#walker percy

Text

"Earthshaker, stormbringer, father of horses. Hail Perseus Jackson, Son of the Sea God." 🌊

#i guess the key for learning how to do backgrounds is not drawing for over four months cause idek how i did that#percy jackson#pjo#pjo tv#percy jackson and the olympians#walker scobell#walker percy#percy series#pjo tv show#percy jackson tv show#fanart#digital art#art

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you guys think they shot all the Camp Half-Blood scenes together???? Because if they did, Percy’s gonna shrink into a babier baby again in the next episode 😭😭😭

#walker grew so much in 7 episodes#percy jackson disney+#percy jackson show#percy jackon and the olympians#percy jackson#percy jackson fandom#pjo#pjo ep 8#pjo fandom#pjo tv adaptation#pjo tv#pjo tv show#pjo tv series#pjo series#pjo disney+#disney pjo#walker percy#walker scobell

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

What needs to be discharged is the intolerable tenderness of the past, the past gone and grieved over and never made sense of. Music ransoms us from the past, declares an amnesty, brackets and sets aside the old puzzles. Sing a new song. Start a new life, get a girl, look into her shadowy eyes, smile.

Walker Percy, Love in the Ruins

#walker percy#love in the ruins#dark academia#spilled words#light academia#grief#words#dark aesthetic#romantic academia#quoteoftheday#love quotes#quotes#oldschoolromantics

35 notes

·

View notes

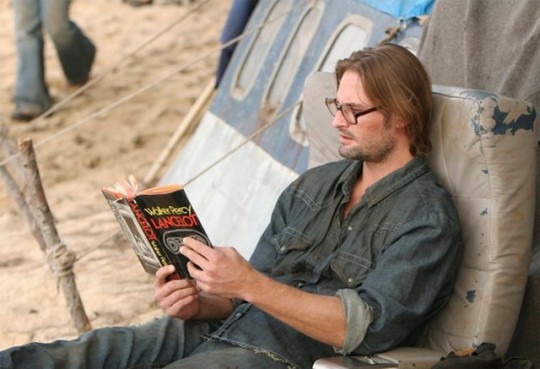

Photo

Lost S02E15 (Maternity Leave)

Book title: Lancelot (1977) by Walker Percy

#lost#lost season 2#maternity leave#walker percy#lancelot#books in tv shows#josh holloway#james sawyer ford#american literature

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ssh, stop fussing. I'm just plaiting your hair.

This is the second chapter of my oneshot series on ao3. I might post the first chapter on tumblr if people enjoy this one. Anyway I hope you enjoy and if you have any requests or if you just want to chat, please don't hesitate.

As Percy looked around, he thought about all that had happened over the last few weeks, between finding out his dad was a god, going on a life-threatening quest, and everything that had happened with Luke, he couldn’t remember the last time he’d been truly relaxed. Until this moment there had always been some lingering feeling of doubt or fear. It was ironic that the first time he properly forgot about everything was the night before the last day of summer.

Due to the three of them parting ways, Percy, Annabeth and Grover had decided to spend the evening in the Poseidon cabin. Even in the moment Percy wasn’t sure what they were talking about exactly but all he knew was that it had nothing to do with Luke or their Quest and he had never laughed more than he did that night.

None of them had talked about it since that night, other than the mandatory meetings with Chiron that Percy and Annabeth had. It had felt like a bit of a taboo, like if they said it, then it would become real. So they tip-toed around it, creating their own unspoken rule. But again, for the first time none of them felt like they had to think about what they were saying, because at that moment they were simply Percy, Annabeth and Grover. Not heroes, not demigods, not saviors of Olympus. Just friends. Just kids.

It was about an hour and a half past curfew and they had all decided that it would be easier if Annabeth and Gover just stayed with Percy in the Poseidon cabin instead of trying to sneak past the harpies. They had shoved two of the bunk beds together and were lying curled up, Percy and Annabeth at the top with Grover at their feet.

