#ghosts of britain

Text

At any given moment Robin is operating on some fucking five dimensional philosophical mental acrobatics chess that others cannot even begin to grasp

351 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ghost of Banquo by Théodore Chassériau

#banquo#ghost#art#théodore chassériau#macbeth#shakespeare#william shakespere#banquet#ghosts#feast#spectre#phantom#king#phantoms#lord banquo#scotland#scottish#britain#british

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

now if you think about it, in l&co, the Problem wouldn’t be able to spread across the ocean to other landmasses, due to the waves/massive amounts of water. meaning it only exists on the island of Great Britain. and since there is little to no mention of other countries in the series, I always assumed that Great Britain became an isolationist nation during the 70s. diplomatic visits and trade must have become nonexistent…

…meaning that in l&co, Ireland is unified and ghost-free

#IRELANDDDD#but this was my biggest unanswered question about the l&co universe#how does great britain work as a country?? what is their relationship to the outside world??#we know mr/ms lockwood went on research expeditions to other countries but did they worry abt ghosts there too??#probably not#lockwood and co#missing lockwood and co hours#l&co#anthony lockwood#lucy carlyle#george karim#the screaming staircase

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiell Smith-Bynoe & Charlotte Ritchie

#kiell smith-bynoe#kiell smith bynoe#charlotte ritchie#bbc ghosts#rj: photoset#rj: glow up: britain's next make-up star#rj: kiell smith-bynoe#rj: charlotte ritchie#rj: 2023

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dode village was wiped out by plague, but her parish church survives

#Dode#Kent#Black Death#plague village#1349#mediaeval#British history#ghost village#parish church#rural britain#UK

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was delirious with a horrible fever and I was in a music studio being forced to help record the newest NIN Ghosts album. Trent Reznor wasn’t around for some reason and Atticus Ross was just lecturing me with his gangly ass sounding British accent.

#dream#text#March 27th 2023#fever#studio#music#recording#nin#nin ghosts#nine inch nails#trent reznor#atticus ros#british#britain#accent

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

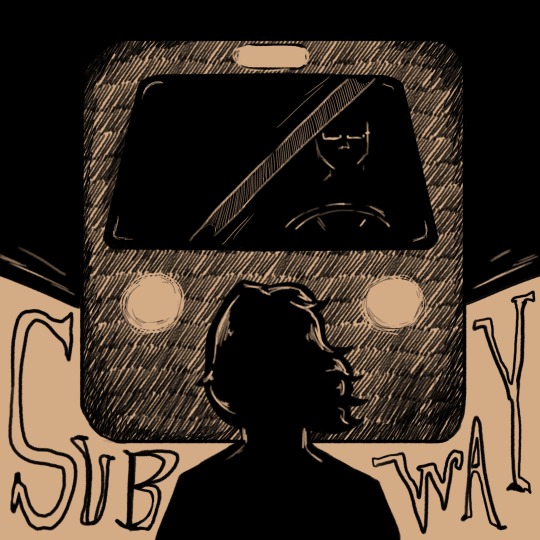

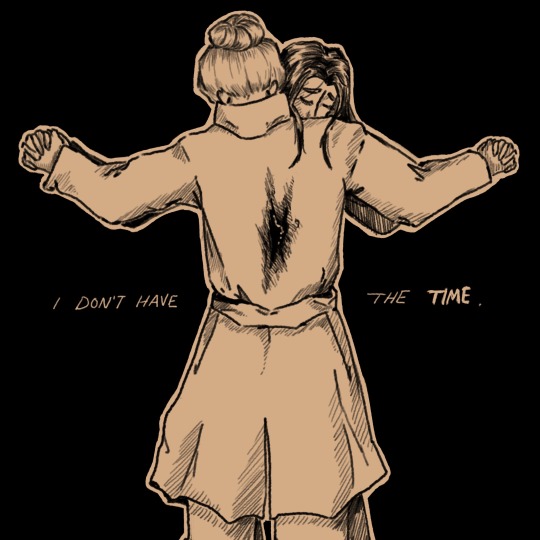

Just a few of my favorite inktober pieces I’ve done so far :)

I’m using my own prompts based off of ghost quartet

#julis art#illustration#inktober#ghost quartet#dave malloy#Britain ashford#gelsy bell#rose red#pearl white#usher#soldierose#great comet#digital art#October#art challenge#art prompts#scherazade#Halloween#ghosts

