#inspired by Hungarian folk clothing

Text

Countess Orlok and her guards

#oc art#original character#character design#wip#vampire#nosferatu#folklore#yes I'm drawing this with symmetry guide on#because i'm lazy#countess is bit funky looking because I just wanted to sketch her dress at first#inspired by Hungarian folk clothing#digital art#i have no idea what im doing#bald lady#hehe#undead guys

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

what sort of time period and region is your comic set in? dantes outfits are cool and I’m wondering if they’re inspired by real life cultures

Howdy! Thanks for asking!

So it’s a big ole smorgasbord

Time period is medieval. Closer to the 10th-11th century, but I’m going to be fucking around in this. For instance, in the story Christianity is just now getting introduced to Northern Europe when in reality it happened closer to the 7th century. But in the story, ppl are still following a pagan religion (which is inspired by the Celt’s deities but set up closer to a Roman pantheon) and the antagonist is backed by the Roman Catholic Church because I want there to be religious tensions as big motivators for all the major background players

But then culturally, I’ve been looking at the Celts specifically with a little bit of research into Slavic history and folklore. I’ve also been doing research on the culture in the Alps because I want the kingdom set in the topography of the Switzerland. So these are the big three cultural influences

For their clothing I think you can see my biggest influence is Slavic folk costume. I’ve been looking the most at Ukrainian and Russian clothing but I also adore Hungarian clothing and embroidery. I do plan to try and keep some Swiss and Celtic influences, but the Slavs really fucking nailed it in terms of clothing that make me want to swoon. Although I plan to make my own embroidery meanings. I’ve been researching what plants are native to the alps, and then figuring out their meanings, and then I plan to associate each character with a plant I think represents them best and make an embroidery pattern based on that for said character.

Right now though with my art I’m fucking around, so the embroidery you see doesn’t mean anything at all. But in the actual comic it’ll be more legit

Biggest piece to note though is that I do call this a fantasy story, not a historical one. These are all my influences, but my main goal is to get it to read a bit more like a fairy tale. Also I don’t want to deal with the feudal system, so I’m just not tbh

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I happened to see your OC and was intrigued by the name, as it sounds as if it is of Romanian origin. After having a better look at the clothes, they vaguely remind me of traditional clothing from Romania, too. ^^ So I was wondering how you came to pick it, if anything? Name-picking for characters is always an interesting process, so consider me a curious native!

native???

Buna!

I'm Romanian, so, yeah.

Old folklore stories. Hungarian folk tales too (the cartoon), this one old book called "Calutul Fermecat" from what I remember.

Since he's basically inspired by the balaur and zmeu (with slight hero inspiration). I took a lot from those childhood stories, well what I remember from them.

The clothes are that way because I love the aesthetic of those big silk-like "vampire/pirate" shirts, the pants felt like they fit and I didn't want to give him dress shoes so I went with boots. The flowers were added later because I thought they would fit nicely, and they along with the clothes are inspired by folk clothes.

Considering his minor nobility status, he's basically a boier.

The name was on the spot, because I'm not that good with them.

Basically the feminine name Laura, but made for guys hence Laur (I think there might actually be guys with that name around)

It also makes a nice connection with laurels and Dafin as bay.

Those are considered to have magical properties with regards to money and since he is what he is, Laur is good with riches. Adding the rooster from "Punguta cu doi bani" as his treasurer also helps in that regard.

The magical horse he has is generally the companion of the stories hero, but Laur is inspired by the villains, though he is a pretty chill guy.

His UM is inspired by what usually happens in folk tales, think "Fata babei si fata mosului"

It's all an amalgamation of what I remember and my imagination put into the context of TWST.

Also... the Iron Gates?👀 sounds familiar doesn't it?

If you want we can talk more about it.

Feel free to ask about my boy anytime!

#twst oc#twisted wonderland oc#twst original character#unripe tomato#Laur Dafin#twst#twst wonderland#twisted oc

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

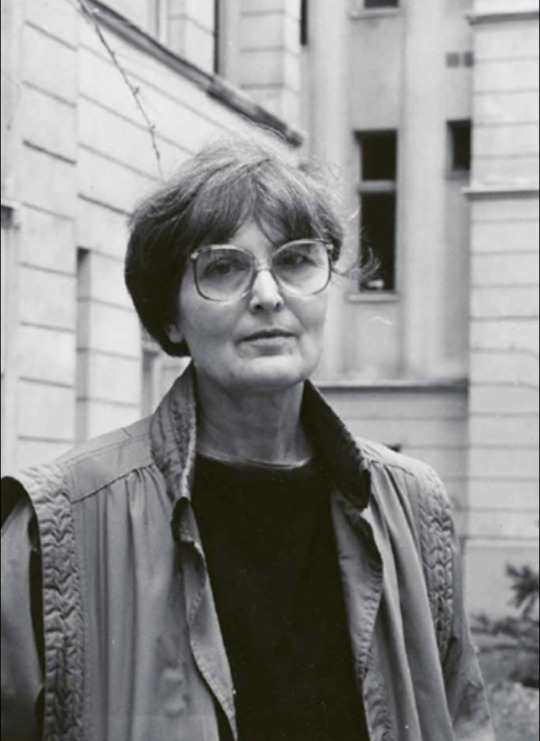

Margit Szilvitzky

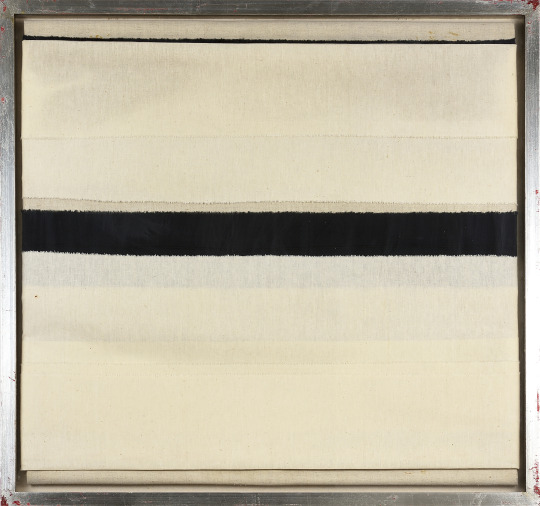

Margit Szilvitzky (1931 – 2018) graduated from the textile and fashion design department of the University of Applied Arts Budapest in 1954. She worked as a fashion designer before beginning to experiment with fabric.

Following her early artistic period, inspired by the history of clothing, folk art and the neo-secessionist style, Szilvitzky turned to white canvases in the second half of the seventies. It was also during this time that her attention was shifted to the square, and to a methodology of folding that reflects the influence of Josef Albers’s paper studies.

Spanning five decades, her artistic approach articulated in various media such as drawing, painting and art books as well. Szilvitzky’s serial works and process art pieces, which represented a shift toward minimal and conceptual art, drew her system-seeking attention not only to the examination of the sculptural potential of textiles, but also to the exploration of interrelation of light and shadow. She was a regular participant in international exhibitions of Hungarian fibre art (Aalborg, Helsinki, etc.), and she also took part in several graphic and artists’ book shows.

Image 1: Margit Szilvitzky, Floor Object 1, 1977

Image 2: Margit Szilvitzky, Evidence No. 2, 1976

Image 3: Artist Margit Szilvitzky. Photo by Miklós Sulyok

#margitszilvitzky#Frieze#FriezeLondon#FriezeWeek#FriezeSpotlight#femaleartists#handmade#beautiful#textile#art

0 notes

Note

Hello There fellow Hungarian from Poland!

Do you have aby headcanons about Poland or Polish and Hungarian Relations?

Yay, another Pole! :D Much, much love from Hungary to you guys! ❤️❤️❤️ I tried to summarize my thoughts in short sentences but….eh… sorry for the length of this, but there is like, a ton of history to work with, and one idea popped up after another and then I just got lost typing this. I might as well write a whole book about it. XD

These are listed in more or less historical order. Am I doing this right? I’m bad at making headcanons! Also my interpretation of Poland is very different from his Hetalia presentation and my notes are based heavily on how Poland and Polish people are perceived in Hungary. Sorry if that bothers anyone, but I like to stay accurate to History.

Anyway, I hope this list satisfies!