Grover had fallen asleep a while ago and showed no signs of waking up, if the low snores were anything to go by. The other two lay basking in the warmth of their friendship, and the feeling of peace.

Percy’s eyes were drooping and Annabeth had yawned three times in the last five minutes so it wouldn’t be long until they nodded off as well. But for now they fought to stay awake, to enjoy each other's company for just a moment longer. No words were spoken because no words were necessary. Despite only having known each other for a month, the two had an unexplainable connection, knowing what the other was thinking with barely so much as a glance.

Annabeth lay her head on Percy’s shoulder, an action that bordered the line between exhaustion and affection. He returned the gesture, feeling her silky, woven braids upon his cheek and the warm puff of her breath against his neck.

Percy was brought back to his senses by the tug of her fingers in his hair, her hand running through his loose, messy curls.

“What are you doing?”

“Your hair is a really pretty colour, reminds me of sand,” She ignored his question and her hand moved further towards the front of his head. “My dad would call it the colour of champagne.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen any.” Percy’s reply was dreary, Annabeth’s soft touch making him even sleepier than he was before.

For some reason his response surprised Annabeth as she twisted to look at him. “Not even on New Year's Eve or anything?” She was weirdly shocked about this, Percy thought.

“It was too expensive, the only money my family spent on alcohol was what my stepdad spent on beer.” Annabeth rolled her eyes at the last bit and it made Percy feel oddly happy that she knew about Gabe, more than Grover did at least. She was one of the only people that Percy didn’t keep any secrets from.

Fifteen minutes later Percy could tell that Annabeth was mere minutes away from sleep, but still, her fingers were intertwined with his hair, pulling and tugging in a way that Percy was unfamiliar with. If he was being honest she was pulling a little too hard for his liking but it wasn’t until a particularly harsh tug that he lazily tried to push her hand away. She kept going anyway, ignoring his tired attempt to stop her.

A couple of minutes later there was another small stab of pain and this time Percy tried to pull his head away.

“What’re you doing?” Percy sleepily grumbled.

“Ssh, stop fussing Seaweed Brain. I’m just plaiting your hair.”

When Percy awoke the next morning he felt the small braid tickling the back of his neck and a blush rising to his cheeks as he touched the back of his neck. Annabeth still sounded asleep beside him.

#percabeth#percabeth fanfic#percy x annabeth#percy jackon and the olympians#walker percy#leahbeth#percy jackson#annabeth chase#percy and annabeth#pjo tv show#pjo fanfic

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Imagine that you are a member of a tour visiting Greece. The group goes to the Parthenon. It is a bore. Few people even bother to look—it looked better in the brochure. So people take half a look, mostly take pic-tures, remark on the serious erosion by acid rain. You are puzzled. Why should one of the glories and fonts of Western civilization, viewed under pleasant conditions—good weather, good hotel room, good food, good guide—be a bore?

Now imagine under what set of circumstances a viewing of the Parthenon would not be a bore. For example, you are a NATO colonel defending Greece against a Soviet assault. You are in a bunker in downtown Athens, binoculars propped on sandbags. It is dawn. A medium-range missile attack is under way. Half a million Greeks are dead. Two missiles bracket the Parthenon. The next will surely be a hit. Between columns of smoke, a ray of golden light catches the portico.

Are you bored? Can you see the Parthenon?”

— Walker Percy: Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We love those who know the worst of us and don’t turn their faces away."

Walker Percy, author (28th May 1916-1990)

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

... the poet's perspective: "what matters is not the human pain or joy at all but, rather, the play of shadow and light on a live body, the harmony of trifles assembled on this particular day, at this particular moment, in a unique and imitable way."

Whilst this stand distinctly echoes Bergson's privileging of an artistic vision, whereby 'man glimpses reality through the film of familiarity and conventionality that obscures it', it also deploys the Russian Formalist process of ostranenie, or 'making strange', whereby art serves to reveal the aesthetic and hyper-real qualities of ordinary objects by disrupting habitual modes of visualization and confounding perceptual expectations. Nabokov's emphasis on 'making strange' is also suggestive of the presence of 'other' worlds, or an 'anterior reality', reminiscent of the Russian Symbolist impulse, which sought to reveal a transcendent essence that lay beyond 'the concrete presence of an object'.

