#iran and greece

Text

youtube

This epic song was made by the Iranian composer and musician, Farya Faraji! It captures the medieval Balkan style extremely well, and he sings in Greek and Old Church Slavonic (to represent the Bulgarian side)! Thank you, Farya Faraji, for your great cultural immersion!

This composition is about emperor Basil II Porphyrogennetos, “the Purple-born”, nicknamed the Bulgar Slayer (Boulgaroktónos). This nickname was earned after his conflict and annihilation of the First Bulgarian Empire, the principal European foe of the Eastern Romans during that era. A proficient statesman, the Empire flourished in many aspects during his reign, and his legacy is one of a national hero in Greece, whilst being despised among the Bulgarians.

Farya Faraji explains:

Musically, I wanted this track to reflect both Bulgarian and Greek sensibilities, and the best place for that was Thracian music—a shared cultural style overlapping both Greek and Bulgarian music. This geographical style of music, defined among other things by the usage of the gaida bagpipe to provide dance tunes also fits the geographical area where many of the confrontations between the two empires occurred, and also matches the regional origin of Basil’s dynasty, which originated from Thrace. The gaida bagpipe in this piece fulfills a dual Greek-Bulgarian role as it is used virtually identically on both sides of Thrace.

(see more of his explanations in the piece's description on YouTube)

#vasileios voulgaroktonos#Farya Faraji#iran and greece#greek music#thrace#bulgaria#bulgarian history#greek history#Youtube

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

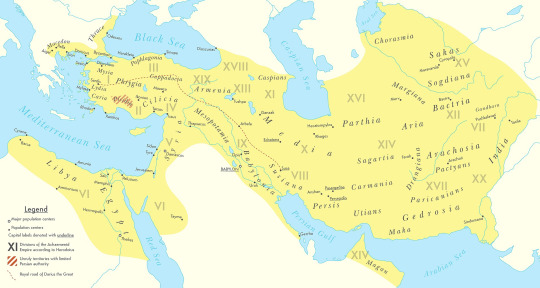

Countries that are no more: Achaemenid Empire (550BC-330BC)

It was not the first empire of Iranian peoples, but it arose as probably the greatest in terms of influence and became the measure by which all subsequent Iranian empires tended to compare themselves and its influence on culture, government & civil infrastructure would influence others beyond the span of its territory and the span of time. This is the Achaemenid Empire.

Name: In Old Persian it was known as Xšāça or the "The Kingdom or the Empire", it was named the Achaemenid Empire by later historians. Named after the ruling dynasty established by its founder Cyrus the Great who cited the name of his ancestor Haxāmaniš or Achaemenes in Greek as progenitor of the dynasty. It is sometimes also referred to as the First Persian Empire. The Greeks simply referred to it as Persia, the name which stuck for the geographic area of the Iranian plateau well into the modern era.

Language: Old Persian & Aramaic were the official languages. With Old Persian being an Iranian language that was the dynastic language of the Achaemenid ruling dynasty and the language of the Persians, an Iranian people who settled in what is now the southwestern Iranian plateau or southwest Iran circa 1,000 BC. Aramaic was a Semitic language that was the common and administrative language of the prior Neo-Assyrian & Neo-Babylonian Empires which centered in Mesopotamia or modern Iraq, Syria & Anatolian Turkey. After the Persian conquest of Babylon, the use of Aramaic remained the common tongue within the Mesopotamian regions of the empire, eventually becoming a lingua franca across the land. As the empire spread over a vast area and became increasingly multiethnic & multicultural, it absorbed many other languages among its subject peoples. These included the Semitic languages Akkadian, Phoenician & Hebrew. The Iranian language of Median among other regional Iranian languages (Sogdian, Bactrian etc). Various Anatolian languages, Elamite, Thracian & Greek among others.

Territory: 5.5 million kilometers squared or 2.1 million square miles at its peak circa 500BC. The Achaemenid Empire spanned from southern Europe in the Balkans (Greece, Bulgaria, European Turkey) & northwest Africa (Egypt, Libya & Sudan) in the west to its eastern stretches in the Indus Valley (Pakistan) to parts of Central Asia in the northeast. It was centered firstly in the Iranian Plateau (Iran) but also held capitals in Mesopotamia (Iraq). Territory was also found in parts of the Arabian Peninsula & the Caucausus Mountains.

Symbols & Mottos: The Shahbaz or Derafsh Shahbaz was used as the standard of Cyrus the Great, founder of the empire. It depicts a bird of prey, typically believed to be a falcon or hawk (occasionally an eagle) sometimes rendered gold against a red backdrop and depicts the bird holding two orbs in its talons and adorned with an orb likewise above its head. The symbolism was meant to depict the bird guiding the Iranian peoples to conquest and to showcase aggression & strength coupled with dignity. The imperial family often kept falcons for the pastime of falconry.

Religion: The ancient Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism served as the official religion of the empire. It was adopted among the Persian elite & and had its unique beliefs but also helped introduce the concept of free-will among its believers, an idea to influence Judaism, Christianity & Islam in later centuries. Despite this official religion, there was a tolerance for local practices within the subject regions of the empire. The ancient Mesopotamian religion in Babylon & Assyria, Judaism, the Ancient Greek & Egyptian religions & Vedic Hinduism in India was likewise tolerated as well. The tolerance of the Achaemenids was considered a relative hallmark of their dynasty from the start. Famously, in the Old Testament of the Bible it was said that it was Cyrus the Great who freed the Jews from their Babylonian captivity and allowed them to return to their homeland of Judea in modern Israel.

Currency: Gold & silver or bimetallic use of coins became standard within the empire. The gold coins were later referred to as daric and silver as siglos. The main monetary production changes came during the rule of Darius I (522BC-486BC). Originally, they had followed the Lydian practice out of Anatolia of producing coins with gold, but the practice was simplified & refined under the Achaemenids.

Population: The estimates vary ranging from a low end of 17 million to 35 million people on the upper end circa 500BC. The official numbers are hard to determine with certainty but are generally accepted in the tens of millions with the aforementioned 17-35 million being the most reasonable range based on available sources.

Government: The government of the Achaemenid Empire was a hereditary monarchy ruled by a king or shah or later referred to as the ShahanShah or King of Kings, this is roughly equivalent to later use of the term Emperor. Achaemenid rulers due the unprecedented size of their empire held a host of titles which varied overtime but included: King of Kings, Great King, King of Persia, King of Babylon, Pharaoh of Egypt, King of the World, King of the Universe or King of Countries. Cyrus the Great founded the dynasty with his conquest first of the Median Empire and subsequently the Neo-Babylonians and Lydians. He established four different capitals from which to rule: Pasargadae as his first in Persia (southwest central Iran), Ecbatana taken from the Medians in western Iran's Zagros Mountains. The other two capitals being Susa in southwest Iran near and Babylon in modern Iraq which was taken from the Neo-Babylonians. Later Persepolis was made a ceremonial capital too. The ShahanShah or King of Kings was also coupled with the concept of divine rule or the divinity of kings, a concept that was to prove influential in other territories for centuries to come.

