#fitrat

Text

Emoto, su damlacıklarını dondurup fotoğraf çekme kapasitesi olan karanlık alan mikroskobu altında incelediğinde, insanın titreşimsel enerjisinin, düşüncesinin, kelimelerinin, fikir ve müziğin hatta suya oynatılan filmlerin dahi suyun moleküler yapısını etkilediği bilgisine varmıştır.

Su kristalleri deneyinin çok daha ilginç olan kısmı ise, sadece kâğıt parçalarının üzerlerine farklı anlamlardaki kelimeler yazılıp bunlar su şişelerine yapıştırıldıklarında dahi suyun etkileniyor olmasıdır. Yani su sadece söylenilen değil, düşünülen kelimelerden de etkilenmektedir.

Bu tezin su üzerindeki kanıta baktığımızda, üzerinde teşekkürler yazılı şişedeki suyun son derece güzel bir kristalle tepki verirken, aptal kelimesi yazılı şişedeki suyun biçimsiz, parçalı kristal şekilleriyle tepki verdiği gerçeği karşımıza çıkmaktadır.

Bu bağlamda çocuğumuza söylediğimiz kötü sözlerin onun ruhunda oluşturduğu olumsuz etkiler bir tarafa, zihnimizde kurguladığımız menfi etiketlerin bile çocuğa olumsuz tesir ettiği sonucuna varılabilmektedir.

Zira insanın da %65'i sudur. Nasıl ki su kötü sözlerden ve etiketlerden olumsuz etkileniyorsa, aynı şekilde hem dilimizdeki hem zihnimizdeki olumsuzluklar da çocuğumuzu menfi bir biçimde etkisi altına alacaktır.

Tembel denilen çocuk tembellik eğilimi gösterecek, aptal denen çocuk zihni potansiyelini tekâmül ettiremeyecektir. Hele ki hiperaktif, dikkatsiz gibi yalnızca hekimlerin teşhis edebileceği hastalık tanımlarını çocuğumuza yapıştırmak, ona yapılabilecek en kötü şeylerden biridir.

Suyun dönüştürücü etkisini olumlu yönde kullanmak yine anne-babalara verilmiş önemli bir nimettir. Nasıl ki olumsuz telkinler çocuğumuzu olumsuza yönlendiriyorsa, tam tersi noktada olumlu telkinler de onu olumluya taşıyan yolu açmış olacaktır.

#hatice Kübra tongar#fitrat#deney#kanıt#su#zihin#kristal#molekül#olumsuzluk#olumluluk#çocuk#çocuk eğitimi#book#kitap#kitaptavsiyesi#kitap tavsiyesi#kitap tavsiyeleri#kötü#söz#şişe

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Run, run, run... #outdoorworkout #workout #outdoor #fit #outdoorfitness #fitness #fitfam #fitrat #fitnessaddict #fitnesslife #fitspo #sport #sportwear #sportswear #gay #gayguy #gayfit #fitgay #czechgay #muscle #gym #gymfit #fitgym #gymtime #fitlife #fitover40 #healthylifestyle #inshape #cardio #sexy https://www.instagram.com/p/B-w1JbHJS5f/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#outdoorworkout#workout#outdoor#fit#outdoorfitness#fitness#fitfam#fitrat#fitnessaddict#fitnesslife#fitspo#sport#sportwear#sportswear#gay#gayguy#gayfit#fitgay#czechgay#muscle#gym#gymfit#fitgym#gymtime#fitlife#fitover40#healthylifestyle#inshape#cardio#sexy

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 35 Turkestan and Bolshevism 1918

For this episode, we’re going to leave the Alash Orda in the Steppe with their Bolshevik and White Movement problem and return to the Jadids in Turkestan. Things were not going well for the Jadids. The Tashkent Soviet strangled the Kokand Government before it could breathe, the Bukharan and Khivan Emirs showed no interest in reform. Famine swept the land and the Basmachi were organizing themselves in the Ferghana. The Jadids themselves were on the run, without any real power, and the Bolsheviks were determined to spread communism into the region.

Enter Pyotr Kobozev

Lenin understood that the first step in regaining control over Turkestan was to settle the dispute between the indigenous peoples and the settlers. While the Bolsheviks negotiated with the Alash Orda in the Kazakh Steppes and the Czech Legion made their way to Vladivostok, the Bolsheviks appointed Pyotr Kobozev as plenipotentiary commissar for Turkestan.

Pyotr Kobozev

[Image Description: A black and white drawing of a man in a military cap with a star and the sickle and hammer. He has a thick, circular beard and mustache. He is looking to the left. He is wearing a white shirt and dark coat.]

Kobozev is an interesting figure of the Russian Civil War. He was born on August 4th, 1878, in the village of Pesochyna, Russia. He was born to a Moscow railroad employee but fell in love with theology and attended the Moscow seminary. He either left (or was expelled for taking part in a student uprising) and attended the Moscow secondary school of Ivan Findler. He frequented Marxist circles and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1898 while attending the Moscow Higher Technical School before being expelled once more for taking part in a student strike. He was exiled to Riga, Latvia. He remained involved with Marxist and Communist circles, making it almost impossible to find work. In 1915 he moved to Orenberg where he worked a railroad engineer and the leader of the city’s Russian Social Democratic Labour Party.

During the February Revolution he organized an agitation train along the Orenburg-Tashkent route, urging for support of the Bolsheviks. He would have been the Commissar of the Tashkent Railroad if the Provisional Government had not blocked his appointment. Instead, he was appointed the chief inspector over the educational institutions of the Ministry of Transport. Then the October Revolution.

Ataman Alexander Dutov took advantage of the revolution to claim power in the Orenburg region, which the Bolsheviks opposed. Kobozev was appointed the extraordinary commissar for the resistance to Dutov’s counterrevolution. He spent the rest of 1917 planning an assault on Dutov’s forces, reclaiming the city in January 1918. It is said he drove one of the armored trains himself.

After he reclaimed Orenburg, Kobozev was sent to Baku to nationalize the local old industry. With 200 million rubles, he was able to prop up the Bolsheviks in Orenburg, Baku, and Tashkent, successfully re-establishing the oil flow to Russia. In early 1918, Lenin sent a telegram to the Tashkent Soviets, announcing the arrival of Kobozev and two members of the People’s Commissariat of Nationalities in Tashkent. One of his travel companions was Arif Klebleyev a former member of the Kokand Autonomy. In fact, he was the one who sent a telegram to the Tashkent Soviet asking they recognize the Kokand Autonomy as a legal authority in Turkestan. Now he was working with the Soviets.

Lenin’s telegram read:

“We are sending to you in Turkestan two comrades, members of the Tatar-Bashkir Committee at the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities Affairs, Ibrahimov and Klebleyev. The latter is maybe already known to you as a former supporter of the autonomous group. His appointment to this new post might startle you; I ask you nevertheless to let him work, forgiving his old sins. All of us her think that now, when Soviet power is getting stronger everywhere in Russia, we shouldn’t fear the shadows of the past of people who only yesterday were getting mixed up with our enemies: if these people are ready to recognize their mistakes, we should not push them away. Furthermore, we advise you to attract to [political] work [even] adherents of Kerensky from the natives if they are ready to serve Soviet power-the latter only gains from it, and there is nothing to be afraid of in the shadows of the past” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 94

Kobozev arrived in April 1918 and made the following changes:

First, he forced the inclusion of indigenous peoples in governing bodies, including the Fifth Congress of Soviets that convened in Tashkent on April 21st, 1918.

He also elected himself as chair of the presidium during the Congress.

During the same congress, he created the Central Executive Committee of Turkestan (TurTsIK) as the supreme authority in the region. He ensured that nine of its 36 members were Muslims.

Second, he proclaimed a general amnesty for everyone involved with the Kokand Government.

Third, he created the Communist Party in Turkestan (KPT) in June 1918. By 1920, it would consist of 57 thousand members.

Fourth, He forced a re-election to the Tashkent Soviet, winning a “brilliant victory of ours in the elections to Tashkent’s proletarian parliament has decisively crushed the hydra of reaction…White Muslim turbans have grown noticeably in the ranks of the Tashkent parliament, attaining a third of all seats” - Adeeb Khalid, making Uzbekistan, pg. 94

The Rise of the Jadids

Jadids were not enthused at first. Between the bloodbath that followed the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of the Kokand Autonomy, they had little reason to trust the Bolsheviks. Abdurauf Fitrat would write in 1917:

“Russia has seen disaster upon disaster since the [February] transformation and now a new calamity has raised its head, that of the Bolsheviks!” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 95

G’ozi Yunus, another Jadid, would write about the Tashkent Soviet:

“Muslims have not seen a kopek’s worth of good from the Freedom [i.e., the Revolution]. On the contrary, we are experiencing times worse than those of Nicholas” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 95

For a moment, they looked to the Ottoman Empire as a source of salvation and G’ozi Yunus even traveled to Istanbul to petition the Ministry of War. When the Ottoman Empire was defeated during the world war (and Russia leaked the secret treaty between Britain and France divvying up Ottoman land amongst themselves), the world lost the last independent Muslim empire and the Jadids were forced to turn internally and to their neighbors for support.

