#thomas carlyle

Text

Nature alone is antique, and the oldest art a mushroom.

-- Thomas Carlyle

240 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

147 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

90 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

強い精神は常に希望を抱き、希望の根拠をもつ。

A strong mind always hopes, and has always cause to hope.

Thomas Carlyle

トーマス・カーライル

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

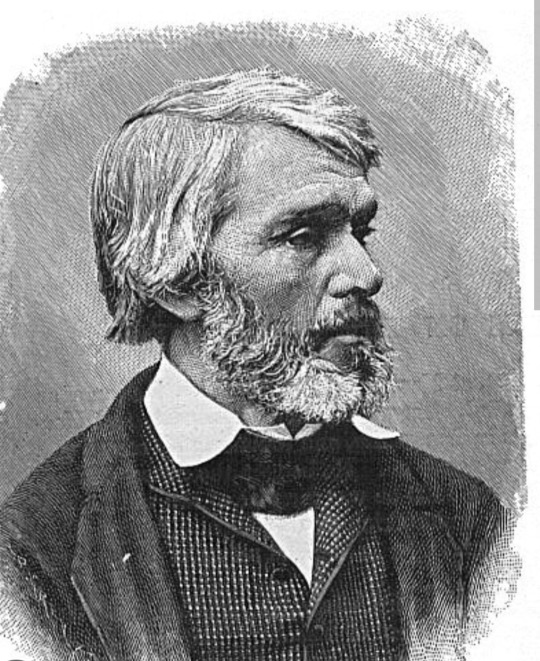

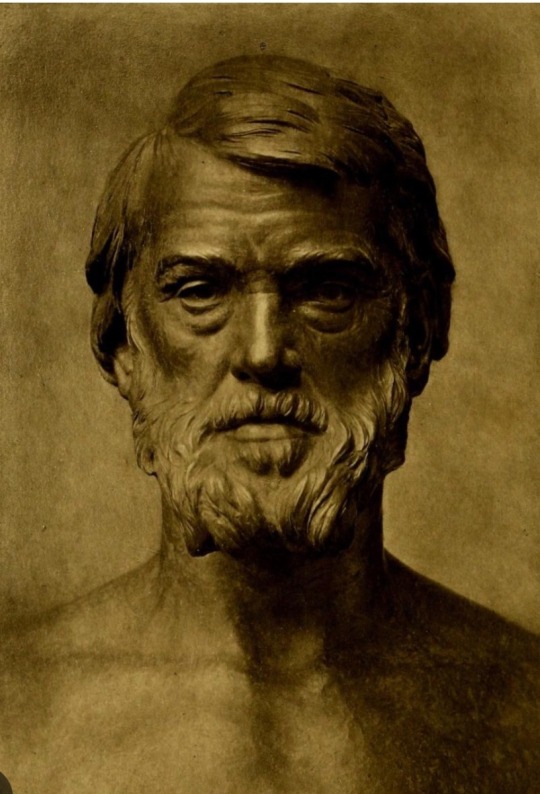

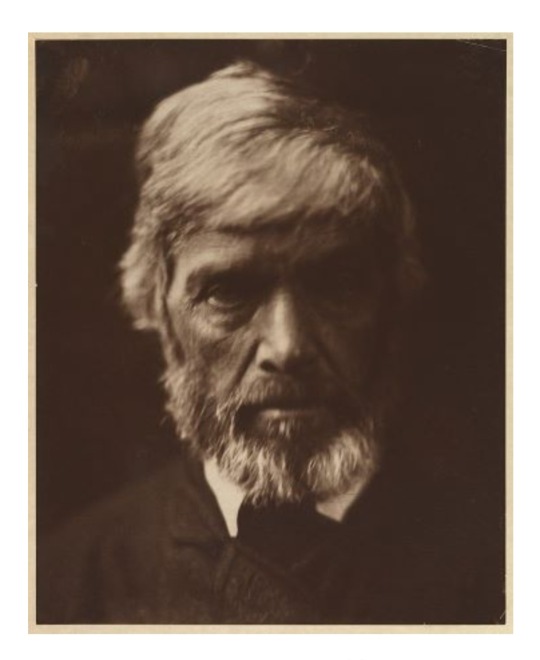

The guy uncannily looks like Jean Valjean.

