#language acqusition

Note

how good is your japanese? did it take a while to learn? i tried to learn it for ages and the alphabet stumped me before i could get very far

My Japanese is fine, but keep in mind I've lived here for nearly 8 years. I was conversational by the end of my first year, only because... well... I didn't really have a choice?

I saw Japanese everywhere, and heard it every day. It's hard to ignore input like that. Your brain picks it up whether you like it or not. However, if I didn't have that sort of exposure, I'm sure my learning would be slowed immensely.

It's very difficult to learn a language without some sort of daily reinforcement. Also, learning by being immersed in a language and learning it just from books/apps makes a huge difference.

Along those same lines, there's also the reality of motivating yourself to remember shit that, realistically, you'll rarely use if you don't have a reason to see/hear Japanese constantly.

Sometimes, people are very good at creating their own motivation, and learning from resources and textbooks. But if you're not a super-motivator, it's hard to convince your brain to remember something you won't use daily. That's not really a failure on your part, that's just your brain being efficient.

#people sometimes say#oh youre good at languages#actually no im not#i just tend to put myself into situations where its learn or perish#thats like learning to be a good runner by living with lions#language#linguistics#japanese#bilingual#language acqusition

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's interesting that people believe children are better at acquiring new languages than adults. I think that's largely an artifact of children having free time to learn new things full-time & to some small degree not having the sort of internal filter adults have, where they're convinced both that they can't (and thus shouldn't) learn new languages & where they interpret foreign words as incomprehensible and don't bother trying to comprehend their meaning in context.

think about it this way: an adult who moves to a foreign country for five years not being able to string sentences of arbitrary length together in the local language would be *unusual*, right? yet if a 5-year-old child speaking their first language did so only in simple clauses & stumbled consistently over irregular verbs and conjugations and what have you, you wouldn't bat an eye.

there are some areas of language acqusition where children have an advantage, but in general it's a fairly complex skill that you only get better at with age, and "if you pick up a language after childhood you'll never master it" is a pernicious and illogical myth

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ferengi: Misogyny, Sexuality and Internalised Homophobia

A two-parter! In this essay I'd like to explore and discuss two specific headcanons, and how they are reflected in the display of Ferengi culture throughout DS9:

That Quark is gay

That Rom is genderfluid/non-binary

... and that neither of them have the tools or language to express it.

Part I: Quark is Gay

One element of Star Trek I love is the alien cultures, and the way that through many writers and several decades of work they get built up into complex snapshots of life different to our own, even if they can still be a little Planet of Hats.

Before DS9 the Ferengi were a barely seen race brought up a couple of times in TNG, and always characterised as hyper-capitalist, greedy goblinesque figures. I imagine they were thought up as a direct foil to the Federation: they valued everything the Federation had left behind.

But! Then the DS9 writing team made the decision to bring in Quark, and through him we see so much more of the Ferengi and their culture over DS9's run.

Now obviously the "Quark is gay" theories are hardly new (I mean the show pretty much spells it out with the way he looks at Odo) but I wanted to try and tackle, arguing in-universe, why Quark is closeted even to himself. Firstly, Ferengi culture forbids women from having any place in society except as objects, even more strictly than any real-life culture has ever been. Despite being a spacefaring people, Ferengi women (stated to make up near 53% of their species) are forbidden to own property, run a business, wear clothes in public or exist as individuals divided from their male owners (and they are owned - Quark and Rom discuss Rom's former marriage in one episode, and it's clear that Ferengi marriages are a contract between the father/male 'guardian' and the new husband where the bride is purchased specifically for the role of bearing children).

The only Ferengi women we see in DS9 are - as a necessary consequence - challenging these societal norms. Quark's mother, Ishka, is present in a number of episodes and flouts expectations by wearing her own clothes in public, openly advising on business matters, and later leading the first Ferengi feminist movement! The gif above is taken from S2E07 "Rules of Acquisition" where Quark has to do business with Pel: a female Ferengi masquerading as a male (specifically here using false ears - Ferengi are sexually dimorphic and males have larger ears. One episode indicates they 'shed' them as they grow, meaning it might be a specific male puberty thing).

Quark is a traditionalist. He is, in fact, deeply religious: the Ferengi faith results around the acqusition of wealth so that you can reincarnate into a better life. In essence, it's dharma but with material goods. He resents his mother for her 'failings' (in his eyes) and is horrified by Pel's existence and activities... once he knows she's a woman! He views women as sexual objects for his gratification, and more than once attempts to extort his employees for sexual favours.

But you may argue that Quark isn't gay, because he's only ever shown affection (and overt sexual interest) towards women. He flirts with Jadzia, he flirts with Kira, with Ezri, with all of his female staff and more. But it becomes a little less clear when you get into it.

In S2E07 Pel, still presenting male, kisses Quark in a moment of passion and his reaction is... complicated. He protests, but struggles with it. His discomfort seems less to do with Pel being 'male' and rather his internalised reaction to that. Later still he denies it ever happened! Once confronted with Pel's actual gender he flounders: he realises he has (had?) feelings for her, wants her gone from his life, but also worries about the repercussions if anyone from Ferenginar found out about their business together. Pel leaves at the end of the episode, reconciled to him, and Jadzia comforts the obviously heartbroken Quark. So, was Quark attracted to Pel the male or Pel the female? I would argue he fell for Pel's presentation, and I think there are several more examples of this.

His flirting/borderline/actual sexual harassment of Jadzia and Kira are played off as him being lecherous but... notice something here. These are two women who are very confident, outgoing, public, good at management and business, strong-minded and strong-willed... all traits Feregi culture assigns solely to men. Due to character development his relationship with Ezri unfolds differently (Ezri's definitely enby but that's a different essay...), but his attraction to her lies primarily in his memories of Dax through Jadzia.

To restate the point: he is not attracted to women. He is attracted to women who, in his eyes, act like men.

Then there's the whole... thing with Odo.

This gif, taken from S3E25 "Facets", kinda highlights the whole thing. Odo - merged with the... 'spirit'(?) of Curzon, and containing the personalities and desires of both, grabs Quark by the external erogenous zones and kisses him. Quark and Odo's feelings for one another are very, very gay, although both dress it up in this constant cat-and-mouse game they play. When Odo falls in love with Kira, Quark's the one complaining to Jake Sisko about all the "lonely nights" he "comforted" him. At the end of the series, as Quark puts it:

"Can't you see? That man loves me. It's written all over his back."

Odo, then, is the exception to the above examples: Quark shows a clear affection for Odo, complicated as it may be by their 'professional relationship', but Odo very much presents male.

Well. Sort of. Odo uses he/him pronouns but his actual relationship to gender is left unspoken. I think this is what gives Quark the excuse to open the closet door a little where Odo's concerned.

So why can't Quark just admit he's gay? As I stated above, Quark is a deeply religious, conservative and traditionalist Ferengi (or at least he tries to be... and I think there's something in that, too). There is no discussion of queer identities in Ferengi society, but based on what little of that society we see, I believe that queerness (at least in males) would be strongly discouraged and penalised. Much like real-life homophobia, it would be seen as 'womanly', 'feminine', and therefore undermine what it meant to be a Ferengi (because remember... women aren't Ferengi. A Ferengi with no wealth is no Ferengi at all).

Quark, therefore, cannot be gay, because it would be contradictory to his very sense of self. He's like the gay son of a homophobic evangelical pastor: so deeply conditioned to bury it that he has to act the 'proper' Ferengi despite the fact that he clearly struggles with it. Quark's not as greedy as his peers. He's not as callous or cruel. He has moments of great compassion and kindness, even generosity (which is almost a sin), and, perhaps the strongest piece of evidence to me...

He runs a dinky bar, in a run-down Cardassian space station that until recently was a one-horse town. And he LOVES it. He refuses to give up that bar. He fights for it. When he franchises it at the end of the series, does he move on up to better locations? Nope. He's right there with the dodgy replicators and aging holosuites.

Quark's Bar is his expression of queerness. It's an eccentricity that any 'good' Ferengi would have dumped long ago. Several characters comment on it, and Quark waves them off.

