#writing conflict

Text

Fight, flight, freeze, fawn

When someone has adrenaline, they react with one pf the following four responses. If you want to write realistic characters, consider which they would do and then include it in your writing, even if it's very minor, it makes a big difference.

Fight; In an attempt to overcome the complication, the person fights back. Whether this is physical, emotional or spoken, the aim is to best the problem and be on top.

Flight; In an attempt to overcome the complication, the person flees. This can be physical (running from a predator) or mental (stop thinking about the problem). This reaction aims to put distance between the person and the problem.

Freeze; In an attempt to overcome the complication, the person stops their previous action. This can be physical, to avoid being seen or mental, like their thoughts or words stop. The freeze reaction aims to conceal themselves from the complication.

Fawn; In an attempt to overcome the complication, the person attempts to appease. The fawn reaction aims to avoid conflict, physically (talking to complication) or mentally (passing things off)

Keep in mind; sometimes their reactions aren't successful.

Thanks for reading, have a good day!

#writers#novel writing#writeblr#writing#authors#author#books#wip#write#writing tips#writing community#writing advice#on writing#creative writing#fight or flight#writing conflict

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Problem: The Scenes Are Void of Meaningful Conflict

Problem: The Scenes Are Void of Meaningful Conflict

Solution: Character growth and story arcs don't occur in isolation. Conflict-guided scenes and conflict-guided storytelling, more broadly, open the narrative to moments in which the characters are continuously tested to validate their knowledge, skills, or relationships.

To drive the story forward with measured purpose, focus on building, developing, and testing a character's desires. If necessary, implement story or relational dynamics to economically assess, judge, and curate a character's failure (and the consequences thereof). Conflict needn't be grandiose; writers must be in tune with the different levels, types, and intensities of conflict that drive their story. Conflict should be multifaceted.

Writing Resources:

A Few Words About Conflict (Glimmer Train Press)

Conflict Thesaurus (One Stop for Writers)

6 Secrets to Creating and Sustaining Suspense (Writer's Digest)

Emotions in Writing: How to Make Your Readers Feel (Jericho Writers)

The Primary Principles of Plot: Goal, Antagonist, Conflict, Consequences (September C. Fawkes)

How to Master Conflict in Young Adult Fiction (Writer's Edit)

Failure, Conflict, and Character Arc (Writers in the Storm)

❯ ❯ Adapted from the writing masterpost series: 19 Things That Are Wrong With Your Novel (and How to Fix Them)

#writeblr#writing tips#writing advice#writing conflict#fiction writing#novel writing#writing problems#writeprob#meaningful conflict#story dynamics#character dynamics#ya fiction#writing suspense#writing mystery#writing failure#character arcs#principles of plotting

461 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Authors Write Fictional Wars

Some of our favorite novels include wars. They might stretch over a trilogy or build within a single book. Writing one might seem staggering, but it just takes a different planning approach. Use these tips to write a fictional war for your next story and make your readers feel like it really happened.

Foundational Factors to Consider

1. Your Opposing Sides

Wars always have at least two opposing sides. Start there and develop them before deciding if you need a third or fourth side involved. Cover details like:

What does each side want?

What would each side settle for?

What is each side’s worst-case scenario?

What is each side’s hard no? (What wouldn’t they sacrifice or do to win their cause?)

2. Who Supports the Opposing Sides and Why

As a war progresses, each side loses resources. They start running out of money, soldiers, and whatever public support they had when they started the war due to citizens losing their loved ones or sacrificing for the cause.

Your protagonist and antagonist will need to ask for help eventually. Who would support them and why?

There are numerous reasons why someone might pick one side of a war over another. Politics and economics are often the first things leaders consider. The morality behind each side is another factor.

Consider the American Revolution. Many historians believe America would have lost without France sending money, troops, food, and supplies. Why would France support a budding nation over Great Britain? People argue it was because the French:

Wanted to humiliate the British king

Wanted to hurt their British military rival by partnering with America

Wanted to weaken the British kingdom by ending the colonial taxes they benefited from

Wanted to gain power on a global standing by overcoming Great Britain and rising as America’s first ally

These reasons are great examples of what your novel could include. Another country, kingdom, or group could rise in sudden support for your protagonist or antagonist, ultimately throwing chaos into the determined path of war for better or worse.

3. The War’s Terrain

People can break into battle almost anywhere, depending on your fictional world. Your characters could fight:

On land

On sea

In space

In the air

Underground

Online

Some terrain also comes with other considerations. If your war happens on an ocean, will storms and hurricanes affect battles or the ultimate outcome? How will the soldiers and leaders on both sides deal with the weather?

Note these possibilities as you plan your novel. You can add them in as background or crucial plot devices once you have a skeletal structure in place for your story.

Need help remembering everything you’ve imagined? Try making a map and keeping it wherever you write.

4. What Would Make Each Side More or Less Powerful

There’s always something that could give one side an advantage over the other. It’s often in an unexpected way, although you could make the advantage a goal. The bad guys might feel confident in their ability to win, but they have a secret mission to develop a new weapon just to give them a greater advantage.

Other factors to consider would be one side or another doing something like:

Discovering or enacting a magic system

Eliminating a crucial resource their enemy depends on

Removing funding that makes their enemy able to fight by befriending or overcoming their enemy’s financial backers

Changing the positive or negative public perception of the other side’s reason for fighting to change national morale

Doing something that makes one side’s leaders more or less moral (which could change public perception, the soldiers’ vigor, the leadership’s advisory team together, etc.)

6. What Kinds of Conflict You’ll Write

There are two types of basic conflict you’ll likely write when navigating a fictional war. You may not need both if your story is shorter, but adding both makes the plot more realistic.

First, there’s external conflict. You’ll have at least two opposing sides on some kind of battlefield, sneaking around on spy missions, planning surprise attacks, etc.

Secondly, there’s internal conflict. Soldiers might start fighting amongst each other, people in leadership positions could lose trust in each other, citizens might turn on their country’s cause for one reason or another, etc.

7. What Weaponry Your Characters Will Use

The weapons used in your war depend on numerous factors. It will draw from the genre you’re writing, the time period your story takes place, the advancements made in each civilization’s weaponry prior to the war, and any advancements made while the war goes on.

Examples of these could be:

Guns

Swords

Bows

Bombs

Drones

Armed ships

Armed space ships

You should also consider if one side’s weaponry is more likely to change during the course of the war. That’s more plausible if your story or characters change locations where regional cultures use different weapons. Also if the war spans years, people will naturally develop new weaponry during that time.

If you want extra details to daydream about, think about which weapons will become outdated during your story. Some will prove less useful due to complicated usage or cleaning. They also may not work, like if your science fiction characters follow their enemy underwater, but their laser guns require a dry atmosphere to function.

Include Emotional Plot Arcs

Writing always involves some kind of emotional work that results in a plot arc. It keeps the reader engaged by evoking their core feelings. That’s what makes a novel different from a textbook (in a very basic sense).

Work on details like these to find what emotions will be most present and relevant to your story:

Your overall theme

Your characters and what they experience

The action your characters will go through

How the above action will change your characters by affecting their loved ones

What your characters’ goals mean to them emotionally

If your characters’ will undergo things that change their perception of their world, leaders, country, or themselves

You don’t need all of these things to have an emotional plot arc, but they’re relatable human elements that can drive your plot right into your readers’ hearts.

Avoid Some War Story Tropes

Tropes have a bad reputation that I don’t think is entirely deserved. People recognize them as overdone stereotypes, but sometimes they’re useful.