The Jadids used their new political power to, first, punish their old enemies the ulama. They used the KPT in old city Tashkent to take land from the ulama and on May 21st, 1918, the commissar of the old city shut down the Ulamo Jamiyati, their journal al-Izoh and took its property. For the next two years, the Bolsheviks would requisition lands once owned by the ulama on the behalf of the new-method schools started by the Jadids and their theatrical groups, empowering one set of indigenous peoples over another. The Jadids also targeted the ulama’s control over the waqf. A waqf is a religious donation of land or money that can be used to support the community. The ulama controlled what could be donated and how it was distributed amongst the community. The Jadids, by taking control, wanted to use the waqf founds to support causes they thought worthy and would help modernize society.

The ulama for their part either found refugee with the more conservative elements of the society, joined the Basmachi, or attempted to win Bolshevik support by proclaiming that socialism had roots in Islam and they were the truly anti-capitalist sect whereas the Jadids were westernized modernizers who would bring about capitalism to Turkestan.

The Muslims of Turkestan were granted the right to use firearms, and, despite Kobozev’s efforts, the old dynamics returned to the city. The newer settlements remained the stronghold of the Russian settlers while the Muslims’ power was confined to the old city. The Jadids recruited Ottoman POWs to serve as teachers where they created clubs and secret societies. Some of these clubs were nationalistic, others were social gatherings. From 1918-1920, the Ottoman POWs became a core facet of Turkestan society as the indigenous peoples tried to survive the tumultuous end of the decade.

Turar Risqulov

The opening of the political world attracted other activists who did not support the Jadid’s version of reform. The Jadids got their start in political activism via the arts and education. This new cadre of politicians entered politics through the radicalization of the famine and violence against Muslim peasants and nomads and spoke the language of Bolshevism and the revolution. Many of these new politicians were younger than the Jadids and had gone through the Russian-native schools, giving them the benefit of speaking fluent Russian (similar to the members of the Alash Orda). Few had ever taken part in the Islamic reform championed by the Jadids.

Turar Risqulov

[Image Description: A black and white pciture of a man standing at an angle. He is looking at the camera. He has bushy black hair and a short mustache. He is wearing round, wire frame glasses. His hands are in his dark grey suit pants. he is wearing a white button down shirt, a grey tie, and a dark grey vest and suit jacket. A flag is pinned to his suit lapel.]

One of these men, a fascinating person who is my newest obsession was Turar Risqulov (1894-1938) He was born in Semirech’e to a Kazakh family who was poor but had high status. He went to a Russo-native school and worked for a Russian lawyer and then went to the agriculture school in Pishpek. In October 1916 he went to the Tashkent normal school and then the Russian revolution happened. Up to this point he had no public life but in 1917 he returned to his hometown of Merke and founded the Union of Revolutionary Kazakh Youth. He returned to Tashkent in 1918 and was named Turkestan’s commissar for health.

In November 1918, Risqulov was reporting to the Turkestan Sovnarkom about the situation in Avilyo Ota uezd where 300,000 Kazakhs died from starvation, but the settlers levied an additional tax of 5 million rubles on the survivors. Risqulov called this what it was-colonial exploitation This inspired an ideology of communistic anticolonialism. In May 1920, Turar wrote:

“In Turkestan as in the entire colonial East, two dominant groups have existed and [continue to] exist in the social struggle: the oppressed, exploited colonial natives, and European capital.” Imperial powers sent “their best exploiters and functionaries” to the colonies, people who liked to think that “even a worker is a representative of a higher culture than the natives, a so-called “Kulturtrager.” - Adeeb Khalid, Central Asia, pg. 170

For Turar the communist revolution was synonym was anti-imperialist in all its forms. If the revolution could not throw off the shackles of imperialism, then it was a failed revolution. While we’ll talk more about his political career, his ideology raises an important question for us: what did communism actually mean to the indigenous people of Central Asia?

A revolutionary example for the Muslim World

The Jadids

For the Jadids, Bolshevism was a revolutionary force they could use to achieve modernization. Even though they adopted Bolshevik language, they could not map the Bolshevik obsession with class to their own society. Instead, they translated class warfare into anticolonialism, conflating Islam, nationalism, and revolution into a singular vision of anti-imperialism with their enemies including the ulama, the emirs, and the British (the conquerors of the Ottomans and the latest colonizer of Muslim lands). Fitrat even went as far as to write that India’s efforts to overthrow Britain’s rule was

“as great a duty as saving the pages of the Quran from being trampled by an animal…a worry as great as that of driving a pig out of a mosque.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 103

The Jadids wanted to create a Turkestan that was Muslim, nationalistic, and revolutionary, free of settler dominance and source of revolution for the Muslim world. They discovered that the Bolsheviks shared in their belief in women liberation, economic redistribution, and power of the people (or proletariat). Additionally, the Bolsheviks had the power to do what the Jadids could not: overthrow the settlers and the emirs just as they overthrew the Tsar and the aristocracy of Russia. In 1919, the First Congress of Muslim Communists passed the following resolution:

“To the revolutionary proletariat of the East, of Turkey, India, Persia, Afghanistan, Khiva, Bukhara, China, to all, to all, to all!

We the Muslim Communists of Turkestan, gathered together at our first regional conference in Tashkent, send you our fraternal greeting, we who are free to you who are oppressed. We wait impatiently for the time when you will follow our example and take control in your own hands, in the hands of local soviets of workers’ and peasants’ deputies. We hope soon to come shoulder to shoulder with you in your struggle with the yoke of world capitalism, manifested in the East in the form of the English suffocation of native peoples” – Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 106

The Jadid’s embrace of an anticolonial revolution coincided with Afghanistan defeating the British in 1919, the wave of Ottoman POWs now free to roam Turkestan as well as an influx of Indian activists via Afghanistan. The Afghan Khan, Amanullah, looked to the Soviets for support against a British return. For their part, the Bolsheviks helped established a modern army in Afghanistan and allowed Afghanistan to open a consulate in Tashkent (but their relationship would always be strained whether because the Bolsheviks feared Afghan intervention in favor of the Bukharan Emir or because Afghanistan made no secret its desire to expand its influence into the rest of Central Asia).

The Indian activists (as well as many Ottoman expats) traveled through Afghanistan and into Turkestan to meet with the Bolsheviks, who represented an anti-colonial revolution about to overtake the world. Sakirbeyzade Rahim, an Anatolian representative would write in 1920 that:

“Turkestan is the path to liberation of the East, [and] the Red Soviets are the way to our natural and human rights. From now on, Turkestan and Turan will live only under the Red Soviet banner” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 105

Yet, despite all of this revolution activity, these efforts never materialized into an organized revolution. Instead, many hopeful revolutionaries came together, talked, and started nascent organizations, but were never able to go further than that.

If the Jadids believed they were the leaders of a Muslim revolution, what did the Bolsheviks believe?

The Bolsheviks

Back in 1917, the Bolsheviks were very anticolonial and Muslim friendly, claiming:

"All you, whose mosques and shrines have been destroyed, whose faith and customs have been violated by the Tsars and oppressors of Russia! Henceforward your beliefs and customs, your national and cultural institutions, are declared free and inviolable! Build your national life freely and without hindrance.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 91

I don’t think this changed as they marched into 1918, but their understanding of what Turkestan needed conflicted with what the Jadids and Alash Orda were fighting for. The Bolsheviks thought in terms of class and industry and for them nationalism was the form class took in the colonies. So, while they initially supported nationalistic projects, they always intended for nationalism to be a steppingstone to true communism. But for the Jadids and Alash Orda, nationalism was the end goal. The Bolsheviks failed to win the Alash Orda’s trust and support and they were determined now to make the same mistake in Turkestan.

But what made Turkestan so important for the Bolsheviks? There is an ideological and an economic reason.