He loves that bar, he loves Odo, and frankly he loves romanticism. Quark is a hopeless gay romantic that, if he ever tried his hand at poetry, would make galaxies weep.

And we love him for it.

#deafmangoes#ds9 quark#star trek ds9#deep space nine#star trek deep space nine#ds9#wow this ended up much longer than I expected#I am apparently passionate about defending queer readings of nineties aliens

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multiexperience Development Platforms Market Growth Analysis & Forecast Report | 2023-2032

As per a recent research report, Multiexperience Development Platforms Market surpass USD 20 Bn by 2032.

Multiexperience Development Platforms Market is likely to showcase growth through 2032 due to the increasing mobile app demand, which has built-in strong traction for touchpoints such as Conversational UI, Location-based services (LBS), Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), multi-touch interactions, and more.

Request for Sample Copy report @ https://www.gminsights.com/request-sample/detail/5531

In addition, the rising demand for machine learning technologies, virtual reality, and augmented reality will offer several growth opportunities for the Multiexperience Development Platforms (MXDP) market expansion. The industry growth is being further influenced by the development of user experience software, wearable technology, and natural language-based software.

Overall, the MXDP industry is segmented in terms of component, deployment, organization size, application, and region.

Based on the components, the services segment will grow considerably from 2023 to 2032. The segmental growth can be credited to the rising need for maintaining the platform, receiving constant updates, and more. MXDP services consist of three main components: tools, an experience management system, and a library of ready-made experiences.

By deployment, the on-premises deployment segment is anticipated to hold a notable market share during the estimated timeframe owing to the increasing need for securing critical data. Besides, features such as enhanced security compared to cloud systems will also favor segment expansion.

Considering the organization size, the large enterprise segment is slated to depict strong growth owing to the increasing deployment of MDXP by large enterprises in view of easing the operation process. Moreover, the rising number of large enterprises in developed and emerging economies will drive the demand for multi-experience development platforms over the forecast period.

Request for customization this report @ https://www.gminsights.com/roc/5531

In terms of application, the IT & telecom industry will garner substantial gains during 2023-2032. The increasing investment by IT and Telecom service providers for developing multi-experience development platforms will favor the segment landscape. Multiexperience expansion platforms offer inclusive solutions for managing the data required in IT and telecommunications sectors via protected and reckless deployment.

Geographically, the Asia Pacific MXDP industry size is projected to surge significantly during the forecast timeline. Expanding industry verticals such as retail and consumer goods, healthcare, IT and telecom, and BFSI will positively influence the regional market outlook. As per the India Brand Equity Foundation, the country's public expenditure on healthcare stood at 2.1% of the GDP in 2021-2022.

Partial chapters of report table of contents (TOC):

Chapter 2 Executive Summary

2.1 Mutliexperience development platforms industry 360° synopsis, 2018 – 2032

2.2 Business trends

2.2.1 Total Addressable Market (TAM), 2023 - 2032

2.3 Regional trends

2.4 Component trends

2.5 Deployment trends

2.6 Organization size trends

2.7 Application trends

Chapter 3 Mutliexperience Development Platforms Market Industry Insights

3.1 Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

3.1.1 North America

3.1.2 Europe

3.1.3 Asia Pacific

3.1.4 Latin America

3.1.5 MEA

3.2 Russia-Ukraine war impact

3.3 Industry ecosystem analysis

3.3.1 Platforms providers

3.3.2 Service providers

3.3.3 Technology providers

3.3.4 System integrators

3.3.5 Profit margin analysis

3.4 Patent analysis

3.5 Key initiative & news

3.5.1 New product launch

3.5.2 Partnership/collaboration

3.5.3 Merger/acqusition

3.5.4 Business expansion

3.6 Technology & innovation landscape

3.7 Regulatory landscape

3.7.1 North America

3.7.2 Europe

3.7.3 Asia Pacific

3.7.4 Latin America

3.7.5 MEA

3.8 Industry impact forces

3.8.1 Growth drivers

3.8.1.1 Rising need to create rich and interconnected user experiences

3.8.1.2 Increasing investment on MXDP

3.8.1.3 Rising need for low code application development

3.8.1.4 Increasing demand for touchpoints

3.8.1.5 Rapid adoption of advanced technologies

3.8.2 Industry pitfalls and challenges

3.8.2.1 Limited number of devices MXDPs support

3.8.2.2 Maintaining MXDP platforms

3.9 Multiexperience development platforms use case

3.10 Multiexperience development platforms architecture

3.11 Growth potential analysis

3.12 Porter's analysis

3.13 PESTEL analysis

About Global Market Insights:

Global Market Insights, Inc., headquartered in Delaware, U.S., is a global market research and consulting service provider; offering syndicated and custom research reports along with growth consulting services. Our business intelligence and industry research reports offer clients with penetrative insights and actionable market data specially designed and presented to aid strategic decision making. These exhaustive reports are designed via a proprietary research methodology and are available for key industries such as chemicals, advanced materials, technology, renewable energy and biotechnology.

Contact us:

Aashit Tiwari

Corporate Sales, USA

Global Market Insights Inc.

Toll Free: +1-888-689-0688

USA: +1-302-846-7766

Europe: +44-742-759-8484

APAC: +65-3129-7718

Email: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

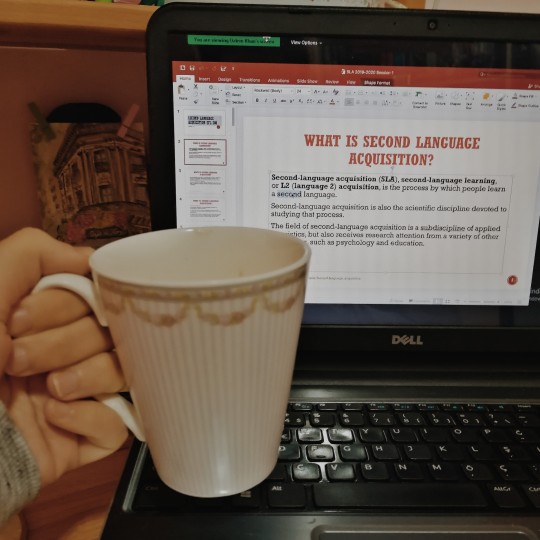

• zoomester studying challenge •

15/100 days of productivity

hello beautiful people! i hope you're safe, happy, and healthy. today's been a busy day, so here are the things i've done so far:

• i studied futurism, lettrism, surrealism.

• prepared my plan for this week.

• attended my language acqusition class.

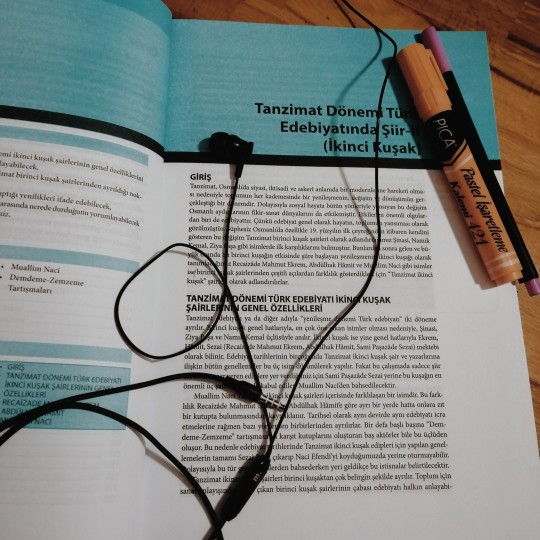

• attended an online presentation on women's voice in modern turkish literature. it was so good and i learnt so many new woman writers and poems, and their works i've never heard before. the professor who presented it was also so cute and nice. i really enjoyed it!