When you’re writing a war, you’re going to have necessary tropes like:

The hero

The unit or squad

The antagonist

What they undergo and who they become is how you make them fresh concepts for your readers.

Some tropes aren’t helpful because they’re what readers expect from every story. If you give them what they expect, your story isn’t as engaging (unless you get the occasional reader who exclusively reads war novels and never tires of overdone tropes).

Keep these in mind as things to avoid, unless you have an ingenious way to make them a brand-new experience:

One soldier dying in another’s arms

A character dying by going out “in a blaze of glory”

Characters using guns in ways that are obviously wrong (i.e., firing more bullets than the gun-type/model holds)

Getting military rank incorrect (if your characters exist in a real-world, already existing military structure)

Injury-proof characters (even your protagonist will eventually encounter some physical harm, whether it’s illness in bad weather or getting shot on a battlefield)

You can check out this great resource to discover more tropes to avoid/consider as you draft your plot outline.

-----

If it feels like writing a war over the course of a book or a series is challenging, you’re not alone. There’s a lot to consider to make it have an engaging flow.

Keep notes on things like these to develop your story as much as possible before starting your first draft. You can always go back and add or edit things out as needed while developing it. Writers do this all the time—you don’t need to get any manuscript perfect on your first try.

#writing war#writing warfare#writeblr#writing advice#writing tips#writers of tumblr#creative writing#writing#writing inspiration#writing community#writing help#writing resources#writing action#writing conflict#writing batlles

537 notes

·

View notes

Text

Failing with Momentum

Last time we talked about antagonists so this time we’re talking about conflict. Sometimes I think writers are afraid to allow their characters to fail. Trust me, there’s a big difference between characters making poor decisions that seemed good in the moment (or failing), and being the protagonists in slasher horror movies. Your characters can be a bit stupid, and fail often, without ruining your plot or characterization.

1. Fail Forward

One way we do this is by allowing them to fail forward. This means that your plot actually relies on their failure, rather than just on their successes. They get totally rejected for the school dance, but that leaves them out in the hall to witness something they weren’t meant to see. They get caught sneaking around in the bad guy’s lair, but now they know their accomplice is actually on the other side.

This takes reworking of your entire plot, so consider while crafting your outline how a failure can get the character to where they need to be rather than a success.

2. Everything comes with consequences

Another way to allow your character to fail is to not reveal that they’ve failed right away. Most decisions we (and characters) make aren’t so black and white—right or wrong. It shouldn’t be obvious right away when a character has done something stupid—we reveal that it was stupid later on, when consequences come back to haunt them.

So another way to say “let your characters fail” is just “let your characters face consequences.” Maybe a decision isn’t necessary stupid, or ‘bad’. Maybe it allows them to achieve something they really needed to. However, it should also come with unintended consequences—a negative to the positive.

3. Failing is a chance to show their strengths

When something (usually caused by the antagonist) stands in their way, it’s just another chance for them to demonstrate what they’re strong at. Say the antagonist kills the person who has all the answers before the protagonist gets to talk to them, now they have to pivot—maybe they dig up the information through research, or find someone related to talk to, or reach out via medium to the spirit realm, whatever.

This pivoting is the kind of challenge that allows your character to grow. Their path isn’t a straight-shot, easy romp through a meadow but one filled with twists and disappointments and frustrations and challenges. They are forced to do things they maybe never would have, and this leads to them thinking about themselves or their worlds differently.

What other ways are there to fail forward?

#writing#creative writing#writers#screenwriting#writing community#writing inspiration#filmmaking#books#film#writing advice#failing with momentum#conflict#writing conflict#antagonists

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Deal with Character and Plot: Which is More Important?

All stories have characters and plot.

Sometimes as writers, however, we pour all our focus into one of these aspects, overshadowing plot in favor of character, or getting too caught up in plot and leaving character for last. Really, both are the nuts and bolts of story — they work in unison, thriving in tandem. Without the other, the story just falls flat. But, there’s a little something that is the glue between plot and character.

So what is this glue?

That, my friend, is conflict.

Conflict is the glue that brings together these two aspects, creating balance and making a compelling and engaging story. All good stories have conflict.

It’s helpful to remember that plot is the sequence of external events in a character’s environment that get the ball rolling, whereas character give a window to the internal, the emotional. Internal conflict is often of the character’s own making: a secret motive, a battle of emotions, the opposing want versus need, the dissatisfaction in their life, the indecisions or hesitations.

A character tends to get affected by the external events. A messy divorce may lead to one character’s depression before they finally motivate themselves to get a new date, going through multiple failed attempts until they meet their second-soulmate. A character getting a new job may catapult them into —what was supposed to be a fresh start— a waking nightmare as they try to navigate their unfair, demanding workplace.

With these two examples, we can pinpoint their internal and external conflicts. In the first, we have the character’s external conflict of a heart-breaking divorce and the struggles of moving out and getting the papers settled. As for the internal conflict, this character goes through bouts of depression, wondering if she’ll find anyone for her, before finally getting encouraged to get back out into the dating pool once again, helping her to discover that nothing is too-late or at the end of road.

For the second example, the external conflict is the character navigating their new environment, driven up the wall from tedious work and snobby coworkers, but they can’t leave because of *reasons*. Their internal conflict, in turn, is their dedication as to not quit coupled with their eventual desire to climb the ladder of success.

We can start to see here that there’s a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the external and internal: one cannot exist without the other. How a character might see the world can impact their relationships and other external factors, such as their environment. Similarly, external events can prompt a character to react or spark inner conflict that they have to deal with in one way or another.

I hope this is helpful. Thanks for reading!

#writing advice#fiction#writing#creative writing#writing tips#internal conflict#external conflict#character#plot#writing conflict

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is Your OC’s Internal Conflict?

Internal conflict is key to writing a character-driven story and helping readers emotionally connect to your characters. The external conflict would be, say, the Hex Squad defeating Emperor Belos and the Emperor’s Coven, but the internal conflict would be Amity breaking away from her mother’s influence, or Willow rebuilding her self-worth after years of bullying broke it down. It relates back to their personal journey of self-growth as they conquer their inner demons rather than an external force

If it helps, feel more than free to comment or reblog to share your own characters’ internal conflicts

#internal conflict#external conflict#writing conflict#conflict#the owl house#writing#writers#writeblr#bookblr#book#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers of tumblr#writer#how to write#on writing#creative writing#write#writing tips#writers and poets#writblr#female writers#writer things#writerscreed#writer problems#writing is hard#writing advice#writing life#original writing

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

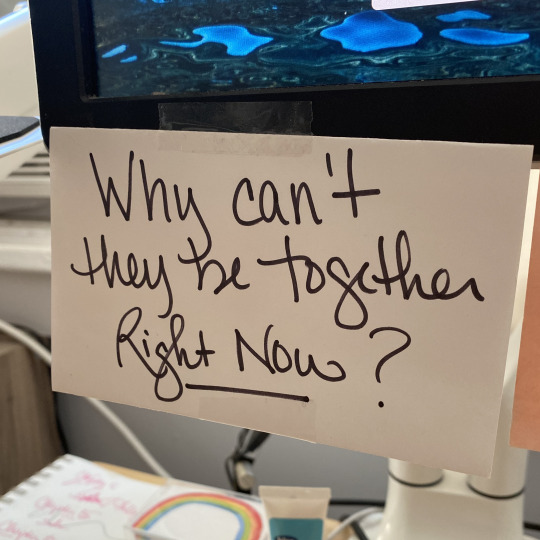

The most important question I ask myself while writing romance, five years apart and much classier now, thanks to Kate Clayborn's incredible needlepoint skills.

