Text

Modern Love: He Made Affection Feel Simple

[courtesy of Brian Rea]

"Dating as a transgender woman, in my experience, meant low expectations and casual sex. Then I met Jack."

This piece is part of the Modern Love column at The New York Times

by Denny

My bio on Grindr read: “Be trans friendly. Send face to chat.”

It was difficult to be on a gay hookup app as a trans woman. Most men in my feed desired to only sleep with each other. But I knew there were straight men on Grindr who hungered for a woman like me. I wanted them too.

That’s where I met Jack. At 22, he was a few months older than me, and, other than his age, his entire profile was blank, usually an indicator of a cisgender straight man who was guarded about his attraction to trans women. Typically, the messages I received would start with a vulgar sext, sometimes an unwanted nude photo.

Living in Morningside Heights, I was attending Fordham University for my master’s degree in strategic communication. One night I was up late working when I received a Grindr message from him, a selfie. Amid his light brown hair, two-day scruff and meek gaze, his lacrosse T-shirt stood out to me the most. He looked like a sporty boy I would have crushed on in high school.

He followed up his photo with “Hello.”

Messages in my Grindr inbox tended to cut to the chase: “Down for now?” “Car sesh?” Men who contacted me because they fantasized about trans women made it difficult for me to feel seen as a person in general, let alone a person worthy of respect.

Although my interest was piqued by Jack’s picture, it was his gentleness that drew me in.

Our sporadic small talk was harmless, spanning two months. I brushed him off, but as I commuted to school and spent hours in the library, he was persistent.

“My sex drive is pretty low these days,” I wrote. “Give me a bit and I’ll hit you up.”

“OK.”

When I turned back to my studies, he added, “Just so you know, we can do non-sex things and hang out too. It would be fun.”

This became our pattern: he being distant enough to show interest without pressure, and me appreciating his laxity, given my demanding schoolwork. His ease led me to trust him, so we set up a day to meet.

The first afternoon Jack came over, he admired my bathtub and drank his cup of water with two hands. His poised demeanor in a beige wool peacoat and long scarf reminded me, in a good way, of John Bender in “The Breakfast Club.” In my bedroom, he fixated on my yellow Power Ranger figurines, noticing my framed academic award next to them on the windowsill.

“You went to SUNY Oneonta?” he said. “I went to SUNY Potsdam.”

I pictured my friends who also attended Potsdam eating in the same cafeteria as Jack, getting drunk at the same frat party. Suddenly, the person I’d seen as a stranger now fit into my world.

I imagined what the deer looked like from his dorm room window, roaming the grass at dawn. Or how he spent his day when the school canceled classes because of snow. Or where he would have gone if his parents were able to afford private school.

We sat on my bed, my back leaning against the wall. He slouched his head onto my hip and wrapped his arms around my waist. “This is weird,” I thought. Aside from sexual intimacy, my hookups were typically aromantic, absent of cuddling and expressions of affection.

I kissed him and rolled on top. I took off my shirt and he hugged me tight. His face dug into my chest as he said, “I like you. I think you’re really cool.”

Unsure how I actually felt, I said, “Oh. I think you’re really cool, too.”

The next time I saw Jack, he spent the night at my place. It was then, awake in bed at 4 a.m., that I realized I had never let a guy sleep over before. His heat warmed the bed, so I crept to the bathroom to cool off. I Snapchatted a disoriented selfie to my friends, my hair messy and eyes bloodshot.

“How do you guys do this sleepover thing?” I wrote. “I can’t sleep at all.”

Customarily, my flings with strange men were brief. The men did not take note of my bathtub or my educational history before sex, and they did not linger after.

I came back into bed, disturbed by the rumble of his snoring, but his sleeping face on my pillow struck me. For the first time, the thought of sharing a bed with a man did not come from pure imagination. I now had a real image for this fantasy; I could pretend Jack was my boyfriend, reach for his face and whisper “I love you, good night,” then fall asleep and meet him somewhere in his dream as if we had done this a hundred times before.

The next day, he flew off to see his family for the holidays and the first weeks of the new year.

“merry crimmus,” I texted.

“u too, babygirl,” he replied.

After our sleepover, I didn’t hear from him unless I initiated — an unexpected change. Instead of giving in to my insecurity that the sleepover meant little to him, and therefore I meant little, I imagined other scenarios: him asking me to sleep at his place, for a change, or spontaneously calling me while I’m in line for my morning coffee. But because I had presumed a sex-only expectation from the start, I shamed myself for developing feelings.

“miss u,” he texted one random morning.

“really?”

We stayed in touch and occasionally saw each other, weeks in between. On a hot morning, he snored behind me as I sat on the floor beside my bed, working on my final thesis. He put his hand up to my face, letting me know he was awake. With my eyes on the laptop screen, I took his hand and planted kisses in his palm, wallowing in these ordinary joys — the kind of affection I slowly grew comfortable displaying.

Longing to be more than casual with him, I sought a therapist to guide me through my growing feelings.

Jack’s periodic “miss u” texts progressed with heart emojis, an unprecedented closeness. And I returned the sentiment. It felt thrilling to express my adoration so directly, until the weeks between seeing each other and texting ultimately turned into months of silence I knew to be ghosting.

I relied on Grindr as my safe dock because dating as trans is complicated. Sleeping around was easier for me. I had set the bar low, then met Jack, who saw me as more than a fantasized body, only to have his mysterious exit echo a looming insecurity I avoided for years: Being trans implies I am not real enough to deserve decency.

I broke down in therapy, mustering the courage to say out loud what was undeniably true: “He left me.”

“I don’t mean to put this on you,” my therapist said, “but could him being a cis straight man and you being a trans woman play a part?”

I didn’t want to blame Jack, who showed me a new realm of affection that made desire feel as simple as just a boy and a girl who liked each other. But he made leaving simple, too; all of this could still not be enough.

Deep down, I denied how my mere existence as a trans woman could ever cost him. Jack, in wooing me, nurtured the possibility that my romantic fantasies could come true, that I could be seen as a complex person rather than a fetishized token of someone’s imagination. After being deserted by him, I ruminated on my insecurity that being trans denied me of even a simple goodbye.

And yet I know myself to be real because my transition, as a teenager, required exceptional certainty. Doctors and psychiatrists double-checked my decision constantly.

“Yes, I’m sure,” I repeated, and I became more real each year. With Jack, I felt even realer. Not only had he seen me as a woman, but as a woman worthy of being held.

I could blame my being trans for Jack’s ghosting, but maybe it had nothing to do with that. Maybe he hated his job. Maybe his family fell apart. Maybe the pleasure we felt together contrasted whatever pain remained of our baggage.

On lonely days, I imagine myself at SUNY Potsdam. At a frat party, I drunkenly dance across from Jack, cheap blue lights grazing the curves of our cheekbones, sweat dripping like cyan fireflies. Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline” roars through the party. “Good times never seemed so good,” everyone shouts. “I’ve been inclined to believe they never would.”

I put myself in the cafeteria, where Jack and I approach the salad bar at the same time. When he sees me, he steps back and says, “You go first,” with a grin so big I would need both hands to hold it.

———

Denny is a writer, actor and musician living in New York City.

#modern love#ML#NYTimes#New York Times#The New York Times#Amazon Prime#dev patel#anne hathaway#tina fey#NYT#trans#trans dating#trans love#lgbtq#pride#grindr

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexis Nikole, The TikTok Forager

This piece is part of the Person of Interest vertical at @bonappetit

Alexis Nikole considers her TikTok fame a fortuitous accident. She knew nothing about the platform until she started an account for her day job as a social media manager. But when the 28-year-old from Columbus, Ohio, began experimenting on her personal page during the pandemic, she got more than she bargained for. Specifically: over 600,000 enthusiastic followers and 10.3 million likes.

Since April of last year, Nikole’s now viral account has been showcasing her immeasurable knowledge of foraging and cooking with wild plants: a sorbet made out of Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), hairy bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta) turned into lush salads, and common dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) battered and fried like fritters. She studied environmental science and theater at Ohio State University, and often combines her two passions on the platform—where you’ll find her singing original songs about cattails and sassafras.

By sharing excellent foraging tips laced with undiluted humor, Nikole’s intentions were for people to take agency over their meals and make the most of foods that were free and readily available all around; especially after COVID-19 hit American shores and shopping was anxiety inducing. During the early months of the pandemic, Nikole’s TikToks focused on how foraged goods could extend groceries and increase access to fresh ingredients, especially for those living in food deserts. This is precisely why Nikole’s videos are so grounding; in these times, it’s crucial to feel some sense of self-sufficiency and stability.

