#early modern english history

Photo

ROBERT AND ELIZABETH’S ARGUMENT

Becoming Elizabeth 1.03 Either Learn or Be Silent

Requested by @aethelreds

#becoming elizabeth#becomingelizabethedit#jamie blackley#alicia von rittberg#elizabeth I#robert dudley#elizabeth tudor#robert dudley earl of leicester#perioddramaedit#periodedit#period drama#weloveperioddrama#userbennet#userperioddrama#onlyperioddramas#perioddramasource#early modern history#early modern english history#tudor#tudoredit#tudors#tvgifs#tvedit#tvfilmsource#tvfilmedit#tvfilmdaily#tvfilmgifs#tvfilmcentral#katherynparr#aethelreds

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Modern English: Shakespearean Era to the King James Bible (1500-1700 AD)

Early Modern English is the linguistic epoch that spans roughly from the late 15th century to the late 17th century. It represents a significant transitional phase in the evolution of the English language, bridging the gap between the Middle English period and the modern form of the language that we use today.

During the Early Modern English period, several key developments profoundly influenced…

View On WordPress

#Cultural exchange in language#Early Modern English history#education#English#English language evolution#English vocabulary enrichment#english-language#english-learning#Exploration and language evolution#Grammar changes in Early Modern English#inglés#King James Bible influence#King James Version impact#language#Language during Renaissance#language-learning#languages#learn-english#learning#Linguistic developments 1500-1700#Printing press influence#Renaissance language transition#Shakespearean era language#Standardization of English#William Shakespeare vocabulary

0 notes

Text

current mood: eternally annoyed by people who refer to the variation of English spoken in the medieval era as “Old English.”

#That’s not Old English#Old English would be completely unrecognizable as English to those who don’t know it.#What you’re referring to is usually Middle English#Or Early Modern English.#Old English again would be completely unrecognizable as English to the vast majority of people today.#It was very very very different#There were entirely different letters and sounds that no longer exist#E.g. wynn; eth; thorn; æ#Sorry I’m on mobile and don’t have my Old English keyboard installed on here#You also had diphthongs and different monophthongs and! I could go on#history#Old English

811 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miniature wedding portraits of Frances and John Croker of Barton by Nicolas Hilliard, circa 1581.

#freckles#early modern#early modern era#early modern period#english renaissance#english#renaissance#cool#portraits#portrait#painting#paintings#wedding#romance#love#couple#marriage#romantic#pretty#handsome#aesthetic#academia#history#fashion history#fashion#style#interesting#nicolas hilliard#elizabethan#tudor

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question : Murder and Disappearance Edition I

Given that Judge Crater, Roanoke, and the Dyatlov Pass Incident are credibly solved, though not 100% provable, I'm leaving them out in favor of things ,ore mysterious. I almost left out Amelia Earhart, but the evidence there is sketchier.

Some people were a little confused. Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury are the Princes in the Tower.

#Time Travel#Famous Murders#Jack the Ripper#La Bete du Gevaudan#Gandillon Family#Werewolves#William Rufus#King William II#Edward V#Richard of Shrewsbury#French History#English History#Early Modern Europe#Victorian England#Lord Darnley#Mary Queen of Scots#Scottish History#Amy Robsart#Lord Dudley#The Sodder Children#The Somerton Man#Australian History#Prime Minister Harold Holt#Elizabeth Short#The Black Dahlia

490 notes

·

View notes

Text

✧ "Elizabeth of York's responsibilities included acts of charity, keeping her household, and, of course, bearing heirs. As the queen of Henry Tudor, she had the additional charge of demonstrating support for him that would help unite the country and end the infighting between Lancaster and York. To this end, each appointment and gift had to be considered for the impression that it made. From the beginning of their marriage, Elizabeth accepted a submissive role, seeing it as her duty to God and country to support her husband.

