#kropotkin

Text

#196#r/196#gardening#communism#kraz mazov#karl marx#kropotkin#conquest of tomatoes#conquest of bread#socialism#anarchism#anarcho-goblinism#anarcho-imgonnaeatyourfuckingvegetablesism#YUM!

834 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, been wanting to read Kropotkin for a while but I dont know where to begin, any suggestion/recommendation? Anarchist Morality and Mutual Aid seem to be the most popular...

I always really liked An Appeal To The Young as a starting pont, because its just a bunch of texts addressing young students and workers, basically asking them what they want from life and telling them to think about why they should start dedicating their whole lives to the accumulation of capital and personal gain.

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“To remain the servant of the written law is to place yourself every day in opposition to the law of conscience, and to make a bargain on the wrong side”

- Peter Kropotkin

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

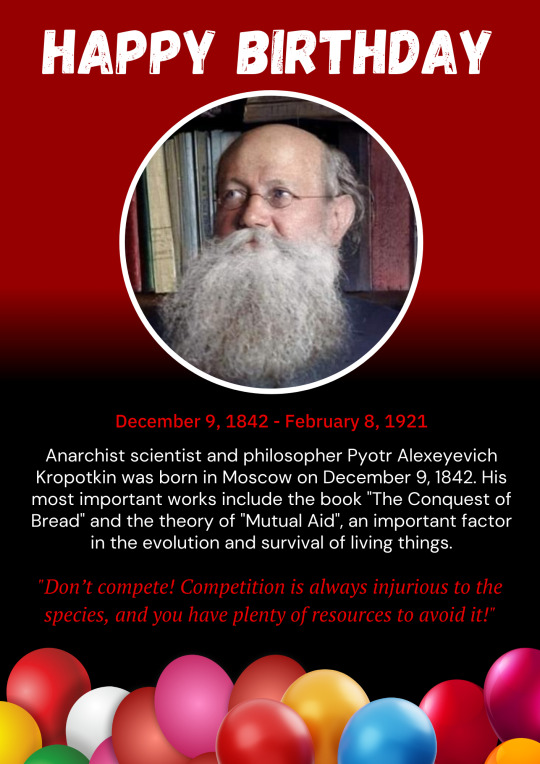

Today is the birthday of Anarcho-communist scientist and philosopher Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unrueh, dir. Cyril Schäublin (Switzerland 2022)

#unrueh#unrest#désordres#cyril schäublin#film#cinema#movies#Switzerland#2022#clockwork#anarchism#kropotkin#capitalism#time

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was talking to a fellow Stirner-enthusiast once and he asked who else I was influenced by. I mentioned Kropotkin and he said he was never able to get past Kropotkin's "idea that the medieval burgs were anarchist." This was not actually an idea Kropotkin had.

Kropotkin never claimed the medieval burgs were anarchist. He just wrote that they had a relatively high degree of decentralization and self-government compared to the modern nation-state.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

santa claus

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

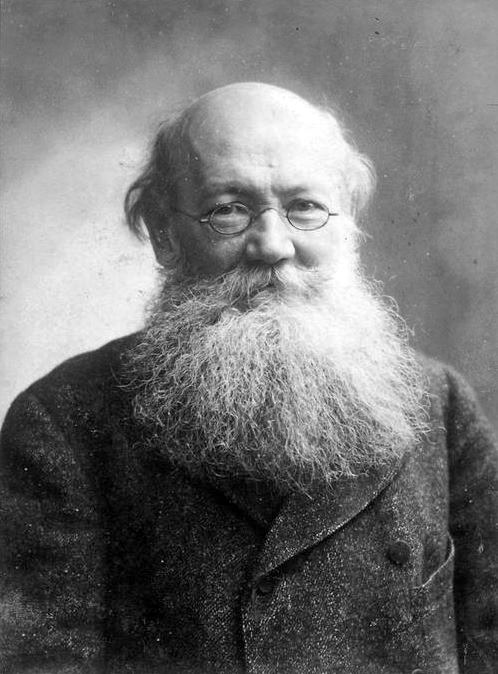

[Video] Rare footage of anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin in 1917 at the age of 74

Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin, (born December 9, 1842, Moscow, Russia—died February 8, 1921, Dmitrov, near Moscow), Russian revolutionary and geographer, the foremost theorist of the anarchist movement. Although he achieved renown in a number of different fields, ranging from geography and zoology to sociology and history, he was eternalized for the life of a revolutionist.