Barbara Wyllie, Vladimir Nabokov (2010) | Chapter 1. Hyper-reality underlying/behind/beyond/alongside the mundane. The eternal and transcendent in the aesthetic. On "other worlds", they go on to highlight Nabokov's use of reflections in water and glass. Fits well with my concurrent reading of Walker Percy's The Moviegoer: Binx being abstracted from doing research by motes in sunlight.

#vladimir nabokov#literary analysis#writing#writing technique#symbolism#reality#archreality#the moviegoer#walker percy

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walker Percy statue in Bogue Falaya Park, Covington, Louisiana

“A Talk with Walker Percy

Zoltán Abádi-Nagy

The Southern Literary Journal, 6 (Fall 1973)

Q: You maintain that perhaps the best way of writing about America in general is to write with authenticity about one particular part of America. By extension this means that, likewise, your attitude and reaction toward philosophical questions of universal human importance— toward the question of the human predicament, to use the term of your philosophy—will be that of an American. Is that correct?

A: I think that is true. My novels have more a European origin than American. They are so-called philosophical novels which is probably a bad word. But you know that the first half of your question is quite true. The greatest exponent of this was Faulkner who concentrated on a small village in Mississippi. It is true that I am interested in philosophical, religious issues and in my novels I use the particular in order to get at the general issues. For example, The Moviegoer is about New Orleans, one part in New Orleans, a young man in New Orleans. The conflict is a hidden ideological conflict involving, on the one hand, what I call Southern stoicism. I have an uncle whose hero was Marcus Aurelius. The other ideology is Christian Catholic. The third: the protagonist is in an existentialist predicament, alienated from both cultures.

Q: What in your view is it in America that makes an existentialist today? What facets of the American intellectual climate, of the American existence in general, are favorable to existentialist thinking?

A: I think in America the revolt is less overtly philosophical. It is a feeling of alienation from American suburban life, the suburb, the country-club, the business community. There is a difference between my protagonists and the so-called counter culture. Many young people revolt in a purely negative way, oppose their parents' culture; whereas the leading characters in my books are much more consciously embarked on some sort of search. I am telling you that because I would not want you to confuse the characters of the counter culture with my characters. One of their beliefs is that the American scene is phony, and their revolt is to seek authenticity in drugs, sex, or in a different kind of communal existence. The characters in my books are embarked on a much more serious search for meaning.

(…)

Q: Your view of life in your literary works is very close to the absurdist view, but the term 'absurd' and the whole Camus terminology hardly ever appears in your philosophical essays. Does this coincide with your preference for Marcel's Catholic version of existentialism as opposed to the post-Christian character of the meaninglessness of Sisyphus' situation?

A: Yes, that is correct. I identity philosophically with people like Gabriel Marcel. And if you want to call me a philosophical Catholic existentialist, I would not object, although the term existentialist is being so abused now that it means very little. But stylistically mainly two French novels affected me: Sartre's La Nausée and Camus' L'etranger. I agree with their novelistic technique but not with their absurdist view.

Q: Is not your third novel, Love in the Ruins, with its Layer I and Layer II—the social self and the inner, individual self—a comic attempt to solve Marcel's dilemma about this separation?

A: You are right. This is a comic device to get at what, ever since Kierkegaard, has been called the modern sickness: the disease of abstraction. I think in the novel Dr. More calls the illness angelism-bestialism. There is nothing new about this. It had been mentioned by many writers in various ways. Pascal said that man is both not quite as high as an angel and not quite as low as a beast. So Dr. More is aware of this schism in consciousness. He talks about the modem mind which, as he sees it, abstracts from the world, from itself, and manages to lose touch with reality.

