#emperor of germany

Text

Young Prince Wilhelm, future Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia (AKA Wilhelm II).

#all i need to say is smash#kaiser wilhelm#kaiser wilhelm II#kaiser#prince wilhelm#willy#vintage photo#young#old photos#old royal#old royals#hoenzollern#house of hoenzollern#king of prussia#emperor of germany#prince#king#emperor

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

✵ February 27, 1881 ✵

Princess Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein & Prince Wilhelm of Prussia

Later Emperor and Empress of Germany

#germany#emperor of germany#empress of germany#German royal family#german royalty#Prussia#Royal Wedding

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon accepts the surrender of an Austrian army under General Mack on 20 October 1805 (detail)

by René Théodore Berthon

#napoleonic wars#napoleon#napoléon#bonaparte#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#art#rené théodore berthon#ulm campaign#ulm#germany#emperor#empire#france#french#austria#austrian#habsburg monarchy#holy roman empire#history#europe#european#napoleon i#napoleonic#karl mack von leiberich#soldiers#roustam raza#landscape#marengo#horse

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

While there isn't a single definitive "first record" of a transgender person, various historical accounts and cultural practices provide insight into the existence of transgender individuals throughout history.

One notable example is Elagabalus, who reigned as Roman emperor from 218 to 222 AD. Elagabalus was known for defying traditional gender roles and norms, reportedly expressing a desire to be referred to and treated as a woman. Historical accounts describe Elagabalus dressing in women's clothing, wearing makeup, and even marrying men.

Beyond Elagabalus, various cultures throughout history have recognized and accepted individuals who do not conform to traditional gender roles or binary notions of gender. For example, many Indigenous cultures around the world have long recognized the existence of Two-Spirit people, who embody both masculine and feminine qualities and often hold special spiritual or societal roles within their communities.

One notable figure from around the Nazi era who is sometimes discussed in the context of transgender history is Lili Elbe. Lili Elbe was a Danish transgender woman who was one of the earliest recipients of sex reassignment surgery. Born as Einar Magnus Andreas Wegener, she underwent a series of gender-affirming surgeries in the early 1930s under the care of pioneering sexologist Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin, Germany.

Another notable figure who has been identified as a transgender man from around the Nazi era is Karl M. Baer. Born in Germany in 1885, Baer is believed to have undergone a hysterectomy and legally changed his name to Karl in the 1920s. Baer was a writer and editor who contributed to various publications.

Some reputable sources for transgender history include:"Transgender History" by Susan Stryker"Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman" by Leslie FeinbergJSTOR and Google Scholar for academic articles on transgender historyWebsites of LGBTQ+ history organizations and archives, such as the GLBT Historical Society and the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria.

These resources can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the historical record of transgender individuals and the complexities of gender identity throughout history.

Being transgender is nothing new. Trans people have always existed and will continue to do so. Die mad about it.

#transgender#trans man#anti radical feminism#trans#trans rights#fuck jkr#lgbt#terfism#lgbtq#radblr#radical feminism#terfsafe#terfblr#history#roman emperors#roman era#ww2#ww2 history#ww2 germany

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

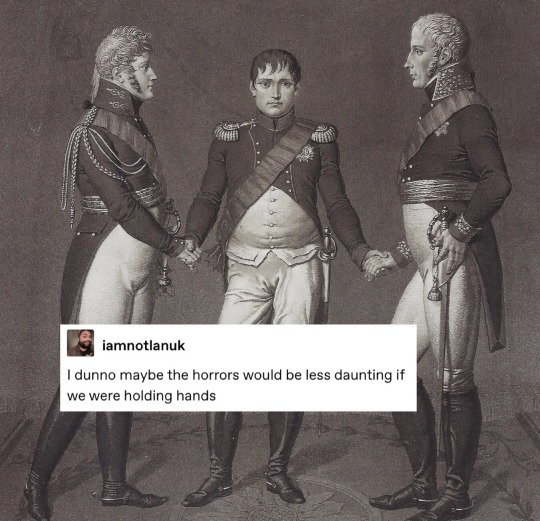

Remember that time when Germany, France and Russia ended their wars for 5 seconds in the 1800s and their leaders released a bunch of propaganda posters of them holding hands

