Text

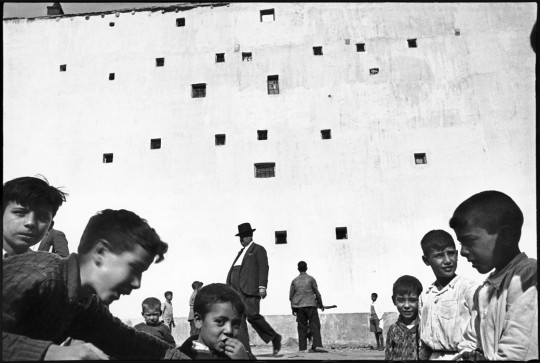

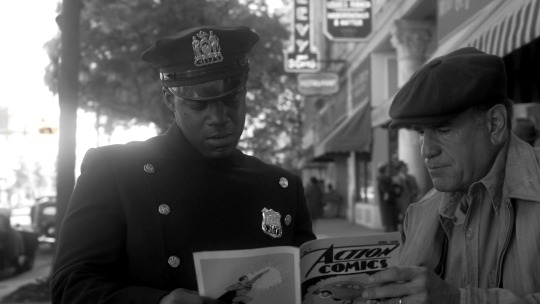

Street Photography, Beyond Coincidence

Street photography has more to offer than captured coincidences. By looking at its roots, we see its true value.

© Neal Gruer

As we all become more aware of the surreality of daily life, isolated images taken out of that context lose their impact.

— A.D. Coleman, New York Times, 22 November 1970

In many respects, spontaneously photographing strangers on the street is the simplest and most accessible way of putting a camera to use. There is no need to wrangle and cajole a subject, no need to learn about artificial lighting; no need to travel much further than a few metres from your front door. It can be done anywhere, day or night, with any equipment. Conversely, mastery of the approach is extremely difficult, given how little control the photographer has over the environment. Easy to pick up, difficult to master — street photography is an activity one can remain indefinitely interested in. Furthermore, the dynamic skills it teaches are widely applicable to other types of photography, as well as to daily life, by transforming how the photographer sees the world.

However, as the practice of street photography has expanded and modernised, it has drifted from its 20th century roots. It has become a genre rather than a description of a practice; an outcome rather than a process; a search for the shallow. By looking at how it began and seeing beyond what it has become, we rediscover how meaningful and valuable street photography can be.

One Small Snap For Man

The microbiologist uses a microscope to make small entities larger. The astronomer uses a telescope to bring distant objects closer. The photographer of people uses a camera to magnify humanity.

To such a photographer, portraiture is equivalent to the microbiologist’s petri dish: contained, specific, exclusive, finite. In turn, the spontaneous and unrehearsed photography of oblivious strangers (commonly, if inadequately, known as “street photography” — more about this definition later) equates to how an astronomer sees the night sky: vast, under-explored, overwhelming, uncertain. While portraiture is a means of interrogating the experience of a specific individual through isolated examination in a controlled environment, photographing people on the street is a means of researching people in orbit; an attempt to map the abundant, turbulent galaxy of humanity more generally. In doing so, the photographer must be simultaneously astronomer and astrologer; cartographer of the constellations, and apostle of the mythology behind them.

© Neal Gruer

This complimentary combination of observation and interpretation; objectivity and subjectivity; uncovering what is there and defining what it means, exists in some part across all forms of photography. But in the streets, there lives such a wealth of unpredictable eventuality, a photographer can cavort within the elastic space between what is seen and what is to be believed, testing his own ideas and imagination against uncooperative physical surroundings. In this grand expanse, photography becomes part of the perpetual human project of uncovering and understanding life. It contributes answers to the question, What do we do?, which may help answer, Why are we here?

Frank Explanation

The need to define certain photographers’ practices as “street” photography originated as a response to Robert Frank’s difficult-to-categorise work, The Americans (pub. 1958). It took over a decade from that point for the term to crystallise, eventually exercised in the early 1970s, as commentators and curators sought to describe what contemporary photographers were up to on public pavements. Not quite photojournalism, not quite documentation, not quite portraiture, not quite abstract, not quite realist — the method didn’t quite fit into any existing genre of photography, art or academia.

© Robert Frank

Many “street” photographers of the time disliked the term as an over-simplification of their endeavours. It spread a wide net, encompassing many photographic styles, united only by the location of the person holding the camera. Furthermore, considering “street” is rarely used as a complimentary adjective (as -walkers, -food, -dogs, -performers and -sellers can attest) the term has an inherent derisiveness to it, implying that the work is of low-quality, grubby and perhaps a little perverse. A.D Coleman deduced just that in his 1970 New York Times article, offering one of the earliest mentions of the term in print:

The pervasive phenomenon which is coming to be known as “street photography” — a somewhat random, 35mm, snapshooting approach to documentary photography which is an offshoot from (and, in part, a misinterpretation of) the methods of Cartier‐Bresson and Robert Frank — is a problematic one because while street photographers are generally more deeply into the medium than tourists, their results are frequently the same. Qualitatively better, perhaps, and usually more interesting visually; but, as we all become more aware of the surreality of daily life, isolated images taken out of that context lose their impact.

Renowned (street) photographer, Garry Winogrand, spoke specifically of his distaste for the nascent denomination stating: I think that those kind of distinctions and lists of titles like “street photographer” are so stupid. I’m a photographer, a still photographer. That’s it. Lee Friedlander’s feelings were similar — his response to anyone trying to narrowly categorise his photographs inclined towards: Just look at it. In a less absolutist vein, their contemporary Joel Meyerowitz (photographer and co-author of Bystander, the definitive history of street photography) had this to say in 2018 about categorising photographers beyond their use of a camera:

I don’t think that it is necessary in understanding photography to define one from the other [landscape, portraits, street and still lives]. I think photography is an arc that suggests you’re an artist who works with a camera and you make images about whatever interests you. So the generic term ‘photographer’ covers all. However, some people do specialize. They dig in to something, let’s say street photography, and they try to find what is it that’s so essential about photographing quotidian life on the streets of the world, what is it revealing, and what is it doing to the artist who chooses to work that way.

Born without a clear identity and facing apathy from many of its alleged parents , “street photography” was left wide open to subsequent interpretation, adaptation and appropriation. Enter the 21st century, which came along and snatched it from its cradle.

Street Photography, Capitalised

With the advent of digital technology, taking and publishing images became extremely easy. In parallel with these changes, “street” photography morphed from a small-s, small-p, deficient description of certain 20th century artists’ endeavours, to a “capitalised”, proper-noun-pseudo-genre of “Street Photography”. This contortion from description to genre is (unintentionally) well-exemplified by co-author of Bystander, Colin Westerbeck, who explains that Street Photography does not even necessitate the presence of a street:

The street as it is defined here might be a crowded boulevard or a country lane, a park in the city or a boardwalk at the beach, a lively café or a deserted hallway in a tenement, or even a subway car or the lobby of a theater. It is any public place where a photographer could take pictures of subjects who were unknown to him and, whenever possible, unconscious of his presence.

With no “street” required in Street Photography, the term begins to seem absurd. While the creative licence given to the conception of a new definition permits such vagueness, in a modern context, the street-less-ness of Street Photography has stretched that licence to the edge of expiry. Indeed, modern Street Photography can include photographs taken in any “public” place (which in turn merits further definition), with or without people, who can be known or unknown to the photographer, in staged or un-staged circumstances, with or without the participation of the subject. All that remains, as an uncompromised aspect of the root definition, is the appearance of spontaneity within the final photograph. With this precipitous reduction in clarity of meaning, the definition is now a bucket of last resort into which virtually any casual photographic act can be tossed. In its current state, A.D. Coleman’s damning assumption that it was doomed to be facile has come to fruition — a style of photography best characterised by volume, accessibility, amateurism and lack of forethought.

Now that every phone is effectively a point-and-shoot camera, everyone — to one extent or another — is a photographer. The incidental possession of an easy-to-use camera, rather than the urge to take photos, has become the starting point for most people’s entry into photography. Consequently, for the majority, this means the outcome of taking a photograph — how they want it to look in the end — forms the basis of most peoples’ photographic understanding.

Street Photography has followed suit: aesthetics have overtaken ideas; the superficial has superseded the profound; planting the flag has replaced exploration. None of these things could be said about the handful of photographers operating between 1950 and 1990 (such as Joel Meyerowitz, Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and Mary Ellen Mark) all of whom unknowingly gave rise to the definition of “Street Photography”, but paradoxically, remain poorly represented by it in return.