• i'm now studying poetry in tanzimat reform era.

day 8- international women’s way! what’s your take on feminism?

i think feminism is very misunderstood: so many people think it's about hating men. since i was 14 or 15, when i decided that i agree what feminism defends and is about, i've been trying to inform and explain people that feminism is about equality. it's not about hating men or ignoring their problems. anyways, i think everyone should learn what feminism is actually about because then, they'll see it actually defends rights and demands equality. i love feminism and proud to call myself a feminist because as a person who lives in turkey, i know we need feminism. i know being a feminist and demanding and defending women's rights are so important. i'll always defend women's rights and demand equality. and when i say women's rights i mean each and every woman. trans women, black women, turkish women, women with disabilities, shortly, women all around the world. and happy international women's day! thank you to all women in my life! ♡

take care, good luck, and may it be easy!✧*。

#zoomester studyblr challenge#studying#studyblr#studyspo#studystudystudy#study blog#student#study motivation#studygram#studyinspo#study aesthetic#study hard#study notes#studying aesthetic#100 days of productivity#study area#study space#study desk

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acqusition

Acqusition

by shadowgirl1130

Sabine and Tom enlist Chat Noir to find Marinette who has gone missing.

Words: 7482, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English

Fandoms: Miraculous Ladybug

Rating: General Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: F/M

Characters: Marinette Dupain-Cheng | Ladybug, Alya Césaire, Adrien Agreste | Chat Noir, Gabriel Agreste | Papillon | Hawk Moth, Sabine Cheng, Tom Dupain

Relationships: Adrien Agreste | Chat Noir/Marinette Dupain-Cheng | Ladybug, Sabine Cheng/Tom Dupain

Additional Tags: Marichat | Adrien Agreste as Chat Noir/Marinette Dupain-Cheng, Marinette Dupain-Cheng | Ladybug Identity Reveal, Identity Reveal, Chat Noir/Marinette Dupain-Cheng Fluff, Adrien Agreste | Chat Noir Identity Reveal, Bad Parent Gabriel Agreste, Gabriel Agreste | Papillon | Hawk Moth Identity Reveal

Read Here: https://archiveofourown.org/works/32766718

#AO3 Feed#FanFiction#AO3 Marichat#💚#🐱#💖#Marichat#Miraculous Ladybug#♥#R:G#A:Shadowgirl1130#Reveal Fic

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

I have to share it - it’s my favourite language acqusition theory! It feels so natural, so obvious - yet so surprising! In my opinion, not only every language student, but also every language teacher should read it.

Also, if someone is learning Portuguese, this site has the portuguese version of the article!

#langblr#language learning#language learn#how to learn language#stephen krashen#language#acquisition#language acquisition

13 notes

·

View notes

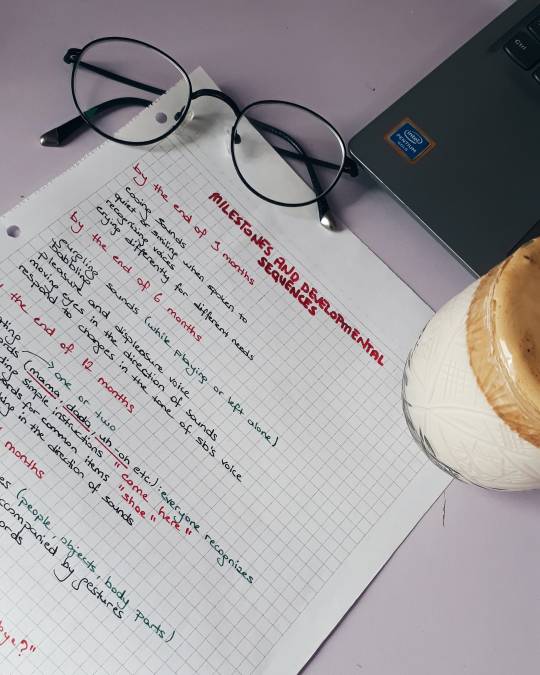

Photo

failed dalgona coffee tries and language acqusition notes

follow my studygram here!

#my-posts#study#studyblr#studyspo#study tips#studying#blog#coffeee#notes#language acquisition#studygram

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

🖖 - What symbols are prevalent in their society? (colors, shapes, hand gestures, icons of heroes/leaders/stories, etc)

So, to answer this I’m gonna focus on a subculture I ADORE writing about.

The Ethereals.

for them, arcanic symbols are as common as the alphabet, as well as that of contracts and transactions. The two driving forces of ethereal culture is finance and power acqusition. So they reflect those in their language and their priorities, barring the open corruption that surrounds those such as the Ethereum.

Their gestures are often simple, focusing on a lack of touch in order to sign agreements or commend each other in a positive manner.

1 note

·

View note

Text

First Language Acquisition and Child Speech

First Language/Native Language Acqusition

Our native languages surround us from birth. Babies start acquiring them as soon as they start crying, and then cooing (usually around six 6 weeks). Babbling ("mamamama, dadadadada") doesn't generally start until around six 6 months. Language acquisition occurs fastest around the age of two 2 years, when a child learns most at once.

Most children pass language milestones at similar ages. However, some children pass some milestones earlier or later than others. Even so, they pass milestones in the same order as most other children.

Babbling (6-12 months)

More or less all babies babble, even Deaf babies (with some exceptions). In the earliest stages of babbling, babies will use sounds that aren't part of their native languages' systems, as initial babbling comes from the baby, not from the baby's linguistic environment (the language(s) being spoken at home).

Babbling becomes specific to a hearing baby's native language between six 6 and twelve 12 months. After this, a hearing baby will only use sounds that are found in their native language(s). At this stage, Deaf babies will often stop babbling. However, if their caregiver uses a sign language, a Deaf baby will often start babbling in that sign language, repeating particular signs where a hearing baby would use combinations of vowels and consonants.

At the babbling stage, a baby will say, "Mama," "Dada," "Baba," and "Papa," which is why words with these sounds are used for parents in lots of languages; they're sounds that stick to a particular figure in a child's life, often present in the earliest stages. Parents tend to reinforce this by referring to themselves in the third person when talking to the child, e.g. "Do you want Mama/Papa to read you a book?", "Dada's taking you to the park this afternoon."

Holophrastic/One‑Word Phase (12‑18 months)

In the holophrastic phase, a child will begin to speak in individual words. At this stage, these words are used in the places of whole phrases (holo‑=whole, ‑phrastic=phrase), and their meanings can vary with context, as well as from child to child.

"Milk" may really mean "I like milk," but it may also mean "I want milk," or "I don't want milk," or "Have some milk." You really need to know the child and the context well in order to understand properly.

At this stage, children may also overextend the meaning of a word, so that "milk" refers to all liquid. Meaning may also be underextended, so that "man" only refers to the child's father, and "dog" only refers to the family dog; other dogs aren't called "dog", and other men aren't "man".

A child may also pronounce words differently in the holophrastic phase, contracting consonantal clusters like "pl" [pl] into "p" [p] or "l" [l] to make "plum" into "pum" or "lum".

Combining the different pronunciation heard in the holophrastic speech with the overextension/underextension of meaning, and the use of single words in place of phrases, "lum" might be a child's way of saying, "I would like a plum" (whole‑phrase speech and consonant contraction) or even "Where is the fruit bowl?" if the child overextends "lum" to mean all fruit, not just plums.

Two‑Word Stage (18‑24 months)

The two‑word stage is present in the acquisition of more or less all first languages. This stage is similar across different languages, and all children will use the right syntax (word order) for their native language.

Japanese and Korean word order is Object‑Verb ("store go"), and English word order is Verb‑Object ("go store"). Children acquiring their first languages get syntax right automatically, and don't have to sit down and learn it like in a second‑language lesson. They observe speakers around them, and mimic their syntax. Grammar is usually missing at this stage, but word order is usually accurate.

At this stage, auxiliary words (such as "will" in "I will go", "to" in "go to playgroup", and "can" in "can I go?") are omitted. So are articles ("the", "a/an", etc.) and pronouns ("she", "him", "their", "your", "we"). Therefore, an English‑speaking child between 18 and 24 months will say "go store" rather than "I will go to the store".

Semantics at this age are very simple. A child at the two‑word stage won't have a large vocabulary, so will call all shades of blue "blue", rather than specifying "turquoise" or "cerulean" etc. They might not distinguish between "cat" and "kitten", "walk" and "crawl".

Telegraphic/Multiword Stage (24‑30 months)

This stage is also called the telegraphic stage because children speak as if they're writing a telegram. This is because 24‑30 month‑old children don't use auxiliaries. They say things like, "I want go park" when they mean, "I want to go to the park". Little grammatical words are missing, like they are in a telegram. Only words that carry real meaning are used; sentences can still be understood, but an adult will think of them as having gaps.

