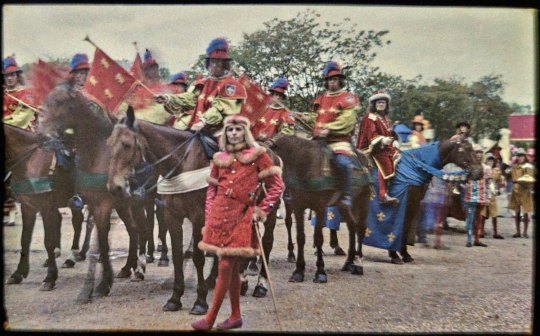

#medieval parade

Text

Robert Daché (Dasché) :: 'Cortège historique', 1931. Lumière autochrome with original retouching in color. © Robert Dasché. | src Daniel Blau

view on wordPress

#robert dache#Autochrome#robert dasche#early color#parade#Lumière Autochrome#historic parade#cortege historique#autokrom#early colour#autochrom#medieval parade#autochrome#1930s#additive color screen plate

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

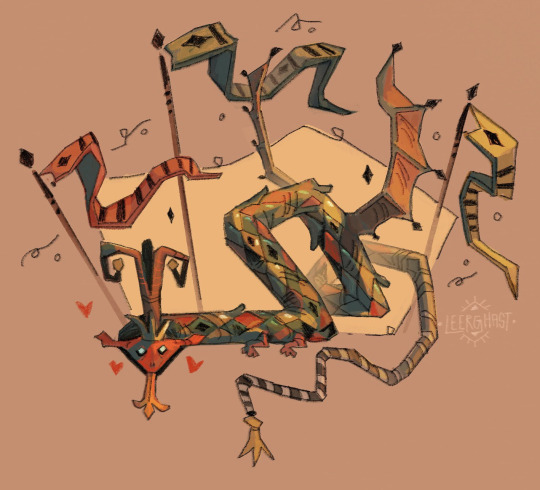

Writhing, King of wyrms

(she/her)

Writhing is the king and mother of wyrms. She is an important character from my story.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

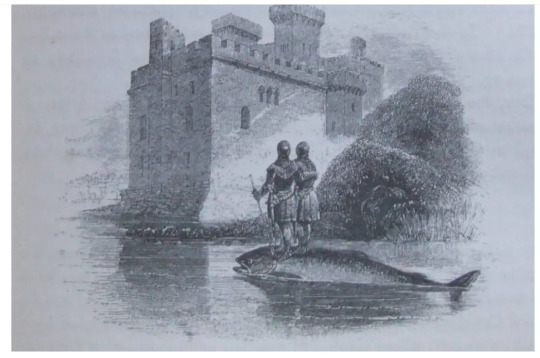

Sir Kay, Seneschal of King Arthur's Court, Harold J. Herman / Illustration from the Mabinogion / The Quest for Olwen, trans. Gwyn Thomas and Kevin Crossley-Holland / The Story of Merlin, trans. Rupert T. Pickens / Illustration from The Quest for Olwen, Margaret Jones / Wace's Roman de Brut, trans. Eugene Mason / The Mabinogion, trans. Lady Charlotte Guest

a collection of sir kay and sir bedivere: companions/lovers/worse, for @queer-ragnelle's may day parade

#fellas is it gay to forever be linked to your companion throughout texts and time#them being the first of arthur's knights ohhh im so emo about them.... arthuriana's most eternal couple#you guys should read that article i linked if ur interested in how kay changes over time btw!! it's really good#bedivere#sir bedivere#kay#sir kay#culhwch and olwen#vulgate cycle#mabinogion#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian literature#medieval literature#knights of the round table#kay x bedivere#bedikay#i think ive seen people using that tag?#may day parade#I know this isn’t art so maybe it doesn’t count but the formatting alone should count as an art this was nightmarish to create#kay tag

