#Fox and hound

Text

I would like to made Pirates of Caribbean AU starring Open Season, Monster House and Luca.

It's called the Animals of America

Elliott the deer: Jack Sparrow

Boog the bear: Joshamee Gibbs

Luca Paguro: Will Turner

Giulia Marcovaldo: Elizabeth Swann

Ivan the deer: Hector Barbossa

McSquizzy the squirrel and Mr. Weenie the Dog dachshund: Pintel and Ragetti

Tank the penguin: Bo'sun

Deni the mallard duck: Cotton

Coraline Jones: Anamaria

Horace Nebbercracker: Davy Jones

Constance Nebbercracker: Tia Dalma

Massimo Marcovaldo: Governor Weatherby Swann

Lorenzo Paguro: Bill Turner

Giselle the deer: Angelica Teach

Grizzly Bear(From Fox and Hound): Barbanera

Todd the fox: Philip Swift

Vixey the vixen: Serena

Ercole Visconti: Norrington

I taken a few characters from Fox and Hound to play Philip Swift, Serena and Barbanera

You know? Open Season and Monster House are two movies that release in 2006 the year that Jacob Tremblay was Born, fifteen years before he voice Luca. Fox and Hound was release in 1981 and twenty-five years later arrives the midquel and i choose Todd, Vixey and the Grizzly Bear to play Philip Swift, Serena and Barbanera because the Grizzly Bear captures Todd, because he was raise by Widow Tweed, and he force him to attire Vixey with the Fox call and to capture her and to search the waterfall of Youth. Fortunatly Elliot with the help of his formerly rival Ivan and his friend Boog save Giselle using the waterfall of Youth while the Grizzly Bear gets killed and Todd and Vixey can live in peace.

In carriage Chase from Pirates of Caribbean 4, i was thought to use Dixie, from Fox and Hound, playing the Older lady in Aqua dress that Jack Sparrow stealing her earring.

Luca and Giulia were perfect to play Will and Elizabeth and because Luca when he gets wet he becomed a Sea Monster Just like Will and the ship of his father.

#open season#luca#pirates of caribbean au#monster house#elliot the deer#boog the bear#ivan the deer#luca paguro#giulia marcovaldo#horace nebbercracker#constante nebbercracker#giselle the deer#fox and hound#grizzly bear#todd the fox#vixey the fox#lorenzo paguro

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1BLE

The Collective has been growing. Not everyone is a part of it, because the Company was a chimera that not even one man’s word could control, and there had been threat of retribution by some of the investors and shareholders. Some of the miners were scared enough to stay with the status quo, to ask not to be part of what Silco was doing. But the breaks and adjustments to shifts were introduced for everyone, not just for those who were part of the Collective. That, Silco assured them, was the whole point of the Collective: better circumstances for all, and to prove that they would be stronger together, that life would be better arm-in-arm.

It also hadn’t been Silco’s idea to start pooling funds for new projects, but he encouraged the idea once he heard it at the meeting. There was so much that needed to be done in the mines, yes, but the Collective was made up of people. People had needs.

There were plenty of miners who couldn’t work: the injured, the sick, those with inherited conditions, and so on. Sometimes these people were compensated by the Company, but more often they were not. These people still needed to eat; the Collective began to see to it that no-one would be without a meal, or without work. And soon more ideas were offered at the meetings: these folk who could not work in the mines would not be out of work entirely. They could teach mathematics and language to the children who weren’t needed in the mines. Others could clean and maintain the masks and mining equipment, and share the techniques needed for such care and maintenance. There could be classes for literacy and mathematics, there could be classes for cooking and clothing repair and other basic needs, there could be classes for music and storytelling. And, one of the most eagerly-embraced ideas of all, there could be changes made at the mines to make the newly-implemented breaks a little more comfortable.

The Collective Canteen had been built with scrap and rubble, broken carts and rusted beams, squared-off blocks of discarded mine stone, and draped sheets held in place with rail spikes. It squatted near the mine entrance, puffing smoke from jerry-rigged chimneys. It was so beautiful in its ramshackle ugliness, because it had been made by a community with love.

Three months after its opening, Silco lifts the canvas doorway and looks inside with a small proud smile. The ovens, the benches, the shelf of battered pots and pans and implements, the jars of donated grains and spices… it wasn’t much, but all of it was the Collective’s. This hadn’t been his idea: look what the people had come up with on their own, as they pushed for things to be better, as the spark was shared between them. Those who couldn’t work in the mines took shifts here, making meals that children would deliver below to the crews. People could have proper hot meal to fill the belly, not just a smuggled crust of bread in a coat pocket to be eaten while the foreman wasn’t watching, like they used to. The Collective was growing. People were taking care of each other. Things were getting better.

“There’s coffee on the stove.” A voice interrupts Silco’s thoughts. The Canteen saw workers coming and going all the time, each taking their turn with service, but Maryam had been here the longest. An arm injury had brought her here, but a pregnancy had been a good-enough reason for her to ask if she could stay. She was too far along to swing a pickaxe, but she was organised, and trusted, and happy to help.

“I can smell it,” Silco says, letting the canvas fall closed behind him. “I’ve been thinking about a cup since my shift ended.”

Maryam waves her pen vaguely at the stewpot behind her, a huge battered thing, set on top of a broken and overturned minecart. “Then help yourself.” She is busy with tallying the day’s takings, flicking beads on an abacus and counting the thin tin and copper coins in front of her. Not everyone could pay, but those who did made it easier to fill the larder for the rest. And when everyone was fed, everyone benefited.

Silco grabs a scuffed enamel cup from the rack and slips behind the counter. The fire that had been burning under the minecart is down to its last coals, and the dark liquid in the stewpot isn’t steaming. Still, coffee is coffee. He dips his mug to fill it, and takes a quick thirsty gulp of the bitter brew.

“You know Kassandra?” Maryam asks. She glances up at Silco joins her at the counter. “In Work Crew Jussi?”

Silco thinks for a second, then nods. “Yes. Married Tyr last season?”

“That’s her.” She nods, sweeping a small stack of coins to one side. “She has a cousin in Production, in Bergen proper, and might be able to get something to add to the stews. She says the cousin can get her a few sacks of leftovers. Might even be able to make it regular if we’re good to them.”

Silco nods thoughtfully as he sips the coffee. “It won’t be cheap,” he notes, “Even with a family discount.”

Maryam shrugs, her mouth pulling in a wry smile. “Maybe we should invite Production into the Collective.”

He laughs, dryly, incredulous. Why would Production need a Collective? The workers in the city no doubt have protections and wages far better than those who perform hard labour on the outskirts. “We’re doing very well as it is. Better than expected and in such a short period of time.”

“Mmm,” she hums, tapping her pen on the counter. “But we can do better than leftovers and grocery donations from home kitchens.”

“We can?” Silco asks, mildly. When the woman just grins, he laughs and nods to her in salute. “You have an idea. You’re ambitious.” He’s pleased. He so loves seeing the way ideas and hope bloom these days.

“I’ve been here long enough that this place is my baby.” Maryam looks around, proudly, then sets her hand on her belly. “I’m going to have this child here, I’ve decided. Spill blood and bring life out on this hard-packed earth.”

Silco raises his mug in a silent toast. He recognises the words having some kind of rite quality to them. He had never learned his parents’ religion, and had no community outside of the mines. But there are those who toast, and so it follows that this seems like a statement worth toasting; there is power to it, and more the power to her for it. More power to all of them.

“I do have an idea,” Maryam continues, as she finishes her count and swipes the coins into an old lunchbox. “It’s not one that’s gonna take off anytime soon. But there’s plenty of tunnels where the ore’s run dry and the coal’s chipped out. Ones near the vents, so air’s not sour. What if we made use of some of that dead space?”