Gradually, a child at this stage will start adding functional words, such as pronouns, as well as inflections (for the ends of words), like "‑ing" and "‑ed", so that "Holly walk" becomes "Holly walked" and "Joey swim" becomes "Joey swimming" (to mean "Joey is swimming").

Complex sentences (30+ months)

Complex sentences have two clauses, e.g. "I know that she likes toffee" and "This is the bus which broke down yesterday". Children will start to produce these sentences from about 30 months.

Questions and negative statements are grammatically complicated, so many children still struggle with them at this age. "Where has she gone?" requires the inversion of "she has" as seen in "she has gone." "I don't like peas" requires the auxiliary "do", which the positive "I like peas" doesn't. Most grammatical structures like this will be in place by the time a child reaches three 3 years, so having a child older than that speak in telegraph or holophrase will seem odd to a reader unless there's a reason for it, explained in the story. Most children won't speak in telegraphs past 30 months.

At this stage, some children will still have trouble with irregular past tenses, saying "I swimmed" instead of "I swam", and "I runned" instead of "I ran". However, they're not likely to confuse "I swim" with "he swims" and say "I swims" or "he swim" at the complex sentence stage.

Children hypothesise rules to produce words and sentences that they could never have heard. They might overregularise language, hearing "happy/unhappy" and assuming they can also say "sad/unsad", or "fat/unfat". A child might hear "can you butter my bread?" and produce "can you jam my bread?", because they think that "jam" can be a verb in this context, as "butter" can.

Correcting Grammar

Linguistic input has an important role in first language acquisition, but direct teaching or covert correction by adults is generally fruitless unless the child is cognitively ready to understand what's being said to them. You can't teach a two-year-old how to make questions or relative clauses, because they're not old enough to understand your corrections.

For @sins-virtues and @givethispromptatry

From university lecture notes, organised by Hilary Hale, AKA @thorlokibrother.

#writing reference#writing ref#ref#reference#writing children#child speech#first language acquisition#linguistics#langblr#writeblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

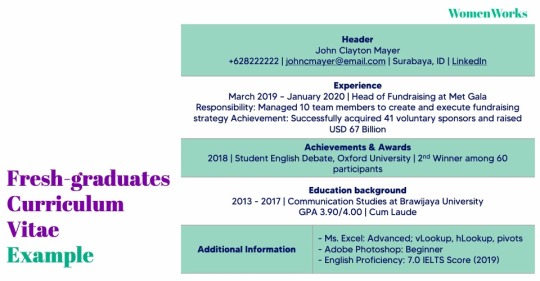

How to stand out from the rest?

Masih dalam rangka #MasterClassBootcamp hari ini ada kelas dari @womenworks dengan topik “how to stand out from the rest?”

Sesi kali ini diisi sama Sarah Fatikasari, a Talent Acqusition di nestle, dia hobi sepedahan suka the beatles dan John Mayer, daaaaannn She owned A band WUHUUU SHOOO COOLLL. Bandnya namanya bythetime, terus ku dengerin salah satu lagunya di spotify, ena ~

ini diaaa langunyaa

*brb beli bass, eh asli tetiba kok pengen main bass ya, setelah gagal les drum lol*

Basically sesi ini membahas tentang gimana bikin CV yang baik, tentunya ini sangat relevan sama posisi kak sarah saat ini, dia juga sering ngebagiin informasi di Instagram tentang recruitment process pake hastag #sarahbraindump.

Nah tapi kenapa sih sebenernya kita perlu bikin CV, kenapa ga langsung aja gitu ngasih transkrip ama certificate? Ini dia jawabannya

Companies hire the ultimate match, dan untuk tahu match atau tidak, kita perlu define our values dan contribution dengan baik supaya mereka punya informasi yang lengkap untuk kemudian bisa dicocokkan dengan company attributes and job qualifications. Tapi selain well defined, juga perlu di filter juga nih, skill unique apa sih yang kita punya, yang match dengan qualification, karena itu lah yang bikin kita bisa stand out from the rest. Jadi, costumize CV juga jangan lupa, jangan make satu CV untuk kemudian di pake di banyak job apply, that’s weird!

Nah kalo udah tau kenapa penting untuk bikin CV, harus tau juga dong CV yang baik tuh yang gimana? yang punya design menarik? atau yang polos? yang pake poto bikini? pose sebat? atau roll depan?

Tentunya pakailah poto yang mukanya kaya ariel tatum, kalo gada, gausa pake poto, canda gaes.

Jadi sebenernya kalo banyak yang bilang bikin CV tipe kreatif atau polosan itu tergantung dari company nya seperti apa, tapi sebenernya ngga juga. Mostly orang mikir bahwa start up company lebih milih orang yang kreatif, tapi creativity itu ngga harus ditunjukkan di CV loh, bisa attach di portfolio, misal kalo yang jago design bisa melampirkan link behance nya, dsb. Jadi kesimpulannya pakai yang polos tapi ngga literally polos, sebisa mungkin orang yang baca punya reading experience yang structured. Tentunya ngga itu doang dong ketentuan bikin CV yang baik, oke baik, ini dia detailnya.

Nah kalo udah tau cara bikin CV yang baik, perlu tau juga nih struktur isi CV tuh apa aja sih?

Header

- Full Name

- Phone Number

- Email

- Current City

- Linkedin

Experience

- Key dates

- Your role

- Company/ organization/ project name

- Key responsibilities

- Key achievements

Achievements & Awards

- Year

- Organization

- Scope of achievements & award

Educational background

- Year

- School Name

- Major

- GPA

- Predicate if Any

Additional Information

- Language profeciency

- Other measurable skills

- relevant interest

Contohnya kaya begini nih.

Nah kalo udah tau CV yang baik kaya gimana, harus tau juga nih CV yang buruq tuh kaya begimana, ada beberpa tipe CV yang buruk yaitu :

Details are not indicated completely

Incorrect experience orders, inget! dari newest role ke oldest role

Language Inconsistency, Typo, Grammatical Errors

Unmeasurable skills and languange charts, harusnya sih jangan pake chart, harusnya pake scale kaya gini

- Length of experience : 3 years HTML coding experience

- Qualifications and training : Microsoft-certified, 2012

- Scale of task : Led a team of 5 in the management

- Languange proficiency : Beginner/ Intermediate / Advanced in bla bla

Size of file is larger than 2MB

Nah dari beberapa list kesalahan CV itu ratingnya kaya gini,

Oke sekarang CV udah oke nih, perlu ngga sih bikin cover letter?

Jawabannya perlu, kenapa perlu?

Ilustrate your key skills and how they will add values to the company once you are successfully hired.

Prove how extensive your research about the company

Showcase your writing skills - can be used to answer pre-screening essay questions and body email

Express your personality through story telling

Cover Letter yang bagus tuh yang kaya gimana?

Strong WHY you interested to the job

What experience makes you IDEAL for the job

RELEVANT skills that you can bring to the job

Sekian dan trimakaziiii, so fruitfull session of tudei’s class. Also got a short of positive energy from womens in the class :))))))))))

0 notes

Text

Transcript Lingthusiasm Episode 10: Learning languages linguistically

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm Episode 10: Learning languages linguistically. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the Episode 10 shownotes page.

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that's enthusiastic about linguistics. I'm Gretchen McCulloch,

Lauren: and I'm Lauren Gawne, and today we'll be talking about how learning a language is a way of giving yourself great linguistic skills. But first, Gretchen, you sound amazing!

Gretchen: Thank you! You're hearing me on this new microphone, actually a recorder, which is thanks to our lovely patrons who have enabled us to buy this microphone. Lauren, how is it that you always sounded so good?

Lauren: It wasn't just sheer, natural magic, it's because I have been using, since the beginning of the podcast, an audio recorder called a Zoom H4N, which -- the H4N Zoom have a slightly newer model as well, but these recorders are kind of linguist-famous for being reliable, solid recorders, especially for doing things like fieldwork, so I've had one for quite a few years to do my linguistic fieldwork with, so if you listen to any of my recordings from Yolmo or Syuba or any of those in the archives that I have, they're made on this very same recorder and so that's why I've always been able to sound good without us needing any budget for that. But now we're twinsies, and you have a Zoom H4N as well.