The Coincidence Obsession

As a result, in the digital age, Street Photography has been overrun by images of inane coincidences or people behaving oddly — “caught” on camera as they go about their lives. Popular images, with their surprise-value or high-contrast aesthetic, tend to elicit little more than a cursory reaction: a short-lived “wow”, an amused “ha”, or a “huh, would you look at that?”. After the initial smirk or frown, they typically demonstrate little else than “coincidences happen” or that people look unusual when they don’t know they’re being photographed.

Audiences at large enjoy coincidences and odd-looking people, but such things are readily visible on a day-to-day basis and are now exhaustively familiar in photographs. Again, this was pre-empted by A.D. Coleman: as we all become more aware of the surreality of daily life, isolated images taken out of that context lose their impact. Wait for long enough in a coincidence-likely spot — under a billboard or on a busy street corner — and a coincidence will occur. Wait a bit longer, and an almost identical or similarly enticing “coincidence” will occur again. Over and over, so-called coincidences will happen — each slightly different, but similar enough to make them almost all trivial. Recording these coincidences and sharing them with others does little to diminish their triviality or offer insight into the human condition — street photography’s original strength.

Indecisive Moments

This proclivity for the prosaic partly stems from a misapprehension of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “The Decisive Moment” — the first phrase which came to concisely conceptualise “street” photography and the English title of his seminal, 1952 photobook.

In its original French version, the book was titled Images à la Sauvette, which translates as “Images On the Run” (or more accurately for Bresson’s purposes, “On the Fly” or “On the Sly”). For the English version, the American publishers were keen to position the book as a technical guide to photography rather than an art book, so plucked “The Decisive Moment” from the interior text and plopped it on the cover. In a 1973 interview with Sheila Turner-Seed Bresson himself confirmed: I had nothing to do with it.

Taken out of context, this phrase inadvertently altered the orientation of Bresson’s philosophy, famously expressed in his own words at the introduction to The Decisive Moment:

To me photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.

Instead of prioritising the photographer’s irrepressible, instinctive reaction to something he sees (the simultaneous recognition…of the significance of an event), “The Decisive Moment” implies that the event itself (the precise organisation of forms) is the essential element of the image. With that, the photographer becomes more coincidental observer than active participant. The balance of the idea shifts heavily from the photographer’s internal voice finding resonance in the outer world, to recording an external, visually pleasing event. As a concept, “The Decisive Moment” has consequently become viewed as catching a coincidence with good composition — the “right place, right time” -ification of street photography. It is best exemplified by Bresson’s photograph below, of a man jumping over a puddle.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson

Printed in The Decisive Moment, it is perhaps Bresson’s most renowned, most celebrated image; said to epitomise the title. Yet when he took it, his view was obscured by wooden planks. He couldn’t see through his camera’s viewfinder and was oblivious to the man’s leap. The captured moment may have been a decisive one of sorts, but Bresson did not make the decision to record that moment. The image resulted by chance. While this does not necessarily diminish the charm of the photo itself, using it as an architype of Bresson’s philosophy misses the point.

In a letter to Life magazine editor, Wilson Hicks, just prior to publication of The Decisive Moment, Bresson clarified his position on the photographer’s interaction with world he sees (emphasis added):

I did not actually mean that one should exchange his ‘own’ world for the ‘greater world outside’. I believe that through living, one discovers oneself simultaneously with one’s discovery of the world outside; a proper relation has to be established, there is a reciprocal reaction between both these worlds which in the long run form only one. It would be a most dangerous over-simplification to stress the importance of one at the cost of the other in this constant dialogue.

Modern Street Photography has fallen into this trap, presenting an over-simplified view of the world outside at the cost of the photographer’s own world. This absolves the photographer from finding meaning within the moment, beyond its sheer existence. It misses the need for the event to be eloquent, as well as for the photographer to feel something substantial in response to it. It is that feeling — the photographer’s deep, personal sense of stimulation from what is happening before him — which gives a street photograph its value. The thing happening is not, in itself, significant. Without the photographer’s feeling, the moment, in itself, is indecisive.

Repetitive Strain

The website and Instagram feed Street Repeat usefully proves the point. Arising from a fascination about how different Street Photographers take similar photographs, the project creates trios of thematically similar contemporary images:

Instagram, @streetrepeat

While not the intention of Street Repeat, the images it presents reinforce how trite modern Street Photography can be. Contrast this with the work originally described as street photography. It was full of intrigue, because the ideology and individuality of the photographer — the “feeling” behind the images — was self-evident. Whereas modern Street Photography is primarily defined by singular, out-of-context photographs that capture a split-second coincidence with some modest aesthetic value, original street photography had philosophies behind it; deeper expressions of life that gave the complex images (and their creators) enduring relevance.

© Joel Meyerowitz

© Henri Cartier-Bresson

© Lee Friedlander

Before it was so-called, street photography was primarily the task of revealing what a photographer thought, not what he saw. Each photograph was a reaction, not simply a record. Amassed over time, single images were built into descriptive collections, effervescing with authorship. To paraphrase Meyerowitz, having a camera and using it to take pictures was incidental to the artistic intentions of its holder. The camera only happened to be the person’s chosen method of revealing what he already thought — a technical means of achieving a well-considered end. In contrast, modern Street Photography is the end in itself. It is the acquisition of a “type” of photograph — the source of the idea as well as the outcome, objectively showing little more than what happened front of a camera at a certain time and place.

Such is its ubiquity, we are probably stuck with the modern usage of “Street Photography”, but those who take “meaningful photographs of unrehearsed events, compelled by spontaneous emotional responses” deserve to have their work more loosely defined. Such photographers may perform with a “street” mentality — raw, imprecise, and makeshift — but the results can be deeply revealing. At their best, such people are not merely “photographers”, as Winogrand hoped, but in fact philosophers, poets, ethnologists, sociologists, anthropologists, authors and historians; defined not by a genre, but by the insightful ideas their photographs intimate. Beyond coincidence, and even beyond photography — that is where the greatest value lies in photographs from the street.

To see more of my work, including plenty from streets across the world that hopefully extend beyond coincidence and occasionally beyond photography visit nealgruerphotography.com.

0 notes

Text

The Sensational Nothingness of Weight Loss

The cumbersome truth behind shedding unwanted kilos.

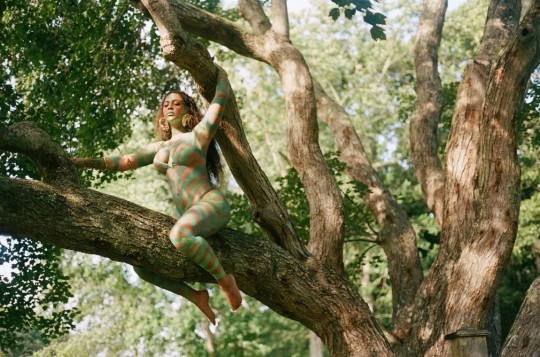

© Neal Gruer

In early August, slumped on the sofa like a sonsie haggis stuffed into a sports sock, I finally accepted it. My trousers were too tight. During spring lockdown, while Covid case numbers happily decreased, the numbers on my bathroom scale had been surging in the opposite direction.

Like many others, in pre-lockdown anticipation of being stuck at home, I swiftly purchased a sizable quantity of flour. I rarely buy flour, but it felt like a safety net — if supermarkets ran out of food, with just a little water and a sprinkle of salt, I could still concoct some basic sustenance. Of course, aside from toilet paper, pasta, hand sanitiser and (ironically) flour, the supermarket industrial complex persevered, and the shelves remained healthily stocked. With that, I could have left my flour in peace to become a contentedly superfluous powder; patiently waiting at the back of the cupboard for some kind of cake emergency. Instead, it coerced me.

I set about mastering the dark art of baking chocolate chip cookies. With only me and my partner available to consume the melty, chewy, crunchy discs of delectable deliciousness, the baking brought a lot of eating, justified by the “need” to make another batch… you know… for practice.

By batch three, my waist was beginning to suggest I’d had enough practice, but I ploughed on — surely it was worth doing another batch of the exact same recipe to see if, you know, maybe… umm… the texture could be a little better? Nope — by batch five the texture was the same (magical, uplifting, come to papa), but my gut was not.

