#modern continuing slavery etc

Text

Sam’s blood addiction was so reviled but then he saved the world in part because of it

Sam’s “vices” are so reviled by the narrative Dean, even though Sam’s sacrifice and self-corruption save the world

It’s an eloquent parallel to the concept of the sacred executioner role, really (Dean will do self-corruption with MoC later to stop “a great evil”)

Doing the ugly thing, the reviled thing, the untouchable thing so everyone else can go on about their lives none the wiser and completely unaware of the corrupt underbelly and awful work that keeps it running

Or if they are aware, they can righteously judge it, and then mope about how unfair and ugly it is

#Sam’s vices are so held against him#jack too#America is like this#so much of our riches are built on sin#modern continuing slavery etc#nihilism#sacred executioner#my mom did not accept drug use in her don#or husband#but she volunteered at church for recovering addicts#and talked the talk#because she liked feeling superior and needed#but husband and son and family? were not allowed this#because our job as family is to support her#spn sometimes accidentally stumbles on exactly how is it down here#dean crit#just to be safe#it’s also just dynamics of addiction#family and loved ones are judged differently#because you actually rely on them not just the idea of them#expecting too much of your kids#demanding better of your spouse#the trailer trash way#sighs all around

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

When you tag things “#abolition”, what are you referring to? Abolishing what?

Prisons, generally. Though not just physical walls of formal prisons, but also captivity, carcerality, and carceral thinking. Including migrant detention; national border fences; indentured servitude; inability to move due to, and labor coerced through, debt; de facto imprisonment or isolation of the disabled or medically pathologized; privatization and enclosure of land; categories of “criminality"; etc.

In favor of other, better lives and futures.

Specifically, I am grateful to have learned from the work of these people:

Ruth Wilson Gilmore on “abolition geography”.

Katherine McKittrick on "imaginative geographies"; emotional engagement with place/landscape; legacy of imperialism/slavery in conceptions of physical space and in devaluation of other-than-human lifeforms; escaping enclosure; plantation “afterlives” and how plantation logics continue to thrive in contemporary structures/institutions like cities, prisons, etc.; a “range of rebellions” through collaborative acts, refusal of the dominant order, and subversion through joy and autonomy.

Macarena Gomez-Barris on landscapes as “sacrifice zones”; people condemned to live in resource extraction colonies deemed as acceptable losses; place-making and ecological consciousness; and how “the enclosure, the plantation, the ship, and the prison” are analogous spaces of captivity.

Liat Ben-Moshe on disability; informal institutionalization and incarceration of disabled people through physical limitation, social ostracization, denial of aid, and institutional disavowal; and "letting go of hegemonic knowledge of crime”.

Achille Mbembe on co-existence and care; respect for other-than-human lifeforms; "necropolitics" and bare life/death; African cosmologies; historical evolution of chattel slavery into contemporary institutions through control over food, space, and definitions of life/land; the “explicit kinship between plantation slavery, colonial predation, and contemporary resource extraction” and modern institutions.

Robin Maynard on "generative refusal"; solidarity; shared experiences among homeless, incarcerated, disabled, Indigenous, Black communities; to "build community with" those who you are told to disregard in order "to re-imagine" worlds; envisioning, imagining, and then manifesting those alternative futures which are "already" here and alive.

Leniqueca Welcome on Caribbean world-making; "the apocalyptic temporality" of environmental disasters and the colonial denial of possible "revolutionary futures"; limits of reformism; "infrastructures of liberation at the end of the world."; "abolition is a practice oriented toward the full realization of decolonization, postnationalism, decarceration, and environmental sustainability."

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten on “the undercommons”; fugitivity; dis-order in academia and institutions; and sharing of knowledge.

AM Kanngieser on "deep listening"; “refusal as pedagogy”; and “attunement and attentiveness” in the face of “incomprehensible” and immense “loss of people and ecologies to capitalist brutalities”.

Lisa Lowe on "the intimacies of four continents" and how British politicians and planters feared that official legal abolition of chattel slavery would endanger Caribbean plantation profits, so they devised ways to import South Asian and East Asian laborers.

Ariella Aisha Azoulay on “rehearsals with others’.

Phil Neel on p0lice departments purposely targeting the poor as a way to raise municipal funds; the "suburbanization of poverty" especially in the Great Lakes region; the rise of lucrative "logistics empires" (warehousing, online order delivery, tech industries) at the edges of major urban agglomerations in "progressive" cities like Seattle dependent on "archipelagos" of poverty; and the relationship between job loss, homelessness, gentrification, and these logistics cities.

Alison Mountz on migrant detention; "carceral archipelagoes"; and the “death of asylum”.

Pedro Neves Marques on “one planet with many worlds inside it”; “parallel futures” of Indigenous, Black, disenfranchised communities/cosmologies; and how imperial/nationalist institutions try to foreclose or prevent other possible futures by purposely obscuring or destroying histories, cosmologies, etc.

Peter Redfield on the early twentieth-century French penal colony in tropical Guiana/Guyana; the prison's invocation of racist civilization/savagery mythologies; and its effects on locals.

Iain Chambers on racism of borders; obscured and/or forgotten lives of migrants; and disrupting modernity.

Paulo Tavares on colonial architecture; nationalist myth-making; and erasure of histories of Indigenous dispossession.

Elizabeth Povinelli on "geontopower"; imperial control over "life and death"; how imperial/nationalist formalization of private landownership and commodities relies on rigid definitions of dynamic ecosystems.

Kodwo Eshun on African cosmologies and futures; “the colonial present”; and imperialist/nationalist use of “preemptive” and “predictive” power to control the official storytelling/narrative of history and to destroy alternatives.

Tim Edensor on urban "ghosts" and “industrial ruins”; searching for the “gaps” and “silences” in the official narratives of nations/institutions, to pay attention to the histories, voices, lives obscured in formal accounts.

Megan Ybarra on place-making; "site fights"; solidarity and defiance of migrant detention; and geography of abolition/incarceration.

Sophie Sapp Moore on resistance, marronage, and "forms of counterplantation life"; "plantation worlds" which continue to live in contemporary industrial resource extraction and dispossession.

Deborah Cowen on “infrastructures of empire and resistance”; imperial/nationalist control of place/space; spaces of criminality and "making a life at the edge" of the law; “fugitive infrastructures”.

Elizabeth DeLoughrey on indentured labor; the role of plants, food, and botany in enslaved and fugitive communities; the nineteenth-century British Empire's labor in the South Pacific and Caribbean; the twentieth-century United States mistreatment of the South Pacific; and the role of tropical islands as "laboratories" and isolated open-air prisons for Britain and the US.

Dixa Ramirez D’Oleo on “remaining open to the gifts of the nonhuman” ecosystems; hinterlands and peripheries of empires; attentiveness to hidden landscapes/histories; defying surveillance; and building a world of mutually-flourishing companions.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson on reciprocity; Indigenous pedagogy; abolitionism in Canada; camaraderie; solidarity; and “life-affirming” environmental relationships.

Anand Yang on "forgotten histories of Indian convicts in colonial Southeast Asia" and how the British Empire deported South Asian political prisoners to the region to simultaneously separate activists from their communities while forcing them into labor.

Sylvia Wynter on the “plot”; resisting the plantation; "plantation archipelagos"; and the “revolutionary demand for happiness”.

Pelin Tan on “exiled foods”; food sovereignty; building affirmative care networks in the face of detention, forced migration, and exile; connections between military rule, surveillance, industrial monocrop agriculture, and resource extraction; the “entanglement of solidarity” and ethics of feeding each other.