While ultimate authority resided with the King of Kings and their bureaucracy could be at times fairly centralized. There was an expansive regional bureaucracy that had a degree of autonomy under the satrapy system. The satraps were the regional governors in service to the King of Kings. The Median Empire had satraps before the Persians but used local kings they conquered as client kings. The Persians did not allow this because of the divine reverence for their ShahanShah. Cyrus the Great established governors as non-royal viceroys on his behalf, though in practice they could rule like kings in all but name for their respective regions. Their administration was over their respective region which varied overtime from 26 to 36 under Darius I. Satraps collected taxes, acted as head over local leaders and bureaucracy, served as supreme judge in their region to settle disputes and criminal cases. They also had to protect the road & postal system established by the King of Kings from bandits and rebels. A council of Persians were sent to assist the satrap with administration, but locals (non-Persian) could likewise be admitted these councils. To ensure loyalty to the ShahanShah, royal secretaries & emissaries were sent as well to support & report back the condition of each satrapy. The so called "eye of the king" made annual inspections of the satrapy to ensure its good condition met the King of Kings' expectations.

Generals in chief were originally made separate to the satrap to divide the civil and military spheres of government & were responsible for military recruitment but in time if central authority from the ShahanShah waned, these could be fused into one with the satrap and general in chiefs becoming hereditary positions.

To convey messages across the widespread road system built within the empire, including the impressive 2,700 km Royal Road which spanned from Susa in Iran to Sardis in Western Anatolia, the angarium (Greek word) were an institution of royal messengers mounted on horseback to ride to the reaches of the empire conveying postage. They were exclusively loyal to the King of Kings. It is said a message could be reached to anywhere within the empire within 15 days to the empire's vast system of relay stations, passing message from rider to rider along its main roads.

Military: The military of the Achaemenids consisted of mostly land based forces: infantry & cavalry but did also eventually include a navy.

Its most famous unit was the 10,000-man strong Immortals. The Immortals were used as elite heavy infantry were ornately dressed. They were said to be constantly as 10,000 men because for any man killed, he was immediately replaced. Armed with shields, scale armor and with a variety of weapons from short spears to swords, daggers, slings, bows & arrows.

The sparabara were the first line of infantry armed with shields and spears. These served as the backbone of the army. Forming shield walls to defend the Persian archers. They were said to ably handle most opponents and could stop enemy arrows though their shields were vulnerable to enemy spears.

There was also the takabara light infantry and though is little known of them it seems they served as garrison troops and skirmishers akin to the Greek peltast of the age.

The cavalry consisted of four distinct groups: chariot driven archers used to shoot down and break up enemy formations, ideally on flat grounds. There was also the traditional horse mounted cavalry and also camel mounted cavalry, both served the traditional cavalry functions and fielded a mix of armor and weapons. Finally, there was the use of war elephants which were brought in from India on the empire's eastern reaches. These provided archers and a massive way to physically & psychologically break opposing forces.

The navy was utilized upon the empire's reaching the Mediterranean and engaged in both battles at sea and for troop transport to areas where troops needing deploying overseas, namely in Greece.

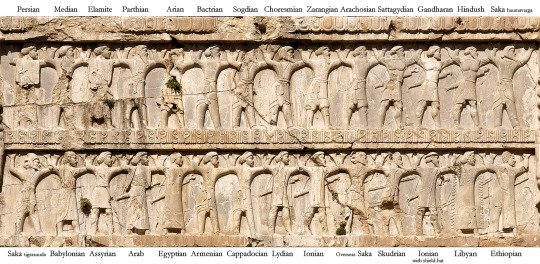

The ethnic composition of Achaemenid military was quite varied ranging from a Persian core with other Iranian peoples such as the Medians, Sogdian, Bactrians and Scythians joining at various times. Others including Anatolians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Anatolians, Indians, Arabs, Jews, Phoenicians, Thracians, Egyptians, Ethiopians, Libyans & Greeks among others.

Their opponents ranged from the various peoples they conquered starting with the Persian conquest of the Medians to the Neo-Babylonians, Lydians, Thracians, Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs & Indians and various others. A hallmark of the empire was to allow the local traditions of subjugated areas to persist so long as garrisons were maintained, taxes were collected, local forces provided levies to the military in times of war, and they did not rebel against the central authority.

Economy: Because of the efficient and extensive road system within the vast empire, trade flourished in a way not yet seen in the varied regions it encompassed. Tax districts were established with the satrapies and could be collected with relative efficiency. Commodities such as gold & jewels from India to the grains of the Nile River valley in Egypt & the dyes of the Phoenicians passed throughout the realm's reaches. Tariffs on trade & agricultural produce provided revenue for the state.

Lifespan: The empire was founded by Cyrus the Great circa 550BC with his eventual conquest of the Median & Lydian Empires. He started out as Cyrus II, King of Persia a client kingdom of the Median Empire. His reign starting in 559BC. Having overthrown and overtaken the Medians, he turned his attention Lydia and the rest of Anatolia (Asia Minor). He later attacked the Eastern Iranian peoples in Bactria, Sogdia and others. He also crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and attacked the Indus Valley getting tribute from various cities.

Cyrus then turned his attention to the west by dealing with the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Following his victory in 539BC at the Battle of Opis, the Persians conquered the Babylonia with relative quickness.

By the time of Cyrus's death his empire had the largest recorded in world history up to that point spanning from Anatolia to the Indus.

Cyrus was succeeded by his sons Cambyses II and Bardiya. Bardiya was replaced by his distant cousin Darius I also known as Darius the Great, whose lineage would constitute a number of the subsequent King of Kings.

Darius faced many rebellions which he put down in succession. His reign is marked by changes to the currency and the largest territorial expansion of the empire. An empire at its absolute zenith. He conquered large swaths of Egypt, the Indus Valley, European Scythia, Thrace & Greece. He also had exploration of the Indian Ocean from the Indus River to Suez Egypt undertaken.

The Greek kingdom of Macedon in the north reaches of the Hellenic world voluntarily became a vassal of Persia in order to avoid destruction. This would prove to be a fateful first contact with this polity that would in time unite the Greek-speaking world in the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. However, at the time of Darius I's the reign, there were no early indications of this course of events as Macedon was considered even by other Greek states a relative backwater.

Nevertheless, the Battle of Marathon in 490BC halted the conquest of mainland Greece for a decade and showed a check on Persia's power in ways not yet seen. It is also regarded as preserving Classical Greek civilization and is celebrated to this day as an important in the annals of Western civilization more broadly given Classical Greece & in particular Athens's influence on western culture and values.

Xerxes I, son of Darius I vowed to conquer Greece and lead a subsequent invasion in 480BC-479BC. Xerxes originally saw the submission of northern Greece including Macedon but was delayed by the Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae, most famously by Spartan King Leonidas and his small troop (the famed 300). Though the Persians won the battle it was regarded as a costly victory and one that inspired the Greeks to further resistance. Though Athens was sacked & burnt by the Persians, the subsequent victories on sea & land at Salamis & Plataea drove the Persians back from control over Greece. Though war would rage on until 449BC with the expulsion of the Persians from Europe by the Greeks.

However, the Greeks found themselves in a civil war between Athens & Sparta and Persia having resented the Athenian led coalition against their rule which had expelled them from Europe sought to indirectly weaken the Greeks by supporting Greek factions opposed to Athens through political & financial support.