I'm a conflict writer (this will surprise no one, as I feel like you'd be hard pressed to find a romance writer who loves an explosion more than me), so this question is my lodestar when I work. I ask myself after every scene: Why Can't They Be Together Right Now. This isn't a vague question for me while I'm writing -- I literally write the answer down in a notebook.

"Chapter 1, Scene 1: They haven't met yet."

"Chapter 7, Scene 2: He's just been stabbed. Right now is not a good time."

"Chapter 18, Scene 1: He thinks she deserves someone far better than he is (dummy)."

The goal is for the reasons to evolve and change, and reflect both what I think of as the plot (what's going on externally in the book) and the story (what's happening internally in the book).

If the answer is the same for too long (say, two or three chapters?), I know the book is lagging, and I have to amp it all up.

#writing with Sarah#why can't they be together right now#writing conflict#writing romance#get friends who are virgos and have needlepoint skills

898 notes

·

View notes

Text

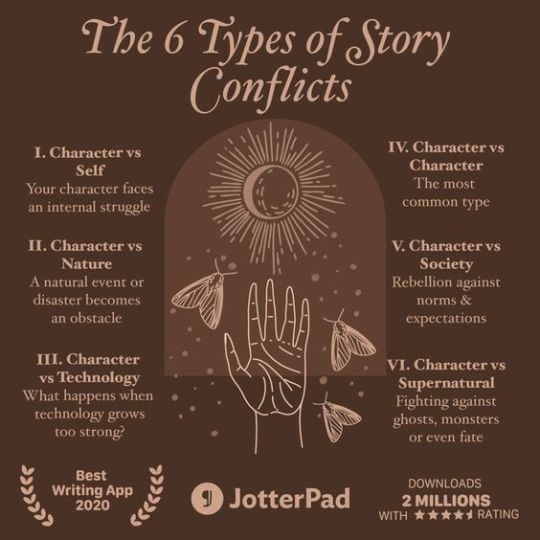

"While there are many models for conflict, with disagreements on how many categories and subcategories exist to create the tension your story needs, I prefer to align with Aristotle and stick to the basic three (with updated nomenclature).

The only categories I need are Characters vs. Themselves, Characters vs. their Environment, and Characters vs. Others. Using Aristotle’s broad categories helps me simplify the process of selecting quality obstacles to boost conflict for my main characters."

#writing conflict#writeblr#writers of tumblr#nanowrimo 2023#nano 2023#nanowrimo#national novel writing month#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#creative writers#writing inspiration#writerblr#writing tips#writblr#writers cornter#tips for writers#helping writers#help for writers#advice for authors#writing advice#let's write#writers block#writer's block#beat writers block#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#writing tips and tricks

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would you write a conflict with more than two factions? Good faction vs. Evil faction kind of seems too simple and overdone. Any tips on adding different groups clashing over different ideals but each ideology having its own pros and cons?

Figure out what the source of the conflict is. Where does it stem from? What are all the details of the event/reasoning?

Your characters don't have to know all the details, and you don't have to write it into the story, but you should probably know them so that you can see how it can be misinterpreted by all the parties and from all angles.

Was it an honest mistake, or did someone seek to get the upper hand by doing something sneaky/'wrong'?

What information about the truth are the various parties missing?

Is one party manipulating another to gain the upper hand over both? At what point (if at all) do the others realise this?

Is it a pointless, generational issue, à la Montagues and Capulets?

Do some factions get along better than others? Is there hope for reconciliation?

I guess you have to think how your characters/factions think, and examine the 'why' of it.

#sorry if that's really vague#i'm sick as a dog right now#and on a lot of cold medication yay#writing advice#writing conflict#writing#anon ask

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips: Conflict, Tension, and Suspense

Conflict:

A struggle between opposing forces, propelling the narrative.

Forms: Character vs. character, character vs. self, character vs. environment.

Example: "Avatar: The Last Airbender" - Aang’s quest to oppose the Fire Nation’s war of conquest propels the plot.

Tension:

Definition: Emotional strain from unresolved conflicts or challenges.

Build-up: Simmers beneath the surface, creating a constant undercurrent.

Example: “The Hunger Games” - In the early stages of the Games, the ambiguity of Peeta’s intentions give rise to tension between Katniss and him.

Suspense:

Definition: Anticipation of an impending event.

Nature: Heightened state of excitement or anxiety.

Example: "Murder on the Orient Express" - Revelation of the murderer kept a mystery until the end.

Relationship between Conflict, Tension, and Suspense:

Conflict drives the narrative, creating obstacles for characters.

Tension arises from unresolved conflicts, building through anticipation.

Suspense is similar to tension in that both are the anticipation of a happening. Tension is defined. We know the conflict, characters, and stakes involved. Suspense is vague. We know something is about to happen but we usually do not know what, or how, exactly.

Imagine tension as a taut string connecting a character to unresolved conflict. The conflict acts like a force, pulling the character through the plot.

Imagine suspense as a character, well, suspended in open water. They face unknown dangers, such as a potential monster, storm, or rogue wave. We are aware that something bad is about to happen, but not exactly what.

This is part of my Writing Tips series. Everyday I publish a writing tip to this blog.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Theory - Conflict 101

THEORY

goal + obstacle = conflict -> plot

You may have heard that a story needs conflict, but what does that mean?

No, it's not explosions. Or murder. Or smut.

Your character wants something, that's the goal. Something is in the character's way, that's the obstacle. The way your character deals with the obstacle to reach their goal is what makes an engaging conflict.

You see this on a plot level as well as on an individual scene level: Character wants X, but obstacle Y, so they have to go do Z

Conflict is like the engine of the plot, so if it's missing in a scene, then it's likely to feel redundant, boring, as if the story came to a halt (because it did; the engine stopped).

The goal and obstacle pair generally appear in two orders, with a "reaction" element:

Character sets a goal, but an obstacle happens, so the character reacts by changing course

Something happens (obstacle), character reacts to it and decides on the next action (goal)

You can alternate between the two, then you get something like this: character tries to accomplish something, something gets in their way, forcing a new approach, character reacts to the changes and decides how to move on from here, sets a new goal, tries to reach goal, faces obstacle...

This can also keep your character active rather than passive. Even in a reactionary scene, your character is responding and making a decision, rather than being a puppet to external forces. It can be smart to not have too many reactionary scenes back-to-back, as this can also feel passive. The goal-obstacle-reaction type scenes don't really have this problem and you can intersperse them with reactionary scenes now and then for variation.

You can have one major goal and many smaller goals. The goal(s) can also shift over the course of the story.

If you struggle to think of an obstacle, ask yourself: what is preventing my character from achieving their goal right now? Why can't they walk up to the villain and defeat them? Why can't they pull their love interest into a kiss? Why is your story longer than two paragraphs?

Ideally, goals and obstacles (and conflicts) are interwoven with character development, theme, etc., making for a solid plot where all these elements form one smooth fabric together. As a beginner, it's alright to first pick one thing to exercise rather than trying to balance all these things at once. Learn to create these bare bones of a plot and then improve upon that foundation.

EXAMPLE: Revenge of the Sith

Anakin would like Padmé to not die. = goal; He doesn't know how to prevent it. = obstacle

Stop the Sith = goal; Not knowing who the Sith Lord is = obstacle

These form conflicts and they push the plot forward. There are several smaller goals, like defeating Dooku/saving the Chancellor, preventing Palpatine from dying, manslaughter, killing Obi-Wan...