Avery Gordon on haunting; spectrality; the “death sentence” of being deemed “social waste” and being considered someone “without future”; "refusing" to participate; "escaping hell" and “living apart” by striking, squatting, resisting; cultivating "the many-headed hydra of the revolutionary Black Atlantic"; alternative, utopian, subjugated worldviews; despite attempts to destroy these futures, manifesting these better worlds, imagining them as "already here, alive, present."

Jasbir Puar on disability; debilitation; how the control of fences, borders, movement, and time management constitute conditions of de facto imprisonment; institutional control of illness/health as a weapon to "debilitate" people; how debt and chronic illness doom us to a “slow death”.

Kanwal Hameed and Katie Natanel on "liberation pedagogy"; sharing of knowledge, education, subversion of colonial legacy in universities; "anticolonial feminisms"; and “spaces of solidarity, revolt, retreat, and release”.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating Fictional Holidays

Happy Holidays everyone!

Like mythology or folklore, holidays can add an extra bit of realism and magic to your fictional worlds, and provide for an interesting setting to portray characters, culture, or even family dynamic.

While you can use real world holidays and adapt them to your worlds, you may also want to create your own! Here’s a few things to consider:

1. What does your holiday celebrate?

Typically, holidays come from historical events or events believed to have happened by religious groups. Christmas is the celebration of the birth of Christ. Diwali celebrates the victory of light over darkness, or good’s triumph over evil. Passover celebrates Israelites’ escape from slavery. This would be a great chance to delve into the history of your world, and how it forms and influences communities.

Otherwise (and as well as), holidays can be expressions of important cultural values such as community, hard work, or family. The Day of the Dead (or Dia de los Muertos) is the celebration of honoring passed family members, Labour day is held to honour the struggle for unionization by working people. What does your holiday say about the society or community that created it?

2. How has your holiday adapted?

As much as holiday is entrenched in longstanding tradition, there is no escaping modernization and adaption to contemporary norms. As much as Christmas is a religious holiday at its roots, for many, it’s a celebration of family and gift giving. Rather than being a saint, Santa has become the jolly toy-maker separated from religion entirely.

If your holiday began to celebrate say Harvest season, but in modern times ‘harvest season’ is no longer regularly recognized, how does this society continue to celebrate this holiday? Where does tradition and modern standards intersect?

3. How do people perceive the holiday?

Even joyous, wholesome holidays are going to have haters. Just think of Valentines Day coming around every year—there are people who love it, people who hate it, and people who see it as a superficial excuse to fund capitalism and consumer culture. What do the people of your world believe about the holiday, or what groups/communities are invited or left out?

4. What rituals go into celebrating your holiday?

During Christmas, many families bring in a tree, wrap gifts to put under it, and bake cookies for a secret intruder in the night. A ritual is just a way people honour something—it doesn’t necessarily have to be cultish or ‘evil’. What longstanding rituals go into the celebration of your holiday?

Maybe gifts are exchanged, candles are lit, cards are given out, money is donated, certain foods are given up or certain times limit eating (such as fasting), families gather, parties are held, etc. etc. There are thousands of ways people celebrate what’s important to them. Consider how each family or character in your story might take a slightly different spin on the same rituals.

I hope no matter what or how you celebrate this year, you get time to spend with your loved ones <3

#writing#creative writing#writers#screenwriting#writing community#writing inspiration#books#filmmaking#film#writing advice#holidays#festiveseason#worldbuilding

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Though I adore the dynamic myself, it struck me as odd a few months back that fans were taking a "Monster loved for the first time" approach to Astarion. Part of the allure of a vampire (for me anyway) is the act of transformation; the horror and tragedy of having lost who you were before—including all those everyday, human experiences. There were debates about precisely how old Astarion was when he died and at the same time fans were screaming over him having his first hug, his first real romance, this is the first time someone has helped him without ulterior motives, etc. and I'm going, "How is that possible?" This is an elf who lived a life before being turned, even if it was short compared to what his race would normally experience. Astarion had a family. He had a job! Yet the fandom (and to an extent the game as well) treats Astarion as more of a Phantom-esque character: deemed monstrous from birth and blindsided by the simplest acts of love because he was denied them from the get-go.

Of course, it's easy enough to read everything through the lens of slavery and torture. Sure, Astarion had all this at one point but it's been so long and his life as a vampire has been so unimaginably torturous that it's eclipsed those earlier experiences. I get that... but time as the answer still didn't fully convince me.

Not until I started romancing him and hit this line:

"I... I don't know. I can't remember."

This is in response to asking Astarion what color his eyes were before they turned red. Can we just sit with that for a moment? He doesn't remember the color of his eyes. This line was a game changer for me because I can't even CONCEPTUALIZE that. Mirrors appear to be pretty common in Faerûn—it's not like this is a setting devoid of all modern inventions and Astarion, as a member of the upper class, absolutely would have had access to various ornate mirrors like the one he starts this scene with—so what does it take to make you completely forget such an ingrained bit of knowledge about yourself? 200 years as a dehumanized slave, obviously. Still, my mind continues to trip over the idea. I have blue eyes. That's a fact I've known since I had any real sense of self. If my eyes were to suddenly change tomorrow I can't imagine forgetting that they were originally blue. Even if I'd put it from my mind for an extended period of time I'd expect the very pointed question, "What color were they before?" would fire some old synapses and drag the information back. Obviously none of us have any idea what 200 years would do to a human brain (or, you know, an elf's) but it still feels firmly in the real of impossibility that I could ever completely forget something like that.

Yet Astarion has and this line more than anything else has sold me on his Baby Monster Loved For The First Time characterization, both in-game and in the fandom. He acts like he's never been hugged before? Of course he does! The guy can't remember his eye color and you think he's going to recall any probably-treated-as-casual-and-thus-didn't-solidify-as-significant-memories hugs while alive? When was the last time you were hugged? I'm not sure. I know I HAVE hugged recently but was the last one with family over Thanksgiving? Did I give my friend a brief side-hug before we parted? I'm lucky in that hugs are such a normalized part of my life that I don't give them much thought... which means that if you were to suddenly enslave me and keep me isolated for 200 years, yeah, I'd probably forget what they feel like too. Or that I ever had any at all.

(Self-hatred is going to play hell with memory too. Once you feel like you don't deserve something and it's continually denied to you it's easier to convince yourself you never had it to begin with.)

So yeah, Astarion acts like someone who was always the monster because he has, on a literal canonical level, forgotten what it was like to be anything else. Which just sets his relationship with Tav into such angsty, terrifying focus. Here's someone who has lost his previous identity. He (rightfully) despises the identity Cazador forced on him. Even if he didn't, Astarion is now miles away, the tattered remains of his self threatened by ceremorphosis. He stares into a mirror knowing he'll never see anything, but doing it anyway because he needs to figure out who he is—and that's precisely where most of us would start. What do I look like? What do others see when they see me? Is that the person I want to be?

Then Tav offers to be his mirror, just like they offered to sketch out the poem on his back. How exquisitely horrible for Astarion. He's being given precisely what he wants but he's in NO position to take it. All his sense of self placed in the hands of another? Asking, "Who am I?" and hearing, "I'll tell you. I'll be the keeper of that knowledge"? That's a far more intimate, potentially destructive power than anything else Astarion is looking to get his hands on AND he's trying to manipulate YOU at this point in the story! It just makes me crazy because Astarion is desperate to figure out who he is, but circumstances have ensured that, at this point in time, he needs to put his trust in someone else to begin answering that question... and the one thing he does know about himself is that he's a manipulative, mistrustful rogue who's only out to keep himself safe. Allowing someone else to take the reins with his identity (again) is probably the least safe thing he could possibly think of.