Silco frowns in thought, nodding as he considers how much of mines gets abandoned or buried whenever it no longer produces. “In what way?”

“Well.” Maryam folds her hands over her belly, smiling, “What if we made a garden? A few boxes of shit and soil, and we could start growing mushrooms.”

Mushrooms. Silco’s mouth involuntarily waters; he looks at the woman in wide-eyed admiration.

“Collective-grown crops for the Collective canteen,” the woman smiles serenely. “And who knows? Maybe we could even start ranching rats.”

“My gods. We’ll eat like kings.”

Maryam laughs. “I s’pose I’m cleared to bring it up at the next meeting?”

“You don’t need my permission t—” He freezes, hearing something outside.

“Well, I thought I’d—”

Glass shatters. Fire blooms against the wall of the canteen. Maryam screams. Silco dives for her, shielding her as best he can with his scrawny frame, hauling her to her feet and moving at staggered, stumbling swiftness as they make for the canvas wall, for outside.

He hears it louder now, the sound of footsteps and angry voices and then, as he and Maryam push out of the flames and smoke, he sees them. Strangers, illuminated by torches and glow-tubes and moonshine-bottle grenades.

Another one of those grenades hits the side of the canteen, and the strangers howl and cheer. Maryam screams again, this time in outrage and fury. Miners still around after their shift are running to sound the alarm, to gather pails of dirt for to smother the fire, and to come to the aid of Maryam.

Silco stares at the fires. His eyes are wide, and all he can see is the canteen up in flames. Everything burns, and he feels cold.

Maryam is still screaming, pulling herself out of the teenager’s arms to address the strangers with curse and fury, but she doesn’t get far. She staggers, and falls, clutching her belly. One of the strangers moves to stand over her, arm raised as though to strike her.

Silco moves, then, whip-fast, charging forward. He doesn’t have the strength to tackle the man to the ground, but he has a pretty knife he carries with him always. A few rapid jabs are enough to drive the man back, but now— Silco grits his teeth and braces himself, standing between the pregnant woman and the angry mob. His hand grips the knife in a tight fist, trying to keep from shaking.

He can see them now, this mob. Rough and filthy and furious, armed with pick and shovel, men and women with bared teeth and fury in their faces. He realises with an odd jolt that he is staring down a group of miners. Strangers, yes, but miners.

“What in the good hells are you doing?” He doesn’t have a voice that carries, not with his lungs burned out, but they’re not watching the canteen burn anymore. They’re watching him, and they hate him, so they hear him. “Why are you doing this?!”

They didn’t come here to talk. They came with fire and weapons and hate. They cuss him out, and call him bastard, and say he and all his kind deserve this. Silco scans their faces, and sees the anger he’s familiar with, the kind of anger that once had him pinned against a tunnel wall with a pick at his throat. They have the same fury he did: he’d thrown dynamite into a tenement with that anger, and in the same way they’ve made their grenades to burn down this canteen.

They’re strangers to him, but they’re miners. They must come from another Company, another part of the mountain. But why are they attacking the Collective? Why are they calling him a bastard?

There’s no time for rhetoric. There’s no air left to speak, because it’s all being used in the fire burning down the canteen. All he can do is hold his ground and protect Maryam, as ash falls down over him and the canteen collapses into charred wood and smoking metal.

Yakob, Maryam’s husband, slam-tackles one of the strangers to the ground, and starts laying in with his fists. He’s not alone; other members of the Collective charge down the hill and throw themselves into the melee. Silco glances to Maryam – seeing her well, but there’s despair in her face as she watches the Canteen burn – before he snarls and charges forward to join the fight, to protect what’s theirs.

It’s a brawl of blood and fists and ash and the gleam of Silco’s knife, under a grey fresh-smoke sky.

---

“Right, that’s the bandages done. Let’s see that eye of yours again,” Vander says, peering in.

Silco obediently lifts the bag of ice chips off his face, squinting with the good side of his face.

The messy-haired youth gives a low impressed whistle. “Swelling’s down, but you’re gonna have a hell of a shiner, Sil.”

“I didn’t even know my face could bruise,” Silco admits, putting the sodden icebag back against the right side of his face. “I thought the gas-paralysis prevented that.”

Vander shakes his head, then resumes his close scrutiny of Silco’s battered hand. For a man with large hands, he is being very careful, very gentle, and very thorough. When he presses against Silco’s knuckles, Silco winces at the pain, and Vander eases his touch immediately. “Describe the pain there, Sil.”

“Uh. Ouch?”

“Sharp, stabbing, lingering?”

“Sharp, I guess? Fades to an ache?”

Vander massages around the ache, then gives a small grunt of relief. “Nothing broken, then. Good t’know.”

Silco blinks with his good eye, his lips pursing in the best smile his face would allow. “And you know this how, exactly?”

Vander opens his mouth to answer. But his father answers first, busy as he is in the kitchen.

“He were apprenticed as a doctor’s boy,” Carlisle Vander grizzles, slamming a cleaver into root vegetables with more aggression than they deserved. “Five years of trainin’ an’ workin’. Waste of a good education, ‘coz he turned tail an’ ran soon as the work got too tough.”

Vander’s face creases in exasperation. “Dad.” It was a warning, a plea, an attempt to interrupt what was clearly an argument hashed and rehashed on-and-off for years.

“It was your ticket to a better life,” the older man throws a scowl over his shoulder. “Did we scrimp an’ save for months to get you the joinin’ fee? That we did!”

“Dad.” Vander gives Silco a look of mild apology. He hasn’t let go of Silco’s hand, and still circles his thumbs around the shape of Silco’s knuckles.

Silco, though, lowers the bag of ice and stares at the messy-haired youth. “You were a doctor?”

“Just an apprentice,” Vander mutters.

“Couldn’t handle it,” his father offers, scathingly.

“Dad, enough. I already tol’ you what it was like.” His accent always became more pronounced when he was at home. “It weren’t a life fer me.”

“Imagine what you coulda been,” Carlisle tossed the rough-chopped vegetables into the pot, where they hissed in the oil in protest. “Coulda had a proper future.”

“Weren’t the future I wanted, Dad, so drop it.” He pauses, and looks at Silco’s hand, and face, and the bandages he’s just finished binding, and a flush of colour rises in his cheeks. “I know enough, learned enough. Didn’t need more. We’ve been over this.”

“You weren’t born a doctor?” Silco feels like he’s missing a significant piece of context. “And you just… you left? You can do that?”

“Well, yeah.” Vander says, managing a lop-sided smile.

“Not everyone’s born into a profession like you, lad,” Carlisle offers, shrugging. “Not everyone in Zaun’s born t’a Company. Some gotta buy their way into somethin’ new, or they pick up what they can, where they can. S’why we’re runnin’ a pawn shop.”

Silco feels the ice in his hand and the ache in his hands and face, and is suddenly conscious of how big the world is when you’re not pinched between stone and darkness. “People can choose where they work.” It’s a revelation. It makes him feel small, and ill, and in the same way he felt when he stood on the edge of the Ironspikes and looked south to see the world unfurled vast before him. A world within view but just out of reach.

“Aye,” Carlisle mutters, giving his son one more dark look, though now at least it is tempered with a grudging acceptance. “They can.”

Vander pulls a face at his father, then gently lets go of Silco’s hand. “You’re stayin’ the night again, Sil?”

“Maybe. I don’t know.” Silco still has too much adrenaline in his system, after the fight, after dousing the fire, after getting clocked in the face, after having his hand and face touched with such care by Vander. “I don’t want to cause you any trouble.”