A scene with the goal - obstacle - (reaction) order: Anakin wants to use Palpatine's knowledge (goal), but Mace Windu is about to make that permanently impossible (obstacle). Thus, Anakin needs to pivot from yelling to slashing in order to reach his goal.

A scene with the obstacle - (reaction) - goal order: Anakin, the superstar Jedi, has just helped a Sith Lord kill a Jedi master (obstacle/problem; goes against the bigger "stop the Sith" goal). This has an effect on him (reaction; "What have I done??") and leads to a decision: join Palpatine. This then sets him on his next goal(s): destroy the Jedi to prove he's worthy.

Here you see how those two "types" of scenes flow into each other.

EXERCISE

Write two short scenes - one for each type (reactionary and goal-obstacle-reaction). They don't have to be unrelated.

Now, write another two scenes, but this time make them successive.

See if you can do this in the form of a short story: write 5-10 successive scenes.

Celebrate that you've just written a story! :D

These techniques, like so often with writing, need practice to sink in. So write some fun short stories or wacky scenes, and you'll notice you get better the more you do it. Have fun!

#writing tips#writing theory#writing advice#writing conflict#writing#creative writing#writers of tumblr#conflict 101

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

#writing conflict#writing#writers#writers on tumblr#writing community#writerscommunity#writer things#novel writing#writerslife#writing help#writers of tumblr#writing advice#conflict#types of conflict#writers and readers#writing tips

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 Things That Are Wrong With Your Novel (and How to Fix Them)

The original infographic on which this list is based was bulleted with short descriptions (see "All The Things that Are Wrong…" at Hey Writers and FastCompany). It's nifty quantitative data. However, the original article doesn't explore any solutions. So, I spent some time hunting down a few writing resources to fill in the gaps.

The following list of "problems" represents about half of those from the infographic. I tweaked the problem statements, and I drafted the solution text in a feverish rush. No apologies for repeated sources; I have my favorites. Read on:

Problem #01: The Story Begins Too Late in the Novel

Problem #02: The Scenes Are Void of Meaningful Conflict

Problem #03: The Story Has a By-the-Numbers Execution

Problem #04: The Story Is Too Thin

Problem #05: The Villains Are Cartoonish, Evil-for-the-Sake-of-Evil

Problem #06: The Character Logic Is Muddy

Problem #07: The Female Part Is Underwritten

Problem #08: The Narrative Falls Into a Repetitive Pattern

Problem #09: The Conflict Is Inconsequential, Flash-in-the-Pan

Problem #10: The Protagonist Is a Standard-Issue Hero

Problem #11: The Story Favors Style Over Substance

Problem #12: The Ending Is Completely Anti-Climactic

Problem #13: The Characters Are All Stereotypes

Problem #14: The Novel Suffers From Arbitrary Complexity

Problem #15: The Story Goes Off the Rails in the Third Act

Problem #16: The Novel's Questions Are Left Unanswered

Problem #17: The Story Is a String of Unrelated Vignettes

Problem #18: The Plot Unravels Through Convenience/Contrivance

Problem #19: The Story Is Tonally Confused

-------------------------------------------------------

Problem #01: The Story Begins Too Late in the Novel

Solution: Gain traction early; use simplicity, momentum, and a bit of the unknown to carry readers toward the more complex and the improbable. The first chapter is context for what the whole novel is about. Don't wait to pull in readers, don't hesitate to tell readers which characters are the most important, and don't hesitate to expose readers (and the viewpoint character) to the narrative's central conflict. Be upfront about what kind of story you're telling.

Develop a strong sense of who your protagonist is, articulate the protagonist's needs (which may change), and hint at the limits or barriers the protagonist must acknowledge, or defy, to achieve their current or a future goal.

Writing Resources:

8 Ways to Write a 5-Star Chapter One (Writer's Digest)

10 Ways to Start Your Story (The Writers Society)

How To Start a Story That Grips Your Readers (Jericho Writers)

7 Steps for Writing Your Novel's Opening Chapter (The Novel Smithy)

4 Key Elements of Scene Openings (September C. Fawkes)

How to Find Your Writing Style (sunnydwrites; ahbwrites)

Writing Riveting Inciting Action: 7 Ideas (Now Novel)

In Media Res: 6 Steps to Start Stories From the Middle (Now Novel)

Writing Great Beginnings and Endings (Writing Questions Answered)

Problem #02: The Scenes Are Void of Meaningful Conflict

Solution: Character growth and story arcs don't occur in isolation. Conflict-guided scenes and conflict-guided storytelling, more broadly, open the narrative to moments in which the characters are continuously tested to validate their knowledge, skills, or relationships.

To drive the story forward with measured purpose, focus on building, developing, and testing a character's desires. If necessary, implement story or relational dynamics to economically assess, judge, and curate a character's failure (and the consequences thereof). Conflict needn't be grandiose; writers must be in tune with the different levels, types, and intensities of conflict that drive their story. Conflict should be multifaceted.

Writing Resources:

A Few Words About Conflict (Glimmer Train Press)

Conflict Thesaurus (One Stop for Writers)

6 Secrets to Creating and Sustaining Suspense (Writer's Digest)

Emotions in Writing: How to Make Your Readers Feel (Jericho Writers)

The Primary Principles of Plot: Goal, Antagonist, Conflict, Consequences (September C. Fawkes)

How to Master Conflict in Young Adult Fiction (Writer's Edit)

Failure, Conflict, and Character Arc (Writers in the Storm)

Problem #03: The Story Has a By-the-Numbers Execution

Solution: Structure must be impeccable. Except for when it shouldn't be. Formulas are essential. Except for when they're not. Outlines are absolute. Except for when they aren't.

Successful storytelling strategies should flex and shift and evolve as the needs and demands of the story flex and shift and evolve. If you plan to wield an effective structure to buffet your storytelling execution, then research and document the structure that best compliments your story, your characters, your characters' conflicts, and the themes reflected in those conflicts.

Writing Resources:

7 Point Story Structure Explained in 5 Minutes (September C. Fawkes)

How to Actually Use a Story Structure (September C. Fawkes)

Description: 5 Times When You Should (and 4 Times When You Shouldn't) Rely on Description (ahbwrites)

Basic Checklist for Your Story (The Right Writing)

Gothic Literature: A Guide To All Things Eerie (Jericho Writers)

Suspense Definition — Literature: Tips for Writing Suspense (Jericho Writers)

How to Create a Plot Outline in 8 Easy Steps (How to Write a Book Now)

The Progressive Outline: How I Balance My Plotter and Pantser Tendencies (Michael Bjork Writes; Scrawls and Rambles; ahbwrites)

5 New Ideas for Outlining Stories (1000 Story Ideas; ahbwrites)

Problem #04: The Story Is Too Thin

Solution: Does the story lack balance?

Purposeful narrative structure. Effective characterization. Meaningful conflict (and meaningful consequences). Immersive description. Authentic character dynamics. A good story needs all of this and more. But it's okay to be stronger, or more experienced, in crafting one area of storytelling than in others. It's okay for one's attention to drift during the initial drafting phase.

If you know your strengths, then you can lean on them to bolster your storytelling where it counts. If you know your weaknesses or limitations, then you can avoid what frustrates you and maneuver toward what excites you. But take the time to identify what facet of your craft needs work and be open to exploring your weaknesses with further experience, research, and insight.