Ideologically, the Bolsheviks believed that converting Turkestan to communism would open the door for further communist expansion into the East. As Lenin argued in November 1919:

“It is no exaggeration to say that the establishment of proper relations with the peoples of Turkestan is now of immense, world-historic importance for the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic. For the whole of Asia and for all the colonies of the world, for thousands and millions of people, the attitude of the Soviet worker-peasant republic to the weak and hitherto oppressed peoples is of very practical significance.” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan pg. 92)

This was particularly appealing as communist expansion floundered in the West. Trotsky would argue that:

“The road [to revolution in] Paris and London [lay] via the towns of Afghanistan, the Punjab, and Bengal” - Adeeb Khalid, Central Asia, pg. 172

They legitimately believed that Communism would flounder if it didn’t get a foothold outside of Russia and so they turned to the peoples the Tsar once oppressed. As they made overtures to the Jadids (and the Alash Orda) Lenin stressed the importance of not upsetting the indigenous peoples and to put the Russian settlers in their place before they ruined everything.

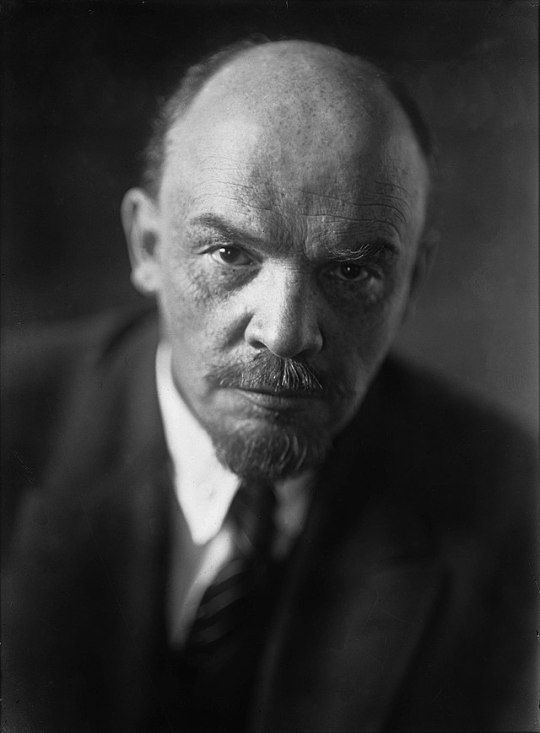

Vladimir Lenin

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a balding man staring intensely into the camera. He has a wiry mustache and goatee. He is wearing a white collared, button down shirt, a black tie, and a black suit]

Economically, the Soviets needed material and economic resources, especially cotton. The Russia the Soviet’s inherited was a stunted version of Tsarist Russia. No longer could they count on the economic and material resources of their western colonies and now the vast lands of the Steppe and Turkestan were at risk of escaping Russian control. The Commissar for Trade and Industry, L. B. Krasin, wrote:

“the recent reunion of Turkestan presents the opportunity…for making broad use of the region as well as of countries neighboring it…for the export of cotton, rice, dry fruits, and other goods necessary not only for the internal market of Russia, but also for its external trade.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 93

The challenge was benefiting from Turkestan’s resources without invoking the greed and bad memories of the Tsars.

By the end of 1918, the Jadids and Bolsheviks were working together to rebuild a functioning government in Turkestan. And yet, they both had two very different, clashing visions for Turkestan’s future. The Jadids entered 1919 needing to settle their differences with the Bolsheviks or risk the fate of the Alash Orda: a modernizing movement marginalized by its “allies” and the civil war.

Resources

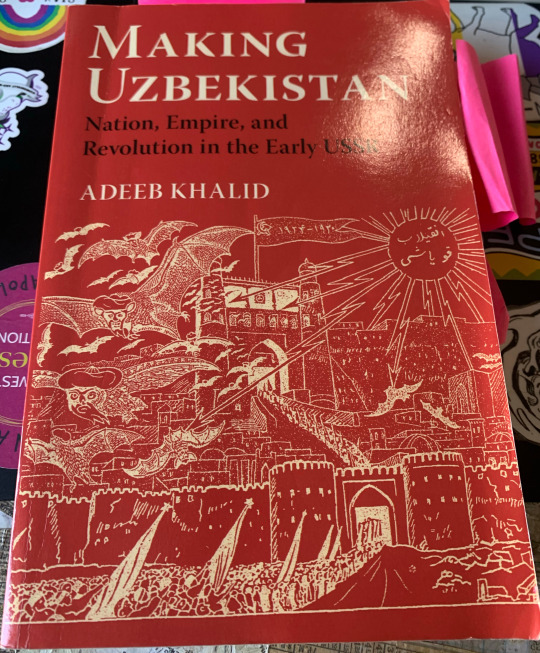

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865-1923 by Jeff Sahadeo

Central Asia: a History by Adeeb Khalid

#queer historian#central asia#central asian history#history blog#turar risqulov#turkestan#abdurauf fitrat#russian civil war#central asian civil wars#pyotr kobozev#Spotify

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Love for Central Asian Literature Part 1 – Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Cho’lpon

I’m currently working on a script for my history podcast, the Art of Asymmetrical Warfare, about three Central Asian literary giants: Abdurauf Fitrat, Abdulla Qodiry, and Abdulhamid Sulayman o’g’li Yusunov also known as Cho’lpon and it got me thinking about their influence on my historical interests, reading tastes, and writing style.

If you’re wondering why a podcast about asymmetrical warfare is talking about three Central Asian writers, you should check out my upcoming podcast episode. 😉

How I Became Interested in Central Asian Literature

My interest in Central Asia has been a long time percolating and it was just waiting for the right combination of sparks to turn it into a hyperfixation (sort of like my interest in the IRA). I went to the Virginia Military Institute for undergrad and majored in International Relations with a minor in National Security and my focus was on terrorism. So, I knew a lot about Afghanistan and Pakistan and the “classic” “terrorists” like the IRA, the FLN, Hamas, etc. and I knew of the five Central Asian states (one of my professors was banned for life from either Turkmenistan or Tajikistan and sort of life goals, but also please don’t ban me haha), but my brain bookmarked it, and I went on my merry way.

Then I went to University of Chicago for my masters, and I took my favorite class: Crime, the State, and Terrorism which focused on moments when crime, government, and terrorism intersect. This brought me back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, but this time focusing on the drug trade which led me to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and their ties to the Taliban and it was sort of like an awakening. I suddenly had five post-Soviet states (if you know me, you’ll know I’m fascinated by post-Soviet states) with connections to the drug trade (another interest of mine) and influenced by Persian and Turkic identities. I was also writing a scifi series at the time that included a team of Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian scientists and officers, so the interest came at the right time to hook my brain. Actually, if you buy my friend’s EzraArndtWrites upcoming “My Say in the Matter” anthology, you’ll read a short story featuring Ruslan, my bisexual, Sunni Muslim, Uzbek doctor who was inspired by my sudden interest in Central Asia.

Hamid Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance

I wanted to know more beyond the drug trade and usually when I try to learn about a place whether it be Poland, Ireland, or Uzbekistan, I go to their music and literature. This led me to one of my all-time favorite writers Hamid Ismailov and my favorite publishers Tilted Axis Press.

Tilted Axis Press is a British publisher who specializes in publishing works by mainly Asian, although not only Asian writers, translated into English. They publish about six books a year and you can purchase their yearly bundle which guarantees you’ll get all six books plus whatever else they publish throughout the year. I’ve purchased the bundle two years in a row, and I haven’t regretted it. The literature and writers you’re introduced to are amazing and you probably won’t normally have found unless you were looking specifically for these types of books.

Hamid Ismailov is an Uzbek writer who was banished from Uzbekistan for “overly democratic tendencies”. He wrote for BBC for years and published several books in Russian and Uzbek. A good number of his books have been translated into English and can be found either through Tilted Axis or any other bookstore/bookseller. Some of my favorites include Dead Lake, the Manaschi, the Underground, and the book that inspired everything the Devils’ Dance.

Tilted Axis’ translation of The Devils’ Dance came out the same year I was working on my masters, and I bought it because it is a fictional account of Abdulla Qodiriy’s last days while in a Soviet prison. He goes through several interrogations and runs into his fellow writers and friends: Fitrat and Cho’lpon. Qodiriy is written as detached from events while Cho’lpon comes across as very sarcastic, as if this is all a game, and Fitrat is interestingly resigned to the Soviet’s games but seems to have some fight in him. Qodiry distracts himself from the horrors around him by thinking about his unwritten novel (which he really was working on when he was arrested by the NVKD). His novel focuses on Oyxon, a young woman forced to marry three khans during the Great Game. His daydreaming takes a power of its own and he occasionally slips back to talk with historical figures such as Charles Stoddart and Arthur Connolly-two British officers who were murdered by the Khan of Bukhara (not a 100% convinced they didn’t have it coming).