It's this messy tragic loop that yes, Astarion is working to break by the end of the game (depending on your choices) but in Act 1? Goddamn. No wonder he's trying desperately to maintain control of this relationship. No wonder—despite his best efforts—he's still undone by the simplest acts of kindness.

288 notes

·

View notes

Note

Colonialism is a disease

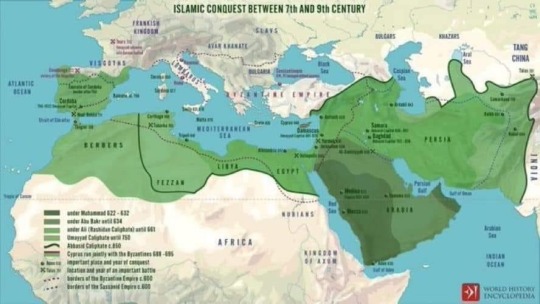

Imagine being an Arab Muslim and having the audacity to call someone else a colonizer. The illustration below is a snapshot of Islamic colonialism and occupation of other people's lands, from the 7th-9th centuries. Islam went on to attack, destroy, occupy and colonize vast swaths of Europe and southeast Asia, as well as what is now called Turkey.

The world has witnessed many colonial empires since the beginning of time. Most notably, the Mongols, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Babylonians, Egyptians, Islam/Ottomans, Portuguese, Dutch, French, Spanish, British, and American. The only empire that didn't take land, even after winning world wars, were the Americans. They actually gave back the Philippines. But I digress.

All of these empires were in large part, created by bloody conquest, and built on the backs of the newly subjugated. The Hebrews were, famously, slaves in Egypt.

No one seems to teach this in the west, focusing more on the Romans, but of all the colonialists, one of the most deadly brutal and expansionist empires were the Muslims aka the Islamists. The Islamic empire expanded by sheer, from Medina (where Muhammad massacred and enslaved the 50% majority Jewish population) all the way into western North Africa, much of Europe, and large populations of Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, parts of India now called Pakistan, etc).

As it expanded using violence and fear, Islam literally took 100 million slaves out of Africa, and was responsible for one of the greatest mass murders in history: killing 10 million (or more) on the forced march from their homelands to the Middle East.

Some examples of Islamic slavery include the Al-Andalus slave trade, the Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Comoros slave trade, the Zanzibar slave trade, the Red Sea slave trade, the Barbary slave trade, the Ottoman slave trade, the Black Sea slave trade, the Bukhara (Uzbekistan) slave trade, and the Khivan slave trade from which Islam took millions of slaves out of Persia to the Islamic khanates. There are Arab/Islamic societies today (Libya, a well-known example) that still trade slaves.

Compare this to Israel. Israel/Judea was never colonial nor expansionist. The Hebrews (aka Jews) were often properties of and were subjugated by, colonial empires, including the Islamic colonial empire.

They Hebrews themselves, as noted above, were most famously slaves of the the colonial Egyptian empire, some 4,000 years ago, before being murdered and subjugated by Islam starting in the 7th century. Somehow able to escape Egyptian tyranny through their own efforts (some say, by the grace of Hashem), the Hebrews settled in their current indigenous homeland 3.600 years ago - a small area by global standards, smaller than Belize, Albania, or Montenegro. They were happy there, and even at their peak, did not attempt to force convert others or expand much beyond their lands.

As historian Barbara Tuchman wrote, Israel is “the only nation in the world that is governing itself in the same territory, under the same name, and with the same religion and same language as it did 3,000 years ago.” Despite all the occupations and forced exiles, the Jews/Hebrews/Israelites have maintained a continuous presence in Judea/Israel/Samaria for some 3,600+ years. And even though Israel was granted modern statehood in 1948, it is one of the oldest continuously maintained countries in the world.

The 'modern' state of Israel came to fruition post WWII, in 1948; the redefinition of borders and modern statehood after the fall of the big colonials was in no way unusual to Israel. Many country's modern borders came to be defined in the post colonial period (post WWI & WWII). While Israel and Lebanon and Iraq and Iran and Syria and Egypt were all ancient civilizations, dating back thousands of years, modern statehood came in the 20th century: For example, statehood was granted to Egypt in 1922; Saudi Arabia and Iraq in 1932; Lebanon in 1943; Indonesia, South Korea & Vietnam in 1945; Syria & Jordan in 1946; India & Pakistan in 1947; Israel, & Myanmar in 1948; Laos, Libya & Bhutan in 1951; Cambodia in 1953; Morocco, Sudan & Tunisia in 1956; Ghana & Malaysia in 1957; and so on.

The problem is, the tribalism and supremacy of Islam, can't stand that it's once-conquered land is now in the hands of the original owners. Islam believes that once it puts a flag in the sand somewhere, it's theirs.

Oh, and by the way, Andalusia (Spain) is next in Islam's sights.

#islam#colonialism#colonialist#colonizers#israel#secular-jew#jewish#judaism#israeli#jerusalem#diaspora#secular jew#secularjew#Islamic jihad#jihad#Hamas#taliban#Isis#Iran#gaza#Samaria#judea#samaria#judea and samaria#jihadis#hamas#hamas war#iran war#islamists

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

as we’re all condemning the Israeli occupation of Gaza and palestine as well as the anti-semitism sweeping the world I really truly hope we remember that all this is because of the imperial West.

This is the work of the colonial powers of the US, UK, France, Russia, Germany etc. When Congolese, Palestinians, Sudanese, Ukrainians are being slaughtered, it is THEM who are benefiting. It is THEM who instigate these atrocities against human beings. It is THEM who start and fund the wars. The West has been the #1 bastion for anti-Semitism (not that anti-semitism is not there in other parts of the world). The Western Empires have killed billions of innocent human beings for wealth. They have harvested nations for CENTURIES. They have massacred countless people for money. It isn’t just stolen wealth, it’s blood money. Their power didn’t end with the slave trade. They are still the biggest human traffickers. They still profit off the labor of ordinary folk in the global south. UNFAIRLY. Colonizers deliberately agitated different ethnic groups within the regions they colonized to encourage instability and discord. The US has been instrumental in modern times when it comes to this strategy of destabilization. Everything that happened in the colonial scramble of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as creating reckless borders that affect inter-ethnic relations to this day, treating their land as play things, is something that has contributed to the situation in Palestine. Just read about the UN’s hand in it. The US is still killing Native Americans today. France is still killing Central Africans today. I am so tired of different genocides gaining traction on social media and people acting like these are all random, isolated incidents that just popped out of the ground. THEY HAVE BEEN HAPPENING FOR DECADES IF NOT CENTURIES. The culprits are always the same.

LOOK AT THEM. EMPIRES BUILT ON MASS SLAVERY AND GENOCIDE WILL NEVER ESCAPE THEIR ROOTS.

THEY MUST CONTINUE TO SUSTAIN THEMSELVES ON THE BLOOD OF INNOCENTS.

THEY MUST BE RESISTED AND DISSOLVED.

#anti us#anti uk#anti Russia#anti france#imperialism#free palestine#free Congo#free Sudan#colonialism#Israel#anti semitism

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this is weird, but you seem particularly approachable about questions and such, and I was kinda curious to ask.