Following this reversal of fortune abroad, the Achaemenid Empire not able to regain its foothold in Europe, turned inward and focused more on its cultural development. Zoroastrianism became the de-facto official religion of the empire. Additionally, architectural achievements and improvements in its many capitals were undertaken which displayed the empire's wealth. Artaxerxes II who reigned from 405BC-358BC had the longest reign of any Achaemenid ruler and it was characterized by relative peace and stability, though he contended with a number of rebellions including the Great Satraps Revolt of 366BC-360BC which took place in Anatolia and Armenia. Though he was successful in putting down the revolt. He also found himself at war with the Spartans and began to sponsor the Athenians and others against them, showcasing the ever dynamic and changing Greco-Persian relations of the time.

Partially for safety reasons, Persepolis was once again made the capital under Artaxerxes II. He helped expand the city and create many of its monuments.

Artaxerxes III feared the satraps could no longer be trusted in western Asia and ordered their armies disbanded. He faced a campaign against them which suffered some initial defeats before overcoming these rebellions, some leaders of which sought asylum in the Kingom of Macedon under its ruler Philip II (father of Alexander the Great).

Meanwhile, Egypt had effectively become independent from central Achaemenid rule and Artaxerxes III reinvaded in around 340BC-339BC. He faced stiff resistance at times but overcame the Egyptians and the last native Egyptian Pharaoh Nectanebo II was driven from power. From that time on ancient Egypt would be ruled by foreigners who held the title Pharaoh.

Artaxerxes III also faced rebellion from the Phoenicians and originally was ejected from the area of modern coastal Lebanon, Syria & Israel but came back with a large army subsequently reconquered the area including burning the Phoenician city of Sidon down which killed thousands.

Following Artaxerxes III's death his son succeeded him but a case of political intrigue & dynastic murder followed. Eventually Darius III a distant relation within the dynasty took the throne in 336BC hoping to give his reign an element of stability.

Meanwhile in Greece, due to the military reforms and innovations of Philip II, King of Macedon, the Greek speaking world was now unified under Macedon's hegemony. With Philip II holding the title of Hegemon of the Hellenic League, a relatively unified coalition of Greek kingdoms and city-states under Macedon premiership that formed to eventually invade Persia. However, Philip was murdered before his planned invasion of Asia Minor (the Achaemenid's westernmost territory) could commence. His son Alexander III (Alexander the Great) took his father's reforms and consolidated his hold over Greece before crossing over to Anatolia himself.

Darius III had just finished reconquering some rebelling vestiges of Egypt when Alexander army crossed over into Asia Minor circa 334BC. Over the course of 10 years Alexander's major project unfolded, the Macedonian conquest of the Persian Empire. He famously defeated Persians at Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela. The latter two battles against Darius III in person. He took the King of Kings family hostage but treated them well while Darius evacuated to the far eastern reaches of his empire to evade capture. He was subsequently killed by one of his relatives & satraps Bessus, whom Alexander eventually had killed. Bessus had declared himself King of Kings though this wasn't widely recognized and most historians regard Darius III, the last legitimate ShahanShah of Achaemenids.

Alexander had taken Babylon, Susa & Persepolis by 330BC and effectively himself was now ruler of the Persian Empire or at least its western half. In addition to being King of Macedon & Hegemon of the Hellenic League, he gained the titles King of Persia, Pharaoh of Egypt & Lord of Asia. Alexander would in time eventually subdue the eastern portions of the Achaemenid realm including parts of the Indus Valley before turning back to Persia and Babylon where he subsequently became ill and died in June 323BC at age 32. Alexander's intentions it appears were never to replace the Achaemenid government & cultural structure, in fact he planned to maintain and hybridize it with his native Greek culture. He was in fact an admirer of Cyrus the Great (even restoring his tomb after looting) & adopted many Persian customs and dress. He even allowed the Persians to practice their religion and had Persian and Greeks start to serve together in his army. Following his death and with no established successor meant the empire he established which essentially was the whole Achaemenid Empire's territory in addition to the Hellenic world fragmented into different areas run by his most trusted generals who established their own dynasties. The Asian territories from Anatolia to the Indus (including Iran and Mesopotamia) gave way to the Hellenic ruled Seleucid Empire while Egypt became the Hellenic ruled Ptolemaic Kingdom. The synthesis of Persian and Greek cultures continued in the Seleucid and Greco-Bactrian kingdoms of antiquity.

The Achaemenid Empire lasted for a little over two centuries (550BC-330BC) but it casted a long shadow over history. Its influence on Iran alone has persisted into the modern age with every subsequent Persian Empire claiming to be its rightful successor from the Parthian & Sasanian Empires of pre-Islamic Iran to the Safavids of the 16th-18th century and the usage of the title Shah until the last Shah's ejection from power in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Even the modern Islamic Republic of Iran uses Achaemenid imagery in some military regiments and plays up its importance in tourism and museums as a source of pride to Persian (Farsi) & indeed Iranian heritage. Likewise, its form of governance and the pushing of the concept of divine rights of kings would transplant from its Greek conquerors into the rest of Europe along with various other institutions such as its road & mail system, tax collection & flourishing trade. Its mix of centralized & decentralized governance. Its religious & cultural tolerance of local regions even after their conquest would likewise serve as a template for other empires throughout history too. The Achaemenid Empire served as a template for vast international & transcontinental empires that would follow in its wake & surpass its size & scope of influence. However, it is worth studying for in its time, it was unprecedented, and its innovations so admired by the likes of Alexander the Great and others echo into the modern era.

#military history#antiquity#iran#greece#ancient greece#classical greece#ancient ruins#ancient iran#ancient persia#achaemenid#persia#zoroastrianism#alexander the great#cyrus the great#xerxes#artwork#government#history#persian empire#ancient egypt

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

the "f*ck turkey club"

the iran oc is by @peonycats !! Sorry i forgot her ahoge 😭😭

#hetalia#aph uzbekistan#hws uzbekistan#aph hungary#hws hungary#aph romania#hws romania#hws greece#aph greece#heracles karpusi#erzsebet hedervary#aph iran#hws iran#turkuzbek#i see you guys liking turkuzbek so here#tokki draws

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross‐Cultural Encounters

1st INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE (ATHENS, 11‐13 NOVEMBER 2006)

Edited by Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi and Antigoni Zournatzi

National Hellenic Research Foundation

Cultural Center of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in

Athens

Hellenic National Commission for UNESCO

Athens, December 2008

Description

The extraordinary feats of conquest of Cyrus the Great and Alexander the Great have left a lasting imprint in the annals of world

history. Successive Persian and Greek rule over vast stretches of territory from the Indus to the eastern Mediterranean also created an

international environment in which people, commodities, technological innovations, as well as intellectual, political, and artistic ideas could circulate across the ancient world unhindered by ethno-cultural and territorial barriers, bringing about cross-fertilization between East and West. These broad patterns of cultural phenomena are illustrated in twenty-four contributions to the first international conference on ancient Greek-Iranian interactions, which was organized as a joint Greek and Iranian initiative.