Writing Resources:

100 Character Development Questions to Inspire Deeper Arcs (Now Novel)

How to Write a Sequel That Satisfies: Simple Guide (Now Novel)

Best Story Writing Websites in 2022 (Now Novel)

10 Signs Your Plot is Weak (and How to Fix it) (September C. Fawkes)

Defining and Developing Your Author Voice (September C. Fawkes; ahbwrites)

How to Pace a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

Description: 5 Times When You Should (and 4 Times When You Shouldn't) Rely on Description (ahbwrites)

How to Focus on One Story (Alyssa Hollingsworth)

Problem #05: The Villains Are Cartoonish, Evil-for-the-Sake-of-Evil

Solution: Villains require just as much character development as the novel's heroes, protagonists, and perspective characters. Effective villainy incorporates consequential decision making, relatable character motivations, believable perspectives and experiences, and most important, intention. When a writer diversifies these facets of a so-named villain's free will, humanity, personal interests, and relationship with the story's main conflict, one is better-positioned to craft a more diverse and more engaging villain.

Writing Resources:

How Your Character's Failures Can Map A Route To Self-Growth (Writers Helping Writers)

Good Character Flaws: Create Complex Antagonists (Now Novel)

50 Questions to Ask Your Antagonist (Alyssa Hollingsworth)

Antagonist Starts Good, Becomes Drunk With Power (related, master list) (Writing Questions Answered; ahbwrites)

16 Villain Archetypes (Chosen by the Planet; ahbwrites)

How to Give Your Antagonist a Little Humanity (Fiction Writing Tips; ahbwrites)

How to Write the Perfect Villain (Jericho Writers)

How to Build an Antagonist (How to Fight Write)

Negative Trait Thesaurus (Evil) (One Stop for Writers)

Theme and Symbolism Thesaurus (Evil) (One Stop for Writers)

Problem #06: The Character Logic Is Muddy

Solution: Investing in realistic characterization will give a novel the curious details and sense of familiarity readers will readily absorb. Good character logic means providing original characters with the agency to speak, act, and react with authority. (It also doesn't hurt to have a character or two who are really good at faking it.) But it's not enough to simply imply a character's sense of self through dialogue and action. Writers should aim for a level deeper.

Don't write characters, write character arcs. Don't write character flaws, write character flaws that make characters curious, enticing, or attractive. Craft inimitable dialogue, encourage characters to engage their environment, and remember to hold characters responsible for their actions.

Writing Resources:

3 Redemptive Character Types (September C. Fawkes)

6 Ways to Write Truly Terrifying Villains (The Novel Smithy)

What Is Pathos in Literature? A Complete Guide (Jericho Writers)

Character Motivation Thesaurus (One Stop for Writers)

"I don't think you need all the backstory in the world..." (advice from Brennan Lee Mulligan, TTRPG gamemaster)

How to Improve Your Secondary Characters: 6 Fresh Ideas (Em Dash Press)

Some Quick Character Tips (Coffee Bean Writing)

The Importance of The Unlikable Heroine (Claire Legrand; ahbwrites)

Don't Design a Character, Design a Character Arc (avalera; ahbwrites)

How to Write Character Arcs (Helping Writers Become Authors)

Problem #07: The Female Part Is Underwritten

Solution: Frame and establish female characters who are their own and who can hold their own. Obviously, character-building must be done with care, but the emphasis on writing female characters well is not misplaced. Authors in the majority of those published often get away with female characters that are relegated to the role of the conveniently unprotected, the buddy, the substitute wife/girlfriend, the pawn/sacrifice, the hot chick, and/or the stoic action lady who can do anything because that makes her cool.

Write female characters with their own intelligences, experiences, shortcomings, and successes. These characters must come into their own organically, and they must engage the narrative (and readers) in a way that demonstrates their value without siphoning their agency.

Writing Resources:

Make Them Female (Horrible God)

The Importance of The Unlikable Heroine (Claire Legrand; ahbwrites)

100 Character Development Questions to Inspire Deeper Arcs (Now Novel)

We Need to Talk About Cold Women (HuffPost)

Writing a "Strong Female Character" That Isn't Heartless (Writing Questions Answered)

Strength is Relative: Female Characters, Gender Stereotypes, and Writer Authority (ahbwrites)

The Heroines of YA Dystopias Have All These Traits in Common (Refinery29; ahbwrites)

Female Characters to Avoid in Your Writing: An Illustrated Guide (The Caffeine Book Warrior; ahbwrites)

On Mary Sue (How to Fight Write; ahbwrites)

Core Principles of Crafting Protagonists (September C. Fawkes)

4 Ways to Unlock Your Character's Unique Voice (The Novel Smithy)

Problem #08: The Narrative Falls Into a Repetitive Pattern

Solution: Does the story begin at the right point? Are the characters introduced in scenes where they exert the right influence? Are the novel's emotional beats consistent (or meaningful)? What's the tempo like? Is the pacing balanced and purposeful at the sentence level, scene level, and act level? Is the story's use of description unique and dynamic? What's the difference between the author voice, the narrator voice, and the character voice? Be as flexible or inflexible as needed, but above all, be willing to learn.

Writing Resources:

Never Lie Beyond What You're Capable of Selling (How to Fight Write)

How to Craft Your Protagonist's Inner and Outer Journeys (The Novel Smithy)

5 Ways to Keep Reader's Interest When They Know Something the Character Doesn't (Writing Questions Answered)

Variations on Story Structure: A List (September C. Fawkes)

8 Common Pacing Problems (September C. Fawkes)

How Structure Affects Pacing (September C. Fawkes)

Quick Plotting Tip: Write Your Story Backwards (bucketsiler; ahbwrites)

What Is Pacing in Writing? Mastering Pace (Now Novel)

Problem #09: The Conflict Is Inconsequential, Flash-in-the-Pan

Solution: Many authors struggle to contrive meaningful conflict such that it either shapes or speaks critically to the trajectory of the characters it touches. Conflict is not a consequence or a corollary of scheme or impulse; conflict should develop as the story develops and grow as the character dynamics grow.

Explore character through conflict by reinforcing their goals and their perceptions (of reality), as well as the plausibility of maintaining either. Use conflict to reveal blind spots, biases, or fears. Conflict doesn't narrow the possibility of who characters are, or what the story might convey; conflict opens characters (or readers) to new methodologies, new stakes, and possibly new goals, as a result of enduring or overcoming the fracas in question. Conflict adds depth.

Writing Resources:

Conflict Thesaurus (One Stop for Writers)

Need Compelling Conflict? Choose A Variety of Kinds (Writer's Helping Writers)

How to Draw Readers in Through a Character's Choices (Writers Helping Writers)

Exactly How to Create and Control Tone (September C. Fawkes; ahbwrites)

Are Your Conflicts Significant? (September C. Fawkes)

Tension vs. Conflict (Hint: They Aren't the Same Thing) (September C. Fawkes)

How to Write a Dystopian Story: Our Gide (Jericho Writers)

Plot Conflict: Striking True Adversity in Stories (Now Novel)

How to Use Central Conflict and Drama to Drive Your Novel (Now Novel)

Problem #10: The Protagonist Is a Standard-Issue Hero

Solution: There different types of heroes. There are different types of villains. And the multitude of stories in which these various types of characters might interact require differing levels of focus. Not all heroes must have a tale of overcoming adversity. Not all villains need a tragic backstory. Not all comedy stories require a "meek schlub" to come out on top. Not all suspense or thriller tales require a "world-weary detective" fighting for emotional validation or recompense.

Diverse character types help drive diverse stories. Challenge how archetypes and standard-issue definitions traditionally render a "hero" or a "villain" in a story. Important Note: Don't give in by forcing a character to fit an established mold by the story's end.