Henry and Elizabeth agreed that her first concern was for children, and they were almost immediately blessed with their first. Prince Arthur was born a scant eight months after their marriage, so Elizabeth’s time as queen coincides with her time as a mother. Even before Arthur was born, she would have begun planning for his education and household. Elizabeth spent significant time directing the care of her children and participating in their life herself much more than many queens of her era. Still, her priority was Henry, and the two were seldom apart, even after separate households were set up for the children." — Samantha Wilcoxson

Jodie Comer as ELIZABETH OF YORK

in The White Princess (2017)

#elizabeth of york#henry vii#house of tudor#house of york#english history#history#tudor history#early modern history#15th century#historyedit#twpedit#the white princess#period drama#queens#thewhiteprincessedit#our gifs#our creations

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harquebusier Armour from England dated to about 1680 on display at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, Scotland

During the 17th century harquebusier cavalry were some of the most common in European armies. They were named after the carbine musket they used, the "harquebus" a shorter musket than the ones used by infantry. By 1680 though the Royal Scottish and English armies (later unified as the British Army) were converting these units in regiments of dragoons, mounted infantry who could also charge as cavalry. The armour was phased out of British cavalry regiments by the time of the 18th century.

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#armour#fashion#17th century#british empire#early modern period#england#english#military history#cavalry#kelvingrove art gallery and museum#glasgow#barbucomedie

111 notes

·

View notes

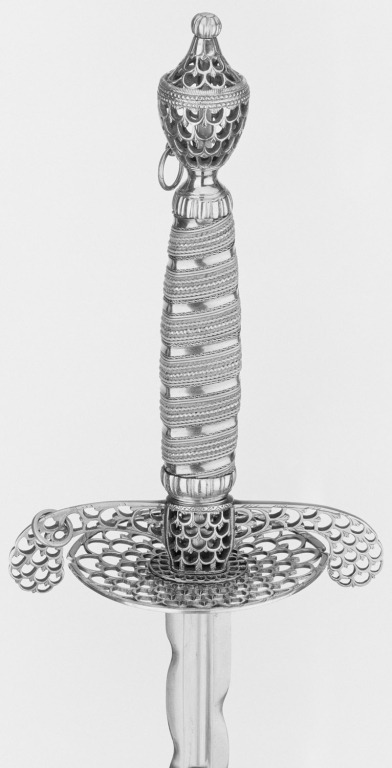

Photo

A flamberged Smallsword with a delicately pierced hilt,

OaL: 39.5 in/100.25 cm

Blade Length: 32.1 in/81.5 cm

England, ca. 1670-1787, housed with the Royal Collection Trust.

#weapons#sword#smallsword#europe#european#britain#british#england#english#early modern#royal collection trust#art#history

459 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love how discussion of "medieval" fantasy novels had me half convinced the divine right of kings was a medieval concept even though I've never come across it in medieval literature, and then I start doing some actual research and discover we can blame that one on James I and the seventeenth century.

Edited to add: I turned off reblogs for a reason, lads. I realise there's a lot more nuance to the history of this phrase than I conveyed here and that versions of this concept have existed in different places. I was talking about a very specific manifestation of it in a very specific (English) context, in terms of how it gets used in popular understandings of the past – nothing else, and purely as a curiosity for myself, not a history lesson or discussion starter. If I could also turn off replies on this post, I would do so. Please stop telling me about the use of the concept elsewhere and during other periods, I am a) aware and b) not actually interested at this time. I have made that abundantly clear in my comments on the post.

#once again a popular idea of the medieval world turns out to be early modern#also if you're wondering why i am just now learning this for the first time: look i am not a historian#my knowledge of english history runs 450-1066 and then stops again until 1900 okay#history#the problem of kings#me: is it anachronistic for my medieval king not to believe in the divine right of kings?#the actual academic history book i'm reading: buddy it would be anachronistic if he DID#considering he probably got elected

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vanessa Bell (British-English, 1879-1961) • The Tub • 1917

Vanessa Bell was an English painter and interior designer and prominent member of the Bloomsbury Group in the early twentieth century. She focused on Post-Impressionism and Abstraction in her art. “The Tub”, painted in 1917, is an unusually large work that was originally intended for the garden room of her new house. However, it was never installed and remained folded up until its rediscovery during the Bloomsbury revival in the 1970s.In this captivating piece, Bell follows the tradition of several French painters, including Degas, Matisse, and Bonnard, who depicted women during their toilette. The painting predominantly features yellow ochre and a greenish grey color palette.