Carlisle grunts. “If your Company wanted t’fuck us over, lad, they’d’ve done so already. Not like you two’ve been subtle about your sneaking off.”

“Dad!” Vander buries his face in his hands.

“Dinner’s in the pot an’ cookin’ up.” Carlisle ignores his son and gestures the ladle in a vaguely-threatening way in Silco’s direction. “You’re stayin’ t’eat, but after that I don’t give a rat’s arse what you do with your time or where you lay your head. Get me?”

“Thankyou, Mister Vander,” Silco says, politely, lips quirking as he fights not to smile. He’s familiar with the old man’s surly affection now, and hears the invitation to stay the night for what it is. “I appreciate it.”

The old man grunts, then gets back to work.

“‘Mister Vander’,” the younger mocks, under his breath.

Silco smirks a little. “You’re the one who doesn’t like being called by your first name,” he points out, in the same whispered tone. “Warwick.” Pronounced ‘worrick’; Carlisle, too, was not pronounced how it was spelled, being ‘car-lyl’. It was a habit of Middletongue to pick up and discard rules of language as it saw fit, especially when it came to names.

Vander the Younger flushes a slight pink. “Shut up.”

“Make me.”

Vander looks like he plans on making Silco shut up, with his eyes dropping to Silco’s lips and a grin starting to form. But then Carlisle calls for his son to set the table, so the young former-and-not-currently-a-doctor Vander sighs and gets to his feet and wanders across the room to help.

Silco puts the ice back against his face. He thinks about being born a miner. He thinks about the miner who gave him this black eye. He thinks about the fire that burned down the Canteen, and the view beyond the borders, and his jaw sets with renewed determination.

---

His cigarette is burned almost all the way through, but he’s barely noticed. He and a few others from the Collective have been watching this other mining site for the better part of two hours now, noting the differences between the Company that runs this place and the one that owns where the Collective toils. The conditions are as different as night and day. Silco nurses his anger.

The whistle has blown to signal the end of shift, but the emergence of miners from below takes agonising hours. Company agents and security check each miner for ore or shale they might be trying to smuggle out. Equipment is collected and scrutinised. Each shuffling, miserable miner is given their scrip and made to depart the property. It’s pitch black, but for the floodlights trained in the ragged folk shuffling out from under the earth.

“Looks like a prison camp,” Gesso hisses softly. Silco agrees, but says nothing. He just finishes his cigarette.

Most miners shuffle off towards the Company-owned tenements. But there’s many more who make their way to the mazelike slump of tents and shacks that pock the mountainside, homes built between the air-pumps and shale-vents. There’s a larger building, sitting humped like a tumour at the start of the path, where signs proclaim in symbol and rough-painted sign of food and drink available. It seems busy. Crowded. Yet it lacks the usual jollity of a tavern. It is the first target for so many, including the crowd the Collective have been observing.

Silco drops his cigarette and grinds it out under his shoe. “Let’s go.”

As expected, he finds many familiar faces. But before they can give him another black eye, he starts to ask them questions and drawing comparisons between this mine and the one they attacked last night. Those who aren’t so deep in their cups can give what answers they can. The hostility remains between these miners and the handful of Collective folk. But Silco knows how to talk. He pulls at their pain, and shows them a spark. Money is a good way to get people to pay attention. But power? Power is a good way to get people to listen.

“Your Company bleeds you, your Company denies you your pay and your freedom, and your Company tells you we are to blame… and you believed that?” He meets the gaze of the man who slugged him across the face, and spreads both palms out, a query to make every one of them think, before he addresses the tavern interior. “The Company needs you. But they need you to be their wretched servants. They can’t ever let you think or fight for yourselves. They’ll tell you it’s for the sake of the business, or necessary for the bottom line. But really, you know what they want. They want you to be numb and obedient and to say ‘thank you’ for every crumb.” He cocks his head, and seeks out the gazes of those who seem the most infuriated. “Don’t you think you deserve better? We did. That’s why we formed the Collective.”

It’s morning by the time Silco and the others return, after hours of sharing their stories and explaining just what kind of steps they took. It’s dangerous, of course it is, to take the steps that the Collective has, to take that risk and challenge the hand that squeezes your throat. But it’s something to think about. So they give these miners time to think.

Over the next few weeks, there are strangers that join the meetings at the Collective, listening, questioning, cultivating their own sparks. And by the time the Collective Canteen has been rebuilt, the next Company over is starting to feel the tables turn, and understands that their plan – to get the miners to squabble between themselves – has backfired in the worst possible way. For the Company, at least.

---

The map is several conflicts out of date, but the shapes of most borders and landmarks is at least recognisable enough for his needs. Silco traces his fingers around the Ironspikes Mountains, the northeast-to-southwest border that encircles Zaun, then further still in an unbroken curve up to the northwest where Piltover claims. Past these mountains stretch vast plains: the indistinct blur of the Freljord’s snowfields and coasts, the river-crossed forests before the rigid borders of sunny Demacia in the west, the rocky gravel-strewn lands of Noxus to the east, and The Great Barrier, the barbarian-settled mountain range that separated the civilised states from the wildernesses of the Shurima Desert, the Voodoo Lands, Urtistan, Kumungu, the Plague Jungles and the ruins of Icathia. Then far far south, Bandle City, safe from wilderness and conquest by these natural and dangerous barriers, but still able to reach the rest of the world due to their flying machines and their access to the coast. The world committed to paper, and yet not all of it. There was so much more in the details lost to paper, and even more across the sea.

Silco traces his fingers over the map again, this time over the rough sketched lines of the trade routes that connect Zaun to Noxus. A war machine is always hungry for ore and stone. The fruits of Mother Zaun keep the tyrant Darkwill’s hunger keen.

“Zaunite iron,” he murmurs to himself, “Beaten into armour and swords, taken all over the world.” Wherever Darkwill’s desire for conquest took him. South past the mountains, east across the sea, even west and north to Demacia and the Freljord, and further still. The rocks that passed Silco’s hands from the grinder and into the shipping bins could end up rusting and abandoned on some foreign shore. It was fascinating to think about.

He turned back a few pages, leaving the world behind, and looking instead at Zaun. The inaccuracies of the map were now even more obvious, with Zaun being divided simply into six districts. Even the river was the wrong shape: it would be a decade or more before towers and factories and Company rivalries started changing the shape of the city and securing the shape of the land into something more defined, more easy to claim and control. But even now, against the back of the Ironspikes, the district that the Collective first bloomed in was known – then and now – as Bergsen. It had been a big district. Now it was one of the many fragments of the Economic Exclusion Zone. A modern map would no doubt show how many shards the EEZ was in, how many Executives had their hands on territory and were refusing to share.

Silco had grown up thinking the Company was everything. To know that they were merely a fragment of the companies that were owned and fed profit back to the head of the district was … something. To know he was a tiny piece of a tiny business of a tiny corner of one of Zaun’s smaller border towns… it could make a man feel almost insignificant.

Instead, Silco took a pull at his cigarette, and swept his fingertip over the southern curve of the Ironspikes Mountain on the old map, letting his vision blur. There were a lot of mines through these mountains. There were a lot of other businesses, too. And the river started here in these mountains as well, fed by underground springs and snow-melt. The underground tunnels - watched and guarded by the private armies of each district’s Executives - might be the way that trade goods from Zaun got through to Noxus, but all of Zaun’s businesses used the river to bring those goods to the border.

Silco swung the heavy atlas closed and tapped his cigarette into the ashtray. “Vander.”

“Yeah, Sil?”

“Your father used to work Freight, right?”