Thomas Carlyle

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

All sorts of vintage book imagery is here in my virtual stacks.

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Half of It (2020, Alice Wu)

10/11/2023

The Half of It is a 2020 American film directed by Alice Wu. The film is loosely based on Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand.

The film was released on Netflix on May 1, 2020.

#the half of it#alice wu#cyrano de bergerac#edmond rostand#netflix#coming of age story#Genre studies#genre#literature#theatre#film#Video game#Protagonist#coming of age#bildungsroman#literary criticism#bildung#thomas carlyle#Künstlerroman#youth#the poker house#Winter's Bone#Hick#girlhood#mustang#the diary of a teenage girl#mistress america#the edge of seventeen#lady bird#Sweet 20

37 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

180 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Go as far as you can see; when you get there you’ll be able to see farther.

Thomas Carlyle

#Thomas Carlyle#motivation#quotes#poetry#literature#relationship quotes#writing#original#words#love#relationship#thoughts#lit#prose#spilled ink#inspiring quotes#life quotes#quoteoftheday#love quotes#poem#aesthetic

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it. Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry. Nor was the technology they attacked particularly new. Moreover, the idea of smashing machines as a form of industrial protest did not begin or end with them. In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say they were good at branding.

The Luddite disturbances started in circumstances at least superficially similar to our own. British working families at the start of the 19th century were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment. A seemingly endless war against Napoleon’s France had brought “the hard pinch of poverty,” wrote Yorkshire historian Frank Peel, to homes “where it had hitherto been a stranger.” Food was scarce and rapidly becoming more costly. Then, on March 11, 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing center, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

That night, angry workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swath of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north. Fearing a national movement, the government soon positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories. Parliament passed a measure to make machine-breaking a capital offense.

But the Luddites were neither as organized nor as dangerous as authorities believed. They set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered. In one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester. The owner ordered his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18. Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day.

Earlier that month, a crowd of about 150 protesters had exchanged gunfire with the defenders of a mill in Yorkshire, and two Luddites died. Soon, Luddites there retaliated by killing a mill owner, who in the thick of the protests had supposedly boasted that he would ride up to his britches in Luddite blood. Three Luddites were hanged for the murder; other courts, often under political pressure, sent many more to the gallows or to exile in Australia before the last such disturbance, in 1816.

One technology the Luddites commonly attacked was the stocking frame, a knitting machine first developed more than 200 years earlier by an Englishman named William Lee. Right from the start, concern that it would displace traditional hand-knitters had led Queen Elizabeth I to deny Lee a patent. Lee’s invention, with gradual improvements, helped the textile industry grow—and created many new jobs. But labor disputes caused sporadic outbreaks of violent resistance. Episodes of machine-breaking occurred in Britain from the 1760s onward, and in France during the 1789 revolution.

As the Industrial Revolution began, workers naturally worried about being displaced by increasingly efficient machines. But the Luddites themselves “were totally fine with machines,” says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites. They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods,” says Binfield, “and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns.”

So if the Luddites weren’t attacking the technological foundations of industry, what made them so frightening to manufacturers? And what makes them so memorable even now? Credit on both counts goes largely to a phantom.

Ned Ludd, also known as Captain, General or even King Ludd, first turned up as part of a Nottingham protest in November 1811, and was soon on the move from one industrial center to the next. This elusive leader clearly inspired the protesters. And his apparent command of unseen armies, drilling by night, also spooked the forces of law and order. Government agents made finding him a consuming goal. In one case, a militiaman reported spotting the dreaded general with “a pike in his hand, like a serjeant’s halbert,” and a face that was a ghostly unnatural white.

In fact, no such person existed. Ludd was a fiction concocted from an incident that supposedly had taken place 22 years earlier in the city of Leicester. According to the story, a young apprentice named Ludd or Ludham was working at a stocking frame when a superior admonished him for knitting too loosely. Ordered to “square his needles,” the enraged apprentice instead grabbed a hammer and flattened the entire mechanism. The story eventually made its way to Nottingham, where protesters turned Ned Ludd into their symbolic leader.