#art#painting#fine art#art history#vanessa bell#british artist#woman artist#english painter#painter#art nude#oil painting#modern art#early 20th century british art#bloomsbury group#post impressionism#pagan sphinx art blog#art blogs on tumblr#art lovers on tumblr

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

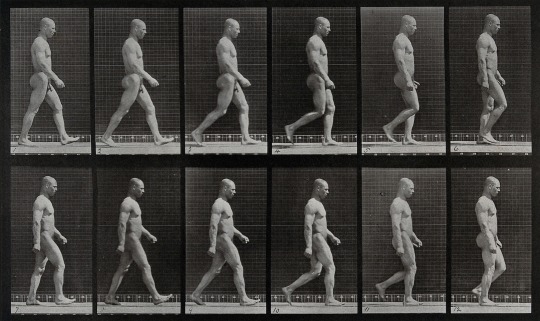

Two men boxing, Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887

A man walking, Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887

Man running, Plate 7 from Animal Locomotion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1887

#eadweard muybridge#English photography#English photographer#english art#english artist#photography#vintage photography#early photography#motion photography#aesthetic#beauty#male physique#male nude#british artist#british art#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

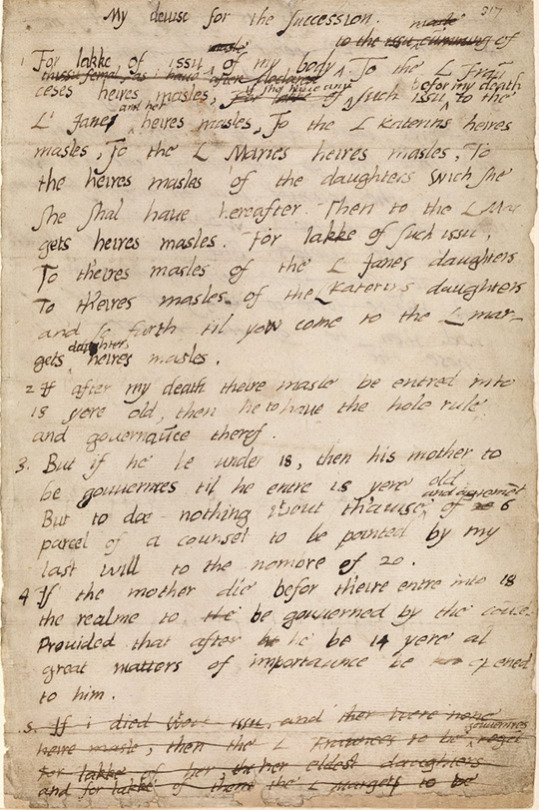

TUDOR WEEK 2022

DAY 4 FAVORITE TUDOR RELATED RELIC → (2 OF 2) EDWARD VI’S DEVISE FOR THE SUCCESSION.

When King Edward VI fell seriously ill in 1553, he and his councilors began to put the kingdom’s affairs in order. The priority was the succession as he did not have any children himself and his heirs at the time were his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth. Mary was the primary heir, but she was devoutly Catholic. Strongly opposed to having England fall into Catholic hands, Edward drew up the “Devise” changing the succession from his half sisters to the children and grandchildren of Mary Tudor (Henry VIII’s younger sister) and Charles Brandon. Once this change was put in place, the primary heir was Lady Jane Grey, Edward’s first cousin once removed (granddaughter of Mary Tudor, grandniece to Henry VIII). This fulfilled the religion issue, as Lady Jane Grey was passionate about the Protestant religion. Lady Jane Grey did succeed to throne, but was deposed by Edward’s sister, Mary, nine days later.