(…)

Q: Much of it, especially in Love in the Ruins, seems to be a social problem viewed from an existentialist viewpoint of the human predicament. Actually, this is a kind of movement I notice in your works: an increasing awareness of how much the social predicament has to do with the human predicament. If Binx in The Moviegoer was suffocating in an adverse climate of malaise which was a social phenomenon, he was not much aware of its having to do with society; he was not concentrating on things like the social self as later Dr. More is in Love in the Ruins. Was this an intentional change on your part or was the movement towards the concept of malaise as a social product spontaneously developing through the inner logics of these relations?

A: It was a conscious change. Love in the Ruins was intended to take a certain point of view of Dr. More's and from it to see the social and political situation in America. Unlike Binx, whose difficulties were more personal, Dr. More finds himself involved in contemporary issues: the black-white conflict and the problem of science, scientific technology which is treated as a sociological reality today. Both the good and bad of it. I really use this to say what I wanted to say about contemporary issues. About polarization; there are half a dozen of them: black-white, North-South, young-old, affluent-poor, etc. And do not forget that at the end of Love in the Ruins there is a suggestion of a new community, new reconciliation. It has been called a pessimistic novel but I do not think it is. A renewed community is suggested. The suggestion is in the last scene which takes place in a midnight mass between a Christmas Saturday and Sunday. The Catholics, the Jews come to the midnight mass, also the unbelievers in the same community. The great difference between Dr. More and the other heroes is that Dr. More has no philosophical problems. He knows what he believes.

Q: Is it a religious reconciliation then?

A: Yes, that is the case. This was meant for Southerners in particular and for Americans in general.

Q: Binx in The Moviegoer and Barrett in The Last Gentleman do not seem to have the set of positive values needed for absurd creation as conceived by Camus to create their own meaning in meaninglessness. Is this connected with your idea of the aesthetic reversion of alienation, i.e. by communicating their alienation they get rid of it?

A: Yes, there is something there. In the case of Binx it is left open. The ending is ambiguous. It is not made clear whether he returns to his mother's religion or takes on his aunt's stoic values. But he does manage to make a life by going into medicine, helping Kate by marrying her. I suppose Sartre and Camus would look on this as a bourgeois retreat he had made.

Q: How do you look on it?

A: Well, I think he probably . . . as a matter of fact the last two pages of The Moviegoer were meant as a conscious salute to Dostoevski, in particular to the last few pages of The Brothers Karamazov. Very few people notice this.

Q: To me the most striking difference between the European and the American absurdist view is the ability of the American to couple the grim seriousness with hilarious humor, to turn apocalypse into farce. In comparison, Beckett, for all the grim comedy which is there, is a sheer tragic affair. Can you think of some explanation for this?

A: That is a good question and I can only quote Kierkegaard, who said something that astounded me and that I did not understand for a long time. He spoke of the three stages of existence: the aesthetic, the ethical, the religious. When you pass the first two you find yourself in an existentialist predicament which can be open to the religious or the absurd. He equated religion with the absurdity. He called it the leap into the absurd. But what he said and was puzzling to me was that, after the first two, the closest thing to the third stage is humor. I thought about that for a long time. I cannot explain it except I know it is true.

There is another explanation, too, of course. Hemingway once said: all good American novels come from one novel written by a man named Mark Twain. With Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain established the tradition of this very broad and satirical humor. I think the American writer finds it natural to use humor both in his satire and in describing even the worst predicament of his main character. In this country we call it black humor: disproportion between the gravity of the character's predicament and the hilarity of the humor with which it is treated. Vonnegut uses this a good deal.

Q: Richard B. Hauck in A Cheerful Nihilism points out how Franklin, Melville, Twain, Faulkner have shown that the response to the absurd sense can be laughter. At one point Binx becomes aware of the similarity of his predicament to that of the Jews. "I accept my exile," he says. Whether we accept this as his affirmation of life in its absurdity or not, what follows is comedy. Could you agree that this comedy as well as Franklin's, Melville's and the others' could be regarded as the absurd creation of the American Sisyphus as opposed to the serious defiance of Camus' king?