We spend half of the narrative with Qodiriy and the other half with Oyxon as she is taken from her home and thrown into the royal court of Kokand’s khans where she is raped and mistreated and has to survive the uncertain times of Central Asia during the Great Game. She is passed from Umar, the father, to Madali, the son, to the conquering Khan of Bukhara, Nasrullah who eventually murders her and her children. From a historical perspective, I have a lot of questions about Nasrullah because a lot of sources write him off as a cruel tyrant and nothing more which usually means there’s more…Before Oyxon and Qodiriy are taken to their deaths, there is a poignant scene where the two timelines merge into one that will stay with you long after the novel is over.

The book is a masterpiece exploring themes of colonialism, liberty, powerlessness in face of overwhelming might, the power of the human mind and spirit, the endurance of ideas, even when burned and “lost”, as well as being a powerful historical fiction about two disruptive periods in Central Asian history. It’s also a love letter to the three literary giants of Uzbek fiction: Abdurauf Fitrat: a statesmen who crafted the Turkic identity of Uzbekistan, a playwright and statesmen, Abdulla Qodiriy who created the first Uzbek novel (O’tgan Kunar which was recently translated by Mark Reese and can be bought in most bookstores), and Cho’lpon who created modern Uzbek poetry (you can buy his only novel Night translated by Christopher Fort and a collection of his poems 12 Ghazals by Alisher Navoiy and 14 Poems by Abdulhamid Cho’lpon translated by Andrew Staniland, Aidakhon Bumatova, and Avazkhon Khaydarov in any bookstore).

City of Kokand circa 1840-1888, thanks to Wikicommons

All three men were Jadids (modern Muslim reformers) who worked with the Bolsheviks to stabilize Central Asia, helped create the borders of the five modern Central Asian states, and were murdered by the Soviets during Stalin’s Great Purge of the 1930s. It was illegal to publish their work until the glasnost. Check out my history podcast to learn more about the Jadids and the Russian and Central Asian Civil Wars.

From a literary perspective however, Ismailov wrote the Devils’ Dance similarly to Qodiriy’s own O’tgan Kunlar and Cho’lpon’s Night (whereas Ismailov’s other books: Dead Lake and the Underground are more Soviet era Central Asian literature and his newest book the Manaschi is more post-Soviet). Like Qodiriy and Cho’lpon, Ismailov writes about MCs who are not the master of his own fate, but instead are going through the motions of a fate already written, one of his MCs is a woman unfairly caught in a misogynistic system that uses women as it sees fit (although I would argue that Hamid gives his women characters more agency than either Qodiry and Cho’lpon), and he writes about the corruption and inefficiencies of whatever government agency is in control at the time – whether it be a Russian, a Khan, or an indigenous agent of said government. All three books end in death, although only Cho’lpon’s Night and Ismailov’s the Devils’ Dance end in a farce of a trial. Even stylistically Ismailov mimics the rich and dense language of Qodiriy whereas I find Cho’lpon’s style crisper although no less rich for it.

Abdurauf Fitrat’s Downfall of Shaytan

While Ismailov led me down a historical rabbit hole which is captured on my history podcast, I also wanted to see if any of Fitrat’s, Qodiry’s, or Cho’lpon’s work had been translated into English.

So far, I can’t find anything by Fitrat except excerpts in the Devils’ Dance and Making Uzbekistan by Adeeb Khalid (one of my all-time favorite history books by one of my favorite scholars who also happens to be very kind and patience and I still can’t believe I interviewed him for my podcast).

Fitrat wrote a specific play I really want to read called Shaytonning Tangriga Isyoni which Dr. Khalid translated as Shaytan’s Revolt Against God. According to the summary provided by Dr. Khalid it is a challenging take on the Islamic version of Satan’s downfall.

According to Dr. Khalid, in Islamic cosmology God created angels from light and jinns from fire and they could only worship God. When God made Adam, He commanded all angels and jinn to bow before him. Azazel (who would become Shaytan) refused claiming he was better than Adam who was made out of clay. He was cast out of heaven and became Shaytan/Iblis.

Fitrat reimagines Shaytan’s defiance as heroic. He is disgusted by the angels’ submissive nature and God’s ability to create anything and yet he chooses to create servants. Azazel has seen God’s plan to create another being out of clay and have the angels worship him as well, which Azazel sees as a betrayal on God’s part. Gabriel, Michael, and Azrael try to convince Azazel to see reason and instead he brings his grievance to the other angels who are confused. God intervenes and the angels give in, but Azazel continues to defy God. God strips him of his angelic nature, and he turns into Shaytan who warns Adam of God’s treacherous nature and vows to free him and all other creatures from God’s trickery.

Doesn’t it sound amazing?! Fitrat has outdone Milton in terms of completely overturning God’s and Satan/Shaytan’s rules (also no wonder he was marked for execution right? Complete firebrand and pain in the ass (and I mean that with love)) and I really want to read it. So, either someone needs to translate this into English, or I need to learn Persian/Uzbek, which ever happens first, haha (judging on how my Russian is going…)

Abdulla Qodiry’s O’tgan Kunlar

While I can’t find any of Fitrat’s work in English, there have been two translations of Abdulla Qodiriy’s novel and the first ever Uzbek novel O’tgan Kunlar. In English, the title translates as Days Gone By or Bygone Days. There are two translates out there: Days Gone By translated by Carol Ermakova, which is the version I’ve read, and Otgun Kunlar by Mark Reese, which I haven’t read yet but I’ve heard him speak (and actually spoke to him about his translation – thank you Oxus Society) so you can’t go wrong with either one.

O’tgan Kunlar is an epic novel set in the Kokand Khanate in the 18th century and is about Otabek and his love Kumush. There’s also a corrupt official, Hamid who hates Otabek because Otabek is a former who wants to change the society Hamid benefits from. Hamid tries to get Otabek killed for treason because of his reformist believes, but the overthrow of the corrupt leader of Tashkent (who Otabek worked for) saves Otabek’s life. However, the corrupt leader’s machinations convince the Khan to declare war against the Kipchaks people, who are massacred. Otabek and his father vehemently disagree with the massacre of the Kipchaks.

Once Otabek is released and gets revenge against Hamid, he marries Kumush without his parent’s approval and is torn between the two families. His mother hates Kumush and forces him to take a second wife, Zainab. Obviously, things go terribly wrong as Otabek doesn’t even like Zainab and Kumush doesn’t know how to feel about her husband having a second wife. Zainab hates her position within the household and eventually poisons Kumush.

Abdulla Qodiriy thanks to Wikicommons

O’tgan Kunlar is considered to be an Uzbek masterpiece that is central to understanding Uzbekistan. Not only is it a great tragic love story, but it also highlights some of the things Qodiriy was thinking about as he engaged with other Jadids. Just as Otabek argued for reforms especially in the educational, social, and familial realms, the Jadids were making the same arguments. We can also see the Jadid’s struggle with the ulama and the merchants in Otabek’s struggle with Hamid. Qodiry attempts to capture the struggle women went through by writing about the horrors for arrange marriages and polygamy, but Kumush is an idealized version of a woman. She is the pure “virgin” like Margarete from Faust while the other two female characters; Otabek’s mother and Zainab are twisted, bitter woman who hurt those they “love”. One could argue they’ve been corrupted by the society they live in, but they also lack the depth of Otabek and even his father.

One of the most interesting parts of the novel is the massacre of the Kipchaks because it is written as the horror it was and both Otabek and his father condemn the action. His father even claims that there is no sense if hating a whole race for aren’t we all human? Central Asia is a vast land full of different peoples who share common, but divergent histories and while these differences have led to massacres, there have also been moments of living peacefully together. It’s interesting that Qodiriy would pick up that thread and make it a major part of his novel because this was written during the Russian Civil Wars and the attempts to create modern states in Central Asia. The Bolsheviks really pushed the indigenous people of Central Asia to create ethnic and racial identities they could then use to better manage the region and so one wonders if Qodiriy is responding to this idea of dividing the region instead of uniting it.

Cho’lpon’s Night

While O’tgan Kunlar is a beautiful book and Qodiriy is a masterful writer, I prefer Cho’lpon’s Night (although don’t tell anyone). Night was supposed to be a duology, but Cho’lpon was murdered before he could finish the second book. Cho’lpon wrote Night in 1934, after years of being attacked as a nationalist. It was a seemingly earnest attempt to get into the Soviet’s good graces. Instead, he would be murdered along with Qodiriy and Fitrat in 1938.