I'm not Jewish, but I consider myself to be an ally and I'm consistently willing to call out BS from other non-Jews, especially lately.

But a number of times over the years, I've seen mixed opinions on whether any criticism of circumcision is inherently antisemitic or not, and I worry that my perspective makes me an unwelcome or ultimately shitty ally.

I have an unwavering principle that non-essential surgery or cosmetic surgeries shouldn't be done on babies, a belief that's rooted in my being intersex. I don't start the argument with people, or start criticizing if it's mentioned, and I certainly don't use it as a gotcha or push my point of view on others.

But if specifically asked, I'll say what I said above, that I don't believe in medically unnecessary procedures on babies much too young to consent.

Is this some deep set antisemitism I need to unpack or reconsider my ideology about before I can consider myself an ally at all?

I dont see how criticism of circumcision is antisemitic tbh, same way I dont see how western countries banning Kosher slaughter is antisemitic. I think the act is barbaric and cruel (applies to Kosher slaughter as well), and just because our ancestors saw the ancient Egyptians do it and thought Nice doesnt mean that we should continue mutilating kids in modernity. There are plenty other bronze age traditions we stopped practicing (stoning, slavery, using barrels of wine to check for virginity, etc) because theyre incompatible with modern liberal values, why should this be any different? I find that religious jews will view these topics as a personal attack on their values/lifestyle which would prompt accusations of antisemitism.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Elijah actually a feminist? Because he said so but his actions..

Elijah Mikaelson is what we would call a "second wave feminist" or a "white feminist." While I don't necessarily subscribe to the ideas of "waves" of feminism, I think it simplifies it enough for this discourse.

Elijah is a feminist in the most basic sense of the term, in the way he believes women can be equal to men and encourages it. However, he does not actively work to dismantle the patriarchy. He is one of those cases where he likely was progressive at one point, however, society has long since progressed past him.

Dealing with the basic understanding of feminism which is basically just believing women can be equal to men, sure Elijah is a feminist. Elijah has always admired strong, independent women, even in societies where that would not be the norm.

I know some people argue that he is not because of his treatment of Katherine, but I would disagree with that. While I do not like that he was willing to sacrifice a young woman for his brother, it wasn't based on her being a woman. You can argue that he should have offered her more protection at that time because of the power dynamic between them, but again, most of the power dynamic came from Katerina being human. It would have played out similarly if the doppelgangers had been men.

I would also add that he seems to be the only one who supports Rebekah's dreams throughout the show and doesn't make sexist comments about her love life. (I'm looking at Kol and Klaus)

By the 21st Century, when the show takes place, thinking women should be able to learn to defend themselves and be equal to men is not enough. He says he is a devout feminist and then follows it up with a decidedly sexist comment. While I do understand this is the joke, it is still a thought he had and then said aloud while acknowledging it is sexist. I believe this is the only blatantly sexist comment he's made, but correct me if I'm wrong.

I wouldn't consider any of the men in this show to be true feminists for modern times. I don't think the writers even understand what that means.

This current wave of feminism focuses on intersectionality and the deconstruction of the hierarchy that has served to oppress women, the patriarchy. The quote from Enola Holmes really sums it up for me.

Elijah, and the rest of the vampires in the show, have the time, money, power, and privilege to affect real change in society, however, none of them do. Instead, they rather throw parties and blow their money, letting life around them happen. Because why change a system that is working for you?

I wouldn't expect any character in the show to understand intersectionality as the writers of the show often express classist and racist ideas/stereotypes. We see Elijah with a woman of color on a plantation that we know people are being enslaved on. Again, all of these vampires lived through times of slavery and none of them lifted a finger to try and end a system of oppression.

So it is not surprising that none of the men in the show lift a finger to help women's rights. We hear Rebekah mention it, but it is quickly followed up by a sexist comment. This is a theme throughout the show with the female characters, they are often judgemental and cruel to each other using terms that are definitely not feminist. But I digress.

Elijah seems to subscribe to the idea of feminism that if a woman can do what a man can do, she should be able to climb to the top of the patriarchy. As we now know, this is not enough. Letting women get involved in the patriarchy doesn't solve anything. It is a system that oppresses all people and needs to be dismantled rather than allowing women to join it.

We see Elijah throughout the show respect many different types of women which shows his ability to grow as a feminist. However, again, his lack of a deeper understanding of how race, class, privilege, etc. play roles in feminism continued to hinder him. We mostly see this in Elijah's more classist view of the world. Elijah is known for being condescending to others, although I do feel like it was mostly reserved for men.

I believe Elijah would be accepting of the LGBTQ+ community but that could just be head-canon.

So while Elijah doesn't do too much that is blatantly sexist, I would not classify him as a feminist by today's standards. I think he would be willing to learn if there was a character in the show that could actually educate anyone on feminism. But first, someone needs to educate the writers. (Which is a plug for my fic because, don't worry, Astra will not let that stand)

#elijah mikealson#feminism#as a devout feminist#tvdu#the originals#tvd#the mikaelsons#the vampire diaries#anon ask

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stories of Beenadick Thundersnatch paying reparations for slavery in Barbados especially because his family was heavily compensated for losing their slaves when slavery was abolished in 1834 is fun and all. (Though inaccurate)

But need I remind you slavery was abolished in America in 1865 and American slave owners were also compensated for their slaves being freed?

Not to mention the freed slaves were promised reparations in the form of land, which never came.

And the lack of resources forces recently freed slaves to continue to work the plantations they were on.

Not to mention Neo-Slavery. Which is a mix of "freed" slaves being put into camps which are essentially the same houses that they were kept in as slaves because the union soldiers didn't know what to do with all of these recently freed people that had no education, no money, no way to care for themselves, etc.

And anti-vagrancy laws that allowed them to be arrested and forced back into slavery because the 13th amendment says "unless punishment for a crime".

Black people continued being kept as slaves as late as 1963 in rural areas because no one caught it and the slaves were so uneducated that they couldn't read whatever knews was sent that they were free.

(Legit. Imagine fighting for desegregation completely unwitting to the fact that slavery was still happening.)

And modern day slavery in the US prison system using that 13th amendment loophole I mentioned earlier.

So maybe instead of applauding at attempts to force Beenadick Slaverbatch to pay reparations. Maybe we should work on ending slavery in the states and working on reparations here, yes?

-fae

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you have any doubts that the phenomenon of Donald Trump was a long time a’coming, you have only to read a piece that Gore Vidal wrote for Esquire magazine in July 1961, when the conservative movement was just beginning and even Barry Goldwater was hardly a glint in Republicans’ eyes.

Vidal’s target was Paul Ryan’s idol, and the idol of so many modern conservatives: the trash novelist and crackpot philosopher Ayn Rand, whom Vidal quotes thusly:

“It was the morality of altruism that undercut America and is now destroying her.

“Capitalism and altruism are incompatible; they are philosophical opposites; they cannot co-exist in the same man or in the same society. Today, the conflict has reached its ultimate climax; the choice is clear-cut: either a new morality of rational self-interest, with its consequence of freedom… or the primordial morality of altruism with its consequences of slavery, etc.

“To love money is to know and love the fact that money is the creation of the best power within you, and your passkey to trade your effort for the effort of the best among men.