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

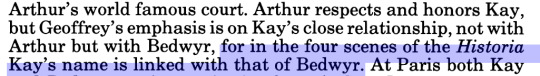

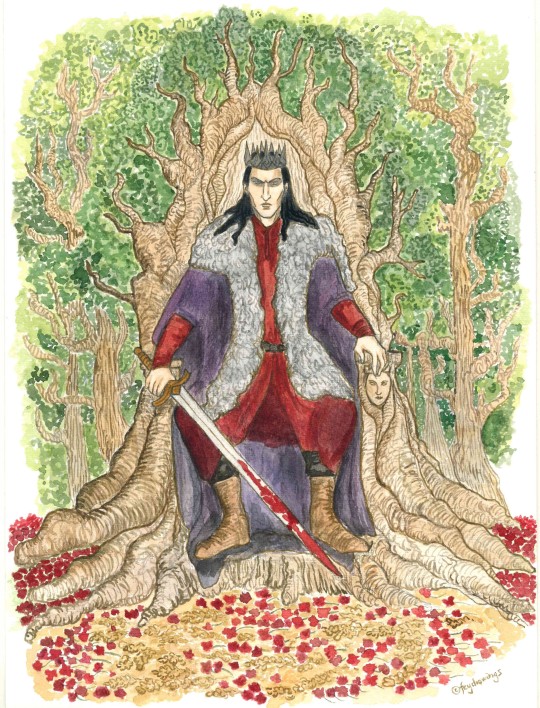

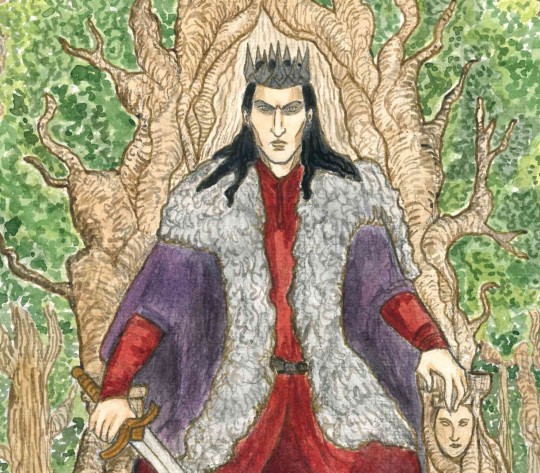

May King Mordred for the prompt Morbid Month of May of @queer-ragnelle 's May Day Parade 2024 !

Mordred as the May King: not a symbol of rebirth and of life, but of death and destruction. The rise of the new king comes at the expense of the old king, the old year has to die to allow to the new year to come, the corn grows only to fall under the scythe of the reaper, the flowers blossom only to die. And like corn spikes, countless men fell in the war between Arthur and Mordred.

[please click on the picture for a better resolution. unfortunately tumblr likes to destroy the quality of uploaded drawings]

#may day parade#may day parade 2024#may day 2024#arthuriana#arthurian legend#arthurian legends#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#medieval literature#sir mordred#mordred#the may king#watercolor#*mine: art

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Henry of Lancaster’s Expedition to Aquitaine

Henry of Lancaster’s Expedition to Aquitaine, 1345-1346: Military Service and Professionalism in the Hundred Years War serves as a detailed study of the army and campaign of the Earl of Derby in Aquitaine, a prelude to the famous Crécy campaign of King Edward III which was to follow. It is the fame of Edward’s campaign, Gribit argues, that has caused Lancaster’s Aquitaine campaign to be overlooked by historians. It is this lacuna which Gribit seeks to fill with this book.

This book is organized in nine chapters, which are divided into three sections with an additional introduction and conclusion. Part I, which consists of chapters one through four, is entitled “Henry of Lancaster and the English Army: Soldiers, Payment and Recruitment”, and provides a detailed account of the army serving under Henry of Lancaster. Chapter one contextualizes the situation which had been brewing between France and England, tracing the tensions back to the acquisition of Aquitaine by Henry II in the mid 12th century. From this beginning date, the author briefly outlines the history of violence between England and France up to the beginning of Edward’s war. Gribit then provides a detailed biographical account of Henry of Lancaster’s life up to the events of the Aquitaine campaign.

Chapter two examines the composition of the army led by Henry in Aquitaine. The indenture entered into by Henry and Edward stipulated that Henry’s force should be 2,000 men: 500 men-at-arms, 500 Welsh infantry, 500 mounted archers, and 500 unmounted archers. However, Gribit calls into question the traditional historical view of armies as being composed of either infantry or cavalry, stating that this distinction does not hold true for the method of English warfare in the fourteenth century. As such, he sets out to define each of these troop types, as well as examining the composition of Henry’s army from the point of view of troop type. Gribit also examines military rank and social status. The authors argues that the archers should be understood as comprising two different social strata, i.e. those who were mounted and those who served on foot. Archers are divided into mounted archers and unmounted archers, with it being noted that mounted archers seem to represent a distinct social class unto themselves. He also argues that mounted archers did not join battle on horseback, but rather used their mounts for transportation and the chevauchée. Finally, the Welsh infantry are described as either bowmen or spearmen, and as the lowest paid troops in an Edwardian army, represent the lowest social class.