Poland:

-Used to be really childish and carefree but after the partitions he matured rather quickly

-He is quite the attention-seeker, very social and has many friends but only a few real ones and he has trust issues and fear of abandonment - that’s why he can get very clingy

-Has pride like the size of the moon

-Communicates his emotions poorly - which results in him sometimes mistreating people he likes (Lithuania and Ukraine for example) - he is getting better at reading people though

-He is a “lets get shit done” type of person - you give him a job and he will do it impeccably and in time

-He appears like this happy-go-lucky guy, but it’s actually a coping mechanism

-When he feels down, he becomes emotional - and drinks a lot - he is an emotional drunk

-Had a big fat crush on Ukraine (he even has a folk song dedicated to her, Hej Sokoły!)

-Complains a lot - like a really lot

-Poland keeps old gifts he received from his great kings and queens in a safe (nobody knows about it though)

-The partitions caused him to lose consciousness for weeks. It was the shock of losing his identity as a ‘state’. All countries involved believed that he would die.

-Poland lived with Russia between 1795-1918 due to Russia possessing most of his territory. But he often made official visits to Austria and Prussia to negotiate the treatment of his people with them. He also got away on his own a few times (to help out Hungary in 1848-49 for example).

-Poland accompanied Tadeusz Kościuszko to America, but couldn’t stay for long. Youthful America’s enthusiasm inspired him a lot.

-He is a very bad driver, and had so many accidents he doesn’t keep count, but he is a skilled pilot so he often complains about not being allowed to fly around instead of driving around.

Poland and Hungary:

-Poland was also victim of Hungarian tribal attacks before the 10th century so his boss decided to befriend the new southern neighbour in hopes of making an ally. At first Hungary thought Poland was a girl while he thought she was a boy.

-Hungary first met a Polish tribe called “Lendzianie” and so she named his people “lengyel”. Poland never corrected her though.

-They paid visits to each other often during the early decades of the 10th century and played a lot. Once they jumped in a lake for fun’s sake, without clothes, and Poland quickly realized that Hungary is in fact a girl but he hadn’t got the heart to break the news to her because she was so confident in being a boy.

-They got distanced whenever internal crisises rose in their countries. Even up to this day, if one of them has an internal struggle, the other doesn’t pry and keeps a respectful distance. They respect each others boundaries in every way.

-Poland and Hungary were married twice, but all they ever did was giggle about it like the young teens they were and caused a lot of trouble for their kings with their pranks and mischiefs.

-Poland never understood why Hungary’s attention turned towards Austria in the 1400s though. Hungary also never understood why his attention turned towards Lithuania either.

-Poland and Hungary have a very similar residing scar running in three directions across their bodies which are testimony to them being thorn in three. Poland during the partitions and Hungary during the Ottoman-Habsburg invasions when she was also basically three entities in one.

-Poland fought with Hungary against Austria in 1848-49 but was dragged back by Russia when Hungary lost. He learned of her marriage to Austria through a newspaper much later and was severely disappointed in her.

-Poland tried to negotiate with the Allies in order to save Hungary from being chopped up and lose their shared border, but France faced him with a decision: either shut up and get a place on the map or refuse the treaty and have less territory. Poland never ratified the treaty but he still resents not fighting it more.

-Hungary tried to help Poland during his war with the soviets in 1920-22 but because Czechoslovakia refused to grant access to him out of spite, she turned to Romania of all people, pleading him to help. Romania actually helped.

-Hungary was pretty shaken and isolated from everyone after WW1. Only Poland and North Italy reached out to her, searching ways to keep in contact.

-Hungary resents joining the wrong side in WW2, which made her and Poland enemies. She tried to make the best of the situation and help Poland when her troops were stationed on his territory. They met accidentally in a forest while Poland was marching with partisans towards Warsaw in 1944. She helped him out but Prussia found them and Hungary pretended to take Poland hostage in order to release him later during the night. Her men were killed for fraternizing with the enemy.

-During the German occupation in Poland it was forbidden to listen to Polish nationalist songs and so Hungary and her men played “God save Poland” on repeat just because they could and Poland and his people were very thankful for it.

-When the Iron Curtain was drawn, Hungary hid away in her land, depressed, but Poland kept fighting the new rule until the Poznan protests inspired the uprising in Budapest in 1956. Originally Hungary organized a solidarity march for him but it turned into a freedom fight. She was struck down by Russia though, leaving her bleeding out on her streets with a hole in her chest. Poland flew to Budapest and offered his own blood to save her. Hungary remained unconsious for a week until she woke up. He was at her bedside the whole time.

-Poland often jokes about Hungary probably inheriting his “immortality” because of the blood transfusion.

-Hungary hid away again after 56. He tried to help Hungary get over her trauma by visiting her often during the rest of their years in the Soviet Union, but something broke in her and he didn’t really know what to do.

-This put a certain distance between them.

-After the USSR fell, Poland was quick to make new friends and make up with his neighbours but Hungary came out of her shell much slower. She did admire him for his strength to move on. He also encouraged her a lot to get up and improve her country.

-Hungary considers him her only real friend. She doesn’t trust anybody else with her life anymore. Out of gratitude, she decided to declare a special day for Poland (March 23) and when he heard of it, he actually teared up.

-Nowadays they visit each other on their Independence Days and celebrate together. They also go and cheer for each other’s football teams with hundreds of Poles chanting “Ria, ria, Hungaria!” and hundreds of Hungarians chanting “Polska! Polska!” on the streets.

-After hearing the song “Varsó hiába várod” from the band Republic, Poland thought Warsaw is indeed too far from Budapest so he made a plan to build a railroad so they can come and go between each other’s capitals in five hours. The idea is under construction at the moment.

-Poland and Hungary like to think that they are the heart of V4.

-Hungary goes along with whatever mischief or prank Poland makes up. And vica versa.

-They also promote their friendship with so much enthusiasm that Romania often calls them out for being too mushy.

.

Uh, thanks for reading through this! I know this is a lots of text, I get carried away when making up ideas. I’m unable to summarize my thoughts in short sentences. I don’t have the ability.

Also 50% of this is not even headcanon, some of these really happened or are happening.

Anyway, I hope I answered your question! :’)

#hetalia#hws#aph#hetalia hungary#hetalia poland#hws hungary#hws poland#polish-hungarian friendship#polish-hungarian relations#this history is rich#i love them so much#and I love Poles so much#headcanons but not really#q&a#zsocca#zsocca55#polhun

137 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I’m a begginer artist and I love your art (I especially enjoy the cats and the clothes you paint). I wanted to know where do you look for references on clothes, since i really enjoy the style and I want to practice more. Thak you!

Hi! Thank you for liking my art! <3

The style I’m inspired by is called “mori kei” , it’s a Japanese alternative fashion, the name means “forest” ( mori) kei ( not exactly sure what it means, but it’s put after fashion style names such as “visual kei” or “fairy kei”), it’s supposed to emulate the style of someone living in the forest, hand making all their clothes.

search the tags “mori kei”, “mori girl”, “mori boy”, “dark mori” , “natural kei”( a more colorful version of the fashion) “mori kei fashion” etc on tumblr, insta and pinterest (a lot of times the pinterest ones are reposts from insta or tumblr so be sure to follow them through to their sources, let’s give them people love for their outfits <3)

check out @kesstiel ‘s or @mai-magi ‘s mori kei or dark mori tags, they also have insta accounts with the same handle, but mai-magi doesn’t really dresses in the mori style anymore.

also check out @catinawitchhat also on insta with the same handle, she seems to be inactive on tumblr but is very active in instagram, I love love love her style!! big inspo for me, not just for moriesque outfits!

My other biggest inspiration, and I think some of mori kei is inspired by that as well is folk wear!! Especially Hungarian and eastern europian folk dress, but also anything with the same “vibe” like northern europian and midlle eastern , or mongolian or manjurian traditional dress are also sources of inspiritaion. uhh maybe check out my pinterest board “folk stuff”? If you look at my blog on desktop there’s a “menu” bar at the top , I have my pinterest link there 👍😶

So yeah! These are the keywords you can use and places you can look, hope it helps!

