#any form of oppression he faces is not the center of his narrative its his obsession with Alina

Text

YA protagonist will be like "I know your trying to dismantle an oppressive system but you're being mean about it, so im going to stop you! And patch it out later... maybe..."

#shadow and bone#alina starvok#shadow and bone mal#the darkling#shadow and bone darkling#malina#darklina#ya#ya authors#somebody called Alina an insert for a teen girls to live out their rebel phase#and yeah#it also why Darkling is so boring#any form of oppression he faces is not the center of his narrative its his obsession with Alina#which makes everything he fights for feel so hollow#but that is by design#if you treat revolution as salad dressing then you dont have to adress or do any radical changes to the status quo#just as Lindsay Ellis pointed out in Les mis#not the hunger games tho#that shit should have been the blueprint#an anti the great one man theory that showcases that movements are made of community not ONE great person who leads it all#katniss is a manufactured savior and i absolutely love it#cant believe i wrote this series off as mindless dystopia blame Divergent for that#six of crows#anti alina starkov

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

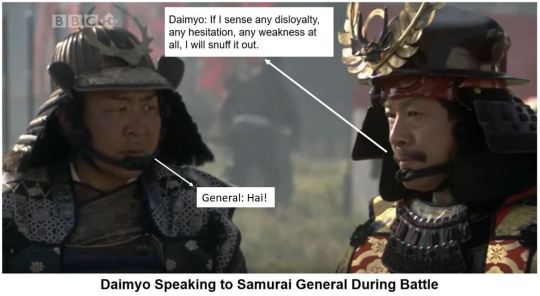

The East Asian Origins of the Fire Nation and Its Villains

Introduction

Over the years, many volumes of fandom blood have been spilled from discussions concerning the Fire Nation’s main villains, Ozai and Azula. Paralleling this have been arguments over their relationships with Zuko, Iroh, Ursa, Mai, Ty Lee, with each other, even with themselves. Since Ozai and Azula are the figureheads of the Fire Nation that Zuko must peacefully restore the honor of, it is worthwhile understanding why people “like them” are considered proper leaders of the current Fire Nation.

Most of these discussions have sought to create “theories” that explain these characters as exclusively combinations of mental illness, personality disorders and various emotional traumas.

A couple examples of these discussions are the essays “Azula, the Embodiment of Jealousy and Neglect,” and “Three Pillars Theory of Azula.” These two essays are just examples, but they capture the widespread strategy the fandom has employed in trying to understand the motivations and goals of Ozai and Azula and their various relationships with the other characters. In addition, the shouting matches between Azula “fans” and “haters” also illustrates these discussions. Since the franchise has yielded so few hard answers, these importance of these discussions has not waned.

What these discussions focus on, as represented by those essays, are the characters’ apparent emotional problems, theoretical moral compasses and perceived inadequacies in the eyes of their families. Typically, the “lens” these discussions view these villains through is one that tries to relate them to present day spousal and domestic abuse narratives, namely as being both “abuser” and “victim” in a cycle of abuse that can be related to the modern, real world.

What these conversations do not provide are adequate explanations for how the historical, political, military and cultural aspects of the Fire Nation molded these military leaders. You would think that people with “Lord” and “Princess” in their names, who train daily for warfare and hand-to-hand combat, would make their responsibilities take center stage in their lives.

While there is a place for “nitty gritty” psychological examinations for understanding certain behaviors, trying to depict the Fire Nation villains as purely allegories of modern day domestic abusers, empathy deficient bullies and people afflicted by personality disorders eliminates Avatar’s most unique and defining characteristic: its East Asian origins.

You don’t need beautiful animation, martial arts-styled bending and immersion in a fantasy world to explain how families in the modern era can hurt their children for petty reasons. We have that in our own lives. We have friends and families who have experienced that. It can be addressed in any other setting. It can be addressed in Avatar but it doesn’t need Avatar to address it.

What we don’t experience in our modern lives is ancient China 2000 years ago, or feudal Japan after the takeover of the Tokugawa Shogun, or religious monks living in their temples in the mountains untouched by the modern world, and so on.

The setting of Avatar is one of both beauty and relative detachment from the real (and modern) world, but it is one that is based on a period of history and human civilization that most of Avatar’s audience (North America and Europe) have little exposure to. If the characters’ motivations are too detached from the fictional world in which they live (i.e. by ignoring the historical, political, military and cultural context), then you begin to lose the world’s depth. At the same time, if their motivations are too connected to the present world, then all Avatar is is a visual motif of ancient East Asia.

By seeking to explain the Fire Nation villains as embodiments of modern psychology’s understanding of “bad” people, you erase the opportunity to apply East Asia’s very real history of warfare, monarchical domination and oppressive cultures to a fictional world that is trying to say something about that warfare, monarchical domination and oppressive cultures. Note that the show did in fact achieve this with the Dai Lee’s corruption and manipulation of the Earth King; it depicted loosely the very real occurrence of Chinese Emperors being “kept in the dark” by their advisors so as not to interfere with the “real” governing of the states.

If your goal is to view Avatar purely as an allegory for modern dysfunctional relationships and domestic abuse, you lose Avatar’s uniqueness as a fictional dive into an East Asian-inspired world, especially one that is ravaged by warfare and feudalism.

In this article, I describe an alternative model for understanding the Fire Nation’s culture and history, and how its politics and military molded its heroes and villains.

What We Know and Might Know

In order to fill the gaps in our knowledge of the Fire Nation, we first have to understand what is both known about the Fire Nation and what can be reasonably presumed about it.

First, what do we know about the Fire Nation?

1. The Fire Nation is an archipelago with a history spanning thousands of years.

2. The Fire Nation was originally the “Fire Islands” and was not initially governed by a central power.

3. The Fire Islands had a unified cultural and religious authority in the form of the “Fire Sages”.

4. Eventually, the Fire Islands were unified by a single power—the “Imperial Government”—and afterward became known as the “Fire Nation”.

5. The Imperial Government is headed by a supreme ruler: the “Fire Lord”.

6. The Fire Lord is a hereditary monarch whose family is considered the “Royal Family”, both of which are separate entities from the Fire Sages.

7. The Fire Sages remain a distinct entity from the Imperial Government.

8. Both the Fire Lord and Royal Family are military and administrative rulers.

9. The Fire Lord and their Royal Family are not sacred and everlasting; their power can be “challenged” by rival leaders.

10. Fire Lords are expected to “show their worth” and be competent fighters in their own right; prowess in military arts and control of subordinates are valued traits.

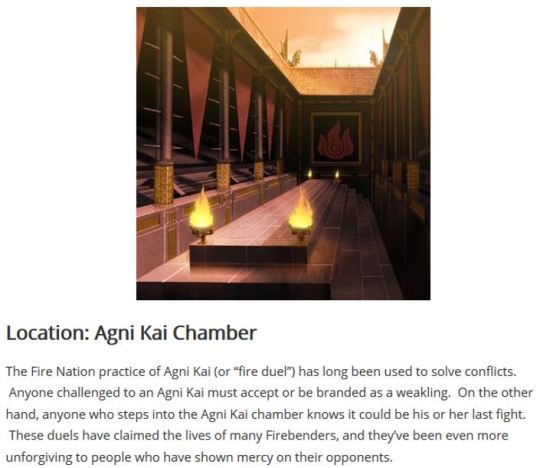

11. Agni Kais are a longstanding component of Fire Nation culture.

12. The Fire Nation experienced an “unprecedented time of peace and wealth” during the era of the Fire Nation, not during the era Fire Islands.

Next, what can be reasonably presumed given what we know?

Something necessitated the Fire Islands becoming unified, but this unification did not result in the Fire Sages taking power, nor did it yield a peaceful, democratic government.

The Imperial Government that resulted from this unification is rooted in military control and maintaining the fealty of its subjects; in Avatar and the Fire Lord, Sozin put on his “ruler persona” to Roku initially before acting friendly, only later to demand loyalty from him as if Roku was any other subject.

The culture of the Fire Nation values strength and bravery from its firebenders, as explained in an official description of Agni Kais. Presumably, the Agni Kai predates the era of the Fire Lord and has been used to settle disputes of various kinds. This could be interpreted as a “non-destructive” means of avoiding war and greater loss of life given how easily firebenders could wreak havoc to wooden buildings and crops (among other flammable components of society). Since nobody recognized Zuko on Ember Island in The Beach, despite his obvious scar, severe scars from burns must be common enough in the Fire Nation that a teen boy having one on his face is not horrifying nor particularly unattractive.