Night is about Zebi, a young woman, who is forced to marry the Russian affiliated colonial official Akbarali mingboshi. The marriage is arranged by Miryoqub, Akbarali’s retainer. Akbarali already has three wives and, like in O’tgan Kunlar, adding a new wife causes lots of problems in the household. Meanwhile Miryoqub falls in love with a Russian prostitute named Maria and they plan to flee together. While they are fleeing they met a Jadid named Sharafuddin Xo’Jaev and Miryoqub becomes a Jadids. Meanwhile Akbarali’s wives conspire against Zebi and attempt to poison her but she unwittingly gives it to Akbarali instead. Zebi is arrested and found guilty of murdering her husband and sentenced to exile in Siberia. The book ends with Zebi’s father, who encouraged her marriage to Akbarali, is driven made by his daughters fate and murders a sufi master while Zebi’s mother goes mad, wandering the streets and singing about her daughter.

Like Qodiriy, Cho’lpon is interested in examining governmental corruption, the need for reform, and women’s plight, but Cho’lpon is less resolute than Qodiriy. Cho’lpon’s novel is constructed similar to poetry: an indirect attempt to capture something that is concrete only for a moment.

His characters are own irresolute or ignorant of important pieces of information meaning they are never truly in full control of their fates. Even Miryoqub’s conversion to Jadidism is to be understood as a step in his self-discovery. In Cho’lpon’s world, no one is ever truly done discovering aspects of themselves and no one will ever have true knowledge to avoid tragedy.

Cho'lpon courtesy of Wikicommons

It is interesting to read Night as Cho’lpon’s own insecurity and anxiety about his own fate and the fate of his fellow countrymen as Stalin seemingly paused persecuting those who displeased him. While Qodiriy crafted and wrote O’tgan Kunlar in the 1920s, which were unstable because of civil war, but promised something greater as the Jadids and Bolsheviks regained control over the region, Cho’lpon wrote Night during the height of Stalin’s Great Terror, most likely knowing he would be arrested and executed soon.

Both novels are beautifully written historical novels about a beautiful region, but I prefer Cho’lpon’s poetic prose and uncertainty.

Conclusion

Reading the works of Fitrat, Qodiriy, and Cho'lpon not only introduced me to a history I knew little about, but also introduced me to a whole literature I never knew existed. The books mentioned in this blog post are beautiful pieces literature and will challenge how you see the world and how much literature we miss out on when we don't read beyond authors who work in our native tongues.

The canon of Central Asian literature is immense, with only a handful of books and poems translated into English. I hope more works are translated so other people can engage with these books and poems and learn about these writers and the circumstances that shaped them. And, if you haven't, go check out Tilted Axis who are doing amazing work translating books so people can engage with them.

If you're enjoying this blog, please join my patreon or donate to my ko-fi

#central asian history#central asian literature#abdurauf fitrat#abdulla qodiriy#cho'lpon#O'tgan Kunlar#Days Gone by#Night#Hamid Ismailov#the Devils' Dance#Soviet Union#Soviet Central Asia#Uzbekistan

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chairman of the Fars House of Representatives: A bright future awaits the province

Chairman of the Fars House of Representatives: A bright future awaits the province

According to the representative office of Shiraz and Zarghan in the parliament, Alireza Pakfitrat, who spoke with the representative of the Supreme Leader in the Islamic Consultative Assembly, the governor and other executives in the Islamic Consultative Assembly on Thursday, increased the capacity of representatives and managers in Fars to develop The province considered it important.

The…

View On WordPress

#Alireza Pak Fitrat#awaits#bright#Chairman#Fars#Fars Governorate#Fars province#Friday Imam of Shiraz#future#House#Member of the Islamic Consultative Assembly#Ministry of Roads and City Planning#Parliament#province#Representatives#Shiraz#زرقان#فارس

0 notes

Text

Kitni ajeeb hoti hai insaan ki fitrat, Nishaaniyon ko mehfuz rakh kar insaan kho deta hai.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

South Asian Music Recs 2 fast 2 furious

India (pt 2)

Soulmate (genre: blues rock): formed in 2003, based in shillong. they mostly sing in english. i would recommend love you, voodoo woman, shillong (sier lapalang)

Indian Ocean (genre: multi. mostly jazz and rock and folk fusion): formed in 1990, based in delhi. they sing in multiple languages. i would recommend bagh aayore, shoonya, jaadu maaya

Moheener Ghoraguli (genre: multi; rock (folk and blues), jazz, baul, american folk): formed in 1975, based in kolkata. they sang in bengali. i would recommend ei shomoy amar shomoy, amar priyo caffe, sei phuler daal

chandrabindoo (genre: rock, multi): formed in 1998, based in kolkata. they sing in bengali. famous music composer pritam was a part of chandrabindoo! recommended: hridoy, geet gobindo, ami amar mone

Pakistan:

Junoon (genre: sufi rock): formed in 1990, based in lahore and nyc. multilingual. i would recommend: sayonee, yaar bina, azadi

Entity Paradigm (genre: rock): formed in 2000 (but they kept breaking up and rebanding every few years. also entity and paradigm used to be separate bands till they joined. yes this is the one with fawad khan. this is very mainstream. (<- girl saying this as if half the others are Not) anyway), based in lahore. they mostly sing in urdu afaik. recommended: hamesha, waqt, fitrat

Mekaal Hasan Band (genre: sufi rock, alternative rock): formed in 2001, based in lahore. they are multilingual, but mostly urdu afaik. recommended: raba, ranjha, ghunghat

noori: formed in 1996, based in lahore. multilingual. recommended: yariyaan, meray log, dil ki qasam

part 1

#rest of south asia prolly dropping soon yahoo (in parts. duh)!#pakistanis look away rq this is such a basic bitch list of your rock groups. i can do better. i promise. please drop recs i would love tjem#music#india#pakistan#desiblr#rock music#fusion music#sufi music#indian music#pakistani music#folk music#english music#bengali music#music recs#yeah bro idk what else 2 tag this w

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Raat si fitrat hai meri , aur chand si tu"

(Bin ek duje adhure mai aur tu)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

when anonymous said "waqt badal sakta hai insaan ki fitrat nahi" and then thomas shelby said "you can change what you do but you cannot change what you want"

#romantic academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#escapism#romanticism#light academia#bookblr#books & libraries#bookworm#text#poetsandwriters#poetry#aesthetic#dark academia quotes#bibliophile#reading#spilled ink#literature quotes

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wo nahi meri magar uss se mohabbat hai to hai

Ye agar rasmo riwajo se bagawat hai to hai

Sach ko maine sach kaha jab keh diya to keh diya

Ab zamaane ki nazron mein ye himakat hai to hai

Kab kaha maine ke wo mil jaye mujh ko me usse

Gair na hojaye wo, bass itni Hasrat hai to hai

Jal gaya parwana agar to kya khata hai shamma ki

Raat bhar jalna jalaana, uss ki qismat hai to hai

Dost ban ke dushmano sa satati hai mujhe

Phir bhi uss zalim pe marrna apni fitrat hai to hai

Door the aur door hain, har dam zameen-o-asmaan

Dooriyon ke baad bhi dono mein qurbat hai to hai.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

my amma often recites a sher by Allama Iqbal Saheb instead of saying, "bolo kam,karo zyada"

amal se zindagii bantii hai jannat bhii jahannam bhii

ye KHaakii apnii fitrat me.n na nuurii hai na naarii hai

-ALLAMA IQBAL

#allama iqbal#ishq poetry#urdu poetry#urdu literature#hindi poetry#hindi shayari#literature#urdu stuff#shayari#poetry#poets on tumblr#writers and poets#poetic#dead poets society#poems#urdu sher

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 50 – After the Russian Civil War: The Fall of the Alash Orda and the Jadids 1925-1938

For the European Soviets, the creation of the five Central Asian states was a “second revolution,” one that strengthened their presence and power within the region. Gone were the days when they’d have to compromise on the cultural and religious fronts. Instead, they could take advantage of the centralization of government to implement true Communist reforms and initiatives. Its biggest threat was the cadre of nationally-minded intelligentsia. By 1926, a war had been declared against the Alash Orda and the Jadids. It was initiated by the OGPU and spearheaded by indigenous actors, some who had been Jadids themselves or were educated by them, who wanted to prove their Communist credentials. However, the OGPU and European Soviets didn’t trust these new attack dogs, finding an ever increasingly large number of local actors who were guilty of nationalism. And thus, a fake conspiracy was created that grew so large everyone lost control of it until it finally ate itself to a painful and bloody death.