Chapter three focuses on the logistics of raising an army. Gribit identifies two primary methods of recruitment used by the English crown in the fourteenth century: indenture and the commission of array. Indentures are described as the most useful form of recruitment when the King and his Wardrobe are not present. The indenture system allowed captains such as Henry of Lancaster to raise and administer an army as specified by the terms of the indenture to fight independently of the King. Gribit identifies this system as pivotal to the multi-front war that Edward waged in France. He draws contrasts between the indenture model and the raising of troops through a commission of array, which was the “traditional” method of raising troops. This method uses local officials to raise a large number of infantry from their area of influence, however Grubit states this method was rarely used for bringing troops to France after 1369. The raising of personal retinues and pardons as recruitment tools are also discussed before tables for the composition of Lancaster’s army are given.

The fourth chapter, and final chapter of section one, considers financial administration. In particular, Grubit seeks to reconstruct a schedule of payments and trace the path money took from the King’s coffers to the pockets of the soldiers. Certain benefits of service are examined, such as the regard, an extra payment which was given to captains of men-at-arms, and horse restoration. The particular role of the exchequer in accounting for the military is also considered.

Part II of this book is entitled “The English Expedition to Aquitaine, 1345-46.” It contains chapters five and six, and provides a detailed, chronological account of Henry of Lancaster’s two campaigns in Aquitaine in 1345 and 1346 respectively.

Chapter five focuses on the first campaign of 1345. The account begins with the arrival of Henry’s army at Bordeaux on the 9th of August, 1345. Gribit follows Henry’s movements in detail, paying particular attention to the capture of Bergerac and the battle of Auberoche. The campaign (and the chapter) ends with the onset of winter, which Henry spends in La Réole.

The sixth chapter, which examines the second campaign of 1346, begins with the siege of Aiguillon. After the siege, Lancaster embarked upon a lengthy chevauchée which would take him as far as Poitiers before returning to La Réole.

Part III consists of chapters seven, eight, and nine, and is entitled “Military Service and the Earl’s Retinue for War.” In this section, Gribit provides a detailed analysis of Lancaster’s army in 1345, as well as a general consideration of military professionalism in the fourteenth century.

Chapter seven focuses on the formation and structure of Lancaster’s 1345 retinue. Lancaster’s retinue represents the largest known military retinue from the first half of the fourteenth century, and is also exceptional in that the names of every man who served in the unit are known. Gribit begins his consideration of Lancaster’s retinue with an examination of the knights, retainers, and esquires who served in Aquitaine, and the men who served under them. He follows this with a detailed discussion on Lancaster’s knights banneret, and then the royal knights and valets Lancaster brought with him. Gribit then examines the Aquitanian knights who served under Lancaster, and finally lower status archers and attendants who accompanied the army.

Chapter eight seeks to analyze the cohesion and stability of Lancaster’s Aquitanian force. The author states that these factors were fundamental to turning Lancaster’s army into the formidable, effective fighting force that it was. In an attempt to understand the continuity of service provided by the men fighting under Lancaster, Grubit turns to an analysis by Kenneth Fowler, however Grubit disagrees with many of his findings. While Fowler argues that only a small minority of men who served with Lancaster in Aquitaine had served with him in the past, Grubit successfully argues that in fact a large majority of the men present with Lancaster in 1345 had served with him before. Some had been fighting alongside Lancaster since his service in Scotland in 1336. Grubit goes on to examine the effects camaraderie, kinship and marriage ties, and feudal obligations had on the stability of Lancaster’s force.

The ninth and final chapter of this book concerns broader questions of military careers and patterns of service. Grubit seeks to answer these questions through the service of important men who served under Lancaster in Aquitaine. In particular, Grubit examines the military histories of the many high ranking men who fought with Lancaster, and traced the number of campaigns they had served in up to 1345, the number of captains they had served under, and the earliest known date from which they had been campaigning. Grubit set his parameters for military professionalism as having served in four campaigns, and found that approximately 25% of the knights under Lancaster had met this criterion by 1345. After 1345, approximately two-thirds of Lancaster’s men would eventually serve in four or more campaigns. Grubit therefore concludes that a majority of Lancaster’s men were of a status which he considers professional.