“Yeah?” The young man’s lips twist in sudden wryness. “What’re you schemin’ this time, Sil?”

Silco hummed thoughtfully. “I’m just thinking about making some new friends.”

“An’ you want some introductions?” Vander sighed, chuckled, shook his head. But bright mischief lit up his face. “Well, I might still know some folks. When do you wanna make the trip?”

Silco stands, flicking the last of the ash off his cigarette and grabbing his coat. “Now. Now seems like a good time.”

#the miners' son#fox and hound#some time back#towers and mines#neatly printed on letterhead#cigar smoke

0 notes

Photo

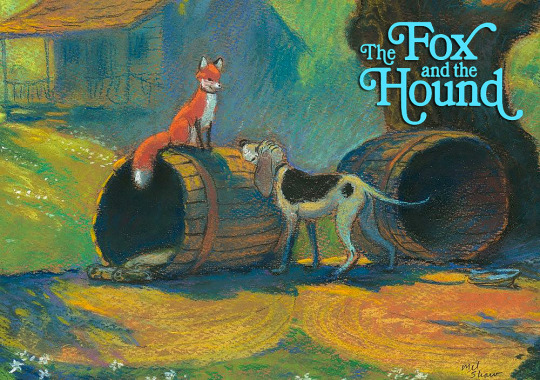

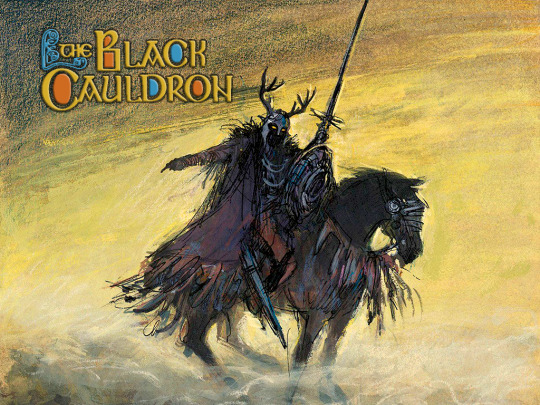

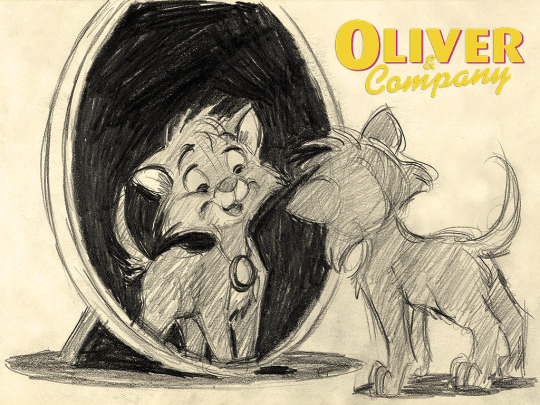

𝙳𝚒𝚜𝚗𝚎𝚢 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚌𝚎𝚙𝚝 𝚊𝚛𝚝Iᴛʜᴇ ʙʀᴏɴᴢᴇ [ᴅᴀʀᴋ] ᴀɢᴇ (1970 - 1988)

#there are many opinions about wether these are two eras but i think it's one that got gradually worse#disney eras#disney#The Bronze Age#The Dark Age#disney concept art#animation art#art#artwork#illustration#mine#disneyedit#visual development#the aristocats#robin hood#the many adventures of winnie the pooh#the rescuers#the fox and the hound#the black cauldron#the great mouse detective#oliver and company#it's not that dark tbh

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

AU in which the chancellor dies in a freak (probably Zillo-beast related) accident. Everyone is attending his funeral and really, the Jedi are trying really hard to mourn but it’s incredibly difficult to when the entirety of the coruscant guard is apparently throwing a mental and spiritual party so loud in the Force Dathomir can feel it.

#text post#hijinks#my writing#star wars#clone wars#tcw#coruscant guard#corrie guard#jedi#star wars au#fix it#sheev palpatine#commander fox#commander thorn#commander thire#commander stone#clone trooper hound#zillo beast

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

After 21 failed, and/or thrown away design attempts, i present the popo 👮🏻♂️🚓

I struggled a lot with this one, and words cannot truly express how much i hate how it turned out, but it is what it is, so moving on lol

You can check out the models from a closer look here

3rd poster in the line, 3 more to go ✨

Clone Force 99

501st

104th

----------------------------------------------------------

taglist: @callsign-denmark @techwrecker @dahscribbler @lightspringrain @dreamsandrosies @brainless-tin-box @thecoffeelorian @luzfeather @burningfieldof-clover @99tech99 @theglitterdark @fangirl-goes-nova

#star wars#star wars fanart#clone wars#clone wars fanart#tcw#tcw fanart#clone troopers#coruscant guard#commander fox#commander thire#commander thorn#sergeant hound#game design#game dev#3d modeling

811 notes

·

View notes

Text

— The Fox and the Hound, 1981

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

do you love the colours of fall?

(requested by anonymous)

#the fox and the hound#the adventures of ichabod and mr. toad#disneyedit#fantasia#melody time#the many adventures of winnie the pooh#bambi#filmedit#filmtvcentral#animationedit#classicfilmsource#*#gifs#film#animation#golden age#wartime era#bronze age#kenn

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

ANIMATED FOXES IN FILM 🦊

Robin Hood in Robin Hood (1973)

Todd & Vixey in The Fox and the Hound (1981)

Mr. & Mrs. Fox in Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

Nick Wilde in Zootopia (2016)

Fink the Fox in The Wild Robot (2024)

#robin hood#the fox and the hound#fantastic mr fox#zootopia#the wild robot#filmedit#fox#filmgifs#animationedit#animationdaily#animationsource#cinemapix#useroptional#pedro pascal#films#*edits#userfanni#i love foxes. if i missed any i dont wanna know.#(is it cheating putting this in the pp tag? HES FINK THE FOX okay justified)

419 notes

·

View notes

Text

SuperbOwl Day!!!!

~We interrupt your regularly scheduled program to bring you coverage of an important competition~

please comment or tag whichever SuperbOwl we forgot

~Thank you, your regular program will resume shortly~

#yen sids poll#non-tournament poll#yen sid comments#superbowl#owl#disney#disney animated movie#disney channel#winnie the pooh#the owl house#the fox and the hound#the sword in the stone#sleeping beauty#alice in wonderland#ducktales#doc mcstuffins#disney animals

573 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amos Slade: No "buts" about it! Miss Sabine Wren has been avoiding her responsibilities long enough. It's high time she married and settled down.

Luigi Mario: (comes out of hiding) Of course, Mr Slade. But we must be patient.

Amos: I am patient! (throws an inkwell)

#amos slade#jack albertson#fox and hound#luigi mario#charlie day#super mario bros#star wars#sabine wren#cinderella au

0 notes

Text

3BLE

There is a work song being sung by every crew. It is not the same song, and every crew keeps a different time, but every crew in the mine is singing. The tunnels ring with echoes. Silco does not sing, not even to keep the pace with his own crew, pushing the carts (full, to the shaft entrance, and then empty again back into the tunnels), but he smiles, and lets himself dare to hope that this is a sign of the coming days.

But Zaun can be cruel to those who hope.

The mine-cart crew push onward, down the spiralling paths, pushing the empty carts before them, down and down to where coal and stone wait in piles to fill them. It’s coming up to late morning, when the foremen - based on talks and agreements with the miners’ collective - will allow the workers and children in the mines a chance to rest, to eat and drink and talk. It was a fierce fight to negotiate these half-hour breaks, but the productivity had been proven. Now, the promise of upcoming rest made the songs louder, made the picks and shovels strike harder into the rock.