Contents

Preface (Ekaterini Tzitzikosta)

Conference addresses (Dimitrios A. Kyriakidis, Seyed Taha Hashemi Toghraljerdi, Mir Jalaleddin Kazzazi, Vassos Karageorghis,

Miltiades Hatzopoulos, Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi, Massoud Azarnoush, David Stronach)

Introduction (Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi and Antigoni Zournatzi)

Europe and Asia: Aeschylus’ Persians and Homer’s Iliad (Stephen Tracy)

The death of Masistios and the mourning for his loss (Hdt. 9.20-25.1) (Angeliki Petropoulou)

Magi in Athens in the fifth century BC? (Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou)

Hājīābād and the dialogue of civilizations (Massoud Azarnoush)

Zoroastrianism and Christianity in the Sasanian empire (fourth century AD) (Sara Alinia)

Greco-Persian literary interactions in classical Persian literature (Evangelos Venetis)

Pseudo-Aristotelian politics and theology in universal Islam (Garth Fowden)

The system Artaphernes-Mardonius as an example of imperial nostalgia (Michael N. Weiskopf)

Greeks and Iranians in the Cimmerian Bosporus in the second/first century BC: new epigraphic data from Tanais (Askold I.

Ivantchik)

The Seleucids and their Achaemenid predecessors: a Persian inheritance? (Christopher Tuplin)

Managing an empire — teacher and pupil (G. G. Aperghis)

The building program of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and the date of the fall of Sardis (David Stronach)

Persia and Greece: the role of cultural interactions in the architecture of Persepolis— Pasargadae (Mohammad Hassan Talebian)

Reading Persepolis in Greek— Part Two: marriage metaphors and unmanly virtues (Margaret C. Root)

The marble of the Penelope from Persepolis and its historical implications (Olga Palagia)

Cultural interconnections in the Achaemenid West: a few reflections on the testimony of the Cypriot archaeological record

(Antigoni Zournatzi)

Greek, Anatolian, and Persian iconography in Asia Minor: material sources, method, and perspectives (Yannick Lintz)

Imaging a tomb chamber: the iconographic program of the Tatarlı wall paintings (Lâtife Summerer). Appendix: Tatarli Project:

reconstructing a wooden tomb chamber (Alexander von Kienlin)

The Achaemenid lion-griffin on a Macedonian tomb painting and on a Sicyonian mosaic (Stavros A. Paspalas)

Psychotropic plants on Achaemenid style vessels (Despina Ignatiadou)

Achaemenid toreutics in the Greek periphery (Athanasios Sideris)

Achaemenid influences on Rhodian minor arts and crafts (Pavlos Triantafyllidis)

Historical Iranian and Greek relations in retrospect (Mehdi Rahbar)

Persia and Greece: a forgotten history of cultural relations (Shahrokh Razmjou)

The editors

Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi is General Director of Cultural Offices of the Islamic Republic of Iran for Europe and the Americas.

Antigoni Zournatzi is Senior Researcher in the Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity, National Hellenic Research

Foundation. Her work focuses on the relations between Achaemenid Persia and the West.

The whole volume can be found as pdf on:

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

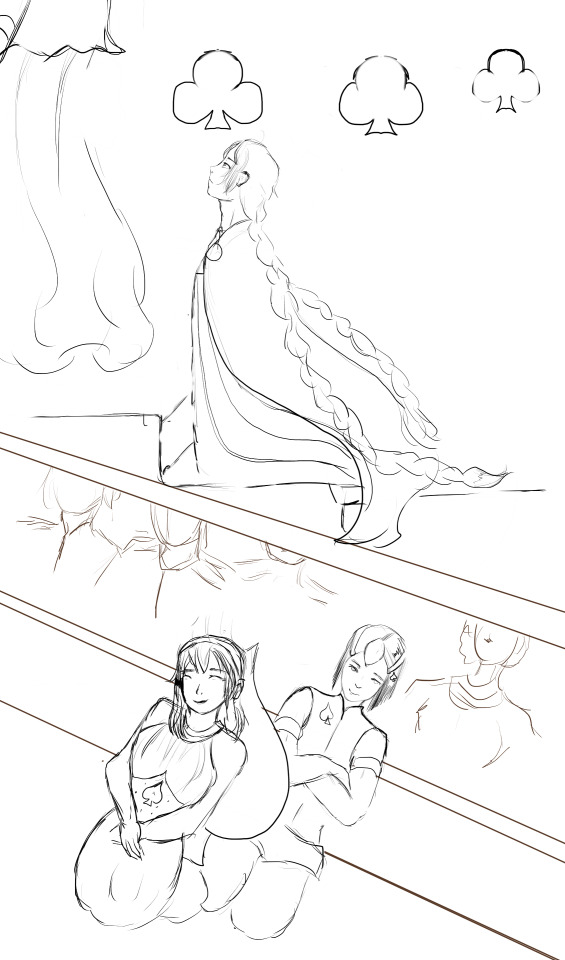

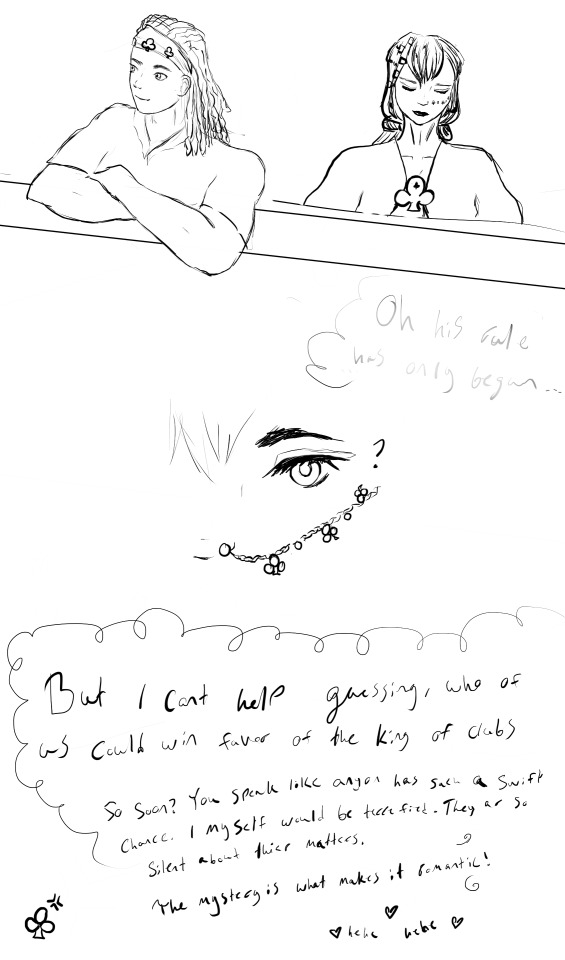

It's on me for having hubris, I would have loved to color these but mma be honest, still lining whats to come.

Day one of my piece for Cardverse!: Day 1: Royalty - arranged marriage | coronation | tradition

A joyous day as all the courts gather to attend the coronation of the new king of clubs (Kugelmugel) The future is full of wonder and wishes. Clubs, a kingdom of it's own, mingles as little as possible with the other kingdoms, for some this is there very first time being on the very soil. Many can't help but gossip what a new king of clubs could mean for it's own kingdom and everyone else. Perhaps even, a kingdom may manage to utilize the new rule and work to lift the veil by offering one of their own.