The Treaty of Tilsit, 1807

#napoleonic#napoleonic era#Napoleon#tsar alexander i#Frederick#Frederick William III#Frederick William III of Prussia#Prussia#Germany#Russia#France#first French empire#French empire#Russian empire#tsar#emperor#king#royalty#history#Tilsit#treaty of Tilsit#propaganda#historical propaganda#napoleonic wars#napoleon bonaparte#Bonaparte#19th century#1800s#1807#war of the 4th coalition

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

#countryhumans#countryhumans ussr#countryhumans third reich#countryhumans second reich#countryhumans prussia#countryhumans east germany#countryhumans Holy Roman Emperor#german family

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

EXTREMELY rare photo of Prince Waldemar of Prussia, youngest son of Emperor Fredrick III of Germany and Victoria Princess Royal, 1878 🤍

Source: Hessian State Archives

#I legit almost fainted when I discovered this gem 🤩🥰🤍#rare#rares#hessian state archives#prussian royal family#prince waldemar#Prince Waldemar of Prussia#Waldemar of Prussia#1878#germany#kaiser Fredrick iii#emperor fredrick iii#victoria princess royal#favs

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

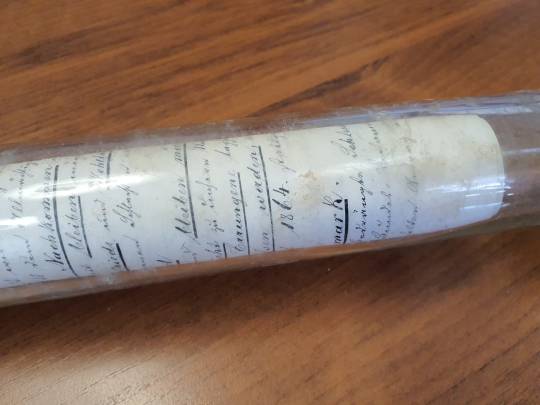

Builders Find Time Capsule Containing 19th-Century ‘Coins and Documents’ in Germany

Builders have stumbled across a German time capsule containing documents and coins from the second half of the 19th century.

The glass capsule was found on Tuesday, March 7, during work on a roundabout in the town of Oława in Lower Silesia when workers removed a previously existing historical column.

Contained in a transparent glass container, documents in German bearing the date 1864 and coins from the second half of the 19th century can be seen.

Several gold, silver and copper coins are visible in the transparent container, but they will only be able to be identified precisely when the capsule is opened.

Oława District Council said: “During the work of moving part of the column, which now stands on the site of a kindergarten, and where a new roundabout is being built - a time capsule was found.

“What exactly is inside the glass container is not yet known. Photos show coins and a paper document. The find will now be dealt with by archaeologists."

However, according to treasure-hunting website Zwiadowca Historii, one of the coins is a silver thaler known as a "vereinsthaler" and was minted in 1866 in Vienna during the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I.

Oława is a historic town in Lower Silesia and was the German town Ohlau before World War Two.

In the 19th century and even earlier, Germans were fond of burying time capsules inside construction projects that they were particularly proud of, for example, bridges and church steeples.

They often included coins and official documents in these capsules, and sometimes handwritten notes and photographs as a way of immortalising their civic efforts for future generations.

Such time capsules are periodically discovered in parts of Poland.

In May 2020, the oldest time capsule ever discovered in Europe from 1797 and equal in age to the oldest in the world was discovered in Lower Silesia during repair work in a former evangelist church in Ziębice.

Meanwhile, in 2019, a time capsule dating back to 1851 buried by the Prussian king Frederick William IV was sensationally discovered during work on an historic 19th-century bridge in the northern Polish town of Tczew.

By STUART DOWELL.