Amid global adversity, Nikole forages because it reminds her that she’s human—and humans, at their very core, are part of the ecosystem, no matter how much we distance ourselves from that truth. I called up Nikole to learn more about her foraging background, how she practices gratitude for what is all around, and why the world needs more hyper-localized food systems.

Foraging makes me feel I am a part of something bigger… and that feeling is really good at chasing the depression away. Typically I go out between two to five times a week on average. In the dead of winter, I might only go once, and during the dog days of summer, I’m in the woods and nearby parks every single day. I’ll jam to ’80s funk the entire walk to the creek, but the earbuds go away when I get there. I want to hear everything—the crunching leaves under my feet, the babbling brook, and people conversing and laughing in the distance.

I used to dream of being a pop star… by night and a scientist by day. I’ve been surrounded by music for a long time. I was three when I joined the childrens’ choir at my dad’s Baptist church, I started classical piano at age five, I was in choir every year through junior high and high school, I performed a cappella in high school, and was on the e-board of ukulele club in college. I was never a prodigy, but music brings me so much joy, so I love being able to sneak that into my TikTok videos.

The best meal I’ve made using a foraged ingredient is probably… chicken-of-the-woods mushroom (Laetiporus sulphureus) “crab cakes” and an American sea rocket (Cakile edentula) and steamed beach pea (Lathyrus japonicus) salad tossed in olive oil infused with goldenrod (Solidago). Very gourmet!

My curiosity for the outdoors… was nurtured from a very young age by my parents. My two sets of grandparents knew that scouting was good for building connections and recognized the importance of getting outside, and thus got my parents into it early. My mom scouted longer than my dad did and went to sleepaway camp in New Hampshire in the summertime. Eventually, while working at Procter & Gamble, she gardened on the weekends to decompress. I would help her, spreading mulch or digging into the earth with a tiny trowel while she quizzed me on the plants. Unbeknownst to my mom, I was picking up a lot of information. From there it grew into a love of all things growing plants outdoors.

You don't have to go full forager… to reduce your environmental impact. Over the past few decades society has trended away from a localized food system, toward a global one. On the upside, it’s much easier to find ingredients like star anise at the grocery store. However, access to tomatoes year-round means they’ve got a higher carbon footprint because they traveled thousands of miles to get to your plate. Even shopping at your local farmstand helps with lowering your carbon footprint; it’s also a little easier than identifying a plant and bringing it home to eat.

Everyone was afraid of going to the grocery store… when I started my TikTok foraging videos in April 2020. So I thought: Hey! Here are a few plants that are really common and probably growing in your neighborhood that you can gather, and maybe that’ll stretch your groceries a bit.

Poor and POC communities are hit hardest… when major disasters hit. We saw the same thing playing out in Texas with the massive winter storm. So I offer my knowledge to help someone who needs to get some fresh food on their plate.

As a Black, queer female forager on the internet… I’m not the person people expect to see excited about foraging, the outdoors, biology, botany, and history. I have delightful forager friends who are white, and I notice they don’t get questioned nearly as much as I do. That’s heartbreaking. When my dad learned that my account becoming viral also meant me becoming susceptible to online harassment, he got angry and told me, “I’ve been alive for 65 years. It doesn’t feel good that you’re still called into question because of who you are.”

Though, it all feels worth it when… a follower sends me a thank-you message saying, “Because of you, while I was out walking I recognized this plant and it made me feel like my neighborhood was a cooler and happier place.” To be less unacquainted with plants or more connected to surroundings because of me is a huge win. We take better care of the things we know.

#bon appétit#bon appetit test kitchen#bon apetit#BA#BATK#healthy#health#healthyish#person of interest#poi#Alexis Nikole#AlexisNikole#blackforager#forage#forager#foraging#qpoc#TikTok#TikTok forager#vegan#TikTok Vegan#Ohio#TikToker

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

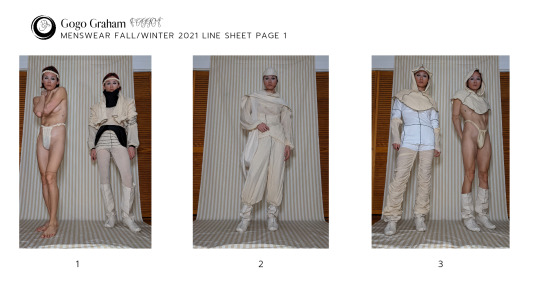

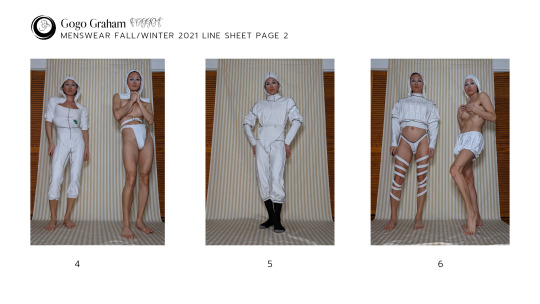

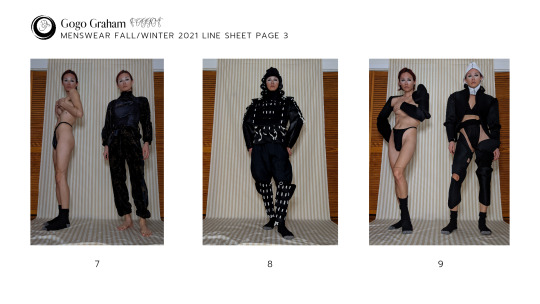

Gogo Graham Debuts Her First Menswear Collection

This piece is part of the Fashion vertical at @papermagazine

At the start of this year, Gogo Graham uploaded an Instagram post asking whether she should start a menswear line, prompting an overwhelming response of "yes" from her followers intrigued by the prospect. ("I'm just calling it that, clothing doesn't have gender, everyone can wear what they want!" she later assured one user in the comments.)

[Credit: Gogo Graham]

She soon began thinking about the men and masculine people in her life who've supported her work since its inception, which has long been known for prioritizing and celebrating trans femininity in the world of fashion. But the thought of transfeminine people being the primary source of her design income compelled to initiate change. "I actually think men should be the ones supporting my work financially," Graham says.

The result is the launch of FAGGOT, her first foray into menswear that coincides with the debut of her Fall 2021 collection "Sissies Pay Me to Tell Them What to Wear," a fantasy of what Graham herself wants men and other masculine people to wear. (She models the collection throughout in the lookbook.) It's medieval-meets-samurai, squire-meets-court-jester, mainly inspired by the Renaissance festivals wherein men dress as knights and squires.

[Credit: Gogo Graham]

Although this is her first official menswear collection, it is not the first time she's dressed men before. The collection's title stems from her work on OnlyFans, where Graham asks her subscribers (mostly cis, straight men) to buy and wear women's garments for her as part of their consensual, paid relationship. Always with a clear policy to communicate any discomforts throughout their interactions, Graham starts by asking her subscribers: "Have you ever worn slutty underwear or thongs?" (Responses often vary from "No, but I'm interested" to "Yes, I like it.")

"Submissive men like to be told what to wear," Graham says. "It's exciting for them to experiment with gender and not feel shame about it." Still, the shame is still very much prevalent in straight men's relationships with the trans women they desire — Graham included. "A lot of men are afraid to date [trans women]," she acknowledges. "So a lot of their interactions with the community are through sex work."

[Credit: Gogo Graham]

Indeed, men dressing in women's underwear is symbolic of the many secrets straight men keep private; a yearning worn in discretion, like a pair of panties underneath layers of clothing. If you protect yourself well enough, nobody will say you're a "faggot." But the derogatory term does not discriminate against gender; even cis, straight men can be called a "faggot," be it as trivial as their choice of shampoo or as grave as their choice of women. The difference is that "material objects don't possess gender," Graham says. "People do."

The release of FAGGOT and its debut collection "Sissies Pay Me to Tell Them What to Wear" is Graham's way of meeting men where they are. "Psychologically, it seems as though [the term] 'menswear' is a permission for men to feel like they have access to clothing, in spite of the fact that clothing has no gender and has always been accessible," she says.

Although a menswear line is new for Graham, it's also a way to engage her two audiences — trans women, nonbinary people and queer men from her mainline; and cis, straight men from OnlyFans — under a new umbrella. Ultimately, this collection is a sanction and invitation to venture out of the artificial etiquette of gender performance, something the designer has long championed and will continue to do.