Presumably, the Fire Nation/Fire Islands used to hold its religion and spiritual ties in higher regard, but Sozin’s start of the war required this aspect of the Fire Nation to be suppressed, as implied by dragon hunting and the divided loyalties of the Fire Sages at Roku’s temple, and the fact that various generals and admirals have defected. At the same time, vast enough swaths of the country and its leadership did follow Sozin’s path, considering that he and his family remained in power for over a hundred years. If Fire Lords can have their power challenged, then either nobody tried to stop Sozin, or they were defeated. Azula’s comment about “rumors of plans to overthrow him (Ozai)” in The Avatar State implies betrayal of the Royal Family is not a dormant threat. Though she was technically lying, it must have been a credible lie since neither Iroh and Zuko thought it was preposterous; his brother being “regretful” is what puzzled Iroh, not that there would be plots against the Fire Lord.

Notably, the Fire Lord’s throne room changed between the start of the war and the present day. Prior to Sozin, it did not have the imposing wall of flame as it does now. Certainly it had to be rebuilt after Roku destroyed it, but the wall of flame is much more imposing than the old.

The Fire Sages still pay a role in the Fire Nation, but this role is not known. Presumably, they play some part in the succession of the Fire Lord since they preside over coronation. Perhaps the relationship between the Fire Lord and Fire Sages is similar to the relationship between the Japanese Emperor and the Shoguns, where the Shoguns held the true power in the country (military and administrative) whereas the Emperor maintained a facade of power as a cultural and religious symbol. What is known about the Fire Sages is that they have a temple in the capital and are divided between their loyalties to the Avatar and the Fire Lord.

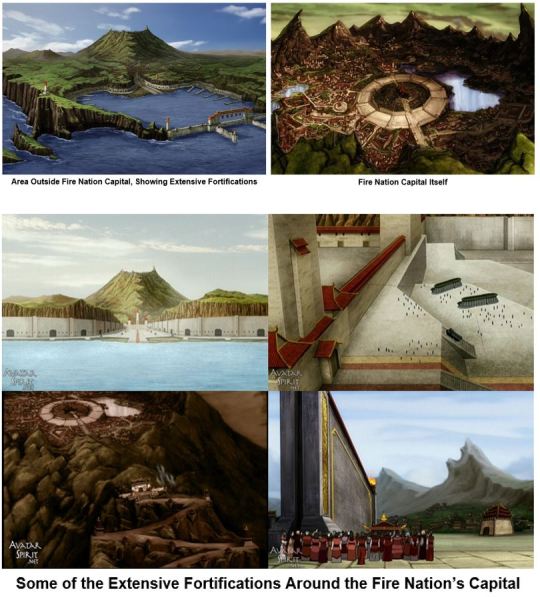

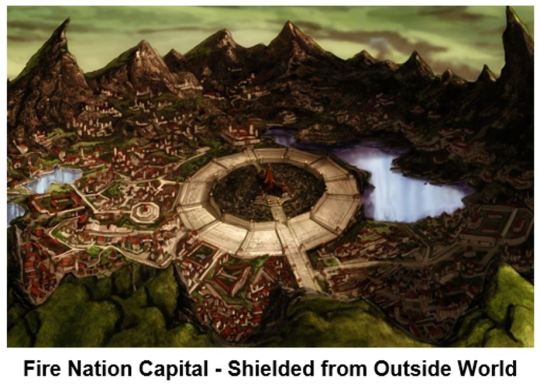

Finally, the Imperial Government’s capital is located in an isolated, fortified city inside a volcano’s caldera, where coming-and-going is strictly controlled. The city is large, full of nobility, physically disconnected from the external port city (versus directly being the hub of economic activity) and contains numerous underground bunkers.

Why would the Capital require such extensive bunkers and fortifications? Presumably because the Fire Lord and Royal Family can be “challenged” and the bunkers are a defense mechanism against both external and internal threats. The Fire Nation did have a “darkest day” tied to solar eclipses, which suggests that the loss of firebending had profound military consequences. Whatever the reasons, the Imperial Government is so concerned about its survival that it has constructed massive fortifications around its capital, implying that warfare is a major concern.

Areas of Confusion

But what does all of this mean?

Was the Fire Nation previously peace-loving and compassionate while Sozin is responsible for all of its “evils”?

Have Agni Kais been performed for centuries and so Zuko being challenged to one was neither unusual nor particularly grotesque for the Fire Nation’s culture?

Did Sozin face massive opposition to starting the war or was everyone humbly obedient to the Fire Lord?

How is a Fire Lord’s rule challenged?

Why wasn’t Sozin overthrown if he had to “impose” the war upon the country?

Why did the Fire Lord come to existence in the first place?

Why has the Imperial Government not been replaced by the Fire Sages?

Why does the Fire Nation need a national government?

What is a more compelling explanation for the Fire Nation’s villains other than mental illness and personality disorders?

As it turns out, there is a way to understand the Fire Nation that adequately fills in the gaps, explains its heroes and villains and provides a lesson on East Asian history.

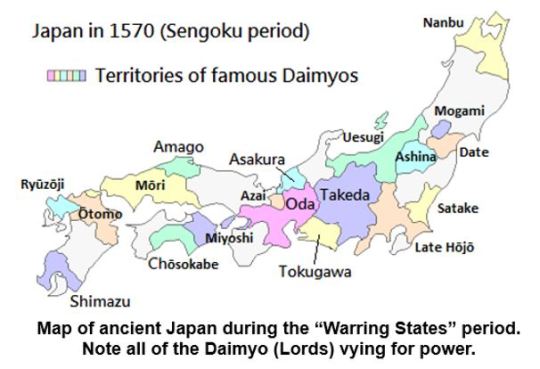

A Brief History of Ancient Japan’s Unification

The islands of Japan have been populated for tens of thousands of years, but the “modern” era of warlords and emperors did not begun until the past 1500 years or so. While the Japanese people were not united under a single state, there was an “Emperor” who was believed to have been descended from a goddess. Despite this first emperor having control over a certain portion of Japan, it did not take long until the country split into separate feudal states.

While the Emperor never went away, their power over the country waned. The real power in Japan laid in the hands of the various feudal lords (daimyo), who used their armies to defend their territories and capture new ones from other lords.

Since the Emperor represented a shared cultural connection among the people, their power was not completely absent. In the earlier parts of history, before the Emperor became completely subordinated, the Emperor would appoint a Seii Taishōgun, or supreme commander, of the Emperor’s armies. Eventually, this “supreme commander” became the actual ruler of the Japan since they controlled the military. By appointing them “shogun” they more or less had the public approval of the Emperor despite the Emperor not actually being able to control them.

Various shoguns came and went, but through it all were the daimyo using their samurai to battle for control of the country. Ruthlessness and murder were common. Building alliances only to later betray them were often wise tactics. For a thousand years, the rulers of Japan lived by the sword, died by the sword and used it to maintain their power. Things got particularly bad during the Sengoku Period, which is considered the “Warring States” period of Japan. That tells you all you need to know.

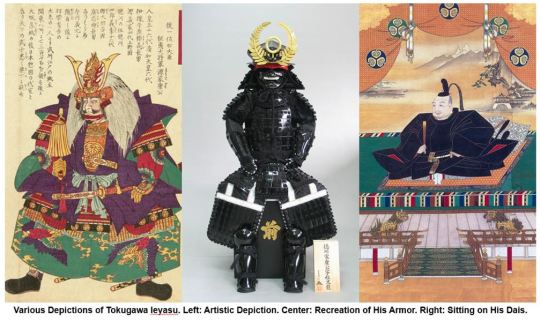

It was during this time that one of these feudal lords rose to power, a man named Tokugawa Ieyasu (first name Ieyasu, last name Tokugawa). Using a combination of political tact, military genius and European steel breast armor, he defeated all other daimyo during the Azuchi–Momoyama period and installed himself as the shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate. This marked the end of over a thousand years of continuous violence and social turmoil in Japan.

The Tokugawa Shogunate represented Japan’s first unified national government. The country’s existing daimyo were placed under strict control to ensure they did not rebel. The military was nationalized and the existing feudal governments rearranged to ensure centralized control by the Shogun in his capital at Edo. Notably, Edo became modern day Tokyo.

National laws were written, along with cultural and religious standards to ensure social cohesiveness, stability and control. The economies of Japan also flourished, especially in the cities. A consequence of the Tokugawa Shogunate, however, was closing off Japan to the outside world. The Shogun wanted to ensure their rule and control of the populace. Allowing other countries to influence them and provide assistance to competing powers within the country was viewed as destabilizing.