#Builders Find Time Capsule Containing 19th-Century ‘Coins and Documents’ in Germany#Oława#time capsule#archeology#archeolgst#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#emperor franz joseph i

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 8 children of Emperor Fredrick III of Germany and Victoria Princess Royal (edit)

Wilhelm, Charlotte, Henry, Sigismund, Viktoria, Waldemar, Sophia, Margaret

(made by me using iMovie)

#should I do more of these edits?#haha I have already started making more 🤫#🩷🩵🤍#my edit#edits#video edit#prussian royal family#emperor Fredrick iii#kaiser Fredrick iii#fredrick iii#germany#kaiser wilhelm ii of germany#kaiser wilhelm ii#Victoria princess royal#crown princess victoria of Prussia#empress Fredrick of Germany#empress victoria of germany#empress of germany#princess charlotte of prussia#duchess of saxe meiningen#prince Henry of prussia#prince heinrich of prussia#prince sigismund of prussia#princess viktoria of prussia#viktoria of Schaumburg lippe#prince Waldemar of Prussia#waldemar of prussia#princess Sophie of Prussia#queen Sophie of Greece#Princess Margaret of Prussia

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

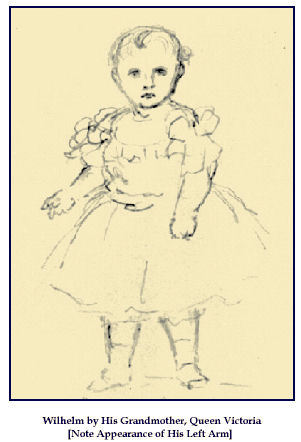

Kaiser Wilhelm II appearance as a baby;

“They say all babies are alike,” wrote one German observer. “I do not think so: this one has a beautiful complexion, pink and white, and the most lovely little hand ever seen! The nose rather large; the eyes were shut, which was as well, as the light was so strong. His happy father was holding him in his arms.”

“He is growing so handsome and his large eyes have now and then a dreamy expression and then again they sparkle with fun and delight.”

- Victoria, Princess Royal writing to her mother, Queen Victoria.

source: The Innocence of Kaiser Wilhelm by Christina Croft

photos: Victoria, Princess Royal, now Princess Frederich of Prussia holding the newborn Prince Wilhelm, later Kaiser Wilhelm II. Queen Victoria holding her grandson, Wilhelm and the final is a drawing of him made by her.

#i felt the need to post this#he was such an adorable baby lol#cutie pie#kaiser wilhelm ii#wilhelm ii#monarchy#german monarchy#imperial germany#germany#german empire#victoria princess royal#empress frederich#queen victoria#emperor frederick iii#british monarchy#brf#british royal family#royalty#royal family#german royal family#german royalty#great britain

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

axis powers leaders as cats 🐱

⚠️ the art was made for art practise only, not to propagate any political views or ideology.

#hirohito#emperor hirohito#austrian painter#ww2#italy#germany#japan#abyssinian cat#german rex#japanese bobtail#ww2 art#my art#my stuff

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trier - ancient Roman capital in the Mid West of Germany

youtube

#travel#youtube#wanderlust#wonderjourneys#tourism#touristdestination#germany#deutschland#trier#hidden gems#hiddengem#allemagne#roman empire#Rome#emperor constantine#porta nigra#kurfüstliches palais#amphitheater#moselle#eifel#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Misérables is written about three or four different time periods depending on the given chapter and the level on which you're reading it (literally versus historically versus philosophically, etc.). I don't think I appreciated until episode 7.13 of Mike Duncan's Revolutions podcast when he broke down how intensely all of the political factions involved in the 1848 revolutions were influenced by their opinions of the French Revolution, however, how much Les Mis talks about 1848.

I'm gonna be making a post later with a theory about Hugo's characters and structure they pertain to this history and these factions and most especially Cosette's future, but in the meantime, I've transcribed from around 13:10 to nearly the end of the episode so that you all can also appreciate how many levels were involved and have it in writing to refer to and research as you like, because I think it also summarizes pretty well the non-Bonapartist political forces in play at any point in the bricc.