Early life and conversion to anarchism

The son of Prince Aleksey Petrovich Kropotkin, Peter Kropotkin was educated in the exclusive Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg. For a year he served as an aide to Tsar Alexander II and, from 1862 to 1867, as an army officer in Siberia, where, apart from his military duties, he studied animal life and engaged in geographic exploration.

Kropotkin’s findings won him immediate recognition and opened the way to a distinguished scientific career. But in 1871 he refused the secretaryship of the Russian Geographical Society and, renouncing his aristocratic heritage, dedicated his life to the cause of social justice. During his Siberian service he already had begun his conversion to anarchism—the doctrine that all forms of government should be abolished—and in 1872 a visit to the Swiss watchmakers of the Jura Mountains, whose voluntary associations of mutual support won his admiration, reinforced his beliefs. On his return to Russia he joined a revolutionary group, the Chaiykovsky Circle, that disseminated propaganda among the workers and peasants of St. Petersburg and Moscow. At this time he wrote “Must We Occupy Ourselves with an Examination of the Ideal of a Future System?,” an anarchist analysis of a postrevolutionary order in which decentralized cooperative organizations would take over the functions normally performed by governments.

He was imprisoned in 1874 for his ideas but was freed by his comrades in a sensational escape 2 years later, fleeing to western Europe, where his name soon became revered in radical circles. The next few years were spent mostly in Switzerland until he was expelled at the demand of the Russian government after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by revolutionaries in 1881. He moved to France but was arrested and imprisoned for 3 years on trumped-up charges of sedition. Released in 1886, he settled in England, where he remained until the Russian Revolution of 1917 allowed him to return to his native country.

Philosopher of revolution

Kropotkin’s aim, as he often remarked, was to provide anarchism with a scientific basis. In Mutual Aid, which is widely regarded as his masterpiece, he argued that, despite the Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest, cooperation rather than conflict is the chief factor in the evolution of species. Providing abundant examples, he showed that sociability is a dominant feature at every level of the animal world. Among humans, too, he found that mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. He traced the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations—trade unions, learned societies, the Red Cross—that have continued to practice mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. The trend of modern history, he believed, was pointing back toward decentralized, nonpolitical, cooperative societies in which people could develop their creative faculties without interference from rulers, clerics, or soldiers.

In his theory of “anarchist communism,” according to which private property and unequal incomes would be replaced by the free distribution of goods and services, Kropotkin took a major step in the development of anarchist economic thought. Kropotkin envisioned a society in which people would do both manual and mental work, both in industry and in agriculture. Members of each cooperative community would work from their 20s to their 40s, four or five hours a day sufficing for a comfortable life, and the division of labour would yield a variety of pleasant jobs, resulting in the sort of integrated, organic existence.

To prepare people for this happier life, Kropotkin pinned his hopes on the education of the young. To achieve an integrated society, he called for education that would cultivate both mental and manual skills. Due emphasis was to be placed on the humanities and on mathematics and science, but, instead of being taught from books alone, children were to receive an active outdoor education and to learn by doing and observing firsthand, a recommendation that has been widely endorsed by modern educational theorists. Drawing on his own experience of prison life, Kropotkin also advocated a thorough modification of the penal system. Prisons, he said, were “schools of crime” that, far from reforming the offender, subjected him to brutalizing punishments and hardened him in his criminal ways. In the future anarchist world, antisocial behaviour would be dealt with not by laws and prisons but by human understanding and the moral pressure of the community.