A particularly unique aspect of the Tokugawa’s politic strategy was requiring the daimyos’ families to live in the capital while the daimyo themselves had to go back and forth between their homes in their territory (called a domain) and their homes in the capital every other year. The Shogun essentially held the daimyos’ families hostage to ensure they would not rebel or work against him, although they lived in the comfort and relative freedom of a modern city, not as actual prisoners.

Another tactic the Shogun utilized to quell rebellion was to keep careful control of who entered the city of Edo and its surroundings. Guards were at all entrances and major roads and registries were kept of all people. Essentially, if you weren’t suppose to be somewhere, you weren’t allowed to be there.

Bushdio also developed during this period as way of controlling the warrior class, and was much more complicated than most Western depictions. With war and feudal fighting no longer a constant threat, the samurai class became enforces for the new government. Naturally, the Shogun was particularly interested in controlling them.

Control is a common theme of the Tokugawa Shogun’s government.

The Tokugawa Period was one of peace and stability, prosperity and enjoyment of the arts, but Ieyasu Tokugawa was not a nice person. He hunted down and executed the families of rival clans, including kids, during the takeover. He held families hostage and made sure his subordinates feared him and never stepped out of line. He enacted strict laws to control the populace and made sure no one could challenge him and his government’s reign. And it worked. Japan did not experience another war until the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate 278 years later, when the Emperor regained control and ended the era of isolationism. There’s a reason why modern day Japan doesn’t view this period with derision and loathing; given the context of the time, it was a proud moment for a region racked by warfare and division.

A pattern is beginning to emerge: an island nation ruled by feuding lords with no central power to direct them; a religious and cultural figure with no real power; a period of intense warfare and turmoil followed by a lasting period of unification and prosperity; a powerful central government headed by a hereditary monarch who took power using ruthlessness and military might; a hereditary monarch who rules through fear and demands fealty; a capital city with strict control of who comes and goes.

Themes of control and subordination from a central power.

This is sounds very familiar.

The Military and Political History of the Fire Nation

The history of ancient Japan provides a real-world model for understanding the origins of the Fire Nation’s Imperial Government, the Fire Lord and why they rule through fear and military domination. Keep in mind that the Fire Nation is not Japan, but warfare, centralized control and a desire for peace and stability are universal. Ancient Japan’s experience with feudalism, warfare and the eventual peace that came from having a competent central authority can go a long way in applying Avatar’s “East Asian origins” to the Fire Nation and its villains and heroes.

Using the rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate as a template, the history of the Fire Nation looks like this:

The Fire Islands were ruled by various feudal lords. These feudal lords engaged in warfare with each other as they vied for ever increasing control. Firebending was the primary source of these lords’ military might. The Fire Sages were recognized as spiritual and religious leaders by the Fire Islands people, but they did not have the practical power necessary to enforce peace upon the lands.

At the same time, firebending was recognized as being fundamental to the influence of the Fire Sages and the power of the feudal lords. Since fire can destroy houses, burn fields, melt iron and lay waste to non-bending armies, whoever can control and weaponize firebending for their own purposes will attain the most power. On the other hand, this also makes warfare particularly destructive as even small rebellions could lay waste to cities given how much fire a single firebender can unleash.

At some point, in order to put a stop to the fighting, a central authority came to power, either as one of those warlords or a Fire Sage acquiring enough military and political power. Maybe an avatar helped them. Without a doubt, military might had to have played a role in ending the “Warring States” period of the Fire Islands.

In order to make sure the Fire Islands did not fall back into fighting and remained peaceful and stable, this new central authority created a sweeping national government to control them. Thus are the beginnings of the Fire Lord and Imperial Government.

Because the Fire Nation is full of people with ”desire and will, and the energy and drive to achieve what they want” (in the words of Uncle Iroh), the destructive capacity inherent to a nation full of firebenders must be kept under strict control; if the goal is to create a prosperous, flourishing society, you cannot allow it to be destroyed periodically by walking flamethrowers.

As a result, the Imperial Government is not a “friendly” entity. It controls the nobility and lords who act as the local “vassals” in their home territories; it amasses a large, overwhelming military to quash any attempts at rebellion, and to send a clear message to its people to not even try; it uses fear and threats of violence to control the people who might feel the “drive and willpower” to try their hand at acquiring wealth and power through force.

The Agni Kai exists as a means of settling conflict without the destructive consequences of firebending. Perhaps a Fire Lord enacted this to further tamp down on firebenders’ destructive tendencies. It may also be an example of how the Fire Nation’s “warrior class” handles internal disputes in a similar manner as bushido.

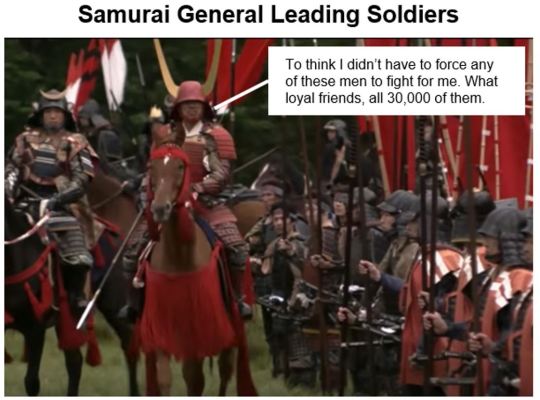

Bravery, ferocity and a willingness to fight are valued in the leadership of the country because the Imperial Government is supposed to be a military entity first; how can the Fire Lord, their family and government inspire fear in the people if the people don’t believe they will be crushed if they step out of line?

At the same time, since the Fire Nation is much smaller than the Earth Kingdom, the Fire Lord must ensure they can defend the Fire Nation from invasion; you need a large, devoted, competent military to go up against an enemy multiple times your size.

In order to further control the country, the Fire Lord requires the families of the lords and nobility to live in the closed-off, guarded capital inside the caldera in a similar manner as the Tokugawa Shogunate required. This is why the capital is so guarded and closed-off, yet beautiful and comfortable; it is both a defensive measure for the administrative officials and a means of holding the nobility “hostage”.

The Fire Lord and Royal Family views themselves as presiding over, and maintaining the peace and stability of the Fire Nation. Their responsibility is to ensure that the peaceful Fire Nation does not fall back into the chaotic Fire Islands. Being nice and democratic is not their means of achieving this; making sure everybody subordinates themselves to the Imperial Government is.

After hundreds of years of peace and an unprecedented era of prosperity, the Fire Nation began to lose its internal enemies. The lords and nobility were under full control. The Imperial Government was vast and efficient. Nobody was trying to invade the Fire Nation. Everyone was happy and proud of their culture and government.

This allowed Sozin to begin looking outward. Using the all-powerful Imperial Government apparatus developed over the centuries, plus the sweeping loyalty to it ingrained into the public, he was able to get the country to go to war against the world. The militarism inherent to the Fire Nation’s leadership was not crafted out of whole cloth but simply cranked up and sent down a dark path.

The military being so willing to go along with it was because of their inherent loyalty to the Imperial Government and their culture of aggression and lust for battle necessary for warriors. This is actually where the 20th century Imperial Japan connections come in, but that’s a separate topic.

In summary, the Fire Lord and Royal Family view themselves as stewards of the peace and order of the Fire Nation. They see their responsibility as doing whatever it takes to prevent the “bad old days” from returning and that the Fire Nation is never weakened by foreign invaders. They rule through coercion and fear in order to ensure a country full of people who can shoot fire out of their hands remain subservient to the Imperial Government’s will. They embrace a culture of fighting because their primary goal is to prevent fighting by deterring those who might want to try.

An Alternate View of the Fire Nation’s Villains

Viewing the Fire Nation’s culture, government and leadership through the lens of Japanese history paints a more coherent picture of the Fire Nation’s villains, versus the M.C. Escher-like theories that result from focusing entirely on mental illness and personality disorders.

Look at it like this: the Fire Lord demands fealty and obedience from the people yet Azula’s emphasis on controlling people through fear is a result of Freudian Excuses and personality disorders?

No way.

Ruling through fear and coercion is necessary from the viewpoint of a soldier-princess who is supposed to command obedience from subjects, or else.

Agni Kais are expected events in Fire Nation culture, so common that child-Zuko is perfectly happy to face the general over mere “disrespect”, but the Fire Lord challenging his son to one is uniquely out of line? It’s awful, I mean, really awful, but it’s not out of line and it says a lot about the ingrained culture of the Fire Nation; Ozai didn’t think it would be viewed as shameful by everyone watching. Keep in mind that the tale of the 47 Ronin started with one member of the nobility insulting the other (essentially) and being asked to commit suicide simply for drawing a weapon inside Edo Castle (strictly forbidden). If Ozai can have his power challenged as any other Fire Lord can, then nobody was willing to oppose him because everyone else supported him.