(I also cannot recommend this podcast highly enough for jumping into not just the world of French Revolutions but also Western Revolutions in general.)

So at one end of the spectrum, we have those who looked back at the French Revolution with nothing but horror and disgust and who believed that above all and no matter what the cost, Europe must be kept free of the menace of revolution. But this category of anti-revolutionaries divided up into three broad groups who agreed on practically nothing but the fact that revolution was abhorrent.

First and most obviously, we had the conservative absolutists who returned to power after the Congress of Vienna. The chief leading light of this group was Metternich, and the spectre of the French Revolution haunted no man so much as Metternich. Men like Metternich were so opposed to revolution that they were even opposed to reform. King Louis XVI had invited reform in 1789, and look what had happened to him. So across Europe in 1848 there were conservative writers and members of the clergy and major landowners who believed that you could not even let three guys sit down for a drink or they'd start plotting revolution. You certainly couldn't have a free press. You had to be stubborn, unfair, and ruthless. It was simply too dangerous to be anything less. And this extended to things even as seemingly banal as allowing a kingdom to have a nominal constitution, because in the conservative mind, once you granted the premise that rights came up from the people, rather than down from God through the king, you could just kiss the whole thing goodbye. These conservatives still pined for the days before 1789, and they hated the memory of even the most moderate of French revolutionaries, whose seemingly innocent and earnest appeals for reform had simply been the thin end of the wedge.

But absolutist conservatives were not the only ones who recoiled at the memory of the French Revolution and who wanted to do everything in their power from ever letting it happen again. So this second group of anti-revolutionaries were constitutional liberals who worshiped the rule of law and for whom revolution was anathema to everything they held dear. In France, we would put both Louis Philippe and François Guizot into this category, even if they had oh-so-ironically come to power thanks to the July Revolution [of 1830]. Both men admired the principles that had animated the men of 1789 but who had nonetheless concluded, no less than Metternich, that acquiescing to reform was only the beginning of a very slippery slope. Guizot himself had written a history of France and believed that the king's concessions in the early days of the Estates-General had led directly to the Reign of Terror — and remember, Guizot's father had perished in the Terror, as had King Louis Philippe's [Louis Philippe II, Philippe Égalité]. By the mid-1840s, both men had become stubbornly convinced that everything that needed to be achieved had been achieved and that any further reform would invite that slip into radicalism and the return of Madame la Guillotine. This kind of thinking could also be detected in the minds of rulers over in [modern-day] Germany, where we've discussed that there were these constitutional regimes — Ludwig in Bavaria, Leopold of Baden, and Frederick Augustus in Saxony. Those constitutions existed more as a stopper to prevent revolution than any kind of liberal expressionism.

Finally, there was a third group that cringed at the idea of the French Revolution but who drew the opposite conclusion from Guizot and Metternich: where Guizot and Metternich thought that reform was an invitation to revolution, they felt that reform was a necessary release valve to prevent revolution. So in this category you would find Odilon Barrot and the dynastic left in France who wanted to save the monarchy by reforming the monarchy. You would also find in here a guy like Alexis de Tocqueville, who would go on to write his own book on the French Revolution where he would argue that all of the quote-unquote “gains” of the French Revolution had already started under the Ancien Régime and that basically you didn’t need revolution to change society, you just needed continuous, gradual improvement. We’ve also discussed so far two massively influential reformers in [modern-day] Italy and Hungary who fit this same basic mold. In Italy, we talked about the Count of Cavour in episode 7.09, and in episode 7.08 I introduced István Széchenyi. Both of these guys have broad, sweeping visions for the futures of their respective countries. They believed in liberal constitutional government, economic modernization and social improvement, they simply did not believe revolution was the means of achieving their ends; in fact, this was the very lesson they had drawn from the French Revolution, that the ends had been just, but the means counterproductive. The attempt to cram a century’s worth of work into a single year had not just had disastrous consequences, but they had upset the whole project of reform. I would also throw into this group of anti-revolutionary reformers all of the Austrian liberals in Vienna, who we also talked about in episode 7.08. They believed that the stubborn brittleness of Metternich’s government was inviting a revolutionary upheaval that could be headed off by intelligent and necessary reform.