Portrait: Edward VI by William Scrots

Devise Image: Inner Temple Library

#tudorweek2022#dailytudors#edward vi#devise for the succession#tudoredit#tudorerasource#artedit#portrait#16th century#early modern history#early modern english history#tudor history#historical letter#historical documents#henry viii#lady jane grey#history#historyedit#mary I#elizabeth I

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

After Oliver Cromwell's death was the Commonwealth doomed, because of structural factors, or a republic like the United Provinces could have survived but it failed because of contingency and individuals' actions? How guilty is Cromwell for not setting solid foundations for the continuity of the Commonwealth?

Yes, the Commonwealth was doomed after Cromwell's death, but the reason why is both structural factors and contingency/agency - because the actions of a few individuals (including but not limited to Cromwell) set those structural factors in motion.

In term's of Cromwell's guilt, I would say that he bears ultimate responsbility for the institutional weaknesses of the Commonwealth. To be totally fair, he did try to fix those weaknesses repeatedly - but because of the actions he took at the beginning that set up the structural factors in question, those efforts came to naught.

That's the TLDR, I'll do the specific explanation below the cut, because it's going to go long.

Background

Just to make sure everyone's on the same page: in 1640, Charles I is forced to call Parliament even though he hates doing it. He dissolves Parliament after three weeks. (Hence why it's called the Short Parliament.) He's then forced to call Parliament again, and this Parliament is the Long Parliament. The Long Parliament enacts a whole series of legislation that Charles I hates, and then in 1642 the conflict between King and Parliament breaks out into the First English Civil War (1642-1646).

During this first phase of the conflict, it takes a while for Parliament and the Parliamentary generals to get their act together. Things begin to turn around in 1644 when the Scottish Covenanters join the war on Parliament's side and they win the Battle of Marston Moor - which gives Parliament control of the North of England and is the first battle where Cromwell plays a major role. The next year, Parliament gets rid of the original Parliamentary generals through the Self-Denying Ordinance, forms the New Model Army under Fairfax and Cromwell (the one guy specifically exempted form the Self-Denying Ordinance), and Fairfax and Cromwell go on to completely destroy the Royalist armies at Nasby and Langport.

Charles hangs on for a bit, but is eventually captured in 1646 and the first Civil War ends. The question is now: what do we do, now that Parliament has won?

The Putney Debates

Once the fighting was over, the political fighting could begin and it was quite complicated. You had the Long Parliament, which was dominated by the moderate "Presbyterian" faction who had been locked out of military power by the Self-Denying Ordinance. You had the New Model Army, which was religiously Puritan but split politically (more on this in a second). You had the Scots, politically constituted by the Scottish Parliament and militarily represented by the Covenanter armies, who wanted Presbyterianism to be extended throughout Britain. And then you had the Royalists and Charles I, who were usually but not always the same faction.

I'm going to focus here on the part of this conflict that involved the Long Parliament and the New Model Army. The Long Parliament wants to do a deal with Charles I - although the problem is that Charles is stretching out negotiations in the hopes that if everything collapses into anarchy he might get himself back on the throne - it wants a unified British Presbyterian Church established (because it had kind of agreed to set one up as the cost of getting Scottish support during the war), and it wants to get rid of the New Model Army which it views as dangerously radical and way too powerful.

The New Model Army isn't sure what it wants, because it's split between the Agitators (i.e, the Levellers) and the Grandees (the senior officers of the Army, led by Cromwell and Fairfax) - although the one thing both sides agree on is that they're not going to accept a single established Presbyterian Church and that they aren't going anywhere until they get their back pay and some sort of reforms happen that justify four years of civil war.

In the mean-time, everyone's getting very testy. First, the Long Parliament orders the New Model Army to disband in early 1647. The New Model Army refuses to disband. Then the New Model Army takes control of the prisoner Charles I in early June. In late June, a pro-Presbyterian mob invades Parliament calling for an established Presbyterian Church and for Charles I to be brought to London, causing all of the Independent (i.e, Puritan) MPs and the Speaker to flee the city and seek the protection of the New Model Army. Then in August, the New Model Army marches on London, and forces Parliament to enact a Null and Void Ordinance undoing everything the Long Parliament had done since June, which causes the Presbyterian MPs to withdraw from Parliament (temporarily), which means the Independents are now in the majority.