“The creed of sacrifice is a morality for the immoral…”

In most quarters, in 1961, this stuff would have been regarded as nearly sociopathic nonsense, but, as Vidal noted, Rand was already gaining adherents: “She has a great attraction for simple people who are puzzled by organized society, who object to paying taxes, who hate the ‘welfare state,’ who feel guilt at the thought of the suffering of others but who would like to harden their hearts.”

Because he was writing at a time when there was still such a thing as right-wing guilt, Vidal couldn’t possibly have foreseen what would happen: Ayn Rand became the guiding spirit of the governing party of the United States. Her values are the values of that party. Vidal couldn’t have foreseen it because he still saw Christianity as a kind of ineluctable force in America, particularly among small-town conservatives, and because Rand’s “philosophy” couldn’t have been more anti-Christian. But, then, Vidal couldn’t have thought so many Christians would abandon Jesus’ teachings so quickly for Rand’s. Hearts hardened.

The transformation and corruption of America’s moral values didn’t happen in the shadows. It happened in plain sight. The Republican Party has been the party of selfishness and the party of punishment for decades now, trashing the basic precepts not only of the Judeo-Christian tradition, but also of humanity generally.

Vidal again: “That it is right to help someone less fortunate is an idea that has figured in most systems of conduct since the beginning of the race.” It is, one could argue, what makes us human. The opposing idea, Rand’s idea, that the less fortunate should be left to suffer, is what endangers our humanity now. I have previously written in this space how conservatism dismantled the concept of truth so it could fill the void with untruth. I called it an epistemological revolution. But conservatism also has dismantled traditional morality so it could fill that void. I call that a moral revolution.

To identify what’s wrong with conservatism and Republicanism — and now with so much of America as we are about to enter the Trump era — you don’t need high-blown theories or deep sociological analysis or surveys. The answer is as simple as it is sad: There is no kindness in them.

(continue reading)

#politics#republicans#capitalism#ayn rand#libertarians#calvinism#kindness#selfishness#greed#donald trump#conservatism#neoliberalism#the cruelty is the point#reaganism#white america#gore vidal#ayn randroids

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok, Ayn Rands in the comments. A is A. What an argument. I don’t see what’s there to be confused about my ask. I’m responding to the idea that you have perpetuated that anyone who engaged in these practices is inherently and undeniably evil.

Separately, the morality of rape as a practice, viewed universally, is far different than assessing an individual's moral worth, which is inherently contextual.

There mere fact that someone engages in a practice you deem immoral, does not make them inherently evil. That's kind of the point of the show.

If society collectively accepts a problematic practice, it's far more difficult to individually fault a person for succumbing to that societal pressure and the associated negative consequences.

For instance, a farmer trying to make a living in a slave economy absent slaves, will be at an impossible competitive disadvantage.

He will not have the capital to run his farm. It's unlikely he will be able to even subsist. Whether someone lives or die, their entire quality of life, and their profession, could hinge on whether they owned slaves.

This is a similar argument to people who say “Rape is rape, regardless of legality, the morality of it was wrong then as it is wrong now.”

(1) First, "rape" quite literally isn't "rape" when comparing historical periods because there were completely different definitions of rape, which was my entire point.

Words change.

What we considered rape now, wasn't considered rape back then.

Even in the last 15 years, the definition of rape has dramatically changed both in common linguistics and legally.

IN the 1980s, rape was more narrowly defined as violent, forced penetrative sex.

We now live in a world where failure to affirmatively get verbal consent before engaging in non-violent, unforced sex, is considered rape.

These terms are constantly evolving. Your definition of "rape"--and countless other words--will undoubtedly change over the remainder of human history.

Future generations will look at some of your beliefs as barbaric, no matter how morally certain you are of their worth now. Including practices you may have taken part in. Does this make you evil?

Yes, undeniably slavery is bad. In the modern economic landscape, a lot of people will argue that the free market driven Capitalist system is just employing slavery with extra steps.

But, if you want to be rationally historical, slavery was an institution practiced by not only by one culture, but EVERYONE, commited on EVERYONE regardless of race/gender/nation etc. During the viking times, it is either you win over your enemies and take them as slaves (lest they go back and bring more people to take your people out, and of course as farm hands and more labor) OR get enslaved yourself and your loved ones. It was barely a choice, you were thrust into it by the conditions of warfare and survival. Some became "successful" and get this institution passed down to their children, who don't excatly know what to do with what they were born with except continue it as they are trained to.

No one should justify slavery, and yet it is easy to villify history seen through modern standards. I wouldn't know what exactly to do in such a scenario myself. The most righteous ways are either, try to be a harmless slave owner, or actively fight against the institution then you n your family get slaughtered by the king, or kill yourself from the get-go so you don't have to deal with society and it's problems at all!

Reducing people's inherent moral worth into binary "good" and "evil" is already an obnoxious and narcissistic practice on its own.

Reducing that moral worth on the sole grounds of whether they owned slaves--an accepted practice in many cultures in human history--is so god damn simplistic.

I am comfortable calling slavery a "bad" practice." I am uncomfortable saying every single person who owned slaves throughout human history is inherently evil on that sole basis.

What a comfortable, naive, and privilege position you have, as you sit in judgment from your sofa, looking backwards 1000 years.

Back then, entire economies were built around slavery. The choice of whether to own slaves, was a choice of whether to survive or to starve to death.

The world was a far more desperate and dangerous place.

When people refuse to hold any kind of nuanced judgements, you enter into a conversation where no matter what another says there will never be an understanding. A step above that is holding extreme viewpoints.

Is slavery bad? No shit. Are there shades of gray? Absolutely. Refusing to acknowledge that is forgoing nuance and acceptance of reality. Not everything is pure black and white.

It's all just an extension of these posters' own moral narcissism (ironically).

The subtext here is that they all view themselves as amazing people. The logical implication of their argument is that 99.9999999999999999% of all humans living before them were shittier people than they are.

How convenient a world view that everyone who lived before "you" is inferior to you, simply by virtue of their participation in antiquated (but accepted-at-the-time) societal practices, while you sit in judgment from your couch.

These naive, narcissistic fools, all pretend they would be "better" people if they were magically born into those same historical eras.

the world is not drawn in absolute moral binaries. Yet, the vast majority of you draw people in absolute moral binaries, e.g., "everyone who supported or practiced “rape” or slavery is inherently evil."

No one is saying that Slavery is good. It's bad. I'm not excusing slavery.

I'm simply suggesting that historical circumstance--just like mens rea--has a role in assessing morality.

People are products of their time and place. I have a hard time calling someone "evil" merely because they engaged in some antiquated practice, which was difficult NOT to engage in (or else suffer terrible consequences).

It's also a spectrum. Someone might own slaves, but not beat their slaves. And slavery varied by country and time. I feel like people are automatically treating all historical slavery as if it is American slavery.

Slaves in Roman times could be extremely educated and live fairly comfortable lives, in the case of Greek slaves. Romans would often use Greek slaves for administrative purposes rather than manual labor (e.g., Greek Slaves would read and write letters for their masters whose vision was failing).

That kind of slavery is far less brutal than, e.g., American slavery, where you are keeping people in cages, and working them to death.