The First Arrests

It all started in January 1925, when the OGPU created the Commission for Working Out Questions on Attracting the Party’s Attention to the Work of the OGPU in the Struggle with Bourgeois-Nationalist Groups and with Counter-Revolutionary Ideology. This commission’s goal was to root out a nationalist and counter-revolutionary conspiracy and reported it to the higher ups as proof that the local actors could not be trusted. As Lev Nikolaevich Bel’skii an OGPU officer in Central Asia, explained:

“it was no secret to anyone” that those who “fought us for five years…have not been beaten either physically, economically, or spiritually and that their influence on the masses is still enormous” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 319

This predicament worsened by the “petit bourgeois governments” of the Central Asian states, who, “wanted to insure themselves against Soviet influence and the attraction of the model of Soviet rule in Central Asia” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 319). He further explained that the OGPU’s task was

“a harsh struggle with the malicious national intelligentsia by way of revealing [to the masses] their pan-Islamic and their sell-out-anglophile essence” Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 319

Of course, they made their jobs easier and harder by defining nationalism incredibly broadly. They claimed that nationalism could cover everything from outright condemnation of the Soviet order to expressions of discontent with the pace the Soviet polices were being implemented. They viewed korenizatsiia (which was supposed to integrate local actors into the Soviet system) as a “manifestation of the contemporary tactic of the anti-Soviet struggle of Uzbek nationalists: the infiltration of the Soviet apparat and the party, the preparation of youth, etc.” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 319,)

What is really interesting about that last quote is the fear of infiltration or impurity. We even see the ever-popular argument that the indigenous actors were “corrupting the youth” and turning them against Communism. It’s an interesting saying the quiet part out loud moment: the OGPU were afraid of being contaminated by the local actors and that any apparatus that relied on Central Asians could never truly be communist.

In his book, the Veiled Empire, Douglas Northrop argues that by 1926 the Soviets were identifying themselves in opposition to their Central Asian counterparts. I’ve talked a bit about this in Episode 48, but there was this nagging feeling that as Europeans and as vanguards of the Communist revolution they had to be better than their Central Asian counterparts and if Communism wasn’t really working out in Central Asia it’s because the heart of the Communist apparatus had been infected by the local actors. And thus, the OGPU could prove itself as a true Communist bureau by finding this secret conspiracy to infiltrate and destroy Communism from the inside out.

In spring 1926, the OGPU arrested several people who had been members of the Kokand Autonomy, but didn’t join the Soviet apparatuses of power. The OGPU claimed that they were “former leaders of armed struggle against Soviet power” (pg. 320, Making Uzbekistan) but several members of the Samaqand intellectuals recognized these arrests as an “ill-fated colonial policy of Soviet power, its tendency to cleave the national intelligentsia for colonial goals” (pg. 340, Making Uzbekistan)

A Society Turns on Itself

The OGPU arrests triggered a new series of attacks against the Jadids. Akmal Ikromov (Fayzulla Xo’jayev’s rival) and his Young Communists publicly attacked the Jadids for failing to align their previous reforms and activists to Communist principles (which would have been impossible because class hadn’t meant anything in pre-1920 Central Asia and there was no tradition of political organization along socialist lines at the time). Ikromov also called the Jadids the mouthpieces of national bourgeoisie who had resisted Soviet for so long by using the ideology of Turanism, Turkism, and Islamism, and had gone as far as calling for help from the Basmachi and English imperialists.

Several articles attacked the Jadids, proclaiming that there were two groups of intellectuals: those who developed before the revolution and were thus “nationalists and representatives of mercantile capital” and those who developed during Soviet rule and were thus servants of the workers and the peasants. The Jadids were denounced for being involved with members the Soviets deemed as reactionary, counter-revolutionary, and dangerous.

A few indigenous Soviets argued that the Jadids could still be of some use. Abdulhay Tojiyev, Secretary of the Tashkent obkom of the party and a Young Communists wrote:

“Of course, [the party] does not want to cast them aside or to have no dealings with them. It would be wrong to do so. Of course, we have to use those old intellectuals who can be used, to work those who can be worked” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 322

Rahimjon Ino’gamov, the Young Communist commissar for education, wrote:

“Our task should be to turn intellectuals who are close to the ideals of the Soviets into true servants of the Soviet order” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 322

This sentiment however, earned Rahimjon the wrath of Ikromov and other Young Communists and he was marked as a nationalist who provided “support to the nationalist intelligentsia” He was demoted to a low-level position in a rural village and was persecuted throughout his life. Soon there was no one to defend the Jadids except for the Jadids themselves.

Fayzulla Xo'jayev

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a men with black hair, a sharp nose, and a grey suit.]

Fayzulla took the lead in trying to defend his Jadid comrades. He shielded Fitrat from Ikromov’s attacks, claiming that Fitrat’s books should continue to be published because “Fitrat’s books are the property of our culture and do not contradict our policy” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 324). He argued that the Jadids were not a bourgeois movement but a semi proletarian group. It wasn’t a homogeneous entity that could be painted with one brush. Some Jadids turned their backs on communism, but others embraced communism. His arguments didn’t go far and instead opened him up to attacks by Ikromov and the historian P. G. Galuzo who accused him of not using Marxist categories in his analysis and for turning the Young Bukharans into revolutionaries and Communists. Xo’jayev was forced to amend his analysis, but he remained in power – for now. It’s unclear if he ever realized how fragile his hold on power was.

The attacks against the Jadids reached fever pitch during the Second Uzbekistan Conference of Culture Workers in October 1927. Ikromov attacked Vadud Mahmud (the jerk who was like Tajiks don’t exist) for being a nationalist. He riled the crowd up until they shouted:

“Enough! Away with such people! Vadud get lost!” until Vadud left. Botu, a Young Communist wrote, “Red cultural workers of Uzbekistan shamed an opponent of proletarian ideology and kicked him out of their midst” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 326

By 1927, the European Communists had a stranglehold on the local press, and they used their reporters to spread communism and be the front-line soldiers in their battle against the Jadids. These correspondents were often beaten, threatened, and sometimes killed for their work, but the Soviets did their best to protect them (even making it illegal to reveal the identity of these correspondents).

The Central Asian Bureau purged books they deemed harmful and discussed finally close the maktabs and madrassas for good. They placed their own handpick workers into the position of editors in several newspapers and slowly exerted control over what was and wasn’t published. Using their control over the press, the European Soviets steamrolled their own understanding of their own history on the Central Asians.

Any desire to talk about Central Asia’s unique position, needs, and development were overwritten was a “universal” (and Russian centric) version of the October Revolution. The true revolution arrived in Central Asia when the Tashkent Soviet took over Tashkent (never mind the disaster they were) and thus people could be persecuted for not lacking proletarian credentials in a society without proletariats. Any attempt to center the work of the local actors was decreed as nationalist. Instead, one had to only acknowledge the good work of the Russians who brought communism and salvation with them.

On the literary front, there was a new crop of writers who spoke Communist better than their own counterparts. Like the Young Communists, they saw themselves as the true guardians of Communism. Some like G’afur G’ulom, Oybek, and Hamid Olimjon would become the fathers of Soviet Union Literature in Central Asia. Others such as Botu and Ziyo Said were purged but remembered while others such as Qamchinbek, Anqaboy, or Amala-xonim, the first woman prose writer in Uzbek, have been almost forgotten. Some of these new Soviet writers had been taught by Jadids and may have been on friendly terms with them before the Soviet Union made it clear that to prove oneself a communist one had to destroy the nationalists.

Botu in particular, had a very violent break from the Jadids attacking Cho’lpon in publicly, proclaiming:

“You are a slave to yourself, I am

my own force

I visit your thoughts, your dreams in

nonexistence.

Your plan against light, your cause is

hollow

My cause commands fighting your cause.” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 333)

He argued that the Jadids were confined to the limits of “madrasa literature” and after the revolution “continued to fill the minds of schoolchildren with the poison of homeland and nation” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 333)

People loved to attack Cho’lpon actually. If it wasn’t Fitrat, it was Cho’lpon (poor Cho’lpon). Olim Sharafiddinov, a member of the new literary class, once wrote: Who is Cho’lpon? Whose poet is he? Cho’lpon is a poet of the nationalist, patriotic, pessimist, intelligentsia. His ideology is the ideology of this group” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334). He argued that Cho’lpon saw all Russians as colonizers and blamed them for “all wretchedness afflicting Uzbekistan” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 334).