Thirty Plus

With a well-honed sense of denial, I could claim “the coronavirus made me do it”; that the 100 cookies the pandemic imposed on me were entirely responsible for my weight gain. But who am I kidding? Even with broadly eating healthily and exercising regularly since turning 30, it has taken a while to accept that my body, in its fourth decade, does not function as efficiently as the bouncy little spandex and rubber one I was born with. Like a 1985 Volvo, despite keeping the tyres pumped and the paintwork shiny, without regular servicing under the hood, bits quickly begin to groan and fall off. The suspension gets rusty, the battery loses charge and yes, the drive belt gets a bit flabby.

Uh oh, July 2020.

Weight gain is gradual, a kilo here, a kilo there. Every year, the benchmark changes — “well, this is the weight I am now”. For a while, the incremental increase is minimal enough to tolerate, but eventually a threshold is crossed and an awakening is triggered. In my case, it was a sudden influx of fresh-baked, chocolatey biscuits and the discomforting pinch of taut fabric.

For that realisation, I have my previous self to thank. As a lither, slighter, younger man, I bought clothes ill-suited for growing into. Quite the opposite — I bought togs on the edge of smallness, giving my elder self a message: “When these don’t fit, you’ll have two options: buy a whole new wardrobe or trim some timber”. Being half-Aberdonian and therefore stereotypically unlikely to spring for a costly, multi-season catwalk of replacement outfits, the method was destined to work. Particularly since I was still comfortable with how I looked and felt, I needed a different motivation. When faced with the prospect of shedding fat or shelling out, shed effortlessly beat shell.

So, days before my 35th birthday, I embarked on my maiden attempt to lose a sizeable amount of weight. From a peak of around 84kg (13.2 stone), the aim was to get down to 72kg (11.3 stone); losing around 15% of my mass. Incidentally, that’s 12 bags of flour, enough to make 1200 cookies.

I had very little concept of what those numbers meant in practice. How long would it take? How challenging would it be? Did I (quite literally) have the stomach to get there? I at least hoped that by the time my Dad was carving the turkey-emoji with his iPhone over Zoom, Digital Christmas would not be the only thing I was celebrating. But just 11 weeks later, here I sit — slightly shocked — weighing a little under 70kg (11 stone), lighter than I was 10 years ago. Now, my Aberdonian half is concerned that my winter wardrobe might actually be a little too baggy.

Building the Shed

This isn’t exactly a “how-to”, but if you’re curious, I’ll more fully lay out the practices I used to get there at the end of this article. In short, I took measures to apply the only completely true (but annoyingly facetious) advice I have ever heard about losing weight: “consume fewer calories than you burn”. Work out how much your body needs to function then eat sufficiently less than that until your trousers stop trying to self-detonate.

In this respect, losing weight was conceptually straightforward, if practically a little onerous. Between kitchen scales and the help of an app, I set about measuring every single calorie I consumed, maintaining a low daily target to keep me in check. Besides cutting out some obviously calorific things (bye bye beer, farewell fromage), my diet remained largely the same, only smaller. With the pandemic, socialising and eating out has been minimal, helping enormously to remove temptation and uncertainty about what I was eating. And since I work from home, I had a lot of control over the food around me.

Eating less than I needed worked as advertised. Now, it’s hard to imagine going back to recklessly and gainfully eating unquantifiable calories.

Lighter, September 2020.

The Cumbersome Truth

Having said that, as the weeks rumbled on like an empty stomach, I came to realise why, on a metaphysical level, losing weight and keeping it off is extremely challenging. Why there is a huge industry built around it. Why there are thousands of gadgets for it. Why it fills our social media feeds. Why you’re reading this article about it. It’s not the food, or the habits, or change of lifestyle. It’s the unspoken requirement to combat sensational nothingness. Losing weight is difficult because there is absolutely no tangible sensation that comes from doing it. While the eventual results can be immensely satisfying, the effortful process itself is almost entirely unrewarding.

Of course, good feelings arise once your clothes fit better, you prefer how you look, or you can move around more easily, but these are all consequences of already having lost weight. In the process of losing, even though your body is rabidly consuming bags and bags worth of cookies from the inside, it gives you absolutely no sensation of what it is doing. We talk about burning fat, but we cannot feel the heat. We talk about metabolisms speeding up, but there is no sense of acceleration. We talk about dropping pounds, but cannot see the lumps falling off. We reduce what we eat for long periods in a blind belief that the body will react and eventually show the results, but we get no direct or immediate physical satisfaction from the body’s process of shrinking itself.

Drink more water! Fast intermittently! Cut out carbs! Use smaller plates! Eat spicy foods! Run! Lift weights! Sleep more! Eat less fat! Eat more protein! Eat whatever you want! Chew more slowly! Only eat cabbage!

So goes the advice on “how” to lose weight, but all these tactics fail to acknowledge the cumbersome truth — losing weight is a process of endurance in the face of nothingness. No matter how many gallons of water you guzzle; farty buckets of cabbage you swallow; magnificent, ambrosial, chocolatey cookies you avoid; or slabs of iron you lift, you have to accept that losing weight has no sensation and zero, real-time gratification.

No amount of tools can replace what it would be like to feel the loss of weight as it’s happening; to be able to know what you are doing is having a meaningful effect. Imagine getting a spurt of endorphins each time your body permanently deletes 200 grams from your squishy hard drive. Weight loss would be a breeze. In that respect, it could compete with the giddy feeling of eating a delicious, sweet, fresh-baked — let’s say, for argument’s sake — cookie. Even before you open your mouth, the feelings spark and fly from the smell. How can silent abstinence from the cookie compete with the marvellous sensation of guzzling it? Alternatively, compare it to exercise. As you run, all manner of glands and vessels erupt with liquids and chemicals. Your muscles tighten and tire, or flex and endure. You can feel it all over. Perhaps this is why, despite exercise having only a minimal benefit for weight loss (i.e. a 5km run only burns 1.5 cookies), doing it as part of a weight loss programme might be helpful, since the subsequent tiredness and discomfort at least creates the illusory feeling that you are actively “burning” the weight away.

Fake the Feeling

To make weight loss sustainable, it is imperative to create this kind of artificial feeling — a blinking light on a fitness tracker, extra money in the bank, the satisfaction of a widening gap between tummy and trousers. It’s an intellectual activity rather than a physical one. As the process goes on, the good feeling comes from decreasing numbers on your scale or the reappearance of your waist rather than your body’s natural response to being starved of fodder. It’s strange — feeling nothing, yet knowing that, if you want to see results, you need the nothingness to persist.

Which brings us to the corresponding challenge — time. Weight loss is a thoroughly time-reliant activity. In order for your body to achieve the organic change you’re demanding, it needs time. Your body knows nothing about calories, kilos or clocks. All it knows is that it has to keep going — the Volvo keeps sputtering on, with less fuel in the tank. One day to the next, your body is indifferent for your need to see progress. Cutting 500 calories a day might feel like something huge for you, but your body operates on longer time frames, with bigger equations. It needs to experience a drop of thousands of calories per week, or tens of thousands a month before it shows its hand. Some weeks it will, others it won’t.

To combat sensational nothingness and this viscosity of time, losing weight requires two, hard to access characteristics — patience and delayed gratification, both things we are born without. Our recently digitised, consumerist culture of speed and immediacy strives so hard to keep us from gaining them — especially when it comes to food. It’s a significant test of resolve, or alternatively, indifference. To get through it, you either have to become either a pious believer, dogmatically following the 54 Cosmo Commandments of weight loss, using every trick and tool to reach nirvana; or an indifferent agnostic, setting new behaviours and blindly going following them, occasionally acknowledging that your body has changed. Either way, while undergoing the process, it is unflinchingly thankless and strangely dissatisfying.

Yet, here I am, 14kg lighter and, I suppose, happy not to be 14kg heavier. In honesty it’s still not the number on the scale that pleases me, nor that I look slimmer. Mainly, I am happy because my clothes are no longer under such duress, and as a consequence, my money remains in my bank account, instead of with Zara.

So, if you’re attempting to lighten the lockdown lumber, find your artificial feeling, eat fewer calories than your body needs, trust the process and accept the nothingness. Eventually, you’ll get the rewards.

(And sorry if you are now insatiably desirous of cookies.)

...