Writing Resources:

Guide to Writing an Unlikable Protagonist (Words and Such)

How to Craft the Perfect Antihero (Writer's Digest)

How to Write an Anti-Hero Readers Will Adore (The Novel Smithy)

Types of Heroes: Crafting Your Characters (Jericho Writers)

How to Write Supporting Characters in Fiction (Jericho Writers)

10 Ways to Write a Chosen One That Won't Annoy Readers (The Novel Smithy)

Being the Best at Something (One Stop for Writers)

50 Questions to Ask Your Antagonist (Alyssa Hollingsworth)

How to Build an Antagonist (How to Fight Write)

Male Protagonists to Avoid in Your Writing: An Illustrated Guide (The Caffeine Book Warrior)

Problem #11: The Story Favors Style Over Substance

Solution: Writers commonly risk stumbling into the crevasse of convenience, no matter the genre (e.g., action must be cool or flashy, comedy must be glaringly funny, horror must be unremittingly scary). The primary fault lines for these seemingly innocent errors are twofold: inexperience and immaturity. That is to say, the more one reads and the more one writes, the greater one experiences, learns, and empathizes with a greater array of storytelling styles, techniques, and attitudes. Writing a more dynamic and engaging story that leaps beyond the crevasse of style over substance requires an eagerness to learn, a willingness to experiment, and an openness to difference.

Writing Resources:

8 Ways to Write a 5-Star Chapter One (Writer's Digest)

Building a Bold Narrator's Voice: 5 Methods (Now Novel)

How to Avoid Plot Armor (Coffee Bean Writing)

10 Tips for the Middle of Your Story (Coffee Bean Writing; ahbwrites)

Avoiding Plot Armor (How to Fight Write)

How to Absolutely Wreck Your Audience With a Character Death (lunewell)

Writing Description: Make Introspection More Engaging (ahbwrites)

How to Frame Scenes Like a Filmmaker (Kristen Kiefer)

Shakespeare's Genius Is Nonsense (Nautilus)

Problem #12: The Ending Is Completely Anti-Climactic

Solution: Endings can be dramatic. Endings can be a little ambiguous. Endings can be bittersweet. Endings can be simple surprises. Endings can be unique and unresolved. Endings can reverse motives, reverse perspectives, or reverse fortunes. Endings can be complex webs that tie up every single loose end. Whatever the author's preference, endings shouldn't read as if the last 10 pages were cut off.

But knowing how to end a story is not an isolated challenge. To end a story properly and effectively, the author must know how the story begins, how its characters evolve, and how these dynamics transform over the course of narrative's varying points of tension and conflict. Recall, how does the story begin and why? How, specifically, do the characters evolve? And what compels them to do so? Where and how do the story's internal and external conflicts converge? Endings follow a few essential rules: endings require context, endings must be plausible, and endings must connect to the narrative's key elements.

Writing Resources:

Figuring Out Where to End a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

Writing Great Beginnings and Endings (Writing Questions Answered)

Feeling Overwhelmed by Plot Points (Writing Questions Answered)

What Is the Dénouement of a Story? Your Guide (With Tips) (Jericho Writers)

How to End a Story Perfectly (Jericho Writers)

Story Climax Examples: Writing Gripping Build-Ups (Now Novel)

How to End a Novel: Writing Strong Story Endings (Now Novel)

Tension vs. Conflict (Hint: They Aren't the Same Thing) (September C. Fawkes)

Utilizing 3 Types of Death (September C. Fawkes)

10 Signs Your Plot is Weak (and How to Fix it) (September C. Fawkes)

Problem #13: The Characters Are All Stereotypes

Solution: To be more than a collection of tropes, characters must be emotionally differentiated, possess myriad insecurities, battle visible and invisible vulnerabilities, willingly blur their own logic to achieve what they perceive as necessary, and debate their own flaws. Solid characters, well-rounded characters, and well-defined characters give readers a reason to stay engaged.

To craft these characters, authors should be conscientious of what internal rules the story's characters follow, what flaws these characters must overcome, and what trajectory each character arc takes in parallel to the overall narrative arc. Not every character needs to know who they are or how they want to influence the story to stick in readers' minds, but the author should have a good grasp how the character grows (or regresses) relative to how they engage the story's central conflict or theme.

Writing Resources:

10 Traits of a Strong Antagonist (Fiction University)

The No-Effort Character Sheet for Lazy Writers (justsomecynic; ahbwrites)

How to Write Deep P.O.V.: 8 Tips and Examples (Now Novel)

Character Flaws: Creating Lovable Imperfections (Now Novel)

How to Use Character Flaws to Enrich Your Writing (Perpetual Stories)

Character Flaws: When Is Too Far Too Far? (The Character Therapist)

20 Powerful Romance Tropes (and How to Make Them Original) (Jericho Writers)

Does Your Character Have a Secret? (Writers Helping Writers)

Creating Villain Motivations: Writing Real Adversaries (Now Novel)

Some Quick Character Tips (Coffee Bean Writing)

Dynamic vs. Round Characters: Who Needs a Character Arc? (The Novel Smithy)

Problem #14: The Novel Suffers From Arbitrary Complexity

Solution: More spectacle isn't always better. Larger and relentlessly diverse casts aren't necessarily more dynamic or more representative. More gore doesn't exactly make the violence more believable. More tears won't always pull readers into a deeper emotional connection.

Balance in everything, whether in drawing lots for which characters live or die, or assembling the combination of goals and threats the cast must surmount to reach the end.

Sometimes, it helps to weave from the simple toward the complex: If you understand what is essential to the story, and the role of each character in the story, then you can expand outward, deliberately, and unfold more detail from a central theme or narrative device. (If the author does it the other way around, and weaves from the complex toward the simple, then plot holes form, characters lose their purpose, and the story's conclusion feels less and less tethered to the inciting incident that supposedly pulled in readers at the outset.)

Writing Resources:

5 Ways to Make Mundane Scene More Interesting (Writing Questions Answered)

Feeling Overwhelmed by Plot Points (Writing Questions Answered)

What Is Prewriting? Preparing to Write With Purpose (Now Novel)

How to Write the Perfect Plot (in Two Easy Steps) (Helping Writers Become Authors)

Writing Description: Encourage Readers to Infer More Than They Realize (ahbwrites)

Reasons to Kill Your Characters (Coffee Bean Writing)

How to Absolutely Wreck Your Audience With a Character Death (lunewell)

Coming Up With a Plot (From Scratch) (September C. Fawkes)

Problem #15: The Story Goes Off the Rails in the Third Act

Solution: Weaving a compelling third act necessitates a guarded understanding of how to view and interpret a story on the micro and macro levels. That is to say, an attention to detail is essential, but equally valuable is the opportunity to take a step back and view the whole narrative as the sum of its parts. Do individual characters achieve their personal goals? Are relationship arcs incomplete? Is the drama, humor, or sense of mystery that drove the story in the first two acts, present or validated by the third act?

If one thinks of the whole of a story as a tapestry of sorts, then one might also view each chapter, arc, or act as a meaningful shape, pattern, or attribute of that greater tapestry. These attributes cue the readers as to what facet of story (or character) to focus on, depending on the moment. These attributes can also expose consequential divergences from established narrative designs.

How should readers interpret and process, or otherwise organize, these complex stimuli? For example, an author who purposefully generates tonal proximity between characters or events will ensure emotional continuity from scene to scene or from act to act.