#ask#answer#anon#not art#sorry it's so long#I have to say exactly what I mean and all the things I thought of or I'll die#mori kei used to be pretty popular in the 2010's#pretty active community and I followed some good content creators#people with coll outfits#but I moved blogs since so and they fallen out of the fashion so I lost a lot of them to the endless stream of tumblr#all the kids are now into this cottagecore thing#which is intersects with mori kei I think nut also I don't really get it lol#how is the strawberry dress cottagecore? it is opposite of mori sensibilities#so you see they're very different aesthetics#but the youngsters are also tagging my mori kei posts with cottage core#interesting#also!! I'm not fixing the typos in my tag novel sorry#also sorry all the people I recommended to look at for style are white#mori kei obviusly can be worn by anyone and is of Japanese origin#when I draw mori style drawings with people I try to keep in mind to diversify them#I'll need to keep in mind to diversify my sources as well!#I am very tired#how are you?

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hetalia Headcanons based on life in an other Counrty - PART 3

As already said in PART 1 and PART 2, I am working in Germany for one year (only 5 months left ;n;). I've met a lot of people from lots of different countries, and I decided to make Headcanons based on them.

Let's get into it!

× Netherlands has such an original taste in clothing that he often doesn't find what he is looking for. That is why he began knitting his own cardigans and pullovers.

× Denmark has a collection of socks of different designs. The Nordics like to bet which socks he is going to put today: "I bet it's gonna be the pineapple ones." "No it's gonna be the dinosaur ones!" "Idiots, he's gonna put the Christmas ones." "...gonn' be the donnuts."

× Netherlands is extremely paranoid with the internet, if he ABSOLUTELY HAS to use a social media, he will create one with a fake name and with no pictures. He tries to protect any information on him from being published on the internet.

× France is always scared to be hated, so he always thinks that everyone is watching him to judge him. He too, is paranoid in an other way.

× America once fell in love with German Lady that lived in New York, they met at a disco and it was love at first sight. It was just like in the movies. He even built her a house at the top of a hill to which there was a church just at the bottom of it.

× Canada once fell in love with a Lady that lived in New York as well, and just like his brother it was so romantic. He later found out that she was born in Germany but lived her whole life in America.

× Netherland likes to go Urbex in abandoned places. He always says "No risk, no fun!". He likes to jump into shortcuts from a roof to a balcony or even from a window to a tree. Basically he does parkour in deserted places which can be dangerous but that's how he likes to play.

× Germany think it's cool to know how to say "you're welcome" in absolutely every languages, so when he learned it in Norwegian, he began to scream at the top of his lungs "Værsågod" at absolutely everyone passing by.

× Denmark and Finland absolutely utterly love Christmas songs to the point that the other Nordics had to put a rules that they weren't allowed to listen to Christmas songs at least before November 15.

× When decorating the Nordics house for Christmas, Norway likes to have everything organized and he charges everyone tasks that they have to do.

× Poland likes listening to Rap songs in absolutely every languages even tho he doesn't understand them. He likes it so much that he has to share it with everyone and play it on a portable boombox instead of putting earphones.

× Canada made everyone believe that he had a rule at his house where he wasn't allowed to consume milk after 9pm, so no hot chocolate, cake, pancakes... It was a funny joke.

× Denmark can't sing because when he does it's awfully off-key, and he is aware of it so he likes to make fun of it by singing even more purposely off-key.

× Because of Netherlands having stroked his voice for ever, he is never gonna be able to sing in-key forever. So people make fun of him singing off-key even tho most of the time he does that on purpose.

× America has an obsession with cows, when he sees one he has to go and pet it. They are his favorite animals and he even has a pyjama suit cow, and got for Christmas an inflatable cow costume.

× One time Canada said that he didn't like cheese while sitting in the middle of France and Netherlands which the two of them turned their heads toward him with an expression of shock and horror.

× Poland fell in love with a Norwegian girl but because she knew his real age, she said he was too old for her and he respected that but still got sad that their friendship is now broken.

× Turkey sings when he is working, and even if he doesn't have a beautiful singing voice, it's very calming to hear him sing.

× The Italy Brothers are extremely proud of their products, so each time they talk about something that is originated from Italy (for example Pizza, Gelato, Ferrari...), they feel obliged to precize that it comes from their place and from which region it came from.

× France is a very good liar and can be extremely sneaky. If you play Among Us or a Mafia irl with him, be careful with him. He is very dangerous~

× America sometimes like to build things with old abandonned stuff that he finds in his house, recently he built a boat with wooden planks and plastic boxes with the help of Norway and France. It floated and it was fun to see them fall into the freezing water (6°c/42,8°F).

× Canada is obsessed with Matcha. He puts it absolutely everywhere. He probably likes it even more than Japan.

× France, Canada, Norway, Bulgaria and the Netherlands meets up every Friday to watch the Netflix show Formula 1 and they bring huge amount of snacks each time.

× Poland fell in love with an Hungarian girl (after the Norwegian girl bad experience), but he decided to keep it secret to not ruin anything, until Hungary herself told the Hungarian girl about it. Poor Poland...

It will probably be the last time I make Headcanons as I don't go much on Tumblr these days, but we never know!

As these Headcanons are inspire by real people in real life, some ideas may contradict with others and of course it doesn't apply to everyone from these countries!

Don't hesitate to ask me questions about them and have a good day folk! ^v^

#hetalia#aph headcanons#aph france#hws france#aph norway#hws norway#aph canada#hws canada#aph netherlands#hws netherlands#aph america#hws america#aph poland#hws poland#aph denmark#hws denmark#aph bulgaria#hws bulgaria#aph germany#hws germany#aph finland#hws finland#aph nordics#hws nordics#aph turkey#hws turkey#aph romano#hws romano#aph italy#hws italy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite as 100 years of Greek fashion (part 1)

Before writing this long essay post, I just wanted to give props and citations of information to both @alatismeni-theitsa and @greek-mythologies for introducing me a lot of things about Greek arts, culture, and its past history over several months now; and that this idea was also partly inspired from the common idea of modern Hellenic Polytheists as well: that “the gods are often enormously powerful beings who don’t have definitive physical bodies, and they often manifest/appear to whomsoever they wish and in any form that they wish to.” To me, since both Aphrodite and Ares have always been appeared as local Mediterranean Greeks in modern-day clothing fashion, here are some photos of what the couple themselves would wear/ dress like for over past 100 years ago.

1910s:

During this time and era, Western European fashion from the Edwardian era haven't reached to most of the Greek population, yet; and only to be worn by the royal aristocratic class and the affluent wealthy class. It was much more transition period due to the effects of Second Industrial Revolution, to be exact. Villagers who lived in both rural and developing areas back then often wore the traditional clothing (paradosiaki foresia), consisted of a simpler attire: shirt, skirt, apron, and handkerchief for women. (Even though this is not really a case for all the affluent wealthy class, as sometimes they wore traditional fashion or a fusion mix between both modern and traditional, in some occasions.) Aphrodite, in this case here, as the goddess of sex, love and beauty, wore “the traditional folk kaprasia bridal dress” from the island of Cyprus as usual, with the traditional ornate golden jewelry that Greek Cypriot families often passed down from generations to generations.

Historically, this is also the time when all countries in the Balkan region (Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia) forming allies together in order to help smaller European territories to gain independence from the ever slowly-dying Ottoman Empire; but later turn hostile towards to each other due to the partitioning of their conquests. The political Greek royal family and the Greek Prime Minister also began to ripping the Greek society apart; as Konstantinos I was married to Kaiser Wilheim II’s sister while the Greek government Eleftherios Venizelos was allied with the Allied Powers, British Empire, and France. This period of time, also marked “one of the largest chain of tragedies and sadnesses within the modern Greek history”; as the famous Greek genocides were being committed in the Anatolia region of Turkey, on the basis of their religion and ethnicity. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand of Austro-Hungarian Empire, and other problem factors that related to “Socio-Darwinism” and “colonialism” across Africa and Asia, World War I begins and Greece declares war on the Central Powers in 1914, ending three years of neutrality by entering World War I alongside Britain, France, Russia, and Italy.

1920s:

During this time and era, Europe just formed a fragile peace treaty together and WW1 had made a fundamental and irreversible effect on society, culture, and fashion; where women’s fashion were all often associated with the ideas of “letting loose”, “breaking free” and “rebel against” the physical and social constraints of the previous century. Letting go away from the extravagant and restrictive styles of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and towards a more simple, more casual chic, and looser clothing which revealed more of the flowing silhouette, the arms and the legs. This idea might have originally started in Paris and popularized by Gabrielle Chanel, paralleling with the idea of “women’s participation on the war, have the right to vote and entering the workforce to win her own liberty” -which later spread to many parts of urban cities across the Americas and Western Europe. Despite this, since Greece has always been much more socially-culturally modest and much more conservative than other Northern European countries during this time: it is either that Greek women embraced these new long flowy dresses where their skin was less revealed, or that women still embraced the dresses from the past Victorian-Edwardian eras. (But I personally think that Aphrodite herself would passionately embraced these new minimalist flapper-like looks, to be honest.)