#cardverse week 2023#hetalia#cardverse#club hws kugelmugel#club hws cuba#club hws 2p nyo egypt#club hws nyo egypt#spade hws ancient egypt#spade hws egypt#diamond shiv#diamond hws china#diamond hws portugal#diamond hws iran#hearts hws england#hearts hws greece#hearts hws egypt#hearts hws romania#hearts hws cyprus#hearts hws ancient persia

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI Technology reimagines countries as beautiful women. By @CryptoTea on Twitter. The AI technology used both features of attractive women and cultural elements of the respective countries. More countries there

USA

The United Kingdom

Germany

Nigeria

Iran

Japan

Norway

Mexico

Greece

India

Italy

Turkey

Ukraine

China

Portugal

Saudi Arabia

Australia

Pakistan

Ethiopia

France

Russia

Venezuela

#art#a.i. generated#a.i. art#a.i. technology#digital art#countries#USA#uk#India#Australia#Greece#Turkey#Iran#Venezuela#Italy#France#Portugal#Mexico#Norway#Germany#Saudi Arabia#Nigeria#Ethiopia#China#Japan#Ukraine#Russia#Pakistan

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, I think the situation around the perception of iranian history and greek history in fandom is quite similar.

Let's be honest, for most people there is only Ancient Greece (by which they mean the history of the classical greek city-states + hellenistic period + roman period, we are not particularly touching on the dark ages and bronze age Mycenaean Greece, not to mention earlier times), which they - following the manga/anime canon - separate from modern Greece. And there is modern Greece, which, in general, began its independent existence in the first half of the nineteenth century, when a small piece of territory in the southern Balkans gained independence and was called “Hellas”. At best, they have ottoman rule as a kind of “preparatory period” when the canonical Iraklis grew up, did not understand anything and did not really decide anything. And at the same time, modern Greece is the son of Ancient Greece, who loves to be nostalgic about his cool mother, who did something great there more than two thousand years ago. Cool, yeah.

Likewise, for most people there is "ancient Persia" (before the conquest of the Islamic Caliphate in the 7th and 8th centuries AD) and "modern Iran", which they count from the Islamization of the Iranian plateau. In the manga canon, we have a character called "Persia", who people unthinkingly identify with the Achaemenid state, the Parthian Arsacid state, and the Sassanid state. In fanon, he (“Persia”) actively interacts (at war) with Rome, interacts with China and India in much rarer cases, and the mangaka also mentioned that he has descendants, one of which is “modern” Iran, yes. And, of course, there is an incredible amount of time devoted to the Achaemenid period (but not the greco-persian Wars, which shocked me when researching the fandom). Cool, yeah.

But you know what's surprising? None of this makes any sense.

If we take Greece... no, we take greek culture, we will understand that it has continuously developed, without gaps, from the time of the classical polis until the present moment, BUT, if you really want to find a watershed, then this is late antiquity. Why? Because in late antiquity, the pagan hellenes, living in their separate city-states as citizens, became christian rhomeans, subjects of the vast Eastern Roman Empire (which in fact is still perceived as a Republic). The roman "imperial" identity replaced the greek polis identity - although the greek language still dominated in the East, especially after the Avar conquest of the Balkans, when the Empire lost the latin-speaking provinces. The perception of “hellenic” identity was very complex, it experienced a revival, especially in the 13th century, when the roman/latin identity began to be associated with the germans/italians/franks, enemies of the Eastern Empire, but this is if we are talking about intellectuals - the people considered themselves rhomeans. And guess what? The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 did not change anything! There was no break or fracture! The Church of Constantinople continued to be the guardian of this identity even in the absence of christian imperial power! And the people who started the Greek Revolution in the 19th century did not strive to create a small national state, no, in their eyes ALL of Anatolia and the Balkans were the historical lands of the Eastern Roman Empire, which they considered their country. The fascination with ancient pagan Greece is something that was brought from the West, which despised “Byzantium”.

And if you look at Iran, the real boundary between "ancient" and "modern" history is the conquest of Alexander the Great. Because - this will amaze many - but until the second half of the 19th century in Iran itself they knew nothing about the ancient history of the country! The first historical event preserved in chronicles and art, say, the "Shahnameh" of Ferdowsi, is the conquest of Alexander, which has nothing to do with the real one (I will only say that Alexander is considered a descendant of the iranian royal dynasty there). In Iran, they knew almost nothing about the greco-persian wars, about the Seleucids, about the parthian Arsacids and the roman-parthian wars! The real history in Iranian perception began only with the Sassanids, who were at enmity with “Rum” - but, first of all, not with Western, decrepit Rome, but with Eastern Rome! It was “Byzantium” that was “Rome” for the Iranians and for the entire Middle East until the 19th century, while the Western “latins” were the “franks”. Moreover, I want to note that the complete forgetting of the history of the country before Alexander in Iran began even under the Sassanids - largely because ancient persian was a cuneiform language, and cuneiform was forgotten (as for the iranian epic, its oldest part is eastern iranian in origin, western iranian, persian, it becomes only from the time of Ardashir the First). But the arab conquest and adoption of islam did not have such consequences! And when the revival of iranian culture and the new persian language began in the 9th-10th centuries A.D., it was a revival, albeit rethought, of Sassanian identity.

In short, while it makes sense to separate Ancient Greece from "Byzantium", it makes no sense to separate "Byzantium" from modern Greece. And the history of modern Iran begins with the Sassanids, not Islamization.

#hetalia meta#hetalia#aph#hws#aph greece#hws greece#aph byzantine empire#hws byzantine empire#aph persia#hws persia#aph iran#hws iran

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hetalia polls#hetalia#aph iran#aph saudi arabia#aph mongolia#aph china#aph egypt#aph greece#aph turkey#aph england#aph denmark#aph Ethiopia#aph india

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Al-Rhazi and Ibn Sina kept alive and advanced much medical knowledge that had largely vanished from Europe – knowledge that had originated in Ancient Greece and Rome, and then spread through Constantinople and Gundeshapur to Baghdad and Bukhara, where it was combined with learnings from India and China, and was eventually translated back into European languages to form a basis for the flowering of the Renaissance. This reawakening of Classical thought inaugurated the age of the university, when medical schools were established throughout Europe, the Middle East, and beyond.

— Kill or Cure: An Illustrated History of Medicine (Steve Parker)

#book quotes#steve parker#kill or cure: an illustrated history of medicine#history#classics#medicine#medical history#academia#education#islamic golden age#enlightenment#renaissance#persia#iran#ancient greece#ancient rome#abu bakr al-razi#ibn sina#avicenna

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi babes.

The LORD showed me the flag of Greece as well

🇬🇷

It was waving proudly in the air.

In all honesty I am not sure of the meaning of this however, it may have something to do with standing with Israel 🇮🇱

It could be something else as well. Remember what God showed us about Greece a year ago wayyyyy before Hamas’ brutal murderous attack on innocent Israeli’s.

I made a whole video but I guess I’ll share some of it here…

Iran is continuing with its efforts to secure a nuclear weapon. God has been trying to send the message discreetly but it seems that isn’t working. Look and you’ll see.

I also heard the word “deterrent”.

——————-

Thank you to all the allies that stood against this unprecedented assault on Israel and its citizens but also the attack on the LORD’s Holyland. 300+ missiles. Imagine they were able to land.

I have more to share.

Let’s us keep praying for peace and the end to Iran’s oppressive regime. This is so much bigger than an Israeli-Hamas problem. Just wow.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine hetalia characters having a parent-like relationship with their first leader

Like a very young france listening at night near a fire to clovis's stories about his grand-father mérovée.

or greece being physically 8 year old and arguing with constantine I about the gestion of the donatist crisis

A small Iran being a little shit acting all smug in front of lydia and then hiding behind cyrus the great before he gets caught

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macedonia and Achaemenid Persia Gijinka

#ancient history#ancient macedonia#ancient greece#achaemenid empire#achaemenid#ancient iran#gijinka#digital drawing

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Releases in August for the YA World Challenge

Here is a repost of my August releases list because Tumblr made my other blog invisible. It is a selection of global-inspired YA books that came out this month!

