#hydrogen atoms

Text

SPACEMAS DAY 19 ✨🪐🌎☄️☀️🌕

By some weird chance, the outline of this molecular space cloud resembles the outline of the state of California, USA. Our Sun has its home within the Orion Arm of the Milky Way, only about 1,000 light-years from the California Nebula. Also known as NGC 1499, the classic emission nebula is around 100 light-years long. On the featured image, the most prominent glow of the California Nebula is the red light characteristic of hydrogen atoms recombining with long lost electrons that were stripped away (ionized) by starlight. The star most likely providing the starlight is the bright, hot, bluish Xi Persei just to the right of the nebula. A regular target for astrophotographers, the California Nebula can be spotted with a wide-field telescope under a dark sky toward the constellation of Perseus, not far from the Pleiades.

Image Credit & Copyright: Steven Powell

#astronomy#space#science#universe#spacemas#day 19#nebula#California#California nebula#light year#red#hydrogen atoms#hydrogen#starlight#electrons#follow#like#reblog#the first star#the first starr#thefirststar#thefirststarr#nasa#apod#tumblr#blog#space blog#space tumblr#gas cloud#Orion arm

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Water

There are more hydrogen atoms in a single molecule of water than there are stars in the entire solar system.

1 note

·

View note

Text

There are more Hydrogen atoms in a single molecule of water than there are stars in the entire Solar System.

Wadsworth_McStumpy,Vlad Chețan

0 notes

Note

How do you build a atomic bomb?

Easily!

All you need are a few household items, a little bit of patience, and a Class 1 Top Security clearance for the manufacture of biological, chemical or nuclear weapons under the Fermi laws of 1954 contingent to permission from the United Nations Security Council.

You're gonna need-

A box of matches

A blender

Tape

Some wire mesh (Like a window screen, for sifting)

Cake mix (Yellow sponge cake works best)

Ziplock bags

String

Ice cubes (The cold kind, not the rapper/actor)

A toilet paper tube

A Catholic Missal

An empty kitty litter bucket

First, you're gonna need two rare substances- Weapons grade uranium and "heavy" water. For the uranium, just take your yellow cake mix and sift it with the wire mesh. Whatever stays on top of the mesh- That's weapons grade. For the heavy water, take some ice cubes, which are heavier than water but still made of water, and put them in the blender. By breaking up the ice cubes and releasing the water, you keep the weight but make it a fluid. This is a process that scientists call "Putrefaction".

To build the weapon, pack some uranium into one end of the toilet paper tube and then cover that end with the Catholic Missal. This guarantees what we call a "Critical Mass" of uranium. Then take a smaller wad of uranium and pack it into the other end of the tube, leaving plenty of space between the two.

Tape the box of matches to that end of the tube. It will act as an explosive device to send the "bullet" of uranium into the critical mass, thus resulting in a nuclear fission explosion.

You now have a nuclear fission device! This device has a yield equal to about 10 thousand tons of T.N.T. But fission is for wimps, right? So let's turn that fission bomb, into a fusion bomb!

Tape your string to the matches to act as a fuse, and then put the nuclear warhead in a ziplock bag. Be sure to seal it tight! Now place that assembly into the kitty litter bucket. Make sure it's empty of kitty litter before the next step.

Fill the rest of the bucket with the heavy water you made in step one, and seal the top of the kitty litter bucket with the string still poking out. Once the fuse is lit, it will light the matches and detonate the nuclear fission bomb. This acts as a heat source to boil the heavy water, and when heavy water boils- Nuclear Fusion!

Congratulations, your bomb is now complete. Remember that it's illegal to carry or detonate a nuclear fusion warhead in public (except in Texas), and bear in mind this will be quite a bit stronger than your usual firecrackers. We recommend only setting off your nuclear device on official U.S. testing grounds, such as the desserts of New Mexico or islands in the Pacific only populated by tribes under no country's protection, because that's seriously what the U.S. did.

So play safe and have a good time,

-facts-i-just-made-up.tumblr.com

#nuclear weapons#atomic bomb#hydrogen bomb#global thermonuclear war#would you like to play a game#unreality

533 notes

·

View notes

Text

FUN FACT!