#gogo graham#nyfw2021#fw21#fw 2021#fashion week#menswear#onlyf@ns#trans#trans fashion#lgbtq#paper magazine#samurai#squire#court jester#medieval#nyfw#fall winter 2021

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trans Inclusion On Screen Is Progressing—But to the Detriment of Black Trans People

This piece is part of Well + Good’s Healthy Mind vertical

“We’ve come a long way as trans actors,” claimed one of my fellow panelists during an LGBTQ+ actors’ workshop I was a part of. She wasn’t wrong, but it wasn’t the full picture.

“There is a gap, though,” I added. Yes, the portrayals of trans people on screen have improved from 20 years ago, when I watched the commodification of black trans women on TV shows like Maury and The Jerry Springer Show. But if “progress” is trans actors portraying trans characters on Sense8, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, and Euphoria, then it seems to have come at the cost of Blackness.

I was a senior in college, and serving my second year as the theater club’s president, when screenwriter, director, and producer Ryan Murphy announced the cast of his show Pose would include trans femmes of color: MJ Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Dominique Jackson, Indya Moore, and Hailie Sahar—all of whom are Black. As an Asian actress, I envied the actors and thought, Why not me?—which speaks to the collective misinterpretation of equity as a shortage of opportunities. My jealousy was greedy and unjust, insensitive to the pre-existing boxes and limitations of acting jobs for Black trans people.

Unprecedented casting aside, Pose still centered its characters’ stories at the intersection of being trans and Black. It wasn’t portrayals of gendered “trickery,” as it had been on Maury and The Jerry Springer Show, but the storytelling was still focused Black trans women’s pain.

Meanwhile, white actors are granted opportunities to tell stories that go beyond their gender. In Sense8, Naomi, played by Jamie Clayton, is a hacker in a fiercely committed interracial relationship with another woman. Although Naomi’s transness is acknowledged and honored, it is not the center of her story. In The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, trans masculine and non-binary character Theo, portrayed by Lachlan Watson, has a brief scene of coming out to his friends, who effortlessly begin to use the pronouns “he/him”,” and it’s barely a plotline; he continues to be part of a larger story about Sabrina, a teenager caught in between her witch life and her mortal life. Both Naomi and Theo are white.

And in Euphoria, Hunter Schafer plays Jules, a high school student whose story acknowledges her transness intentionally, as a way of combating the possibility that others might dismiss her transness because of her privileges. During an interview with BUILD Series, Schafer herself acknowledged: “It doesn’t go without saying that I’m white, I’m skinny, and I pass.”

So, what does it mean to say things are better now for trans actors? It means disregarding the fact that white trans stories have profited from Black trans women’s struggle to be seen. It’s a false privilege to say “look how far we’ve come,” when “we” does not include Blackness and Black trans women still strive for the same nuanced progress in TV and film.

“The privilege of being a white trans character is that only the trans aspect needs addressing,” says James Robinson, LCSW, a Black and white biracial therapist in New York City who practices psychotherapy with artists, largely of color. He indicates, on the other hand, how the acknowledgment of race is a tightrope balance in itself. “It’s hard to portray Black characters in general; if they aren’t portrayed in experiencing trauma, then the audience might resist and the story might receive backlash because of a denial to that character,” says Robinson. “And if you do acknowledge their trauma, then in some ways the character becomes a monolith.”

As an Asian trans woman, I fall outside of the white trans representation, but as an actor, I have been able to benefit from the work of the Black trans women who showed themselves on screen before me. I felt this firsthand when Black trans women were in the audition room for a short film lead role that eventually chose to cast me. I’ve even been complicit in the ignorant celebration of white trans actors making their way in the industry as just “trans actors” and not “white trans actors.”

Psychologist Justin Hopkins, PsyD, who specializes in trauma-informed care for individuals whose identities are on the margins, says the issue is complex. “No trauma ever begets or justifies another trauma. There are simply varying degrees of pain that yearn and demand the fullness in which they are experienced,” he explains. “As white trans people recognize their desires to be visible, it is still harder for their black trans counterparts to have what [they themselves] thirst for.”

And the art of acting in itself plays a role in people’s personal hunger to be seen. “People pursue any types of jobs and passions in which they feel driven from a soul level,” Dr. Hopkins explains. “If you are someone who spent your life being invisible or having aspects of your core identity denied, it can feel incredibly rewarding, although demanding, to have a vocation where you are seen, praised, and affirmed under the bright lights. There is something satisfying and gratifying to the ego—perhaps necessarily so.”

It is no coincidence trans actors feel driven about their career; it is cathartic to deliver a performance and feel recognized in return, especially when celebrated in masses. However, that is no excuse for letting the trajectory of on-screen success irresponsibly move in a direction that leaves Black actors behind.

So, I want to ask trans actors who are not Black: What’s in it for you? Can you fight just as long and just as fiercely as you are now if you get nothing out of this? Can you agree you have been benefiting from the path Black actors paved?

This is not to say trans representation on-screen isn’t improving. It is crucial for non-Black trans actors to acknowledge the racial gaps in the progress. To fight for our Black trans kin and expect nothing in return. To acknowledge what it has taken to get to where we are in the industry. And, at the very least, to responsibly pay forward what is owed.

#healthy mind#well and good#well + good#psychology#twoc#trans women of color#POSE#POSE on FX#mj rodriguez#indya moore#dominique jackson#hailie sahar#angelica ross#janet mock#transgender#trans#mental health#trans representation#ego#actors#theatre#trans actors#euphoria#hunter schafer#the chilling adventures of sabrina#lachlan watson#sense8#jamie clayton#caos#caos 4

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

”kiLLinG iT” during a pandemic 😰

to get the shiny milestones out of the way: i did my first commercial for real techniques. in june, i contributed to the team of organizers for the Black Liberation March for black trans lives, writing the rally script for the two hosts for 15,000 people to witness. i got to represent the state of new york for teen vogue’s 50 states of pride. i published an essay to syfy wire’s fangrrls column on avatar: the last airbender’s princess yue and her connection to the women in my family (um, and roxane gay congratulated me?) a short i filmed for in philadelphia early 2019, directed by iris devins, made it into this year’s outfest, an lgbtq+ film festival based in los angeles.

i admit most of these accomplishments bring me more humility than pride, as they are all public and make me feel separated from the very people i want to be closer with. not necessarily by the very act of interacting with my work, but by the digital performance of expressing congratulations on the internet (as online interaction is the most we can do in these times). is yas queen really a compliment lol 🥴

uh, anyway here are things i’ve been unapologetic about:

brain spew

every morning since april, i write at least one page of whatever weighs on my heart. before i interact with the world, be it online or in person, i make it my responsibility to check in with myself on paper. some weeks, the same weight loops over and over again day after day, and i let it.

justifyingbasichumanityisnottherealityiwanttokeepfightingforforever

it is irresponsible to think what is happening in the u.s. is acceptable. anti-blackness is a pandemic that’s lived long before the viral pandemic we are in now.

noms

it’s food. tacos and toast. what else is there really to say lol.

a breather from the city

i loved it here. i was scared because there weren’t a lot of brown and black people around, but i was kinda relieved people weren’t around in general. thx bri! ✨🥰

my bootiful brudder 💞

i luv my bootiful brudder.

#covid19#covidー19#blm#brooklyn liberation march#brooklyn#lgbtq#trans#transgender#anti-blackness#black trans lives matter

0 notes

Text

Avatar: The Last Airbender’s Princess Yue and the Cycle of the Sacrificing Woman

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

This piece is part of @syfy‘s Fangrrls vertical

Amidst the atypical state of the quarantine, the release of Avatar: The Last Airbender on Netflix has given me and other fans of the series something familiar to hold onto. In revisiting this favorite childhood show of mine, I sought Princess Yue's storyline with clarity. Although brief, it strikes all too familiarly; like the legacy of the women in my family, Princess Yue speaks to the aptitude of women who sacrifice.

Princess Yue is the daughter of Chief Arnook and his wife, a tribal chieftain. Unlike the other babies of the Northern Water Tribe, Yue was not born wailing. Sick and weak at birth, she could barely open her eyes. Members of the water tribe believed Yue was destined to die. Defeated, her father begged for his daughter's salvation before the moon.