A: I do not know if I would go that far. It may be much simpler. There is an old American saying that the one way to stop crying is to laugh. Binx says, "I feel more homeless than the Jews." Between him and the Camus and Sartrean heroes of the absurd there is a difference. Camus would probably say the hero has to create his own values whether absurd or not, whereas Binx does not accept that the world is absurd; so he embarks on a search. So to him the Jews are a sign. I think he said, "Lately when I see a Jew on a street I am amazed nobody finds it remarkable. But I find it remarkable. But to me it is like seeing Friday's footprint in the beach. " Of course, he is not sure what it is the sign of. Sartre's Roquentin in La Nausée or Camus' Meursault in L'etranger would not find anything remarkable about a Jew, they would not be interested in him.

Q: In your philosophical essay, "The Man on the Train," you stress the speakability of the commuter's alienation and the fact that the commuter rejoices in this speakability. We can probably add: laughability. Incidentally, you do mention in the same article how Kafka and his friends were roaring with laughter when Kafka read his work aloud to them. Again if we had the answer to how alienation can become a laughing-matter, we would have the key to much of what is recently called black humor.

A: I think you are right. In "The Man on the Train" I was talking about the aesthetic reversal: the alienated commuter feeling totally alienated when reading a book about alienation feels better because there is a communication between himself and the writer.

Q: The forms of alienation you are concerned with in your fiction are all results of the objectification, mechanization of the subjective. Does not this view meet somewhere at a point with Bergson's view of the comic as the mechanical manifested in a living human being?

A: It sounds reasonable but I cannot enlarge on that. I am not familiar enough with Bergson. But to your previous question. Let me finish. It is the first time it occurs to me. You brought it up. Maybe, a person like Sartre spent a lot of time writing in a café about alienated people, the lack of communication, etc., and yet, in doing so, he became the least alienated person in France. By writing he performs a superb act of communication for which he has many readers. So you have a complete reversal. He writes about one thing and reverses it through communication. Here we have the American writer locked in his alienation. But I can envision the American writer getting onto it; by seeing the possibility of communication, exhilaration, his alienation becomes speakable. There can be a tremendous release from that. I have never thought of this before. Nobody knows what is going on when you communicate the unspeakable. This all-important step from unspeakability to speakability is such a triumph that in his own exhilaration the American writer finds it natural to use the Mark Twain tradition of the funny, the humorous.

(…)

Q: Religion reminds me of another tendency I notice in your novels from Binx through Dr. Sutter to Dr. More: the scientist Dr. Percy showing in the novels much more than the Catholic. How would you comment on your religious presence in the philosophical essays the—whole idea of the islander opening all those bottles hoping for 'the message'—and on the absence of practical religion from the novels. I know that religion is there as a theme but with no commitment of the writer in any direction.

A: Well, that is very simple. James Joyce said that an artist must be above all things cunning and guileful and must use every trick in the bag to achieve his purpose. In my view the language of religion, the very words themselves, are almost bankrupt. If you are writing a technical article on philosophy you can use the correct word for the correct meaning. But writing a novel is something different. In my view you have to be wary of using words like 'religion,' 'God,' 'sin,' 'salvation,' ‘baptism' because the words are almost worn out. The themes have to be implicit rather than explicit. I think I am conscious of the danger of the novelist trying to draw a moral. What Kierkegaard called 'edifying' would be a fatal step for a novelist. But the novelist cannot help but be informed by his own anthropology, the nature of man. In this respect I use 'anthropology' in the European philosophical sense. Camus, Sartre, Marcel in this sense can all be called anthropologists. In America people think of somebody going out and measuring skulls, digging up ruins when you mention 'an-thropology.' I call mine philosophical anthropology. I am not talking about God. I am not a theologian.

Q: What I meant was not the question of style and technique explicit or implicit but the religious commitment which is there in your philosophical writings but absent from the novels or always left open at best.

A: As it should be left open in the novel.