Gretchen: So now I have a matching one. They're friends.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: They haven't met yet, but that's okay, they're going to meet in audio heaven, so that we will sound the same audiowise and so that I can learn how to use it from Lauren and we're going to sound really good, so that's exciting!

Lauren: Yeah, and a big thanks to our patrons for that.

Gretchen: Yeah! And it is thanks to people on Patreon that we were able to make this possible and keep doing that, so that is really exciting. Also, they get to listen to bonus episodes and this month's bonus episode is about hypercorrection.

Lauren: Bonus episodes will also sound amazing because they're all on the shiny new recorder as well.

Gretchen: Yes!

Lauren: As you said, our current one is hypercorrection, but we also have a whole bunch of other bonus content and you can get all of it if you become a monthly supporter of the show.

Gretchen: On patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website/social media. And by the time you're listening to this, I will also be in Kentucky at the Linguistics Summer Institute, or Lingstitute as we like to call it, and we are recording this in advance because we're organised like that, but that will be having lots of stuff going on.

Lauren: 'Cause you're going to be a bit busy.

Gretchen: Ha, I'm going to be really busy -- that'll have lots of stuff going on on the Lingstitute hashtag, which we can link to, and as well my class at the Institute -- I'm going to be teaching a class on linguistics communication, linguistics outreach, how to be better at explaining linguistics and bringing linguistics to more people -- and so we're going to be using the hashtag LingComm, that's LingComm with two Ms as in communication --

Lauren: Awesome.

Gretchen: -- and so you can follow those as well if you want to follow along with the class and see what we've been up to.

Lauren: I will definitely be doing that.

Gretchen: Lauren is going to be, like, co-teaching the class from afar, she doesn't know it yet, but she's going to be like, "Hey, go support my students!" [Music]

Lauren: So, Gretchen, you're a linguist. How many languages do you speak?

Gretchen: That's a good question! That is a question that a lot of linguists get, a lot of the time.

Lauren: It's a question that a lot of linguists get -- it's a little bit annoying because it misrepresents the idea that linguistics is just about learning lots of languages, but independent of being a linguist, you'll find that people who study how language works are often interested in learning other languages as a way of kind of getting an understanding of how they work.

Gretchen: Yeah, and I think for me, because -- at least personally, the way I got into linguistics was in high school, I came across pop linguistics books and stuff like this, and I was like, "Wow, this is so cool, I want to do this when I get to university." But I knew that I couldn't do it in high school, there's no high school linguistics course that I could take then -- they're still very rare in high schools -- and so I said to myself, "Well, I know it's not quite the same as language learning, but I'm going to at least enrol in all of the language classes that I can because I'm sure it won't do any harm. And, you know, I could be learning about cell biology or something, or I could learn more languages and I think the language would be more useful," and I think they were for me. I mean, cell biology's fine if you're into it, but like...

Lauren: So what languages do you have experience of learning?

Gretchen: So, I started learning French in grade four when I was in school, because that's the latest age you can learn French in for Canadian schools. It would have been nice to learn it earlier, but that wasn't offered. And then I did a Scottish Gaelic summer camp when I was like 10 or 12 or something? I went to Cape Breton and I spent a week learning Scottish Gaelic. Everyone else was there to learn, like, fiddle and step dancing and stuff and I was like, "I'm just going to take all the language ones." I don't remember a whole lot of that, except for the fact that they put the verbs at the beginning of the sentences, which is really neat, and I have a couple songs memorised from that, so that's fun. So I can occasionally sometimes do something with a song. But I didn't really know much about grammar except what I'd learned from French at that point, so I didn't have a lot to hold on to there.

Lauren: Yep.

Gretchen: I also mostly self-studied Latin in grade 10, because again, I was interested in linguistics, and at that point in my mind, linguistics and Classics overlapped a lot, and the history of grammatical descriptions of English is very bound up in Latin. So I was like, clearly, this is the thing I need to do. So I got myself a Latin textbook and worked through all the exercises.

Lauren: Of course! This is a very good insight into how Gretchen's brain works there.

Gretchen: And then in grade 11 I convinced my guidance counselor against his better judgment to let me take both Intro Spanish and Intro German and continue my French --

Lauren: Right.

Gretchen: -- because I was like, "Look, I'm not picking between these."

Lauren: That's a lot of language.

Gretchen: That was a really interesting experience, because one day, I remember, in German class we did numbers and then I went to math, and then in Spanish class an hour later we were doing numbers and I was like, "I can't... handle this..."

Lauren: Right, yeah, challenging.

Gretchen: But it really taught my brain. I really convinced my brain that there was more than one other language than French.

Lauren: Yup.

Gretchen: 'Cause this is a problem a lot of people run into you when you're learning another language is that you're like, "Okay, I have my native language and then I have, like, every other language" and they just blend into each other too much."

Lauren: Ah, that is how my brain is organised, definitely.

Gretchen: I have to say, if you really want to convince your brain that there are multiple languages, learning them all in parallel is one way to get that. It's not pretty at the time, but it has been very persistent! Yeah, so then in undergrad I was trying to do about one new language a year for about eight years or so. So in undergrad I took Ancient Greek for a year and then I was like, "I'm doing too many European languages this is ridiculous," and so then the next year I took Arabic. I took that for two years and then wrote my honours thesis about Arabic.

Lauren: Yep.

Gretchen: And then I did a field methods class on Kinyarwanda, which is a Bantu language spoken in Rwanda. And that was really interesting, but I learned more about that from kind of the linguistic side than from the conversational side.

Lauren: Yep.

Gretchen: I only remember a few words. And then I took Italian just for fun, because I needed to fill an elective.

Lauren: You needed to fill in your romance paradigm.

Gretchen: Yeah, I needed -- I was like, I feel really incomplete in the romance languages! I still have never learned Portuguese and I don't know if it would be a good use of time, but there's a part of me that wants to, just to fill it in. Yeah! And then I got to grad school, and then in grad school I did a field methods class in the first semester on Mi'kmaq, which is an Algonquian language located in Eastern Canada, and then I kept on working with that language and the language teaching classes and stuff for the rest of my degree and for my thesis. So yeah, that was kind of when I stopped learning a new language every year.

Lauren: Fair enough!

Gretchen: But I had a really good run of it!

Lauren: Yeah!

Gretchen: And the European languages got easier and easier as I kept learning more of them. The non-European languages were each their own unique challenge, as far as the grammar went.

Lauren: Right.

Gretchen: Yeah, so I have a pretty extensive language learning history and I definitely don't remember all of these, so obviously the question of "What do you know, what do you speak, what do you learn?" is always one that comes up when you're talking about speaking lots of languages. But I did spend a lot of time in language classes.

Lauren: Yeah, fair enough.

Gretchen: What about you? You speak some languages.

Lauren: I kind of lumped my language learning into three different phases of my life. So, the first exposure I had to language learning was in primary school. My primary school taught Italian, but by "taught Italian" I mean in this very Australian -- Australia is, like, upsettingly proud of its monolingual educational focus, I think, so a lot of schools do some amount of language learning, but there's no real understanding, or nothing imparts to students why you might be learning this or why it might be interesting to care about another culture or a language, and so I learnt lots of random Italian vocabulary and some songs in primary school and at the start of high school. And then when I changed schools halfway through high school, no one felt at all compelled to encourage me to keep going with Italian or to take up one of the languages at that school, and I didn't really understand the idea of learning languages. Everyone in my family day-to-day spoke English, everyone in my social life day-to-day spoke English, and other countries and languages just seemed really far away. So that was kind of my early, underwhelming language exposure. Does mean I can navigate an Italian menu quite well sometimes, but not much more.

Gretchen: Yeah, I mean, I guess for me in Canada, the French thing was, "Well, you should stay in French because it'll help you get a job later." Because if you want to work in tourism, or if you want to work for the government, it's useful to be able to speak French. So it was very kind of, like, mercenary-focused around learning the language.

Lauren: And also being in Canada, like, even if you're in an English-speaking province, you're exposed to this idea that French is a language in the wild, like it's on your groceries when you buy them and it's in the news --

Gretchen: Yeah.