Aphrodite’s dress and hairstyle in here was inspired from Princess Aspasia Manos of Denmark and Greece, and Queen Victoria Eugénie of Battenberg and Spain; since during this time, high end fashion trends were now become much more cheaper and affordable to people who coming from the middle working classes. The jewelry that she wore around her neck were the strands of pearls - one of the common characteristic that was popularized by Gabrielle Chanel during that time and had always been considered as “the sacred stone of love” to the goddess herself back in the ancient times- and a necklace of red coral beads. Her once ancient golden jewelry is now remodeled and incorporated with new gemstones, which was a kind of common case during that time, too. Her husband, the god Ares here wore the usual local traditional fustanella from the region of Thessaloniki-Macedonia that you guys had saw in my previous drawings. The architectural background was based on one of the oldest and the most beautiful neighborhoods in modern city of Athens, Plaka and several other neoclassical architectural pieces around the city’s center.

#aphrodite#ares and aphrodite#ares#mars and venus#mars#venus#modern day greek mythology#100 years of fashion#100 years of beauty#greek history#paradosiaki foresia#my art#kaprasian bridal dress#100 years of Greek fashion#1910s fashion#1920s fashion

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Women Who Sing for Sklep” nominated for a World Fantasy Award: read free here.

A hugely unexpected honor: “The Women Who Sing for Sklep,” a story original to Thin Places and beloved to my heart, is a finalist for a World Fantasy Award. “Sklep” is my playful troubling of Wicker Man-style folk horror, inspired by the folk music gathering project of the composer Béla Bartók and the ambivalent fascination with the “primitive” that fueled early-twentieth-century anthropology more broadly. Also, Slavic mermaids. In light of the story’s nomination, I’ve decided to make it available -- free online for the first time -- to read here. Hope you enjoy!

--

The Women Who Sing for Sklep

The composer stopped when he came to the hillside overlooking the village of Sklep. He asked his assistant to photograph the squat little houses of wattle-and-daub, sipped from his canteen, and looked upon the landscape with approval.

He rode into the village posting to his horse’s trot, stiff in the saddle after many hours of riding. His assistant was fortunate; his assistant got to walk. His assistant’s name was Triglav, after the old Slavic god, which the composer appreciated.

Sklep had no Sunday market, so the main road into town was empty, besides a woman who sold goat’s milk in glass bottles on one side of the road. The composer did not ask her where to find the town magistrate. He already knew. The house at the end of the road was taller and narrower than any of its neighbors. Already he had seen a dozen villages arranged just the same way.

In front of the tall, narrow house, the composer dismounted, put his horse’s reins in Triglav’s hands, then walked to the door and knocked. The horse nibbled hopefully at the dust in front of the house. Triglav arranged and rearranged their luggage. The composer waited, his arms crossed like two intersecting bars in front of his ribcage.

Inside the tall and narrow house, the town magistrate served coffee from an Arabic carafe. The composer’s eyebrows lifted at this display of worldliness. They were on the Hungarian plain. Last year the composer had lived with a tribe who spoke their own language and played instruments made from freshly sanded pine.

“I want to study the music of your people,” the composer said to the magistrate. “I want to live beside you and understand what inspires you.”

The magistrate did not say why, not aloud, but his brow furrowed deeply.

“Go see Magdalena,” he said.

“Magdalena,” repeated the composer.

“Come to the Cemuk festival tomorrow. I will introduce you.” The magistrate was still frowning. “What is that thing?”

He was gesturing to the camera, a cloth-covered lump in Triglav’s lap. The composer nodded to Triglav, who obediently removed the cover and peered down the telescopic lens at the squat, wind-whipped man sitting across from him.

“Please, not me,” said the magistrate, and rose to his feet. “I don’t have any.”

The composer was an expert in his field, so he could not ask for clarification.

***

The composer and his assistant showed up to the festival before anyone else did. They spent two hours photographing and recording and transcribing the gathering of wood by the young men of Sklep, who timidly darted back and forth from a thicket of birches to the field where they laid their kindling. At dusk, the boys lit a cluster of bonfires.

As the sky darkened, the people began to emerge from their houses. The girls wore white robes and had fern fronds braided into their hair; the children were barefoot. Everyone was shivering.

The composer made a note of the festival’s taxonomy: Christian alteration of a pagan summer fertility ritual. He stood at the front of the crowd, beside a birch tree covered in ribbons and beads, and watched the girls shuffle into formation. In a few minutes they would sing, opening the sky, and rain would come to the village of Sklep. The last tribe had told the composer about this miracle so many times that he believed their stories must have some basis in truth.

No one asked the composer who he was or why he had come. No one spoke. After a while the composer saw the girls open their mouths in unison like they were singing, but no sound came out. He shut off his wire recorder. He watched their lips form words he couldn’t recognize, their throats rippling with effort, their chests rising and falling.

Meanwhile Triglav winked into the camera and shot photo after photo. Triglav must either be hearing sound or had expected not to hear sound. No one acted surprised by the silence. The composer felt deeply and profoundly uncomfortable.

The girls shut their mouths in unison. The one on the end exhaled heavily as though all of the not-singing had tired her. Without speaking, they formed a line and walked into the birches. The young men followed at a respectful distance, heads lowered. A boy of eleven or twelve tried to go with them, but his father restrained him. The boy made a little choking sound of frustration. When he saw the look on his father’s face, he fell silent.

As the last of the boys disappeared into the trees, the composer tucked his trousers into his socks and set out after them. The procession had split the woods like a part, pressing down the undergrowth. The path left behind was easy to follow, and no one stopped the composer or his assistant from following. Beside the composer, Triglav shouldered the camera and photographed the backs of the girls’ heads and the boys’ shoulders from between the birches.

They walked for close to an hour. A few of the boys played scuffed brass instruments. Chromatic scales in irregular minor keys. Melancholy, dirge-like music. The music had no discernible tempo, but the boys all walked as stiff and regular as soldiers. The composer made a note to ask whether they practiced the ritual beforehand.

The boys glanced nervously into the trees sometimes; the girls too, though with less fear on their faces. Things with rope-like arms and legs shifted in the branches but never came down. Slick sounds came from the canopy. Presently the procession came to the side of a thin black river. The boys put their instruments down, and the girls laid candle-topped wreaths of pine and yew branches on the surface of the water.

The composer put his notes away and watched the wreaths drift downstream. He could feel that something was going to happen. Beside him, Triglav made a small shuddering sound and laid the camera into the composer’s arms. The composer was surprised, but shifted to shoulder the burden. He watched his assistant join the village youth. For reasons that he would not be able to remember later, he did not call Triglav back to him.

The girls and boys paired off, Triglav beside a girl with a narrow, pointed face that reminded the composer of a fox. The composer watched as they opened their mouths in another soundless song. Triglav sang too.

When they finished singing, Triglav waded waist-deep into the river with the other boys. Ripples formed circles around them. They shivered with the cold. The composer wondered what he would name the concerto he wrote in honor of this ritual. He knew the villagers would drown the little decorated birch tree at the end of the festival. He wondered if they would drown anything else.

Snake-like things came from the middle of the river, the same wet spitting predators that had been in the trees. Legs twined around necks, obscuring faces. The composer already knew his assistant was gone before Triglav sank into the water.

***

The woman Magdalena was old and built like a boulder. She crossed herself when the composer came to the door, saying, “You can never be too careful during green week.”

In her little cottage, she served the composer a fist-sized hunk of black bread with soft curdish cheese. While he ate, she covered the windows and locked the doors. Twice she said a charm. He didn’t know the words but he felt their rhythm and knew they were holy.

When he finished eating, the composer took out a leather-bound notebook and a pencil. He had not asked Magdalena if she would share the village music with him; he had not yet spoken to her. He thought something wordless must have passed between them. Already she had made overtures to protect him from whatever spirits the rustics believed in. He was comforted, a little flattered. He was hoping he would not end up like Triglav, dead on the floor of the river.

“Do your people use modern notation?” he said first.

She blinked at him.

“The treble and bass clefs?”

“No,” she said. “We don’t learn our music, not the music you mean.”