Iroh spends a lifetime invading the Earth Kingdom, no doubt killing tens of thousands, and he can joke about burning Ba Sing Se to the ground? Of course he can, because it’s what Fire Nation generals do and part of the terrible culture that must be changed, as horrible as it was. The prince-general is supposed to be a military leader and enjoy what he does. He better not be squeamish.

Zuko is expected to be “loved and adored” for having firebending talent, courtly manners (to quote official descriptions of Azula) and intelligence in a similar fashion as his prodigal, early-blooming sister? Yes, because she bloomed early as the type of princess the nobility and leadership want and expect. It’s unfortunate they were so hard on Zuko, but now we know why he wasn’t “adored” like his sister; she was what others wanted Zuko to be.

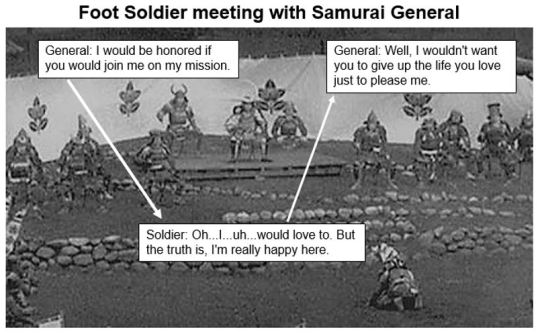

Ty Lee is strong-armed by Azula into leaving the life she loves, even having her life threatened, when Ty Lee is a family member of the nobility that the Imperial Government seeks to control? Of course she is strong-armed. Can you really imagine this scenario playing out:

Those lines are taken from the show. Sounds a lot different, doesn’t it? Ignore the smirking and smugness for a moment and think about what is actually happening: a supreme military leader and heir to the throne is bullying a subordinate in order to get what they are entitled to; unwavering loyalty from a subject. Doesn’t make it good. Doesn’t make Ty Lee’s fear and loathing of Azula any less justified, but it puts it in a much more relevant context than vague theories of sadism and personality disorders. It also tells us something about the real ancient world: this how military rulers in East Asia’s history behaved and now you’re getting to see it in a fictional setting.

Fire Lord Azulon orders one of his sons to execute their son? That’s bad. Really bad. Did you also know that Ieyasu Tokugawa ordered his own son to commit suicide over suspicion he was conspiring against him? He didn’t want to but those were the wishes of the lord he was working with to win the war. That’s really bad too, and not shocking for the era, unfortunately. The leaders of the ancient world valued human life a lot less than people do now. It’s sad they didn’t value it more.

Manipulating subordinates (i.e. playing them off each other) and being ruthless were not frowned upon, but legitimate tactics. Murder and backstabbing were useful means of getting rid of an opposing leader. What mattered was winning, and the blood on your hands could simply be washed off, and if people didn’t like you for it? Well, were they in charge?

None of this is “good”. None of this is moral, or righteous, or anything close to how people should act in the modern era. However, these were not kleptocratic dictators like we see around the world today. These were legitimate administrative rulers by their day’s standards, and we (you and me) will never truly know what they were feeling when they woke up in the morning with the responsibilities of warfare and politicking.

We will never be able to completely relate to what these ancient leaders did. Do you know what it’s like to be the law in the land who can order people to commit suicide, and who will do it? Do you know what it’s like to prosecute a political and military war against multiple opponents across a vast country? Do you know what it’s like to manage an ancient authoritarian government after hundreds of years of warfare and chaos? None of us will, but that’s the kind of situation that a fictional country like the Fire Nation can take inspiration from, and should take inspiration from.

These were all very real problems of the ancient world and problems which Avatar, as a fictional work, can allow us to explore in the safety and comfort of not actually having to be there (and without having to open up huge history books).

Summary

The Fire Nation’s political and military history can be modeled on ancient Japan’s, in particular the rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate, where the Fire Lord represents the shogun and the Fire Sages the emperor.

The Fire Nation capital is both the head of the administration and home to the nobility’s families, who are held as hostages (in comfort) to prevent the various lords from rebelling.

The Royal Family and Imperial Government rules through fear and threats of force because they have to keep a country full of walking flamethrowers in line.

As military leaders who can have their power challenged, firebending talent and military prowess are highly valued and necessary for Fire Lords. At the same time, the rest of the country’s leadership wants leaders who appear worthy of that power and authority, hence those who have all the right qualities (Azula) are viewed in higher regard than those who have less (Zuko).

Azula’s emphasis on using “fear to control people” is not a psychological hang-up but a natural tactic of the Fire Lord, military, and Imperial Government to maintain obedience; as a teenager with limited life experience, she has internalized her role as a princess and warrior to the detriment of her personal relationships and emotional maturity (this is where the “child soldier” narrative has relevance).

Ozai represents the pinnacle of self-interest, authoritarianism and militarism that the combination of Sozin’s War and the longstanding nature of the Imperial Government have combined to create. In the ancient world, lords waged warfare for two reasons: to acquire power or pre-emptively wipe out rivals. Ozai wants power.

Ozai challenging Zuko to an Agni Kai is awful but not unusual, hence why he felt he could do it at all. Agni Kais are a fundamental aspect of conflict resolution in the Fire Nation, most likely because the Fire Nation’s leadership values bravery and a willingness to fight very highly. As Zuko was a prince and future leader of the warrior class, those values applied to him as well, but they got applied to him far too young (again, this is where the “child soldier” narrative has relevance).

And finally, by modeling the motivations of the Fire Nation’s villains and heroes on the military leaders of ancient Japan, you have the opportunity to learn about and critique that ancient society while also giving it a fictional flare.

As a final remark on applying the history of ancient Japan to the Fire Nation, the Tokugawa Shogunate ended when the Emperor forcibly took control of the Tokugawa government in order to end the forced isolationism. If ancient Japan hadn’t been pressured to adapt to more advanced European civilizations (say, if it existed in a vacuum) then the Tokugawa Shogunate might have continued to be the longest and most stable period in Japanese history; post-World War 2 Japan is only 70 years old while the Tokugawa Shogunate lasted for 278. When the Emperor wrested control of the country from the Shogunate, there was already enough peace, stability and government bureaucracy in place to lead a rapid transition of the country into modernity. That was the ultimate value of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

If the Fire Islands had not unified under a central authority, then they might have never industrialized so rapidly during that “unprecedented time of peace and prosperity” and may have eventually been conquered by the Earth Kingdom (should an EK conqueror have found a way of killing the Avatar, or taking advantage of their absence).

Conclusion

Think about ancient Japan for a moment. All of the warring lords. The conquest and ruthless political maneuvering. The ruling through fear and totalitarian control. What is a more reasonable explanation for the behavior of that society: mental illness and personality disorders, or universal concepts of ancient nation-building?

What makes more sense for furthering Avatar’s East Asian themes in terms of the Fire Nation: sociopathy, personality disorders, lack of fundamental human qualities, petty bullies and insecure abusers? Or universal concepts of ancient nation-building in the context of people who can shoot fire out of their hands?

Was Ieyasu Tokugawa suffering from a personality disorder? Was ancient Japan swimming with people who lacked fundamental human traits? That would be and absolutely extraordinary anomaly of human genetic variation.

When discussing the evils of the Fire Nation, you have to start with the in-world context that created them, and in order to understand that context, you have to apply some East Asian history. Why “decent” or “normal” people end up doing terrible things is a question as old as humanity itself and should not be erased from Avatar.

In order to understand why Ozai and Azula seem like “bad” people to us, it’s because the rulers of ancient Japan acted like bad people. Zuko can’t be soft and fumbling. Azula can’t let people say no to her. Iroh can’t abandon the siege with no consequences. Ozai can’t let Zuko refuse to fight. As bad as many of these things are, they are driven by the fact these people are the most powerful entities in their country and must show their fire-wielding subordinates that they deserve their power and should not be challenged. There is no room for weakness, only strength and competence.