Kropotkin combined the qualities of a scientist and moralist with those of a revolutionary organizer and propagandist. For all his mild benevolence, he condoned the use of violence in the struggle for freedom and equality, and, during his early years as an anarchist militant, he was among the most vigorous supporters of “propaganda by the deed”—acts of insurrection that would supplement oral and written propaganda and help to awaken the rebellious instincts of the people. He was the principal founder of both the English and Russian anarchist movements and exerted a strong influence on the movements in France, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Return to Russia of Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin

Events took an unexpected turn with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Kropotkin, by this time age 74, hastened to return to his homeland. When he arrived in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in June 1917 after 40 years in exile, he was greeted warmly and offered the ministry of education in the provisional government, a post he brusquely declined. Yet his hopes for the future were never brighter, because in 1917 the organizations that he thought might form the basis of a stateless society—the communes and soviets, or soldiers’ and workers’ councils—suddenly began to appear in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

With the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, however, his earlier enthusiasm turned to bitter disappointment. “This buries the revolution,” he remarked to a friend. The Bolsheviks, he said, have shown how the revolution was not to be made—that is, by authoritarian rather than libertarian methods. Kropotkin’s last years were devoted chiefly to writing a history of ethics, one volume of which was completed. He also fostered an anarchist cooperative in the village of Dmitrov, north of Moscow, where he died in 1921. His funeral, attended by tens of thousands of admirers, was the last occasion in the Soviet era when the black flag of anarchism was paraded through the Russian capital.

Kropotkin’s life exemplified the high ethical standard and the combination of thought and action that he preached throughout his writings. He displayed none of the egotism, duplicity, or lust for power that marred the image of so many other revolutionaries. Because of this he was admired not only by his own comrades but by many for whom the label of anarchist meant little more than the dagger and the bomb. The French writer Romain Rolland said that Kropotkin lived what Leo Tolstoy only advocated, and Oscar Wilde called him one of the two really happy men he had known.

#κροπότκιν#kropotkin#piotr kropotkin#peter kropotkin#russia#russian#anarchist#anarchism#anarchy#newsreel#old#old film#old movie#black and white#Youtube

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

My political philosophy in one image

#arknights#reed#kropotkin#if Reed is an anarchist does that make Eblana a tankie#please don't think too hard about that

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Love to see Marxists still arguing about measuring or not measuring value when a non-marxist like Kropotkin already came up with the better position way back in 1892:

You can't measure it and shouldn't want to even if you could. Expropriate everything now and base life on need."

#marxist leninist#marxist theory#marxism#marxist feminism#marxist#peter kropotkin#kropotkin#lol#lmao#lulz#hehe haha#haha funny#haha lol#haha#life#needs#wants#endure and survive#survive#politics#neoliberal capitalism#capitalist dystopia#capitalist bullshit#capitalist hell#capitalism#ausgov#auspol#tasgov#taspol#politas

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin no eran "amoralistas" como algunos de los rumiadores sosos de Nietszche en Alemania que se titulan anarquistas y son bastante modestos con considerarse "super-hombres". No han construido con habilidad una llamada "moral señorial y esclava" de la que toda clase de conclusiones se pueden sacar, pero al contrario se preocuparon de investigar el origen de los sentimientos morales en el hombre y lo hallaron en la convivencia social. Estando lejos de dar a la moral un significado religioso y metafísico, vieron en los sentimientos morales del hombre la expresión natural de su existencia social que se cristalizó lentamente en determinadas conductas y costumbres y servía de pedestal para todas las formas de organización que salían del pueblo.»

Rudolf Rocker: Anarquismo y organización. Ideas, pág. 6. Barcelona, 1982.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#rudolf rocker#proudhon#bakunin#kropotkin#nietzsche#anarquismo#moral#moral señorial y esclava#moral de los señores#moral de los amos#moral de los esclavos#amoralismo#amoralistas#sentimiento moral#conducta#costumbre#organización#super-hombre#superhombre#pueblo#existencia social#formas de organización#amoral#amoralidad#anarquismo y organización#anarquismo individualista#teo gómez otero

10 notes

·

View notes

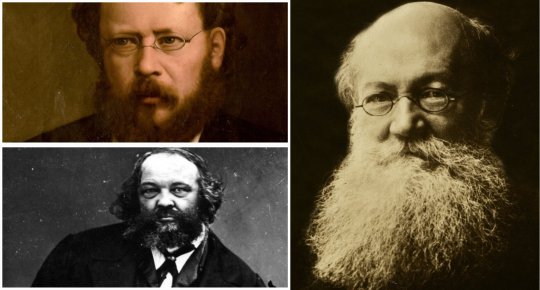

Photo

“The Anarchist formerly known as Prince”

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Conquest of Insulin

Someone said, on a post I reblogged recently, that we need a good anarchist answer to the tumblr question du jour about insulin and how it would be produced “under anarchism”.