(all the links below go to supporting independent bookstores [not Amazon!])

🇨🇦 Canada

Blood Like Fate - Liselle Sambury

🇨🇳 China

A Venom Dark and Sweet - Judy I. Lin

🇨🇳 🇺🇸 Chinese-American

The Lies We Tell - Katie Zhao

🇫🇷 France

Cake Eater - Allyson Dahlin

🇬🇷 Greece

Daughter of Darkness - Katharine Corr & Elizabeth Corr

🇮🇳 India

Meet Me in Mumbai - Sabina Khan

🇮🇷 🇺🇸 Iranian-American

Azar on Fire - Olivia Abtahi

🇯🇵 Japan

The Dragon’s Promise - Elizabeth Lim

Alliana, Girl of Dragons, Julie Abe

🇳🇬 Nigeria

How You Grow Wings - Rimma Onoseta

🇬🇧 Scotland

Beguiled - Cyla Panin

🌍 West Africa

Master of Souls - Rena Barron

🇬🇧 Wales

The Drowned Woods - Emily Lloyd-Jones

#book list#new releases#ya world challenge#ya books#bookblr#booklr#book tumblr#canada#china#france#greece#india#iran#japan#nigeria#scotland#wales#africa#asia#north america#middle east#europe

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

"BMCR 2009.10.48

Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross-Cultural Encounters. 1st International Conference (Athens, 11-13 November 2006)

Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi, Antigoni Zournatzi, Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross-Cultural Encounters. 1st International Conference (Athens, 11-13 November 2006). Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation; Hellenic National Commission for UNESCO; Cultural Center of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2008. xxix, 377. ISBN 9789609309554. €60.00 (pb).

Review by

Margaret C. Miller, University of Sydney. [email protected]

[Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review.]

The volume commemorates a landmark occasion, when the national research centres of Iran and Greece collaborated in a multi-national interdisciplinary conference on the history of exchange between Iran and Greece. Its nearly 400 pages reflect a strong sense of its symbolic importance. Papers span the Achaemenid through the Mediaeval periods and address the theme of exchange from the perspective of many disciplines — history, art, religion, philosophy, literature, archaeology. The book thus brings together material that can be obscure outside the circle of specialists, and in a manner that is generally accessible; the wide range of topics and periods included is a strength. Excellent illustrations often in colour enhance the archaeological contributions, as does inclusion of hitherto unpublished material.

The volume commences with a brief section on what might be called Greek textual evidence (Tracy, Petropoulou, Tsanstanoglou), followed by papers on interaction in Sasanian through mediaeval Persia (Azarnoush, Alinia, Venetis, Fowden), four papers discussing Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian history (Weiskopf, Ivantchik, Tuplin, Aperghis), aspects of the archaeology of Persepolis and Pasargadae (Stronach, Talebian, Root, Palagia), and ends with essays on the receptivity to Achaemenid culture in the material culture of the western empire and fringes: Cyprus, Turkey, Greece (Zournatzi, Lintz, Summerer, Paspalas, Ignatiadou, Sideris, Triantafyllidis), followed by a paper on traces of Greek material culture in the archaeology of (Seleucid) Iran (Rahbar). The wealth of vehicles, contexts and levels of exchange attested through the ages is both eye-opening and exciting. While there is unfortunately little attempt at globalizing synthesis or theoretical modelling, the analytical methods and collections of data in the individual contributions will aid future work in the area.

Stephen Tracy starts the volume with a synchronic analysis of the ways in which first Aeschylus, then Homer, play upon the prejudices of their audience against ” barbaroi” and then show the human quality of the enemy. In Persai, the Athenians are anonymous in contrast with the delineated personalities of the Persian royal family; in the Iliad, Achilles is “not very likeable” but learns humanity from the sorrow of Priam. Both poets focus on common humanity that transcends short-term hostilities.

Angeliki Petropoulou offers a detailed analysis of Herodotus’ account of the death of Masistios and subsequent mourning (Hdt. 9.20-25.1). Herodotus played up the heroic quality of Masistios’ death, stressing his beauty and height, qualities appreciated by both Greeks and Persians. The fact that Masistios seems to have gained the position of cavalry commander in the year before his death, coupled with the likelihood that his Nisaian horse with its golden bridle was a royal gift, suggests he had been promoted and rewarded for bravery.

Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou discusses the Derveni papyrus’ mention of magoi (column VI.1-14). Though the papyrus dates 340-320, the text was composed late fifth century BC, making the apparently Iranian content especially important. Both the ritual described and the explanation for it cohere with elements known from later Persian sources as features of early Iranian religious thought. While the precise vehicles of transmission of such knowledge to the papyrus are unknowable, the papyrus is the first certain documentation of the borrowing of Iranian ideas in Greek (philosophical) thought.

On the Iranian side exchange of religious ideas is documented by Massoud Azarnoush in the iconography of a fourth-century AD Sasanian manor-house he excavated at Hajiabad 1979.1 Moulded stucco in the form of divine figures included dressed and naked females identified with Anahita. The very broad shoulders of the Hellenistically dressed Anahita fit an Iranian aesthetic; the closest parallel for the slender naked females is found not in the cognate Ishtar type but in the Aphrodite Pudica type. Reliefs of naked boys, of uncertain relationship with Anahita, have attributes of fertility cult in the (Dionysian?) bunches of grapes they hold and in the ?ivy elements of their headdress.

Sara Alinia offers a brief but fascinating account of the development of state-sponsored religion hand-in-hand with state-sponsored persecution of religious elements that were deemed to be affiliated with another state: the Christian Late Roman Empire and the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire. She documents the rise of religion as a tool of inter-state diplomacy and vehicle for inter-state rivalry; religion was but one facet of the political antagonism between the two.

Evangelos Venetis studies the cross-fertilization between Hellenistic and Byzantine Greek romance and Iranian pre-Islamic and Islamic romantic narrative. Persian elements are found in Hellenistic romance; Hellenistic themes contribute to Persian epics. The fragmentary nature of texts ranging 2nd -11th/14th c. AD and the lack of intermediary texts are serious impediments which may yet be overcome. The Alexander Romance, known in Iran from a Sasanian translation, contributed to the form and detail of the Shahname, as well as to other Persian epics.

Garth Fowden outlines the complex history of the creation, translation, wide circulation and impact of the pseudo-Aristotelian texts on religious thought. Aristotle’s works were translated into Syriac in the 6th c. and in the mid 8th c. into Arabic. Arab philosophers, attracted to the idea of Aristotle as counsellor of kings, updated him. Owing to his remoteness in time, “Aristotle” offended neither Muslim nor Christian. The Letters of Alexander, Secret of Secrets and al-Kindi’s sequel of Metaphysics, the Theology of Aristotle, contributed significantly to the philosophical underpinnings of both Muslim and Christian theology; the last remains an important text in teaching at Qom.