When the only realistic option in a feudal society is being a slave-owning noble or merchant, or a impoverished serf who dies at age 30 from starvation, I'm far more sympathetic to people engaging in a bad practice.

hey did you know you can make your own blog

#imma keep it real with you chief… nobody will read all that#i didnt#ask#i still dont know what post triggered this manifesto#its kind of funny though this goes in the gallery#shit talking

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having examined marriage, Engels turns his attention to the patriarchal family, as precious to the Victorians as it later became to conservative sociology in the period of reaction. In Engels' tart phrase, the family's "essential points are the assimilation of the unfree element and the paternal authority." "It is founded on male supremacy for the pronounced purpose of breeding children of indisputable paternal lineage. The latter is required because these children shall later on inherit the fortune of their father." Despite the decline of inherited wealth, this is still so; legitimacy is quite as important now, and thought to justify the cost and education of rearing the young in the nuclear family.

The ideal type of the patriarchal family and the ancestor of our own is the Roman family, whence come both the term and the legal forms and precedents used in the West. Originally, the word familia did not, Engels cheerfully informs us

“. . . signify the composite ideal of sentimentality and domestic strife in the present day philistine mind. Among the Romans it did not even apply in the beginning to the leading couple and its children, but to the slaves alone. Famulus means domestic slave, and familia is the aggregate number of slaves belonging to one man . . . The expression [familia] was invented by the Romans in order to designate a new social organism the head of which had a wife, children and a number of slaves under his paternal authority and according to Roman law, the right of life and death over all of them.”

To this, Engels adds Marx's observation that

“the word is, therefore, not older than the ironclad family system of the Latin tribes, which arose after the introduction of agriculture and of lawful slavery . . . The modern family contains the germ not only of slavery (servitus) but also of serfdom. . . It comprises in miniature all those contrasts that later on develop more broadly in society and the state.”

In noting its economic character Engels is calling attention to the fact that the family is actually a financial unit, something which his contemporaries, like our own, prefer to ignore. Due to the nature of its origins, the family is committed to the idea of property in persons and in goods. "Monogamy was the first form of the family not founded on natural but on economic conditions, viz. the victory of private property over primitive and natural collectivism."

Whatever the value of Engels' insistence on the priority of a "primitive and natural collectivism," the cohesion of the patriarchal family and the authority of its head have consistently relied (and continue to do so) on the economic dependence of its members. Its stability and its efficiency also rely upon its ability to divide its members by hierarchical roles and maintain them in such through innumerable forms of coercion—social, religious, legal, ideological, etc. As Engels makes clear, such a collection of persons cannot be said to be free agents. Historically, nearly the entire basis of their association is not affection but constraint: much of it remains so.

-Kate Millett, Sexual Politics

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Black Mermaids, Miles Morales, and Black Horror - Oh My!

For Black folks, the summer movie season started off great. First The Little Mermaid opened and folks all over were "wanting to be a part of her world." A week later Spiderman: Across the Spider-verse was released and again, folks lost their minds. (It's been 2 weeks since I've seen it and I'm STILL thinking about it). For the adults, The Blackening comes out just in time for Juneteenth and is a mix of comedy & horror. I saw the original short film it was based on (which was hilarious) so I'm excited to go see it this weekend. Thinking about these movies led me to think about books with similar themes/characters, etc. that I also enjoyed. So...if you liked any of those movies, here are similar books with Black leads for you to read.

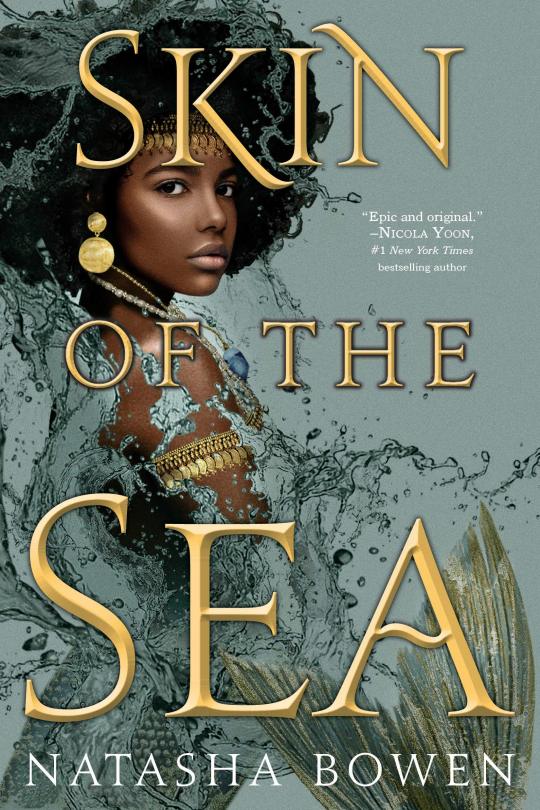

If you liked The Little Mermaid, check out this new duology...

Skin of the Sea by Natasha Bowen

A way to survive.

A way to serve.

A way to save.

Simi prayed to the gods, once. Now she serves them as Mami Wata--a mermaid--collecting the souls of those who die at sea and blessing their journeys back home.

But when a living boy is thrown overboard, Simi goes against an ancient decree and does the unthinkable--she saves his life. And punishment awaits those who dare to defy the gods.

To protect the other Mami Wata, Simi must journey to the Supreme Creator to make amends. But all is not as it seems. There's the boy she rescued, who knows more than he should. And something is shadowing Simi, something that would rather see her fail . . .

Danger lurks at every turn, and as Simi draws closer, she must brave vengeful gods, treacherous lands, and legendary creatures

If you want more of Miles Morales's Spiderman adventures....

Miles Morales: Spider-Man by Jason Reynolds

Miles Morales is just your average teenager. Dinner every Sunday with his parents, chilling out playing old-school video games with his best friend, Ganke, crushing on brainy, beautiful poet Alicia. He’s even got a scholarship spot at the prestigious Brooklyn Visions Academy. Oh yeah, and he’s Spider Man.

But lately, Miles’s spidey-sense has been on the fritz. When a misunderstanding leads to his suspension from school, Miles begins to question his abilities. After all, his dad and uncle were Brooklyn jack-boys with criminal records. Maybe kids like Miles aren’t meant to be superheroes. Maybe Miles should take his dad’s advice and focus on saving himself.

As Miles tries to get his school life back on track, he can’t shake the vivid nightmares that continue to haunt him. Nor can he avoid the relentless buzz of his spidey-sense every day in history class, amidst his teacher’s lectures on the historical "benefits" of slavery and the modern-day prison system. But after his scholarship is threatened, Miles uncovers a chilling plot, one that puts his friends, his neighborhood, and himself at risk.

It’s time for Miles to suit up.

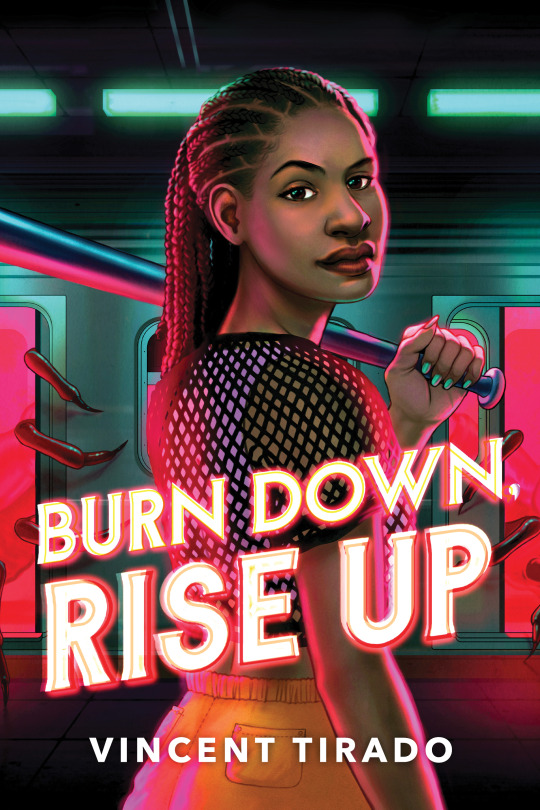

If you are ready for some summer horror, check out...