I suggest the answer has already been written, and that if you read Kropotkin’s “The conquest of bread” (yes, it’s all I’m banging on about at the moment) you can in fact apply the chapter on food to any essential of modern life that requires processing and is an immediate need.

Kropotkin was obviously writing at time when medicine was much less advanced than it is now, and I think it is necessary for modern anarchists to address the question directly. It does not apply just to insulin, but to many lifesaving drugs which are needed by people in the long term, as well as more short term medication, such as antibiotics, as well as preventatives such as vaccines. These are things that are essential in the modern world, and we should not accept that the revolution should not provide them, just as, as Kropotkin contends, the first concern of the revolution must be providing bread.

We cannot sit in our “talking shops” and discuss the provision of medication whilst people die- to do so would be to doom the revolution to failure, just as the French revolutions that Kropotkin references were doomed due to their inability to provision the people with food.

Yet we must also acknowledge that right now, even in “rich” or “civilized” western countries, there are people languishing due to lack of medical care, lack of access to drugs, indeed, including insulin. At the moment, the American government is engaged in the question of whether to cap the price of insulin at $35 a month-at the moment, people have to pay up to $300 a vial, and die for want of insulin. Which is, perhaps, why it is an issue present at the forefront of people’s minds, right now.

Anyway, what is the solution to providing insulin and other drugs during and after the revolution?

Kropotkin’s plan for bread and food is relatively simple, and I believe without much difficulty it could be reapplied to medicine.

Assuming the revolution takes place in a western country, there will be an existing supply of insulin (or whichever drug) in that country. All the drugs, held in pharmacies and hospitals, would need to be carefully catalogued and identified, and held in common by the revolutionaries. This, I believe, would not be difficult to do- just as Kropotkin says that committees of workers can do this for food, then I think committees of workers, ideally with the aid of a pharmacist, could do this for medicine.

For clarity, we are not talking about seizing medicine held in private homes, just that held by pharmacies and hospitals. (This is perhaps more relevant to the bit where Kropotkin talks about coats, and how he does not want to seize people’s coats, though this may be attractive to the shivering).

Then, the medicine that exists can be distributed according to need (rather than according to who has the ability to pay).

This would deal with short term need in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, and would hopefully provide an adequate level of medicine for all. Would it provide perfect medical care for everyone? Perhaps not, but neither does any extant system under capitalism, and it would at least be fair- because it would be done by the people, for the people and done according to need, not wealth.

So, what then? How do we obtain, or make, more of each medicine?

The process of making a known medicine is, in general, not that difficult. One needs the correct equipment, and the right “ingredients” but it’s a process that a lot of people can complete with relevant training. Many people will work in this industry without being degree educated, or having a high level of scientific knowledge- these people are by every definition “workers” and the hope of the revolution is that they would happily share this expertise with the rest of us, and we could all take a share in this sort of useful work.

If that seems naïve to you, then I think further work is required on your part to understand what is meant by “anarchism” and “worker” and “revolution” and that’s outside the scope of this essay.

A lot of the posts I see about this seem to assume all the infrastructure would be destroyed in the revolution- but that’s not the aim of the revolution. Equipment might be damaged, but workers have the skills to mend it, or assemble a similar process in an equally equipped lab.

The aim of the revolution is not to destroy every laboratory or factory in the country or the world. If this happens, one might argue that the revolution has already failed. The aim of the revolution is to take over the means of production and use them for the good of everyone. I think many people are trying to argue about the production of insulin (or other drugs) in the post apocalypse, and this is not the same as post revolution. It is very important to understand that! However, personally, I would rather live in an anarcho-communist society post apocalypse, than in a individualistic one clinging to the old ways of capitalism- but again, that is outside the scope of this essay.