“And which music is that?” He made a note: ritual music distinguished from other genres. Possible religious component to this.

“The music that killed your friend.”

“The music made no sounds. I thought it must be some kind of pageant, or spell, not—not music. And it was vocals only, no instrumentation. Is there a reason for that?”

“You couldn’t hear it?” She looked suspicious.

“No,” the composer said. “Should I have been able to hear it?”

“Hmmm,” said Magdalena.

“Do you make music like that?”

“I can,” she said. “But I don’t think I shall.”

“I’ll pay,” the composer said. For months his artistic failures had been haunting him; he had drifted in a sort of waking nightmare between concert halls and conservatories. He had been longing to make music as the rustics did in his homeland. Now he was wandering the earth like Cain, a mark of wonder on his forehead, trying to find what secrets were contained within the little villages long forgotten by the Poles and the Russians whose operettas were so popular. Civilization had no beauty any longer, he had told someone in a Viennese coffeehouse. He wanted to compose the wilderness.

Magdalena blinked sleepily. “But we are, as you say, soundless.”

“How can I train myself to hear you?”

“You cannot. Outsiders cannot.”

“And if I am not an outsider?”

The woman laughed from deep inside her throat. She took the notebook from the composer’s hands and laid it on the floor. The wire recorder, she regarded with suspicion but allowed to stay. “You do not want to become one of us.”

“Why not?”

She licked her dry lips. Her eyes kept darting from his face to the covered windows. Shadows were playing on the blankets she had used as makeshift curtains. “When you hear the music, you will not be able to live anywhere else. You will have to stay here.”

The other tribe used to say the same things when they taught him how to play their fiddles and pipes. The composer admired how romantic the people of the plains were. He took up his notebook and made a note: music of central ritualistic and cultural significance.

“While you live among us,” said the old woman, “always remember to listen for rain.”

The composer said he would. Satisfied with his first day of work, he returned to the stranger house in the middle of Sklep. The snake-like things moved in the trees above his head but he did not hear them, or pretended he didn’t. That night, he composed a mazurka on his fiddle. He lay in his bed with the burlap-scented pillow and listened for rain.

The bodies on the floor of the river shifted, and rain fell.

***

The villagers of Sklep rarely left their homes. Even the food-sellers were reluctant to set up shop. While they sold goose eggs and rye flour to the composer, their eyes roved the landscape nervously. Green week, he kept hearing. It was green week so everyone was afraid.

They were not an expressive people. They did not mourn the boys and girls whom they had lost in the ritual. The composer made a note: ritualistic sacrifices occur with regularity? No one spoke of the lost youth, or of the snake-like arms that had reached for them. Magdalena would not acknowledge that anything had been lost, when the composer asked her.

“They will come home. They have to sow their oats,” she said.

The composer sent for a pianoforte. He taught modern notation and scales to anyone who would listen. He composed nocturnes and sketches on his fiddle. He filled numerous notebooks with his observations on the popular music of Sklep, which was mostly ballads full of cruel women and their hapless lovers. Only boys sang the songs. The girls never sang. They sat knitting with their long white fingers. Their feet drummed rhythms on the floor. The composer sat with them and felt impotent.

Many nights the people retreated to the banyas, little wood bathhouses where strangers were not welcome. Boys hauled piles of hot stones from the hearth to the banya door, where their mothers and sisters stood waiting in goatskin robes. At last, the doors shut and flumes of steam rose from the banya roofs. The composer played lonely chromatic melodies on his fiddle and caught rain in a barrel. Twenty-two inches fell in the first week alone.

***

After green week ended, Magdalena washed the blankets that had covered her windows. She was hanging them to dry when the composer reached her house. While she fixed the blankets to her line with clothespins, the composer sat on a tree stump with his fiddle tucked underneath his arm. By now he had grown comfortable watching idly while she worked in the kitchen or the yard. He knew she would not want his help. He wasn’t made for that sort of work.

“You survived,” she said, and beckoned for him to follow her inside.

“Yes,” said the composer. He had been trained not to belittle the superstitions of the rustics. Their mouths and doors would shut as soon as he did. “I thought today we might work on some more transposition of the ballads.”

“No,” said Magdalena. “Today I will sing for you.”

The composer reached for his wire recorder, trying not to look as eager as he felt. He had seen how Sklep opened up when the threat of green week ended. Sellers called out to passersby without taking care to keep their voices low. Children went to and from school in noisy, gleeful throngs. Men walked tree-shaded roads without looking nervously above them. But Magdalena, the composer had feared, would stay closed.

The woman took a long sip of water and grunted to clear her throat. Her arms hung at her sides and her chin pointed to the ceiling. When she sang, she made no sound. The composer sat and listened, his wire recorder humming uselessly in his lap. Triglav would have photographed the woman’s open mouth, her squinted-shut eyes, her flared nostrils. Triglav was dead on the floor of the river. The composer remembered hearing the story of some German hack who wrote a piece made entirely of rests: four pages of silence.

Then, after a few minutes, sound began to come from the woman’s throat. She sang in an undertone as thin as eggshell. The pitch of her voice wavered like an instrument being tuned. The composer could not have imitated the sound on his fiddle or pipe or piano. He could not have described it with modern notation. He could only listen, holding the wire recorder to Magdalena’s open mouth and wondering if the device would even catch the sounds she made.

“Did you hear me this time?” she said, when she was finished.

“A little,” he said. “Are you trained to produce such sounds?”

“I am too tired for questions,” said the woman. “Please, go before the rain comes.”

The composer packed up his belongings. As he reached the door, the sky opened and rain poured down.

***

After green week, Triglav returned. He came out of the river with a wife and a lush, dark beard on his face. When he shaved, his skin was smooth as a child’s underneath. He would say nothing of what happened on the floor of the river. He moved like a sleepwalker.

Ewers of water rested on every flat surface in the small house that Triglav shared with his new bride. The table, the bookcase, the stove top, the porch steps were all covered. Triglav’s wife did not offer the composer anything to drink when he came. The composer was accustomed by now to the inhospitality of the people of Sklep, and took the liberty of filling his canteen from one of the kitchen table pitchers. He found the contents murky and sour, as if taken from still water.

“It’s not to drink,” said the wife.

The composer sat down and waited for Triglav to come home. His assistant’s wife sat down across from him. Occasionally she dipped a dishrag in one of the pitchers and patted herself down with the swamp water, wetting her face and neck and hair. The composer lifted the camera from his lap and took photographs; the way the girl craned her neck, he could see that she wanted to be admired. After a while he asked if she liked to sing. She told him she’d always thought songs were better left to people who didn’t have any in them.

“Any songs?”

“Any blood,” she said.

Triglav came in the door humming. He asked the composer if they could go fishing soon. He said, “Alida tells me we won’t have rain tomorrow.”

From beneath the wet rag draped across her face, Alida said, “There will be no rain until the stranger house is empty.”

Triglav said, “Does she think she can do that? Put us men under siege that way?”

“She’s unmarried,” said Alida. “Of course she can.”

***

At the side of the river, Triglav spoke in a low tone of what happened during green week. He said he remembered those days as a dream. He watched while his existence swam above him. He had no power to stop things from happening on the floor of the river.

The girls could breathe, could swim. The girls’ limbs got longer, their incisors jutted out from their mouths; when they kissed the boys who partnered them on the shore, it stung like salt rubbed in a wound.

He said the girls sang sometimes at night, the same ritual songs they’d sung at Cemuk.

“You can only hear those sorts of songs properly underwater,” Triglav said to the composer. “They make so little sound above the surface.”

The composer took out his notebook and made a note: damage to the inner ear necessary for ritual music to resonate as intended?

“I only wonder,” the composer said. “Why did you marry her?”

“What do you mean?”

“She almost killed you. She might still kill you.”

“Oh, that’s how things are in this town,” said Triglav. “Every woman sees her husband drowned before she marries him. All the girls are made like that. They have to be, or they couldn’t make the rain come.”

His assistant believed in the power of the ritual now; the composer made a note.

“This power she has over you, you don’t mind it?” he said.

“Of course,” said Triglav. “They have us underneath for one week, just one week, and then we have them for the rest of their lives.”

“Or they have you,” the composer said.

The air was hot, for the sixth month had come and the summer solstice was close, yet still Triglav shivered. He said, “You shouldn’t stay here any longer.”

“Why not?”