(…)

Q: None of the main characters in your three books have problems in making a living. Binx is a successful broker, Barrett inherited from his father, Dr. More from his wife. Do you do this to contrast seeming affluence with emptiness under it?

A: I had not thought about it. Maybe so, maybe also to use it as a device to reinforce the rootlessness. After all if these fellows had been day-laborers working very hard they would have had no time for various speculations.

Q: Does that mean that existentialism has no comment on those who are without these economic means and consequently perhaps in a much more serious predicament—because they have no time for speculations?

A: To that Marx would have an answer, Henry Ford would have an answer, Chaplin would have another, etc. Marx invented the term alienation. . .

Q: He reinterpreted an older concept, he discovered a new explanation for alienation.

A: But it is now transferred to a different class of society in Sartre, Camus. These desperately alienated people are members of a rootless bourgeoisie, not the exploited proletariat.

Q: Your novels demonstrate that to many questions affluence is no answer. Danger of life and the saving of lives often figure in your work as in many other black humorists', too. One can think of Barth's The Floating Opera, The End of the Road, Giles Goat-Boy, Vonnegut's The Sirens of Titan, Mother Night, Cat's Cradle and others, Kesey's two novels, Pynchon's V., Heller's Catch-22 and We Bombed in New Haven, etc. Do you think that this or a similar event of great moment in one's life is necessary to awaken the existentialist hero to his absurd situation and that this somehow is needed to shock him into the feeling of necessity for 'intersubjectivity' and shared consciousness as an escape from 'everydayness'?

A: I think that touches on a subject I have been interested in for a long time—a theme I use in all my novels: the recovery of the real through ordeal. It is some traumatic experience—war, Dr. More's attempted suicide—in each case. You have the paradox here that near death you can become aware of what is real. I did not invent this. Prince Andrey lying at the Battle of Borodino and looking at the clouds, makes a discovery: he sees the clouds for the first time in his life. So Binx is the opposite of Prince Andrey: he watches the dung-beetle crawling three inches from his nose.

Q: Correct me if I overinterpret the difference but now that you make this comparison it occurs to me that perhaps there is some irony here in the way it is an opening up of vision for Andrey towards the clouds, the sky, some magnificence suggested by these, and in the way Binx zooms down on an ugly little dung-beetle.

A: Maybe there is a little twist there. But the point is that a little creature as the dung-beetle is just as valuable as a cloud.

(…)

Q: Ordeal is one existentialist solution to escape from the malaise. How effective do you think the others, rotation and repetition, can be? Is it possible that their effect can be more than temporary?

A: To use Kierkegaard's term, they are simply aesthetic relief, therefore temporary.

Q: Friedman says that distortion can be found on the front page of any newspaper in America today. It is not the black humorist who distorts; life is distorted. Does everyday American reality stir you to write with similar directness? I ask this because once in an interview you appreciated the way Dostoevski was stirred to writing by a news item in a daily paper and because once in connection with Faulkner and Eudora Welty you referred to the social involvement of the writer as useful because social likes and dislikes, you said, can be the passion and energy you write from.

A: I see what Friedman means. Right. The danger with newspapers and TV is that it is all trivial. You remember in Camus' The Fall: we spend our lifetime "fornicating and reading the newspapers.” I think the danger is that you can spend your life reading the New York Times and never get below the surface of current events; whereas in Dostoevski's case—The Possessed—the whole was inspired by a news story in a Russian newspaper. I would contrast the inveterate newspaper reader and TV watcher who watches and watches and nothing happens—he is formed by the media. Dostoevski reads one news story, gets angry and this triggers a creative process.

Q: Intersubjectivity is an escape for Binx from everydayness and the other forms of the malaise, he is certainly not formed by the media. But are his aunt's values cars, a nice home, university degree—somehow recreated through intersubjectivity so that he can go back to these formerly rejected values?

A: Yes, sure. The question is, how much? And whether he did not go a good deal beyond intersubjectivity when he regained his mother's religion. Binx says at the end that what he believes is not the reader's business, he cuts the reader loose, refuses to be edifying. This is Kierkegaard going back to Socrates, "I want no disciples."