What I did, If You’re Interested

Knowing the recommended calorie intake for men is 2500 per day (which, in all honesty, seems high if you mostly sit at a desk), I plucked an arbitrarily round, low-seeming number out of the air (1500), and plugged it into Under Armour’s MyFitnessPal app. It’s a bit clunky but very functional, featuring a huge database of pre-loaded ingredients; and the ability to build the calorie content of home-made recipes, or quickly scan barcodes of pre-packaged products and download accurate nutritional information.

I then recorded every single liquid and solid that passed my lips, even water. At the beginning, this required me to be extremely strict on myself. But over time, it got easier and easier, partly through habit, and partly because the process led me to eat fewer and fewer rogue snacks that are easy to forget about.

The type of meals I ate stayed largely the same, although portion size at each sitting decreased significantly. For example, it was fine to have a plate of unctuous, cheesy pasta, so long as the portion only amounted to 550 calories. In this respect, my little kitchen scale became a big part of everyday life. Used in conjunction with the app, I was able to calculate the calories of every meal before cooking it. It is surprising how quickly a meal can go from a reasonable 500 calories to a target busting 800. In general, through habits gained, Monday to Thursday ended up being between 1000 and 1200 calories per day, with Friday to Sunday between 1200 and 1600.

For this, the lockdown-imposed habit of visiting the supermarket just once a week was extremely helpful. Having to plan a week’s eating in advance takes the spontaneity out of deciding what to eat, therefore avoiding sudden hunger, ill-advised snacks or reaching for the most convenient option. Also beneficial was the lack of opportunity to eat out, sit in coffee shops or socialise in general. Controlling and knowing how many calories you are consuming is incomparably easier when nearly everything you put in your mouth is done at home, you prepare everything you eat yourself, and you know every constituent part of your meal.

The major exception to this was Friday nights, when we would make a hefty take-away order of burgers and fries (and still do). Having a single, pre-ordained, weekly splurge to look forward to — I guess a so-called “cheat day” — made the other six, lighter days more bearable. Importantly, we never saw it as cheating, just part of an overall, calorie-managed week of eating.

Besides that, I introduced a bunch of arbitrary rules: zero alcohol Monday to Wednesday, and minimal booze on the weekend (2–3 units a day). Beer was never consumed at home. Instead, spirits with light mixers, neat whisky or the occasional small glass of wine. Otherwise, water, tea or black coffee. No crisps or bars of chocolate. No desserts Monday to Thursday, but a cookie (or equivalent) permitted on weekends (typically half a cookie with 20g of vanilla ice-cream — an immensely satisfying 160 calories). There were exceptions to these rules — two birthdays to celebrate, infrequent visits to the pub where a beer (or even two!) were had, but for the most part, the rules simply transformed into behaviours — no longer imposed but habitually followed.

I also started running 5km three to five times a week. However, my rate of weight loss seemed completely unaffected when I stopped running for a month, after picking up a small injury. The exercise felt good, and I continue to do it, but the 350 or so calories burnt on each run appear to have little impact on my weight.

Perhaps most importantly, I did all this under pandemic conditions along with my partner, who is virtually my only social companion these days. Having also partaken of the cookie extravaganza, she was equally keen to lose weight. Since we both integrated the weight loss process into our lives, it became extremely normal. I suspect it would have been harder to do alone or with a dissenting partner; or in a non-pandemic environment, with open restaurants and bars; or when nights out and socialising are back on the menu. Done as a pair, it was an enjoyable project: I could congratulate her when the scales reported progress and vice versa. This was especially beneficial when one of us was experiencing an apparent, frustrating stall in progress — it proved that the process was still working, at least for one of us. She lost over 8kg (1 ¼ stone) in the same period.

We have both long since reached our “target” weights, and our bodies have naturally responded by needing fewer calories to function. Even so, we have maintained the same approach to food. We continue to lose small amounts of weight loss but it has slowed considerably from around a kilo a week to a few hundred grams. We both have a (proximate) number in mind, when we will actively stop losing any more weight. Then, we’ll try to find a new balance, where calorie intake closely matches calories burned and our weights stabilise.

Regardless, we will persist with our new eating habits, which have become comfortable to live with. It now seems ludicrous that we ate and drank for so long without any real understanding of how many calories we needed or consumed. Measuring and recording everything has given us a much better sense of what is likely to be in any given meal; training us in portion sizes and kilojoule contents. When we go back to eating without measuring, we will be better at mentally estimating and hopefully, better at avoiding “cookie creep”. All in all, for the sake of a few months of nothingness, the results have been significant and hopefully long-lasting.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Embracing Failure in Photography

In every photograph taken, there exists profound potential.

Istanbul © Neal Gruer

We will all end in failure, but that’s not the most important thing. What really matters is how we fail and what we gain in the process.

- Costica Bradatan, In Praise of Failure

An artist’s life is a never-ending, unresolvable, inconclusive search for the perfect expression of an internal sensation as it relates to the wider world. In this endeavour, most are lucky if, a handful of times in their entire lives, they stumble upon something merely approaching “decent”. Consequently, rather than being preoccupied with creating, the artist spends vast resources interrogating themselves from within, and observing the world at large, carrying the faint but persistent hope of working out who they are, what they think, and what is worth expressing. The goal is to produce an artwork that contains at least a slither of that intended expression, and to hope beyond hope for a slither of that slither to contain some understandable meaning. In this regard, art is built from a catalogue of failures, falling one onto another, eventually making a stack tall enough for something to be plucked from the elusive top shelf of meaningful expression.

In photography — particularly the improvised forms of street and field photography — the arduousness of this process is clear. Not only do you need to take a ton of photos in order to find something worthwhile, but you need to spend many exhausting, sole-wearing, soul-wearing hours walking around on high alert, searching. Alex Webb goes as far as to put a number on it, maintaining that “99.9% of street photography is about failure”. Even he, one of the most renowned practitioners in the history of the field, aims for just 1/1000 photographs to be a success, of which only a small percentage will become widely celebrated. If, at best, just 0.1% of an artist’s effort is successful, how is the overwhelming “failure” to be understood?

In life generally, we tend to misplace “failure”. We look at the outcomes of our activity and judge it against arbitrary, extraneous benchmarks. In photography, failure is typically positioned in one of three places: the appearance of the final image; the technique used to take the picture; or “missing the shot” in the first place. In truth, none of these are where the real failure lies. Arguably none are even failures. Instead, the only failure in photography is a failure to see; to purposefully engage. Why? Because regardless of whether you end up with something materially valuable, the contrails of purposeful engagement will linger with you, no matter what.

Failure Fanatic

Personally, by choosing to become a field photographer with manual, mechanical, half-century old, analogue cameras, I have deliriously maximised my relationship with failure. I am a flop aficionado; a bungle believer; a disappointment devotee; a washout worshiper. Compared to digital photography, which is increasingly moving towards a zero percent failure rate, manual film photography has the potential for failure at every turn: leaving the lens cap on; unknowingly using expired film; irreparable over- or under- exposure; inaccurate focus; mechanical failure; failing to wind the film forward; moving too slowly to catch the moment; running out of film before the moment arrives; light leaks from accidentally opening the back of the camera (FFS!!); light leaks from deterioration of the camera’s sealant; film exposed to x-rays in airport security; film lost in the post on its way to the developer; film incorrectly or poorly developed; or maniacally smashing the camera against a wall out of pure frustration at all of the above.

Anyone shooting manually on film must accept, from the outset, that no matter how well-intentioned, experienced, capable or careful, at some point, one of these failures is inevitable. Failure is deeply embedded into the process and only so much within your control.

Beyond the practical failings of taking pictures, in metaphysical terms it is arguable that, rather than only 99.9% of photographs failing, the failure rate is 100%. Whether on film or digital, no photograph will ever fully replicate the internal stimulation that prompted you to take the photo. First, given the limitations of biology, converting a thought into an act can never be done with complete accuracy. It can be close (the exploits of Simone Biles and Nadia Comaneci are testament to that), but there will always be a minute or massive degree of approximation between what you intended to do and what you did. Second, if you do manage to catch a scene as close as physically possible to what you had envisaged, in every photograph there remains an insurmountable structural failure: the inability to convey the entirety of a three-dimensional, five-sensual human experience into a comprehensive, two-dimensional, visual testimony.