The main body if the text is followed by a brief conclusion, an appendix which includes an transcription and translation of Lancaster’s indenture, another appendix which catalogs the men in Lancaster’s retinue, and finally a bibliography and index. This work relies very heavily upon primary documents, particularly Lancaster’s muster rolls and Edward’s exchequer rolls. A substantial body of English and French language scholarship is also referenced.

Grubit provides an intriguing analysis of an army which is generally overshadowed in modern scholarship by the more famous escapades of Edward III. His examinations are thorough and incredibly informative, however the order of the three parts of the book is somewhat confusing. Separating the two discussions on the composition of Lancaster’s army with an account of the Aquitaine campaigns was an odd choice, and the account may have been better placed at either the beginning or end of the work. Despite this modest critique, the book is a valuable work and should be enjoyed by professional historians and well read enthusiasts alike.

#book review#review#medieval#middle ages#hundred years war#henry of lancaster's expedition to aquitaine#parade#history

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the curse of doing historical research for art is that you’ll find stuff that looks sick as hell but from entirely the wrong time period/purpose. may god forgive me but i’m going to take Artistic Liberties

#on a related note i have a basic understanding of medieval armor now#and all the fancy embellished plate armor was used either for tournaments or parades#or by renaissance era mercenaries and not actual knights#idk if this is common knowledge or not but i didn't know#like they didn't really even have plate armor for the crusades or anything it was mostly mail

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man I went to a rad little medieval festival and it really hammered home how much of an awful fucking salesperson I am but it was very nice hearing the knights in full plate walkin around

#just not cut out for merchantry I'm afraid 😔#am absolutely cut out for hearing dudes in plate armor rattling around though#also like this is unrelated but it was rad seeing so many openly queer folk there dude#like shit is Alberta secretly like the Queer Capital of Canada or something like wtf#saw more trans people at that medieval fest than the last pride parade I went to it was wild#hell yeah dude#Pun's text Posts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image of A Yōkai Parade aka The Night Parade of One Hundred Demons (Hyakki Yagyō) is a thousand-plus-year-old Japanese folkloric tradition, in which a series of demons parades — or explodes — into the ordinary human world which is illustrated here by Yuko Shimizu for "Japanese Tales" (2018) a book of medieval Japanese folk tales, translated by Royall Tyler and bound by The Folio Society.

#yuko shimizu#medieval japanese folk tales#medieval japan#medieval japanese folk lore#royall tyler#the folio society#spirits#yōkai#yōkai parade#hyakki yagyō#the night parade of one hundred demons#japanese demons#japanese demon#night parade#100 demons#japanese ghosts#japanese ghost#kasa-obake#karakasa-kozō#umbrella ghost#one legged umbrella spirit

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

FIRA DE L'AIXADA-ART-PINTURA-MANRESA-PARADES-MERCAT MEDIEVAL-PERSONATGES-MERCATS-CATALUNYA-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS por Ernest Descals

Por Flickr:

FIRA DE L'AIXADA-ART-PINTURA-MANRESA-PARADES-MERCAT MEDIEVAL-PERSONATGES-MERCATS-CATALUNYA-PINTOR-ERNEST DESCALS- Personajes en el MERCAT MEDIEVAL de la FIRA DE L'AIXADA de MANRESA, las calles del Barri Antic de la ciudad se llenan de paradas y pequeñas tiendas en los que exponer y vender artículos relacionados con las costumbres de la Edad Media, en esta escena el vendedor nos muestra su atuendo con tintes medievales. Pintura del artista pintor Ernest Descals sobre papel de 50 x 70 centímetros, pintando el aroma histórico y a sus protagonistas.

#PERSONATGES#MERCAT MEDIEVAL#FIRA DE L'AIXADA#MANRESA#BARCELONA#CATALUNYA#CATALONIA#CATALUÑA#MEDIEVALES#MERCADO MEDIEVAL#PERSONAJES#ESCENAS#PARADES#TIENDAS#BOTIGUES#ATAUENDOS#MERCADOS MEDIEVALES#HISTORIA#HISTORY#RECREACION HISTORICA#BARRI ANTIC#VESTIMENTAS#ART#ARTE#ARTWORK#CHARACTERS#PLASTICA#FINE ART#PINTAR#PINTANDO