Q: But in the next paragraph he says, "Further: I am a member of my mother's family after all and so naturally shy away from the subject of religion (a peculiar word this in the first place, religion; it is something to be suspicious of)." This means, it seems to me, that Binx definitely objects to being edifying, especially in a religious way.

A: Yes, if you like.

(…)

Q: I wonder why it is necessary to bring the mental sickness of these characters into such a sharp focus? Is it to perplex the world with the old enigma: are these sick people in a normal world or normal people in a sick world? Or is it the interest of the medical doctor? Or both?

A: It is partly therapeutic, medical interest but also goes deeper than that. The view of Pascal and some others who were interested in the human condition was that there is something wrong with mankind. So it is always undecided in my novels. This is the main question of the novels. Here is a hero who is afflicted, shows malaise, dislocation, and he is surrounded by apparently happy and sane people, particularly Dr. More, who lives in Paradise Estates. So who is crazy, the people apparently happy or those radically dislocated characters?

(…)

Q: Although I know you have been frequently asked about the position of the writer in the South, I would like to ask you to summarize your view on this question for the Hungarian reader for whom this talk is primarily intended and for whom your view of the writer in the South will be a novelty.

A: The position of the Southern writer now, as opposed to thirty years ago when Faulkner was writing, is more and more on a level with other writers' in other parts of the country. In other words the United States is becoming more and more homogenized. America is becoming more alike. Towns in the South lose their distinctive character. And yet, I think, in spite of this, there remains and probably there will remain a unique community in the South between black and white, so that there is much more communication, strangely enough, between middle-class white and black people in the South than there is between intellectual black and white in the North. In the South they have lived in physically intimate terms for 300 years. And whatever might have been the evils of this system, there still exists a strong historical basis of communication. I think it will continue to exist.

Q: Speaking about America, it occurs to me to ask you at this point if you have ever thought of rotation in historical aspect? Of America as a historical experience in rotation? What the settlers did coming from Europe, or the pioneers did going west was, it seems to me, as exactly zone-crossing as anything in the existentialist meaning of the term—even though the term came much later. If I may go one step further, how can you comment on the effectiveness of this rotation in the light of what you say on the first pages of Love in the Ruins: "our beloved old U.S.A. is in a bad way." And later, "now the blessing or the luck is over, the machinery clanks, the chain catches hold . . .”?

A: I did not think of rotation in an historical aspect. But if rotation is temporary it should run out. That makes it tough. There are more suicides in San Francisco today than in other cities; that is why the rotation has run out, which may or may not be significant. That is what Kierkegaard calls aesthetic damnation—living by rotation.”

#percy#walker percy#existentialism#camus#albert camus#absurdism#marcel#gabriel marcel#pascal#dostoyevski#kierkegaard#soren kierkegaard#faulkner#literature#southern literature#philosophy#bogue falaya#covington#louisiana

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books acquired, 26 Jan. 2024

Last Friday, I drove across a bridge to a library on the other side of the city for a Friends of the Library sale. I was hoping for a nice leisurely afternoon browse, figured I’d find a few titles worth my efforts, and I’d fill out the 10 dollar brown paper grocery bag with books I could trade for store credit elsewhere. I ended up filling the bag almost immediately, mostly with heavy hardbacks,…

View On WordPress

#Books Acquired#Don DeLillo#Jeanette Winterson#Jesse Ball#John Barth#Lawrence Ferlinghetti#Leni Zumas#Raymond Carver#Robert Coover#Salem Kirban#Sven Birkert#Thomas S. Klise#Walker Percy

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: the Lamb at the Foot of the Cross, Flanked by Two Angels; The Calling of Saint John with the Enthroned Christ flanked by Angels and a Man Holding a Book (Spanish, c 1180). Illustrated Beatus manuscripts bring to life an extraordinary vision of the end of the world, as recorded by Saint John in the Apocalypse (Book of Revelation) and filtered through the lens of Beatus of Liébana, an eighth-century Asturian monk. These manuscripts are unique to medieval Spain and a testament to the artistry and intellectual milieu of monastic culture there. The leaf shown here comes from a manuscript that was disassembled in the 1870s.