Michael N. Weiskopf argues that Herodotos’ account of the Persian treatment of Ionia after the Ionian revolt constitutes “imperial nostalgia” — the popular memory of how good things were under a past regime, in the context of a new regime. Herodotos 6.42-43, stressing the administrative efficiency and fairness of Artaphernes’ arrangements, allows a reading of Mardonios’ alleged imposition of democratic constitutions (so dissonant with the subsequent reported governing of Ionian states) as imperial nostalgia, to be contrasted with the inconsistent and unfair treatment of the Ionians by the Athenians of Herodotos’ own day.

Askold I. Ivantchik publishes two Greek inscriptions from Hellenistic Tanais in the Bosporos (and reedits a third). Evidently private thiasos inscriptions, they confirm that the city was already in 2nd or 1st century BC officially divided into two social (presumably ethnic) groups: the Hellenes and the Tanaitai, presumably Sarmatians, on whose land the city was founded in the late 3rd century BC. A thiasos for the river god Tanais includes members with both Greek and Iranian names, showing that private religious thiasoi were an important vehicle for breaking down social barriers between the two populations of the city.

Two papers offer contrasting interpretations of the evidence for Seleucid retention of Achaemenid institutions. That there were parallels between structures of the different periods is uncontested; the question is whether the parallels signify a deliberate programme of Seleucid self-presentation as the “heirs of the Achaemenids.” Christopher R. Tuplin argues that acquisition of the empire involved adoption of the Achaemenid mantle in some contexts and maintenance of those structures that worked, but that the balance of evidence suggests no conscious policy of continuation, and considerable de facto alteration of attitude and form. He suggests that the evidence of continuity of financial (taxation) structures — a major part of Aperghis’ argument — is ambiguous, at best. The treatment and divisions of territory, most notably the “shift of centre of gravity” from Persis to Babylonia, argue more for disruption than continuity.

G. G. Aperghis gives the case for a deliberate Seleucid policy of continuation of many Achaemenid administrative practices. He points to the retention of the satrapy as basis of administrative organization; use of land-grants (albeit to cities rather than individuals); continuing royal support of temples; maintenance of the Royal Road system (n.b. two Greek milestones, one illustrated in this volume by Rahbar); the retention of two separate offices relating to financial oversight. He suggests that the double sealing of transactions in the Persepolis Fortification Tablets metamorphosed into the double monogram on Seleucid coinage. Further field work in Iran, like that outlined by Rahbar (see below), will settle such contested matters as whether the many foundations of Alexander had any local impact. At present, Tuplin offers the more persuasive case.

David Stronach, excavator of Pasargadae, gives his considered opinion on the complex nexus of issues relating to the date of Cyrus’ constructions at Pasargadae. Touching upon the East Greek and Lydian contribution to early Achaemenid monumental architecture in stone and orthogonal design principles, Cyrus’ conquest chronology and the Nabonidus Chronicle, Darius’ creation of Old Persian cuneiform, the elements of the Tomb of Cyrus, and new evidence confirming the garden design, he argues that the chronology of the constructions at Pasargadae indirectly confirms the date of the conquest of Lydia around 545.

Mohammad Hassan Talebian offers a diachronic analysis of Persepolis and Pasargadae, starting with a survey of the Iranian and Lydian elements in their construction. Modern interventions include the ill-informed and damaging activities of Herzfeld and Schmidt at Persepolis in the 1930s, the stripping away of the mediaeval Islamic development of the Tomb of Cyrus, and the damage to the ancient city of Persepolis in preparation for the 2500-anniversary celebrations in 1971. Recent surveys in the region compensate to some degree. Talebian urges the importance of attention to all periods of the past rather than a privileged few.

Margaret Cool Root continues her thought-experiment in exploring how a fifth-century Athenian male might have viewed Persepolis.2 Sculptural traits such as the emphasis on the clothed body and nature of interaction between individuals would have seemed to the hypothetical Athenian to embody a profoundly effeminate culture. Yet Root’s study of the Persepolis Fortification Tablet sealings, their flashes of humour and playfulness in their utilisation on the tablets, reveals a world in which oral communication — idle chit-chat — perhaps bridged the cultural divide. She concludes that a visiting Greek might well have learned how to read the imagery like an Iranian.

Olga Palagia argues that the most famous Greek artefact found at Persepolis, the marble statue of “Penelope”, was not booty but a diplomatic gift from the people of Thasos: its Thasian marble provides a workshop provenance. The “Polygnotan” character, seen also in the Thasian marble “Boston Throne,” possibly from the same workshop, suits the prestige of the gift: Thasos’ great artist, the painter Polygnotos, is also attested as a bronze sculptor. A putative second Penelope in Thasos, taken to Rome in the imperial period with the “Boston Throne,” would have served as model for the Roman sculptural versions.

Antigoni Zournatzi offers the first of a series of regional studies documenting receptivity to Persian culture in the western empire and beyond, with a look at Cyprus. Earlier scholarship focused on siege mound and palace design; receptivity can be tracked in glyptic, toreutic, and sculpture. Western “Achaemenidizing” seals may be Cypriote; Persianizing statuettes may reflect local adoption of Persian dress (or Persian participation in local ritual). The treatment of beard curls on one late 6th century head may reflect Persian sculptural practice. Zournatzi suggests that Cypro-Persian bowls and jewellery were produced not for local consumption but to satisfy tribute requirements.

Yannick Lintz announces a project to compile a comprehensive corpus of Achaemenid objects in western Turkey, an essential step in any attempt to understand the period in the region.3 Particular challenges lie in matters of definition, both of “Achaemenid” and “west Anatolian” traits. The state of completion of the database is not clear; one is aware of a volume of excavated material in museums whose processing and publication was interrupted and can only wish her well in what promises to be a massive undertaking.

Lâtife Summerer continues her publication of the Persian-period Phrygian painted wooden tomb at Tatarli in western Turkey with discussion of the different cultural elements of its iconographic programme.4 The friezes of the north wall especially present Anatolian traditions; the east wall friezes of funerary procession and battle (between Persians and nomads) offer a mix of Persian and Anatolian. New Hittite evidence clinches as Anatolian the identification of the cart with curved top familiar in Anatolo-Persian art; it carries an effigy of the deceased. Alexander von Kienlin’s appendix expands the cultural mix presented by the tomb with his demonstration that its Lydian-style dromos was an original feature.

Stavros Paspalas raises questions about the vehicles and route of cultural exchange between the Persian Empire and Macedon through analysis of Achaemenid-looking lion-griffins on the façade of the later fourth century tomb at Aghios Athanasios. He identifies a pattern of specifically Macedonian patronage of Achaemenid imagery also in southern Greece in the fourth century in such items as the pebble mosaic from Sikyon and the Kamini stele from Athens. Enough survives to suggest independent local Macedonian receptivity to Persian ideas rather than a secondary derivation through southern Greece.

Despina Ignatiadou summarises succinctly the growing corpus of Achaemenidizing glass and metalware vessels in 6th-4th century BC Macedon. Three foreign plants lie behind the forms of lobe and petal-decoration on phialai, bowls, jugs, and beakers: the central Anatolian opium poppy, the Egyptian lotus (white and blue types) and the Iranian/Anatolian (bitter) almond. The common denominator is their medicinal and psychotropic qualities; Ignatiadou suggests that their appearance on vessels has semiotic value and that such drugs were used in religious and ritual contexts along with the vessels that carry their signatures, perhaps especially in the worship of the Great Mother.