0 notes

Text

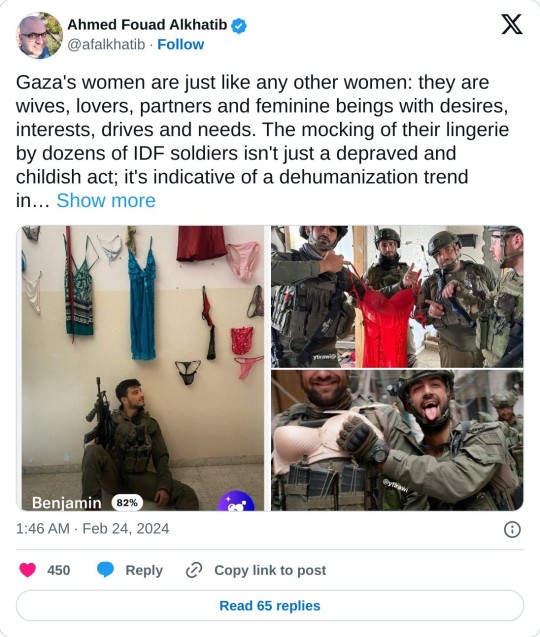

Gaza's women are just like any other women: they are wives, lovers, partners and feminine beings with desires, interests, drives and needs. The mocking of their lingerie by dozens of IDF soldiers isn't just a depraved and childish act; it's indicative of a dehumanization trend in which Palestinian women are viewed as entirely alien and otherized - that the presence of lingerie in their bedroom drawers is so shockingly surprising & unexpected, it is worth playing with and showing off as battlefield souvenir. I remember vividly how widespread lingerie stores were throughout Gaza City and how they were such a casual thing. In fact, I remember numerous instances of seemingly religious men with beards and the Quran playing in the background having or operating underwear and lingerie stores and stands, with their wives or female salesladies even helping them with customers.

These images by IDF troops will have long lasting consequences and will undermine de-escalation and de-radicalization efforts, particularly in a conservative society that views female-related spaces, items and topics as particularly sensitive and private/sacred. This isn't about worn out soldiers blowing off steam during battle; it is a sick lack of discipline & lackluster standards & operational security protocols. These images are deeply disrespectful and offensive and further alienate a civilian population that is paying the price for circumstances over which it has no control.

A Revolutionary Feminist Hip Hop collective released this diss track to the IDF. Inspired by the fierce lioness dignity of PFLP women commanders who have had their underwear publicly displayed. The IDF pigs have been hanging the lingerie of Marxist-Leninist women from the PFLP and DFLP to distance them from their Islamic comrades. Women from the secular leftist revolutionary organizations of Palestine have had their underwear especially targeted. The IOF had worked very hard to "otherize" Gaza as medieval, playing down Marxist-Leninists like PFLP who showed solidarity with Heather Heyer and BLM. They want to distance Gaza from western leftists. But women Marxists who dress like western women have their underwear paraded by IOF.

Yes it is mortifying for Marxist-Leninist PFLP commanders like Shireen Said to be waging guerilla war in the ruins of your homeland. While IOF pigs taunt that they can taste your juices on your stolen underwear. But she fights on with more determination in spite of it all. They can't take away her revolutionary dignity. And even if her panties are something very private, personal and intimate to the proud Marxist commander. It has been the IDF chauvinist pigs who have been more shamed before the world by their behavior.

Shireen Said's brave, dignified, courageous response to the IDF's attempt to humiliate her with her stolen panties, was turned into this hip hop anthem.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Weapons (3): Staffs, Spears and Polearms

Staffs

The staff is inexpensive and in the hand of a skilled fighter - deadly.

Particularly useful for entertaining fight scene, or for spontaneous fights.

A seasoned fighter can fight with a broomstick or garden hoe.

Useful for petite heroine: much lighter, long enough to fight at a distance so that he can't tackle or grapple

Spears

In most period, spears were the most common weapon for warfare

spears are cheaper than swords (better for large armies&peasants)

Spears can be tipped wth metal, stone, or anything at hand (bone, glass shards), or simply have one end sharpened to a point.

The Throwing Spear

An army would throw lots of spear at the enemy to do as much damage as possible before closing in

Each soldier may hold multiple throwing spears

The 'atatl' is used for loading the spear on the shoulder and catapulating it forward. This sllows women to hurl a spear with as much strength as a man.

Some spears are designed so their tips break on impact to prevent re-use.

Throwing spears are fairly lightweight. It is sometimes called 'javelin'.

The Thrusting Spear

The main weapon for peasants pressed into military service

Very long, often made from farming implement

The first row of soldiers kneels with spears low in hand. The second row kneels with spear at hip height. The third row stands with spears at waist height. The fouth holds the spears at shoulder hieight and the fith holds them above.