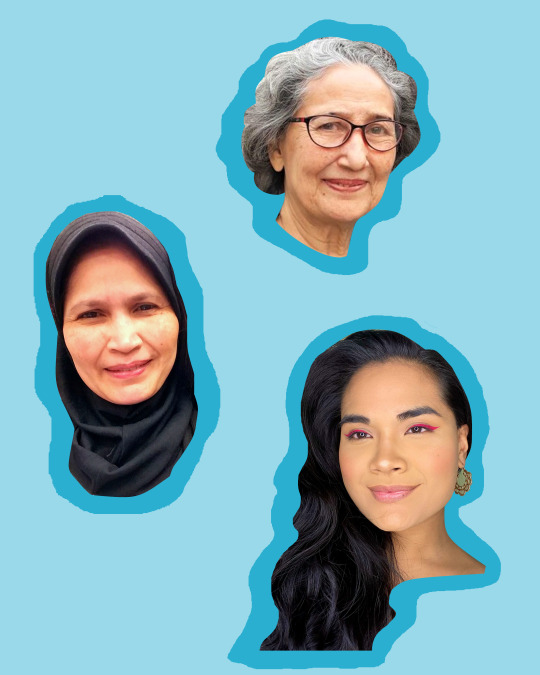

When my Dutch grandmother was 9, her father was assigned to Indonesia as part of his government service job. She and her family relocated to the city of Padang, the capital of the West Sumatra province. Not long after the relocation, her mother died of cervical cancer. With the new absence of a mother figure and lack of familiarity with a new country, adapting was her sole option to fight for what remained of her future and family.

While Yue and Avatar's main protagonists Aang, Katara, and Sokka look out into the night sky, Yue explains her own relationship to the moon. "My father pleaded with the spirits to save me," she recalls to the other three. "That night — beneath the full moon — he brought me to the oasis and placed me in the pond. My dark hair turned white. I opened my eyes and began to cry, and they knew I would live. That's why my mother named me Yue. For the moon."

Before my grandmother married my Indonesian grandfather, who is Muslim, she converted out of Christianity. Having already left Holland, her conversion to Islam established the new life she would soon build with the man she loved. It was a sacrifice of her ancestry only she could understand. It was a sacrifice not only out of circumstantial choices but also out of promise.

For this reason, I see my grandmother as the moon of our family tree. In Avatar, Yue says, "[...] the moon was the first waterbender. Our ancestors saw how it pushed and pulled the tides, and learned how to do it themselves."

Like a moon, the cycle repeats itself.

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

My family and I immigrated from Indonesia to the United States in 2007, leaving our extended families behind, including my grandmother. Approaching U.S. Customs at the airport, my mother took off her hijab, erasing the marker of her Muslim identity. She was nonchalant, but I remember it as clear as the blue sea.

"[In Indonesian:] I was OK with it", she recently explained to me over the phone. "I was searching for ‘safe'. I didn't feel pressured or forced to." Although firm in her strength in recalling her feelings, I heard the shake in her voice. She sounded like water.

"I felt guilty," she admitted. "Sometimes I get sad seeing women who are brave enough to wear hijabs out in public. It makes me jealous."

"What does Dad say?"

"He says, ‘What makes you feel more at peace — follow that path.'"

I understand where she gets her integrity from. Listening to her and feeling my grandmother in my mother's conviction felt like witnessing the moon and ocean in motion. In this, I saw the spirits of Tui and La.

Tui and La mean "push and pull," Spirit Koh, one of the most knowledgeable spirits in the Avatar universe, tells Aang. "And that has been the nature of their relationship for all time [...] Tui and La — your moon and ocean — have always circled each other in an eternal dance. They balance each other, yin and yang."

Considering America's anti-Islam rhetoric after 9/11, my mother did what she deemed necessary at the airport. In order to enter America smoothly and without the religious bias of those who had power to accept or deny our entry, she sacrificed a visible part of herself, a momentary surrender with the promise of resistance.

Before moving to the States permanently, we moved throughout the Indonesian islands frequently, too. Traveling was meaningful not only because it gave us fond memories, but because we traveled as a unit. My mother always dreamed of having a family of five, so she had three children — me the youngest. As a nuclear Indonesian family, moving to the United States would allow us to achieve the American brand of success. However, the adjustment of living in America altered our standing as a family, breaking my mother's picture-perfect family mentality.

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

In Book 1's finale of Avatar, the Fire Nation invades the Northern Water Tribe as part of their greater mission to take over the world. Leading the Fire Nation Navy, Admiral Zhao kills the moon spirit Tui, whose physical form was the white koi fish. The Northern Water Tribe loses its balance and therefore the ability to waterbend.

Moving as a kid wasn't so much a sacrifice for me, but transitioning was. My sacrifice rifted with the sacrifices of the women before me. My transition felt selfish and destructive to my family.

Aware the moon's power remained inside of her since her father's plea, Yue gives back her life to save Tui, the white koi fish. Yue's sacrifice restores balance, even at the cost of herself. But Yue does not die — she reemerges as the Moon Spirit. She reminds her lover, Sokka, "I'll always be with you," before fading into the moon.

Oftentimes, I sense a familial grieving of the person I once used to be. Reintroducing myself to the world, saying, "I am a girl," does not discount who I was and am in spirit. Sacrificing my past froze my family rather than propelled. But ice is still a form of water, and time thaws.

When my dad took away my makeup as a denial of my femininity, I sat on the stoop of our house. A house in America, occupied by Muslim immigrants, descendant of an interracial marriage. We've come so far from where we began, yet it was everything I never asked for. My mother stepped outside to sit with me and slipped me a $100 bill.

"Go buy new ones," she smiled.

My grandmother, mother, and I sacrificed our legacies across oceans, religions, and genders. The act of sacrifice cycles itself down generationally. Like the moon, we set to rise. Like the ocean, we ebb to tide.

These days, I find it easy to accept the coexistence of contraries. Accepting my life as a woman required the rejection of what my family believed I ought to be. When I see more and more of my mother in my reflection, it is not because we are women. It is because we sacrifice. She understands the selflessness of surrender, and I know she learned that from her own mother; to give for the taking, to hide for the priding, to shed for the sprouting. This duality keeps the world spinning.

After Yue's sacrifice, her father, Chief Arnook, professed to Sokka as they stared into the moon's horizon: "The spirits gave me a vision when Yue was born. I saw a beautiful brave young woman become the moon spirit. I knew this day would come."

"You must be proud," Sokka responds.

"So proud. And sad."

***

[Credit: Decoding Ellipses]

#avatar#avatar: the last airbender#ATLA#avatar the last airbender#aang#katara#sokka#yue#princess yue#tui#la#spirit koh#admiral zhao#moon spirit#moon#sacrifice#lgbt#trans#transgender#syfy#fangrrls#syfy wire#yin and yang#tui and la#tui la#waterbender#tlok#the legend of korra#avatar: the legend of korra#korra

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Distancing Isn’t Burdensome. Solitude Is.

I hold out to the temptation of yet another YouTube video I’ve seen thrice within the past week, and reluctantly go to bed. My room snaps dark and silent, and I let my mind patronize the way I’ve spent my time because it’s an easier topic to land on. By the time I sleep, it’s 6 am.

I start my days with a shower to wash off hang-ups from the night before. Let’s start again. My dad calls me as I dry myself, and I stare at my phone. He then calls me over video and I remain without a flinch.

I fix my lunch in the kitchen. The stove and the oven are on at the same time. I turn on the stove fan to air out the smell of food, and mock the pitch of the fan. I harmonize with it and laugh to the sink. My mom texts me saying We want to video chat with you, and I turn up the stove fire.

I re-download Instagram and Twitter just to check if there are any emergent notifications. I watch the numbers of messages I ignore go up, and snicker. I uninstall them. I’m not really missing anyone. I feel obligated to miss people considering I can’t see them, but I fight the notion just to feel like I’m right even if it’s allusive.

The quarantine has been tough for a lot of obvious reasons I’m sure you are aware of; structure, money, uncertainty, restriction, and the collectively used phrase, social distancing. According to the CDC website, social distancing entails “keeping space between yourself and other people outside of your home [...] at least 6 feet (2 meters) from other people, not in groups and crowded places.”

In my practice, social distancing has been the easiest of the quarantine. Away from the grind of “work hard, play hard”, taking time off of some responsibility feels alleviating. There is, however, a looming weight that has no tie to work or physical health. Being six feet away from people doesn’t take away the irony that I can’t do the same with my feelings. Social distancing is not the burden. Solitude is.

My mental and emotional confrontation with myself limbos my work-related rest. Catching up on sleep feels disheartening when I spend my waking hours avoiding what really boils below the surface.