Therefore, we, relatively quickly, post revolution, are likely to have the means available to make many common medications and provide them to the people in need of them. I will talk, shortly, about how one obtains the raw materials needed for this, but let us assume that some quantity of the raw materials will be available in the places where these things are made.

I want to talk a little bit about work now, because yes, making these things will require a level of work. People already do that work, and are, of course, paid for it. I believe many young people who look to anarchism look for a world without work- but that cannot exist- even in the “fully automated luxury space communism” of our memes, work would be needed of some kind.

The point is that the work would be significantly lessened and done for the good of all. The worker would be assured of good housing where they did not have to worry about turning on the heating, or using energy, with a supply of varied and interesting food, and all the basic things necessary for their wellbeing (think how many workers currently rent insecure and inadequate housing, think about the stories about nurses using foodbanks- this is no small gift).

Moreover, there would be many people engaged in what we might consider “useless work” in fields such as property or finance or “government” or indeed the provision of services to the wealthy, who would now have no work to do. These people, many of whom are not wealthy, may be willing to spend an hour of their day, or a day of their week doing work that is useful and beneficial to someone, given that all their basic needs are provided for. And so, the lab worker, who was working for five days a week, for eight hours a day, now only needs to work for three days a week, then perhaps two, or only half days- and therefore their life is further improved.

I am not talking about forced labour here, but I do believe that people would do it- because it is necessary, and it would not be hard. We can’t pretend that difficult jobs (and I think there are far more difficult or unpleasant jobs) would go away under anarchism. But I think if people knew they would have a good standard of living, and only needed to work for, say, 10 hours a week, they would do it. People would do it for the good of the community, because people are fundamentally good, and care about each other- “anarchy is for lovers” as it were. And again, if you don’t believe this, then there are far more fundamental problems in your understanding of anarchism, and they are outside the scope of this essay.

So, we have dealt with the immediate provision of insulin and other medicines, and we have dealt with the question of work. However, there is, perhaps, a more difficult question about obtaining raw materials. Many medicines, and their packaging, which keeps them safe for use, are complex and require complex ingredients which need to be obtained, and may well need to be obtained from outside the country or the area where the revolution has occurred.

Again, we return to Kropotkin and his bread. Kropotkin imagines a revolution occurring at first in one city (Paris, because the Paris commune is his model). Paris has no means of immediately producing more bread, and in this model, the countryside is not yet part of the revolution. But Kropotkin proposes that the city can produce things that are useful to the peasant farmers of the countryside and trade with them for bread, or the ingredients of bread, essentially by barter, offering them things they previously could not afford. (This, in turn, helps liberate the farmers).

So, this is difficult in a globalized society, where ingredients may come from other countries, and the movement and supply is run by large companies.

Firstly, the job is to find out what ingredients are needed. There are people (many) who know this, and companies keep records.

Secondly, you’d see which materials you can produce yourselves, or recycle. In the case of insulin specifically, it’s actually produced by gene editing certain bacteria and harvesting the products. As long as you keep the extant bacterial colonies alive, the raw materials needed for production are relatively minimal, and the packaging is something that is relatively easy to produce. I think there are drugs where obtaining them would actually be far more complex than insulin.

That’s obviously a very short step for a very difficult process, but with the relevant scientists (and there are a lot of them) given all the resources and help possible (which is not what they get under the current system) I do believe that many creative solutions could be found. And there would be a high level of help available, including from many, many people employed in the pharmaceutical industry in previously redundant roles such as “sales” and “marketing”- who still, often, have relevant scientific qualifications.

So, what about the things we can’t produce or recycle? Things we may need to obtain from an area outside of the revolution? It’s true, here, things become difficult, and of course we have to consider the issues of other powers imposing “sanctions” on the area of the revolution, as happens to countries such as Cuba, and Venezuela, and so on.

I do think Kropotkin’s proposition of direct barter with workers has merit. It is more logistically difficult when larger distances are involved, of course, but it’s something to be attempted, and has the added bonus of undermining capitalism in the areas of the world where it still exists.