Usmonxon Eshonxo’jayev, a childhood friend of Cho’lpon, piled on adding:

“The defect and harmfulness of Cho’lpon’s poetic lies in its ideology…which from the point of view of our time is reactionary…the Poet is an idealist and an individualist, and therefore sees every political and social event not from the side of the masses but from his own personal point of view” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 335

The Alash Orda weren’t faring any better in Kazakhstan. Uraz Isaev, a European Communist argued that the Alash Orda were a really the beginnings of a bourgeois class in Kazakhstan and attacked them for siding with the White Army, “the most inveterate enemies of the revolution.” (Maria Blackwood, Personal Experiences, pg. 139). He further argued that:

“We should not think that former Alash-Ordists represent a stiff and indivisible whole. There are some incorrigible political hunchbacks who will only be reformed by the grave. But there is also a certain segment of young people who were not especially active in Alash-Orda in the past, who under the influence of our positive work have noticeably changed their convictions. Such people must be more closely drawn into Soviet work and be given the opportunity to more actively cooperate with us.” - Maria Blackwood, Personal Experiences, pg. 139-140

While the goal was to try and rehabilitate those who had fallen from the Communist ideals, it was far more important to root out those who were using Communism to advance their own goals. He wrote:

“Such elements entered our Party either because they have the wrong address, or because they want to use the Party in their own interest. […] Such elements should be decisively removed from the Party ranks.” - Maria Blackwood, Personal Experiences, pg. 139-140

Two of these elements were Alikhan Bukeikhanov and Akhmet Baitursynov. Alikhan was banished to Moscow in 1923, but he was able to travel back and forth from 1923-1924, participating in scientific conferences, expeditions, and research. Despite his best efforts, he never managed to earn a permanent position within Kazakhstan. He was arrested several times between 1923 and the time of his death, July 1937.

Alikhan Bukeikhanov

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a man with black hair and a black mustache and goatee in a black suit and white shirt]

Akhmet Baitursynov would serve in several academic positions mostly in Kazakhstan and Siberia, before being arrested for the first time on June 2nd, 1929. He was held in Butyrskiy prison until E. Peshkova, Maxim Gorky’s wife, intervened and petitioned for his release. He would be arrested again in 1937 and executed along with several other Jadids and Alash Orda members.

Tactics to Survive the Onslaught

For the poor Jadids there weren’t many options to escape these attacks. Some retreated in scholarly work, others tried to recreate themselves in order to continue doing public work, and others made public statements of repentance and loyalty. Fitrat wrote a play in support of the land reform being carried out and Cho’lpon wrote a letter to the Second Congress of Culture Workers admitting he had had nationalist feelings in the past and promised to rectify his mistakes. Qodiriy retreated to fiction writing that was published despite being acknowledged as not Soviet enough while others tried to write Soviet only novels.

Poor Elbek was arrested by the OGPU in 1927 and was asked to write testimony about non-Soviet actors Jadids and Nationalists in Uzbekistan. Munavvar qori, who the Soviets hated, spoke at a conference of cultural workers in 1927, admitting his mistakes, and argued that many people who held power in the party were taught by the Jadids. He said:

“Over the course of thirty years, we could not carry out land reform and unveiling. The Bolshevik party has accomplished these in ten years…We are ready to support the revolution…One or two Jadids have sinned, but it is not good to tar all of them with the same brush” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 338

His plea was met with mockery, and he never made a public appearance again.

Others adopted a strategy of learned helplessness. In her book, Despite Cultures, Kassymbekova argues that when the Soviets complained about Central Asian “backwardness” or inability to implement and support Soviet goals, they were identifying a coping mechanism many people utilized to survive the upheaval that followed the Russian Revolution. If the Soviets could complain that Central Asians simply didn’t understand Communism or were purposely trying to impede progress, the Central Asian could claim that the Soviets had failed to teach them properly.

One time an Iranian Communist who was sent to Tajikistan to help with the Soviet program, apologized for his missteps, claiming, “I think that I have many defects, a lot of mistakes, a lot of misunderstanding, which need to be reeducated.” A Tajik Communist reportedly replied, “Too many defects will not do. A little bit is ok” (Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 2).

Living Within a Soviet Society

Kassymbekova makes a fascinating argument in her book, Despite Cultures, that the only way the Soviets could unite all their republics was to create the language of bureaucracy. This, however, was a stupefying, alienating language that many people simply couldn’t understand and thus it became a tool to obfuscate and condemn.

Kassymbekova argues that early communism depended on individual party members who were dedicated to communist principles. These individuals needed to embody these principles a hundred percent with the utmost purity. They had to have a complete understanding of communism and the politburo’s goals, and be able to identify the true roots of inequality. They were not bound by law or language because those were the tools of capitalism and thus it was ok to tell a lie if it furthered the Communist project. It was ok to work with class traitors for a while because it helped communism. It was action that proved truth. If a lie saved communism, then it was a pure act. If a lie hurt communism then it was punished.

The reliance on individual cadres allowed Soviets to claim they were anti-colonial and anti-capitalist which relied on institutions. This strategy was cheaper than building institutions from the ground up, it enabled mass-scale campaigns since communism depended on all individuals coming together for the greater good and if an individual resisted he was identified as a threat and treated accordingly. It allowed deputized individuals to spread throughout the wide terrain and bring communism to the most remote of villages. However, it also made communism dependent on the local leaders on the ground. A leader could get away with a lot as long as they kept up with agricultural and industrial demands. This also meant that communism wasn’t implemented consistently and left a wide range of experiences within the communist system.

The soviet leaders were idealized and had tremendous power but were constantly hounded and spied on to ensure they remained pure. This taught local leaders to speak “Bolshevik” to upper party leaders while pursuing whatever policies they wanted on the ground. For many people in Central Asia this meant learning the language while utilizing the Bolshevik’s assumption of backwardness to their favor.

This meant that words were no longer used as means of communication, violence was. If they didn’t like something, they violently punished the perpetrators. But that also meant guessing which crime someone was killed for, so no one was ever sure what Moscow really wanted and what it really detested.

Disgruntlement with the Soviet Order

Of course, attacking nationalism right after a nation had been created was counter-productive and the Soviets couldn’t ignore the persistence of colonial inequalities and ethnic division in the region. The lack of a local proletariat and the increase of fascination with having a nation led the OGPU to become obsessed with the rise of “pan-Uzbekism” and “chauvinism.”

Europeans continued to stream into Central Asia looking for work, many of the economic sectors were dominated by Europeans, and the Soviets with power and trust of the OGPU were the Europeans. This led to quiet disgruntlement with the failing of the new order. Some of the complaints the OGPU recorded were as follows:

“The Russians are conducting a chauvinist policy. In Tashkent, all factories are packed with Russians if an Uzbek ends up there, he is fired right away.”

“Ferghana’s peasantry is in a very difficult situation: colonists command everything. The situation is so catastrophic that one may expecting an uprising. The line of the CC in regard to the intelligentsia is incorrect, [and the struggle] with kolonizatorstvo is conducted indecisively” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 339-340

Worse of all were the whispers that because of the forced production of cotton, Uzbekistan had become nothing more than a red colony, like India or Egypt under British rule. A teacher in Tashkent told his students that Uzbekistan was “in fact, a colony that exports cotton as a raw material” (pg. 340, Making Uzbekistan). One student asked, “What is the difference between the English colony of India and the administration of Kazakhstan by Goloshchekin?” (Adeeb Khalid Making Uzbekistan, pg. 340).

A Kyrgyz official once called the Bolsheviks “Colonizers with Party Cards” (what a burn) because they never understood the local needs. They only pushed what they thought the region needed.

Sobir Qodirov, an accused member of a nationalist counter-revolutionary organization, wrote:

“The national policy of Soviet power in Uzbekistan we regard as colonial policy, as a continuation of the great power policies of Tsarism. Such a policy, in reality, provides for the well-being exclusively of the Russian nation at the expense of the exploitation of the indigenous population. Thus, for example, Europeans living in Uzbekistan find themselves in the most favorable situations, when the Uzbek part of the population is doomed to the most pitiable, beggarly existence.

…We consider that Uzbekistan has enough natural wealth and commodity production for it to be an independent economic unit, and consequently to have its own industry, both light and heavy.