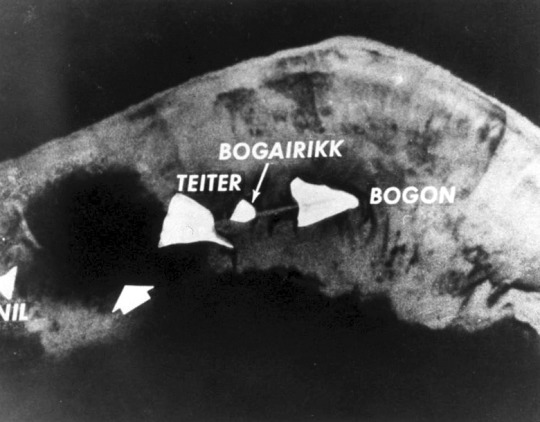

the first ever hydrogen bomb detonated (Operation Ivy: Shot Mike) completely vaporized the island it was detonated on, leaving a giant undersea crater in its place. there was an island there, and now it's just fucking gone.

The island was Elugelab in the Enewetak Atoll

Before the Ivy Mike test:

After the Ivy Mike test:

the thing about the Ivy Mike test, though, is that the bomb was too big, impractical, and heavy to carry in an airplane, afix to a rocket, or fire from a canon. still, the blast had a yield of 10.4 megatons, rivaled only by the infamous Castle Bravo test (US 15 megatons), the B-41/ Mk-41 Bomb ( US 25 megatons), and the Tsar Bomba test (USSR 50 megatons).

The rest of these bombs can be dropped from airplanes. The Tsar Bomba design was, however, never put into production as a practical weapon and was simply intended to be a one-off exercise with the goal of creating the largest yeild atomic weapon in history. (it succeeded)

#world history#us history#atomic testing#hydrogen bomb#castle bravo#ivy mike#tsar bomba#infodump#spin#special interest

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was playing basketball with Samus Aran and at the end she turned into a hydrogen atom.

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

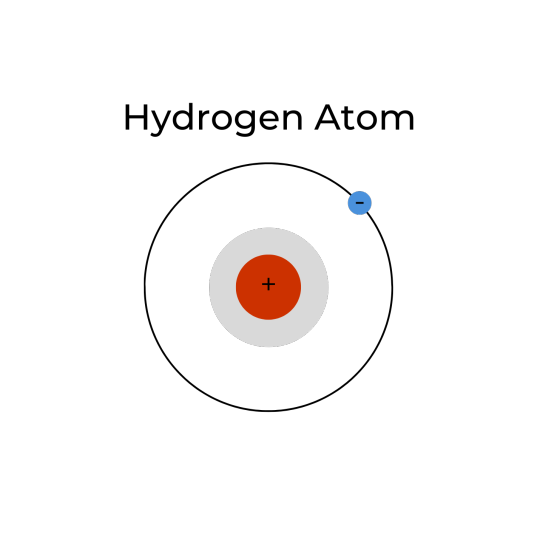

the first Element

H

Lightest & most abundant element in the universe, powering the stars & making up a crucial component of water! 💦☀️

Hydrogen-1 is the only known element with no neutron in its nucleus!

Have you heard of hypothetical Hydrogen-0, with no protons or neutrons?

#hydrogen#element#atom#classic#science#core#proton#H#loop#seamless#visuals#orbit#gif art#blue#chemistry

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Periodic table day!

#ATOMS#H#hydrogen#O#oxygen#periodic table#elements#chemistry#science#periodic table day#character#oc#illustration#digital painting#procreate#web comics#comic#webcomic#webtoon

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmmm….

….

Yes I know the recent video already alluded to this.

Even if it first appeared in the Nixonverse.

I made a post about that too.

Still.

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#gifs#hydrogen atom#hydrogen#atom#atoms#my poor attempt at a joke#what#no context#mister manticore#monument mythos#mirrors lie twice#this sounded funnier in my head#shitpost#analog horror#the nixonverse#tangentially

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

74-24-2 is recommended for a beginner's universe, but the first rule of creation is to have fun!