Silco locks the empty carts into place, then pauses, head cocked slightly. There were the sound of echoing voices. There were the sound of effort and hard work. There was the new whistling call for the break time. But there was something missing.

Something essential.

He hadn’t noticed, amongst the song and the hard work and the thoughts of what he could accomplish next. But now he cannot help but notice. He cannot help but notice, because there is no mining crew coming to meet them, to load up the raw materials into the carts before they take their break. There are no miners… and there is no sound above the echoes of whistle and song and pickaxe and shovel, all of which are fading.

“Masks!” Silco shouts, his voice a harsh bark in the tunnels. “Masks, now!” Song and discussion between the cart crew die, and confused faces turn his way. Silco is already fumbling with his own rebreather, and as soon as the straps were fastened he screams again, louder. “Masks! Mask up, now!”

Slowly, the others begin to hear it. The silence. The fans are still. The fans that pump in fresh air from the surface, that prevent the buildup of toxic and flammable fumes, are not turning. The silence is deafening, and deadly.

Without the fans, the mines are nothing but an extensive tomb complex. Or, Silco thinks, as the old childhood fear began to stir in him, like the vast cavernous stretches of a hungry creature’s internal organs. Mouths and gullets and stomachs throughout the rock, stirring, ready for a meal.

Silco starts barking urgent orders. There should be a work crew around the next bend, coming to deliver their work to the carts; two of the cart-crew are sent to find them, to get them masked up. Another is sent to the alarm box, further in, to pull the bell and let the tunnels above them know of the danger. Yet another is sent to go and try to find the foremen who were supposed to be stationed here, to find out why they hadn’t sounded the alarm. Silco picks the eight of the cart-crew who had families deeper in to do the dangerous - but necessary - work of going to find them. Deeper in, the gas could be more potent, making it a greater risk that even their masks might fail to protect them. But they are children of the mines, all of them, with scarred lungs and the desperate fear of leaving their loved ones to die in the dark, so while they may be afraid to go, they would be more afraid not to.

“The rest of you, with me.”

Silco takes off running, following the tracks back upwards. Adrenaline flooding his system gives his strides length and speed, and his mind picks over what comes next. Why had the foremen not sounded the alarm yet? Surely they would be invested enough in their own wellbeing to put out the alarm for masks, perhaps even calling to the surface for answers. Unless they weren’t at their posts? Why wouldn’t they be? They worked here, too. There’s no sense or reason in flooding the whole mine with gas. Even if they hated negotiations and breaks and the power the miners were gaining, the foremen worked here too, so there is no sense in turning off the only source of air that feeds the whole mines.

The Company hated the thought of work stopping, and thousands of dead miners would make the work stop most definitively. Even if the foremen sided with the Company, they worked in the mines; unless they abandoned their posts, the foremen had to be here, suffering with the miners, because not even the Company would let them all down. The Company paid excellent lip service as long as they profited; turning off the fans was not a profitable move.

But regardless of how, if the fans were not working, then every second, every breath, brought the whole mine closer to becoming a death-trap. Some of the newly-dug tunnels might have been overwhelmed already. Maybe some of the other miners heard the strange silence, maybe some were masked up. But how many of them were distracted by the work, pushing just a little harder so that they could enjoy their break even more, and had missed that background hum to which they were all accustomed to?

Legs pumping. Eyes stinging. Heart pounding. Silco is a creature of effort, the worry fuelling his run. The elevator had already risen back to the surface, so the sloped tunnels upwards were the only path out, step by step through the dim light and the shadows. And every level they ran, Silco and his three companions heard none of the fans turning.

That shouldn’t be possible. There are eight generators, each of them designed to take the responsibility of a different section of the mines. For them to all fail at once was not possible, bar a district-wide catastrophic power failure.

Run. Silco chews his suspicions into the side of his mouth, and forces himself to keep running. By now, the alarm has been raised, and the siren is echoing through the tunnels, the work songs replacing with cries of alarm and dismay. Others who did not have masks - there aren’t enough provided by the Company for every miner, when they sign in for the day, and not everyone can afford one of their own - join Silco and the cart-crew in their run to the surface, desperate for air, for survival.

He feels himself flagging. His burned lungs can’t sustain him, his body doesn’t have the strength after such a long run. He falls behind, as miners stampede towards daylight. Someone else will make it there before him, someone else can see why everything broke down. Someone else can make it right. It doesn’t always have to be him.

But then the folk of the mines form a wall ahead of him, or even turn around and go back into the tunnels, putting their backs to the stone even as they crane for fresh air, air they did not seem willing to go out to get for themselves. Silco braces one hand against the stone of the walls, wheezing through his mask, feeling dizzy from the sudden exertion in oxygen-poor slopes.

The miner nearest to him looks at him with fear on her bare face. “They have guns,” she says, her voice a rasp from the bad air.

Guns. Silco feels it like a punch in the gut. Someone did this deliberately, someone wanted all of the work crews - every man, woman, child - choking to death in the dark, and they are here to enforce their cruelty with weapons. Who, the foremen, Company men, a rival mine, who? Someone with guns.

“Helvetti.”

The miners are looking at him. They are all looking at him, shaking in the dark from fear or gas-poisoning or anger. They are looking at him, at this young man with fury in his eyes who has inspired them and guided them this far, because they do not know what to do now.

Silco does not know, either. But there are people in the dark who need to breathe. He needs the fans turned back on.

He is afraid to do this. But he is more afraid not to.

Silco pulls off his mask and passes it to the woman who is struggling to breathe. He straightens up, hands clenching into fists. And then he steps forward. He does not need to push through the crowd, because the miners step away for him, peeling away from him like shadows from a lantern.

It takes a moment for his eyes to adjust to the light, so for the first few steps he is walking blind. Even daylight filtered through Zaun’s persistent cloud cover can be too much to those who stay beneath the earth. He blinks away the glare, following the mine-cart tracks to keep his passage in a straight line, taking the time to assess the blurry shapes that have taken formation before the mine. As his sight returns, little by little, he can see some automobiles, a van or two, parked close by, but nothing that speaks of a paramilitary presence. There are guns, yes, and as his eyes focus he sees them casually levelled at him. At least fifteen, maybe twenty of them, in the hands of those who look… clean. Monied mercenaries, guns for hire, tenth day professionals, casual thugs with clean soft hands closed around stocks and triggers. Clean guns in the hand of clean folk.

They have these guns ready, but none of them open fire as Silco steps out into daylight. That must mean there’s someone here who hasn’t called the shots, yet. Or maybe one dirty, scrawny teenager isn’t enough of a threat to waste a bullet on.

He blinks, he focuses. Silco’s eyes pick out the only one in the crowd who doesn’t have a gun. Body language of confidence and control. But as Silco blinks away the last of the glare, he cannot help but feel incredulity creep in. That is who is in charge, really?

They’re a joke. They’ve garbed themselves in studded leather and machine-pressed cotton. They’re sleeveless, showing off ornate geometric tattoos, arm-bands of leather, and muscles an infant would be proud of. They also carry carefully-painted lines of a Shimmer user, the chemical burns and residual glitter accentuating the knuckles of their hands and the cast of their cheekbones. They have a gold ring in their nose and gold pins in their ears, connected by chains to a series of golden studs. Real gold, too; Silco can see where the metal is dented in places.

They’re a kid, somewhere in their teens, but soft in a way a miner’s child never would be. Younger than Silco, even, if the neatness of their teeth are anything to go by.

Silco eyeballs this youngster, then keeps walking. Heading for the fan generators. The security fence is open and there are a cluster of mercenaries around it. He needs to get there, to get the generators running again. There are people in the dark who cannot breathe.