We consider that Soviet power wittingly does not allow the development of independent industry in Uzbekistan exclusively because it seeks to keep Uzbekistan as a base for raw materials in order to extort its riches. In other words, Uzbekistan is a colony of inner Russia, supplying raw material for its industry.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 378

In 1929, Yodgor Sodiqov, a party member from Khujand, wrote to Stalin directly

“Peasants and artisans endure deprivation; they cannot complain, for they are afraid of arrest by the OGPU. But the cup of the peasantry’s patience is full to the brim. Waiting until it flows over is harmful. If the leadership of the party does not change and the people continue to be despised, then, without regard to my twelve years of work and the loss of my health in this work, I will consider myself to have left the party” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 378

Things were similar dire in Tajikistan, who had to deal with a weak infrastructure and government apparatus and constant Basmachi incursions. Their government was made out of Communists who were either in Tajikistan as a form of punishment or who had nowhere else to go. The Basmachi and questionable Communists drew a large number of OGPU into the region. Many officials actually wanted to leave Tajikistan, but the Soviets made it impossible to resettle. When that failed, the presence of the OGPU was enough to keep people in line. The OGPU was above the local government’s power, and this upset many officials. Two Soviet members in Tajikistan complained that:

“We have no authority! Our secret communication is being opened by the [O]GPU, our telegrams are not being sent. There is war against the Revolutionary Committee. You should either help us or remove us from Tajikistan” Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 49

The OGPU acted like cops always do. One time they kept an eyewitness prisoner for seven months. Another time a party member received several complaints about an OGPU member who:

“Pushed peasants off the road; they were half-dressed and half-shod with donkeys stuck in the mud up to their ears i.e., you surely know what kind of roads are here in winter. Moreover, he stopped at the mosque and raped a woman who was heading to a first-aid post. The peasants saw this and were shocked, and I have an eyewitness – the chief investigator. Does this not discredit the authority of the party and branches of the [O] GPU?” (Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 49

It is hard to tell how widespread this dissatisfaction was, but it made the Soviets paranoid, leading a massive purge in 1929.

Destroying Islam

For years, the Soviets uncomfortably tolerated Islam because they were afraid of sparking a mass exodus to the Basmachi ranks, but 1926 they launched a new initiative untie society and culture from Islam. In 1927, the Soviets officially closed all maktabs in the Central Asian states. However, the Soviet schools were not increased to handle the 35,000+ new students and so many kids simply went without an education. After dealing with the maktabs, they went after the madrasas, finalizing the nationalization of waqf land and cannibalizing the buildings for other purposes. Those they could not repurpose, they closed by 1928.

The Soviets also turned on the “progressive” ulama who they had relied on in early 1920s to help spread support of the Soviet reign. The OGPU worried that, to quote a report from the Kazakhstan central committee:

“Today’s clergy is not the clergy of five or ten years ago. It is a clergy that understands the moment of the struggle of labor with capital, of socialism with capitalism, going on in the country where socialism is being built, and adapts all its tactics to the current movement” (Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 346)

Basically, by educating the ulama about communism, they actually made them more powerful and dangerous. To counter their dangerous influence, the Soviets abolished the qazi courts and shariat administration in 1927. They increased rhetoric that placed all of the blame for the violence of the civil war on the ulama (even the reformist or progressive ulama) and the Basmachi. The Soviets argued that the Basmachi and ulama were united against the people of Central Asia (and absolving all Soviets and Europeans of violence they definitely committed).

Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy

[Image Description: A black and white picture of a bald man with a black mustache. He is wearing a tubeteika and a striped robe]

While the committees and executive were concerned with the maktabs and madrasas, lower-level Communists turned their attention to the mosques and shrines. This movement gathered considerable support amongst the local Soviets, forcing the central committees to support them or be called counter-revolutionary. The secretary of the Bukhara party committee wrote:

“Mosques were closed by decisions of party cells, by decisions of Komsomol cells, by decisions of rural soviets, of meetings of the poor or simply without any decision at all. Such an abominable situation continued from the beginning of 1927 to the end of 1928…the closing of mosques took on the character of a competition.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan,. pg. 353

Because this was led from the ground up, the closures were not as sudden or as effective as the closures of the maktabs or madrasas. When the Soviets couldn’t destroy a mosque, they repurposed them into clubs, Red Reading rooms, warehouses, schools, or stables for OGPU horses. The mosques closed in spurts between 1927 and 1929 and it picked up in the 30s as it became part of the collectivization efforts.

Shohimardon

Great violence could occur when the Soviets tried to destroy the mosques and shrines. One of the most famous examples was in March 1929 in the mountain village of Shohimardon in the Ferghana Valley. Jadid playwright, Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy was overseeing the destruction of the mazor attributed to Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law. The caretakers of the mazor were dozens of families of sheikhs and xo’jas. Hamza wanted to convert the mazor into a resort for the poor peasants. Hamza argued that the site was corrupt, claiming:

“The Xo’jas in the hamlet of Shohimardon have turned the fake grave of Ali into a resource and they rob the people with it. The sheikhs claim to have the key to paradise in their hands because of their descent from Hasan and Husain. They send those who do the proper sacrifice [and pay the sheikhs] to “paradise,” and those who don’t to “hell.” These sheikhs of Shohimnardon have to this day never worked, never labored, but, dressed in the garb of cunning, they have adopted the principles of Satan and, turning their rosaries, have fattened like the pigs of the Shohimardon steppe…They have poisoned the minds of workers with superstition and [now] feed off their possessions.” - Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 351

Hamza brought with him several peasants to march on the mazor, place a red flag on its cupola, and padlock the door. He also established a Red Teahouse and kiln, hiring thirty-five families to run the site and to crowd out the xo’jas. He threatened to call the red army unless the sheikhs publicly announced that they were indeed corrupt and feeding off the people and their misplaced faith. The standoff lasted throughout the winter of 1928, until in early March, on the evening of the end of Ramadan, Soviet police entered the mosque, took off the wall hangings, and arrested the muezzin. On March 17th, the demolition began. A crowd of three hundred people defended the shrine, disarmed the police, destroyed the red teahouse, and stoned Hamza to death.

The OGPU arrested 54 people and put them on public trial in June. 9 were executed, 16 sentenced to prison, 25 exiled to other parts of the Soviet Union, and 4 were acquitted.

Despite the fact that the Soviets were anti-clerical and anti-religions, the OGPU, of all people, noticed that the closing of mosques was causing too much disruption. They asked the central committees to try and quelch the closing of mosques. Even Akmal Ikromov said

“As it is, nowhere does the population trust Soviet power…if someone wants there be an uprising in Uzbekistan, then a few more such abominable facts will be enough.” Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan, pg. 353

Like the hujum, the unveiling of women, the closing of mosques was constructed without taking the local population in consideration, it quickly spiraled out of control because it was left to the lower ranks of the Soviet apparatus, and once it spiraled out of control it created flash points for people who were already upset with the Soviet regime, to violently vent their frustration and anger.

Collectivization

While the Soviets were trying to slowdown the hujum and closing of mosques, in 1929 they implemented maybe the most disruptive policy: collectivization. This policy was designed to establish Soviet control over the countryside and break all resistance. It would produce great violence and mass starvation. This same collectivization effort would create the Holodomor in Ukraine in 1930 and while Ukraine suffered the most in terms of the number of dead, the suffering in Kazakhstan, specifically, shouldn’t be underestimated. To give you a sense of perspective, the conservative estimate is that 3.9 million people died in Holodomor and the conservative estimate for the Kazakh famine is 1.5 to 2 million people. It’s estimated 30-40% of all Kazakhs died.. The Holodomor and the starvation of the Kazakhs were genocides.

The goal of collectivization was to collect individually owned farmlands and livestock into collective holdings controlled by the state. The idea was that the state would most effectively decide how the food should be distributed and you wouldn’t have pesky price gouging or shortages because the state (i.e., Stalin) was all knowing and never got anything wrong.

Turning Central Asia into an agricultural dispensary came out of the pain of the Russian empire collapsing and Moscow losing access to food in Ukraine, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. It was also a matter of self-sufficiency. If they could grow their own cotton, they wouldn’t have to import so much (cotton made up 1/3 of the values of all imports in 1924) and enable them to export more textiles (creating jobs in Russia proper as well). Central Asia, especially Kazakhstan, accounted for 75% of the Soviet Union’s domestic cotton supply, but it could never hope to meet the Soviet Union’s need. The Soviets imported 45% of their cotton fiber, meaning it made up 15% of all imports between 1924-1928. The world prices for cotton fluctuated widely, inspiring Stalin’s desire of “cotton independence.”

To increase cotton production, the Soviets fixed the purchase price of cotton to 2.5 and then 3.0 times the market price of grain from 1922 to 1926. Many Central Asian farmers and peasants took advantage of the lucrative prices, increasing cotton acreage from 171,255 acres in 1922 to 1,412,915 acres in 1926. The Soviets further encouraged cotton growth by offering various forms of aid such as agricultural credits, subsidies, farming implements, draft animals, and land-improvement aid. In 1928, the Komsomol even went as far as to create cotton holidays, declaring cotton as a key component of Uzbek honor, and cotton became the symbol of Uzbekistan.

In Tajikistan, cotton was identified as its pride and glory, “the happiness and hope of the Soviet Union” and “the measure of the republic’s achievement and successes” (Botakoz Kassymbekova, Despite Cultures, pg. 72). A Soviet official described Tajikistan’s role in growing cotton as: