#The inherent tragedy lies in the story of course

Text

Link is a conduit.

I love Link a lot. He's probably my favourite silent protagonist ever in every form he exists in.

But Link is simply a conduit.

Every action taken by Link is your own decision. You, the player, are using Link to your own ends.

Just as the plot uses him.

Just at the legends are using him.

(it must be tiring, to have no other choice than to allow yourself to be channeled by a hand not your own. It must be exhausting, to know that when you wake and have no control over your own body, that destruction is coming and there is nothing you can do but observe it all unravel around you.)

Link is a conduit.

But he has to fulfill his task. It's what the story demands.

#Tloz#The legend of zelda#Link#Momo writes stuff#Thanks Verse for putting this thought into my head#With that one AA fic you wrote#The inherent tragedy lies in the story of course#But it also lies in how there's nothing you can do to stop it#The story is already written#The story must play out#It is the same every single time#All you can do is watch it unfold#All you can do is hope your player will follow the path#(all you can hope is that the player will LEAVE)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

OFMD and the Sea as the Home of Runaways

So we don’t know when or why specifically that Ed went to sea in OFMD but I think as many fic writers have noted, it was probably linked to his “Kraken” killing of his father.

There’s a distinct possibility that Ed fled to sea that night. What would the alternative be, that he went home after? It’s certainly possible. There’s a possibility he lied to his mother actively or by omission when his father didn’t return home and only went to sea as a profession, completely unrelated, at some later point. There’s a possibility he didn’t lie and had to flee his mother’s recrimination. Honestly, there’s only a very narrow chance in my mind that he told the truth and was embraced for what he did by his mother and went to sea at some later point at his own pace.

But with regards to how Ed became a pirate, I personally think it’s more thematically resonant if he fled immediately after or was driven out immediately or soon after when his mother learned the truth. I come back to Olu’s point about how unlike Stede, most pirates are doing this job because they have to. Olu and Jim are runaways from Jackie’s wrath, for example. What Olu got wrong about Stede is that in a way, he didn’t have a “choice” either, he just had more privileges and wealth to cushion his flight to the sea. Because Stede is also a runaway, from his failed marriage and the soul-killing expectations of his upbringing.

I imagine if we delved into the past of the other crew members, we’d find more stories of runaways. It’s not a huge leap to imagine Lucius ran away to sea as the only place where he could love openly as he chose. It’s one reason he exhibits such sympathy for Stede, I believe, once he begins to understand more about who Stede is and what he was fleeing. Really, from a Doylist angle, it’ll be interesting to see if runaways as a theme is embraced for how and why pirates thematically exist in this universe and whether or not it links other crew members’ backstories.

Which brings me back to Ed. I think there would be thematic consistency and resonance if breaking the chains of his fathers abuse necessitated his flight to the sea. That he then proceeded to rise through the ranks on guts, brains, and raw talent is what makes his tale a triumph but with that seed of tragedy at its core that never went away. “Blackbeard” is a mask and a suit of armor.

We don’t have it confirmed yet, but I think a thematic link between Ed and Stede where both found the sea after fleeing a shattered home life of their own making could work. Of course, in each case it was done with varying degrees of violence (or perhaps not, Stede also in a way deprived his children of a father and his wife of a husband, depending on how much recrimination one wants to heap on him as compared to Ed depriving himself of a father and his mother of a husband, albeit one who “was a dick”). But as another meta commenter wrote very poignantly, there’s already a textual theme in the show that having trauma is such an inherent, expected part of being a pirate that it could be said that in the world of OFMD, to be a pirate is to have trauma. Perhaps, to be a pirate is also to be a runaway.

#ofmd meta#our flag means death#I’ll link the meta once I’m back at my computer this was typed with thumbs now lol

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cyrano: All the Words I Don’t Have

[The following essay contains SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Early on in Cyrano, Joe Wright’s delightfully maximalist musical adaptation of Edmund Rostand’s classic play, Christian—the dullest point of the story’s convoluted love triangle—laments (through song, naturally) his utter inability to articulate his feelings:

I’d give anything for someone to say / All the words I don’t have and I can’t put together / I’d give anything for someone to say to her / That she’s all I can think about / And I can’t live without her.

His distress is hardly unjustified: in the movie’s melodramatic setting, words are everything. Indeed, Roxanne, the object of Christian’s affections, somewhat foolishly correlates eloquence with outward beauty: “He is beautiful; he must therefore express himself beautifully.” Hers is the attitude of the archetypal “hopeless romantic”; from her perspective, the simple act of exchanging love letters is inherently intimate, sensual, and even outright erotic—in one particularly memorable scene, she literally writhes in borderline orgasmic euphoria as she reads her admirer’s poetry aloud, caressing her trembling body with the crumpled paper.

Roxanne’s beliefs are not totally naïve, however. For a woman of her relatively humble socioeconomic status, words represent some modicum of power—her only weapon against those that would prey upon her. When the amorous and arrogant Duke de Guiche attempts to force the issue of their “engagement,” for example, she manages to indirectly reject his advances with a few tactfully phrased lies and thinly veiled insults. Her wit is her sword, and she desires a partner that can match her skill in verbal fencing.

Thus, Christian’s metaphorical “muteness” is as great a disadvantage as his eponymous rival’s physical deformity; consequently, they must combine their respective talents in order to successfully woo this fair but uncompromising maiden:

My words upon your lips. I shall make you romantic, while you shall make me… handsome.

Of course, this deception ultimately renders their mutual “victory” hollow; Cyrano’s sentiments do not belong to Christian any more than Christian’s face belongs to Cyrano:

She told me that she loves me for my soul; you are my soul!

The film’s entire conflict, in fact, revolves around the most essential words of all: those that remain unspoken. Peter Dinklage and Haley Bennett subtly imply that each of their characters is painfully aware of the other’s silent pining; both are merely too afraid to acknowledge their obvious mutual attraction, lest they tarnish the platonic relationship that they’ve already built.

And their stubborn refusal to communicate honestly—to confront the undeniable truth—inevitably culminates in tragedy.

#Cyrano#Joe Wright#Peter Dinklage#Haley Bennett#Ben Mendelsohn#Edmund Rostand#musical#romance#film#writing#movie review

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

#JamesDonaldson On #MentalHealth - #Physician #Suicide Is A Public Health Crisis That Demands Immediate Support

by Trisha Minocha

Pixabay/Parentingupstream

Content warning: mentions of #suicideideation and #suicide.

#Physicians may appear to be flawlessly composed in their dapper white coats and clean stethoscopes swung around their necks. Their seamless discussion of medical jargon coupled with their collected appearance creates a powerful perception of excellence. However, #physicians’ portrayal of perfection couldn’t be farther from the truth.

2022 has been both a grueling and devastating year for #physicians with nearly one in ten #physicians experiencing #suicidalthoughts. In September of 2022, resident #physician Dr. Jing Mai took her own life after battling struggles with her #mentalhealth as a first-year #physician. It pains me to watch another young and spirited #physician fall into the cracks of an inherently broken system. I hope for Jing to find peace, and hope this tragedy propels change within the medical field.

Jing’s story is not uncommon. The statistics regarding #physician #suicide are alarming. Around 300 #physicians die by #suicide every year. The medical profession has repeatedly failed its own, reporting high #suicide rates among #doctors since 1858. The pressures of the medical field have pushed distraught #physicians to the limits of their emotional resilience. As we lose nearly one #doctor per day to #suicide, the neglect of #physician #mentalhealth has caused tragic and irreversible consequences that can only be ceased with a dramatic cultural reset in the medical field’s current approach to wellness.

Medical #schools and residency programs have acknowledged the emotional toll of medical training. Medical #students have wellness seminars embedded into their curriculum as institutions have begun to offer courses in mindfulness and #self-care. For instance, the University of California San Diego’s School of Medicine provides its #students with web-based screening along with educational resources centered around #mentalhealth and wellness. In 2003, residency hours were capped to 80 hours a week to alleviate #physician burnout. Despite these efforts, there has been no significant improvement in #physician #suicide and #mentalhealth outcomes. The exhaustive and pressurized nature of medicine continues to push #physician emotional boundaries beyond its limits. The medical community is in need of a necessary cultural shift. The healthcare field owes it to its #physicians to not only recognize its shortcomings, but to also generate tangible and impactful changes in the #mentalhealth sector.

The root of the problem lies in the healthcare industry’s general and stigmatized approach to #mentalwellness. #Doctors feel pressured to display a facade of physical and emotional competence. Stoic culture has been encouraged in medicine since the 1800s, with the first residency program at Johns Hopkins Hospital stressing the importance of emotional detachment among #physicians. While a physician’s composure is of great value, the appraisal of immense poise has resulted in the creation of an ultimately dehumanizing system that deprives its workers of raw emotion. #Healthcareworkers often suffer in silence due to the #stigma associated with experiencing #stress and #mentalillness. Nearly 50% of #female #physicians have disclosed that they have not sought out treatment despite meeting the criteria for #mentalillness. #Physicians are dissuaded from seeking necessary treatment due to the fear of reporting their diagnosis to the medical board as well as worries that their diagnosis would be perceived as shameful. In a community that has grown to shame emotion, #physicians work to masquerade as unblemished professionals at the cost of their own #mentalhealth. With only 13% of medical providers seeking treatment for their #pandemic-related #mentalhealthconcerns, the medical community’s current approach to wellness fails to dismantle the #stigma surrounding #mentalillness in medicine.

#James Donaldson notes:Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for #mentalhealthawarenessandsuicideprevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions. Us men need to not suffer in silence or drown our sorrows in alcohol, hang out at bars and strip joints, or get involved with drug use.Having gone through a recent bout of #depression and #suicidalthoughts myself, I realize now, that I can make a huge difference in the lives of so many by sharing my story, and by sharing various resources I come across as I work in this space. #http://bit.ly/JamesMentalHealthArticleOrder your copy of James Donaldson's latest book,#CelebratingYourGiftofLife:From The Verge of Suicide to a Life of Purpose and Joy

In order to effectively address #physician #mentalhealth concerns, we must first work to eradicate the shamefulness that surrounds #mentalillness among #physicians. Healthcare institutions fail to recognize that #depression, #anxiety and #suicidalideation can not simply be resolved through generalized wellness seminars. #Mentalhealth is distinct to the individual. The standardization of #mentalhealth education not only fails to effectively address one’s personal journey, but it also fails to ignite honest and open conversation. To combat a culture that suppresses both the discussion and expression of sentiment, we must allow individualized treatment to become the center of our approach to improving physician #mentalhealth.

To destigmatize #mentalillness among the medical community, healthcare institutions must foster personalized and authentic discussions regarding one’s mental wellbeing. #Doctors are not exempt from the complexities of human emotion. #Physicians should feel encouraged to share their vulnerabilities. The mere verbalization of fears and anxieties can improve one’s ability to better regulate their emotional experience. Likewise, encouraged discussion of personal burdens dismantles facades of composure and empowers physicians to seek necessary support. As medicine is inherently an emotionally taxing profession, the medical community must be unflagging in its efforts to encourage the honest discussion of #mentalhealth.

As we reflect upon the countless number of #physician lives lost to #suicide, let us remember and honor the life of Jing. Jing’s life was both beautiful and impactful. Her life embodied a young woman, driven and passionate, who had chosen to devote herself to medicine and #patient care. A cherished life, that tragically fell victim to the hostility of medicine. May we forever honor Jing’s story and memory. Life is so precious, and it’s sobering to say that we may see little change in #physician #suicide rates with the current #mental-wellness systems in place. The medical field cannot claim to be an industry of healing when it continuously fails to remedy its healers. Hundreds of our #physicians have died at the hands of the medical community.

Our #physicians deserve better. Jing deserved better. We owe it to Jing, and the hundreds of #doctors whose lives were also lost to #suicide, to ignite the change that allows us do better.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Syberia: The World Before. Passage and solution of all puzzles

💾 ►►► DOWNLOAD FILE 🔥🔥🔥

A lot is tied to the past here, there is even a full-fledged second character, a certain Dana Rose, whom the eternal protagonist of the series, Kate Walker, is looking for. Benoit Sokal did not betray himself here either, weaving a non-existent country right in the middle of Europe into real history. The threat of the Brown Shadows, the local Nazis, swells over the city of Wagen. Ethnic pogroms are brewing, while Dana is scheduled to have a big performance with the famous orchestra of automata, created by Hans Voralberg, who was passing by. Yes, again we are trying to find out about a person who may have been dead for a long time, but is such a trifle capable of stopping the brave heroine? Moreover, pretty soon she reunites with Oscar, who, starting from the second part, was the mascot of the series, and now he has also acquired a form to match the content — his new body is very cute. And no, this, of course, did not diminish his inherent causticity. Two narrative periods give the authors the opportunity to clearly show how the world changes over time. In particular, what does the lack of funding do to small countries: everyone in modern Wagen sells souvenirs, and the famous mechanical orchestra has not been working for a long time — they are going to computerize it, but there is no money in the budget. However, the charm of a small town remains in place in the XXI century. Ancient houses, flowers, mechanical trams that rise when climbing a mountain for the convenience of passengers are beautiful, and even very beautiful: the artists honestly worked out their bread and were not stingy with details. Why, even in comparison with the demo of this very game, progress is evident — the long downloads that irritated there have disappeared. But without falling into complete blackness or strange light strokes along the edges of buildings and characters, it would still be even better. Many different mechanisms are just waiting to be twisted and poked from all sides. The series holds its own: the puzzles here are not too difficult, but interesting. Adds variety and switching between times, and the ability to play for Oscar in different variations. There are even secondary tasks, usually reduced to the extraction of some new information that reveals the story in more detail. But the further history moves, the more clearly it becomes clear that behind all these time jumps lies a simple truth. And there, and there, Kate stubbornly follows in the footsteps of someone who may not be alive. Only in the debut game of the series did Kate have a personal arc, the heroine changed over the course of the story and did an act that she had never done before. In Syberia: The World Before, everything is the same, only the heroine has nowhere to change, so all the experiences, troubles and tragedies go to Dana Rose, and Walker remains the role of a conductor in the plot. Only now the plot is just another episode of a big series. For More Games Click Here. Read More about New Games Here. If you face any kind of issue or any type of problem in running the Game then please feel free to comment down below, we will reply as soon as possible. Your email address will not be published. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Running in a circle. CPU: Core i RAM: 8 GB. OS: Windows 7 or higher. Download Game. Related Items:. Click to comment. Leave a Reply Cancel reply Your email address will not be published. Updated version of Resident Evil 3 received an age rating. Most Popular. To Top. We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits. However, you may visit "Cookie Settings" to provide a controlled consent. Cookie Settings Accept All. Manage consent. Close Privacy Overview This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. But opting out of some of these cookies may affect your browsing experience. Necessary Necessary. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. These cookies ensure basic functionalities and security features of the website, anonymously. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". It does not store any personal data. Functional Functional. Functional cookies help to perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collect feedbacks, and other third-party features. Performance Performance. Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors. Analytics Analytics. Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc. Advertisement Advertisement. Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with relevant ads and marketing campaigns. These cookies track visitors across websites and collect information to provide customized ads. Others Others. Other uncategorized cookies are those that are being analyzed and have not been classified into a category as yet. The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies.

1 note

·

View note

Text

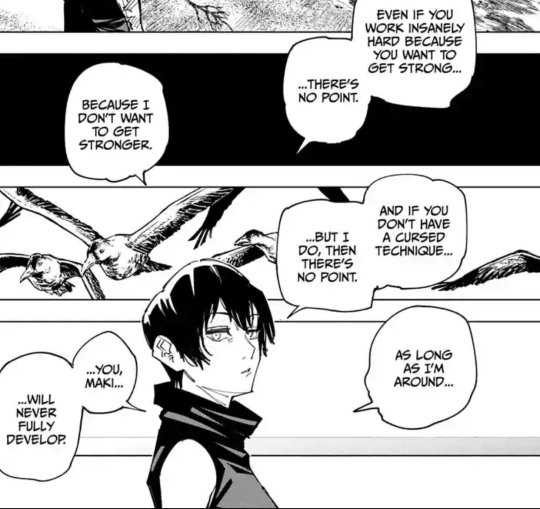

JJK 149. Mai Zen'in

It’s fascinating for a battle shounen manga to have a character like Mai who is diametrically opposed to the ideals of strength and self-improvement that are usually valourized in this genre. Mai doesn't die because she can’t get stronger, but because she doesn’t want to. And although that attitude is evidently incompatible with an existence within the world and situation she found herself in, there is no negative value judgment imposed by the narrative itself condemning her unwillingness to unlock her "full potential".

JJK has always foregrounded competing worldviews and how individuals’ different perspectives and values can either coexist or conflict with others. Maki's ambition to transform the Zen'in clan vs. the Zen'ins' regressive conservatism; Gojou's vision for the jujutsu world vs. the higher ups' ; Yuji's "I want to save everyone" vs. Megumi's "I choose who I save" ; Mei Mei's "I'm on the side of money" vs. Nanami leaving a lucrative job to save people out of compassion, and so on.

So it's particularly impressive that, while operating within the shounen genre, the story continues to maintain its respect for this ideological diversity by preserving Mai’s belief in her own worldview to the very end. Simply put, not everyone wants to become powerful even if they may have the potential to. Not everyone wants to live a life of violence, and not everyone wants to be a saviour for others at the direct expense of their own sanity.

It would be perhaps the more optimistic yet potentially oppressive narrative move to demand for Mai's character to undergo a transformation from a character who resists the shounen ideals to one who accepts them. This type of transformation would by no means be inherently negative; I'm definitely not saying that going down this path would have been bad for Mai's character or for the story. But it would succumb to a temptation to move towards a kind of 'sameness' rather than difference in its depiction of ways of acting in the world. I think Mai's ending is all the more striking because it resists this temptation.

Because I think that the more typical - and optimistic - development arc for Mai would have been for her to learn how to be willing to become stronger as a sorcerer and eventually fight alongside Maki.

But instead, Mai never ends up conforming to those dominant values of strength and ambition. Neither is she subjected to the kind of development traditionally favoured by the genre that are along the lines of, 'you just need to believe in yourself and work hard' -- because if we really think about it, often times a lot of feats in shounen are accomplished by sheer willpower and self-conviction. (JJK is not always an exception to that trope, nor is it necessarily a bad thing!). Mai had previously firmly stated her opposing point of view, and this essential attitude never changes even when we perhaps most expect it to.

In this situation, rather than working to improve her technique to create stronger objects without it costing her life, Mai passively accepts that her weakness will require self-sacrifice.

It’s a fatalistic attitude resulting from having never wanted to partake in a life of violence and hardship.

On the one hand, inflexibility and the inability to adapt are not exactly commendable traits; Mai is certainly fixed in her resignation and refusal to work towards her full potential as a sorcerer. On the other hand, to use Nanami's words, being a sorcerer is shit. All the suffering and regret in the story so far has only continued to reaffirm that sentiment. So we also can't fully condemn Mai for rejecting that way of life to the extent that she would rather sacrifice herself than to push forward to have her own "shounen power-up" moment. Because the aftermath of that would be a path likely filled with death, brutality, and suffering.

The wish to live a normal life is a legitimate and valid one. In an ideal world, her clan would not punish her for it. In an ideal world, opposing perspectives, especially ordinarily pacifist ones like Mai's, would be allowed to exist. Mai having to die because she was unable to escape or adapt to the ruthlessness of the jujutsu world exemplifies how cruel that world is. Mai's persistence in her wish for a normal life, and her "failure" as a sorcerer is not her failure at all; her death reflects a failure of the violently rigid jujutsu clan culture.

In this light, it is all the more tragic that Mai's death was entirely preventable, and fated not by the inevitability of actual "fate", but rather entirely by a radically traditionalist clan system.

At the same time, as I mentioned earlier, I find it impressive for Gege to have allowed Mai to hold onto her values. Just as Maki has always stayed true to her dreams of overturning the Zen'in clan by becoming a powerful sorcerer, Mai has always stayed true to her resistance to that dark and difficult path. From a writing perspective, I think it's interestingly respectful to Mai's character in that way. It's also for this reason that I consider this chapter to be a worthy good-bye to Mai, as she is faithful to her own way of being in the world until the end. It may not conform to the demands of the optimistic self-improvement narrative generally preferred by shounen, but it is a valid perspective, and it is never depicted to be 'lesser than' or 'inferior to' the shounen narrative.

I'm always interested in stories in which there is a genuine dialogue of a diversity of voices, each with their own perspectives and viewpoints even as they conflict with each other - or in other words stories that prioritize 'difference' over 'sameness' in ways of being, thinking, and acting. It's not necessarily uncommon - most if not all stories will feature different character motivations within a given cast. But I think JJK does this particularly well in a particularly convincing way, and 149 is further confirmation of this for me.

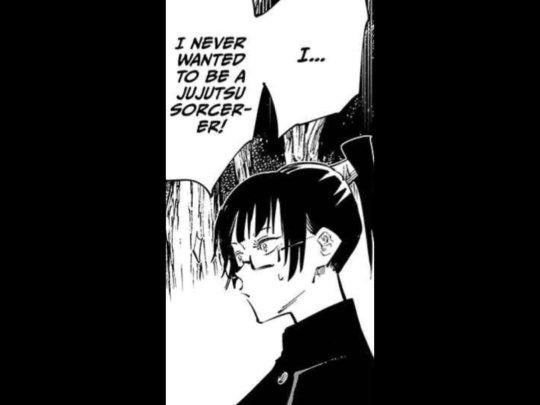

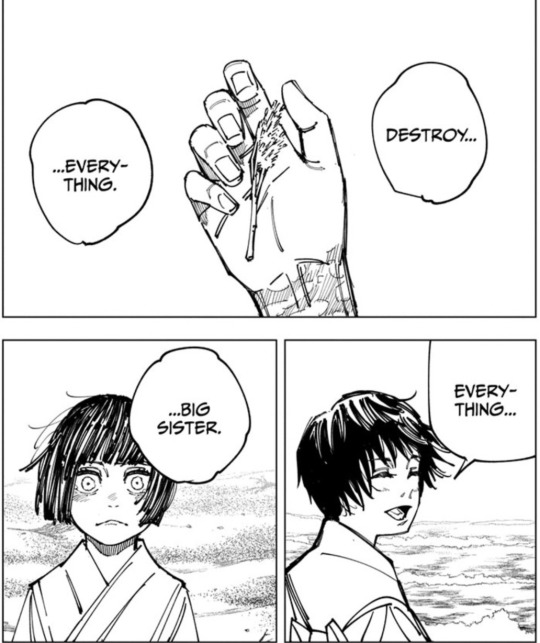

Finally, it is notable that Mai herself seems to acknowledge this sentiment. She may have been unwilling to imagine a stronger future version of herself, which is opposite to the advice Gojou had given Megumi if he wanted to reach his full potential. But she died for the sake of believing in the stronger future version of Maki, and this is how she is victorious even in death. All the way to the end, Mai had her way of viewing and acting in the world in her individual way, and Maki had hers; importantly, Mai ends up encourages this difference. Right after she states that "You are me, and I am you", that sameness is undercut when Mai immediately after points to their contrasting motivations:

Mai ultimately encourages Maki to live in the way that Maki wants to live - to the fullest potential of her power and the fullest potential for her capacity to force change upon a corrupt system. Before, Mai had resented Maki for moving on without her ("why didn't you fall down the hole with me?") - she resented how Maki couldn't be the same as her in how she viewed the world. In her final chapter, Mai conversely acknowledged that she herself could never see the world exactly the same as Maki.

Therein lies the cornerstone of her character development; before, she resented that difference between them for those twofold reasons. In the last moments of her life, she no longer resents Maki for moving on without her; she encourages her to move forward into the future. It is of course undeniably tragic, as it must be a future without Mai. And no amount of power gained from such a loss could ever be consolation for that tragedy.

It is fitting, then, that Mai's final message to Maki is full of despair -- yet it is also not without hope. In the interplay between 'construction' and 'destruction', it is ironic yet poetic that Mai wished for her object-construction technique's final and greatest creation to be used to destroy - indeed, to "destroy everything". There is undoubtedly despair both in that command, and in Maki's drive to destruction when she emerges from that room. But somewhere, somehow, there must also be the hope that that destruction will be in the service of "construction", of creating a better future for others, even if it is too late for it to be a future in which they can live in together.