Writing Resources:

5 Ways to Surprise Your Reader (Without It Feeling Like a Trick) (Writer's Digest)

Writing Great Beginnings and Endings (Writing Questions Answered)

How to Pace a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

How to Write Exceptional Endings (September C. Fawkes)

What Is Pacing in Writing? Mastering Pace (Now Novel)

What Is Rising Action? Building to an Epic Climax (Now Novel)

What Is the Dénouement of a Story? Your Guide (With Tips) (Jericho Writers)

How to End a Story Perfectly (Jericho Writers)

Problem #16: The Novel's Questions Are Left Unanswered

Solution: Conflicts require consequences, character arcs require a destination, and unresolved or unanswered questions have their own purpose. But having too many unanswered questions can make a novel's ending feel too foggy, if not outright incomplete. In short, loose threads can be frustrating.

Handled appropriately, loose threads may encourage the reader to hum and ponder how each character's life may evolve following the novel's events. Some readers adore the beauty of an imperfect story. However, handled poorly, loose threads speak to a poorly planned and disorganized narrative for which the writer was mistakenly more invested in drafting a kitschy or vulgar hook than a purposeful climax or dénouement.

Writing Resources:

Guide to Writing an Unreliable Narrator (Writing and Such)

Story Threads: Fixing Rips in Our Story (Writers Helping Writers)

Loose Threads Can Unravel a Novel (All Things Writing)

How to Pace a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

Figuring Out Where to End a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

Feeling Overwhelmed by Plot Points (Writing Questions Answered)

What Is the Dénouement of a Story? Your Guide (With Tips) (Jericho Writers)

How to End a Story Perfectly (Jericho Writers)

Suspense Definition Literature: Tips for Writing Suspense (Jericho Writers)

Problem #17: The Story Is a String of Unrelated Vignettes

Solution: For authors who struggle to coordinate or connect a single, cohesive story, it can be tempting to lean into episodic incidents that are individually intriguing but neglect to pull readers into a larger, more satisfying narrative. Resources about structuring scenes and structuring stories are numerous, but for writers who need to connect the muscle and sinew of their story with intent, learning the basics is often the best: Action and reaction compel reader engagement.

How does a character react to a new, tense, or changing situation? How do these actions or reactions introduce the story to readers or help them explore it? And on a micro level, how do word choice, rhythm, and tone reinforce these facets of the story?

What are the characters' goals? What are the stakes? What burdens complicate (or which advantages elevate) these characters' motivations? What conflicts skew these characters' perceptions of the stakes? What does failure look like? What are the consequences or costs? To the environment (social, political, relational)? How do characters respond to these heightened stakes, to the responsibility of these fresh consequences, to the shifting balance of power in the surrounding context?

Writing Resources:

How to Start a Story That Grips Your Readers (Jericho Writers)

Plotting Tip: One Simple Step to Ensure Our Story Works (Jami Gold)

Episodic vs. Epic: Go Bigger With Your Writing (Writers Helping Writers)

Guide: Filling in the Story Between Known Events (Writing Questions Answered)

What Is a Plot Point? Find and Plan Clear Story Events (Now Novel)

The Parts of a Story: Creating a Cohesive Whole (Now Novel)

8 Foreshadowing Laws: How to Foreshadow Right (Now Novel)

Structuring Satisfying Scenes (September C. Fawkes)

The 5 Commandments of Storytelling According to The Story Grid (September C. Fawkes)

Problem #18: The Plot Unravels Through Convenience/Contrivance

Solution: Many writing workshops and advice columns have opined on this for a reason: Coincidences that get characters into trouble are good, coincidences that get characters out of problems are bad. Resolving issues of perceived relevance between scenes, or events, often requires resolving issues of causality. Contrivances do not serve the reader. A believable and engaging rhythm requires everything to be connected.

What realizations or insights emerge after certain events occur? Does context require readers consume certain types of information before others? How can the story be revised to ensure a natural movement between these events, the information they provide, and characters' reactions to this information?

The degree or intensity of relatedness will vary, depending on the author's narrative style and the presumptive demands of the genre or audience. However, nothing should come easy; the characters (and readers) should earn whatever details they acquire to see the story through to the end.

Writing Resources:

7 Novel-Opening Mistakes That Make Literary Agents (And Readers) Groan (Jericho Writers)

8 Common Pacing Problems (September C. Fawkes)

Cause and Effect: Telling Your Story in the Right Order (Writer's Digest)

Crafting an Effective Plot for Children's Books (Writer's Digest)

8 Foreshadowing Laws: How to Foreshadow Right (Now Novel)

Episodic vs. Epic: Go Bigger With Your Writing (Writers Helping Writers)

Figuring Out Where to End a Story (Writing Questions Answered)

Problem #19: The Story Is Tonally Confused

Solution: What is the novel's general attitude, particularly given the story's descriptive specificity, the characters' emotional latitude, and the atmospheric dynamic of the feelings a specific scene is written to elicit? Tone is an interrelated mix of narrative forms and attributes. Identifying, organizing, and manipulating tone means establishing and controlling these attributes. But a word of caution is often warranted: Mixing and matching and glibly contrasting tone doesn't always come across as clever, to the reader, as the writer might imagine. Consistency and relevance are important.

Authors must know the difference between recognizing a scene's tone and sustaining it such that its rhythm lends the appropriate heft. Word choice matters. Character mood matters. Point of view matters. Scene structure matters. And in the end, disruptions matter, too.

Writing Resources:

How Do You Build a Novel's Tone? (Now Novel)

Suspense Writing: Examples and Devices for Tenser Stories (Now Novel)

Feeling Overwhelmed by Plot Points (Writing Questions Answered)

How to Fix Characters Who Are Too Similar (Writing Questions Answered)

Working Comedy and Romance Into Drama (Writing Questions Answered)

Selecting the Right Sentence Structure for the Right Emotion (September C. Fawkes)

Exactly How to Create and Control Tone (September C. Fawkes; ahbwrites)

#writing#writeblr#novel writing#fiction writing#writing tips#writing problems#writing advice#writing research#writing help#writeprob#style over substance#story is too thin#writing conflict#writing villains#arbitrary complexity#questions are left unanswered#writing female characters#writing description#masterpost#tone#mood#the plot unravels#what are the stakes#purposeful climax#sense of mystery

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Secret/Lies/Reveal

Dark Secret

False Utopia

Town with a Dark Secret

Empire with a Dark Secret

Sadly Mythtaken

Secret Past Catches Up

Cassandra Truth

Secret Test of Character

Secret Relationship (friends? romance? parentage? Secret Student? Secret Lover/Secret Child?

Hidden Purpose Test

Secret Keeper or Secret Secret-Keeper.

False Testimony/Confession/Charges

Anything 'Fake' (Redemption? Object? Reveal? Defector?)

Secret Plan

Hidden Agenda

Secret Mission/Deal

Secret Friendship

Secret Message (like wearing an certain color means something? In code? A page in a book?)

Secret Passage/Path/Room/Door

Secret Society/Hidden Village

Ancient Conspiracy

Map All Along

All Just a Dream

Secret Art

Secret or Hidden Witness

Eavesdropping

Shared Mass Hallucination

Invisible Writing

Masquerade

The Unmasking

Really Royalty Reveal

Unaware Pawn

Bait-and-Switch

Keep in the Dark

Unwitting Muggle Friend

Locked Out of the Loop

It Was with You All Along

A person is tortured to get said information.

A thing they did. A thing they are doing. A thing they were going to do.

You were raised your entire life with a purpose, but of course nobody bothered to tell you.