Lauren: -- kind of thing.

Gretchen: Yeah.

Lauren: So then after high school, I went to live in Poland for a year and that was interesting, because my grandmother's Polish and it's her first language and so I was interested in kind of reconnecting with that and also kind of just living somewhere different and doing something different. And that's my period of, like, understanding the motivation for language learning, but it was before I'd done linguistics or really had any good role models for language learning and so I became pretty competent, but I missed out on a lot of things that are kind of considered good practice for becoming a strong second language learner. So I was having some lessons, but I wasn't always good at kind of encouraging myself to speak to people in certain contexts, and so I really enjoyed doing that, but when I got to Australia there weren't many opportunities to continue that. And for some reason I think I was so annoyed about that when I started university that I never took up a language course.

Gretchen: I took, like, all the languages, I was like, "Oh, I can finally take other languages!"

Lauren: I really don't understand what 19-year-old Lauren was thinking, but I'm really thankful that she took linguistics, because obviously I've been pretty enthusiastic about it ever since. And that kind of led to my third era of language learning, which has been kind of understanding, like, post- studying linguistics, understanding my own motivations and practices and behaviours in language learning, and since then I've learnt Nepali, which I use in kind of day-to-day interactions when I'm on fieldwork, and Nepali is great because it's an Indo-Aryan language, so it's part of this larger Indo-European family, so it's not too hard for me to get my head around in terms of the structure, but it does some really cool, nifty things with the grammar. And I've also learnt -- to varying degrees, not as well -- a couple of different Tibetan dialects that I've worked with. I would say my competency there is more what we call passive competency in linguistics. So, I can understand a lot of things that are said to me, I often can't reply that speedily or I end up just falling back on Nepali. And then I've also been learning some Auslan at various points while in Australia, which is the Australian sign language. It's related to British Sign and New Zealand Sign Language, and now that I've moved back to Australia I'm really looking forward to getting back into Auslan. And that's been really great because it's completely unrelated to my study, I just really enjoy it. So that's kind of a whirlwind tour of my --

Gretchen: And it's related to your research in the sense that you do gesture, and so having a better understanding of sign probably helps you with gesture research? I don't know, I'm making this up.

Lauren: It helps with my gesture research, but, you know, I think as a linguist I can kind of make the excuse that any language learning is helpful for my job to some degree, but I also just love Auslan and learning a sign language is a really fun change from spoken language to a sign language is quite good for my brain, and it does get less chatted up with all the random bits of Italian and, you know, café French.

Gretchen: I never had the opportunity to learn sign language, although I'm sure I could find lessons now. If I was going to learn another language it might be either ASL or LSQ, which is Langue des Signes Québécoise, and I'm not quite sure what the relative linguistic situation there is about, which one is spoken more in Montreal, but yeah. I knew a linguist who could speak Mayan and was learning ASL and was like, "My brain is trying to do Mayan structures in ASL and it's the weirdest thing."

Lauren: Oh, that's great, that's so good.

Gretchen: Yeah! So, I don't know if that happens everybody, but I guess some people do get that kind of cross-modal transfer. For me, the question of, okay, how many languages do you speak is, I can answer that, but I feel like I'm kind of letting down the team in that case because I don't speak a lot of them terribly well, and I think for me one of the things that changed was when I started learning non-European languages, I mean the grammar was very different, but also the kind of cultural context that you come into learning those is a lot different. So, you know, as an English speaker, learning French, particularly in Canada where they're both official languages and so on, that's very different from being either an English- or French-speaker in Canada learning a Canadian indigenous language where, you know, indigenous languages aren't on the cereal boxes.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Where they aren't being taught in schools from a very young age the way English and French are.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: So I think becoming more aware of kind of the colonial context in which language learning and denying people the opportunity to learn their language is a bigger issue that I became more aware of.

Lauren: I grew up in Australia on Bunurong country and that is a language that is now taught in some primary schools around that area, which makes me so happy and I wish that was a thing that happened when I was a kid. There is a lot of complexity around, you know, language ownership, especially in the Australian context -- who is allowed to learn a language and which parts of a language -- it doesn't operate the same as, say, English or French or Italian where you can hand someone a textbook and they kind of have the right to speak the whole language. So there's an imbalance there, and there's also just -- same in Australia as in Canada -- that historical imbalance of who is expected to learn whose language.

Gretchen: Yeah, exactly, and if you say, like, okay, well, my ancestors are the ones that were preventing their ancestors from learning the language in the first place and now I want to come in and I've decided it's cool, like, that's a weird position to be in.

Lauren: And there's also a bit of a problem in Australia with heritage languages. So as I mentioned, my grandmother is a native Polish speaker and out of all of my aunts and uncles and my cousins, I'm the only one who speaks or, more likely, spoke that language with her to any kind of degree of competency, because in Australia there's this erasure, often, of people's migrant languages and their linguistic experience. And she was told to never speak Polish, or, she's also a fluent German speaker, and was told to not speak either of those to her own children because it would interfere with their English. And those attitudes are kind of changing...

Gretchen: Yeah, I think it's the same here, though a lot of people, at least -- I'm not sure so much about people who came over in like the '60s -- you get this kind of generation that immigrates, speaks their language, they learn English, and then their kids grow up and they're kind of more or less bilingual, and then the grandkids only really speak the dominant language.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Depending on the community, some of them try to retain their heritage language more -- they'll send their kids to Chinese school or Hebrew school or something on the weekends to try to have them retain that connection to their heritage language, and some of them don't have access to those schools, or don't feel the pressure to do that, so it depends on the community, but there's a lot of language loss. And I think that's something else that doesn't come up so much in language classes, is there's this sense when you go into a language class that you walk in and then you're starting with zero knowledge and you're going to have the knowledge, like, spooned into you the way that when you walk into a math class, you don't know any math, or when you walk into a science class you don't know what a cell is and you just have to get that told to you and then you know.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Whereas for kids that are coming from a heritage language context, they may know some stuff, and there may also be a lot more guilt about not knowing this stuff, or feeling like you should already know it, which you don't get so much, like, I didn't run into that learning French or something.

Lauren: And there's also a kind of prestige thing about learning certain languages as certain communities, and so a lot of English-dominant or English-monolingual parents might see a lot of prestige in sending their child to a bilingual English-French school because French bilingualism has this prestige status, but then we have these children who come in who are amazing bilinguals in, say, Vietnamese and English, or, in Australia we have a lot of indigenous children who are Kriol speakers, so that's a language that has a lot of English words that have created it, but it is its own language, or they speak a variety that's called Aboriginal Australian English. So they speak these varieties and then they come into school and they're in a similar position where they're bilingual or they're trying to become English speakers as well as Kriol speakers. Even though there are, you know, many cognitive benefits that people discuss in relation to multilingualism, there's not the social prestige and there's a lot of issues with getting people to accept that these children need additional support to move towards being full bilinguals and so that kind of thing, when you're kind of just signing up for your undergraduate Spanish class or you're taking Japanese or Arabic or some of the global languages, you can often not be aware that there's a lot of social prestige and a lot of good fortune to just be able to do that.

Gretchen: And I think also that our expectations are different when it comes to rolling up to a college-level language class and spending a couple semesters learning Japanese or Spanish or something, like, "Oh, now I kind of speak this!" And you can -- you know, you passed the test but if you go there you can barely do greetings. Whereas, if you have someone who speaks a different first language at home coming into an English-dominated school environment, that's gonna be a very different situation because they're now going to be expected to function at the same level as these kids that have all of this English at home as well. It's not just like, "Oh, I can say a few greetings and read menus and signs now and now I speak this language," it's -- you're not functioning completely 100% like a native English speaker, like you're doing something wrong, and like who we value bilingualism coming from.

Lauren: Yeah, and also what the motivation for people to learn a language is. So for a lot of people, to learn English is increasingly considered a kind of economic necessity to move forward in life. Like, when I was in Nepal, for me, learning Nepali was a great way to connect with people, it's a way to allow me to do my job, but no one is forcing me to learn Nepali in my family to improve my economic outlook or allow me to work overseas, whereas a lot of my friends are really struggling to learn English and and feel like they are obliged to learn English to have a more secure economic future and that's, like, it's such a gulf in expectations. And you know, if I didn't speak Nepali I would probably still get by day to day in Nepal because so many people can accommodate my linguistic needs and so many people there speak an amount of English now to get by day to day, and they're massively different motivations.