#jjk meta#jjk 149#mai zenin#maki zenin#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#jjk manga#jjk theory#zenin maki#zenin mai#jjk manga spoilers#jjk spoilers

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I discovered your name metas and am hooked. (Maybe it’s my background in Tolkien fandom - I can’t resist this stuff.) I saw you allude to the character arc in Jiang Cheng/Wanyin’s name. Have you written more fully about him? Or do you plan to? :3

Hello fellow Tolkien fan :D There are already a good handful of name metas for Jiang Wanyin out there, which is why I just casually alluded to Jiang Cheng/Wanyin’s character arc being embedded in his names in one of my metas. But I’ll just throw out my very quick take on his name, while trying to focus more on where my interpretation differs from what’s already been written.

Jiang Cheng (江澄)

Cheng 澄 refers to waters that are clear because they are tranquil. Jiang 江 itself means river. This image of clear, still river waters…isn’t it the opposite of Jiang Cheng’s nature and the course of his life — that is instead so turbulent?

From, his youth he’s pitted against Wei Wuxian by his own mother, feeling inferior to him as well as less deserving of his own father’s love. Then, since the seminal tragedy of the Sunshot campaign, he loses almost everyone he ever loved in his family except Jin Ling. He’s burdened with the duty of bringing the Jiang Sect from the brink to its former glory. Through it all, he’s deceived time and again. The waters are muddied for him so he’s more easily taken advantaged of, or as the saying in Chinese goes, 浑水摸鱼 — muddy the waters so you can capture the fish. The deceptions he’s caught in are born both out of goodwill (such as Wei Wuxian lying to him about his golden core), but also out of ill-intent (such as the circumstances of his sister’s death). Thus, it’s lies that Jiang Cheng lives by for the longest time. It is only at the end of the story that Jiang Cheng gains any sort of clarity about the arc of his life, and the motivations of the people around him. But it feels almost excruciatingly ironic — because by the time the dust has settled the damage has already been done, especially to his relationship with Wei Wuxian… Jiang Cheng can thus feel very poignant as a personal name…

Jiang Wanyin (晚吟)

Then his courtesy name — Jiang Wanyin 晚吟. Both words have multiple meanings. Wan (晚) means late or night. Yin 吟 has more meanings, and I’ll get to them one by one.

The most common interpretation I’ve seen of the courtesy name Wanyin, reads the word yin 吟 the way I think it is more commonly used — to refer to a moan or a groan, typically in pain or regret (as in the phrase shen yin 呻吟). Altogether, it would mean groan of the night, or a late groan. Perhaps at the end of MDZS, Jiang Cheng is full of regret that cannot be truly put into words, only let out in a sound.

Thus, where wan 晚 is interpreted to mean night, the image is of him crying out in a sleepless night.

Alternatively, where wan 晚 means late, it’s almost an indictment of his choices in his life — where by the time he knows to feel regret, to bemoan the decisions he made at critical junctures — it is already too late to salvage things, especially with Wei Wuxian.

But that begs the question — what did the person who gave Jiang Wanyin his courtesy name actually want for him? Surely neither Jiang Fengmian or Yu Ziyuan would give him an inherently tragic name.

This brings us to the other literary meanings of yin 吟, and how wan yin 晚吟 is used in premodern chinese poems.

Yin 吟 can also mean to chant or recite with rhythmic cadence — as in the phrase yin song 吟诵.

Or yin 吟 can be like onomatopoeia for the crying sound made by insects or the wind. Yin feng 吟风 for instance is the cry of the wind.

(One day I might get around to trying to translate a number of ancient chinese poems that use the phrase wan yin in these different ways, if it helps conveys the image of it better).

At any rate, 晚吟 wan yin is found as a phrase or even in the title of poems that are more subdued, wistful, contemplative; or even melancholic and regretful, because of the connotations of nightfall.

My personal theory is thus that the courtesy name Wanyin was given to Jiang Cheng to signify comfort through the vicissitudes of life — the way chanting or reciting a poem, or listening to the steady susurration of cicadas or the wind — can be a soothing accompaniment while one is staying up late. I’d interpret it as a realistic acknowledgement on the part of the giver of this courtesy name that there will definitely be dark times in Jiang Wanyin’s life. But also as their expression of hope that Jiang Wanyin will still manage to find some solace at the end of the day.

This, I believe, would be a kinder read on Jiang Cheng/Wanyin’s situation at the end of the story. He’s lost so much. But at long last his personal name has turned from a cruel irony to a reality — where now at least he has clarity and can move forward to fix things……and his courtesy name suggests he will be able to sustain himself through his newfound sorrows.

But yeah I would definitely be interested to hear other takes on why Wanyin might be given as a courtesy name :3

(PS: For those who can read chinese, this website is v useful for finding poems with particular phrases in premodern chinese poetry. Go knock yourself out looking for all the wan yins and the jiang chengs and how they’re used in different poems :3)

137 notes

·

View notes

Note

oh man i have a Lot of thoughts about the autopsy of jane doe, both positive and critical For Sure, i'd be SO excited to see your analysis of it! definitely keeping an eye out for that 👀

thanks! i'm working on something article-like to talk about the film and i don't know what i want to do with it yet lol but if i don't post it on here i'll definitely link it. it's mainly a discussion of gender in possession/occult films in the same way that carol clover describes in men, women, and chainsaws - that there are dual plot lines in occult films, usually gendered masculine and feminine respectively, where the "main" feminine plot (the actual possession) is actually a way to explore the "real" masculine plot (the emotional conflict of the "man in crisis" protagonist). typically the man in crisis is too masculine, or "closed" emotionally, where the woman is too "open," which is why she acts as the vehicle for the supernatural occurrence as well as the core emotions of the film. the man has to learn how to become more open (though if he becomes too open, like father karras in the exorcist, he has to die by the end - he has to find a happy medium, where he doesn't actually transgress gender expectations too much. clover calls this state the "new masculine," and we might apply the term "toxic masculinity" to the "closed" emotional state). part of the "opening up" feature of the story is that it allows men to be highly emotionally expressive in situations where they otherwise might not be allowed to, which is cathartic for the assumed primary audience of these films (young men). another feature of the genre is white science vs black magic (once you exhaust the scientific "rational" explanations, you have to accept that something magic is happening). the autopsy of jane doe does this even more than the films she discusses when she published the book in 1992 (the exorcist, poltergeist, christine, etc) because the supernaturally influenced young woman who becomes this kind of vehicle is more of an object than a character. she doesn't have a single line of dialogue or even blink for the entire runtime of the movie. the camerawork often pans to her as if to show her reactions to the events of the movie, which seems kind of pointless because it's the same reaction the whole time (none) but it allows the viewer to project anything they want onto her - from personal suffering to cunning and spite.

compare again to the exorcist: is the story actually about regan mcneil? no. but do we care about her? sure (clover says no, but i think we at least feel for her situation lol). and do we get an idea of what she's like as a person? yes. even though her pain and her body are used narratively as a framework for karras' emotional/religious crisis, we at least see her as a person. both she and her mother are expendable to the "real" plot but they're very active in their roles in the "main" plot - our "jane doe" isn't afforded even that level of agency or identity. so. is that inherently sexist? well, no - if there were other women in the film who were part of the "real" plot, i would say that the presence of women with agency and identity demonstrate enough regard for the personhood of women to make the gender of the subject of the autopsy irrelevant. but there are none. of the three important women in the film, we have 1) an almost corpse, 2) an absent (dead) mother, and 3) a one dimensional girlfriend who is killed off for a man's character development/cathartic expression of emotions. all three are just platforms for the men in crisis of this narrative.

and, to my surprise, much of the reception to the film is to embrace it as a feminist story because the witch is misconstrued as a badass, powerful, Strong Female Character girl boss type for getting revenge on the men who wronged her, with absolutely no consideration given to what the movie actually ends up saying about women. and the director has said that he embraces this interpretation, but never intended it. so like. of course you're going to embrace the interpretation that gives you critical acclaim and the moral high ground. but it's so fucking clear that it was never his intention to say anything about feminism, or women in general, or gender at all. so i find it very frustrating that people read the film that way because it's just. objectively wrong.