When you resort to psychological theories or genetic anomalies to explain the Fire Nation’s villains, you erase the opportunities to tie the Fire Nation to critical elements of East Asian history, namely the rise and success of the Tokugawa Shogunate. By relating the main villains of Avatar to the very real “villains” of the ancient world, you preserve the East Asian themes that make Avatar unique and informative to a Western audience and help shed light on what drove them to be what they were.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the Labels: Tangerine

Released in 2015, Tangerine, a film centered around transgender sex workers, follows the story of two bestfriends Sin-Dee and Alexandra, who are on a mission to find Sin-Dee’s boyfriend/pimp, Chester, who is accused of cheating on her while she was in jail. The two best friends set out to find Chester, as well as his mistress, Dinah, who is a cisgender white woman, immediately after Sin-Dee’s release from jail. Through their journey, the two encounter obstacles related to drugs, sex-work, romance and violence. In order to better understand the impact of this film, concepts such as queer production, transgender visibility and intersectionality will be discussed in relation to dominant idelogies portrayed throughout the film, such as gender, race, constructions of sexuality, class and ability.

The production of the film generated just as much buzz as the film itself. Shot on an Iphone 5 with a low- budget estimated around $100,000, director Sean Baker had a tight budget to work with. Issues surrounding queer production in Hollywood become apparent with films like Tangerine. Not only do questions arise about the lack of funding and resources for queer media, but concerns related to who is producing queer narratives also come into question. Sean Baker, a heterosexual cisgender white male, produced a film about transgender woman of color without being able to identify with their struggles or identity. In the article, “Pose(r): Ryan Murphy, Trans and Queer of Color Labor, and the politics of Representation,” author Alfred L. Martin Jr. further examines why representational politics is problematic in Hollywood in relation to the labor issues and white savior image within Hollywood. As a heterosexual cisgender white male, director Sean Baker profits from the production and storytelling of transgender people of color. As stated by Martin, “the fact remains that it is his white capital within a fundamentally racist industry that allows Pose to be made” (Martin Jr., n.p.). This narrative is problematic due to the overwhelming fact that transgender people of color still face adversity, whether from violence, homelessness, health failiures etc. while a white heterosexual or homosexual male is allowed the opportunity produce and ultimately benefit from their stories. Not only are labor issues in Hollywood problematic due to who is able to produce narratives of transgender people of color, but the image that a white male serves as a ‘white savior’ also becomes problematic. Queer audiences and the overall population is ultimately convinced that in order for transgender people of color to have a voice, white producers must be the only ones who have the resources and ability to produce such films.

Factors surrounding trangender visibility become evident with the films dominant ideologies surrounding class, gender, race, ability and constructions of sexuality. In the film Sin-Dee and her best friend are introduced as transgender black woman who are at the lower level of the class spectrum. In the article “Breaking Into Transgender Life: Transgender Audiences’ Experiences With “First of Its Kind” Visibility in Popular Media,” the author, Andre Cavalcante, discusses the importance of “breakout texts” as a form of audience-text interaction. In Tangerine, for example, the narrative that surrounds transgender people of color is negative and stereotypical. Negative portrayals of Sin-Dee as poor, violent, loud, assertive and codependent all shape and influence audience perceptions. As stated by Cavalcante, “the fates of transgender individuals and communities are understood as intimately linked to the films’ representation of transgender” (Cavalcante, p.3). Consequently, the image of transgender people of color becomes threatened by media portrayals when characters are solely introduced as possessing one narrative; usually negative. However, the film does introduce an unfortunately real narrative about survival and isolation for transgender people of color. Similarly, the film offers audience members the opportunity to create their own cultural interpretation, whether realistic or not, of transgender people of color. Although negative interpretations may arise, Tangerine reveals the various hardships transgender people of color experience in their day to day lives. For example, both Sin-Dee and Alexandra see sex-work as a necessity for survival. Although their gender and sexual identities are at times questioned, both women risk their lives to make money due to a failure in protection, discrimination and harrassment experienced in the work place and their everyday lives. Thus, questions surrounding transgender visibility arise. In the article, “Queer and Feminist Approaches to Transgender Media Studies,” by Mia Fischer, the author suggests that although an increase in transgender visibility has occured in media and national discourse, the representation of transgender people in media does not provide improved living conditions for the overwhelming majority of transgender people (Fischer, 102). This is particularly important when discussing and approaching intersectionality in “scholarship and social justice activism that moves beyond visibility politics and ruthlessly deconstructs oppressive systems and our own complicity within them” (Fischer, 103). In a system where racism, classism and (cis)sexism is at the core of opressive actions against marginalized communities, neither feminist, academic or queer activist can continue to exclude the voices of transgender voices. Without the inclusion of transgender voices, activist and scholarly groups cannot actively formulate strategies for resistance that cater to all marginalized groups. This is important due to the countless erasure of transgender voices in history. In order to continue fighting towards social justice, women like Sin-Dee and Alexandra must be heard and given the proper tools to simply continue living.

youtube

Sin-Dee’s and Alexandra’s intersectional identities further introduce the multidimensions that contribute to their struggles. In the article, “Queer and Feminist Approaches to Transgender Media Studies,” by Mia Fischer, the author states “I take intersectionality as a key framework for understanding how mediated representations of transgender people are linked to their daily interactions and experiences with systems of state power and violence” (Fischer, p. 99). In Tangerine, the last scene where men are seen yelling homophobic slurs at Sin-Dee and throwing urine at her accurately depicts the leveles of violence and powerlessness experienced by transgender people. This interaction between Sin-Dee and the men in the car is based on how the men identified Sin-Dee through her appearance and voice. Unfortunately, this scene serves as an example of how transgender people experience daily interactions associated with powerlessness and violence. In another clip, Alexandra is seen arguing in front of a cop car with a white middle aged man. In this scene, Alexandra is persistent about the money this man owes her while he urges the cop that she attacked him unprovoked. The cop proceeds to refer to Alexandra as “him” and Alexander to her partner on the job before getting out of the car and only checking Alexandra’s pulse for any signs of drugs while the man is given a warning to leave voluntarily before he has to alert his family of why he needs bail. This interaction perfectly represents how people in power view and handle transgender people of color. The man is given a pass, while Alexandra is humiliated and unpaid for her work. As a transgender woman of color, Alexandra is at a disadvantage socio-economically, in comparison to a white cisgnder heterosexual women. Alexandra’s intersectional identities, black, poor, sex worker and transgender woman all attribute to her day to day hardships and experiences.

youtube

As a young heterosexual college-educated woman of color, my own subject position allowed me to further examine how my various identities factored into the way in which I engaged with this film. While watching the film, I was able to empathize with both Sin-Dee and Alexandra as a woman of color. However, as a heterosexual cisgender woman, I am not able to relate to the struggles transgender woman of color face. Despite my inability to relate to Sin-Dee’s and Alexandra’s gender identity, topics surrounding transgender media studies influenced my ideologies around transgender woman of color. As a minority in America, this film is important to me because it dives into the unjust treatment and life of transgender woman of color in America. Although I myself will never experience what it means to be a transgender woman of color, it is important for me to continue the path of educating others and myself on how to be an ally for the LGBTQ community. Despite its flaws, Tangerine is raw and unforgiving. The film is exemplary in depicting the harsh realities transgender woman of color face whilst leaving its audience with an unsettling feeling. Ultimately, I was able to understand how intersectional identities as well as queer portrayals coexist to shape how audience members and queer people view and identify with queer media.

Cavalcante, Andre (2017). “Breaking Into Transgender Life: Transgender Audiences’Experiences With “First of Its Kind Visibility” In Popular Media.” Communication, Culture & Critique, 10(3), 538-555. https://academic.oup.com/ccc/article-abstract/10/3/538/4662971?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Fischer M. (2018) Queer and Feminist Approaches to Transgender Media Studies. In: Harp D.,Loke J., Bachmann I. (eds) Feminist Approaches to Media Theory and Research. Comparative Feminist Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90838-0_7

Martin, Alfred L. Jr (2018). “Pose(r): Ryan Murphy, Trans and Queer of Color Labor, and the Politics of Representation.” LA Review of Books.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nott’s Conflicting Narratives

[[Spoilers for Campaign 2 up to Episode 75]]

Man. D’you ever get the need to talk about how much you love your favorite character? Because I am feeling PASSIONATE for a specific little goblin girl right now.

I love Nott. She’s the peanut butter to my jam, the sugar to my spice, the awkward green butterball mushing around in my heart. She’s my absolute FAVORITE character of the cast and one of my all-time favorite characters in general. So, of course, I feel the need to bend over backwards, snap my spine into a pretzel, and projectile vomit my absolute love for this woman all over your dashes.

In this piece, I wanted to talk about her personal growth over the story and how she’s evolved from what viewers believed was merely a skittish, oddball of a green powder monkey klepto into an equally odd but emotionally resonant mother desperate to reclaim her life and family.