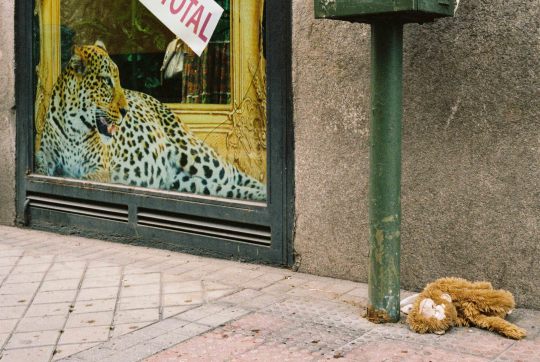

Madrid © Neal Gruer

Seeking Success

If indeed the physical act of photographing and the photograph itself are cursed to fail by their very nature, then where in the photographic process can success be found?

Ultimately, each photographer must find success within themselves, in the internal exploit of seeing, and seeing well — the deliberate operation of visual, intellectual conception; grey matter moulding grey clay of sight and emotion into an exhilarating, vibrant sculpture of idea and object. If your body fails to compel the camera into action, or the camera fails to record your bodily response, or if everything goes as well as possible, but the resulting image is lost or destroyed; provided you succeed in the act of instantaneous conception, you will be forever changed, minutely or massively. If you screw it up, lose it, miss it, destroy it: you still saw it; conceived it; “took” it. Even without a camera to hand, the exercise of seeing well offers boundless thrills, but the camera acts as an amplifier, pumping up the volume on the jazzy rhythm of human existence. Fundamentally, it’s about being a photographer rather than taking photographs.

Ironically, this mentality is the furtive ground on which taking meaningful photographs is sown. What you have seen becomes part of who you are, and will forever exist as one of the many grains that fills the beach of a future photograph; a future artwork; a future profound, non-photographic interaction with the world.

Under this process, there is no such thing as missing a shot — there are only shots gained. I shall furnish you with an example.

Photographing Phantoms

As a field photographer, I roam around looking for stirring, naturally occurring scenes to take pictures of. In March 2017, for four days, I was doing this in Bucharest, Romania.

Having nearly finished a roll of film, I took my afternoon break. Inside a coffee shop, a server in boy-fit jeans, a navy roll neck and oversized, wire-rimmed glasses gleefully introduced herself to me: “Cristina”. With hair bundled anarchically into a blonde, cotton candy nest, she took my order and asked me about my camera. Surprised by her enquiry, I fumbled my way through an explanation, vainly attempting to seem simultaneously aloof and interesting.

Immediately, I was taken by her manner and appearance. With one frame remaining before changing the roll, I resolved to ask for her photograph. But between her busyness and my sheepishness, I failed to catch her eye. Despite sipping my flat white as slowly as I could, the opportunity never arose, and with the encroaching dusk hastening my need to get back to work, I relented, clumsily asking one of Cristina’s colleagues to play subject. I took the picture and wound the roll onward, expecting to hear a click. To my surprise, despite showing “37” on the counter (typically the maximum number of frames on a 35mm roll of film), there was no resistance under the winder. I still had one frame left.

Suddenly, positioned by the till under a theatrical spotlight, there stood Cristina. I approached her. Besides paying for my coffee, I paid her a gentle compliment and quietly asked for her picture. She bashfully agreed. I shot and wound to 38. This time, click! In a moment of rom-com reproduction, she asked for my details in order to see my work. Like a struggling salesman at a vacuum cleaner conference, I fingered through my wallet and formally delivered her my card. We exchanged smiles, and I left; flustered but buoyant.

The next evening, I returned to the coffee shop for an evening cocktail event. Cristina was there. We spoke, expansively. After the event, we went to a bar and continued speaking. Then to another, and another; diving deep into the night before floating towards the shallows of early morning and departing each other’s company, possibly forever.

But within three months I had moved to Bucharest. Within four, we were living together. Three and a half years later, here we still are.

Not knowing how this would all turn out, photographically-speaking, you might say two things are important — first that taking Cristina’s photograph furthered the nascent channel of communication between us; and second, that I will always have that precious photograph from the first time we met.

On the latter point, you would be wrong. As it turns out, the last frame on my roll of film was a phantom. There was no film left, no picture to develop. I took her picture but have no picture.

However, I do have her.

Cristina, March 2017

Art Imitating Life

As this (entirely true, yet implausibly romantic) example demonstrates, taking the photo was more important than having the photo. Whereas it would generally be perceived that I failed in taking Cristina’s photo, in truth it was an enormous success. It opened me up and my life was irrevocably changed.

Yes, to have the 3:2 image from that moment would be amusing — one can imagine it being wheeled out over the decades at any major celebration of our partnership; the first, rectangular page of an amorous, amorphous fairy-tale. We would intermittently return to it, pouring over Cristina’s expression, projecting thoughts into her then-head; arbitrarily amending those thoughts to suit our wavering memories of the moment. But self-evidently, the physical image has become entirely irrelevant.

Success was achieved the moment I meaningfully, deliberately, and honestly engaged with the world through my camera— here, in the delightful, atomic shape of Cristina. After doing so, the ability to subsequently show anyone what that moment looked like became largely frivolous. Admittedly, the extraneous consequences of this engagement were extreme — it’s highly unlikely for the love of your life to emerge every time you take a photo (if nothing else, I’m 99.9% certain Cristina would now prefer I ensure this is not the case). In fact, most of the time, I am photographing people who never know I have taken their photo, who I don’t directly speak to. But even if I never saw Cristina after that moment, or had taken her photo without her knowing, I would still have aspired to have been meaningfully transformed by the act of releasing the shutter.

Cristina, June 2017 © Neal Gruer

Finding success in seeing rather than taking equates to a certain philosophical view of life in general, where success lies in being rather than doing. As mortal creatures (at least until Elon Musk devises an alternative), human life is characterised by failure — eventually our bodies flounder, and we cease to exist. Yet arguably, it is the inevitability of this failure which drives us to love, explore, create and accomplish. Being a photographer can help put this philosophy into practice. If you get a few good pictures along the way, all the better.

See more of Neal’s photographic work at nealgruerphotography.com.

0 notes

Text

Drawing Blood: A Monumental Conundrum

Bucharest’s Memorial of Rebirth and the enduring tension between vandalism and art.

Memorialul Renaşterii, March 2017 © Neal Gruer

Vandalistic behaviour is a feature of malfunctioning, inegalitarian communication channels. It constitutes the speech of the dumb, the powerless and of minorities. There can be no doubt that it is a striking form of interrogation — and that it calls for an appropriate response.

- J. Sélosse, Vandalism: Speech Acts

An egregious act of vandalism was recently committed against one of Bucharest’s most recognisable monuments. Not by a disgruntled teenager, a political protestor, or a subversive artist; but by the State. Locals now pass through Piața Revoluției aghast, disbelieving their eyes as they come across a scene forever changed. Yes, they are shocked to find that City Hall has cleaned and refurbished Memorialul Renaşterii; removing all the graffiti and making it look as good as new.

But wait… how could that be vandalism?

With monuments around the world being criticised, clobbered, coloured and culled for their heritage, questions of “vandalism” are especially pertinent. It is important to understand what we should prize and what should meet its demise. Is vandalism ever legitimate as art or protest? Is it possible for the State to act as vandals? And can vandalism, itself, be vandalised?

The story of Bucharest’s Memorialul Renaşterii (The Memorial of Rebirth) provides a vivid example of just how multi-faceted these questions can become.

Memorialul Renaşterii

Unveiled in 2005, Memorialul Renaşterii commemorates those who died during the 1989 overthrow of Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu. Standing 25 metres tall on Piața Revoluției (Revolution Square), its main feature is a narrow, white, marble “Pyramid of Success” (Piramida Izbânzii); piercing through a large, embellished, bronze ellipsoid. At its base, a group of abstract figures face Zidul Amintirii (The Wall of Remembrance), which memorialises 1,058 names in brass. The wall is split into two parts by Calea Biruinței (The Road to Victory) — a path of oak logs leading towards the monument. Notably, the entire piece is positioned directly in front of the imposing former headquarters of the Romanian Communist Party.

Memorialul Renaşterii, October 2020 © Neal Gruer

Monuments of this sort have a controversial predisposition — cost, design, placement, politics and corruption are all potential pitfalls. Memorialul Renaşterii was no different, tripping into all of them.

The public cost of 56 billion old lei (equivalent to around €2.1 million today) was considered expensive, particularly while Romania was facing economic upheaval (in 2005, Romania’s currency underwent a massive revaluation exercise, with 10,000 lei becoming 1 leu). The design was widely derided: too abstract; overly complicated; out of place; failing to do justice to those it was supposed to represent; or simply, ugly. Placed alongside numerous existing statues of various styles, it added to a space already overpopulated with incongruous structures, opening another area of grievance.