I think we know, unfortunately, without the optimism of the early 20th Century, that revolution is slow to spread, and will be resisted in the strongest possible terms by capitalist powers. Therefore, for those of us who live in Capitalist countries, I think there is a very strong duty to aid any country where revolution is taking place or has recently taken place and to resist any efforts of our own country to impose sanctions, etc.

That said, those of us in “western” or wealthy countries have got used to depending on the resources of poorer countries- despite the fact that the empires of Europe are (largely) a thing of the past, countries still rely on system that is not so different to the colonial era. Some countries supply things to make other countries wealthier, whilst their own people suffer in poverty. This situation cannot be allowed to continue, and that is a problem that decentralized anarchist communities would have to grapple with. However, it may be, nonetheless possible for these communities to assist those in poorer communities and be repaid through a system of barter.

I do believe by the means I’ve described so far, most medication, and indeed most things considered essentials to wellbeing in modern life could be provided after the revolution, and in a better, fairer way than after capitalism.

However, perhaps we should talk about shortages. It’s true, shortages may exist. Capitalism is no protection against shortages- however, under capitalism, there is a mechanism of distribution during periods of shortage. Those that can pay the most get the item. When there is a shortage, prices rise, the rich pay, and the poor do without (or die).

Under an anarchist system, or an anarcho-communist one, at least, resources will be allocated according to need. Those who need the thing the most will get it. If there are lots of people in need, and not enough to go around, then a system of rationing may need to be implemented. Is this perfect? No. But is it fairer? Yes.

And during that rationing of that thing, people will at least be provided with the other things that can be provided- that is to say they won’t be selling all they own, or taking on excessive debt in order to try and get the thing. And they will know that people, very many people, are working together to try and get them the thing which they need.

I don’t believe it’s reasonable to hold any system set up in opposition to capitalism to the standard of perfection, certainly not in the immediate aftermath of revolution. The standard should be “significant improvement on capitalism for the majority of people” perhaps- and I believe fair provision of medicines without cost to the person who needs it is much fairer than current systems which exist in many so called “developed” countries, where people still die directly of poverty related causes, whilst the rich have so much surplus.

Taking the specific example of insulin to, perhaps, a worse case scenario, it is possible to obtain usable insulin from the pancreases of cows and pigs. Obviously this is very, very far from ideal, and would only need to be used in extremis, due to short term problems with production, but as an option it does exist. In examples that assume widespread destruction, this seems the most practical way of getting insulin to tide people over in the short term, whilst we rebuild. But as I say, such widespread destruction is not the aim of revolution, nor necessary to remove capitalism.

But the point is that for insulin, and most modern medicines that exist, the work of making them is not so different to working in a factory. There are lots of people who do it, lots of people who know how to do it, instructions held by companies on how to do it, facilities to do it or that can be adapted to it, and so doing it post revolution is not such a difficult problem.

The difficult work, for insulin, has already been done- that work is a) identifying the problem that causes the illness, b) finding a cure and c) finding a way to mass produce that cure.

On January 23rd, 1923 Banting, Best, and Collip were awarded the American patents for insulin. They sold the patent to the University of Toronto for $1 each. Banting said: “Insulin does not belong to me, it belongs to the world.” His desire was for everyone who needed access to it to have it.

Under capitalism, one will note that desire has not been met.

But this is not some esoteric knowledge known only to a few. It’s knowledge that is widely held, understood and accessible, and that post revolution can be taught to even more people. In the shortest term, immediately after the revolution, it’s possible that there may be some problems with the supply of some goods, and yes, that may include insulin. It’s most likely, that in the medium to longer term post revolution, the production of insulin would increase, and it would be more accessible, not less- because it wouldn’t be limited by patents, by private companies, there wouldn’t be the desire for profit making. There would be work involved in its production, but the work would be shared fairly, the workers would live in comparative security compared to today, and the products of that work would be shared fairly, according to need.

#anarchism#anarchocommunism#insulin#anarchy#anarchy essay#long post#kropotkin#inspired by kropotkin#politics#essay

120 notes

·

View notes