Triglav wouldn’t say. “We ought to get away from the river,” he said. “A bachelor is worth the same as a grave here.”

“What’s that?” The composer had never heard the proverb before.

“Nothing,” Triglav said. “Nothing. That’s just what we said underneath the surface.”

***

Magdalena was not inside her house when the composer next came to her door. Steam rose from the roof of her banya, so he determined that he would return in an hour; an hour passed and still she sat inside the bathhouse. Long into the night she remained. Every half hour, boys brought hot stones and fresh water to her banya door.

The composer did not question them, though he wanted to. No one in Sklep would speak to him since he listened to Magdalena sing. His music students stopped attending their lessons and his interview subjects made implausible excuses that the composer recognized for what they were: rejections, closed doors. At night he played Chopin’s Raindrop Prelude on the pianoforte. He remembered a story about how Chopin had written the piece after he saw a vision of himself drowned on the floor of a river, raindrops falling over him in a steady patter. The composer thought perhaps he could call the rain to Sklep if he played that prelude enough times. The sun could not shine while someone played Chopin well.

The villagers of Sklep were too reserved to openly blame him for their drought, but the magistrate did come once to the stranger house. The composer admitted him and then returned to the piano bench, continuing where he’d left off in the Raindrop Prelude. “You can leave this town,” the magistrate said, when the composer came to a rest, “whenever you want—perhaps you did not know?”

“Do you fear to be seen with me?” the composer said, dropping to the bottom of the piano as he came to the slow, solemn portion of the piece marked sotto voce. He could hear the rainfall especially well in this bit, the drops coming steadily down. “Will they cast you out too?”

“I fear starving more than I fear the wrath of any woman. The only thing she can do is what she’s already doing: not singing.”

The composer stopped playing and made a note: music a mechanism of social control.

“You believe there will be no rain if the girls won’t sing?” he said, returning to the piano.

“The girls? No. They are—needed. For what they are. For the blood their children inherit. But for now, Magdalena is the only woman who makes the rain come.”

“And when she dies?”

“Another woman will sing for Sklep.”

The composer had reached the prelude’s closing motif, a bright tentative passage like the morning after a storm. He played the last chords. He held them down for longer than the score prescribed. Without turning his head, he said, “That might be for the best, don’t you think?”

***

Magdalena was still inside her banya when the composer came to her house. Steam rose from the bathhouse in white shuddering waves, but still the air felt dry. For weeks there had been no rain. The composer knocked on the door twice, then waited. When she told him to come inside, he did.

Magdalena was wrapped in wet willow leaves, a rustling gray garment that covered her from chin to ankles. Her bare feet, pale and shriveled with water, sat propped on one of the wooden benches affixed to the walls. Her wet hair was bound with fern fronds and hung down her back in heavy bundles.

“I want you to bring the rain,” said the composer.

“No,” said Magdalena, and rose from the bench. The willow leaves crackled softly when she moved. Outside, the wind picked up.

“You won’t?”

“No,” she said. “Not while an outsider stays in the stranger house, banging on foreign instruments and writing songs that sound like bad copies of the ones we sing at Cemuk-time.”

“You refuse?”

“Leave Sklep.”

The composer understood. The crops were wilting in the fields. The river had gone down so far that the Sklep river-girls swimming along the floor were visible from the bank. The trees were as bare as they were in wintertime. Even bathhouse wood couldn’t retain its moisture. Even the wettest things had become perilously dry.

***

Everyone knew who burnt down the banya with Magdalena inside. They also knew when the banya burnt, because the first rain in weeks fell in time to put out the last of the flames.

Sometime later, when he had left the stranger house and taken a wife of his own among the village people, the composer asked Triglav’s wife, the new rain-bringer, to sing for him. She did, in a cool, sonorous undertone that made each note sound like a secret dropping from her lips. The composer could hear her perfectly.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Matyóland 1. Some says, the „matyó” people are the descendants of King Matthias’ Magyar bodyguard, but the nickname actually can have other origins too. „Matyó”s live in a few villages around Mezőkövesd in Borsod county. Mezőkövesd is the „heart of the Matyóland”, but the nearby Tard and Szentistvánare also notable settlements of this unique group of Hungarians. They belongs to the same ethnic group, as the „palóc” people, though the „matyó”s are strictly catholics as for religion, while „palóc”s are protestants. If the origin of their name really goes back to King Matthias, it can be also true, that their characteristic folk art was inspired by the Gothic-Renaissance styles of Matthias’ court. The magnificent costumes of the women, with lines of almost gothic delicacy, are richly embroidered. Though they use vivid colours as well, the aristocratic combination of white on black is the favourite. The women present a tall slender figure in their ankle length skirts, which flare out slightly at the bottom . The rich and colourful motives were designed and sketched by so-called “writing” (i.e. drawing) women, who wove the various flowers – most favored roses - of their gardens into their clothing. „Matyó” embroidery began to hit its prime in the 1860s and 1870s. This era brought the “festive room” to life, as houses were decorated with painted furniture, enamel plates, jars, bowls and high, richly decorated beds.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, Molly

Molly Picon stopped growing when she was a kid and topped out at around four foot eight -- four-eleven standing on her tiptoes, she liked to say. The biggest thing about her was her impish Betty Boop eyes. But she packed a lot of energy and spirit into that miniature package. She could and would do anything to amuse an audience -- sing, dance, do a somersault, climb a rope, crack jokes, wear blackface or boy's knickers. She played gamins, waifs, soubrettes well into her matronly years. The one thing she wouldn't and maybe couldn't do was to hide or even just tone down her essential Jewishness to appeal to the goys in the mainstream audience. It sets her apart from many other Jewish entertainers of her day. Whether she was performing in Yiddish or English, on Second Avenue or in Hollywood, there was never any question that Molly Picon was Jewish. Very Jewish.

She was born Malka Pyekoon on the Lower East Side in 1898, in a fourth-floor back bedroom of a tenement on Broome Street near Bowery. Her mother was a seamstress who'd escaped the pogroms near Kiev as one of a dozen children. Her father was an educated man from Warsaw who was never happy doing an immigrant's menial labor in America, so he did as little as he could. He also turned out to have a previous wife back in Poland he'd never legally divorced. He drifted in and mostly out of Molly and her sister Helen's lives. Decades later, when Molly became well-off and world famous, he'd drift back into hers, to borrow money.

Their mother and grandmother picked up and moved the girls to Philadelphia, where Mom became a seamstress at a Yiddish theater and took in boarders. Later she'd run a small grocery store. The story of how Molly got her start in show business -- like many of the tales in her charming and irrepressibly schmaltzy memoir Molly! -- is too good not to be true. When Molly was five her mother, who made all her daughters' clothes out of odds and ends, stitched her up a fine outfit and took her on a trolley headed for amateur night at a burlesque theater, the Bijou. On the trolley a drunk challenged the little girl to show him her act. She sang and danced in the aisle. Charmed, he passed the hat and collected two dollars. At the Bijou the audience tossed pennies on the stage while she performed. She also won the first prize, a five dollar gold piece. Her grandmother was astonished at the ten dollars she'd earned -- roughly a week's wages for an adult worker. When her mother said she was going to start taking her around to all the amateur contests, her grandmother said forget the theaters, there weren't enough in Philadelphia -- just keep taking her on the trolley.

Boris Thomashefsky's brother Mike ran Philadelphia's Columbia Theatre. He soon put Molly and Helen in a Yiddish production of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Helen as Little Eva, Molly in blackface as Topsy. Molly, billed as Baby Margaret, continued to act through her childhood. She dropped out of high school in 1915 to tour small-time vaudeville in a female quartet, the Four Seasons. In Boston in 1918 she visited a Yiddish theater group who performed one night a week at the Grand Opera House, a large but no longer grand theater in the South End that staged wrestling and boxing the rest of the week. One of the young actors she met there was Muni Weisenfreund; ten years later he'd go to Hollywood and become Paul Muni.

Jacob Kalich, who ran the theater company, came (like Weisenfreund) from Galicia, a province on the Austro-Hungarian empire. He'd studied to be a rabbi but then fell in with traveling Yiddish theater troupes. He'd slipped into America without a passport and speaking no English in 1914. Kalich hired Molly away from the Seasons, they fell in love and were married the next year in the back room of her mother's grocery store. According to Molly's memoir, her mother stitched her wedding gown from a stage curtain.