In my opinion, Nott’s overarching story revolves around a mother attempting to recapture her personal narrative from a world that has tried to tear it away from her.

Let’s first establish Nott’s position as the “mother” of the Mighty Nein.

Time for a recap.

As we discover in episode 49, Nott is a little goblin girl, who was once a young halfling woman, who was once a halfling child. In her desperate dash to protect her family from goblin kidnappers, the halfling woman known as Veth Brenatto is recaptured and put to death. Her corpse is then reanimated into the flesh puppet goblin suit we know and love today. In this process, her skin, body, and even mind are reconstructed to be more goblin-esque – a situation which Veth vehemently despises. To put distance between herself and her former life, she renames herself “Nott the Brave,” an anagram of Veth Brenatto.

“They made me everything… that I thought I was. Not pretty…not good. Just not.”

This event is significant for a multitude of reasons, primarily of which revolve around Nott’s relationship with motherhood.

In her essay The Symbolic Annihilation of Mothers in Popular Culture, Berit Astrӧm (2015) observes that mother characters are routinely devalued in popular culture via what she terms “symbolic annihilation.” Gaye Tuchman (1978) originally coined the phrase to describe the way in which media trivializes, condemns, or outright excludes mothers, but Astrӧm extends it to include the removal of mothers from narratives entirely.

We’ve seen this play out time and time again: for example, how many times have we questioned “what happened to the mother” in Disney movies? Often, we see that their exclusions leave little impact on the story and characters, with many media franchises unceremoniously minimizing the mother’s very existence as if it held no more meaning than an ironically titled paperweight.

Now, how does this apply to Nott?

Nott’s character is an inversion of this trope. Although she is killed by the goblins as per the trope’s wont, the narrative does not revolve around her son or husband trying to cope with her loss. Instead, the narrative remains centered on she the mother as this little goblin girl punches a fist through the earth and screams NOT TODAY SATAN. Her story revolves around her identity as a mother, and it takes shape in a plethora of different ways.

Nott exhibits many atypical characteristics that are not commonly associated with the idealized form of “motherhood.” She’s loud, she’s boisterous, she’s mischievous. She’s self-admittedly “strange” and eccentric. She saw it suit to dump a pitcher of cucumbers and proceed to eat them off the ground. Absolutely no one can convince me that this a goblin-specific trait and not just Nott being her weird little self.

And yet, Nott exhibits many typically feminine/motherly traits as well. In spite of her vulgarities, she’s gentle and kind towards Caleb, and it takes some time for their relationship to evolve beyond that. She likes dresses! She likes feeling pretty even though the situation rarely allows her to be. She likes to collect buttons and baubles and cutesy trinkets. And most of all, Nott expresses love. Beau’s the first person in the group to say it to someone else, but Nott is the first of anyone to emphatically express her love for this ragtag group of misfits they’ve wrangled together.

“I know we have things to do, and I want to do them, but the reason I want to find these people and rescue them is not to use them, or not because we’ve invested time in them. But it’s because… I love them.”

Nott is very much “the Heart” of the Mighty Nein, in spite of her idiosyncrasies and eccentricities. In this sense, she views herself as their mother – not just as Caleb’s parental figure, but the entirety of the group. It’s not just a meme, with adoption papers scrawled across a series of barbeque-stained napkins in chicken scratch. Over time, she’s genuinely adopted the M9 as her own, welcoming them under her stubby wings. Nott has said as much several times, but most significantly in episode 76, when she told Caleb that she wanted to protect everyone on their own individual quests.

“I protected you so that you could go on your journey and find yourself and fulfill your quest. I feel like I’ve got to do that for everyone now because, I don’t know, deep down inside it feels like my quest might not be done till everyone else has figured out who they are and what they want in this world. Everyone’s seeking something, you know?”

This protection – this overwhelming need to shield, to safeguard, to provide security and aegis – is crucial to recognizing what Nott is as a parent. A protector. A defender. Nott firmly believes that protection is representative of parenthood, its indistinguishable mirror image.

How do I know this? Nott confirmed it word-for-word in episode 13, when she explained her relationship with Caleb to the rest of the M9.

“Caleb and I have a very special…relationship. And it’s that of a parent and a child. But I am the parent, you do understand that, correct? I protect him. He’s my boy, and I keep him safe. … It’s my job to protect him, because I love him, and I am his protector.”

Nott clearly associates parenthood with protection. She reiterates it again and again. If you fall under her protection, you are her child. It doesn’t matter how old you are, how strong you are, how quick you are – she will protect you to the very last inch of her life. And over the course of the campaign, many, many times over, she’s nearly given said life to ensure the protection of others. An early example is when Nott threw her body over Caleb’s to shield him from attack. In 45, she drew the blue dragon’s attack to save Jester, shaving her hit points down to 1.

Nott again establishes this in 76.

“So I feel like, I need to be there to protect you all. To rescue you when there’s a dragon about to kill you and use my body as a shield; or to pull Beauregard out of the mouth of a worm; or to catch you when someone falls with a feather fall spell.”

This is a fundamental aspect of her character, and explains the majority of her actions. Even though she’s anxious and scared, Nott powers through her fears to protect her loved ones at any cost necessary – with a few nips to soothe her nerves, of course.

And as sweet as this gremlin of a goblin is, she doesn’t extend her protection to everyone she meets – she’s self-sacrificial, but only to her proverbial children, after they’ve spent more than enough time becoming comfortable with one another. In episode 75, for example, Nott suggested that Reani was expendable and thus should go first when facing the dragon. She likes Reani, sure, but if it came down to her and the M9? The outsider would be the first to go.

This further lends itself to the idea that Nott perceives protection as parenthood, self-sacrifice as motherly duty – she’s not just a nice gal throwing down her life in order to ensure the welfare of others, but only for the select few she deems in need of her protection.

However, Nott isn’t just a mother, which comes to the crux of this post. For the majority of the campaign, Nott has primarily identified as a mother figure – to Luc, to Caleb, to the M9 at large. But over time, she’s steadily developed into wanting to be more than just a mother. At the very least, she’s expressed her desires more openly over the course of the show as time has gone on. This development intersects with her identity issues as Nott struggles to reconcile two conflicting lives.

Throughout her short life – and I do mean short, she’s only about 25 (I’m turning 25 this month and the extent to which this little goblin has pushed herself through sends me into anxiety just by association) – Nott’s life has followed a very, shall we say, standard route. She’s always been someone’s daughter – someone’s wife – someone’s mother. Veth Brenatto grew up the small town of Felderwin with very few expectations of their people beyond the usual sort, assuming that said small town followed real-world small-town culture. As such, Veth traversed domestic paths in life, not straying far from those expectations. In spite of her intelligence and capabilities, Veth remained a housewife essentially, assisting Yeza when need be and taking care of Luc. This narrative held steady for some time.

And everything changed when the Fire Nation goblins attacked.

Veth’s narrative as a mother, as a wife, as a little halfling from the little hovel hole of Felderwin, was abruptly disrupted when she became Nott. Her narrative was stolen from her, manipulated and perverted into something she deemed grotesque. Forced to co-exist with the tribe, Nott becomes the torturer’s assistant – the absolute antithesis to motherhood in the representative forebearer of violence, depravity, and death. Her desire to nurture and protect is met with oppression and bloodshed.

It’s no wonder Nott detests the narrative the goblins thrust upon her. Her goblin exterior fundamentally represents a life forced upon her, a narrative chosen without her consent.

“I just don't like how I feel when I see my hands or my feet. They just feel wrong. I want to be different.”

“I'll be honest. I've started forgetting what it feels like to be a halfling, to be me. I don't remember everything any more. I feel like every day I'm more and more goblin. I don't like it at all. I don't like myself at all.”

“There's still something that's not right about this. This is not my body. It's just not me. And people liking you is nice, and people accepting you is nice. But if you feel wrong inside your own skin, then, well, you can't be a good mother or a good wife, or a good anything, really.”

Upon escaping, her narrative again changes: she’s no longer anyone’s assistant, but existing for herself. And only herself. Before she meets Caleb, she’s alone, unwanted by the populace at large and unable to return to Felderwin. She’s no longer a mother – just detested vermin looking to steal and connive, so people would believe.

That is partially why, in my opinion, she adopts Caleb as her own so quickly. Of course, Nott sees him as a means to an end in the beginning, as does he. They both admit that they had ‘other intentions’ in staying together than purely out of goodness of their hearts. However, it is evident that well before the campaign started, these two forged a bond that went beyond that of convenience. Nott fills the hole in her heart, the hole in her very narrative, by becoming Caleb’s adoptive mother, assisting him in his ventures and protecting him whenever need be. By doing this, she is able to choose for herself, to differentiate herself from the goblin’s narrative of pain and misery. She is no longer just “not,” she is Nott, Nott the Brave.