“Oi.”

Silco keeps walking.

“Oi, shit-for-brains, you best stop walkin’ or you’re a dead man.”

Silco steps up onto the track rail, and then over to the other side. Still walking.

“I’m talkin’ to you! Hey!”

By now Silco has come face to face with one of the mercenaries outside the generator gate, who seems decidedly amused by how things are progressing, at how Silco just walked past the ‘man’ in charge. She doesn’t level her gun at him, and those around her are grinning or smirking. What threat could one lanky miner be?

“Turn the fans back on,” Silco tells the woman.

She just snorts. “Ain’t I’s the one in charge, cutter.” She tilts her chin towards the youth pretending his voice hadn’t cracked on that previous ‘hey’. “S’him you need t’play nice with.”

“I don’t have time to barter with infants,” Silco says, as he feels the spark growing in his chest. “Turn the fucking fans back on.”

She’s not impatient, but she doesn’t like when people completely ignore the chain of command. A little rebellion is cute, but he’s pushing it. “Now, cutter.”

He holds his ground. There are people in the dark. “You want to explain to the Company why all their workers are dead? You want to take that kind of responsibility?”

The youth’s voice is closer now, right behind Silco. “It’s my mine, shit-for-brains, and I say the fans stay off.”

Silco turns, slowly, and there is no time to feel the victory in watching the youth momentarily flinch (yes, boy, these are what real scars look like, the scars of poison and near-death, not the scars you paint on when you get high for fun; this is what real danger does to the skin and the eyes). He doesn’t say anything, because how can this child own the mine? The name on the Company papers is prestigious, yes, and monied. But it’s older than Silco, so certainly older than this boy. Silco’s lip curls in disdain for the sight before him.

The tattooed teen takes offence. “You don’t think I know what you shit-shovellers have been doing? Someone needed to teach you a lesson. So here I am.” He pokes Silco in the chest, relishing in the two inches of height he has over Silco. “Da’s been sayin’ how much trouble your little ‘collective’ has been making, how much it’s costing him. Someone had to do something.”

Silco dusts off the front of his shirt, as though the mine dust were more appropriate than the touch of a shitheel with too much money. “So it’s not your mine. It’s Daddy’s mine, and you’re hoping this makes him proud of you.” He snorts his derision, though he is keenly aware of the ticking clock, of the danger that he alone can undo. He is not distracted.

The teen sneers down at Silco. “You should learn your place.”

“And where is my place, exactly?” Gas is soft, and subtle, it only takes a spark to ignite it. It only takes a spark.

“With the rest of you worthless pieces of garbage belong. Six feet un—”

Silco drives his elbow into the teen’s chest, hitting that spot in the middle of the ribs that can leave someone gasping, breathless. The teen staggers back, losing his balance. Silco follows through, stepping forward, drawing an arm back for a quick jab of a punch to the tattooed teen’s face. Silco is not strong, by comparison to the miners. He cannot swing a pick without tiring. But a single punch is no problem for a man who pushes carts all day, and this one strike seems to exert more force than the teen was expecting… or could handle.

Such a punchable face and no-one has followed through before? Hah.

There are carts on the rail. Silco works with the cart-crew. He sees to the maintenance and wellbeing of every single cart. He knows the right pressure to place to make them slow, or speed, or move along the tracks counter to gravity’s gentle incline.

So when the teenager falls back into an open cart, stunned and gaping and limbs all askew, Silco barely even has to look to know what part of the cart mechanism to kick. The gears grind with sudden alarm, and the cart seems to dart back up the hill like a startled beast. The miners who have risked sunlight and bullets to stand in the cavern entrance see the cart coming; they call for ‘gangway’ to those behind them, and everyone steps aside to let the cart whizz past, down the empty track and into the dark.

Silco turns back to face the mercenary, who is holding her gun with less certainty, her eyes wide as she looks at Silco.

“Turn the fans back on,” he says, as he shakes the pain out of his hand. The shitheel teen had a hard skull, and Silco’s knuckles feel bruised. “Unless you want to be responsible for him, as well.”

The mercenary looks at the others around her. Their master, their meal ticket, is suddenly at risk. They never thought this could happen. They never even dreamed that with all their numbers and their guns that it could ever go like this. Now they’ll be answering to a higher power, a power with more money and a lot less patience. Perhaps no patience at all, if this son has any value to the business.

They could have opened fire, but hey missed their window of opportunity. Silco’s out here in the open, but the ore miners are coming forward with pick and shovel. The numbers are shifting. There are thousands of the miners, and not even guns can change that.

“Better hurry,” Silco says, folding his arms, glaring up at the woman. “Depending on where in the gas-flooded mine that cart ends up, he could be dead in a matter of minutes. I imagine that won’t look good on your record.”

“Fuck’s seekes,” the woman hisses, staring at Silco. “What are you?”

He meets her gaze, unblinking. “I’m someone who wants the fans back on. Now.”

---

There is an illusion of sunlight here. Silco cranes his head back to look at the hazy layer of Zaun Grey, and at the way strategically-placed lights on this building send beams through it. The electricity costs must be exorbitant, but the effect from street level is that this building - with its finely-crafted architectural facade and mosaic entryway - is an oasis in the grime.

Artifice. Showmanship. The territorial display of some kind of ornamental animal. Silco is looking at the district headquarters of the Company.

Silco rolls his shoulders, then strides forward to cross the street, headed for the thick brass double-doors. There is no security outside the building to chase off riff-raff like him. The facade of the building is intimidating enough: all that light could blind and burn.

There is a small airlock, designed to keep the air outside out and the air inside in. When he steps through to the interior proper, it hurts to breathe for a moment. Fresh air, cold and crisp. Forget the lights, the cost of this building’s air processing would fund a mining operation for a year. Though, no, he cannot discount the lights; they are a soothing colour, but bright enough to illuminate everything, to let guests see just how neat and precise and clean the interior is, compared to the outside world.

There is a receptionist at a desk at the other end of the lobby. Her polite vapid expression is tight as Silco coughs in the clean air, but she is paid enough to maintain her perfect hair, perfect nails, perfect uniform, and a perfect customer-service attitude.

Silco holds her gaze as he coughs once more, steadying himself, before he strides across the open floor. There is status and wealth in this floor, and in the columns, the high ceilings, the framed oil paintings of the industry leaders and financial partners, but Silco does not look at them, leaving them merely to be noted in his periphery. He does not have time to appreciate that everything about this place is designed to make those who enter look and feel shabby and dirty and small in comparison. He doesn’t have time for that, nor does he care to. He maintains his eye contact with the receptionist, watching that professional smile become more and more rigid as he approaches her with confidence.

“I’m from the Miners’ Collective,” he says, as evenly as the too-pure air allows. “I have a meeting with the Head of the Company at twelve-twenty-five.”

The receptionist was clearly expecting ‘the Miners’ Collective’ to have brought more representatives. One is a relief, but still… this might still be one too many. She invites him to take a seat.

Silco thanks her - with matching false politeness - and says that he would prefer to stand. After all, it is twelve o’clock already. He sees no reason to sit down for twenty minutes. He will remain in the lobby of this fancy building, dirty and rough and in his shabby work clothes, and completely at ease under the gazes of the painted individuals who have never worked a day in their life. Silco takes three steps back from the desk and waits, hands lightly clasped behind his back, ignoring the plaintive attempts to get him to move out of eyeshot of anyone else who would wish to enter. Silco continues to politely decline further invitations to sit as the moments tick by, ambling back and forth in the lobby without doing anything in particular. Just being present is annoying enough.