there's also things i want to say about this idea that clover talks about in a different chapter of the book when she discusses the country/city divide in a lot of horror (especially rape-revenge films) in which the writer intends the audience to identify with the city characters and be against the country characters (think of, like, house of 1000 corpses - there's pretty explicit socioeconomic regional tension between the evil country residents and the travelers from the city) but first, they have to address the real harm that the City (as a whole) has inflicted upon the Country (usually in the forms of environmental and economic destruction) so in order to justify the antagonization the country people are characterized by, their "retaliation" for these wrongs has to be so extreme and misdirected that we identify with the city people by default (if country men feel victimized by the City and react by attacking a city woman who isn't complicit in the crimes of the City in any of the violent, heinous ways horror movies employ, of course we won't sympathize with them). why am i bringing this up? well, clover says this idea is actually borrowed from the western genre, where native americans are the Villains even as white settlers commit genocide - so they characterize them as extremely savage and violent in order to justify violence against them (in fiction and in real life). the idea is to address the suffering of the Other and delegitimize it through extreme negative characterization (often, with both the people from the country and native americans, through negative stereotyping as well as their actions). so i think that shows how this idea is transferred between different genres and whatever group of people the writers want the viewers to be against, and in this movie it’s happening on the axis of gender instead of race, region, or class. obviously the victims of the salem witch trials suffered extreme injustice and physical violence (especially in the film as victim of the ritual the body clearly underwent) BUT by retaliating for the wrongs done to her, apparently (according to the main characters) at random, she's characterized as monstrous and dangerous and spiteful. her revenge is unjustified because it’s not targeted at the people who actually committed violence against her. they say that the ritual created the very thing it was trying to destroy - i.e. an evil witch. she becomes the thing we're supposed to be afraid of, not someone we’re supposed to sympathize with. she’s othered by this framework, not supported by it, so even if she’s afforded some power through her posthumous magical abilities, we the viewer are not supposed to root for her. if the viewer does sympathize with her, it’s in spite of the writing, not because of it. the main characters who we are intended to identify with feel only shallow sympathy for her, if any - even when they realize they’ve been cutting open a living person, they express shock and revulsion, but not regret. in fact, they go back and scalp her and take out her brain. after realizing that she’s alive! we’re intended to see this as an acceptable retaliation against the witch, not an act of extreme cruelty or at the very least a stupid idea lol.

(also - i hate how much of a buzzword salem is in movies like this lol, nothing about her injuries or the story they “read” on her is even remotely similar to what happened in salem, except for the time period. i know they don’t explicitly say oh yeah, she was definitely from salem, but her injuries really aren’t characteristic of american executions of witches at all so i wish they hadn’t muddied the water by trying to point to an actual historical event. especially since i think the connotation of “witch” and the victims of witch trials has taken on a modern projection of feminism that doesn’t really make sense under any scrutiny. anyway)

not to mention the ending: what was the writer intending the audience to get from the ending? that the cycle of violence continues, and the witch’s revenge will move on and repeat the same violence in the next place, wherever she ends up. we’re supposed to feel bad for whoever her next victims will be. but what about her? i think the movie figures her maybe as triumphant, but she’s going to keep being passed around from morgue to morgue, and she’s going to be vivisected again and again, with no way to communicate her pain or her story. the framework of the story doesn’t allow for this ending to be tragic for her, though - clearly the tragedy lies with the father and son, finally having opened up to one another, unfortunately too late, and dying early, unjust deaths at the hands of this unknowable malignant entity. it doesn’t do justice to her (or the girlfriend, who seems to be nothing but collateral damage in all of this - in the ending sequence, when the police finds the carnage, it only shows them finding the bodies of the men. the girlfriend is as irrelevant to the conclusion as she is to the rest of the plot).

but does this mean the autopsy of jane doe is a “bad” movie? i guess it depends on your perspective. ultimately, it’s one of those questions that i find myself asking when faced with certain kinds of stories that inevitably crop up often in our media: how much can we excuse a story for upholding regressive social norms (even unintentionally) before we have to discount the whole work? i don’t think the autopsy of jane doe warrants complete rejection for being “problematic” but i think the critical acclaim based on the idea that it’s a feminist film should be rejected. i still consider it a very interesting concept with strong acting and a lot of visual appeal, and it’s a very good piece of atmospheric horror. it’s does get a bit boring at certain points, but the core of the film is solid. it’s also not trying to be sexist, arguably it’s not overtly sexist at all, it’s just very very androcentric at the expense of its female characters, and i’m genuinely shocked that anyone would call it feminist. so sure, let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water, but let’s also be critical about how it’s using women as the stage for men’s emotional conflict

also re: my description of this little project as “a film isn’t feminist just because there’s a woman’s name in the title” - i actually don’t want to skim over the fact that “jane doe” isn’t a real name. of the three women in the film, only one has a real name; the other two are referred to by names given to them by men. i’ll conclude on this note because i want to emphasize the lack of even very basic ways of recognizing individual identity afforded to women in this film. so yeah! the end! thanks for your consideration if you read this far!

#the autopsy of jane doe#men women and chainsaws#horror#also to be clear i'm not saying that the exorcist is somehow more feminist because. it's not. i'm just using it as a frame of reference#you'd think a film from 2016 would escape the ways gender is constructed in one from 1973 but that's not really the case#i actually rewatched the end of the movie to make sure that what i said about the girlfriend's body not being found at the end was accurate#and yeah! it is! the intended audience-identified character shifts to the sheriff who - that's right! - is also a man#the camerawork is: shot of the dead son / shot of the sheriff looking sad / shot of the dead father / shot of the sheriff looking sad /#shot of jane doe / shot of the sheriff looking upset angry and suspicious#which is how we're supposed to feel about the conclusion for each character#the girlfriend is notably absent in this sequence#anyway! this is less about me condemning this movie as sexist and more about looking at how women in occult horror#continue to be relegated to secondary plot lines at best or to set dressing for the primary plot line at worst#and what that says about identification of viewers with certain characters and why writers have written the story that way#i think the reception of the film as Feminist might actually point to a shift in identification - but to still be able to enjoy the movie#while identifying with a female character you need to change the narrative that's actually presented to you#hence the rampant impulse to misinterpret the intention of the filmmakers#we do want it to be feminist! the audience doesn't identify with the 'default' anymore automatically#i think that's actually a pretty positive development at least in viewership - if only filmmakers would catch up lol#oh and i only very briefly touched on this here but the white science vs black magic theme is pretty clearly reflected in this film also

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hidden in Plain Sight

Pairing: Dean Winchester/Jeremy Bradshaw

Tags: Early seasons Dean, pre-podcast Professor Bradshaw, denial, unresolved sexual tension, bickering, smut, gratuitous owl references, case fic

Summary: It's the fall of 2006, and a string of grisly deaths linked to local lore brings Sam and Dean to the village of Bridgewater. There, Dean finds himself working closely with the frustrating and unexpectedly compelling Professor Bradshaw.

---

Dean feels about as comfortable in old colleges as he does in churches. There’s the same sense of exclusivity, that same reverence of things Dean has spent his life stuck on wrong side of. This campus even feels a little like a church, with its old architecture and sprawling ruby ivy and slit windows like narrowed eyes. His footfalls echo heavily along the cold stone corridor, making him feel uncomfortably aware of his own existence.

The door he’s looking for is old and made of oak, nestled in an alcove near the staircase, with a small plaque on it that reads Professor J Bradshaw.

Dean pauses for a moment, then knocks abruptly, suddenly noticing his knuckles are still smudged with earth. From within, a muffled voice instructs him to enter, and he does so, wiping his hand surreptitiously against the side of his leather jacket.

The first thing that hits him is the sheer volume of books in the room; they clutter every available surface, piled high in front of the big bay window like a strange line of defense. There are stacks of loose papers everywhere too, haphazard but clearly organized, some held in place by empty coffee mugs or odd-looking artefacts. The air is bright and warm, like this room catches the sun when it’s slow and mellow in the afternoons.

The second thing that hits him is the man sitting at the desk.

He doesn’t look up at Dean’s entrance, continuing to scribble away in a leather-bound notebook with intent dexterity, seemingly utterly lost in his own thoughts. He’s not what Dean expected; surprisingly young, maybe approaching forty, with a sharp jaw and tousled hair that just brushes his broad shoulders. When Dean clears his throat awkwardly, the man finally looks up with striking blue eyes that immediately pin Dean in place.

“Yes?” his voice is inquiring and several octaves deeper than Dean would have imagined, low and gravelly. He sets down his pen, looking at Dean with piercing focus.

“Uh – hey. Professor Bradshaw?” Dean feels distinctly self-conscious.