Gretchen: And something else that you run into, I think, in English-speaking areas is that, like, English is a lingua franca, so even people who don't speak the same first language, they all speak English as a second language. And in those contexts, sometimes the native English speakers can be the ones that speak too quickly or use too many idioms or aren't paying attention to doing the comprehension checks that you do if something's your second language, and so you have a kind of global English and you have a kind of too quick English, or too nativised English as well in some of those contexts.

Lauren: Yeah, I think -- and this is something you have a post on, about learning second languages -- like, learning other languages has made me far more tolerant and understanding of people who have different levels of English speaking.

Gretchen: For me, being able to say, oh, okay, so this person's English is around the level of my French, which makes me able to say -- I'll only say things in English to this person that I could say in French.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Or this person's English is around the level of my Spanish. My Spanish is much worse than my French, so now I'll only say things in English that I could say in Spanish.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: And to be able to kind of put myself in the shoes of what do I find useful if someone's trying to do a comprehension check with me, you know, it's not just a matter of talking louder, but sometimes it's a matter of articulating a little bit more clearly, or a matter of saying something two or three times in the same sort of way. Yeah, figuring out, like, what do I appreciate when someone is doing for me in a second language and how can I do that if I'm talking to someone who's less fluent in English, I think is one thing -- I think another thing that comes up for me with second language speaking is there's a big rupture between the classroom experience of learning a language and the real-life experience of speaking a language that you're less fluent in.

Lauren: Oh my gosh, so much.

Gretchen: Let's pause it and think about how big that it is, right. Like, there's a lot there. And you can be, like, a straight-A student in your language classroom, or you can get all of the -- check off all of the things on Duolingo or Rosetta Stone or one of those, and tick all the boxes and yet when it comes to speaking, you're like, "Uhhh..."

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Or you don't even want to let on that you do speak any of the language because it's so terrifying.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: How have you dealt with this?

Lauren: Well, I consider myself pretty articulate in English and I've just kind of had to accept that I'm a different person in Nepali because I just don't have the same linguistic repertoire that I have in my native language, and so in Nepali I'm a very quiet person, I do a lot of listening and I make really bad jokes about my poor language to kind of offset the fact that my language is really poor.

Gretchen: Yeah, yeah, you become kind of more willing to laugh at yourself.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: To compensate. I think for me, yeah, I'm less verbally dexterous in French; I'm pretty fluent in the sense of doing stuff, but it's harder for me to make just kind of idle small talk.

Lauren: Yup.

Gretchen: Like, beyond one or two stock -- I have one or two stock things, but if I'm trying to make casual conversation about something, I don't always have those words, so maybe that's just not a kind of conversation that I'm currently able to have in French.

Lauren: So I think the big difference for me between learning Polish and learning Nepali is that I just -- even though my Nepali was atrocious when I first turned up in the country, I made a point, even with people who spoke English, to make our day-to-day social interactions in Nepali. And it was horrific for everyone and it was exhausting for the first little bit, but in a way I've benefited because there were all these relationships that I now have that I had so much more Nepali practice, whereas in Polish, because my language was really poor when I arrived, a lot of my initial relationships and friendships that I set up were in English and that kind of set the tone for those. So I've learnt to use that doggedness about just kind of sticking with it even though I've only got like three sentences' worth of interaction to have, but it is really exhausting. And it's the benefit of being in the country.

Gretchen: Yeah, I found this -- so I live in Montreal and when I moved here, I had, my whole life, this cautionary tale that my mom and my uncle had both learned some French in school and then they had tried to improve it when they were around university age, and my mom had gone to some sort of -- to a camp thing where they were only allowed to speak French and they had to sign a contract that said they'd get kicked out if they spoke any English, and --

Lauren: A contract!

Gretchen: Yeah! This is how you create this social pressure. This is not uncommon in language learning camps, actually, is that you signed yourself up for this contract.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: And my uncle instead had gone to Montreal where over half the population is bilingual.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: And at the end of their respective summers, my mom's French was quite good and my uncle's French had not improved at all, really, because he just spoke English with everybody.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Because he didn't have to do it. And so I said to myself, well, I'm moving to Montreal, I'm not going to be like my uncle -- lovely guy, but I'm not going to do this thing. I'm going to decide that the city speaks French to me, that even when people try to switch into English, I don't have to accept that. The analogy I like to use is that somebody trying to switch into English on you is like them trying to pick up the check.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: It's a very nice thing for them to do, but you don't always want to be in the situation where other people are picking up the check for you.

Lauren: Yup.

Gretchen: And once you realise that you can sometimes pick up the check, it gives you this tremendous feeling of power and altruism to be like, "I am so magnanimous and I am paying for this now!"

Lauren: So smugness is one of your secret language learning powers.

Gretchen: Yeah, be more smug to speak better, to learn language better.

Lauren: Yeah, fair enough.

Gretchen: So, you know ,if you're in a context where -- like a service-type interaction where you're in a store or restaurant or something, and someone says -- in Montreal it's very common to hear "Bonjour hi," and what they're trying to do is say, "Pick a language so I can speak to you in it."

Lauren: Right, yeah.

Gretchen: And because it's pretty much impossible to get a job in downtown Montreal if you're not bilingual in English and French.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: And so, saying, okay, like, most people, what they want in that situation is they want to be able to speak their first language. And I know this because I worked at a museum for a couple summers and I was one of the designated bilingual staff members, and when I could find a tourist who was speaking French and I could speak French to them, you could just see this relief wash over them in waves. It was beautiful. And the nice thing about, you know, particularly if I'm going to the grocery store or whatever, is you have lots of microinteractions where it's just a couple sentences. And so even if you end up in English for one of them, you can do French the next time and it's okay.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: So you have a lot of kind of micro- practice. And so I think, you know, they say that speaking a second language improves your executive functioning, or your --

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: -- you know, that kind of quick-wittedness and self-control and these kinds of things, and I think one of it is it gives you this practice in being very persistent and putting yourself in situations where you're uncomfortable and working through that, and I think that's one of the places where that benefit is really apparent.

Lauren: It's definitely given me this ability to be, like, having a very basic conversation using one half of my brain and the other half of my brain going, "Okay, what's next? What's next?" Have we got words, have we got words? What are the words? What've we got? What can I talk about next?! Um, um, um..." And I find that knowing that my brain can do those two things and I can look relatively chill while doing that has definitely helped my English public speaking. Like, I know when I lecture now, my brain is kind of doing the same thing and I'm like, well that's okay, it's just running that parallel process and it's fine, and others keep saying sentences in this really like methodical one word after the other kind of way and so, yeah, I think it does -- it helps with that level of executive functioning.

Gretchen: I think it's also taught me more about how conversations are structured. And this is something I never got in the language classroom, but how to talk around something that you don't have the word for so that the other person can supply the word for you?

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: So, like, if I want to buy a zipper or something in Montreal, I don't know the French word for zipper, but I can talk around, like, "Oh yeah, I need this thing," and point to one and they'll be like, "Oh, of course, un zipper," or whatever it is. And then I'm like, "Yes, obviously, I clearly knew this word, I just chose not to say it right now until you did, obviously."

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: And, you know, being able to use words like "this thing" or "that thing" or point to stuff or indefinite types of words, I think we spend a lot of time trying to get vocabulary lists of concrete nouns into people's heads when you can't learn all of the nouns. You need to learn how to learn nouns in context the way speakers do. You know, as a child you don't go memorise a vocabulary list of what all possible things you can put on a pizza are, you just pick them up as people are pointing to them and stuff like that.