Yonkel, as Molly called Kalich, wrote parts and whole plays specifically for his new wife. One was Yonkele, an operetta in which she wore boy's clothes and sang, danced and did her somersaults as a kind of Yiddish Dennis the Menace. Kalich was unsuccessful in trying to get one of the Yiddish theaters on Second Avenue interested. On the Lower East Side as in American theater generally, leading ladies tended to be stately Lillian Russell grandes dames, not petite gamins in knickers.

After a child was stillborn in 1920 Kalich distracted Molly with a new project. They sailed for Europe. His plan was to make her a star (and improve her Yiddish) in the theaters there, then return in triumph. They started in Paris, where Yonkele was a hit, then toured it around Europe for two years. In her memoir she says they did three thousand performances, almost surely an exaggeration, but they did keep busy, and her star kept growing. She made her first Yiddish-themed silent films in Vienna starting in 1921, playing a sassy soubrette or a boy. When they were in Bucharest hundreds of university students shouting anti-Semitic slurs rioted in and outside of a theater where she was performing. They may have been put up to it by the Romanian National Theatre, which was losing business to Picon. It was time to come home.

Jews around Europe had been writing their American relations about the wonderful new star. Kalich's plan had worked. By 1922 the Second Avenue Theatre near Second Street was happy to host Yonkele and anything else Kalich put together, as long as it had Picon in it -- Gypsy Girl, The Circus Girl, Schmendrick, Oy is dus a Madel (Oh, What a Girl!). Picon played to houses packed not just with Yiddish-speaking Lower East Siders but with celebrities like Greta Garbo, Mayor Jimmy Walker, Albert Einstein and D. W. Griffith. Griffith was on the downside of a long career by then and tried, without success, to raise money for a film starring Picon. Flo Ziegfeld and his wife Billie Burke (the good witch in Wizard of Oz) came over from Broadway to see Molly perform. Afterward, Yonkel and Molly took them to a Jewish restaurant, where the waiter covered the table with plates of pickles, sauerkraut, fried steak, radishes slathered in schmaltz. The very goy Burke asked the waiter if she might have some vegetables. What, he snorted, pickles and sauerkraut aren't vegetables?

Picon was such a star that Kalich got the idea of renaming the theater the Molly Picon Theatre. When their packed performance schedule there permitted, they toured Yiddish theaters around the country. Later, Jews who had fled Eastern Europe for South America organized a tour for her there. She would also tour South Africa.

She returned to vaudeville in a big way, headlining at the Palace in Times Square with Sophie Tucker. Picon sang half her songs in English, Tucker sang half of hers in Yiddish, and they triumphed. When Picon played the Palace in Chicago, Al Capone (who had started out on the Lower East Side himself) bought out the first three rows. After the show he took Picon and Kalich out to dinner. At his request she sang "The Rabbi's Melody" (a big hit on Second Avenue) and, she claims, he "cried like a baby." For the rest of her career she introduced it as "the song that made Al Capone cry."

The crash of 1929 ruined Picon and Kalich along with everybody else. They scrambled to get back on their feet. They took over the grand Yiddish Art Theatre on Second Avenue and renamed it Molly Picon's Folks Theatre. In 1936 she and Yonkel sailed back to Europe to film a Yiddish musical in Poland, Yidl mitn Fidl (Yidl with a Fiddle). She plays a penniless girl who disguises herself as a boy to join a band of traveling musicians. Location shooting took place in Kazimierz, the once grand, now bedraggled Jewish zone in Krakow. They recruited the whole neighborhood as extras for a big wedding scene that took days to shoot. Few if any of the locals, deeply Orthodox and very poor, had ever seen a movie. They marveled at the food that kept appearing as scenes of the wedding feast were shot and reshot.

Yidl was a hit with Yiddish audiences worldwide. It inspired one of Hollywood's great eccentrics, director Edgar G. Ulmer, to shoot a couple of his own Yiddish films in America. Ulmer, another Jewish immigrant from the Austro-Hungarian empire, had started his career in Hollywood directing the 1934 Karloff-Lugosi vehicle The Black Cat for Carl Laemmle's Universal Pictures. On the set he met and stole the wife of one of Laemmle's nephews, for which the mogul reputedly banished him from Hollywood. Ulmer drifted to New York. When he saw Yidl drawing big crowds on Second Avenue he started a small Yiddish production company, Collective Film Producers, and filmed Grine Felder (Green Fields), recreating the shtetl in a field in New Jersey on a shoestring budget. Ulmer spoke no Yiddish himself, so he hired the Second Avenue star Jacob Ben-Ami as co-director and go-between with the cast of Second Avenue actors. The movie went on to be one of the most praised in the history of Yiddish film. (Ulmer later went back to Hollywood and a now-celebrated career as a Poverty Row maker of lowest-budget B's, ranging from brilliantly idiosyncratic noir like Detour to zero-budget sci-fi like Beyond the Time Barrier.)

As the 1930s drew to a close, Picon and Kalich saw that they were playing to the same dwindling and aging audiences over and over. Yiddish was dying out among the American-born children of immigrants, taking Yiddish theater with it. Although they would continue to work on Second Avenue through the 1950s, Picon still playing Yonkele in her fifties, it was clear they needed to work harder to crack the mainstream.

In 1940 she took her first serious roll on Broadway in Morningstar, a short-lived and soon-forgotten drama notable mostly for her spot in it and that of a thirteen-year-old actor named Sidney Lumet. In 1942 she returned to Broadway with a big gamble, her and Yonkel's musical Oy Is Dus a Leben! (Oh Is This a Life!), the first Yiddish play on Broadway. It was a vanity piece about Molly's life and their marriage, and they played themselves on stage. The Al Jolson Theatre -- where Jolson had taken thirty-seven curtain calls on the opening night of the revue Bombo in 1921 -- was renamed the Molly Picon Theatre for the occasion. The Times' Brooks Atkinson (who later got a theater named for him, too) caught the opening night, when the house was packed solid with fans and Molly pulled out all the stops. They adored her; Atkinson, who was as goyish as Molly was Jewish, thought she overplayed and mugged for them too much, coming off "gauche and coy." Atkinson was the most powerful theater critic in New York at the time, and his reviews made or broke plays. But his tepid response to Oy Is Dus a Leben! couldn't overpower Picon's appeal with Jewish audiences. The show ran for a respectable seventeen weeks, and she claims it only ended when the producers, feeling that they'd shown it to every Jew in New York by then, decided to quit while they were ahead.

During World War Two Picon did many USO concerts, played every military base she could get to, joined in many all-star benefits for refugees. She stands out in a very brief and uncredited scene in The Naked City, the 1948 cop movie inspired by Weegee's book. She runs a soda fountain at the corner of Norfolk and Rivington Streets. "Got any cold root beer?" a detective asks her. "Like ice!" she replies, then goes into a bit of endearing Yiddishe mamele schtick. After that, while she remained very busy on stage and did some tv, there was nothing much from Hollywood until 1963, when she played Frank Sinatra's mom in the screen version of Neil Simon's Come Blow Your Horn. When Frank had signed on they changed Simon's Jewish family to Italian to accommodate him. Then they hired Picon and changed it back to Jewish. This turned into a problem for Lee J. Cobb, who played the father despite being just four years older than Frank; they gave Cobb old man make-up to age him and put a wig on Frank to make him look younger. Cobb was Jewish, born Leo Jacob in the Bronx, but he hadn't played Jewish in years. He had to relearn it. It's not a good movie but it was a box office success and Picon earned an Oscar nomination for her performance.

In 1961 she was in another hit on Broadway, Milk and Honey, a Jerry Herman (Hello, Dolly!) musical comedy about a busload of Jewish widows from America trying to find new husbands in Israel. She was in her early sixties, but still managed to work a somersault into the part. When she left the show to go film Come Blow Your Horn, Hermione Gingold replaced her.

Then Fiddler on the Roof opened on Broadway in 1964. It was a record-setting hit that ran until July 1972. Picon was not in it. The role of Yente the matchmaker went to Bea Arthur. But when Norman Jewison -- not himself Jewish, despite the name -- put together the cast for the 1971 film adaptation, he studied Yidl mitn Fidl for background and hired Picon for Yente. Inarguably the schmaltziest Hollywood film ever made about Jews, it was the perfect setting for her and remains the role she's most known for today.