The secret coul get someone in trouble (a threat?), you could be forced to lie or hide it? The secret you hurt a innocent too as a collateral together with the culprit? Or you? To use you? To kill you? You friend did a bad thing, but you don't want to rat him out? Going as far to cover up for him? Or the secret would cause your friend to do a bad thing? Or put two friends against each other? Your Faction is the one to blame?

Investigation of the Evil Authority's shady corrupted business can get you being named unlawfull or a traitor. You may look very suspicious too.

This can be about a posmortum character, maybe even the reason they died.

Secretly working with each other?

A Bad Thing that happened to you, but you hide. Fear of your loved ones's reactions?

Forced into a Fake Relationship?

Manipulation: To do something to her/him? You involve a person into something without telling her about all of it (plan? conflict?) or lie to get her to do/don't do a thing? So he/she won't run? Or stop them?

Do Anything in Secret (from which characters?) or it Happened and Hide it.

A character begin forced to keep a Secret.

Taken to the Grave

Card up in the Sleeve

About

Origins/Backstory

Heritage/Nature

Existence

Responsable/Involved

Relation/Connection

Identity

Different Reason

Did/Didn't

Denial

Action

Cover Up

Ability/Power

Change of the Plans

A given Information

False Cause

'Normal/Mundane’ characters unaware of their conections with the ‘mystical’ can be used as pawns more easily. Or just someone with unaware secret that a bad person knows.

Maybe its not even about the assunt itself, just the fact they lied and its possible consequences. Or the reaction to the reveal (whose?), or what the finder do with the secret. A lie can lead people to do bad things, especially if told by people they trust.

A secret can cause misunderstanding, can get people blamed, put in danger or saved by it, people can be killed to keep it a secret or after it is revealed, because of the content. The lack of the true and whole information about the situation when making a action can lead to many paths.

For the secret keeper? The uninformed? The actuator? The subject? The object? The finder? The tattler? The liar? The revealer? The victim? What are their Character Archetypes? For me, identifying which characters (can? have to?) exist in a Trope helps organize the plot.

Reveals

Character B has an secret that makes Character A angry. Character B can be or not aware of the secret about themselves.

Character A is told an secret about themselves and has an bad reaction at that, affecting his relationship with Character B.

Character B tells Character A the secret about A, mostly likely different story than the lie B made about it.

The reveal can be about both. Maybe they chose to have different reactions to it. To put more drama, add another trope before/during it, like an Death or Betrayal.

A character makes a reveal about themselves. Or a third party makes the reveal of a secret to their friends.

A reveal about a third person, a group, a place or a object.

A reveal about the group they are in? Maybe one if the friends already know? Maybe they are even part of the secret?

The group you are with can be aware of a secret about you that you don’t know. Or a person you trust hid something that affects you.

If lies and secrets are involved, even more conflict. Maybe its not even bad stuff, the problem itself is that they lied/keep secret and its consequences.

Or the refusal to talk about it even under pressure, or forcing someone to keep a secret

Or reveal or declaration about a person without permission or knowledge.

The reveal mostly can take two paths: a total new information being given (It happened) or the story told different of what really happened (how?)

#writing tropes#tv tropes#secret#reveal#lies#writing#writing ideas#writing plot#writing conflict#writing story#writing tips#unaware#avengers civil war#robert baratheon#ned stark#sawada iemitsu#fake

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

can anyone give me advice on writing messy conflict (conflict that isn’t resolved in a long time) or general bad characters? I have an odd…fear of conflict? Or something like that? I’m not great at accurate character analysis if they’re shitty people haha.

#I suck at writing fr fr I am not good at characters#Not to be…pitiful? I think?#writing help#Writing#writing conflict#writing about conflict

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could I have a random Writing Tip? Thxxxxx

-Azzie

Hey! Ty for the ask, here ya go:

make characters skilled in the art of war_.

Just a suggestion to bring something new to the table and develop character and conflict around war and combat!

This point applies to both antagonists and protagonists, but I prefer giving this skill and knowledge to the opponent. As the name suggests, it’s not of much use if there isn’t any war or physical fighting involved in your story so this bit won't be useful to your writing so just skip ahead if you want, but fun to know anyway! (This part might develop not only the antagonist, but plot conflict)

I've read Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” and will definitely recommend that read for an in-depth understanding of what I'm going to explain (I’m just gonna loosely summarise the first three chapters because I'm lazy). Having the villain display this knowledge shows how intelligent and dangerous they are, especially if you have the typical underdog newbie protagonist - this leaves a lasting effect on the reader and other characters.

(Please don’t sue me for teaching you how to successfully wage war, thanks. For legal reasons this is for writing purposes only)

(Read the book for more detail, there are loads of great points I’m not including to stay concise)

Laying plans:

Thoroughly studying the art of war could be the difference between death or survival. Keep the following 7 points in mind when developing a war plan. Consider not only about your own side but the enemy as well:

Which of the two sovereigns (or just which of the two sides, this works for missions too) is imbued with the moral law? (moral law: trust with their people, so they follow them even when their life is at stake)

Which of the two generals has most ability? (Which side’s leader is more skilled)

With whom lie the advantages of heaven (Season, weather, time) and earth (terrain)?

On which side is discipline most rigorously enforced? (This advocates for more compliance and therefore a higher success rate)

Which army is stronger?

On which side are officers and men more highly trained?

In which army is there greater constancy both in reward and punishment?

With this in mind you can forecast both victory or defeat.

Remember: “All warfare is based on deception”

Trick the opponent

When able to attack, seem unable

When using your forces, seem inactive

When near, make the enemy think you are far

When far, make the enemy think you are near

Waging war:

Do not be hastily stupid and waste resources, strength, and manpower on unplanned urgency-based choices, but lack of decisive speed will give your opponents the upper hand. The following failures can be caused by that:

Hunger

Thirst

Attachment to accumulated loot

Outrage at injustice

Human lives and money are at stake when waging war, and recklessness will cause more harm than good. Make use of all the resources you have. Don’t kill who can help, don’t burn what can be used. Victory cannot be achieved without preparation or organisation. Understand your troops and resources so you do not have to rely on second provisions. Keep track of your troops strengths and states of mind.

Attack stratagems:

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Predict victory when:

If the leader knows as much about the opposition’s troops as he knows about himself and his troops. This knowledge will allow the leader to know when to advance and when to retreat.

If the leader knows the correct use of both small and large forces.

If the leader knows how to forge ranks unified in purpose.

If the leader knows how to be patient when the opposition might struggle to be patient.

If the leader knows that his sovereignty should never interfere with the decisions he is making.

This quote also aligns with the 7 points to consider from before (1. Laying plans).

Mass destructive and prolonged warfare benefits no one, the goal should be to subdue and subsume the enemy. Try to attack the enemy’s strategy or plans or separate the enemy from its allies - attacking the army when there is no alternative. It’s better to catch something whole than destroy it.

The following tips should be kept in mind:

Surround the enemy if your forces significantly outnumber the enemy’s forces.

If you have five times more troops than your enemy, you should attack them. If you have two times more, then you should divide the enemy and fight them that way.

If your enemy outnumbers you, then you should hide. Plus, if they significantly outnumber you, then you should escape.

You need a general who can make his own decisions without people above them interfering.

Basing a characters personality around aspects that benefit them in violence and combat not only serves as an easy base for you to model your characters, this also helps you shape how battle and fight scenes can be carried out in your story

#writing#creative writing#writers block#Writing tips#writers#writers on tumblr#written#writeblr#writing help#writing prompt#writing life#your local sewer rat#writing inspiration#writing characters#anti heroes#character development#writing conflict#writing battles#story writing#sun tzu#the art of war

47 notes

·

View notes