All of this is very confusing, and no one in the New Model Army is sure what to do now that they hold all the cards. So the New Model Army decides to have a public debate at Putney in late October in order to hash out what the Army's position is going to be.

At Putney, both sides put forward manifestos for what the Army should stand for. The Agitators put forward the "Agreement of the People," which calls for:

the Long Parliament to be dissolved and elections to be held for a new Parliament.

these elections to be held after a reapportionment of Parliament to establish equal districts on the basis of one-man-one-vote.

elections for a new Parliament every two years.

the electorate to be made up of "all men of the age of one and twenty years and upwards (not being servants, or receiving alms, or having served in the late King in Arms or voluntary Contributions)." (i.e, fairly universal male suffrage).

Parliament is to have full Executive and Legislative authority, except that the people shall have liberty of conscience, freedom from conscription, equality before the law, and there shall be amnesty for anything done or said during the Civil War.

The Grandees, who freaked the fuck out when they heard these terms and started immediately calling the Agitators "Levellers" (i.e, 17th century for "commie bastards"), put forward the "Heads of Proposals," which calls for:

the Long Parliament to be dissolved and elections to be held for a new Parliament.

these elections to be held after Parliament decides on "some rule of equality of proportion...to the respective rates they bear in the common charges and burdens of the kingdom," or on the basis of some other rule that will make the Commons "as near as may be" to equally proportioned.

for the next ten years, Parliament and not the King has authority over the military, finances, and the bureaucracy.

for the next five years, Royalists aren't allowed to run for elected office or hold appointed public offices.

the Church of England will continue to exist, but you don't have to read the Book of Common Prayer if you don't want to, you don't get fined for not going to CoE services or attending other services, and there will be no imposition of a Presbyterian Covenant.

You can see that there are some overlapping areas (no more Long Parliament, elections every two years, some form of reapportionment, some form of liberty of conscience) but there are some really significant differences - a republic versus a constitutional monarchy, a unicameral Parliament versus retaining the House of Lords, and universal suffrage versus property requirements.

During the Putney Debates, Cromwell flatly refuses to accept anything other than a constitutional monarchy, Ireton (Cromwell's son-in-law) refuses to accept universal suffrage, but the two sides agree that a committee will work out a compromise on the basis of everything else from the "Agreement" as long as the Agitators agree to go back to their regiments.

Then the King escapes from captivity and everyone panics. Cromwell and Fairfax scramble a new manifesto together and try to get the New Model Army to approve that manifesto along with everyone taking a loyalty oath to Fairfax and the General Council of the Army, the Agitators see this as a stab in the back and start up a mutiny, and Cromwell and Fairfax crush the mutiny and arrest the Agitator leadership. In late November 1647, Charles I, who has been recaptured by this point, signs a secret agreement with the Scots to invade England and restore Charles to the throne in return for Presbyterianism being established in England.

The Second Civil War

Things slow down for a bit, because the Scots are actually quite divided about this agreement - the Kirk actually condemns it as "sinful" - and it takes until April for the pro-agreement faction (known as the "Engagers") to get a majority in the Scottish Parliament.

In May 1648, Royalist uprisings break out across the kingdom, with South Wales, Kent, Essex, and Cumberland being particular centers of Royalist strength, and the Scottish Covenanter army crosses the border and invades England. Unfortunately for Charles, the Royalists, the English Presbyterians, and the Scots, they completely fail to coordinate their actions and the New Model Army is able to completely crush the uprisings one-by-one and then turns its attention to the Scots.

At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, the New Model Army under Cromwell wins another one of its ridiculously lopsided victories that make his emerging belief that he had been chosen by God somewhat understanable, and the formidable Covenanter army is crushed.

By this point, Cromwell and the rest of the Grandees are convinced of two things: one, no more negotiating with the King. As the Army Council put it rather ominously, it was their duty "to call Charles Stuart, that man of blood, to an account for that blood he had shed, and mischief he had done." Two, the (English) Presbyterians could not be trusted. They had conspired with the King and their Scottish co-religionists to overthrow the government and abolish religious liberty, and thus they had to go.