So those are the guys who desperately wanted to avoid another French Revolution, who instantly shuddered at the idea of ever having something like that happen again. But is that how everyone felt? Oh my goodness, no. There were those who had picked up the thesis of Adolphe Thiers and believed that the revolution of 1789 had been a good thing, a project launched for noble reasons and in fact launched because the existing regime was simply too stubborn to change without revolutionary energy. In this telling, men like Lafayette and Mirabeau were heroes to be emulated while you kept on constant guard against villains like Robespierre and Saint-Just. As you can imagine, this was a very attractive thesis among liberals in Germany and the Austrian empire who saw their own situation as analogous to the Ancien Régime of 1789. Their kingdoms were reeling from an economic crisis, their governments were financially shaky, their natural rights were trampled on by tyrants. So the French Revolutionary project that unfolded between 1789 and 1792 was absolutely a model to be emulated. Bring the liberal, educated intellectuals of the country together and force the kings to grant them a constitution and to guarantee basic civil rights. If they were going to be denied a constitutional place in government, if their local assemblies were going to be neutered, if they were not allowed to vote, if the government was unresponsive, then it was perfectly acceptable to look to 1789 and say, “Yes, we want that too. A moment when men of good will and conscience join together to define the rights of man and the citizen.” Now of course, these neo-1789ers knew the lesson of history well, and they knew that they would need to guard against the villains of 1792, but they did not believe that the Reign of Terror was necessarily inevitable. It had simply happened that way in France thanks to a variety of coincidences, mistakes, and bad luck, so liberals across Europe believed that they could forge constitutional governments that defined civil rights and popular sovereignty without falling prey to the Reign of Terror. Thus, the spectre of the French Revolution would loom very large indeed in the minds of these liberal revolutionaries as the course of 1848 rapidly progressed faster than they could keep up with. As we will see, they will all hit a moment of truth where they have to decide whether to keep pushing and join with more radical forces or quit the whole project, reconcile with the old conservative order, and fight against those radical forces that might lead to the new Reign of Terror.

But there were also those who rejected this whole contrived moralizing of the “good” revolution of 1789 and the “bad” revolution of 1792. They did not recoil from the insurrection of August the 10th, the First French Republic, or the Jacobin Committee of Public Safety. They idolized not the buffoon Lafayette and hypocritical traitor Mirabeau, but rather, the steely resolve of men like Danton and Robespierre and Saint-Just and Marat. These had been men who saw the tyrants of Europe for what they were and knew that one must stand up when the going got tough, not go hide in the corner. These more radical republicans further believed that there was just as much injustice perpetrated by comfortable liberals as conservative absolutists, so they saw the Revolution of 1789 as merely the precursor for the much more important, much more glorious, and much more necessary Revolution of 1792. So though they were enemies of each other, these radicals actually agreed with Metternich that reform really was just the thin edge of the wedge, that it would lead to a greater revolution that would overthrow the despotic monarchies of Europe. In their minds, the widespread slandering of the First French Republic and even the portrayal of the Reign of Terror as the most terrible crime in the history of the world was the nefarious propaganda of the comfortable classes, whether of conservative or liberal stripe. Their propaganda emphasized the dramatic horror of the guillotine in order to cover up the horrors the common people of Europe lived with every day, and the best summation of this argument actually comes from A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Mark Twain.

Now the book wasn’t published until 1889, but in it, Twain writes a passage that would have had a lot of radicals nodding their heads in 1848. He wrote, “There were two reigns of terror, if we would but remember and consider it. The one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood. The one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years. The one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons; the other, upon a hundred million. But our shudders are all for the horrors of the minor terror, the momentary terror so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of the swift ax compared with lifelong death from cold, hunger, insult, cruelty, and heartbreak? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief terror, which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over. But all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real terror, that unspeakably bitter and awful terror, which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves.”

(Sounds an awful lot like like a certain conversation our favorite bishop has with a certain conventionist, no?)