565 notes

·

View notes

Text

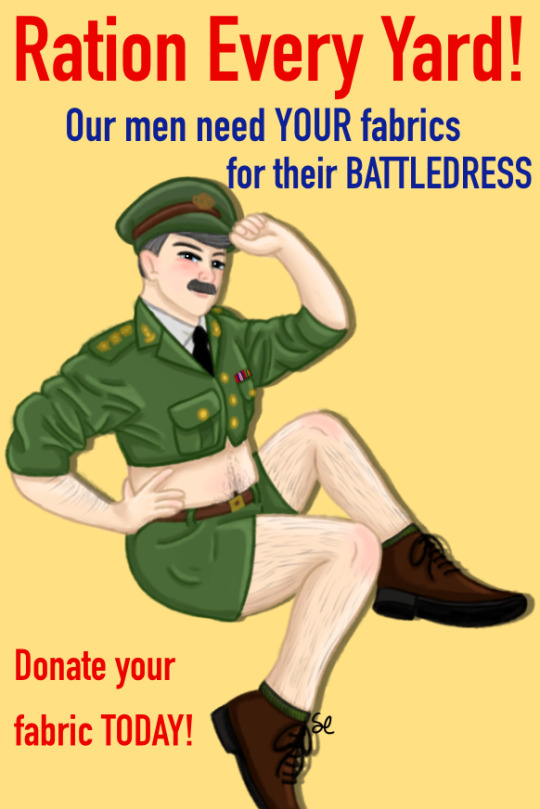

We wouldn’t want our men scantily clad on the battlefield, now would we?

Okay so what if I’m slightly addicted to making slutty war propaganda posters? What are you gonna do about it, huh?

The Captain: Making war cunty since 1939

#clothes rationing in britain was introduced on june 1 1941 for those who are curious#so don’t tell me I never taught you anything#I’m normal about him I promise#bbc ghosts#the captain#bbc ghosts fanart#my art

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elliott O'Donnell - Haunted Britain - Consul - 1963

#witches#phantom heads#occult#vintage#haunted britain#haunted#britain#consul books#vampires#evil ghosts#dangerous ghosts#ghosts#true stories#elliott o'donnell#1963

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The skeleton of King Richard the third. Found buried under what was once a church in Leicester England. The King died in the Battle of Bosworth 1485. The Kings remains had been lost to history until September 2012.

The remains of Richard III, the last English king killed in battle and last king of the House of York, were discovered within the site of the former Grey Friars Priory in Leicester, England, in September 2012. Following extensive anthropological and genetic testing, the remains were reinterred at Leicester Cathedral on 26 March 2015.

#King Richard the third#archaeology#Britain#UK#the lost king#history#goth#dark#skeleton#ghosts#spirits#moon#stars#crystals#space#Dark Aesthetic#victorian goth#Goth Girls

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is August 1854, and London is a city of scavengers. Just the names alone read now like some kind of exotic zoological catalogue: bone-pickers, rag-gatherers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers, shoremen. These were the London underclasses, at least a hundred thousand strong. So immense were their numbers that had the scavengers broken off and formed their own city, it would have been the fifth-largest in all of England. But the diversity and precision of their routines were more remarkable than their sheer number. Early risers strolling along the Thames would see the toshers wading through the muck of low tide, dressed almost comically in flowing velveteen coats, their oversized pockets filled with stray bits of copper recovered from the water's edge. The toshers walked with a lantern strapped to their chest to help them see in the predawn gloom, and carried an eight-foot-long pole that they used to test the ground in front of them, and to pull themselves out when they stumbled into a quagmire. The pole and the eerie glow of the lantern through the robes gave them the look of ragged wizards, scouring the foul river's edge for magic coins. Beside them fluttered the mud-larks, often children, dressed in tatters and content to scavenge all the waste that the toshers rejected as below their standards: lumps of coal, old wood, scraps of rope.

Above the river, in the streets of the city, the pure-finders eked out a living by collecting dog shit (colloquially called “pure”) while the bone-pickers foraged for carcasses of any stripe. Below ground, in the cramped but growing network of tunnels beneath London's streets, the sewer-hunters slogged through the flowing waste of the metropolis. Every few months, an unusually dense pocket of methane gas would be ignited by one of their kerosene lamps and the hapless soul would be incinerated twenty feet below ground, in a river of raw sewage.

The scavengers, in other words, lived in a world of excrement and death. Dickens began his last great novel, Our Mutual Friend, with a father-daughter team of toshers stumbling across a corpse floating in the Thames, whose coins they solemnly pocket. “What world does a dead man belong to?” the father asks rhetorically, when chided by a fellow tosher for stealing from a corpse. “'Tother world. What world does money belong to? This world.” Dickens' unspoken point is that the two worlds, the dead and the living, have begun to coexist in these marginal spaces. The bustling commerce of the great city has conjured up its opposite, a ghost class that somehow mimics the status markers and value calculations of the material world. Consider the haunting precision of the bone-pickers' daily routine, as captured in Henry Mayhew's pioneering 1844 work, London Labour and the London Poor:

It usually takes the bone-picker from seven to nine hours to go over his rounds, during which time he travels from 20 to 30 miles with a quarter to a half hundredweight on his back. In the summer he usually reaches home about eleven of the day, and in the winter about one or two. On his return home he proceeds to sort the contents of his bag. He separates the rags from the bones, and these again from the old metal (if he be luckly enough to have found any). He divides the rags into various lots, according as they are white or coloured; and if he have picked up any pieces of canvas or sacking, he makes these also into a separate parcel. When he has finished the sorting he takes his several lots to the ragshop or the marine-store dealers, and realizes upon them whatever they may be worth. For the white rags he gets from 2d. to 3d. per pound, according as they are clean or soiled. The white rags are very difficult to be found; they are mostly very dirty, and are therefore sold with the coloured ones at the rate of about 5 lbs. for 2d.