He knows the Company means to shove him off to one side, to make him wait until it is a convenience for them to see him, despite the open candour in the invitation he received. Therefore, he will not be a convenience. He will be noted, and he will not be ignored, and he will be difficult until they accept he is here not as a slave or a pet or a beggar. He is a worker. He is here to represent the mines, and all who do the real work.

He could have - maybe should have - brought others with him. But the invitation was for him alone, identifying him by name and employee number. Neither of which the receptionist has asked for, of course, which amuses him to no end as she calls him ‘mister’ or ‘good fellow’ in an effort to get his attention. He doesn’t look up; he’s a miner, and young, and cannot afford any title, and she should have remembered to ask for his name, as part of her job and under the veil of respectability, even if she didn’t like his muddy boots or direct eye contact. Oh, which reminds him…

At the twenty minute mark, he taps the heels of his boots against the tiled floor, dislodging the mud he brought with him. It wouldn’t be good to track it into the building any further; they probably have carpets upstairs.

The Company’s intent was clearly to unsettle and unnerve him while he waited. He was prepared for that, so it did not work. And the longer he was made to wait, clearly the more mess he was going to make. At twelve-twenty-eight, the receptionist gets a buzz from a device on her desk, and with the terse, clipped remains of her professionalism she tells Silco the room number he can go to. He is offered the elevator.

Oh, but he feels like taking the stairs, doesn’t he? Maybe trudging more mud into the building? At least, until the elevator arrives with a pleasant (insistent) ding, ready and waiting for him. Very well, if this is most convenient for everyone involved? So be it.

It was so much faster than the elevator in the mines. So much smaller, too, with mirrors and brass and all so clean and well-lit. It isn’t practical at all; it’s a show piece, matching all the rest of the Company building. It is claustrophobic in here, but he is used to smaller spaces. Here, he stands on his own two feet, and is not held by the earth but instead elevated over it.

He steps out of the elevator, down a hall, to a door half-ajar for him. The mine owner - a board member of the Company - is waiting to meet him.

The man sits behind a desk, behind which his walls are lined with books and framed pictures - paintings, but also the greyscale photographs and newspaper clippings of clearly important events - as well as other signs of education and privilege. There are piles of papers on the man’s desk, so neatly-arranged, they couldn’t possibly have been what he was working on. They are there to show how heavy a work load the man has.

But Silco is not impressed. Stone and ore weighs more than paper.

The man introduces himself, but does not ask Silco’s name. He has that forced polite look of someone who intends to humour his audience, while making his own decisions afterwards regardless of what is discussed. He is asking Silco to explain himself - and the Miners’ Collective, if that is who Silco truly represents - about why they would threaten their own livelihood like this.

Silco doesn’t introduce himself, or simper or plead. He opens with dates and numbers, solid proof of the mine’s productivity increasing season by season. He ties each season to the plans of the Miners’ Collective, to the demands made for proper death and injury payouts, for safety, for alternating shifts. It is too soon in the season to definitively tell if the addition of short breaks has increased productivity as definitively, but Silco is able to mention the increased output that, if allowed to continue, could lead this to being the most productive year yet. And it is not just input and output he is able to describe, but also to the actual finances, to the decreased cost in death and injury payments which should, in theory, be an increase in profits for the mine owners, of which the Company should be well aware.

The Company Leader’s fixed and vapid look has faded. There’s something wary in the man’s eyes now. He hadn’t expected a miner to be eloquent, or capable of rational thought, let alone to have a fine grasp of business acumen.

Silco briefly outlines some of the future plans discussed by the Miners’ Collective, in the availability of equipment and tools, education for the children, and an increase in wages. Before the Company Man’s hackles can rise, protective of his money, Silco gently explains. “We want to work, all of us. This is our livelihood, and we are all proud of what we do. We are only fighting for these improvements because we know that workers who are fed, prepared, and safe produce more, and can work harder.” Words carefully-chosen to appeal to a man who has never set foot in the dark.

“And yet,” the Company man said, “You nearly killed my son.”

Silco shook his head, grim, pitying. “Your son was under the belief that the Miners’ Collective is a detriment to your business. As I have already explained, the opposite is true. It would seem your son does not know the proper way to run a business. Perhaps this experience will be the education he is sorely lacking.”

“If you think…”

“Your son,” Silco interrupts, “Brought an army of mercenaries to the mines and turned off the generator fans, intending to kill every single miner in the complex. In addition to the fact that mercenaries cost money, sir,” a terse little word, spoken as emphasis rather than respect, “Replacing an entirely workforce of men, women, and children is even costlier. Not to mention that kind of population would have to be brought over from other districts, which would be an entire new headache for you, dealing with red tape and import and relocation taxes. And then, let us not discount the fact that the mine would be full of corpses, which is in no way an easy thing to undo. The cleanup would take months, and the morale of the new workers would be far too low for productivity. Your business would suffer immensely; perhaps, even, no new workers would even be found, because of the reputation of the Company’s brutal clean-slate policy. A reputation which other Companies would use as a worst-case scenario, to motivate their own workers while demeaning you and yours even further. Perhaps you would have been brought to answer to your shareholders, or to Zaun’s ruling board, if they deemed this mismanagement egregious enough.”

He puts his hands on the Company Man’s desk and leans forward. The man is listening, his eyes on Silco’s.

“That is the scenario your son’s actions would have led to, had he been allowed to continue unchallenged. I am sure you can understand why, from one man of hard work to another, why the Miners’ Collective could not allow this to pass.”

The Company Man’s eyes narrowed. But it is from the challenge as well as from the thoughts, the weighing up of options. The consideration of numbers and facts and the threat of a darker (less profitable) future.

“You need good workers to run a business,” Silco says, quietly, evenly. “And the Miners’ Collective is made up of the best there is. The improvement of our circumstances is the best case scenario for your business. We are loyal to our work. You could give us a reason for our loyalty to increase, along with our productivity.” He straightens up, leaning away from the desk. “We would not have killed your son. But he did not know what he was doing, putting your business at risk like that.”

‘Your business’. Not ‘our lives’. Silco chooses his words carefully. He has been speaking to the miners and foremen for years, now, he knows how to craft the phrases that matter, though it does seem bitterly unpleasant to have to cheapen his life, and the lives of the miners, just to appeal to a Suit.

Silco lets the Company Man thank Silco for his time, endures the useless platitudes of ‘we’ll see what we can do’. Silco understands that he is being dismissed, that nothing will be done. Why would it? The Company has a line to draw, and this line is so often the bottom line they mean to maintain.

Silco takes the waiting elevator back into the lobby. The mud and dust he has left on the polished tiles has already been swept away. The receptionist pretends he is invisible. The airlock seals definitively behind him, as he leaves the building and goes back out into the poison air where he belongs.

But for once - for once - someone higher up the chain has listened to him. Perhaps he could be allowed to hope, cautiously.

—

Vander’s laugh filled the space, drowning out the laughter and the static-touched music coming from the jukebox on the other side of the room. The beer they were drinking was sour and lukewarm, and the air smelled of stale smoke and vomit and piss, and far too busy, but it felt like a reward after the day Silco had endured.

Most people don’t get to see the inside of a business like that. Vander hadn’t been the only one listening, with other tables either eavesdropping or leaning in to ask questions of their own. But now in describing the meeting with the Company Man, most lean back and shake their heads, either out of disbelief that a youth in canvas coveralls and patched-elbow workshirt would have been allowed it, that this must be a tall tale, while others wanted nothing to do with Companies or Suits during their time off. There weren’t many miners in this part of town, but everyone who came to this bar had a hard profession of some kind, as all work was hard in the streets of Zaun. Folk could sympathise, of course, but they were smart enough not to listen too closely, in case those in power came to call.