Burn Down, Rise Up by Vincent Tirado

Mysterious disappearances.

An urban legend rumored to be responsible.

And one group of teens determined to save their city at any cost.

For over a year, the Bronx has been plagued by sudden disappearances that no one can explain. Sixteen-year-old Raquel does her best to ignore it. After all, the police only look for the white kids. But when her crush Charlize's cousin goes missing, Raquel starts to pay attention—especially when her own mom comes down with a mysterious illness that seems linked to the disappearances.

Raquel and Charlize team up to investigate, but they soon discover that everything is tied to a terrifying urban legend called the Echo Game. The game is rumored to trap people in a sinister world underneath the city, and the rules are based on a particularly dark chapter in New York's past. And if the friends want to save their home and everyone they love, they will have to play the game and destroy the evil at its heart—or die trying.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I heard this, but couldn't find any source for it: is it true that capitalism is rooted/based on slavery, and that's why the prison system uses the unpaid labor of prisoners to do things and why many "essential workers" get ow pay? Because capitalism wasn't designed to function with everyone being viewed and paid as people?

Yes. The modern system of capitalism, as developed from the late 18th century onward, was never designed to function for the benefit of and in recognition of the personhood of all people. Indeed, quite the opposite. The invention of the cotton gin in 1791, the machine that quickly and easily separated seeds from the cotton plant (previously, they had to be laboriously and time-consumingly picked out by hand), is often cited as the beginning of the age of industrialization, which exploded exponentially in the 19th century in both Britain and America (and elsewhere, but for the purposes of this analysis, we will be focusing on those two). Slavery was outlawed in mainland Britain in 1774, but continued in its overseas colonies until the early 19th century and the efforts of William Wilberforce to put a stop to the transatlantic trade (which was how the British Empire had amassed a vast portion of its land, holdings, and wealth). Thus, they had to hastily find a replacement for that workforce, and that gave rise to the conditions of the early Industrial Revolution, wherein almost every working-class British citizen, regardless of age or infirmity, was expected to labor in factories for upwards of 10 hours a day for very little pay and in oftentimes horrendously unsafe conditions. This is when Britain experienced its fiercest labor wars (often, yes, literal wars between workers and bosses) and organized legal drives to outlaw child labor and establish basic standards of health and safety.

The history of capitalism unfolded somewhat differently in America, where slavery remained legal until 1863 in theory and did not fully begin to disband as an organized economic system until after 1865 and the end of the Civil War. Even then, recently emancipated slaves remained so hugely disadvantaged that they had to build their wealth from scratch, and this period saw en masse Black migrations to industrial northern cities such as Detroit, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. But American workers of all races -- white, Black, Chinese, European immigrants, etc etc. -- were likewise forced to physically (and violently) fight for their rights. The history of 19th-century labor relations is littered with bloody strikes, violent uprisings (such as the 1877 Great Upheaval) and other militant workers' movements that constantly pushed back on the bosses (who in the late 19th century were often the "robber barons" who saw nothing wrong with making as much money as fast as possible and with likewise very little regard for the lives and health of their workers). Capitalism was initially designed and carried out as a brutally inhuman system designed to enrich the societal and economic elites as fast as possible, and the only reason it was modified to take anyone else into consideration at all was because workers fought back en masse. And that is because, as noted, it had its essential roots in slavery and the British and American elites' systemic expectation that they could reap massive economic gains without having to pay anything to their enslaved workforce or redistribute their own wealth in any way. Once that was dismantled, they ferociously resisted having to do so, until they were forced.

Twentieth-century socialist economic theory and political movements modified this somewhat, and the previously discussed high taxation rates in postwar America, especially under Eisenhower and his successors, helped to redistribute wealth in substantial and impactful ways. Starting in 1980, that was then all rolled back under Reagan, and an unreconstructed 19th-century robber-baron policy of massively enriching those at the top, at the direct expense of those at the bottom, was returned to primacy in American and Western economic doctrine. (If you want to learn how the "gospel of the free market" was disastrously exported into other countries as part of American military and cultural imperialism, read The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein.) But yes; the only reason capitalism has ever granted any rights or accommodations to the working class was because it was forced to do so. Karl Marx already had it dead to rights when he published The Communist Manifesto in 1848, where he developed his theories of the bourgeoise and the proletariat wherein the former exploits the latter at outrageously unequal balances of power and profit, and called for the proletariat to actively and fiercely resist this exploitation.

Of course, Marxism has since become a byword for all kinds of pseudo-leftist political movements and philosophies that are only tangentially related to Marx's original work (or indeed, make any sense at all), but at the point of its appearance in the mid-19th century, capitalism was functioning, indeed, largely the same way it functions today. That was why his ideas found such an eager audience and inspired the latter half of the 19th century and its associated workers' rights movements. But anyway, yes. Even a cursory glance at 19th-century history of labor, and how the working class had to fight tooth and nail to even get to the badly flawed system that we have now, is both depressing and illuminating.

#anonymous#ask#history#history of capitalism#history of labor#history of racism#american history#british history

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sooo I was a thinking

in the shower nonetheless

I remember a conversation I held with @d4rkpluto and a couple of other folks about Planetary Rules in terms of different races. I'll be honest its not the first time I've heard of that concept, I just know different folks have different interpretations.

So I just wanted to expand on one I heard about Saturn ruling over Black people and my personal thoughts about it.

..........

If anyone knows Black people (pretty sure everyone on here should, its the internet), we struggle and prevail (and struggle yet again). That's been our history for literal centuries (millenniums depending on where you talking about). There's the Trans Atlantic slave trade, Jim Crow, the caste systems of Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France and America and much more in the Western hemisphere. There's the Arab slave trade (fun fact almost all of Asia is guilty of participating), colonization and neo colonization of Africa, Australia, the Philippines (and more, modern day slavery, xenophobia against Africans+ other Black folks, the displacement and systematic destruction of Melanesian societies and people in the Eastern hemisphere.

The story of struggle is not new to Black people on a global stance. What also is not new is the prevailing/ survival of Black folks either.

We have AAVE, Patios, Creole and various other Black dialects (languages if we'll be honest), Samba, Rap/Hip Hop, Hood culture (Favela etc also apply), Country, Rock, Story telling, and hairstyles in the West. The forming of the African Union, reconnection of Aboriginal people to their lands (we gotta talk about that more), the acknowledgment of Melanesian groups in South and Southeast Asia (as well as the Pacific), and new cultural revivals in the East.

All in all tragedies are used not as an end all be all but a method to spark change. Change of the things that are able to be controlled. It made something new out of something old with what was had.

What the hell does that have to do with Saturn???

Saturn is one of the strictest teachers there is. If you don't get a lesson, you'll just be faced with it again in a different form. You can try to avoid it and it will force you to adapt to circumstances you can't control by controlling what you can.

Saturn frankly can be seen as a hidden blessing because you learn to let go of what can't be controlled outside of you. To be a change that sparks change in others and not let what currently is stifling you end you.

I'll be honest Black people definitely fit that whole criteria. We as a global collective have gone through so much shit. We continue to go through so much shit, and yet we always come up on top.