As was aforementioned, Nott’s motherhood narrative grows to include the rest of the M9. However, with time, she reaches a conflict within herself: while she hates being a goblin, she enjoys her new lifestyle. Is she afraid? She’s fucking petrified. Yet like the rest of the group, she’s fallen in love with adventuring, the highs and lows that demonstrate the extent of her capabilities. Nott isn’t just an assistant anymore – she can do magic! She can fight, she can pick locks, she can adapt firearms and create explosive weaponry. Hell, she can wield a crossbow with the dexterity of an Olympic gymnast and liquidate giant spiders into bloody pastes on the wall. With the M9, she’s seeing the world, far beyond the borders of Felderwin and her small-town life.

And suddenly, Veth’s narrative as a stay-at-home mom isn’t so appealing anymore.

Is there a problem inherent to existing as a housewife and full-time mother? No, of course not. Nevertheless, Nott has found herself in a strange position – she longs for her old life and family, ripped away from her by the gnarled claws of fate, yet remains enthralled by the wonders this new narrative can offer her.

In 36, Nott reveals to Cadeuceus that she believes the M9 could be representative of a new life for her – a new narrative.

“I’m not a religious lady, but I will tell you that, for me, this journey with the group has been a bit of a sign. … A sign that there could be, for all of us, another chapter.”

It’s a new chapter, a new narrative, a new life for Nott. One she could never have imagined possible for her in the confines of her small town. And by god, does she want to live it. Nott expressed this desire to live this life to its fullest, to live this new narrative to its fullest, in 27 after Molly’s death.

“Mollymauk was a rainbow man who represented life at its fullest. And. That’s what I want, even more than… even more than what we’re going for before. Together, we’re sort of living life now, aren’t we? And before, we were… in the darkness, so. … I want to find them so we don’t go back to the way it was, when we were hiding in the shadows and, and ducking into alleys to get away from people. We were safe, but we weren’t really alive, right? With these people, we’re having fun and winning contests. And. And killing bad guys, and rescuing children…it’s amazing.”

I’m of the opinion that Nott’s speech is reflective of both her experiences with Caleb as well as her own in Felderwin. She was living before – and she enjoyed it, yes! She obviously loves Yeza and Luc. But now, she’s seeing what life can be like when lived to its fullest, seeing what life can be like when she spearheads her own narrative. She gleans inspiration from Mollymauk, who decided to head his own narrative and remain unrepentantly unconcerned with what his past might have been like. With his death, Nott becomes convinced that she needs to truly lead this life, lead this newfound narrative with this family she’s amassed.

But with that realization comes conflict once the dredges of Nott’s previous life begin seeping into her narrative. This is especially once Nott reunites with Yeza in Xhorhas.

“Caleb, I’m feeling uneasy. … I, because. What the fuck am I doing here? I just was reunited with my husband, and I’ve – I -- we were given a chance to go on an adventure and I jumped at it like that. Am I a bad person? I just left him, I ditched my husband in a den of monsters to go adventuring with you.”

Rather than hold down the fort with her newly reunited husband, Nott instinctively leaps at the chance for adventure, the chance to go out and see more of the world. She doesn’t even think about it, it’s just oh? A side quest? Well fuck me rosy, time to knock my crossbow. Because that’s what Nott would do, not Veth. And once she realizes what she’s done, Nott begins wondering if she’s a terrible person for living her life. She begins questioning her intentions, wondering whether her actions are the ploy of some subconscious desire to remain free, remain independent of her responsibilities.

“You don’t think I’m just…delaying the inevitable? Scared of going back to my old life, or anything?��

Nott further recognizes the disparity between her two lives and how wide the gulf between them yawns.

“It’s just, I just don’t know like. Is he gonna…even like me anymore, I’m so different. Not just physically, I do different things now. … Will I like it? I’ve gotten a taste of adventure and, and seeing the world, and now I’ve gotta go back and be a…a housewife again?”

Nott doesn’t even know if she wants to be called Veth anymore. Not by people who have come into her life since Veth’s apparent demise. When Caleb asks her in 59, she dismisses the question and asserts that they should just go with Nott for now.

She asks Caleb to tell her what she should do, in a desperate plea for someone else to give her direction in life. Because driving your own narrative is hard. It’s a painful, painful process, full of ups and downs and mistakes and setbacks. But Caleb fundamentally cannot decide her narrative for her -- it’s Nott’s narrative, not his. He can help her along and support her, but he will never be able to direct it. She has to do it for herself.

(As a side note: I love, love, love how far Nott and Caleb’s relationship has come. Prior to the Xhorhas arc, Nott never bothered him with her problems, drudging on ahead as she didn’t want to “distract” him from his personal quest. She’s exactly like a mother, masking her insecurities and fears from her young child so that they won’t worry about what they can’t control. And now, as her child has grown up and become more aware of his mother’s struggles, she’s leaning on him more and more for support. It truly mirrors parent-child relationships and is representative of how far these characters have grown over time.)

With these conversations, it becomes evident that Nott is seeking more than family, more than the life of a housewife. And yet, simultaneously, she embodies the narrative of a mother, loves being a mother, and loves the people in both her immediate and found families. To merge these narratives will be an almost insurmountable task, from her perspective -- how can you raise a family when you’re constantly adventuring? You can’t endanger their lives. Conversely, is it responsible of a parent to endanger their own life, potentially risking everything for adventure’s sake? To widow your husband and orphan your child if something goes horribly wrong? If she becomes a housewife again, how long can she keep up the charade pretending she’s a halfling? If she stays, will she forever remain uncomfortable in her own skin? How long will she even live? Nott is juggling so many plates, and dropping even one could result in the partial devastation of these narratives she’s cultivated.

And she’s scared. She’s really, really scared. Nott is petrified of what comes next -- she knows it’s inevitable that she’s going to have to face these conflicting narratives in the future. She knows she can’t ignore it forever. And that prospect terrifies her. She says this explicitly in episode 69.

“I'm just scared, that's all. I'm scared of...I'm scared of what happens next. You know? I don't know what's going to happen after this. I found my husband. I found my son. And I want to go back with them so much. ... But I'm worried that if I go back, that'll be it.”

This overwhelming, paralyzing sense of fear has driven Nott to drink. Even more so than usual. Over the course of the show, Nott has made no secret of her drinking habits. She’s a drunkard -- she knows it, the M9 knows it. You, me, and the NSA agent watching you behind the screen know it. But it’s no accident the M9 has begun commenting more and more on her habitual intoxication. She simply is more intoxicated than usual. She’s depending more and more on her alcoholism to get through each day.

Nott is of course afraid of enemies, of secret dangers lurking behind every corner. She’s a perpetually anxious person, constantly filled with frenetic energy. But these anxieties have worsened ten-fold with the inclusion of her intersecting narratives and responsibilities. And honestly? With all that going on in her brain, Nott just flat out doesn’t want to think about it. She wants to live in the moment -- not in the past, not in the future, but the present.

“I'm thinking about things. And I don't want to think about things. I don't want to think about anything. I just want to be on an adventure with you guys and that's all I want and I don't want to think about anything else past that.”

And so, she turns to drinking. As she tells Caleb, drinking is her own form of self-care. While she may protect others, she herself needs protection too -- from her own thoughts, fears, and inner demons. From the physical dangers that manifest in front of her very person.

“I know you all have my back, I know you all care for me, but no one has my front. So this flask that I drink from, it’s not for fun, I’m not taking nips because I’m looking for fun. If I wanted fun I’d be in Nicodranus with my family. This flask is my shield. It allows me to do these things, to go forward and to protect all of you.”

Nott needs to shield herself from fears that she may not come back to her family. She needs to shield herself from fears that she won’t find a remedy to her situation, that she won’t ever be Veth again. She needs to shield herself from fears that these conflicting narratives will never reconcile, thereby isolating her from either family she’s come to love as her own.

All in all, Nott is currently torn between two lives -- one whose existence is linked to traditional motherhood, and another whose fate is yet undecided. And yet, by continuing with the M9, Nott has found herself on the path towards potential self-realization. This route she treads has the potential to shed the narrative the goblins thrust upon her and totally make one anew, one that is her own. In that sense, it’s representative of what this narrative means as a whole: Nott is more than just a mother. She’s a mother with autonomy. A mother with hopes, dreams, and aspirations. Unlike Berit Astrӧm’s (2015) analysis of symbolic annihilation, she is more than just a paper cutout of idealized motherhood left to be abandoned.