“Who wants to know?” the man closes his notebook with a snap and stands with surprisingly fluid ease, eyes still intent on Dean as though he’s cataloguing him.

He’s wearing a faded navy-blue sweater with the sleeves rolled up, slightly crumpled shirt tails poking out at the hem, just visible.

Drawing on years of sizing people up, Dean guesses that the guy probably has no one to go home to at night. If he goes home much at all, that is; the office has a distinctly lived-in look. It’s strangely reminiscent of the makeshift home feel of the impala’s interior.

“Um – Dean. Dean Collins,” Dean answers hastily, suddenly realizing he’s spent a little too long looking. “I’m uh – a student in one of your classes,” he lies the best way he knows how: with a charming smile. “I was wondering if you’ve got a moment? I was hoping to ask you a couple of questions about your work.”

“Come in, please,” Professor Bradshaw sits back down behind his desk, and gestures for Dean to close the door. “Take a seat.”

“Thanks,” Dean shuts the door and awkwardly removes three hardback books and a small, slightly drooping fern from the only available seat in front of Professor Bradshaw’s desk.

“Sorry – let me –” Professor Bradshaw leans over the desk to relieve Dean of the books and the plant. Close up, Dean can see faint lines softening the corners of his vivid eyes, and when he breathes in, he catches a hint of peppermint and the musk of warm skin, strangely compelling. Their hands brush for a moment as Professor Bradshaw takes the items, and Dean flinches, jerking away and planting himself firmly on the chair.

“So – Dean, yes?” Professor Bradshaw settles back into his seat. He’s still looking intently at Dean, gaze startlingly blue.

Wordlessly, Dean nods. He doesn’t know why he can feel the heat creeping up his cheeks.

“You’re not in any of my classes, Dean,” Professor Bradshaw says, with a slight edge to his voice. He reaches for a half-drunk mug of tea on his desk, expression skeptical.

Dean feels his stomach drop. “Uh, yeah – I’m new, just transferred a couple weeks back,” he bluffs quickly, but it sounds weak even to his own ears. He feels strangely flustered, visible.

“No, I don’t think so,” Professor Bradshaw says, flatly. “I believe I would have noticed,” he adds, wryly, with a kind of impatient warmth in his expression that makes Dean’s cheeks flare with heat all over again. Professor Bradshaw merely swallows a mouthful of tea and sets the mug back down, still looking at Dean. “So. Who are you?”

“Alright,” Dean puts his hands up in mock-surrender, smiling wide even though he feels stupidly on edge, knocked off course. “You got me. I’m – uh – a journalist. My boss has me writing a piece on local legends, and I was hoping to pick your brains. Heard you’re the expert on all that stuff around here, and thought I might be in with a better chance of talking to you as a student instead of some annoying reporter.”

“I see,” Professor Bradshaw leans back in his chair, contemplative. A shaft of sunlight filters through the bay window behind him, illuminating a hint of tawny in his dark, untidy hair. Dust motes hang everywhere like suspended snow. “Well, luckily for you, Dean, I find that my students can be just as annoying as reporters. And I still talk to them on a daily basis.”

Dean grins a little awkwardly, “Yeah?”

“Of course, I do get paid to do that,” Professor Bradshaw adds, dryly. “But perhaps I do them a disservice. Some of them are really quite inspiring.” He pauses, raising his mug to his lips. It has an owl on it, Dean notices absently. An overly fluffy one, with a slightly threatening glare. “I daresay I can spare five minutes. What is it that I can do for you, Dean?”

“Uh, so you study the supernatural, right?” Dean asks, clumsily. His hands are sweating where they’re shoved in the pockets of his jacket. “Ghosts and demons and all that shit?”

“I study the lore and mythology of supernatural beings, and why it’s important to humans to create such stories,” Professor Bradshaw clarifies, shortly.

“Right, got it,” Dean agrees, hastily. “But you’d know a bit about the Bridgewater coven?”

“I am familiar with the legends, yes,” Professor Bradshaw replies, reaching for his mug again. There’s an ink stain on the side of his index finger, smudged deep blue. Dean fleetingly wonders if it would rub off easily if he touched it, if it would leave a ghostly imprint on his own skin.

“Yeah – uh – so there’s been quite a lot of interest in the coven recently,” Dean blusters, annoyed with himself for how stupidly flustered he feels, “You know, since those bodies were found last week? At the burial site in Bridgewater Forest that’s associated with the legend? Yeah. Well, anyway, I was – hoping you might be able to tell me a little more about the legend of the coven.”

“I don’t see what the recent tragedies could possibly have to do with the legend,” Professor Bradshaw narrows his eyes skeptically.

“Right – yeah – nothing, I’m sure,” Dean lies hastily, “But the location of the crimes has definitely raised awareness about the existence of the legend, and that’s what we really want to provide for our readers.”

“Well, certainly, I can tell you the history,” Professor Bradshaw replies, briskly, “In fact, I teach an undergrad course on witchcraft in history and my lecture this Wednesday actually covers the legend of the coven. If you want a more detailed, nuanced version, you’re more than welcome to come along then – it’s at 11am in the Milton building. But I’m happy to give you the short version now, if that would be helpful?”

“Thanks – yeah, that’d be great,” Dean says, gratefully. “On a bit of a tight schedule today.”

“Well, the local legend about the Bridgewater coven has existed for almost two hundred years,” Professor Bradshaw starts, and immediately Dean can picture him talking in front of a lecture theatre full of kids. He’s a natural, something inherently captivating about the way he speaks. “In the 1800s, this village was an important site of religious pilgrimage. However, according to the legend, the village was also home to a small coven lead by a witch named Iris. Iris’s coven was said to have lived in secrecy in the forest on the outskirts of Bridgewater for years, and not to have troubled the village people. However, by 1816, the legend claims the coven had become very hostile, specifically towards the church. There were fears the coven had begun indoctrinating – or bewitching – members of the congregation.”

Professor Bradshaw pauses, swallowing another mouthful of tea. The muscles in his throat work, drawing Dean’s attention to the way his pale blue shirt isn’t buttoned up properly. He’s filled with the sudden, inexplicable urge to button it up correctly.

“More and more people started disappearing in connection with the coven,” Professor Bradshaw continues, setting his mug back down on the desk, and Dean jerks his gaze guiltily away from the line of his throat, clenching his hands into fists inside the pockets of his leather jacket. “The rapidly diminishing congregation lived in terror. The remaining members of the church all turned against each other. Then, at the height of local hysteria, Iris is said to have murdered Blanche, the minister’s daughter, in what is portrayed in the lore as some kind of statement of the coven’s power over the church.”

“Bet that didn’t go down too well,” Dean remarks, sardonically.

“Quite,” Professor Bradshaw catches Dean’s eye, an amused smile tugging at the corners of his mouth. “Anyway, according to the legend, the tragedy of Blanche’s death united the warring members of the congregation. They captured Iris and entombed her alive, using her own magic against her to keep her trapped. Iris’s death broke the spell on the members of the congregation who’d been indoctrinated against their will, and peace was restored to the village. The few remaining members of the original coven fled and were never seen again.”

“Wow,” Dean raises his eyebrows, “Very love-thy-neighbor.”

Professor Bradshaw snorts, “Yes. Religious leaders in the 1800s were renowned for sitting down and resolving their problems through compassionate discussion,” he remarks, dryly.

“Okay, but what about the other versions of the legend?” Dean asks, trying to remember the things Sam had told him to ask about, but drawing a total blank. His brain feels weirdly scrambled. It’s hard to remember what happened before walking into Professor Bradshaw’s office. “The other stories about the coven I’ve come across so far all seem pretty different.”

Professor Bradshaw frowns slightly. “It’s true, there are many conflicting accounts. Which is often the case with legends, being human constructions of the past,” he regards Dean slightly disapprovingly over the rim of his owl mug, a kind of skeptical stubbornness in the set of his mouth. “It’s not about knowing which ‘to believe’ – it’s about looking at why historically people have favored one version over the other and what that tells us about them.”

“Right, yeah, but aren’t legends often based on fact?” Dean pushes.

Professor Bradshaw pauses, contemplatively, “Yes. That’s certainly true in some cases.”

“Do you think it’s the case in this one?”