What concerns me above all was my autopilot prioritization of physical and financial survival pre-quarantine. Work overtook my direction, and any self-related inner work constituted as additive, and although admirable - not substantial. Sitting down for therapy 45 minutes once a week allowed me to reel in the gravity of my pace, even when I was reluctant to open up. My solitude realizes the selflessness of working a job. It realizes the (slow and small but) significant progress of therapy, and some days feel it even going the opposite direction.

The feelings are simple: I’m still hung up over the unresponsive fade of someone I really liked, and I’m oftentimes bitter that my talents are an unseen potential to people who have power to propel me to a full-time artistic career. When the world encourages a physical pause, my personal feelings run double the playback speed. When we resume working, will we resume the same habits? It’s taken me a global pandemic to face grief and frustration, not even in its entirety at best.

I’ve no denouement for the things that make me human. I go to bed after hours of movies and YouTube videos, accept the grief when my mind hits quiet, and fall asleep five minutes later. I call my parents back while eating lunch like I miss talking. I don’t. At least not right now. I spend the first two hours of waking up hugging my pillows. I’m already tired.

#social distancing#solitude#coronavirus#covidー19#covid#quarantine#trans#lgbt#decodingwomanhood#decoding womanhood#likethediner#like the diner

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

What It's Like to Be Transgender and Face Dysphoria and Body Dysmorphia at the Same Time

This piece is part of @allure's coverage of National Eating Disorder Awareness Week

As someone with a fluctuating self-image and a trans person who feels a simultaneous external demand and internal anxiety to continuously communicate my gender, I’ve never felt at peace with my appearance. Sometimes my desire to be seen can be confusing; I barely have a solid grasp on what I look like, especially to other people. How I feel about myself is nearly always about other people.

Understanding myself through the eyes of others provides a blueprint for me to have control over my self-image. In part, I'm hesitant to admit that maybe the feeling that control eludes me is what it means to have body dysmorphia and gender dysphoria concurrently. Maybe these things are in the driver’s seat more days than I am, and that is a reality I fear confronting.

The Origin Story of My Body Image Issues

Both of my parents grew up poor in Jakarta, Indonesia. With a desire to shift the trajectory of the future for them and their children, they found and worked well-paying jobs. They raised my siblings and me in Jakarta, but in contrast to their childhoods, we were financially well-off. To us, food was more than just food — it signified financial safety, a lack of scarcity and hunger. For my parents, my siblings and I were not just children, we were pockets in which they could invest assurance and safety; a second chance to witness childhoods without want.

My parents worried about us ever going hungry, and by eight years old, I was consuming cod-liver oil supplements daily and eating almost nonstop. Physically, I came to embody abundance because, from my parents’ perspective, I should have never gone hungry. But this physicality was also a symbol of shame, because from everyone else’s perspective, I was merely a fat kid. In my consumption of the safety my parents provided, I was losing some of my agency as societal fatphobia affected me. My complex relationship with my body began early; with every look in the mirror, I asked myself, "Am I to be thankful or remorseful for this body?"

Realizing I Had Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Contrary to what I was told by my environment, I felt indifferent about my body fat. It meant very little to me, though I disliked the way it shaped how people treated me. As a preteen, I don’t recall feeling embarrassed about being fat, but I think that’s one of the survival tactics you develop when you’re subject to harassment as a fatter kid in class and at family gatherings.

Though most of my childhood didn’t revolve around my weight, I recall feeling frustrated — even confused — when I had to look at photographs and footage of myself. In my head, I had a very clear image of what I looked like, and yet it was far from what I saw in pictures and videos of myself. Maybe my weight was part of that gap in perception, but it felt deeper and heavier than size. Body weight can change, and I feared that the dissonance between how I saw myself and how I actually appeared would never go away, even if the body weight did. I recognize this now as body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

“The main component of BDD in a person is the primary feeling they are not who they are, having displeasure, and being unable to accept oneself physically,” says Emily S. Rosen, a licensed clinical social worker in New York City, trained in modern psychoanalysis and Gestalt psychotherapy. “Sometimes people see themselves differently than they are; like you see something in yourself that might not be there, but it feels like it’s there.”

To work through BDD, Rosen tells Allure, “I believe that if we had more compassion for ourselves, we would have more compassion for each other.”

I have yet to fully embrace that compassion for myself, but coming out as a trans woman and pursuing a medical transition at age 18 was a huge step for me in reclaiming my body. It was monumental for me to say, “No, I’m not a boy, I’m actually a girl,” because I felt like I was taking back my physical narrative. But I soon found that I was unprepared for the additional set of complexities and questions transitioning brought up.

Understanding Gender Dysphoria

Similar to BDD, gender dysphoria (GD) occurs when there is a disparity between one’s gender and the perception of their gender through societal constructs. Transitioning for me was a way to work with my BDD, but not because I was initially dysphoric about my gender. In college, I recognized my appearance less and less as testosterone gradually increased and affected my development, changing physical aspects such as bone structure, face shape, hairline, body hair, and more. I figured if testosterone drove me to perceive myself as masculine in a debilitating way, the only answer was to undo its effects by going on estrogen.

A few weeks after coming out, I scheduled an appointment with a psychotherapist to obtain my approval letters to undergo hormone replacement therapy (HRT), in which the testosterone in my blood would gradually be substituted with a prescribed dosage of testosterone blockers alongside estrogen. As an Internet kid, it wasn’t hard to surf the Web to prepare myself for the questions psychiatrists would ask me before determining whether or not HRT would be a good fit for me.

Shortly after I got my approval letters diagnosing me with gender identity disorder (GID), I met with Carolyn Wolf-Gould, a family physician who, since 2012, has worked at the Gender Wellness Center in Oneonta, New York, a facility that has worked with over 700 trans patients. During our first physical exam, she felt my throat for what was supposed to be an Adam’s apple. When she didn’t feel anything there, she said, with a promising grin, “Ah, you’re going to be just fine.” Before that moment, I’d never thought to have an opinion about my neck's appearance.

I believe she meant to assure me that an Adam’s apple, or lack thereof, was not something for me to be dysphoric about, but this moment taught me something bigger: There is a mold of what a woman should look like, and it was possible for me to fit that mold. Yes, it was comforting that nothaving an Adam’s apple was one less thing to worry about, but in that moment, I began second-guessing other aspects of my appearance.

After our appointment, I created a routine for myself. To avoid a five-o-clock shadow that I wasn’t even sure was an issue, I began color-correcting my face before applying makeup. I covered myself up with cardigans to assuage the fear that my shoulders were too masculine. I dressed in hyperfeminine clothing because I wanted to minimize the risk of being perceived as anything other a woman.

Because of BDD, I had always had a generally strange perception of myself. When I transitioned, I noted the pressures and expectations of presenting as a woman and eventually developed GD, which gave me an idea about exactly how I wanted to look. I went from wanting to just realistically recognize myself in the mirror to wanting to see myself as a woman, without a doubt.

The Compounding Effects of My Dysmorphia and Dysphoria

Because BDD and GD coexist, I need people in my life to understand the varying capacities of strife they cause me and how the two can compound the effects of each other on a day-to-day basis. Having gender dysphoria has forced me to be more in tune with myself, perhaps too much. When communicating my gender, I am hyper-aware of the way I present myself. Though I wish I didn’t have dysphoria, having some grasp on my appearance lessens the dysmorphia that blurs my perception of self. But on certain days my dysmorphia still gets the better of me, and when I see my reflection, I’m back to a place of confusion. At other times my dysphoria has a strong presence, and the effort to stand in my womanhood feels embarrassing and ineffective.

I don’t need doctors or therapists to validate that I am a girl who has a body, and that my body and gender are never going to be mutually exclusive, be it by my standards or someone else’s. “The number one misunderstanding of gender dysphoria is that it needs a pathological diagnosis of gender identity disorder, or GID, under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM),” Wolf-Gould tells me. “The reality is that many trans people aren’t dysphoric and still need treatment. Then, how do they get cover[ed] in insurance? Thankfully, now there’s a new diagnosis: ‘gender incongruence,’ which means there’s a mismatch without any overlay of depression or upset-ness.”

I have no blueprint or calendar or meteorology report to predict the things that might impact my day. A few weeks ago, on my way home from school, it rained suddenly. On the sidewalk, I walked by a mother twirling her daughter in the rain. In between the patter of raindrops, I heard the clear joy in the girl’s laughter. I felt it ground me, reminding me of when I lived in Indonesia. I loved the way the beach swallowed my body whole. The ocean water was the only thing that understood my body's changes. I could stand still or swim, and know with full certainty that the water would still envelop every inch of me. I want to know how to live like that on land.