The thrusting spear is sometimes called 'lance'. If it's very long, it's called a 'pike'.

A warrior can hold a spear in the right and a shield in the left.

Polearms

Polearms are thrusting spears with cleverly designed, large heads which can stab, cut, hook, twist, cleave, push or pull.

Can be used as lances or as staffs

They serve best at a distance (preventing a sword-armed fighter), but can use them close-up as well. Some are even designed to pry open plate armour.

Can add authenticity to a medieval fight scene.

Poleaxe

spear with a tip for thrusting combined with an axe-blade for cleaving.

Billhook

Originally an agricultural tool, a hook-shaped blade for clearing brush.

Billhook has a long handle, a long sharp spike as a tip, and a pronounced hook.blade which serves to pull and cut the enemy's legs and ankles.

Halerd

Axe-blade on one side and a hook on the other

Developed to repel horses and to stop swordsmen getting close.

It became a ceremonial weapon, sometimes worn by guardsmen on parade

Blunders to Avoid

Medieval battles where every soldier fights with a sword

Soldier carrying polearms and not using them

adapted from <Writer's Craft> by Rayne Hall

#writing#writers on tumblr#let's write#writers and poets#creative writing#writeblr#poets and writers#helping writers#creative writers#resources for writers#writers life#writer stuff#writers community#writers block#writerscommunity#writing process#writing prompt#writing inspiration#writing advice#on writing#writing ideas#writing community#writer#writer community#writer problems#writer things#writer on tumblr#writing practice#fight scene#spears

503 notes

·

View notes

Text

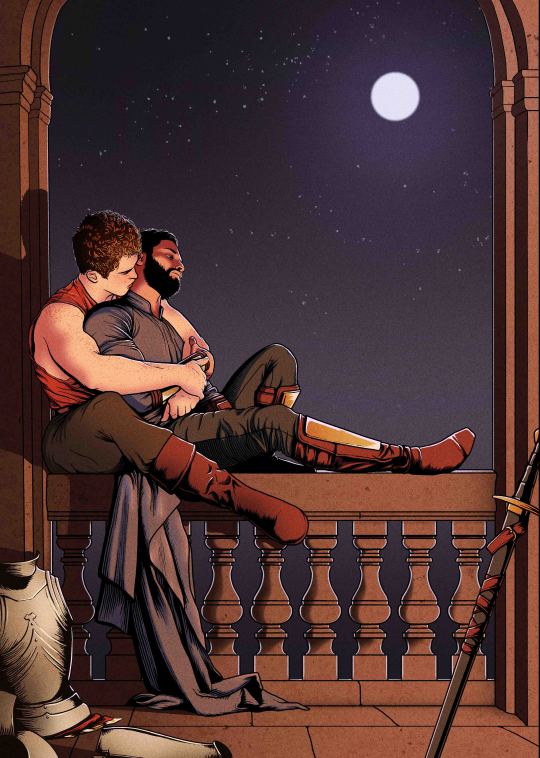

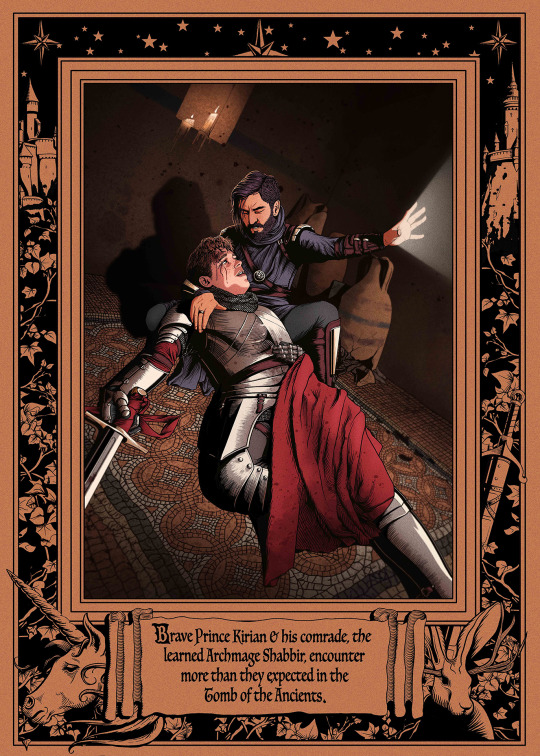

I'm Joe. An illustrator from Colchester, England. With 'Tales From A Gay Fantasia', I am able to combine my love of illustration, creative writing, and design with a lifelong fascination with medieval fantasy. My current goal is to create an illustrated collection of interwoven queer romance and adventure stories within a beautiful and diverse fantasy world.