Indeed, Nott can be a mother without being the mother archetype.

Nott will certainly struggle to reconcile these narratives. She loves being a mother, but she clearly wants to love herself too. She wants to be more than just a mother, and thus she quests to recapture her personal narrative -- one where she can be both a mother and retain her personal autonomy.

I love the nuance and complexity Sam has demonstrated with this character, and I’m sure we’re only going to see more in the future.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scraps of Dreams

Commission for anonymous who wanted Corvus x Proxima smut!

(Did I mention commissions are open again? Cause they are!)

Rating: Explicit (aka shameless smut)

Corvus x Proxima

or: Thanos: Death Sentence left their sexual tension unresolved so I fixed it. Anon wanted Corvus to be more dominant and give his wife a little TLC.

* * * * *

The hotel room they lent him was fifty stories above what could be considered ground-level for a city that felt built into a fault line, with streets and skyscrapers varied in length and curvature like personal desire, not reflective of an idea but of a transitive notion of accomplishment in its smallest form to amass into something bigger than mere individual value. Corvus Glaive supposed the want to leave proof of one’s existence in the universe stemmed from the underlying oppression of meaninglessness. To find purpose or to forge it.

It came as no surprise when he thought it all a waste.

* * *

They didn’t talk about what transpired today. Not the emotional ups and downs, or the political navigations, or the pathetic mess Corvus had been afterwards, realizing he might have finally reclaimed his destiny at his rightful Master’s side. It was difficult to process, let alone address, the hazardous accumulation of transgressive narrative from the last few hours. In fact, it felt like an utter chore to say anything at all.

Proxima had her body turned away from him as she undressed in favor of clothes that reminded him suddenly of their normalcy; he didn’t have to see her face to know her exhaustion was present, palpable, even, with how she moved like her limbs were filled under their surface with water. In the low light from the fluorescence of the city outside, her body took on the quality of water, too—translucent blue, hair rolling up and crashing down across her back, her motions so overstated by the constant occurrence of mere existence he wondered if he might just buckle under the weight of her enormity.

“Oh, Midnight—”

It had been so terribly quiet. His words shattered the very foundation of stillness. She snapped her attention to him, eyes widened, doe-like, in the low ambiance of illumination.

“Yes, my love?”

Corvus was beyond modesty, especially in the dark, where the shadows accrued across his lithe chest to replace the cloak he’d left thrown carelessly on the desk chair. He knew his horrible visage was worsened in the night. A beast by nature, or by universal law to counterbalance all the do-gooders that were compelled beyond his understanding to Make Things Right, assembled of equal parts horrible intent and predatory design. Maybe he was merely accustomed to justifying his own happenstance.

He said to her, “I think I will never know if I’m making the correct decisions,” and thought of the time he’d seen Black Dwarf break open a Shi’ar’s ribcage to expose their tender, beating heart, and the way it jolted, jolted, jolted in its meaty cocoon. The explicit, horrible vulnerability. “I think I will never know certainty again. What am I supposed to do when my life has been devoted to all that which has amounted to nothing?”

Proxima approached him slowly. She was the opposite of hesitation, always moving and speaking and thinking with the same absolution of momentum; a constant force awaiting a collision regardless of pace.

“My darling,” she whispered to him in the dark, her hands framing his face. “Am I nothing?”

They hadn’t been alone with each other in nearly five standard months. He’d been reminded of his loneliness when they reunited, albeit briefly, earlier that day—the swollen warmth of her mouth, the bend of her skin in his hands, their insatiable togetherness under the veil of his office shadows.

“That is not what I meant,” he said, stroking her cheek with his thumb. Without his gauntlets or battlesuit to disrupt their closeness, he could feel the lingering static of her power traversing the neurons under her skin, jumping to his fingertips by proximity. Something inside him unknotted. “No, you aren’t. Of course you aren’t.”

“But are you?”

That was how he felt, sometimes, when he wasn’t in her presence. “No,” he said, pressing lazy kisses along the length of her jawline, noting the dampness of her scent with each sudden intake of breath. “Yet, as of late—”

One of her hands went to the back of his head and anchored him in place. Their exposed skins, gray-on-blue, blue-on-gray, melded together, indistinguishable in the low light, in the encompassing darkness. “We are trying to get our footing,” she said. Her logic (and, he thought softly, her love for him) stood as a counterpoint to all the instances in his life that made him feel less than what he’d earned. “No matter where we are, when we are, or why—you are everything to me.”

He trembled in her embrace. He wanted to echo her words, to intake the sanctity of their marriage and every little fulfillment, and transpose it all into the atrocities of war, or of whatever was required of him, with or without purpose; to tear, to maim, to love. The truth of them.

“I am nothing without you,” he said, his mouth hot against her skin. His confession rang through her mind clear as a bell struck calmly and with total acceptance. “Oh, my dear Midnight.”

His teeth captured the soft junction of her neck, stimulating her nerves. She groaned at the reception of the desperate, self-contained violence in his actions. He bit her hard but not hard enough, the method of practiced power that didn’t hurt when it so easily could. Her leg entwined with his. Her fingers curled against his ribs, splaying out where she could feel his pulse fluttering beneath hard bone.

The wet heat of her lips pressed to the blade embedded in his skull, which tethered him to his unending existence, and he reasoned there wasn’t any meaning in that either.

“Take me to bed.”

* * *

Most times, the victor was decided by the basis of conviction alone, filling the precious time allotted to them with little, violent tendencies until one surrendered the struggle. If they hadn’t been interrupted by their Kree escort earlier in the office, Corvus suspected he would have retained the utter dominance that compelled his desire to make Proxima come for him right there against the wall. But he was so debilitated by exhaustion that his sense of time skewed at the edges where one memory met another, and it felt to him like that morning occurred in an entirely different time and place. He didn’t have the energy reserves in him to instigate or resist.

Proxima pushed him easily up against the cool metal that composed the headboard. She must have noticed his absence of strength because he saw the way her head tilted in silent questioning, suspending her weight above his left thigh. “My love?” she said, stroking the centerfold of his chest with her forefinger.

“Your beauty is distracting.”

Her thumb slipped into the waistband of his undershorts, running casually over the jut of his hipbone and raising bumps on his ash-gray skin. “I can be distracting in other ways.”

It felt natural to be alone with her again. He growled low in his chest, and his hands worked their way up her sides to her full breasts, contrasting her rain-cold skin with the dry heat of his palms. “I’ve missed you terribly,” he said, kissing the center of her sternum. “I often refrain from asking too much, however—”

“You can ask anything of me.”

“Then I want to enjoy this night. I want to worship you.” His hands went to her hips and he pushed her back, meeting only a moment of resistance from her weight before she submitted to his motions. He laid them out across the bed, which became, he thought, suddenly too small for the conjoined mass of them both. “Slow,” he added. “It’s been too long since I’ve given you all of me.”

Proxima’s expression was one of knowing. She guided his chin down and kissed him, always combative by fault of genetic disposition, her tongue pushing against his own and her teeth working at his bottom lip; she brought them so easily together in the privacy of a room he’d slept in for months alone, not easily, and only out of necessity.

Corvus gazed at her as she worked his mouth open, but she must have sensed his attention was on her because the pads of her thumbs pressed against his eyelids, forcing them closed. He became acutely aware of the featherlight pressure in her touch and how easily she could crook her fingers and gouge his eyes out. His spine prickled with the anticipation of her lethality.

“We really mustn’t make a habit of being apart for so long,” she told him quietly, when she finally pulled away to settle on her back. Corvus delicately traced the swollen plush of her lower lip, already missing their connection. “I was not beyond taking you in the office, despite the interruption, though that speaks volumes on our lack of common decency.”

Corvus’ forefinger trekked along the curve of her shoulder, following the dip of her chest to her breast. “I should have cut his head from his shoulders and had you anyway.” His fingertip ran the circumference of her areola and she took in a sharp breath. “I care little for decency.”

Proxima groaned when he replicated his motion again, the fondness understated by the sweetness of it, how gentle he was being when he hardly ever was before. “And I care little for your—oh—stalling—”

“Am I distracting you?” he asked, flicking her perked nipple with his tongue.

Proxima’s only answer was a groan, barely emitted but somehow like a sudden gunshot in the stillness of the night. It rattled his entire being. Taking in her sounds and her presence, and threatening to shake apart under the strength of her existence alone.