So it is Vander alone who listens, and grins, and laughs at Silco’s boldness. “Surprised he didn’t toss you on your arse for that. That was it? Just a ‘your time’s up, off you trot’?”

“That was it.” Silco sips the sour flat beer, and shrugs one shoulder. “I’m wondering if I should have told him about plan to ask for increased wages. It certainly feels like it shut a door.”

“Well, then it’s the Company’s job to open it again, yeah?” Vander grinned, and chuckled. “I can’t believe you went there alone.”

“It was just a,” he raises his free hand to make air quotes, “‘Friendly discussion’. So I didn’t see the need to.”

“Didn’t think a Company could be,” Vander makes matching air quotes with his own free hand, “‘Friendly’.”

Silco smirks. “Well, we’ll see.”

Vander shifts, sliding his free hand to support his chin, elbow on the table, just looking at Silco. His messy bangs half-obscure his face, tempting Silco to fix them. Silco, somehow, manages to abstain. It will make Vander pout, after all.

Vander tries not to pout. “So,” he says, “What’s next?”

Silco’s thin shoulders pitch up in a shrug. “Back to work. More meetings, though we’ll need to find another place to hold them, just in case the Company or that shitheel kid decide to stir up trouble. But just work.”

Vander’s mouth opens, then his eyes flick under his hair towards the door. His expression changes. “Oh, wow, speak of the demon himself.”

Silco snorts into his drink, choking on a brief laugh. “You’re not serious.”

“Sorry, Sil, but the shitheel’s here. You summoned him.” He smirks.

Silco glances over his shoulder. There he was, that tattooed teenage twit. “He’s brought friends,” he notes, seeing the three others following his head. The shitheel was making a direct beeline to where Silco and Vander were sitting. Someone must have run off to tattle. Someone listened, and decided to find power, hoping for a reward. It happened, from time to time, so Silco was not surprised.

“Friendly,” Vander notes, and both of them chuckle together, before they decide to finish their drinks. Vander finishes first, of course, but Silco sees no reason to rush. By the time he puts down his mug, the shitheel and his friends are all around the table, glowering down at Silco.

“Evenin’, lads,” Vander says, as Silco finishes up. “How can we help?”

“Mind your business, morshkoy-pyos,” says the one on the left.

Silco looks at the teenager. The Company Son has fresh bandages around his neck; an emergency transplant of his eso-filter, it looks like; mine gas could corrode and melt the fancier models. There’s a sallowness to the teen’s face, too, a pinch to the skin that tells of paralysed muscles similar to Silco’s own, but much much milder. Gods, it must be nice to be able to afford all kinds of medicine and surgeries, to have you back on your feet the next day after inhaling a lungful of mine air.

Silco gets to his feet, again claiming the small advantage of height he has over the tattooed teenager. Vander, too, gets up, and his advantage is greater, standing head and shoulders after all of them.

“His business is my business,” Vander says, stepping up with his teeth bared in what might be a smile, “So let’s try to be civil, tar’han.”

The teen sneers at Silco, eyes full of hate. “You,” he growls, surgery and implants doing for his voice what puberty could not, “You need to learn your place.”

“The last time you said something like that,” Silco says, quietly, “You ended up on your ass, and then six feet underground. Think your threats through, little boy.”

“I’m sixteen, you—”

“And I’m seventeen,” Silco interrupted, impatiently. “What’s your fucking point?”

“Wait.” Vander leaned in. “Hold on. Sil. You’re seventeen? No. I refuse.”

Silco looked up at Vander in amusement. “I am.”

Vander blinked, pushing his hair back out of his face. “You’re younger than me? How in the good gods damn…?”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Silco grinned, feeling the skin of his face moving, “Were you expecting me to be your sugar daddy?”

“Well, it would’a been nice, but I’m just…”

“You know I’m broke, right?”

Vander pinks up quickly. “That’s —! That’s not the—”

“Hey!” The shitheel stomped his foot. “I’m talking to you!”

Silco noticed at this point that the bar was certainly very quiet, that people were watching either to see a fight or averting their eyes so they didn’t get involved. The music had stopped. Even the shitheel and his friends seemed to realise how much of Zaun was watching them at this very moment, but there was pride at stake. Pride that had certainly not been undermined by the petulant foot-stomp.

Silco let his smile drop, a sudden and frightening return to neutrality. “Then say something worth paying attention to.”

“You need to be taught a lesson—”

“Really? Because your father seemed to think it was your education that was lacking, not mine.” He folds his arms. “You want to inherit a hole in the ground full of corpses? Or do you want to man the fuck up and learn how the world works?”

Vander snorts a laugh, a laugh that turns into a disapproving hum as the shitheel brings out a flick knife, and the others all pull weapons out of the jackets and pockets.

“No,” says the shitheel, in a voice gravelly and intentionally intimidating, “You need to learn how the world works.”

Silco smiles. “That’s a very nice knife. Isn’t it, Vander?”

“Very pretty.” Vander agrees, leaning his hand on his chair, casually shifting his weight. “Would you like it?”

“You know,” Silco says, “I think I do.”

The shitheel was getting tired of being interrupted. “You’re going to pay for—”

Silco had very sharp elbows. That could be why he was constantly patching the elbows of his shirts and jackets. The bandages around the shitheel’s throat are too easy a target. Vander hefts the chair, and then one wild haymaker. Silco goes for a wrist, an elbow, a jaw: quick aggressive jabs with unexpected force.

“Thumbs out!” Vander cheerfully reminds Silco, as they both clean up the last man standing.

“Thumbs out,” Silco shakes out his bruised knuckles, smirking. He glances over to the bartender. “Sorry, good fellow, we’ll take this outside.”

Vander grumbles something about the heavy lifting, but tosses the gagging, choking shitheel over his shoulder, then grabs two wrists and one ankle, dragging the shitheel’s three unconscious friends out behind him.

Silco bends down, and picks up the pretty knife, folds it, and puts it in his pocket. Then he follows Vander outside, whistling a work tune and slipping a coin into the jukebox as he passes.

0 notes

Text

Wangxian but make it a Disney flick for furries

Alternatively titled: I went insane for 7 hours and created these in a haze

#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#wangxian#lan wangji#wei wuxian#lan sizhui#mdzs fanart#featuring: lwj as a white tiger#wwx as a silver fox#and lsz as an arctic fox#what's the story here? idk figure it out#I used a lot of fox and the hound screenshots for reference so#em draws#also yes these ARE intended to be seasons#Summer: meeting as children#Fall: Companionship as youth#Winter: Hard times#Spring: Contentment as adults

766 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm ONLY counting the films from the Walt Disney Animation Studios line-up between 1967 (after The Jungle Book) and 1989 (before The Little Mermaid). There's some debate on what this era of Disney animation is called, so I went with both titles I tend to hear a lot. I feel like this poll requires a fairly niche audience since a lot of these are (sadly) forgotten.

#Starling polls#Disney Film Era Polls#Disney#Disney Bronze Age#The Aristocats#Robin Hood#The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh#The Rescuers#The Fox and the Hound#The Black Cauldron#The Great Mouse Detective#Oliver and Company#original post#1k+ votes#100 notes#500 notes#1k notes

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

662 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fox on the run by sweet and Scooby-doo were my greatest inspiration for such a masterpiece

Question is what are they running from ?

Is it corridor ghouls? Cthons? Or worse…fan girls

#star wars#the clone wars#clone troopers#commander fox#commander thorn#commander thire#arf trooper hound#sargeant hound#grizzer#fox on the run#scooby doo#the corrie guard#coruscant guard#the corries

821 notes

·

View notes