Furthermore, Romanians were instinctively concerned about the likelihood for pernicious politicisation of the monument, particularly given their tumultuous history, with 11 heads of government over the previous 16, post-Communist years. As for corruption, Romanian politics have been rife with it, so it is unsurprising that many sceptical eyebrows were raised when Alexandru Ghilduş, a man known primarily for product design, was selected to lead the lucrative project. How else could an applied artist — known primarily for designing optical equipment — get the job ahead of 14 other artists, sculptors and architects…? In spite of the apparently open competition for the project, speculation subsists that the selection committee was overruled, with Ghilduş unilaterally chosen by the outgoing, third-term president, Ion Iliescu, who allegedly determined: “This monument is mine and I am the one who chooses it!”

Iliescu himself is the complex, cumbersome hinge of this creaky tale — hero or villain, depending on your preferred version of history. Either way, it is undoubtedly his monument. A former member of the Communist regime who became Romania’s first democratically elected head of state, he was the political face of the ’89 Revolution. Now aged 90, he is currently facing a drawn-out, Covid-delayed trial for crimes against humanity allegedly committed during his initial rise to power. Rather than leading a popular revolt, he stands accused of instigating a conspiratorial coup d’etat through a disruptive campaign of disinformation and media manipulation. His actions are said to have spread confusion and fear between the police, military, and general population in the days after Ceaușescu’s removal, with over 800 people killed amidst the chaos.

Their names now adorn Memorialul Renaşterii.

Regardless of whether objections to the monument were untrue, subjective, unjustified, or purely speculative, the public mood around the project was troubled from the outset. It immediately gained notoriety through an extensive list of inventively derogatory nicknames, many of which are still used to this day. Among them: The Speared Potato, The Failed Circumcision, The Penetration Monument, Brain on a Stick, Olive on a Toothpick, Walnut on a Spike, Skewered Meatloaf, Potato of the Revolution, The Tube and the Testicle, Shit on a Stick, The 56 billion Thorn, and Kitsch with a Diploma.

Naturally, by 2006 it the monument had its first taste of vandalism, embellished with the stencilled face of anarchist character “V” from V for Vendetta. However, after being swiftly cleaned, it enjoyed a period of untouched tranquillity, left alone to prod aimlessly at the sky…

Blood from a Stone

…Until March 2012, when an anonymous act of adventurous vandalism emphatically changed its appearance for the best part of a decade. Under cover of darkness, a modest amount of red paint somehow found its way onto the underside of the bronze globule, causing the monument to “bleed”. Positioned with remarkable accuracy around 20 metres high, how it got there is anyone’s guess, but that it remained there for over 8 years raises just as many questions.

In surviving until this year’s refurbishment, the bloody injury to the marble spire became an essential part of the monument, imbuing it with profundity and animation that was previously lacking. More than a superficial protest against the monument itself, it revealed the invisible subtexts of Romanian society: state inaction at rectifying ills; decades of oppression before democracy; and the tragic violence and corruption after it was obtained. Of course, vigilante remodelling of state monuments isn’t new — in Bulgaria, the short-lived transformation of a Soviet war memorial into a American pastiche provides an amusing illustration. But the simplicity, specificity, solemnity and longevity of that dash of red paint made Bucharest’s effort exceptional.

Monument to the Soviet Army (Паметник на Съветската армия), Sophia, Bulgaria, 2011

On my first visit to Bucharest in 2017, I was stunned by the monument, purely because of the fascinating red accent dripping from its side. It never crossed my mind that it was anything but part of the design — an extremely bold, powerful symbol of lives lost to violence. Upon later discovering it was an act of vandalism, I was even more taken by it — a subtle but meaningful act of illicit interaction with a public artwork, elevating the original piece. Despite not knowing the intentions of the vandal, its effect — deliberate or otherwise — was profound.

And now, it’s gone. Coagulated by the state, only a barely perceptible outline remains, a faded scar of dissent. The unstoppable bleeding not only gave a dose of humanity to a cold, angular structure, it emphasised that all was not what it seemed; that something was amiss; that there was more to the story than the official version — a truth so acute it drew blood from metal and stone. This gratifying graffiti, this pained paint, for so long a mark of exclamation, has finally been deleted.

Memorialul Renaşterii, October 2020 © Neal Gruer

In truth, the monument had fallen into such disrepair that by 2020, an entire renovation was long overdue. It would have required a brave and limber justification to leave the most prominent mark of graffiti while removing the “unartistic” scribbles from the Wall of Remembrance, clearing overgrown grass from the Road to Victory and repairing marble tiles damaged by skateboarders. Cleaning the whole thing made perfect, logical sense.

2018 © Pro TV

It just seems that by then, the “whole thing” had come to include that audacious, elegant, dramatic dribble of paint. Just as with Glasgow’s famous Duke of Wellington statue, which would be naked without the perpetual, vandalistic traffic cone on its head, Memorialul Renaşterii has been unthinkably unclothed. Vandalism or not, by wiping away the paint, the monument lost more than it gained.

In lamenting its disappearance, I wonder what my feelings imply. Am I romanticising a wanton criminal act, which desecrated the site and demeaned the work of a celebrated designer? Or did the paint’s erasure undo a legitimate piece of public art and unravel an important, open-air conversation between a state and its people? Where lay the vandalism — in the monument, the paint or the act of cleaning?

Vandalism Wasn’t Built in a Day

Humans have been vandalising since time immemorial, but the term stems back to the unruly Germanic Vandal tribe, who successfully captured Rome for a fortnight in 455 CE. While pillaging the city they destroyed works of art, monuments, statues, and other relics. The Romans, in their cultural enlightenment, were so appalled, the Vandals’ barbaric reputation stuck. Even so, the term Vandalisme wasn’t coined until 1794, when Bishop Grégoire wrote of his upset at the damage to ancient inscriptions after the French Revolution. The Parisien later stated in his memoirs that, “Je créai le mot pour tuer la chose” (I created the word to kill the thing). Evidently, he failed on the latter count — both the word and “the thing” have stubbornly survived.

These days, while vandalism has broadly come to mean anti-social destruction of someone else’s property, its definition remains nebulous; varying between countries, legal systems, cultures, and class structures. No matter where you are, it is almost always considered to be deviant, problematic behaviour. Understandably so — there are obvious costs and consequences to damaging things, particularly in such a visible, public manner. Minor destructive acts can make a place less pleasant to live, amenities less functional, and potentially cause a strain on mental health. Besides that, particularly when done at scale, the economic implications can be huge. It leads some to suggest that vandalism is always detrimental and should never be tolerated, arguably creating an environment for more serious crimes to occur.

Nevertheless, in the mid-20th century, Stanley Cohen and other sociologists began to develop a more nuanced understanding of vandalism. Beside identifying numerous forms of vandalism (including acquisitive, vindictive, tactical, playful, malicious, and ideological), Cohen saw beyond the common conception that it was purely childish, nihilistic behaviour. He acknowledged that a vandal’s motivations were complex and varied, and in certain circumstances, not necessarily deviant:

…in the case of vandalism, the construction of a ‘pure’ or ‘objective’ behavioural definition is only the beginning of the story. It is quite evident that: (i) not all such forms of rule breaking are regarded as deviant, problematic, criminal or even are called vandalism; (ii) not all the rules which forbid illegal property destruction are enforced; (iii) not all the rule breakers find themselves labelled and processed as deviant.

The problem, then, is to explain the conditions under which a society transforms the raw material of rule breaking into fully identified deviance.

- S. Cohen, Sociological Approaches to Vandalism

Blurred Lines

Motivations aside, as an act of vandalism, graffiti — the category into which Bucharest’s splash of red paint would fall — is probably the most prevalent. Practiced since cavemen marked walls with rudimentary shapes, the invention of aerosol spray paint in 1949 made drawing on urban spaces a modern pastime. With such a convenient tool to hand, from the 1960s onwards, graffiti caught the creative imagination. Alongside the burgeoning, anti-establishment musical movements of punk and hip-hop, ripe blank walls — seen as symbols of tyrannous social control — were colourfully reclaimed by gutsy, young, guerrilla painters.