Athanasios Sideris outlines the range of issues related to understanding the role of Achaemenid toreutic in documenting ancient cultural exchange: production ranges between court, regional, and extra-imperial workshops, not readily distinguishable. The inclusion of little-known material from Delphi and Dodona enriches his discussion of shape types. He works toward identification of local workshops, both within and without the empire, based especially on apparent local preferences in surface treatment. The geographical range of production is one area that will benefit from further international research collaboration.5

Pavlos Triantafyllidis focuses on the wealth of material from Rhodes, both sanctuary deposits and well-dated burials, that attests a history of imports from Iran and the Caucasus even before the Achaemenid period. Achaemenid-style glass vessels start in the late 6th century with an alabastron and petalled bowl, paralleled in the western empire, and carry on through the fourth century. An excavated fourth-century glass workshop created a series of “Rhodio-Achaemenid” products that dominated Rhodian glassware through the early third century. This microcosmic case study brilliantly exemplifies a much broader phenomenon.

Mehdi Rahbar outlines and illustrates archaeological material, some not previously published, that will be fundamental in future discussions of Seleucid Iran. The as of yet limited corpus includes: modulation of Greek forms perhaps to suit a local taste (Ionic capital from the temple of Laodicea, Nahavand, known from an 1843 inscription of Antiochus III; fragmentary marble sculpture of Marsyas?), amalgam of Iranian and Greek (milestone in Greek with Persepolitan profile), Greek import (Rhodian stamped amphora handle ΝΙΚΑΓΙΔΟΣ from Bisotun);6 and Iranian adoption of Greek decorative elements (vine leaves, grapes, and acanthus patterns, for which compare Azarnoush’s stucco).

The volume concludes with a brief overview of ancient Iranian-Greek relations and their modern interpretation by Shahrokh Razmjou.

The inclusion of the texts of the introductory and concluding addresses made on the occasion of the conference in particular allow the reader to comprehend its aims: hopes of exchange in the modern world through assessing exchange in the past. A number of the papers make it very clear that collaboration between specialists of “East” and “West” in both textual and archaeological research could yield great gains for all periods of history and modes of analysis. The conference and its publication, therefore, succeed at a variety of levels.

Editing such a volume must have been a real challenge and it is to the credit of authors and editors that throughout the whole volume, I found only a handful of minor infelicities and typographical errors, none of which obscure meaning.7

Contents: Stephen Tracy, “Europe and Asia: Aeschylus’ Persians and Homer’s Iliad” (1-8)

Angeliki Petropoulou, “The Death of Masistios and the Mourning for his Loss” (9-30)

Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou, “Magi in Athens in the Fifth Century BC?” (31-39)

Massoud Azarnoush, “Hajiabad and the Dialogue of Civilizations” (41-52)

Sara Alinia, “Zoroastrianism and Christianity in the Sasanian Empire (Fourth Century AD)” (53-58)

Evangelos Venetis, “Greco-Persian Literary Interactions in Classical Persian Literature” (59-63)

Garth Fowden, “Pseudo-Aristotelian Politics and Theology in Universal Islam” (65-81)

Michael N. Weiskopf, “The System Artaphernes-Mardonius as an Example of Imperial Nostalgia” (83-91)

Askold I. Ivantchik, “Greeks and Iranians in the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Second/First Century BC: New Epigraphic Data from Tanais” (93-107)

Christopher Tuplin, “The Seleucids and Their Achaemenid Predecessors: A Persian Inheritance?” (109-136)

G. G. Aperghis, “Managing an Empire—Teacher and Pupil” (137-147)

David Stronach, “The Building Program of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and the Date of the Fall of Sardis” (149-173)

Mohammad Hassan Talebian, “Persia and Greece: The Role of Cultural Interactions in the Architecture of Persepolis-Pasargadae” (175-193)

Margaret Cool Root, “Reading Persepolis in Greek—Part Two: Marriage Metaphors and Unmanly Virtues” (195-221)

Olga Palagia, “The Marble of the Penelope from Persepolis and its Historical Implications” (223-237)

Antigoni Zournatzi, “Cultural Interconnections in the Achaemenid West: A Few Reflections on the Testimony of the Cypriot Archaeological Record” (239-255)

Yannick Lintz, “Greek, Anatolian, and Persian Iconography in Asia Minor : Material Sources, Method, and Perspectives” (257-263)

Latife Summerer, “Imaging a Tomb Chamber : The Iconographic Program of the Tatarli Wall Paintings” (265-299)

Stavros Paspalas, “The Achaemenid Lion-Griffin on a Macedonian Tomb Painting and on a Sicyonian Mosaic” (301-325)

Despina Ignatiadou, “Psychotropic Plants on Achaemenid Style Vessels” (327-337)

Athanasios Sideris, “Achaemenid Toreutics in the Greek Periphery” (339-353)

Pavlos Triantafyllidis, “Achaemenid Influences on Rhodian Minor Arts and Crafts” (355-366)

Mehdi Rahbar, “Historical Iranian and Greek Relations in Retrospect” (367-372)

Shahrokh Razmjou, “Persia and Greece: A Forgotten History of Cultural Relations” (373-374)

Notes

1. The site is fully published in: M. Azarnoush, The Sasanian manor house at Hajiabad, Iran (Florence 1994).

2. The first appears as “Reading Persepolis in Greek: gifts of the Yauna,” in C. Tuplin, ed., Persian Responses: Political and Cultural Interaction with(in) the Achaemenid Empire (Swansea 2007) 163-203.

3. Deniz Kaptan is similarly compiling a corpus of Achaemenid seals and sealings in Turkish museums.

4. Other studies: “From Tatari to Munich. The recovery of a painted wooden tomb chamber in Phrygia”, in I. Delemen, ed., The Achaemenid Impact on Local Populations and Cultures (Istanbul 2007), 129-56; “Picturing Persian Victory: The Painted Battle Scene on the Munich Wood”, in A. Ivantchik and Vakhtang Licheli, edd., Achaemenid Culture and Local Traditions in Anatolia, Southern Caucasus and Iran: New Discoveries (Leiden/Boston 2007: Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 13), 3-30.

5. Considerable progress is being made, e.g., in Georgia: V. Licheli, “Oriental Innovations in Samtskhe (Southern Georgia) in the 1st Millennium BC,” and M. Yu. Treister, “The Toreutics of Colchis in the 5th-4th Centuries B.C. Local Traditions, Outside Influences, Innovations,” both Ivantchik / Licheli, edd., Achaemenid Culture and Local Traditions in Anatolia (previous note), 55-66 and 67-107.

6. For early 2nd c. date of this fabricant, see Christoph Börker and J. Burow, Die hellenistischen Amphorenstempel aus Pergamon: Der Pergamon-Komplex; Die Übrigen Stempel aus Pergamon (Berlin 1998), cat. no. 274-286; one example has a context of ca. 200 BC.

7. Except possibly the misprint on p. 357, line 8 up, where “second century” should presumably be “second quarter” (of the fourth century)."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Generated a bunch of AI people from every single country and made a video out of it. Of course, the clothing may not be completely accurate to every culture and all that. I'm no expert on that stuff. But see what you think!

#midjourney#international#every country#cyprus#chad#iran#greece#macedonia#georgia#ireland#finland#guinea bissau#equatorial guinea#papua new guinea#guinea#mongolia#norway#germany#sweden#canada#united states#italy#france#bhutan#ukraine#uganda#china#brazil#south korea#south africa

7 notes

·

View notes