Lauren: Yeah, definitely. I think also the difference in my language learning now is that I have moved through language and interactions and language a bit more with my linguist brain on, and so becoming more competent in the language involves more than -- like, when I was learning Polish or even Italian as a kid, it was all about learning the words and what order they go in and those kind of early language learning experiences, whereas now I pay a lot more attention to things that happen in social interactions. So how if interrupting someone is an okay thing to do or if people kind of leave a lot of silence. So in a lot of my social interactions in Nepal, people are very happy to leave long silences and I think when I was starting to learn Nepali and a couple of other languages of Nepal, I was always like, "Okay, okay, what do I say next? What do I say next? There's a silence, I have to say a thing, I have to ask a question, isn't that how it works?" And now I know the social rhythm of interactions allows for a lot more, like, "I want to sit here for a bit and then one of us can think of a thing to say, that's okay."

Gretchen: Yeah.

Lauren: Also politeness. So, like, who to be polite to and who you can be informal with. So for example, in Nepali you have different verb politeness registers for, like, a more honorific one if you're talking to someone who's more senior than you, and a much more informal one for friends, and an even more informal one that is, like, it would be so rude for me to learn it in a Nepali context that I've just never bothered to because that makes that easier. And at the start, learning who to say those things to -- and now, like, I know with some of the younger kids I know I'll occasionally use those more honorific ones if I want to be like, "Oh, I'm treating you as an adult now," like, "You're growing up," or if I want to bring someone in a bit more conspiratorially, I'll use the informal one -- and so knowing how to navigate those social features of the language, not just conjugating the verbs for those.

Gretchen: I think being able to say, like, having more tolerance for yourself on saying, if I'm going to make these mistakes, that's very interesting because this is what it tells us about my language capacity right now. Or I'm interested in what I'm doing, but I'm not as -- there's a sense of okay, well, you should just be able to acquire a language and now it's done and you've got it and you totally speak it, and that's not a thing that you end up at, but where do I have intuitions about this and where do I not have intuitions about this.

Lauren: There's a whole field of second language acquisition in linguistics that just looks at how people go about learning their second language and I remember taking that class as an undergraduate and just being really relieved to know things that we know are pretty common facts about language acquisition, like there's often a very rapid acceleration and then a plateau in learning. So moving from being an intermediate competent to an advanced speaker involves a lot more work for visible improvement.

Gretchen: Yeah, something that was very interesting for me to learn in second language acquisition classrooms was that we have this sense that, oh, you need to start learning a language as a baby because otherwise you're going to be doomed and you're always going to, you know, it's always going to be hard for you. But there are actually some domains where adults have an advantage or older speakers, older children even, have an advantage. And so children tend to be better at the phonology side, so they're going to learn the sounds, the subtle distinctions, because that's all they're being exposed to and they have that capability. But it takes a long time for kids to learn a significant amount of vocabulary or grammar. Like, if you think about a baby, right, a baby gets exposed to a language. And as many hours in a day as it's awake, for a whole year, generally, before it even says a single word. Like if you gave an adult that kind of exposure, if you had them literally only being exposed to that language and you're like, "Yeah, we don't really expect me to talk for a whole year," that's just not what our expectations are when it comes to adults. And the fact that an adult can walk out of an hour-long class and have half a dozen words that they pretty much know, even if they have forgotten half of them by next week, that's still six words that they've learned, and the baby takes like a year and a half to learn that.

Lauren: Six words up on the baby! And the other thing is that, like, I'm learning a language around having a full-time job and hobbies, whereas a child is literally doing nothing besides being fed, put to bed, hanging out listening to language, and they don't even have to speak.

Gretchen: They're not doing nothing but learning the language! You gotta learn to sit up at some point in there, too, that's pretty difficult.

Lauren: Yup.

Gretchen: But I mean, you've also got to learn a lot of stuff as a baby, like the fact that you have a mouth and that words exist and that language is possible. Like, these are things that adults don't have to learn.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: And adults have these tremendous advantages -- you don't necessarily want to be doing all of your language learning by writing stuff down because that's one of the ways that people get very dependent on a paper and not very confident about talking -- but as an adult you do have the ability to write stuff down and go study it and, you know, spend an hour of focused practice on a bunch of words and then remember them next week. And the kids don't do that kind of focus practice, already knowing how to read and write in one language makes it easier to learn it again, so there are certain advantages. So adults learn, like, vocabulary and syntax a lot quicker than babies do, even if you end up still having an accent. Also, in addition to that kind of first year where you don't expect kids to be able to do anything, there's also the later period of if you have a three-year-old who's fluent in English or whatever language, you don't expect a three-year-old to be able to do a whole lot. You don't expect them to be able to negotiate business deals or follow complex instructions or, like, write novels. There's a lot you don't expect a three-year-old or a five-year-old or even like an eight- or ten-year-old to be able to do. You don't expect ten-year-olds to know contract law.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Whereas if you're an adult and you're learning a language for business purposes, you often want to be able to go directly into a business context or directly into complex social environments, like, we don't expect kids to be particularly good diplomats in a social context where you have to keep secrets and stuff. So our expectations are a lot higher as adults.

Lauren: Good work adults, you just have a pat on the back.

Gretchen: Yeah, adults: underrated language learners.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: Even though it's difficult, and spending, like, three or four hours a week on it, which is considered a pretty good amount for a language class, is not very much at all compared to what a kid gets. I think there's a general idea that if you are really serious about being a language learner, you don't just go to class for three hours and figure you'll get it eventually. Like, people do watch movies and listen to books on tape and give themselves a whole bunch of extra exposure and stuff as well, but that's considered like a kind of high-intensity language learning thing.

Lauren: And I think it's okay if you get as far as learning how to order a coffee in Italian or you get as far as being able to make small talk with your friends in Swahili. If that's your aim, then that's great. We're not saying that you have to start a language and you have to become completely fluent in it, but knowing what social aspirations you have for the language you're learning and being aware that it's the language that exists in a culture and it has things like its own way of making jokes and being polite and having conversations definitely help you get the most out of your language learning experience.

Gretchen: It's also worth pointing out that there are different levels of resources available for language learning, like we're used to the idea that any language is going to have bilingual dictionaries or online resources or TV shows and this kind of thing in that language, and that's not something that exists for all languages either. So, you know, which languages you even can learn is something that also comes up.

Lauren: It comes back to that economic access and prestige thing that we talked about at the start and I think that's one thing to also think about when you're deciding to embark on language learning is the fact that some languages are more accessible.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on iTunes, Google Play Music, SoundCloud, or wherever you get your podcasts, and you can follow Lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr. I tweet and blog as Superlinguo.

Gretchen: And I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter and my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. To listen to bonus episodes, ask us your linguistics questions, and help keep the show ad-free and sustainable, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm, or follow the links from our website, lingthusiasm.com. Current bonus topics include hypercorrection as well as the behind-the-scenes story of doggo-speak, how to explain linguistics to employers, how to teach yourself linguistics, and swearing. And you could help us pick the next topic by becoming a patron. Can't afford a pledge? That's okay too. We also really appreciate if you can rate us on iTunes or recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone who needs a little more linguistics in their life.

Lauren: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our producer is Claire and our music is by The Triangles.

Gretchen: Stay lingthusiastic!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

[Music]

#language learning#langblr#lingblr#languages#language#linguistics#episode 10#transcript#transcripts#second language#multilingualism#tumblinguistics#podcast#lingthusiasm#adult language learning#second language acqusition#second language learning#heritage languages#child language learning#critical period#colonialism

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

april studyblr challenge

52/100 days of productivity

hello beautiful people! i hope you're safe, happy, and healthy. ✧

• today i studied language acqusition.

• read an article for my assignment & started writing it.

17. what’s currently on your to-do list?

finish all of your assignments and submit them before their deadlines.

take care, good luck & may it be easy! *.✧

#studying#studyblr#studyspo#studystudystudy#study blog#student#study motivation#studygram#studyinspo#study aesthetic#april studyblr challenge#sept-studies

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

SLA-Second Language Acqusition In this project, you will present background info

SLA-Second Language Acqusition In this project, you will present background info

SLA-Second Language Acqusition

In this project, you will present background information about one modern theory of second language acquisition, its strengths and criticisms, findings in research, and its classroom applications. This information can be presented in the form of a wiki, newsletter, narrated or annotated presentation, paper, or as a live online presentation.

You may choose one theory…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

SLA-Second Language Acqusition In this project, you will present background info

SLA-Second Language Acqusition In this project, you will present background info