As the techniques and designs of graffiti evolved from simple slogans and “tags” of artists’ names into imaginative murals and illustrations, the practice soon reached mainstream celebration: vandalism suddenly became art. In this context, beside Basquiat, Keith Haring and Blek Le Rat no one is more renowned than Banksy — a man whose very career is a microcosmic example of the art/vandalism conundrum.

Validated Vandalism

Banksy started out as a vandal like any other, illegally spray-painting witty designs onto other people’s property. But such is his escalation in notoriety, great consternation now follows any damage to his unsolicited works. His recent Valentine’s Day piece (stencilled on the side of a Bristolian house) was swiftly defaced, causing the BBC to carry the headline Banksy Mural Vandalised, without irony. Other of his works have frequently been “destroyed” by local councils, sometimes through policy, sometimes accidentally, sometimes by a confused combination of the two — most recently on the London Underground. Sometimes, Banksy’s work has even been destroyed by Banksy himself — most spectacularly when he remotely shredded a print of “Girl with Balloon” moments after it sold at auction for over £1 million. Immediately, art dealers claimed the act had doubled the value of the semi-lacerated piece — some incredibly valuable vandalism.

On the other hand, measures taken to secure Banksy’s work — either by private parties who own the property, or local authorities attempting to preserve these scattered pieces of art history — are themselves considered socially deviant, both towards the artwork itself, and the viewing public who can no longer freely access it. Amid all this multi-directional agitation, it is difficult to establish who exactly is doing the vandalising. Perhaps even more notable than his concepts or painting, Banksy’s great skill is to turn the tables on the powers-that-be, who suddenly seem like vandals themselves by attempting to profit from or disappear his work.

He proves that attractive, clever, or pertinent vandalism can be highly valued; no longer considered deviant if performed by the right hand. Far from offending the social fabric, it transcends social norms and typical comprehension of what is “vandalism” or “art”. It simply becomes a cherished representation of what a society wants to stand for.

By Banksy, London 2008

Nowhere is this better manifested than by the crayon, charcoal and chalk writings on the walls of Berlin’s Reichstag. Scrawled by Soviet soldiers in 1945 after beating the Nazis in battle, it would have been reasonable to remove the words and seek a “fresh” start. Instead, they were purposefully preserved in place. Persistently visible at the heart of German government, the graffiti serves as a profound reminder of the country’s present freedoms and painful history; a society demonstrably willing to confront itself.

Monumental Questions

Back to Bucharest, where the questions surrounding Memorialul Renaşterii and its evaporated haemorrhage remain: where did the most concerning act of vandalism occur? Across its chequered history, which public act was the most socially deviant? Conceptual vandalism, given the monument was commissioned by the very man who allegedly caused the deaths it seeks to mourn? Fiscal vandalism, by the amount spent on such a controversial project? Aesthetic vandalism, in its divisive design and placement? Ideological vandalism, by the person who tossed the paint? Civic vandalism, in the City’s failure to remove the paint for close to a decade? Or cultural vandalism, by finally cleaning it off after it had become an iconic element of Bucharest’s visual landscape and collective consciousness?

Where vandalism is concerned, the answers lie in the eye of the beholder. In trying to cleanly define something as “vandalism” or “art” we immediately risk losing sight of what “the thing” really is. The paint on Memorialul Renaşterii could have been neither, as much as it could have been both.

Crucially, such a deviant public act is never committed with the expectation it will survive for long. In that sense, this splash of paint achieved far more than the vandal could ever have anticipated. Astoundingly, I first saw the paint during its fifth year. It caused me — a random Scottish-Ghanaian — to look deeper into the monument and Romanian history than I might have otherwise. It stirred in me a multitude of thoughts and feelings, ultimately leading to this article, memorialising its demise. Even in its disappearance, its effects continue to reverberate. By reading this far, you too have become an active participant in the discourse it inspired, along with the millions who saw it and are unlikely to forget it.

With such an expansive impact, “art or vandalism?” no longer matters.

0 notes

Text

Take Your Time

During lockdown, our individual perspectives of time were shaken. If time is subjective, what do we do with it?

© Neal Gruer

Time and space are modes by which we think not conditions in which we live.

— Albert Einstein.

The defining feature of work as a commercial lawyer is not the suit, the intellectual discussion, the clients, the office politics, or the sloshing around of money. It’s something they never show in Suits or The Good Fight: the stopwatch. On every lawyer’s computer, a piece of software (unironically named Carpe Diem) provides rolling timers to be clicked on and off when moving from one task to another. Every moment is accounted for.

At the end of each day, the minutes and hours are shovelled into a database, where the lawyer writes a detailed narrative for every block of time. The information is then used to build an accurate bill for the clients and to assess how hard each lawyer is working. In an industry where work is charged for by the hour, every minute has an exact, predetermined value; both financially, and how each lawyer is viewed as an employee. Time is quite literally money.

As a lawyer, sometimes, I wished the clock would speed up, desperate for my hours to increase towards my monthly billing target. On other occasions, it whizzed past unstoppably as I strained to meet an imminent deadline or demonstrate my efficiency. Time was rarely a neutral experience. Recording every minute of every day for analysis by my superiors made me extremely sensitive to how I perceived time. Maintaining a balanced temporal mindset in these conditions was a battle; a battle against time — the constantly conspicuous overlord I could never overcome.

Until I did. Sick of stopwatches, after four years I left to follow my passions of photography and writing. Now, when I am freely roaming the streets photographing a new city or pressing pen to paper, I typically lose all concern for time. It still requires my consideration — to finish photographing before nightfall, or ensure I still eat at reasonable intervals in the day — but I am no longer forced to attribute an arbitrary numerical value to it, financial or otherwise. I acknowledge it exists but tend not to think about it. In doing so, my levels of day-to-day contentment have dramatically increased.

In the lockdown spring, this sensitivity towards time was laid bare for all of us — how it passes through us in wildly different ways, how we scrabble for a method to gauge it, and the enormous effect it can have on our emotions. But what can we do about it?

I barely know what day it is.

— Everyone, 2020

Through every lockdown conversation, the above sentiment became a running joke. Days were long, weeks were short, or vice versa. For some, April went extremely quickly, while for others, it felt like an age. In any case, the unifying feature was a sudden discombobulation in the way we perceived time. Under the pandemic’s grasp, our familiar time-markers disintegrated, replaced by an erratic Covid-clock. Outside of Italy, you may have followed how many weeks behind the boot-shaped island your country was from getting a kicking (“Two weeks ’til we reach 1500 deaths a day”). Perhaps your measurement was a lament of absent activities (“This would have been our third day in Istanbul”; “Next Saturday would have been our wedding day”). Alternatively, you may have watched the kilos emerge around your waist like tree rings as you ate yourself towards comfort.

No matter how you compiled your days, the confines of our own, limited perception mean we construct time on the basis of both the individual — how it feels, and the collective — the metronomic hands of the clock. The clock is physics-driven — an objectively agreed approximation of an extremely strenuous concept, variously comprising of the big bang, Einstein, gravity, the speed of light, black holes, entropy, the multiverse and Back to the Future. This idea of time and its relativity to space is difficult to get one’s head around. Perhaps it’s so difficult because arguably, both spiritually and scientifically, time doesn’t exist at all. Instead, there are only sequential events and tangible atomic changes, which we consciously witness and translate into “time”. In that case, “time” is a primitive form of expression — a language for something we have waived our need to fundamentally understand.

Given the challenge of understanding time on that level, most of us simply live based on Earth’s rotation. Other than for a handful of space-travellers, whose time has theoretically bent and slowed, we experience time only as far as it visibly appears in our day-to-day lives: day turns to night, trees grow and shed leaves, skin loosens from taught to wrinkly (unless you’re Rob Lowe). For this reason, we speak of time in the comprehensible terms of three-dimensional, physical space — “the party is after lunch”; “I’ll be there in 10 minutes”. Even then, language and culture have a meaningful effect on how we perceive that spatial construct. Do you characterise time in terms of volume, like the Spaniards (“a full day”); or distance, like the Swedes (“a long day”); or dispense with the linguistic concept entirely, like the Amazonian Amondawa tribe?

Time as a Feeling

Regardless of our rudimentary attempts to describe time, how it feels remains unique to each of us. Our memories, emotions, habits; body and brain function all play a role in how we perceive it. The feeling of minutes, say, from waiting for a train; hours, from hunger between meals; days, from waking up every morning; months (I daresay) from menstrual cycles; or years, from marking birthdays. In any given moment, a near-innate, biological “pacemaker” and measuring tools honed from our experiences combine to determine how long or short a period of time feels. These sensitive mechanics make our time perception deeply susceptible to external forces:

Time perception, just like vision, is a construction of the brain and is shockingly easy to manipulate experimentally… as subject to illusion as the sense of color is.

