchanging Edifice To A Culture Than Any Building Or Monument Can.

Samuel Johnson, 1755:

When we see men grow old and die at a certain time one after another, from century to century, we laugh at the elixir that promises to prolong life to a thousand years; and with equal justice may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change sublunary nature, and clear the world at once from folly, vanity, and affectation.

So to summarize, the belief of mankind that we can preserve our impact, our experiences, our culture, even something as defining as language, against the passage of time is:

Laughable.

Language is especially ready to demonstrate this as viewed by the impact of the rap genre on the lexicon used by the masses via the simplification, truncation and outright creation of new words and meanings to supplement the, (most often), rudimentary poetry of the genre. The effect of that art form has had a more far reaching effect on how the average person communicates than The Beatles ever did on popular culture at their apex.

Just listen to any person under 35 who’s primary music genre of choice was rap. The affectations and pronunciations prevalent in that genre have had more of an impact on the spoken language than any other in the last half century. If you listen, you’ll hear these people speaking English differently, most notably when they pronounce a word with “t” in the middle. They very often will drop it. The t ceases to exist in a word like, “lifting”, which becomes “lif’in” (the “g” at then end of many words and the suffix “ing” is going away too).

Not to put too fine a point on it but “writing” becomes, “rhy’in”. It blares to me, so obvious when I hear talking heads on tv do this, people raised in a time when rap became the prevailing music style, foisted on them by a recording industry keen to maximize profits with lower production and support costs. I note it especially when journalists and news reporters do it.

As Johnson said, it is impossible to protect language from the folly, vanity and affectations of anything and everything that strays from convention. Rap is proof of this just as the ultra rich elites have proven as they work so hard to change all that is sublunary* in our society for their benefit and enrichment, in the immediate term, too ignorant of history to realize their ‘achievements’ will very likely not have any lasting effect and will, in many instances, only serve to hasten their end or the end of their future descendants’ chances of survival on this wee marble. I know that was a bit of a non-sequitur from the topic of language but it’s my blog sooooo: Deal. ;P

We be some dim fecking critters, y’all.

*(beneath the moon, earthly)

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Music Monday #178: Eminem - Stan

release: October 2000

genre: hiphop, horrorcore

cw: drunk-driving, violence, murder-suicide, language

Oh you thought I was a salty bitch before? XD This week we're having a bit of a musical history lesson and digging out an iconic track from all the way back in 2000. And if that doesn't make you feel old yet, then just wait.... ;) Yes, yes, I am a constant surprise in the breadth of my listening habits.

It's a twenty year old song that went through various heavy edit versions because gods forbid MTV play a video that talks about drinking and driving or much of large swaths of the last two verses of this song. Hell, I was half surprised to even find the full length music video, since that was also regularly cut down for content. Even this, the most complete version available, is a cut from the original full version. And then there's this version with Elton John, in which Eminem toned down a couple of the lyrics for television (since this was at the 2001 Grammys).

If you've ever wondered why I tend to react badly to the whole "stan culture" thing, this would be why: I'm old enough to remember that this is where the phrase started, referring to crazy stalker fans who were unhealthy in their obsessions with their targets. Twenty years later and too many people don't realize that "stan" is, or at least was when it entered the lexicon, the English version of "sasaeng" (Korean term for fans who go to dangerous and sometimes outright illegal lengths to get closer to their idols ... like breaking into apartments and tracking down non-idol relatives) and not meant to be aspirational. I know, I know, the meanings of words are allowed to change and drift over time, but the watering down of terms meant to be applied to extreme behaviors normalizes the less extreme versions of those behaviors and that's not always a good thing, you know? We need to be able to talk about things in degrees or people will collapse the thing to the most milquetoast, harmless meaning for the sake of comfort.

When this came out, I was actually still listening to some terrestrial radio and already a fan of both Dido and Eminem separately, so hearing them both together was a whole thing all right. The plot of the song is obviously a bit extreme, but Eminem has long been known for his semi-autobiographical writing, so it wouldn't be surprising if something less extreme but similar had happened to him. Musically, "Stan" is pretty down tempo (so who knows why people feel the need to slow this down even more) with a pretty basic, repeating backing track based off Dido's "Thank You" (which was released like a week or two before "Stan" iirc) that makes this both mellow and melancholy, especially in combination with the rain effects. Given the subject matter, it's an appropriate mood.