All my links

You can find links to the individual tumblr posts for each piece of artwork at the bottom of this post or just deep dive into the #gayfantasia tag :D

Artwork links in order of appearance:

"The Look That Stopped The Blade", "Tip Your Bard",

"The Magic That Binds Us", "Sword-Crossed Lovers",

"Mersi's Delivery Servie", "Sanctuary", "The Prince, The Mage, & The Unicorn",

"First Date", "I Got You Baby", "Take Your Himborc To Work Day",

"The Parade (Colour Bleach)"

"Admiration", "The Knight & The Ranger", "The Mage & The Knight"

"Restoration", "Trepidation", "Reunion"

"The Rogue & The Bard", "The Paladin & Her Sorceress", "Reciprocity"

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

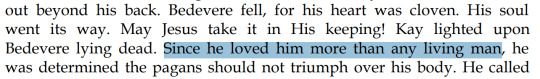

My Illustration for Classics but make it Gay vol 3! The book is on pre order now at http://novaandmali.com/shop full of more queer history fun!

Medieval Pride! I know I have probably missed some folks 😭 but I hope you enjoy the pride gone Medieval parade full of colour coded clothing, doggos, horses and a little zodiac fun cos you know how we all love a little horoscoping!

The original is Les Treis Riches Heures de Duc Barry month May (because alas the june image wasnt as fun for a pride set up!)

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Who was Paracelsus?

Paracelsus was the screen name of Philippus Bombastus Romastus Fantastus Supercalafragalisticexpialadastus von South-Stuttgart-Next-To-The-University-Cafeteria-With-The-Zig-Zag-Roof. His name Paracelsus literally means "Better than Celsus." We do not know who Celsus may have been, but the name is likely a reference to St. Jerome Para-Ezra of Baton Rouge, who was known in his time to have been far better than Ezra.

Paracelsus invented many of the medical techniques used from medieval times to the modern medical revolution, including bleeding, leeching, exsanguination, draining blood from the patient, and ultra-hemorrhagic-cleansing. He also coined the phrase "Only the dose determines the poison," as well as its corollary, "You can eat anything, just some things you can only eat once," and the less impressive but better known, "He who smelt it, dealt it." This was all considered an advancement over the old theory of bodily humors, which is why Paracelsus's friends all said he was a humorless bastard, or so he kept claiming.

Paracelsus was married in a Rosicrucian ceremony based on the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, which was of course preceded by Chemical Engagement and a Chemical Romance involving a black parade, the theatrical faking of several deaths, and a great deal of sodium (a mass scientifically abbreviated as Na Na Na (Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na Na). To whom he was married is a matter of much debate, with potential spouses speculated to include Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth I, Queen Elizabeth II, Martin Luther, Galileo, Ivan the Terrible, Thomas Hobbes, John Calvin, Catherine Di Medici, the Popes Alexander V-VIII, or possibly all at once.

Paracelsus died in the 1540s after suffering a minor splinter which he treated with his own experimental technique known as "setting the patient on fire and stabbing him with a fork in his balls until he barfs then laughing at him." He was then cremated with his urn displayed at the University of Hohenheim for several centuries, until he was accidentally misplaced during an American tour and is presumed to have been used as ash in some Humboldt Fog Cheese, which was considered an affront to his Swiss heritage.

Also he apparently invented Zinc. Good job.