“Possibly,” Professor Bradshaw replies, haltingly. His expression is serious and he hesitates for a moment before elaborating; “In fact, I’m currently writing a paper about the historical figures who feature in the legend of the Bridgewater coven.”

“Yeah? Which ones?” Dean presses. He’s used to having to fake interest to get information out of people like Professor Bradshaw, but for once, he finds he’s genuinely interested. There’s something compelling about Professor Bradshaw’s evidently obsessive quest for obscure answers, something that resonates with all too much familiarity.

“Iris, predominantly,” Professor Bradshaw replies. “I’m very interested in the historical reasons women were condemned as witches. Often, it’s as simple as jilted male lovers using accusations of witchcraft as a means of revenge, or the women using herbal remedies that threatened contemporary male ideas of medicine and the body. Sometimes it’s to do with female homosexuality and society’s unacceptance of same sex relationships or women as sexual beings. Of course, it wasn’t uncommon for gay men to be condemned for witchcraft either. But statistically, more homosexual women died as a result of such accusations.”

“Uh – right –” Dean swallows, looking away. His hands are sweating again, and he wipes them surreptitiously on the insides of his pockets. Clearing his throat, he changes the subject, suddenly remembering the other thing Sam had told him to ask Professor Bradshaw about, “What about the runes?”

“Ah yes, the runes on Iris’s supposed tomb,” Professor Bradshaw’s gaze is suddenly inscrutable in a way that makes Dean’s heart thud uncomfortably in his chest. It sweeps over Dean, lingering and unnervingly blue for a moment, before he continues, “Very interesting. I’ve been studying them a great deal as part of my research. The true nature of them has always remained a mystery, and any attempts to discern their meaning haven’t fitted with the legend at all. I believe they may be key to understanding the history behind the creation of the legend. But,” he smiles, wryly, “It’s not an easy task. They’re unlike any runes I’ve come across anywhere else before.”

“Can I see?” Dean asks, partly out of interest, and partly for some way of distracting himself from the way his heart is still thumping uncomfortably fast.

“You’d have to visit the forest burial site to see them in person, but I do have a couple of sketches of the lines I’m working on at the moment,” Professor Bradshaw gets to his feet and crosses to the cabinet by the window, pulling the top drawer open.

The fall chestnut trees outside smolder amber behind his silhouette, midday sunshine pale gold and still where it filters through the window. Time seems strangely irrelevant. Dean watches as Professor Bradshaw flicks through a green binder, fingers quick and dexterous, skilled and uncalloused in a way Dean’s have never had the chance to be.

Dean swallows and looks away, ignoring the thud of his heart as he stares around at the rest of the room. He clocks a bunch of compendiums of mythology on the bookcase nearest him, and two other eccentric and slightly neglected looking plants. There’s a thick plaid rug on the couch in the corner, not quite concealing a plate of half-eaten toast. On the windowsill, there’s a little tin mug with a toothbrush in it that makes Dean wonder again just how often Professor Bradshaw goes home at all. He finds himself wondering whether Professor Bradshaw has always had nothing but an empty house to return to, or whether that’s a more recent development. He’s definitely old enough to be going through a divorce. The thought sits uncomfortably in Dean’s chest for reasons he doesn’t particularly want to identify.

“Here we are.” Professor Bradshaw’s gravelly voice, suddenly much closer, makes Dean jump. He glances around to find Professor Bradshaw standing beside him, holding out a sheet of paper. The smell of warm skin and peppermint catches Dean off guard, stronger this time, and still strangely compelling.

“Uh – thanks,” Dean says awkwardly, taking the proffered page. He feels Professor Bradshaw’s fingers brush against his fleetingly, warm and ink-stained.

Dean swallows, forcing himself to focus on the page in front of him even though his cheeks are hot with something he doesn’t want to think about. The sketches are good, a few strange vaguely Norse reminiscent symbols drawn hastily with accompanying, scrawled notes in the margins. There’s something about the runes that niggles at Dean’s brain, familiar and unfamiliar all at once, like something he’s known his whole life but can’t put his finger on.

“These are interesting,” Dean he frowns, tracing his finger along the two last symbols.

When he glances up, he finds Professor Bradshaw looking at him intently, blue eyes inscrutable. “Yes,” he says, leaning back against the desk and folding his arms across his chest. “Those are the ones which struck me too,” he’s speaking a little quieter, low voice distracting Dean from why the runes are so familiar. He hopes he can remember them, that Sam will be able to place what he can’t about them.

“So, uh, this tomb. The one with the runes on it – that’s definitely where that guy’s body was found last week? It wasn’t just nearby or something?” Dean forces himself to ask, ignoring the way his heart is suddenly thumping again. “And the girl found the week before – she was directly linked to the burial site too?”

Professor Bradshaw clears his throat, unfolding his arms. “I believe so, yes.”

“And that doesn’t seem – I don’t know – a little strange, to you?”

“Human beings committing violent acts against each other is generally something I find a little strange,” Professor Bradshaw replies, in clipped tones. “But beyond that – no. Now –” he breaks off, glancing at his watch. “I’m afraid I have a seminar to deliver in ten minutes,” he confesses, and there’s something unfinished about the way he says it, something almost reluctant. Like he half wants to stay here talking with Dean.

“No problem,” Dean stands, and takes a last glance at the sketches before handing them back, trying to commit them to memory. “Thanks, Professor.”

Their eyes meet as Professor Bradshaw accepts the page, and the room suddenly feels very airless, a pause suspended between them. Neither of them moves away.

This close, Dean can see miniscule flecks of grey like tiny stars lost in blue of Professor Bradshaw’s eyes, the way that his full lips are slightly chapped, like maybe he worries them between his teeth when he’s thinking. They’re soft pink and warm-looking, and Dean wonders fleetingly if they taste like peppermint tea.

“It was nice meeting you, Dean,” Professor Bradshaw says, gently, and his eyes are so blue.

“Uh – yeah – you too. Thanks. I’d – uh – I’d better get going,” Dean stammers, shoving his hands deep in his pockets and cursing the way his cheeks are suddenly flaming with heat. His thoughts churn unsteadily; he ignores them the way he’s learnt to.

Still feeling strangely wound-up, he nods awkwardly at Professor Bradshaw and turns reluctantly towards the door.

“Wait a moment, Dean –” Professor Bradshaw’s voice halts Dean in his tracks as he reaches the door, and Dean turns expectantly, heat thumping a little painfully.

“Yeah?”

“Here – you’re welcome to borrow a couple of books on local history,” Professor Bradshaw is pulling a couple of books down from the overflowing cabinet by the window. “They should have a bit more about the legend of the coven that you might find interesting. Divergences of the legend and so forth. I’ll need them back by Thursday morning as I’m teaching a class on them in the afternoon, but you’re welcome to borrow them until then if they’d be helpful.”

“You sure?” Dean takes the proffered books awkwardly, and swallows the strange disappointment sinks in him like a stone as Professor Bradshaw steps back again. “Thanks.”

“As I said, I’m also giving a lecture on Wednesday where I’ll be examining the history behind the legend of the coven. I meant what I said - you’d be more than welcome to attend,” Professor Bradshaw says, sincerely. His eyes are intent, and there’s a hint of something almost like hopefulness hidden in the depths of his gravelly voice. Working on long ingrained instinct, Dean chooses to ignore it.

“Thanks, I’ll – I’ll see what my schedule’s like,” Dean replies, haltingly.

“Of course,” Professor Bradshaw agrees. He turns back to his desk.

“Can I ask –” Dean pauses, watching Professor Bradshaw stuff another notebook and a stack of handouts into his briefcase. “You said you’re writing a paper about the runes at the forest burial site– do you go to there much?”

Professor Bradshaw glances up, distractedly. “Yes, I spend time there every week.”

“So you haven’t noticed anything – I don’t know – anything unusual when you’ve been there recently?” Dean ventures.

“Unusual how?” Professor Bradshaw closes his briefcase with a snap and looks up at Dean properly, eyes narrowed with sudden skepticism. It’s stronger than the hints Dean has caught at other points during their conversation, sharp and blue, a world away from the observant warmth of a few moments ago.

“I dunno – odd noises, sudden drops in temperature, shadows –”

“Just what are you asking me?” Professor Bradshaw demands, voice clipped and defensive.

“Have you seen anything like that?” Dean presses, stubbornly. Irritation prickles his skin.