After Yonkel died in 1975 she gradually withdrew from the public eye, puttering around in their home up the Hudson, which they'd named Chez Schmendrick. She wrote her memoir, did a little more tv (Grandma Mona on The Facts of Life) and a couple more movies (Mrs. Goldfarb in The Cannonball Run and Cannonball Run II), and in 1979 toured a one-woman show, Hello, Molly! But her own health was deteriorating. She lived her last decade quietly and was ninety-three when she died in 1992.

by John Strausbaugh

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

you mentioned that you don't post photos of the szlachta (this is a great site btw.. not complaining! just inquiring).. but you posted pictures of costumes from zywiec.. my grandparents are from there, and as far as I know the local costume is that of highlanders (vlach inspired).. the people who dressed like those pictures were non-highlander szlachta themselves (usually krakowiaks). Or am I getting my history and regionalism wrong? Although they did have a unique regional costume though.

Hello there! Let me try to explain it step by step for everyone because it’s all connected in a way :)

It’s true that I don’t post the clothing of szlachta here. For those of you who didn’t see my old replies, let me just remind and specify that what I’m showing here is the festive clothing of the common people / peasants / lower classes, that are all classified under the Polish definition of ‘stroje ludowe’, and in this case ‘lud’ would be the something along the lines of a ‘layer of society living predominantly from manual labor, in the past consisting mainly of the rural population’.

Meanwhile, the szlachta clothing is a historical garment or period clothing that was worn by the nobility in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth around the 16th-17th centuries. Time-wise, the typical szlachta clothing doesn’t even overlap with the folk costumes I’m focused on. It’s because majority of the Polish folk costumes (in the form we know them nowadays) came only from around the turn of 19th/20th centuries, and were ‘created’ after abolition of serfdom. Before the abolition, most of the peasants were even forbidden to wear some certain elements of garment.

19th century was an interesting time period for the Poles, as the country was invaded and wiped off the maps. It also makes the whole szlachta clothing a bit more complicated. By the mid-18th century, the old szlachta fashion had been basically long gone. However, during the difficult 19th century it was revived as a symbol of the old nobility from the golden era of the Commonwealth. Some men from the upper classes started wearing it as a form of protests and a political symbol, particularly around the times of uprisings. What they wore was however a simplified version of the old fashion.

In the 19th century the revived szlachta fashion influenced the peasants and townspeople as well, for slightly different reasons. Now that they were allowed to wear whatever their budget allowed them to (in the case of peasants thanks to the abolition of serfdom I mentioned above), some of the folks were getting 'inspired’ by certain elements of the revived szlachta clothing, particularly among patriotic communities.

It was a similar case with the male Żywiec costume that is described as a continuation of the old szlachta clothing and of the Polish townsfolk’s historical costumes. There are many differences though. For example, the ‘kontusz’ in Żywiec costume is much shorter than the original kontusz of szlachta. Or, as an outerwear Żywiec uses a ‘czamara’ which was originally inspired by Hungarian coats, and was popular among Polish townspeople in 18th century.

Now, I must specify that the Żywiec costume is a costume of the rich townspeople from the town of Żywiec. What you mentioned in your ask is a costume from villages surrounding that town, worn by Górale Żywieccy and classified as the Beskid Żywiecki costume (costume from some parts of the Żywiec Beskids mountain range).

I hope it makes it a bit more clear to you :)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

@captainwordsmith thank you for the question! :D

!DISCLAIMER! Nothing of this is set in stone... since i’m not producing for an official comic or TV show, i keep myself the freedom that i can sometimes change things up if i find a better design idea.

For any history/fashion buff reading this, I’m really sorry if i name things wrong xD this is more about what i’m looking for when i look up references, but i always also change things up or combine them.

So, since the seven kingdoms are loosely based off europe, i always thought it a given that the fashion in them is different from region to region :D When i look at a character or house i get like... an idea in my head, and i try to finetune research until i find the real life fashion that mirrors it. While i always name a country it’s never really 100% consistent since i’m not making accurate historical art... i always mix it around with several influences/time periods, and im more about getting a look that’s semi-consistent in itself than a look that’s necessarily consistent with a historical period. after all im trying to make fashion for a fantasyland... So this is more of a list of what stuff i look up when researching.

Also, unless speciifed, if i say a country’s name i either refer to folk clothing, or medieval fashion and up to the 16th-17th century.

The amount of info is based on how often i draw the people from the region, so sometimes a lot, sometimes very little (yet!).

There’s also my pinterest wall where i collect references, nothing i uploaded myself just stuff i favourited from browsing the site

The North

The North makes me think furs, and clothing from solid materials. My mental image is always primarily slavic countries, but with added scottish and scandinavian influences since it’s a huge region and should have differences in itself.

House Stark: Since they are the main northern house and have many important characters, i try to give them a more standard "fantasy” appearance; they are kind of like an introduction to both the north and the series itself, so while i want to already start with the furs and all, i still like to kind of keep them like the readers and show watchers would expect. though i saw a really rad polish eddard and it makes me want to up the slav with these guys

House Karstark: what i would call “high russian”... I don’t really have a deep reason for this it is just the mental image that immediately springs to my mind. Maybe their sigil reminds me of that aesthetic

House Bolton: Elegant clothing, not too fancy but not conservative either. I first kind of got an idea for their vibe when i saw someone describe roose as “westeros’ vlad the impaler”; so usually when i look for references i try to stick to romanian and hungarian clothing, and stuff that fits in with that fashion; The dreadfort lies in the east, so hungary/romania/ukraine seems fitting to me.

House Ryswell: Very loosely scottish influences... also for the women, 14th century french/german vibes

White Harbor: They migrated there from the south, so i try to give them a more “southern” fashion (ie fashion that does not look like the rest of the north). Influences from france/italy, and netherlands.

House Umber: Vaguely russian, but not very elaborate. Kind of simple, big, warm, clothing (they are the closest to the wall), but with those cool hats.

House Dustin: Pretty celtic, invoking an idea of “the first king”. Maybe a king arthur vibe added... normannic...

Riverlands

When i read descriptions of it, i always think germany... Green, with a river through it, and medium climate...

House Frey: really vibe me as german, flemish or dutch, so that’s kind of what i’m going for with their clothing. Also some 16th century influences, i often see paintings in museum’s where im like “thats walder!!”

also these hats

House Tully: Kind of a conflict with the german/dutch thing i want to have going on, but the name is irish and they have red hair so irish fits... usually a case by case decision how i mix it

Vale

this is hard to specify because i can’t quite name what exactly im seeing in front of my inner eye... It’s this sort of, really medieval style, maybe 12-15th century, influences english and german?

The eyrie is so far up and kind of magical seeming, it reminds me of a fairy tale... so that is the vibe im slightly trying to achieve, this innocent medieval vibe you get from history books geared at kids. Maybe also sort of a king arthur feel.

Obviously neighbour to the riverlands so it can have similar fashion at times... exchange of trends....

And since It’s near Essos we can also look at cultural exchange there. It would make sense if a vale lord or two had mixed heritage...

House Royce: Their seat is runestone, and runes are on their sigil, so maybe these crowns... or some fantasy dwarf elements... Also general celtic influences (very vague and i WILL research more about celts when i actually draw members of this house). Hope when i research, that i will find a good idea on how to differentiate to two cadet branches well.

Westerlands

House Lannister: I’m seeing the Lannisters as like, really hip english and french fashion. You know the awesome hats, and beautiful dresses... The hair up in this horn-like headgear... jewels and ornaments...

Not so sure on the rest of the westerlands houses since i don’t “see” the characters around as much, i didn’t form a good impression... But I’m thinking solid english/french folk. Not the same as the ryswells, more of a rennaissance flair.

The Reach

House Tyrell: something in me wants bosnian Tyrells... The way the reach’s described in Dunk&Egg makes me think of my summers there, and they have brown hair/brown eyes. Though realistically (as in, what seems intended by grrm) i’m getting a huge french vibe (highgarden like those french gardens), so i’d strive for a good mix. I just need to differenciate it from the Lannisters, probably by keeping the mediterranean influence strong.

House Hightower: Burgfräulein vibes

Crownlands

Nobility/King’s Landing: Should scream “king’s court”, im thinking just the coolest looking medieval fashion i can find. A bit more modern, rennaissance-y, maybe. And stuff like this

House Targaryen: very boring but whatever the influences for LotR elves are, plus generally european kings, those with all the drama that martin was inspired from... i will need to work out something right proper for future targ drawings tbh

Dorne