Now granted, I don’t think many of these radicals were actively pursuing a new Reign of Terror, but they were also not planning to settle for a constitutional monarchy bought by and for the richest families of their country. And as we’ve already seen in France, these guys were not going to let the blood of patriots be spilled simply so they could swap one Bourbon for another and give another hundred thousand bankers and industrialists the right to vote. What in that represented the nation? Where in that were the people? Where was liberty leading the people? Oh right, that painting was locked now in the attic so it did not offend the forces of order. In Italy, these radical republican forces who celebrated 1792 rallied around Giuseppe Mazzini and later Garibaldi; in Hungary they would rally around Lajos Kossuth, and when I get back from the book tour, I will introduce you to the radical leaders in Germany, who would not be satisfied by the mere token reforms promised by men who celebrated 1789 but feared 1792, men like Friedrich Hecker, Robert Blum, and Gustav Struve. Everywhere, they would find their support not solely in the salons and cafés but among artisans and workers and students. Those who would mount the barricades not just for the right to publish an article or to mildly criticize the government or the right to vote if you made a gargantuan amount of money: they fought to topple the king and to bring power to the people — all of the people.

So, so far we have men who idolize the conservatives of 1788, men who idolize the liberal nobles of 1789, and men who idolize the Jacobin republicans of 1792. Well, there was also in 1848 also [sic] now emerging a small clique of men for whom even 1792 was not enough. These guys believed that 1789 had been merely a step to 1792, but also believed that 1792 was simply a step to something greater. So where did these guys look? That’s right: they looked to 1796. “1796?” you say. “ What are you talking about? The Directory? Surely not. Nobody says, ‘Ah, yes, the good old days of the French Directory, let’s definitely go back to that.’” And no, of course I’m not talking about the directory, I’m talking about Gracchus Babeuf and the Conspiracy of Equals. With the small but ever-growing, increasingly influential spirit of socialism and communism beginning to take root, men like Louis Blanc and Karl Marx looked to Babeuf and his gang as the first example of what the force of history was aiming to make of humanity. Communities and nations that shared not just political rights but the wealth of the nation. How indeed are you going to sit back and say, “Ah, yes, the declaration of the rights of man and the citizen, and one citizen should have one vote,” and then call it a day when so few had so much and so many had so little? The vote was nothing to an entire family — dad, mom, children, who were all stuck working eighteen hours a day for starvation wages. It was thus not the spirit of 1789 or the spirit of ‘92 that moved them, but the spirit of 1796; and it was not the name Robespierre that got their hearts thumping, but rather Babeuf. Babeuf had been among the very first of the socialist revolutionaries who had not stopped short at merely answering the political question, but who wanted to answer the social question as well. And as we’ll see as we move further down the road on 1848, that the memory of Gracchus Babeuf was not simply a matter of picking some obscure hero out of the historical record: there was actually a direct line of revolutionary succession, because one of Babeuf’s fellow conspirators in the Conspiracy of Equals was an Italian revolutionary socialist named Phillipe Buonarroti [Filippo Buonarroti]. Buonarroti was in prison but later released and would then go onto a long and active career inside the revolutionary secret societies that sprang up after the Congress of Vienna, and we’re gonna talk more about the role that Buonarroti played in kindling and spreading this revolutionary socialism, but for his small cadre of disciples, the revolutions of 1848 would be a chance not to complete the work of Lafayette in 1789 or Robespierre in 1792, but the work of Babeuf in 1796.