It's a guess, but I'm thinking the 'horrorcore' (which comes from the wiki page, not my brain) is probably more from the video than the song, though it could apply to both, considering. The whole run has that horror film vibe, between the run down apparently, the creepiness of the Stan character, the stalker basement, and of course the ending. I'm not even sure which is creepiest, the reveal of little Matthew at Stan's graveside or the last shot of the window next to Eminem. What do you think?

Want to see Music Monday deep dives more often? Sponsor a song selection! For the low, low price of one (1) KoFi, I'll write up the song of your choice. ANY song of your choice. Yes, even that one that's been played to death. Yes, your obscure faves too. With sponsors, I can stop skipping weeks and falling further and further behind in the releases! Sponsor a current CB for the next open Music Monday slot (if I get enough, I'll open Song Sundays so waits aren't more than 4 weeks). Or sponsor a flashback for a Friday feature!

DW | Twitter | Ko-fi | Patreon | Discord | Twitch

#music#music monday#hiphop#horrorcore#eminem#in which jagu features something IN ENGLISH gasp shock#yes people i am a constant surprise#also old. so very old

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome to Seattle (Ch. 1 of 5)

Remus had wanted to move to Seattle for most of his twenties, but when it finally happened it was underwhelming. In all his daydreams, real-estate-app-checking, and job-hunting, he always accounted for an extra person by his side. That extra person was always the same man: the one who Remus had been in a romantic relationship with for the last six years, who Remus had built a life with, who Remus knew like the back of his hand, and who had broken up with Remus an hour before Remus’s 26th birthday party.

A month later, Remus unlocked the door to his Seattle studio apartment, began submitting job applications to local newspapers, and finally started writing his novel. His friends were worried about him being alone, but as he assured them in their daily group-texts, Remus was doing fine. He was finally living the life he had envisioned having for himself, the one he would have had if he had never met his now-ex-boyfriend. If he ate a lot of comfort food and often dined alone, then that was just self-care, not some need for pity from the friends he moved away from.

Seattle was a five hour drive from his past life: the town he went to college in and then never left. Five hours was just long enough to keep his ghosts at bay, but also short enough that his friends could visit him for a weekend. James and Lily were like Remus and his ex: they had met in college and ended up staying and building their lives together. The other bonus about Seattle was that Dorcas and her partner Marlene lived just outside the city. Dorcas had been Lily’s freshman year roommate, and they had been close friends ever since. Once James and Lily got together, the four of them–– Remus, James, Dorcas, and Lily–– formed a group chat and texted constantly. The name of the chat switched a few times a week, but it stayed the same as “Seattle? More like sea ADDLED” ever since Remus moved. After Dorcas introduced Marlene to the group on one of James and Lily’s visits, she was promptly added to the chat.

***

Remus was catching up on the group texts as he sat alone in a booth of the Italian restaurant around the corner from his apartment. He smiled as he read James’s increasingly-frantic texts beginning fifteen minutes ago. Apparently, Lily had set up some sort of parental controls in his phone, and the only change she had made was to prevent him from typing and sending any word that contained the letter “E.”

James: H3LP! I can’t type the l3tter 3

Lily: What? I can’t understand you, I think you’re misspelling words

James: The l3tter 3

*Dorcas changed the name of the chat to “The l3tter 3”*

James: Dorcas. Not h3lping. Lily, did you do som3thing to my phon3??

Lily: Have you tried turning it off and back on again?

James: I only f3ll for that the first 3 times, Lily

Marlene: Do you mean the first three times, or the first E times?

Having finally caught up, Remus joined in.

Remus: James, I think you just need to give up and adjust your vocab to only include words without the letter 3.