Thus, in December 1648, Pride's Purge is carried out, in which a detachment of troops acting under orders from Ireton (and thus from Cromwell) bar 140 MPs from taking their seat and arrest 45 of them. This effectively ends the Long Parliament, and the remaining 156 MPs continue to sit as the Rump Parliament. In the New Year, the Rump Parliament then votes to put the King on trial for treason and then afterwards establishes the Commonwealth as a unicameral Republic.

What Comes Next?

You'll note a couple things at this point: first, Cromwell's political positions are fairly fluid and change with events, so that he goes from being a staunch constitutional monarchist in late 1647 to a determined regicide by January 1649. Second, even though it's been a few years since the Putney Debates, Cromwell and the Grandees haven't implemented the "Heads of Proposals" - most crucially, they haven't dissolved Parliament and called for new elections, nor has a new Constitution been established.

Initially, one might say that Cromwell was distracted by his campaign to crush the Confederate-Royalist coalition in Ireland and then to crush the alliance between the Covenanters and Charles II. But by 1651, he's back in England and there's still no election and still no Constitution. Cromwell tries to get the Rump Parliament to call for new elections, establish a new Constitution that incorporates Ireland and Scotland now that they've been conquered, and finds some sort of religious settlement.

For two years, the Rump Parliament deadlocks on practically everything except the religious settlement, where it manages to piss off everyone by keeping the Church of England and its tithes, but also getting rid of the Act of Uniformity and allowing Independents to worship openly, but also passing all kinds of Puritan moral regulations. In April of 1653, Cromwell proposes that the Rump Parliament establish a caretaker government that will deal with the Constitution and new elections, but the Rump deadlocks on that too. This causes Cromwell to completely lose it and dissolve the Rump Parliament by force, culminating in one hell of a speech:

It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place, which you have dishonoured by your contempt of all virtue, and defiled by your practice of every vice; ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government; ye are a pack of mercenary wretches, and would like Esau sell your country for a mess of pottage, and like Judas betray your God for a few pieces of money.

Is there a single virtue now remaining amongst you? Is there one vice you do not possess? Ye have no more religion than my horse; gold is your God; which of you have not barter'd your conscience for bribes? Is there a man amongst you that has the least care for the good of the Commonwealth?

Ye sordid prostitutes have you not defil'd this sacred place, and turn'd the Lord's temple into a den of thieves, by your immoral principles and wicked practices? Ye are grown intolerably odious to the whole nation; you were deputed here by the people to get grievances redress'd, are yourselves gone! So! Take away that shining bauble there, and lock up the doors. In the name of God, go!

Now there's no more Parliament and Cromwell and the Council are running the country on their own, but they don't have a plan for what to do next. A Fifth Monarchist member of the Council proposes appointing a "sanhedrin of saints" on the basis of religious credentials who will set up a godly commonwealth and bring about the imminent return of Christ. That doesn't happen, but the Council does like the idea of an appointed (rather than elected) body called the Nominated Assembly, which becomes known as Barebone's Parliament. This Parliament doesn't make it a year because of how badly it's divided between moderate republicans who want a functioning government and Fifth Monarchists who believe that Jesus Christ is coming back to Earth any day now, so why bother? Ultimately, Barebone's Parliament dissolves itself.

This then leads the Council to pass the Instruments of Government, which was essentially an adapted version of the original "Heads of Proposals." Under the Instrument, Executive power would be held by the Lord Protector who would serve for life, Legislative power would be held by a Parliament elected every three years, and then there would be a Council of State appointed by Parliament which would advise and elect the Lord Protector upon the death of the previous occupant. Thus, the Protectorate is born.

In 1654, Cromwell finally manages to get the First Protectorate Parliament elected...and it only lasts a single term, agrees to none of the 84 bills that Cromwell and the Council of State, and is promptly dissolved as soon as the Instruments would allow. And so on it went through the Second and Third Protectorate Parliaments, and then Cromwell died and the rest is history.