Ridding myself of dysmorphia and dysphoria seems unimaginable, and the shame of being truthful about my body image keeps me in silence. Daily, I am working on breaking that remorse, finding reflection not in images, but in stories.

*edits assisted by Rosemary Donahue and the team at @allure*

#Eating disorder awareness week#bdd#gd#body dysmorphia#body dysmorphic disorder#gender dysphoria#dysphoria#lgbtq#lgbt#trans#transgender#allure#allure magazine

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gap Between Glamour and Death for Trans Women of Color

(piece live at them.)

[image description: a mirror selfie of myself]

The year I started transitioning at school, another student walked by me, pointing up and down at what I presume was my outfit.

“Yasss…” she hissed.

There were better ways for her to compliment me, but the rush of being seen and recognized as fabulous only made me sway my hips more, raise a little bit of eyebrow and smirk.

I was addicted to fabulosity. Early in my transition, I would spend hours each day picking out an outfit, and then even more time doing my hair and makeup. I invested in glamour because I felt it made up for the fears that accompany being trans; I had something people could associate me with other than a statistic. I thought, If I can look better than cis women, there’s no room for anyone to pity me as the “brown trans girl.” I believed that by adhering to cisnormative beauty standards, I could access experiences of life and love my transness would potentially take away; so I used beauty as a shield.

But I eventually realized that no matter how much I painted myself to conceal my transness, it wouldn’t change who I am when I go to bed at night. The truth returns with makeup wipes, with untucking, with the bareness of my body. I scroll Instagram and see Laverne Cox’s blonde hair blowing in the wind of a fan. I see Janet Mock in dresses designed by Christian Siriano. I see Geena Rocero in the Philippines posing in a bikini of plumeria leaves. I see beautiful trans women of color like them, all glamorous, fabulous, and certain. And while I am profoundly emboldened by the work of trans women of color who are recognized in our society, I feel I have no option but to be fabulous, rich, and famous in order to be okay with who and where I am.

When I turn to Twitter, I see Naomi Hersi, Nikki Enriquez, and Dejanay Stanton, all trans women of color. Their narratives are all about murder. I read about their tragic deaths and I want to chop off all of my hair; I want to scrub my makeup until my skin is raw; I want to mask and camouflage everything brown, transgender, and woman about me. I step back into my bubble of fear. I braid my hair tight and throw on a T-shirt, a pair of leggings, and a cap before heading out. I make sure to wear enough foundation to cover up any indication that I am trans, but not enough for people to see me as glamorous.

[image description: a mirror selfie of myself]

For trans women of color, representation is a polarizing topic. There are the well-known trans women of color we admire, and there are those we mourn for. It is easy to be inspired to do great things by the former, and it’s easy to see the latter as evidence of the fact that many of us are in constant danger. But what lies between these extremes of fame and death? Do I have to die in order to matter? Do I have to become a celebrity? I’m stuck between feeling like I need to be beautiful in order to be taken seriously, and feeling like I need to be invisible to be safe.

These days, I save glamour for social media. Posing for the camera becomes routine and practiced, imitating the trans women I see on my Instagram feed. Sometimes, I mention my transness in captions as a “quirky” way to classify myself as a fabulous girl who just happens to be trans. Perhaps I’m inadvertently contributing to this representational divide by posturing myself online as somebody whose makeup is always beat, whose fit is always on point. Otherwise, I feel empty-handed with nothing to offer, even though I would be a more tangible person to everybody else who is like me.

Offline, I hide behind my glasses with no eyeliner, and I have fewer fancy outfits to showcase. My day-to-days are spent going to school; I get my offline euphoria walking down the street without anybody staring. This invisibility is also something I have to practice, navigating the fuzzy line between passing as cisgender without being seen as too fabulous. Perhaps this, too, contributes to the polarization of trans women’s stories. After all, staying invisible in public won’t protect those girls who lack the luxury to be invisible from harm.

[image description: a mirror selfie of myself]

Maybe there are other trans women of color like me out there — others who find it difficult to straddle these worlds. There are days I feel so inspired by famous trans women that I want to put on my best look and strut down the street. There are days I am so terrified of my transness that I want to curl up in my bed for ages. But most days, I simply go to school working towards my master’s degree, which is both as boring as it sounds and a massive milestone for a girl like me. Sometimes, I put on winged eyeliner and wear heeled boots to class, and while plenty of people wear eyeliner and heels in New York City, I feel a certain thrill by pushing myself to inhabit that gap between fame and invisibility for the trans community.

I shouldn’t need to center my worth around my appearance or the circumstances of my community. There are girls who aren’t glamorous, girls who are proud to stand out in their beauty, girls who don’t want attention, girls who go to school, girls who work full-time jobs, girls who work four full-time jobs, girls who are broke, girls who are boring, girls who sing, girls who write, girls who show up empty and are still alive.

As we withstand the suffering, we also prosper. Our stories deserve to be told.

---

*edits assisted by Tyler Ford and the team at @them*

#them#conde nast#dw#trans#transgender#lgbtq#them.#them.us#naomi hersi#nikki enriquez#dejanay stanton#twoc#passing privilege#trans is beautiful#girlslikeus#girls like us

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thrift Shopping Helps Me Explore My Trans Womanhood

My first article for #them! Read here: https://www.them.us/story/thrift-shopping-trans-womanhood

#them#conde nast#them.#transgender#trans#twoc#thrift#thrifting#thrift shopping#trini#yellow power ranger#thuy trang

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consistently Inconsistent: A Struggle for Interpersonal Relationships

[image description: an old photograph of myself at 2 years old]

To the birds who leave the Arctic tundra for Louisiana and build the same nests, to the kids who spend the school week at dad’s and the weekend at mom’s and daydream during the car rides to and from their place of stay that night, to the undocumented cooks at SoHo whose food leaves intergenerational love on the tongues of those whose homes are across the globe, sitting beside the regulars who live just two floors above the eatery, to the kindergarten teachers in Portland whose students come and go even when their lesson plan algorithms never change, I ask: How do you find consistency in inconsistency? What is the role of joy in consistent inconsistencies?

The earliest I can recall when inconsistency became a regularity is at six years old, living in Jakarta. By the demand of my parents, I stopped by all of my friends’ apartments in our complex to say goodbye without having an answer for “Why? Where are you going?” It felt like when I would pop by in the evenings to play, without an inkling as to what we would do that day—just an offer of our hands, empty with hunger. Except, this time, my arrival was not on my terms, and the opportunity for another day of muddy shoes and scraped elbows on small bodies that felt the world was theirs was not guaranteed. I don’t remember my parents telling me what was happening, but I could only be curious for so long until I acted on autopilot. My suitcases were packed, I shook hands with the elders I saw on a daily basis, said “Thank you for everything”, and got inside the car. I didn’t question why we were at an airport. I didn’t question where my dad was until he met us at our new house.

It was late at night when we arrived to Bali—it turns out my dad moved locations for work— and the crickets in the front porch bushes took over any sort of thought I could have formulated. The ceilings were high, the walls were a grayish raspberry pink, and the warm lights made higher parts of the walls a silent crimson. But everything was dim—the house, the faces of the friends I left behind, my dad’s serene smile when he welcomed us, the sense of belonging to a newfound space. Still, I never questioned any of this. The friends I made then, whose names I shouted daily, are nameless to me now. I made great friends in Bali, though now my memory of their faces are intangible. The drive from our house to school was one of my favorites, and I can barely put an image to that nowadays.

Some moments remain vividly. My dad woke me up every school day and carried me down the stairs on his back, an intimate routine before getting ready for school. These were the same stairs I would eventually run up when he scolded me for putting on makeup, in which his gender policing also became an intimate routine in my teenage years. These were a series of consistently inconsistent moments, feeling the most restricted by the first man I knew to make me feel the most free.

[image description: an old photograph of me and my mother]

After a year we moved again. I remember saying bye to a few friends. They are still nameless and faceless. Moving to Balikpapan required us to tweak our dialect in order to submerge into the neighborhood seamlessly. My siblings and I never talked about how this made us feel, but it was an unspoken truth that this brought out discomforts, considering the conversations we held (and still hold) with each other at home never changed regardless of location. Adaptability became a strong foundation to our survivability as a family that moved frequently. But in order to adapt, there is a necessity to let go of and leave spaces, which also became part of my foundation. Moving became harder because I grew stronger feelings for the people who were not required to love me but did anyway. I never had words for this then, but if I did, I would seal their names in some empty memory space in reservations of rekindling one day.