James: Stop calling it the l3tter 3, it’s the l3tter 3 and you know that

Dorcas: This is too good

R3mus: See? I adapted

James: W3ll th3n R3mus, l3t’s s33 you g3t by without the l3tter 3

Remus: Without the letter three? That would be tragic

Remus looked up from his phone, still smiling, as the man he presumed to be his waiter approached. Remus’s smile turned to a face of surprise when he looked up at the man’s face. The man was gorgeous. His long black hair was currently braided and tied up into a bun. Remus quickly chastised himself for wondering what it would look like let down before he remembered that he was allowed to think those thoughts again, now that he was unwillingly single.

The waiter’s name tag read “Sirius,” and Remus instantly felt a camaraderie with him for having to get through life with uncommon names. Remus asked for water and a few more minutes to look at the menu, having been distracted by his phone so far. He watched the beautiful waiter walk away, appreciating the fact that his dress shirt was tucked in to tight jeans.

When he returned to his phone, he discovered that Lily, Dorcas, and Marlene were all trying to write sentences without the letter E. So far, Lily was doing the best, but their texts were all punctuated by one or two of James’s “H3LP M3” messages.

Sirius returned with a glass of water and two napkin-wrapped silverware rolls. He placed one in front of Remus, and then held onto the other one somewhat awkwardly.

“Is it just you dining tonight?” He asked.

“Uh. Yep.” Remus answered, hoping his embarrassment hadn’t reached his face yet. He was prone to blush, and his complexion showed it quite visibly.

The waiter seemed almost happy about this–– probably just overcompensating for embarrassing Remus about being alone, Remus thought–– before asking for his order. One margherita pizza ordered later, and Remus got to watch him walk away again.

Remus had been on the hunt for the perfect margherita pizza, and had already tried a few other restaurants in the city. It was Remus’s favorite comfort meal (brownies were considered a comfort dessert). But, since eating an entire pizza for each meal was not “healthy,” Remus had to save the pizza nights for his really bad days.

As he waited for his pizza, he returned to his phone. James had regained the ability to type the letter E, but now they had moved on to voluntarily omitting other letters from their sentences. Marlene and Dorcas were prompting Remus to “blow them away” with his journalist skills, and write a sentence without the letter A. Laughing, he began.

Remus: You think you just did something there, don’t you? Well, I’m sorry to burst your bubble, but numerous sentences could be constructed without the use of the first letter of the English lexicon.

*Lily changed the name of the chat to “Remus ruined the joke”*

*James changed the name of the chat to “Remus ruined the joke gin”*

James: gin

James: wit no

*James changed the name of the chat to “Remus ruined the joke 4g4in”*

James: LILY! WHY C4N’T I TYPE THE LETTER 4

*Dorcas changed the name of the chat to “The letter 4”*

***

The pizza was excellent. Remus decided after the second bite that he had found his oasis. Any bad days in the future would end at this very restaurant, with this perfectly crisp crust and perfectly fresh basil. The pizza was so good that he didn’t even care when the hot waiter came back to ask how everything was and he could only nod and grunt in reply, having just taken a huge bite. Sirius merely laughed and left to take another table’s order.

***

When he brought the check, Sirius also brought a small plate carrying a square layered cake.

“Oh, I didn’t order this, I think maybe it’s for a different table?” Remus said, as the cake was placed in front of him.

“It’s for you, actually, uh, on the house.” Sirius answered, smiling a little sheepishly. “It’s tiramisu, our best dessert here.”

The cake did look familiar, and Remus realized that he had walked past a display fridge full of the Italian dessert when he entered the restaurant. “Oh, well, thank you!” Sirius gave him one last quick smile before turning to take drink orders from a family nearby.

The gesture was sweet, Remus decided. He had been eating alone, new to the restaurant, and the waiter (or more likely owner) had told someone to bring him a free dessert, hoping to persuade him to come back, or tell his friends to visit, or something. It was a good business decision, really. No other strings attached.

Little did the owner know (as Remus had now decided the waiter wouldn’t have brought the dessert unprompted), Remus was already planning on coming back. And, unfortunately, while Remus did have a large sweet tooth, he also had an aversion to the texture of wet cake. The flavor of the tiramisu was good, and Remus could see how other people would like it, but he just couldn’t get over the soggy, coffee-soaked cookie consistency.