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

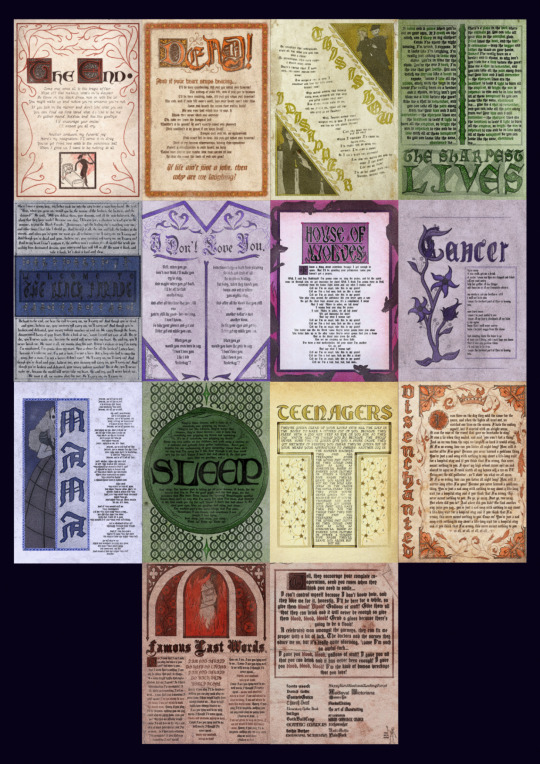

finished this project ive been working on- a lyric booklet for the black parade inspired by illuminated medieval manuscripts! i think a lot about how the album was inspired by medieval cycle plays and always thought it would be fun to do something with that aesthetic. you can read it here!

#was inspired by mcrzines zine prompt but im not sure if it classifies as a zine?#tbp manuscript#my chemical romance#the black parade#mcr#mcr fanart#mcr the black parade#i feel like this is a weird and niche crossover so im not sure if it appeals to anyone but me haha#but i had fun!#im also gonna post some of the pages here on their own!#mine

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Are horned helmets actually a thing? How would a fantasy race that has horns... compesate for them?

Only in the sense that people do make them for various reasons. There are ceremonial and ornamental horned helmets dating back into the bronze age. There's a famous example that was gifted to Henry the VIII in the 1500s.

As I said, some were made for religious ceremonies. Usually for priests of horned deities (there's a bunch of these.) In these cases it could be made from either metal or actual animal horns. I'm not familiar with much beyond that in these cases because archaeology and anthropology are a little outside my area of expertise. I'm not aware of any religions that still use horned helmets, but it really wouldn't surprise me if it pops up from time to time. I'd also categorize head gear with attached antlers in the same range here. It wouldn't surprise me if it exists, or existed, but, I'm not aware of any examples.

We have depictions of horned helmets from knights at tourney in the 14th century. (And at least one surviving example.) This is probably legitimate. At least, in so far as that the knights may have worn horned helmets to show off. Though, this head gear wasn't something that a knight would wear onto the battlefield.

The modern image of the horned helmet (and the association with Vikings) has a lot more to do with Wagner's The Ring Cycle, and particularly stage performances of that opera. (It's not technically original to that, but the horned Viking was a 19th century German invention.) This also the source for a lot of novelty hats and helmets that you can readily obtain today.

The problem with horned helmets on the battlefield is that it gives your opponent something to grab in a tight melee. And letting someone get control of your head in a fight is a very bad thing. This is made worse with a helmet, where the foe could easily unseat the headgear, potentially blinding the wearer long enough to kill them.

There are historical examples of horned helmets intended for use on the battlefield. The Japanese are probably the easiest example to reference. However, in these cases, the horned helmets were worn, specifically, by officers, and communicated their authority to their soldiers, so they could more effectively issue orders. Somewhat obviously, that's not someone you're going to see in the meat grinder of the front lines. (Also, in most cases, these horns were oriented vertically, and were probably too small to grip. The surviving knight's helm, mentioned above, also featured vertically mounted horns.)

Similarly, if you had examples of horned cavalry helms (particularly vertically mounted horns) used by late medieval or even early modern cavalry, that wouldn't surprise me. Especially if that was part of their parade dress. While it's not horns, the winged hussars come to mind as another example of absurd ornamentation on cavalry, and they continued operating until the late 18th century.

Now, as for a fantasy race, I could see grabbing their horns being a very, very, bad idea. This is somewhat informed by the fact that the first example that comes to mind is the minotaur, where grabbing their horns is probably a pretty good way to ensure you're going to get a horn run through your chest. Ultimately though, it becomes a bit like grabbing someone's hair. You've just committed a limb to limiting their head's range of motion, while leaving both of their arms unfettered. On the battlefield, that sounds like a great way to get stabbed in the armpit and die.

So, they are real in the sense that they existed (and still exist), but their actual use in warfare was extremely limited due to practical considerations. That said, people have thought they looked cool for thousands of years, and they're around. Though the Viking helmet is a complete fabrication by 19th century Germans trying to make the Vikings look cooler.

-Starke

This blog is supported through Patreon. Patrons get access to new posts three days early, and direct access to us through Discord. If you’re already a Patron, thank you. If you’d like to support us, please consider becoming a Patron.

178 notes

·

View notes