This frontispiece image depicts a lamb (an image commonly associated with Christ) tormented by the spear and sponge used against Christ during the Passion. The alpha and omega symbols hanging from the cross refer to a passage from the Apocalypse: "I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, saith the Lord God, who is, and who was, and who is to come, the Almighty" (Apoc. 1:8)

[Robert Scott Horton]

* * * *

"This life is too much trouble, far too strange, to arrive at the end of it and then to be asked what you make of it and have to answer, ‘Scientific humanism." That won’t do. A poor show. Life is a mystery, love is a delight. Therefore I take it as axiomatic that one should settle for nothing less than the infinite mystery and the infinite delight, i.e. God. In fact, I demand it. I refuse to settle for anything less."

—Walker Percy, from Questions They Never Asked Me

(Lord John Press, 1979)

[alive on all channels]

#Beatus Manuscript#Lamb at the Foot of the Cross#Illustration#Scott horton#Alive On All Channels#Walker Percy#quotes#theology#mystery#religious art

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

some sort of moodboard

The Guy Who Didn't Like Musicals // The Dead Letter Office of Somewhere, Ohio; Episode 9 ( @somewhereohio ) // The Guy Who Didn't Like Musicals // Critical Role; Campaign 2, Episode 103 // The Dead Letter Office of Somewhere, Ohio; Episode 5 // Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book by Walker Percy // Teen Wolf; Season 6, Episode 1 // The Dead Letter Office of Somewhere, Ohio; Episode 11 // x from @neurotypical-karen // Brenna Yovanoff

#listen i've been feeling some type of way lately#and it's only partially dlo's fault#ramble#the guy who didn't like musicals#dead letter office of somewhere ohio#critical role#walker percy#teen wolf#neurotypical-karen#brenna yovenoff#quotes#dlo spoilers#moodboard#podcast things

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the 2024 American Climate Leadership Awards for High School Students now: https://youtu.be/5C-bb9PoRLc

The recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by student climate leaders! Join Aishah-Nyeta Brown & Jerome Foster II and be inspired by student climate leaders as we recognize the High School Student finalists. Watch now to find out which student received the $25,000 grand prize and top recognition!

#ACLA24#ACLA24HighSchoolStudents#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental education#environmental justice#environmental protection#environmental health#high school students#high school#youth#youth of america#school

6K notes

·

View notes

Quote

Comes the longing and it has to do with being fifteen and fifty and with the winter sun striking down into a brickyard and on clapboard walls rounded off with old hard blistered paint and across a doorsill onto linoleum. Desire has a smell: of cold linoleum and gas heat and the sour piebald bark of crepe myrtle.

Walker Percy, Love in the Ruins (Picador USA; Sept. 1999) (Via Whiskey River)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRST FANART OF THE CAST

Colour version below

@pjo-hoo-toa-freakazoid

Analysis of the art Below Because i wanted to analyse it idk

I was debating colour, and then i couldn’t find one of my pens that i needed, and i couldn’t draw online because sometimes thats not accecable to me.

I was debating colour, and then i couldn’t find one of my pens that i needed, and i couldn’t draw online because sometimes thats not accecable to me.

but i did end up with Colour. AND. Annabeth turned out pretty great for very rough penmanship and a few minutes of colour. WE are going to ignore percy.

#but i really wanted to draw this scene#ill draw grover soon as well.#percy jackson fanart#percy jackson casting#honesstky i love the castig so much idk its the energy im getting from all three of them#annabeth chase#leah is our annabeth#walker percy#my art#quick sketch#not digital

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In spite of great scientific and technological advances, man has not the faintest idea of who he is or what he is doing.“

-Walker Percy

4 notes

·

View notes