Brain Time, David M Egelman, 2009

To this end, it is well understood that when the brain processes a large amount of information in a short period, such as absorbing a new experience or enduring a traumatic event, we later recall time as having passed more slowly. As children, for whom everything is new, a two-week summer holiday feels endless. For adults, such a break can feel achingly short.

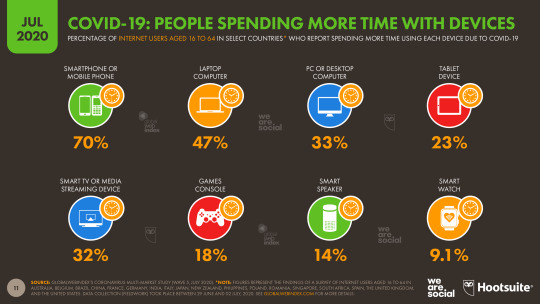

That said, these psychological mechanisms are still subject to each individual’s unique personality and circumstances. For example, loneliness has proved to be a significant factor in slowing people’s sense of time during lockdown, while a greater use of digital devices is likely to have sped it up.

In the latter case, technology disrupts our internal pacemaker and increases our stress levels: if you have an hour to complete a task and it feels like 50 minutes, you’re subconsciously pressurising yourself to do things 20% faster. Even without the ubiquity of digital clocks in the corner of every eye, it stands to reason that our Pavlovian response to bombardment by notifications changes how we digest time. And that’s before you consider how much we outsource memory (a crucial aspect of time perception) to our phones, without understanding the cognitive consequences.

© GlobalWebIndex / Hootsuite / We Are Social

Between Zoom calls, smartphone scrolling, working on a laptop, binging Netflix, repetitive tasks, adaptation to new circumstances and unusual social occurrences, any given lockdown day was liable to speed up or slow down by the hour; further assembling into weeks, which would slip through our fingers or linger indefinitely. Disorientating, yes, but also a valuable reminder that our perception of time is subjective, and therefore something we have a degree of control over.

Take Your Time

While compliance with the clock helps us interact with others and make a living, we should be wary of allowing it too great an influence over how we enjoy or endure our experiences. Frustration from waiting, pressure from deadlines, habitually arriving late or early — all these arise from the way we process time. Finding ways to free yourself from its yoke can be useful, not only in an uncertain era where another challenging lockdown might be just around the corner, but also as we return to more conventional ways of living. A warped perception of time — whether too fast or slow — has been linked to stress, anxiety and depression. Insulating yourself from a fluctuating perception of time serves towards a consistent mental state.

In practical terms, it helps to do any fulfilling or challenging activity with no incantation of time attached: distance yourself from technology, wander aimlessly outdoors, read from a page rather than a screen, thin out your schedule, study something new, write down your thoughts. When you cannot control your activities, mindfulness has been shown to help. Focussing on the present moment hypothetically minimises stimulation of your internal pacemaker; slowing your sense of time and allowing you to relax into whatever you find yourself doing.

Whatever your circumstances or interests, the key is to take your time, to the fullest extent possible. Take life at your own pace, whatever that might be. Avoid the agitation of scoring life based on time achieved or missed. Wind your own clock and be sensitive to what makes it tick. As an ex-stopwatch jockey, I attest to its benefits.

youtube

0 notes

Text

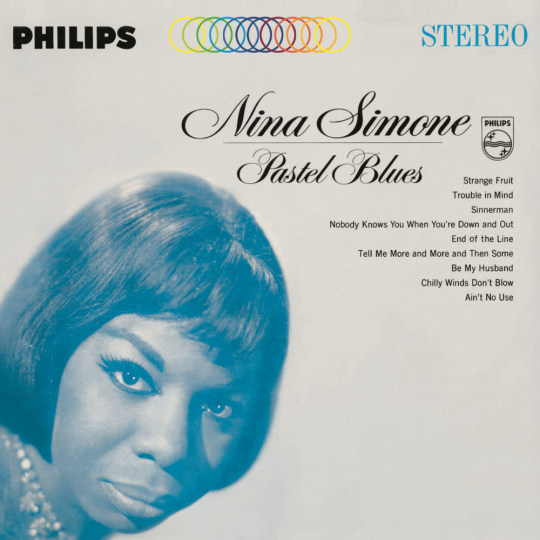

Nina Simone, Duende & Pastel Blues

Nina Simone’s Pastel Blues is a true embodiment of duende — the rare depth and darkness that impels her work.

1969 © Jack Robinson / Hulton Archive

Her distinctive warble permeates thousands of movie soundtracks, hip hop samples and advertisements, let alone the countless personal moments by which people demarcate their lives. This omnipresence allows us to forget who Nina Simone was, and the outright value of her music. For the streaming generation, knowledge of such an artist is limited to “top hits”; on some Spotify, Sunday Mood playlist. Or worse, the songs will only wriggle into the brain from various attempts to sell Coca-Cola, Seat Atecas, Renault Clios, Volvo XC90s, Fords, Apple Watches, Chanel №5, Warehouse discount clothes, Virgin Flights, HTC Phones, Jockey underwear and Behr Paint.

Most egregious among these is the Muller Light yoghurt advert, inescapable for anyone sentient in early 2000s UK. It uses her 1968 song I Ain’t Got No, I Got Life, but only the second, I Got Life half; carving it off entirely from its I Ain’t Got No essence. In its truncated form, the song sounds like a free-wheeling celebration of life and limb: Got my hair, got my head / Got my brains, got my ears / Got my eyes, got my nose / Got my mouth, I got my smile. Yet the missing section is a lengthy condemnation of segregated American society, where disenfranchised black people had been given nothing to cling to: Ain’t got no mother, ain’t got no culture / Ain’t got no friends, ain’t got no schoolin’ / Ain’t got no love, ain’t got no name /…Ain’t got no god / Hey, what have I got? / Why am I alive, anyway?

Yes, the song contains positivity in tune and verse, but stripping the darkness from Simone’s work also strips away its incandescent light. It would be like taking Rodin’s Gates of Hell and shrouding everything except the seemingly peaceful thinker at the centre; or cutting the lightbulb from the top of Picasso’s Guernica and presenting it as a bright, merry, representative segment. Or a millionaire DJ taking Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream Speech and turning it into a dance track during race protests and a global pandemic. But surely not even David Guetta would do that.

The reduction of such a deliberate and profound artist to commercialised snippets is saddening. In Simone’s case this is particularly true because of the highly unusual, powerful darkness that clutches her music. She has something rare. In Spanish, it is known as duende.

Duende

Rooted in Iberian cultures, duende derives from “duen de casa”, meaning “possessor of a house”. Originally the superstition of a dark, goblin-like spirit, it is now the concept of impassioned, death-endorsing, creative invention; typically associated with the performative aspects of Flamenco. In that context, poet and playwright Federico García Lorca describes its contemporary meaning (in his 1933 Buenos Aries lecture, Theory and Play of the Duende), as the “buried spirit of saddened Spain”.

As a guitar maestro explained to him, “the duende is not in the throat: the duende surges up, inside, from the soles of the feet”. Lorca quotes others, one, after listening to Paganini’s violin, identified it as, “a mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained”; or another, upon hearing Manuel de Falla perform Nocturno, proposed that, “all that has dark sounds has duende”. In Lorca’s own words:

For every man, every artist called Nietzsche or Cézanne, every step that he climbs in the tower of his perfection is at the expense of the struggle that he undergoes with his duende. Not with an angel, as is often said, nor with his Muse…

…With idea, sound, gesture, the duende delights in struggling freely with the creator on the edge of the pit. Angel and Muse flee, with violin and compasses, and the duende wounds, and in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of a man’s work.

Nina Simone embodies duende.

1968 © Hulton Archive

It exists not only within her more explicit protest songs, born of the Civil Rights movement, but is present in everything she did — a ferocity, fragility, sadness and authenticity that claws its way up her throat and flings itself from her open mouth. It’s an otherworldly channelling of something very few can access, but which audiences pray to feel. With music so steeped in darkness, using it to gleefully sell products is a comedy — a joke on the shamelessness naivety of consumers and marketeers — as well as a tragedy.

A Brief History