Conclusion

Coming back to what I mentioned at the very beginning about the interplay between structural factors and individual actions, I think we can see a kind of ratchet effect whereby decisions taken early on that foreclosed certain options compound on each other over time, leading to structural factors that weakened the Commonwealth.

The crucial turning point(s) to me are the decision to reject the Agreement of the People in 1647 and then the failure to enact the Heads of Proposals in 1647 after the Putney debates, or in 1648 or 1649 after Pride's Purge.

With the Agreement, you could have had a small-d democratic republic which would have offered ordinary working people new political rights and protections and the opportunity to buy-in to the new regime through an election for a new Parliament. With the Heads of Proposals, you could have had a more conservative republic that would have offered much the same to the traditional landed political class, which would have then granted their consent to the new regime by both standing for election and voting in that election for a new Parliament.

That kind of legitimacy was absolutely necessary in order to ensure the long-term allegiance of the population to the new regime in the face of Royalist revanchism, let alone the kind of radical changes (putting the king on trial, declaring a republic, establishing a religious settlement) that Cromwell and the Grandees saw as essential.

#history#english history#oliver cromwell#english commonwealth#english civil war#wars of three kingdoms#early modern history

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

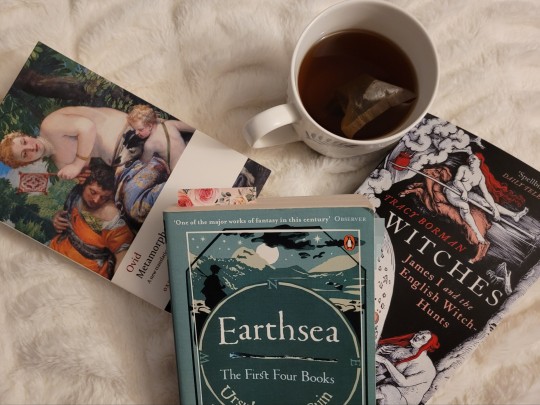

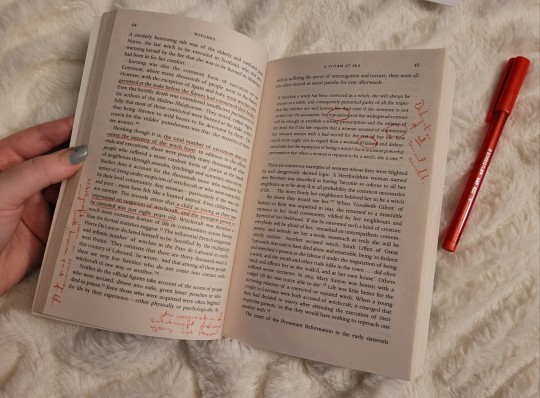

A slow bank holiday Monday evening - I'm slowly having my faith in popular history restored with Boreman's book on 17th century witch-hunts and finally tackling Ovid in full. Plus I'm returning to Earthsea with The Farthest Shore!

#studyblr#gradblr#books#reading#early modern history#witches: james i and the English witch-hunts#tracy borman#the farthest shore#ursula k. le guin#ovid#metamorphoses

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Buccleuch Collection miniature of Catherine of Aragon

#catherine of aragon#katherine of aragon#catalina de aragon#tudor history#henry viii#the tudors#english history#tudor era#tudor england#tudor period#tudor dynasty#house of tudor#16th century#16th century art#sixteenth century#reniassance#renaissance art#early modern#art#art history

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nell Gwyn, mistress of Charles II, in virginial white handling some sausages.

Charles II was known for his saucy mistresses and the way he paraded them throughout court. His sex life was no secret, and sharp contrast to the Puritan values of the previous decades in England. This portrait, amongst others, is an example of how Charles treated his mistresses as important figures in the court, and Stuart court attitudes towards sex.

#nell gwyn#charles ii#charles ii of england#early modern#history#early modern england#english history#art history#stuarts#stuart england

105 notes

·

View notes