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

google and my chemistry teacher are conflicting rn

im confused about the argon d orbital now ToT

NOW IM QUESTIONING LITERALLY EVERYTHING I KNOW ABOUT THE ELEMENTS @allhailhelium send help

anyways, take some more atom doodles

#helium feels very strongly about abstinence#(aromantics :>)#I only have the elements designed up to arsenic so thats why Argon's getting targeted#lithium lost his 'hair' because traumatic backstory involving water#scary right#even the atoms aren't safe from whump#chemistry#helium#argon#magnesium#chlorine#fluorine#hydrogen#lithium

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

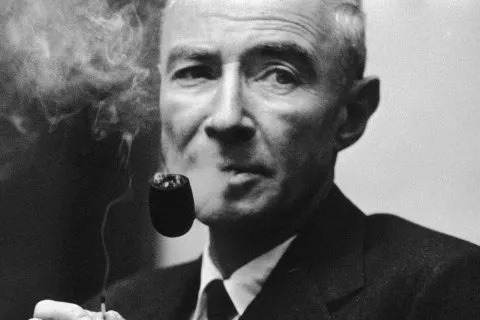

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

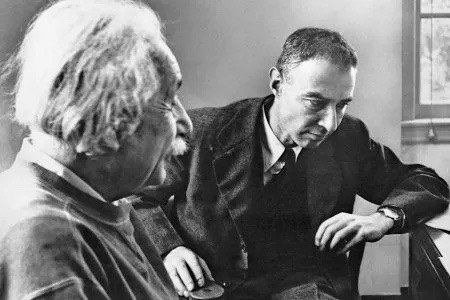

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Chemtry time?

Quick what is water

(you got this! :D)

water is wet

#[gets shot]#WATER IS A POLAR MOLECULE BETWEEN ONE OXYGEN ATOM AND TWO HYDROGEN ATOMS WITH A PH LEVEL OF 7 AND ACTS AS BOTH ACID/ BASE FOR ANY REACTION#do I win

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

“All distances in time and space are shrinking. Man now reaches overnight, by plane, places which formerly took weeks and months of travel. He now receives instant information, by radio, of events which he formerly learned about only years later, if at all. The germination and growth of plants, which remained hidden throughout the seasons, is now exhibited publicly in a minute, on film. Distant sites of the most ancient cultures are shown on film as if they stood this very moment amidst today's street traffic. Moreover, the film attests to what it shows by presenting also the camera and its operators at work. The peak of this abolition of every possibility of remoteness is reached by television, which will soon pervade and dominate the whole machinery of communication.

Man puts the longest distances behind him in the shortest time. He puts the greatest distances behind himself and thus puts everything before himself at the shortest range.

Yet the frantic abolition of all distances brings no nearness; for nearness does not consist in shortness of distance. What is least remote from us in point of distance, by virtue of its picture on film or its sound on the radio, can remain far from us. What is incalculably far from us in point of distance can be near to us. Short distance is not in itself nearness. Nor is great distance remoteness.

What is nearness if it fails to come about despite the reduction of the longest distances to the shortest intervals? What is nearness if it is even repelled by the restless abolition of distances? What is nearness if, along with its failure to appear, remoteness also remains absent?

What is happening here when, as a result of the abolition of great distances, everything is equally far and equally near? What is this uniformity in which everything is neither far nor near - is, as it were, without distance?

Everything gets lumped together into uniform distancelessness. How? Is not this merging of everything into the distanceless more unearthly than everything bursting apart?

Man stares at what the explosion of the atom bomb could bring with it. He does not see that the atom bomb and its explosion are the mere final emission of what has long since taken place, has already happened. Not to mention the single hydrogen bomb, whose triggering, thought through to its utmost potential, might be enough to snuff out all life on earth. What is this helpless anxiety still waiting for, if the terrible has already happened?

The terrifying is unsettling; it places everything outside its own nature. What is it that unsettles and thus terrifies? It shows itself and hides itself in the way in which everything presences, namely, in the fact that despite all conquest of distances the nearness of things remains absent.” (p. 165, 166)

13 notes

·

View notes