“No, I haven’t,” Professor Bradshaw says, bluntly. “And you know why? Because yes, I study the supernatural – but it’s not real, Dean. I don’t know what kind of sensational article you’re writing about local lore, but I can assure you, lore is all it is.” He winds a striped scarf haphazardly around his neck, and grabs his briefcase off the desk. “Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a class to teach.”

-

Sam is eating some gross looking granola yoghurt pot with a plastic spoon when Dean eventually clambers back into the car, feeling distinctly frustrated.

“You took your time,” he remarks idly, raising an eyebrow as Dean adjusts the mirror with an unnecessary amount of force and turns on the ignition.

“Goddamn waste of time was what it was,” Dean mutters mutinously, pulling out of the space and then immediately being forced to hit the brakes when a cluster of students cross the parking lot in front of him. He grinds his teeth and resists the urge to honk the horn. “Thought I was getting somewhere but he completely shut down the minute I asked him if he’d noticed anything weird at the burial site.”

“Suspicious?” Sam frowns, through a mouthful of granola.

“No, don’t think so. Just really damn touchy,” Dean drums his fingers impatiently against the wheel as he waits for the students to move, “And a bit of an asshole. I dunno, suppose working in his field he’s probably used to people thinking he’s just some lunatic who believes in the supernatural.”

“And does he?”

Dean snorts. “No way. He’s got a real bee in his bonnet about it. You’d think someone who’s spent the last twenty years with their head buried in books about ghosts and covens and demonic possession might be a little more open to the idea,” he shrugs, and gives in to the temptation to lean on the horn, reveling in the brief satisfaction of making the students jump and scurry out of the way, “But no. The guy’s absolutely blind to it all, and could rival you on stubbornness.”

Sam purses his mouth in annoyance, but doesn’t rise to the bait. “Get anything useful at all?”

“He did lend me a couple books,” Dean admits, nodding in the direction of the backseat. “Have to take them back on Thursday morning, though. He needs them for some class.”

“He leant you his books?” Sam raises his eyebrows.

“Yeah,” Dean shrugs, skin prickling in annoyance, “What of it?”

“Dunno, that’s just,” Sam swallows a mouthful of yoghurt, “Pretty trusting. Academics usually treat their books as if they’re their first borns.”

“Don’t mess them up when you read them, then,” Dean says, dismissively, as they pull out onto the main street. “You find out anything useful about the victims?”

“Not really,” Sam leans back in his seat with a sigh, “Both from middle class, religious families. Seem to have been pretty well liked by people. Hard to establish any link more than that. The wife of the guy that was killed last week seemed a bit cagey, though,” he shrugs, “Might be worth a second visit to see if she’s holding out on us about something.”

“Right,” Dean drums his fingers impatiently against the wheel as they wait for a light to change. It’s starting to drizzle, tiny flecks of grey hitting the windshield. “Are we still definitely thinking ghost?”

“Seems like it,” Sam affirms, “The way the victims died definitely points to a vengeful spirit. But the place they were killed – connected to the burial site associated with the coven? I don’t know, I was thinking maybe it’s no ordinary ghost. Maybe it’s the vengeful spirit of a witch, and that’s why it’s so powerful?”

“Hm,” Dean mulls it over, flicking the windscreen wipers on as they continue to wait. They squeak slightly, repetitive and familiar. “You could be onto something there.”

“Yeah?”

“Professor Bradshaw was telling me about the local legend of the coven. Apparently, its leader was entombed alive by a bunch of angry churchgoers,” Dean steps on the accelerator as the light finally changes, and the rain-slicked village slides past in a blur. “That’s got to be some pretty good vengeful spirit material right there. And you said the victims were both religious, right? Can’t be a coincidence.”

“Why now, though?” Sam frowns. “It’s been what – two hundred years? There must have been plenty of churchgoers who walked by the burial site before now.”

“Dunno,” Dean shrugs, staring out at the rainy smudge of fall colors. The chestnuts trees lining the street are the same smoldering hue of amber as the one outside Professor Bradshaw’s window.

They drive in silence for a few moments, wipers squeaking.

“Okay,” Sam says, at length, “So I’m thinking – we go check into a motel, get through as much of these books from your professor as we can while we wait for the rain to stop, and then check out the burial site later this afternoon before it gets dark?” Sam asks, chucking his plastic spoon in the empty yoghurt container.

“He’s not ‘my professor’,” Dean says defensively, and suddenly has to step a little too hard on the breaks to avoid running a red light.

“Alright,” Sam says, slowly. “Okay.”

“Anyway, yeah,” Dean blusters, hastily, ignoring the weight of Sam’s gaze on the side of his face, “Works for me. But first,” he flicks on the indicator and pulls into a space near a little line of local shops. “Food. Not that yoghurty shit you’ve been eating. Real food.”

-

The forest is steeped in quiet in the way all ancient places are, fall singing the leaves on the gnarled branches that claw their way towards the fading gold of the late afternoon sun. Dean breathes in the wet, cloying smell of moss and follows Sam’s careful path through the trees. There’s a chill in the air, but the handle of Dean’s blade is hot in the palm of his hand.

“How much further to this place?” he hisses at Sam’s back, swatting a frond of bracken out of his face and casting his gaze edgily through the twisting branches and burnt amber.

“Nearly there, according to –” Sam stops so abruptly that Dean nearly collides with him, throwing out a cautionary arm.

“What?” Dean whispers urgently, instantly drawing his blade. His heart is racing now, whole body tense, coiled, ready to attack. His gaze flickers rapidly through the mess of branches and he stands on his tiptoes, trying to see past Sam’s stupidly large frame. “Sammy,” he hisses, impatiently, when Sam doesn’t immediately answer, “What is it?”

“There’s something there,” Sam breathes, almost inaudible. His posture is still, alert. Dean can see Sam’s hold on the gun in his back pocket tighten.

“What kind of something?” Dean whispers, craning his neck to try and see. The light seems somehow dimmer already, the fading sun sliding further towards the ground. When he breathes in, the smell of wet leaves is stronger, now that they’re in the heart of the forest. His heart is thrumming so fast but everything else feels suspended in time, unnaturally still.

“I think it’s a person,” Sam murmurs, and somewhere close, Dean hears the brittle rustle of dead leaves, loud and unnerving in the wooded quiet. He watches the quickened rise and fall of Sam’s shoulders as his breathing suddenly sharpens. “They’re holding something. They – shit, Dean, they’re coming this way.”

Dean reacts immediately and on nearly twenty years of protective instinct; he shoves Sam out of the way and stumbles out into the clearing, blade brandished in front of him.

---

#did i really just create a new ship tag on ao3 just because i couldn't get the idea of early seasons dean and pre-podcast jeremy meeting?#yes#yes i did#feedback truly makes my day <3#crossposting from ao3#bridgewater#bridgewater podcast#supernatural#dean winchester#jeremy bradshaw#dean x jeremy#spn fanfic#dean fanfic#my stuff#my posts: fanfic

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Allegory, Imperfection, and Inadvertent Subversion: A small essay about Akimi Yoshida’s Banana Fish and Salinger’s “A Perfect Day For Bananafish”.

In the story of Banana Fish, Yoshida references Salinger’s short story “A Perfect Day For Bananafish” (which henceforth shall be addressed as “Perfect Day” simply for ease of reading) several different ways, both in-universe and out. It is exceedingly evident that the character of Ash Lynx is heavily based on Seymour Glass, and one might surmise that Banana Fish is an allegorical retelling of “Perfect Day”, especially given that in the original story, Ash Lynx dies of what is arguably a “passive suicide” – that is, when faced with an injury that isn’t immediately fatal, he chooses to bleed out rather than seek help, which when framed as a suicide, parallels the much more violent and sudden suicide of Seymour Glass.

However, this surface-level allegorical reading ignores a very important variable in the story of Banana Fish, namely the counterpart to Ash’s Seymour: Eiji’s Sybil. While Ash and Seymour share many similarities (both are traumatized, troubled geniuses with partly-Irish roots who grew up in New York City), the similarities between Eiji and Sybil are very few. Eiji does symbolize a world of innocence to contrast with Ash’s world of horrors, but unlike Sybil, Eiji is an adult with agency of his own, and though he retains some of Sybil’s childlike innocence and is able to connect deeply with Ash as a result of it, Eiji’s agency and decisions ultimately change the narrative and its meaning.