The homeless continue to haunt today's postindustrial cities, but they rarely display the professional clarity of the bone-picker's impromptu trade, for two primary reasons. First, minimum wages and government assistance are now substantial enough that it no longer makes economic sense to eke out a living as a scavenger. (Where wages remain depressed, scavenging remains a vital occupation; witness the perpendadores of Mexico City). The bone collector's trade has also declined because most modern cities possess elaborate systems for managing the waste generated by their inhabitants. (In fact, the closest American equivalent to the Victorian scavengers – the aluminium-can collectors you sometimes see hovering outside supermarkets – rely on precisely those waste-management systems for their paycheck.) But London in 1854 was a Victorian metropolis trying to make do with an Elizabethan public infrastructure. The city was vast even by today's standards, with two and a half million people crammed inside a thirty-mile circumference. But most of the techniques for managing that kind of population density that we now take for granted – recycling centers, public-health departments, safe sewage removal – hadn't been invented yet.

And so the city itself improvised a response – an unplanned, organic response, to be sure, but at the same time a response that was precisely contoured to the community's waste-removal needs. As the garbage and excrement grew, an underground market for refuse developed, with hooks into established trades. Specialists emerged, each dutifully carting goods to the appropriate site in the official market: the bone collectors selling their goods to the bone-boilers, the pure-finders selling their dog shit to tanners, who used the “pure” to rid their leather goods of the lime they had soaked in for weeks to remove animal hair. (A process widely considered to be, as one tanner put it, “the most disagreeable in the whole range of manufacture.”)

We're naturally inclined to consider these scavengers tragic figures, and to fulminate against a system that allowed so many thousands to eke out a living by foraging through human waste. In many ways, this is the correct response. (It was, to be sure, the response of the great crusaders of the age, among them Dickens and Mayhew.) But such social outrage should be accompanied by a measure of wonder and respect: without any central planner coordinating their actions, without any education at all, this itinerant underclass managed to conjure up an entire system for processing and sorting the waste generated by two million people. The great contribution usually ascribed to Mayhew's London Labour is simply his willingness to see and record the details of these impoverished lives. But just as valuable was the insight that came out of that bookkeeping, once he had run the numbers: far from being unproductive vagabonds, Mayhew discovered, these people were actually performing an essential function for their community. “The removal of the refuse of a large town,” he wrote, “is, perhaps, one of the most important of social operations.” And the scavengers of Victorian London weren't just getting rid of that refuse – they were recycling it.

— The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic - and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World (Steven Johnson)

#book quotes#steven johnson#the ghost map#the ghost map: the story of london's most terrifying epidemic - and how it changed science cities and the modern world#history#sanitation#waste management#recycling#economics#poverty#employment#labour#sociology#homelessness#welfare#authors#britain#victorian britain#england#london#thames#mudlarks#toshers#tanners#charles dickens#henry mayhew

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last Lockwood & Co book is in transit but it just occurred to me that if Lockwood said his parents were his first ghosts, that means his sister died afterward. So while he was still a preteen his parents died, he saw and possibly fought their revenants, his sister died, he destroyed the ghost that killed her, and then just..... kept living in their family's empty house on his own. No wonder he is so deeply unwell.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idk you guys, this message from the palace is pretty cryptic🤨

#ghost#the band ghost#papa emeritus#uk#britain#royalty#monarchy#the royal family#kate middleton#princess kate

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel so dumb how did I just realize robin and Humphrey are played by the same guy

#i was resding the credits on my rewatch and noticed it#dont come for me ive never watched anything from these people before#i know they're really well known in Britain#bbc ghosts

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know why but I keep having a Cunk fanfic about a ghost in a museum finds this weird funny human???

Help me

#philomena cunk#cunk on earth#cunk on britain#cunk on shakespeare#ghost#I dont know ????#fanfic#fanfiction

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

May I offer you a Julian Fawcett in these trying times?

#yes I am aware of what the ✌️ sign means in britain and personally I think it makes the whole thing better#it took me far too long to get the hand on the hip right holy shit lmao#bbc ghosts#julian fawcett#bbc ghosts fanart#my art

59 notes

·

View notes