#shitposting @ me#revolutions podcast#les mis#1848 revolutions#yes that's plural revolutions were breaking out fucking everywhere#Christ this took forever to transcribe and link#but also I found it to be such a profoundly helpful summary that I really wanted to make it available to everyone#although I was reminded of exactly how annoyed I was when I first discovered that Mr. Duncan doesn't even type out the names#much less release transcripts of his episodes#Sir I Know You Have Them#You Read From Them For Every Episode It Is Scripted#I Can't Remember Names Without Seeing Them Written#SIR#Italy and Germany didn't exist yet but they sure wanted to#Elisabeth of musical fame was about to make a big splash#the Austrian Empire was crumbling#and France was doing as France does ig#new emperor new me#England managed to avoid this whole mess#which is how in this our Lord's year 2022 they still have a monarchy#(for now)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon dismounting with an injured foot at Regensburg, aided by the Surgeon, Yvan, 23 April, 1809

by Claude Gautherot

#napoléon#napoleon#bonaparte#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#art#battle of ratisbon#battle of regensburg#napoleonic wars#roustam raza#claude gautherot#pierre gautherot#pierre claude gautherot#dezydery chłapowski#alexandre urbain yvan#france#germany#history#french empire#austrian empire#holy roman empire#europe#european#french#regensburg#napoleonic#napoleon i#emperor#empire#bavaria

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

German Emperor in Wiesbaden, Hesse, Germany

German vintage postcard, mailed in 1905 to Belgium

#vintage#tarjeta#briefkaart#postcard#wiesbaden#germany#photography#hesse#1905#postal#carte postale#german#sepia#ephemera#historic#emperor#ansichtskarte#belgium#postkarte#postkaart#mailed#photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the Memoirs of Heinrich Heine: Heine’s memories of the time he saw Napoleon in person

The Emperor! The Emperor! The Great Emperor! When I think of the Great Emperor then all is summer green and golden in my thoughts; a long avenue of limes blooms forth into my vision, and in the bowers of their branches sit singing nightingales: a waterfall roars, flowers stand in round beds and dreamily nod their lovely heads—and I was in wonderful nearness to it all. The painted tulips greeted me with beggarly pride and condescension; the nerve-sick lilies nodded tender and woe-begone; the drunken red roses greeted me laughing from afar, the night-violets sighed—I was not yet acquainted with the myrtles and laurels, for they lured not with glowing blossoms, but I was on particularly good terms with the mignonette, with whom I now stand so ill—I am speaking of the palace garden at Düsseldorf, where often I lay on the turf and listened eagerly while Monsieur Le Grand told me of the warlike deeds of the great Emperor and, as he told, beat out the marches that had been drummed during the doing of those deeds, so that I saw and heard everything vividly. Monsieur Le Grand drummed so that he well-nigh broke the drum of my ear. . . .

But what it was to me when I saw him, I myself, with thrice blessed eyes, his very self. Hosannah! The Emperor.

It was in the avenue of the Palace garden at Düsseldorf. As I thrust my way through the throng; I thought of the deeds and the battles which Monsieur Le Grand had drummed to me, and my heart beat the march of the General—and yet at the same time I thought of the police order prohibiting riding through the avenue, penalty five shillings—and the Emperor with his suite rode down the middle of the avenue, and the scared trees bowed as he passed, and the sunbeams trembled in fear and curiosity through the green leaves, and in the blue heavens there swam visibly a golden star. The Emperor was wearing his modest green uniform and his little cocked hat known the world over.

He was riding a little white horse that paced so calmly, so proudly, so securely, and with such an air. . . Listlessly sat the Emperor, almost loosely, and one hand held high the rein, and the other tapped gently on the neck of the little horse. . . The Emperor rode calmly down the middle of the avenue. No agent of the police opposed him; behind him proudly rode his followers on foaming steeds, and they were laden with gold and adornments; the drums rattled, the trumpets blared; near me Aloysius the Fool threaded his way and babbled the names of the Generals; not far off sottish Gumpertz bellowed, and with a thousand thousand voices the people cried: “Long live the Emperor!”

Source: Heinrich Heine's Memoirs, From His Works, Letters, and Conversations; Volume 1

#‘When I think of the Great Emperor then all is summer green and golden in my thoughts’ 😭😭😭😭#Heinrich Heine#Heine#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#19th century#napoleon bonaparte#1800s#napoleon#french empire#france#history#Germany#german literature#romantic#romanticism#german romanticism#french revolution#napoleonic wars#confederation of the Rhine#Düsseldorf

18 notes

·

View notes