The Luddites, as they soon became known, were dead serious about their protests. But they were also making fun, dispatching officious-sounding letters that began, “Whereas by the Charter”...and ended “Ned Lud’s Office, Sherwood Forest.” Invoking the sly banditry of Nottinghamshire’s own Robin Hood suited their sense of social justice. The taunting, world-turned-upside-down character of their protests also led them to march in women’s clothes as “General Ludd’s wives.”

They did not invent a machine to destroy technology, but they knew how to use one. In Yorkshire, they attacked frames with massive sledgehammers they called “Great Enoch,” after a local blacksmith who had manufactured both the hammers and many of the machines they intended to destroy. “Enoch made them,” they declared, “Enoch shall break them.”

This knack for expressing anger with style and even swagger gave their cause a personality. Luddism stuck in the collective memory because it seemed larger than life. And their timing was right, coming at the start of what the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle later called “a mechanical age.”

People of the time recognized all the astonishing new benefits the Industrial Revolution conferred, but they also worried, as Carlyle put it in 1829, that technology was causing a “mighty change” in their “modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand.” Over time, worry about that kind of change led people to transform the original Luddites into the heroic defenders of a pretechnological way of life. “The indignation of nineteenth-century producers,” the historian Edward Tenner has written, “has yielded to “the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers.”

The original Luddites lived in an era of “reassuringly clear-cut targets—machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer,” Loyola’s Jones writes in his 2006 book Against Technology, making them easy to romanticize. By contrast, our technology is as nebulous as “the cloud,” that Web-based limbo where our digital thoughts increasingly go to spend eternity. It’s as liquid as the chemical contaminants our infants suck down with their mothers’ milk and as ubiquitous as the genetically modified crops in our gas tanks and on our dinner plates. Technology is everywhere, knows all our thoughts and, in the words of the technology utopian Kevin Kelly, is even “a divine phenomenon that is a reflection of God.” Who are we to resist?

The original Luddites would answer that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart,” it may help, every now and then, to ask which of our modern machines General and Eliza Ludd would choose to break. And which they would use to break them.

#history#labour#employment#capitalism#exploitation#technology#textiles#folklore#industrial revolution#luddites#britain#england#ned ludd#william lee#thomas carlyle#elizabeth i#weaving#knitting#stocking frame

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Using spring recess to catch up on Invisible College reading/podcast, and I wondered if you’d ever read Carlyle’s French Revolution. I attempted it a couple years ago, got maybe 75 or 85 pages in (this is *after* I’d listened to Mike Duncan’s very approachable 45-ish episode podcast on the French Revolution) and Carlyle’s prose and the sheer density of era-specific references utterly defeated me. When people say things like “the internet/podcasts/meme culture” or whatever is the literature of our time, this reading experience is what I think of….

No, just excerpts to get the flavor of the rhetoric and the basic idea, which is essentially reproduced for the common reader by Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities anyway. (Dickens, with his populist touch, doesn't bother us with era-specific references and just presents allegorical social types for his fictional history of the French Revolution. I'm not mocking; it's a good technique!) The only Carlyle book I've read cover to cover is Sartor Resartus, which is difficult in its own way, but not that way. You probably have to know a bit about German Romanticism and Idealism for that book, but not much historical minutiae.

(Speaking of literature, history, meme culture, and our time: a leftist on Xitter said something like what was going on at Columbia this weekend will be better remembered than the contemporaneous Gertrude Stein event. "I'm not so sure," I thought, as I strived—am still striving as we speak—to cram a bunch of Irish history back into my head for the Yeats episode of the IC. Yeats I can remember; the historical context I have to remind myself of every time it comes up. Begorrah, who was O'Leary again? "Let me recite what history teaches. History teaches," wrote Stein inconclusively, as if to say that history teaches nothing. She elevates Picasso's "presently," the permanent present of timeless-untimely art, over Napoleon's "first," the mere successions and usurpations of historical time. She therefore both ventures and cancels the imperious artist's possible resemblance to the emperor. This is her way of agreeing with Aristotle, I take it, that poetry is more philosophical than history, because poetry treats of what might and should happen, while history just tells us, depressingly enough, what did.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

天才とは、無限に努力できる能力のことである。

Genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

Thomas Carlyle

トーマス・カーライル

102 notes

·

View notes