After third grade, we left Indonesia altogether and moved to Elmhurst, in Queens, New York, where I was put straight into fifth grade because of age-grade level placement misalignments. It wasn’t easy, but I adapted. I said bye to my friends, but I didn’t think to keep in touch with any of them. What would I tell them now? That I’m trans? That in order to revitalize a young friendship, it starts with the basis and explanation of my gender transition? This would be too much to start, let alone to maintain. My parents showed me silent simplicity, but simple and silence came with a complexity of emotional repression, and a necessity to let go of the people whom I cared for, and them for me.

We moved upstate for 7th grade. Up until college, I left friendships and friend groups after a year, only to build one over again with someone different. In high school, I spent school weeknights at play rehearsals and the weekends alone in my room, day dreaming on the car rides to and from school, wondering what home really meant for someone whose ground was momentously inconsistent. Some of my friends lived five minutes away, some of them all the way in Jakarta, or Bali, or Balikpapan, or Queens. My behaviors never changed, but there was always a reason to move somewhere else despite my stability. My maintenance of interpersonal relationships is a space of struggle because my relational independence is a habituated circumstance out of innocent yet unhealthy patterns, not a preference or a choice. The consistency in all of this is my unknowing of the ability for patterns to be unbeautiful, and the unanswered questions stick with and shape me into a bigger question that is: How do I find consistent happiness when my carving is nothing short of uncertainty?

[image description: an old photograph of my 5th birthday party]

The birds leave the Arctic tundra for Louisiana to build the same nests because sometimes migration is vital to survival. My family flew across the globe to build the same future on a different soil because new circumstances are an important risk for potentially better development. Kids of divorced parents go back and forth because an unsuccessful marriage does not constitute a dysfunctional family, and although this is still a space of struggle, an unsteady home does not constitute my undeserving to belong somewhere. Undocumented chefs cook for people from all walks of life because it takes ironic jobs to recoup family members who live across the globe to a country that has every power to dismiss them. My family is mobile not because of a preference, but because the in-betweens of a start and a goal is a trajectory that can look as messy as it needs to be. Teachers utilize the same lesson plans even if the attendance of their students are temporary because they understand there are outside circumstances that will drive people elsewhere.

I have to understand that there are outside circumstances that drove me here. But out of habit, here is not permanent, and unpacking this is where for once, I feel stuck.

A few months ago, while I was home from school for winter break, I told my dad, “Everyone in my life is temporary, even when I don’t want them to be. Do you know how bad moving all the time messed me up?”

He remained still as I packed my bags for school, readying to return to where the friends I love have become the first destination I now refuse to let go of easily. Perhaps, you could say this personal momentum is moving. And it is, but I’m bringing the people I love along with me, always.

#transgender#trans#trans is beautiful#girls like us#girlslikeus#trans relationship#transgender relationship#diaspora#moving#relationships#interpersonal relationships#lgbtq#twoc

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

- a vulnerable january

Hi, everyone!

In the midst of my last semester at undergrad, I wrote this small piece. I am currently enrolled in my final classes, assistant stage managing a production of Barefoot in the Park, sharpening up for the 2018 national College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational (CUPSI) in Philadelphia as a member of the poetry slam team, and gearing up to pursue a Master’s degree.

I have so many things to write about! But when it’s mid-winter and you are wrapped up in your blanket on your twin-sized bed, hungry for something warmer (like a companion), your mind wanders to places too frigid (like vulnerability).

With that being said, it is sometimes too difficult to find words when the dictionary fails you. Or when goodness is so wordless it deserves to be left unwritten. My poetry is a default language. Here is my piece. Cheers! xo 💛

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

21st Birthday

I turned 21 December 5th!

Rather than a long post about the first full year of my twenties, I decided to write a short poem about the pivotal moments while twenty years old. From sexual relations I’ve regretted, to discovering a great book, to spilling my life for hours onto empty pages at coffee shops, to having difficult conversations with people I love, to crushes, I give you my all.

Cheers! xx 💛 dw

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I'm ftm but you're blog inspired me to come out and ask for what I want; even if you are the opposite of me. You are really beautiful.

Thank you for making my day, I’m sending you strength, patience, and power as you move forward to a better you ♥ Be kind to yourself, don’t forget that regardless of progress, where you are is always good enough! xx dw

1 note

·

View note

Text

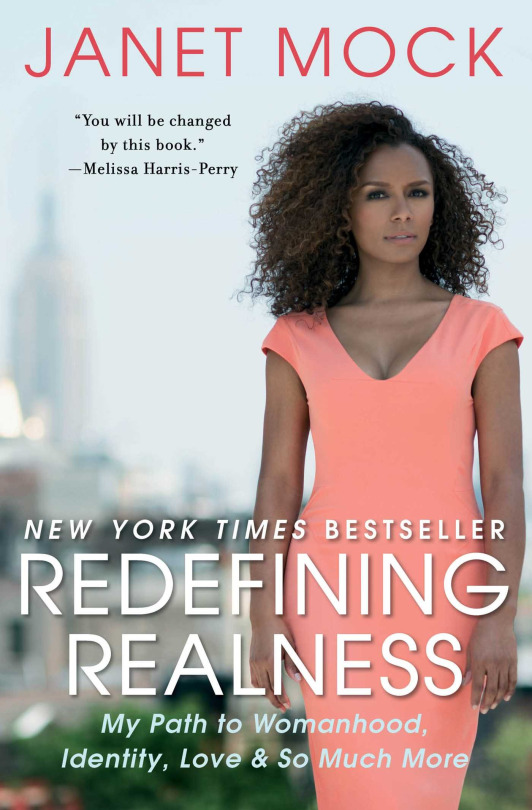

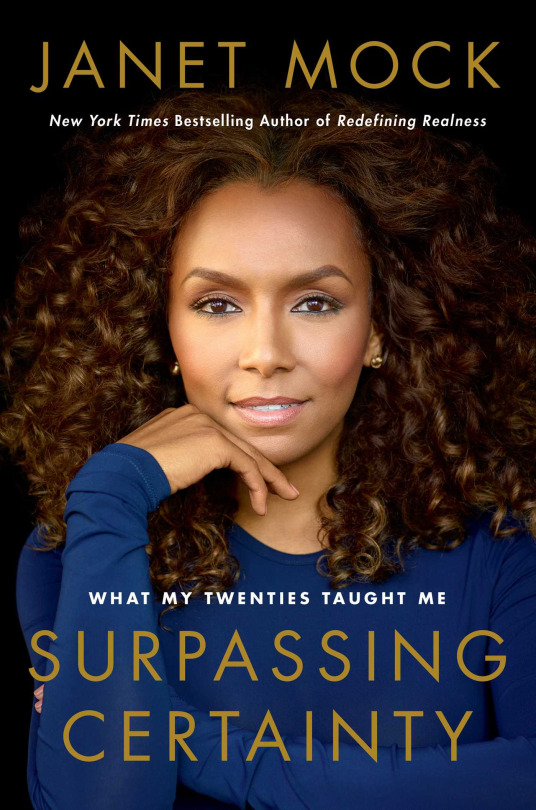

“Surpassing Certainty” by Janet Mock

On the cover of Redefining Realness, Janet Mock bares her presence with what looks like a blurred city far beyond her. The ambiguity of what place she’s in front of parallels with her heavy history that she once left behind out of circumstance, driven by heavier ambitions as a young person with multiplicities. She reveals that the cities of her past are Honolulu, Oakland, and Dallas. On the surface of the memoir, she stands at a far enough distance from the background to convey clear separation from what is behind her, yet also stands at close enough distance from the reader’s eyes for her to be detailed, but still untouchable. I can see her curls, free, vivacious, and parted to the side. I can see her silhouette clearly in the tight, short sleeve, V-neck, midi dress in her favorite color, coral, in which she said on Heben Nigatu and Tracy Clayton’s podcast, Another Round, “It’s a color that I keep returning to […] It’s a color that keeps following me […] but it also just looks good!” Her literal position between her background and the reader’s eyes reflects deeply on the ways in which her experiences are familiar, yet distant. She acknowledged this on Oprah Winfrey Network’s SuperSoul Sessions, by tearfully saying, “Just because I clicked my heels and I made it out of Oz, doesn’t mean everyone can.” In the space of otherness, you can still feel othered.