I would also say some key themes of both Saturn and Capricorn can easily be pointed out in any Black person or culture.

What are those themes?

I'd like to start off with money since we all love talking about it.

From my perspective Black people do not hold generational wealth. Especially not in the same sense as other folks. You can point out any rich Black person and I promise you go back a generation or two they didn't have that same standing, go forward a generation or two the same applies.

Why is that?

There are (global) systematic things that prevent Black people from raising from the bottom of the socio-economic to even the middle or top. In all honesty every society has at least one thing in place that prevent it due to some "balance" wanting to be kept. In the US you have things like redlining/gentrification, in all the of Latin American countries you have the caste system (la casta) (its anti Black (and Indigenous), ask Black Latinos), in South Asia there's also the caste system (I don't even wanna get into this) West asia still holding on to stereotypes + slavery, Europe... Racism and xenophobia (also slavery), South East Asia also has a caste system and the Pacific Islands (+Australia) have anti Black policies and colonial rooted issues.

These things are all in place that limit the amount of land, money, food and even shelter Black folks can global have. If you are highly focused on survival you not going to be focused on saving money. Which is another reason why generational wealth doesn't exist, there's a need to spend money before its gone.

That's a very Capricornian trait. You understand that money equals respect (and for Black people more than just surviving), so the more you have to freely spend the more respected you are. So sometimes you spend it all in the need of respect rather than the need of security.

Since I mentioned security you already know that was about to be the next topic.

Are Black people safe anywhere?

No. Don't mention Africa or other predominantly Black countries either, neocolonialism is an issue.

Black people haven't had security for a very long time. We just make do with what we have and as my dad says "keep it pushin". There's an understanding that most things are out of our control (because everyone knows that antiBlackness would've been gone yesterday). We have to just understand what we have or do individually is what we can do. "It is what it is" pretty much.

Anytime you see a sense of security in a Black community, you will also see some new problem (complete out of our control) pop up. I'll use Jim Crow and sharecropping as an example:

When Black folks (African Americans) were freed from slavery, we didn't have much of anything to our names beside our culture. We were able to find certain jobs and once it was seen that we could thrive off of them, that was quickly replaced by sharecropping. For those who don't know what that is, its being "lended" some land to farm on, however the rent, type of land and prices you could sell your crops for was outrageously different. So Black people farmed, could starting gaining traction, a white (or NonBlack in general) landowner/shop owner/law maker etc wouldn't like that and pretty much screw the Black person over until they were indebted to them. Then the Black family eventually lost their farm (which ties into generational wealth) and had to seek out another source of income.

Some folks turned to railroad work, some went North, some left the US completely. All in all there was a huge factor uncontrollable by Black people that pushed them to adopt, change, and make do with current circumstances.

Saturn's lesson

Saturn has taught me, to never conform. Especially not my language(s) to make another comfortable. Its taught me that people will be uncomfortable with me, and that's okay as long as I'm comfortable with me. Its taught me that security (in a material sense) doesn't and never will last because something I can't control will change it, its how I cope with the change that happens.

That's a lesson all Black people are born knowing and die passing on. That we aren't meant to struggle, we are meant to adapt, thrive, fall and do it again.

Saturn isn't bullying anyone (especially Black folks), its showing us we are truly thrivers who can create out of seemingly nothing. That we will also overcome. That we are always blessed someway.

Plus I think its pretty cool or rains diamonds on some of Saturn's moons and has a ring around it (kinda like how various Black cultures popped from absolutely outrageous circumstances).

If you read this long ass post, thank you. If you would like me to talk about other groups and how I think certain planets rule them, ask below :)

And Black lives always will, and always have mattered

(If you learned something new or would just like to support me you can leave a wittle tip via the tip button or one of the links in my bio. Ko-fi: nymphdreams 🧸)

#astro tumblr#astrology#astroblr#astro notes#astrology observations#astro observations#astrology tumblr#nymph hums#nymph writes astrology#nymph spits#capricorn#planetary rulership#astrology and sociology#saturn#saturn ruled#black tumblr

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

As someone who works with highschool students, around 15/16 years of age, I've come across a conundrum when it comes to books. Just a disclaimer, I'm not an educator.

So one of the kids at work is reading 2 books for their class, the Kite Runner and Kindred. Kite Runner is written by Khalid Housseini and is a critique of the western ignorance of Afghanistan, Afghanistan's ethnic castes between the Pashtun and Hazara, the class divide in Afghanistan, American racism and capitalist hell, and the Afghani problem with pedophile warlords. The Kindred is by a black woman author named Octavia E Butler, and it is about modern day race relations, the depth of hopelessness and trash treatment slaves were subject to, even free ones, what it really means to be a black woman in the 70s and 1840s, racial ignorance, etc etc

So we were chatting and this kid and their friends, and even a few of my peers, remarked on how there was a lot of sexual violence in these two books and that they weren't good reading material either way, which made me kinda side eye them

Housseini writes a compelling narrative from the point of view of the antagonist. This boy ruins his friend's life on the lines of everything I mentioned about the book above to the point that 40 years later, his friend's son is feeling the consequences of it. It's literally one of the easiest to understand ways to present dark but real world topics to kids aged 15/16. It's not even graphic at all except for one part where the son is made to dance suggestively (which is a real practice to sexually exploit young boys in Afghanistan by military lords called Bacha Bazi) and even then it lasts a page if not less.

There's something similar in the Kindred, because the main character and most reoccurring women have experienced some form of sexual violence due to being black women in a deeply racist time among people who view them as barely subhuman. It's still used skillfully, the main antagonist is painted as the nicest he could possibly be under the circumstances and he truly thinks that by tying this woman to him, he could improve her life. He is a white man who owns a plantation and comes from money, and in his eyes he is being extremely generous by offering to marry the woman and free her from slavery. It's like what one of them founding fathers did to that one girl. Aside from that, the MC experiences sexual violence due to her being a black woman, viewed as a slave, who was nearly taken advantage of by the slave patrol who simply wanted to torture her because they could. Again it is commentary on the then and now, as black women continue to be the main targets of assault and sexual violation in America.

And again, it is not gratuitous or graphic, even less so than the original book. In fact, Butler has written more graphic rape in a different book called Parable of the Sower

It did not escape my notice that almost everyone complaining about these instances were white, if that matters.

I just don't know how to articulate the large misunderstanding happening without them immediately writing me off as some kind of pedophile apologist or someone who thinks sexual violence in books is okay. Their teacher is not the best at explaining why these books are important so they've already written them off as a bad teaching decision, but I really want to get across the importance here. It's made even harder by the fact that these kids don't even tend to read the damn books, they just copy off their friends! Do you have any advice for how to broach this topic in an easy to understand way?

--

I don't think you're going to succeed here. These kids clearly aren't getting any kind of good intellectual support anywhere in their lives, and they aren't ready for these kinds of books.

To be honest, I went to schools that foisted very dark and far too adult books on us from age 10 on, and I too did not really get why at the time. By high school, I was more ready, but it wasn't because I'd been exposed to stuff I hated as a kid. It was more a product of reading a lot and growing up in a household that discussed media intelligently.

I suspect a far more useful approach would be to get them into books that touch on heavy topics but that are overall funnier and easier to digest.

A great literature teacher might be able to make these particular books work for these particular kids even without a gentle introduction to more nuanced and heavier literature over time, but if their teacher isn't like that, you aren't going to be able to make up for it.

Maybe somebody else will have some ideas.

77 notes

·

View notes