He managed to eat half of it, and push the other half around the plate to make it look like he had eaten maybe two-thirds. Remus tipped exactly twenty percent, slid out of the booth, and pulled his jacket on.

Seeing him leaving, Sirius smiled at Remus from across the restaurant, and Remus gave a little wave in return. Sirius was just a friendly waiter, Remus decided, and the free tiramisu didn’t mean anything. Happy about finally finding the perfect pizza place, Remus walked outside, into the cool night air.

#wolfstar#harry potter#original fic#fluff#modern au#non-magic au#seattle#finding yourself post-breakup#found family#writer remus#waiter sirius#humor#great friend group#online dating#remus#sirius#james#lily#dorcas#marlene#dorcas/marlene#minerva mcgonagall#gilderoy lockhart

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

191010 SuperM Aim to Conquer America By Staying Korean

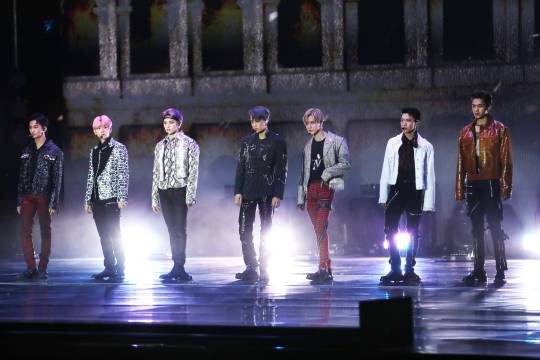

A monolithic coliseum, intimidating and gleaming in the sun, materializes in the desert like a mirage. Inside, seven men clad in black and metallics stand tall in its center, facing the thousands gathered to watch them.

The scene that opens South Korean supergroup SuperM’s debut music video, “Jopping,” is an apt metaphor for K-pop’s most buzzed-about new act — donning their armor, the gladiators prepare to take on one of the most intimidating contenders of them all: the U.S. market.

In August, Korean music juggernaut SM Entertainment, in partnership with Capitol Records and its subdivision Caroline, announced that it would debut a new K-pop supergroup featuring the cream of the crop, pulled from some of SM’s most popular active groups. These acts combined (SHINee, EXO, NCT 127, WayV) have sold more than 14 million adjusted albums and garnered nearly four billion views of their music videos. Though SM has experimented with a few supergroups in the past, this announcement was especially mind-blowing to K-pop fans, as it promised to take a cross-section of some of the very best dancers, singers, and rappers in the business — an Olympic-level performance team.

Taemin, 26, is the industry vet, who joined K-pop darling SHINee as its maknae (youngest member) in 2008. Along with a successful career in the group as its charismatic main dancer, he also has made a name for himself through his popular solo work, dramatic and often androgynous looks, and sultry vocals. From EXO — a group so revered they were chosen to perform at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Closing Ceremony — is SuperM’s leader Baekhyun, 27, known for his killer sense of humor and soaring tenor. Then there’s Kai, 25, the ballet-trained dancer whose secret weapon is a combination of long, sharp lines and arresting looks.

From subunits of the 21-person umbrella group, NCT, is NCT 127’s bright-faced Canadian rapper Mark, 20, and its 24-year-old charismatic leader and rapper Taeyong. And from the Chinese-language unit WayV is the quadrilingual Thai triple-threat Ten, 23, as well as 6-foot-something, 20-year-old striking Hong Kong-born rapper Lucas.

While the announcement garnered a monsoon of excitement online, it was also met with a hefty dose of skepticism and criticism. Some were upset that the activities of NCT 127, EXO, and WayV would be put on hold, and felt bad for the remaining members. But the most vocal faction seemed to float somewhere in the middle, unsure of what to make of the all-star lineup. One thing was sure: the sheer talent would be next-level. But SuperM was notably announced as group aiming to appeal to an international audience and debut in the U.S. — would that mean stripping it of its K-pop identity to make it palatable to the American mainstream?

That fear was all but quelled with one word: “Jopping.” The lead single off of SuperM’s self-titled seven-track EP is a bombastic, genre-bending dance track that blends English and Korean, and even samples the Avengers theme — apt for the self-proclaimed “Avengers of K-pop.”