On the cover of Surpassing Certainty: What My Twenties Taught Me, there is no background—only a black backdrop of what looks like the photograph was taken in a studio, indoors and more intimate. Janet is up close and personal, and that shows in the stories throughout the book. Her first memoir, like the cover itself, was expansive and full of depth. This time, the sole focus is Janet, in every multitude of who she is. I love that she wears a long sleeve, crew neck dress—it’s more concealing. Ironic that although she is significantly closer in the picture, she is less revealing. It spoke to me as the power of choosing when to camouflage and when to uncover yourself. She introduces the book with a one-night stand story, where in the midst of her physical nakedness with a stranger, she wore an armor that shielded her from undressing her truth—the complex relationship between privacy and intimacy, and how they are not always as mutually exclusive as we might think. In the picture, her curls are more defined and gentle, parted in the middle. She still wears her favorite color, but this time, on her cheeks, where the coral blush is placed just right to ignite her immaculate cheekbones. Intentional beauty is a kind of beauty I knew all too well—a beauty that has been redefined and refined in order to be granted access to opportunities. There is a relationship between the comfort of hegemonic identities and the ways marginalized folks strategically convey beauty to satisfy those comforts. This is evident in how you wear your hair to an interview (policing of hair textures), how “right” your skin tone is (colorism), and how well your beauty can chameleon itself for whiteness. These experiences Janet speaks of in Surpassing Certainty are beyond her transness. What makes trans women of color’s stories different from “popular” and well-listened-to trans narratives is that their race is involved. In this book, she touches on the roles of her race, disclosure of transness, womanhood, and how they intersect.

ESSENCE’s Cori Murray and Charli Penn from the podcast Yes, Girl! sat down with Janet, where they asked her, “Do you ever grapple with being an advocate?” She responded with: “It’s part of the work that I do. Though I center myself and my experiences […] I can’t forget that so many people don’t know about all these other women who have not been given the same privileges and access that I have been given to be able to live, to survive, and ultimately to thrive and live my dreams.”

My 20th birthday was pivotal in that it marked the end of my teenage years, years that I never knew I was able to give closure to or move on from. Especially the year of being nineteen, which was my expedition of disclosure, sex, intimacy, and its relationships with each other. I—someone who recently begun her twenties whose experiences were also of being a mixed trans girl from the islands, navigating transness in the context of stealth and intentional suppression— never expected to have a kind of resource like Surpassing Certainty, which covered the years from before Janet was even twenty, up until her thirtieth birthday.

I thought Redefining Realness spoke to me in ways nobody ever has. Reading it three times, I felt recognized, cared for, and prioritized. But in telling her own story in Surpassing Certainty, Janet allowed me to see myself. By the end of the book, I had an awakening that in the midst of relationships, job opportunities, heartbreak, spaces, it was beyond crucial that I choose myself over all of these. Always. Oftentimes I catch myself in this tug-of-war of “Who would stand beside you—in public—and call you theirs?” (37) and “But you can’t escape your truth. It follows you. No matter how far you travel, how good you feel with it at a distance, it lingers and sticks to you” (33), and I resort to myself. Janet described the comfort of lonesome in a way I have not been able to articulate— “Perhaps no one would ever know me quite as well” (124).

Choosing myself is healing; resorting to myself by default is lonesome. As a person who grapples with emotional unavailability, I submitted to men who knew I’m trans by only fucking them, and romantically getting involved with men whom I did not disclose my transness to. Spaces in between came with an expensive price of emotional labor, and I couldn’t afford that. My twenties is about being stingy and holding people on a higher level of accountability. When Phoebe Robinson of Sooo Many White Guys interviewed Janet, she asked “Out of all the important experiences that happened in your twenties, what’s one piece of advice that you would give to someone?” Janet responded with: “Not everyone is deserving of you, of your body, of your story, of your time […] Don’t spend it. Budget that shit!”

I started to refuse crumbs to satisfy my hunger for desire. When James texted to see me at midnight, I knew the choreography by heart. I’d see him, he’d be inebriated beyond control. He’d make small talk bullshit before giving me a taste of his night’s bar tab. We’d slip out of our clothes and into my bed, and he’d slip into my body before slipping his way out of my room. I was exhausted of this kind of pleasure, the one-way-narrow-road kind of pleasure, so I texted him back, “No can do, tonight.”

He texted me back with, “Ugh.”

He didn’t even fight for it. He never had to, so why start?

It felt good to know he was upset. It was also so foreign. He could fuck anyone, I thought, and he chose you. Who do you think you are? Why would you turn down a guy who will taste the secrecies of your skin when no one else will?

I thought again.

…Because I’m everything, and he does not deserve even the most sun-kissed parts of my flesh.

A few weeks later, I met a 22 year old guy named Sam at a late night party event in a vintage boutique that hosted his band’s album debut. He sang the harmonies with one hand patting a cajón he sat on, wearing a white Manchester United jersey that looked like it was his favorite shirt to wear—stained and rugged. With cheap red wine and a few ice cubes in my red cup, I unapologetically let his eye contact mutualize mine while I stood in the crowd, which led us to introducing ourselves to each other afterwards. He told me about a rooftop party he attended in Chelsea for his job at an entertainment company, where well-known actors like Lucy Liu and Zoey Deutch surrounded him, boosting his ego. I went home, tired, and swiped on Tinder. His profile was the first to show up, and I swiped right. Instant match.

“Tell Lucy Liu I say hello, will ya?” I teased.

Within the next day, we progressed onto texting.

“Come visit me in the city,” he said. I remembered then that this game of let’s see how long I can pull men into my life before I push them away to avoid disclosure, and possibly, rejection, couldn’t keep on going. That night, I told him about my transness.

Taken aback and curious, he responded respectfully, and proceeded to thank me for being forthcoming. When I shared my relief of his reaction, he messaged me back with an answer that caught me off guard, revealing that he had much more to learn than what I initially thought he already knew.

“Hahaha. You didn’t tell me you were the guy that killed my father. Just told me you’re a guy, that’s all.”

“Mmmm, not quite. I’m not a guy, but you have Google to figure it out yourself. Also, your dad isn’t even dead.”

This was my point of exhaustion and refusal to be anybody’s source of research—especially people whom I catch myself looking for validation in.

Just like Janet in Surpassing Certainty, I was stuck in the pattern of not allowing myself to deserve the best; “I embraced the sweet delusion that ignited all affairs: This time, it will be different” (77). But it never was. It was the same shit every single time; men who prioritize their confusions over my own personhood, men who want me in the darkest of the unseen, men who do not know how to love and respect me.

It is in friendships that I find myself the most powerful, and Janet and Lela’s is one I truly admired. Lela’s reaction to Janet telling her truth was the ideal reaction I never knew I wanted.

“I felt lucky you told me”, Lela said. “But no one should ever feel obligated to know, you know? It’s your story to tell.” (148)

I am so in awe of Janet’s generosity, willingness to give, and ultimately, welcome us into her story. So many of my parallel experiences with hers I dealt with alone, pushing me to a space of singularity. But for her to share them bare, and for me to even see just a spec of a dust of myself in that story, I was pulled out of that deepness. I especially found commanding power in the way Janet and Troy’s argument in the car (while she waited for her train to come) ended.

“‘I love you’, he said.

‘Me, too.’” (208)

There is a potential pronoun antecedent slip here, and I ruminate over what Janet meant by “Me, too.” In a quick glance, I figured that was her way of saying “I love you, too,” but after rereading that part, deep down I wonder if this was a turning point of Janet’s priorities that allowed herself to say “I love me, too.”

Janet’s work makes me dig a little deeper, allowing me to heal numbed wounds I’ve forgotten were even there. Desire, hunger, and persistence are universal experiences that aren’t exclusive to trans women of color in their twenties. But the roots in which trans women of color’s desires, hunger, and persistence are grounded in are different, with respect to race, gender, time, histories, and traumas. Even in our shared communities, our layered experiences still have room for divergence—and that’s the importance of trans narratives; they aren’t monolithic. My chapter one looks different from Janet’s chapter one, and that is a truth to be untouched and unquestioned. Alike of the women in Club Nu, “We were marked by life, decisions, and mistakes” (29). We still are.

I have so much love for trans women of color, even if our community is dying more than I want to admit. I believe in the strength of heart and the selflessness of sisterhood. Janet, you have given us oceans in a time of drought. I’ve surpassed certainty that I will always love you for that.

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

This blog is so fantastic!!!

Thank you! Appreciate that

1 note

·

View note

Note

You're beautiful and I wish you the best

Thank you so much! Wishing you the best as well

2 notes

·

View notes