#which by all accounts accords with historical fact

Text

The charge that the United Nations is failing to listen to Israeli women elides the fact that, to date, no women have testified publicly about experiencing sexual violence. As Israeli advocates have correctly insisted, this doesn’t mean sexual violence did not occur. Many of the victims of violence on October 7 are dead and will never be able to tell their stories in their own voices, and others may not speak publicly for years, if ever. However, we do not honor the voices of those who may have experienced sexual violence by ventriloquizing them or claiming to speak on their behalf. This is especially true in a context where independent investigations are being intentionally frustrated, and where it is not at all obvious that victims of violence on Oct 7 desire a war of vengeance. As Israeli hostages being held in Gaza continue to die from violence there, many of their families are calling for a ceasefire.

Historically, women have not only been silenced or disbelieved about sexual violence. They have also been spoken for and instrumentalized, particularly in conflict situations. For example, in 2011, claims that Viagra had been distributed to Mohammar Gaddafi’s soldiers to encourage mass rape were widely circulated, including by the then-United States Ambassador to the United Nations and ICC Prosecutor, despite an acknowledged lack of victim testimony verifying the claims. These rumours provided essential context within which Security Council support for military intervention was generated. They were subsequently debunked, with an International Commission of Inquiry finding claims of an overall policy of sexual violence against civilians unsubstantiated, but only after the war was complete.

‘Believe Women’ does not, and cannot, mean ‘Believe the IDF’, the Israeli police or security force, or even those who claim to be feminist advocates. As Judith Levine has suggested, the actual victims of violence on October 7 ‘are disappearing into propaganda, becoming talking points to legitimize the pain of other women, children, and men in the killing field on the other side of the fence.’ The dangers of propaganda are particularly pressing in a conflict that has already seen eyewitness testimony of atrocities, such as the beheading of over forty babies, being withdrawn only after being widely circulated and even repeated by United States President Joe Biden.

In contrast to calls for swift condemnation and authoritative statements of what happened, proper investigations that allow victims time and space to speak with adequate material support and protections take time and are almost impossible in conditions of active conflict. In the former Yugoslavia, for instance, the investigation conducted by a Commission of Experts took years and could only begin once peace was established. By refusing to cease hostilities and allow an independent investigation conducted in accordance with international standards of fairness, Israel is prioritising shielding itself from accountability for its own actions in Gaza. As a result, Israel is deferring and potentially denying its opportunity for justice and accountability as well as the opportunity for victims’ voices to be heard on the international stage.

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consulting the convoluted history of supernatural foxes, or why is Tsukasa like that

I know I said you should only expect one long Touhou-themed research article per month, and that the next one will be focused on Ten Desires, but due to unforeseen circumstances a bonus one jumped into the queue. For this reason, you will unexpectedly have the opportunity to learn more about the historical and religious context of the belief in kuda-gitsune, or “tube foxes”, as well as their various forerunners. Tsukasa is clearly topical thanks to Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost, and I basically skipped covering Unconnected Marketeers in 2021 save for pointing out some banal tidbits, so I hope this is a welcome surprise.

The post contains spoilers for the new game, obviously.

Obviously, in order to properly cover the kuda-gitsune, it is necessary to start with a short history of foxes in Japanese culture through history, especially in esoteric Buddhism.

Early history: the Chinese background

Early Japanese sources pertaining to foxes show strong Chinese influence. There was an extensive preexisting system of fox beliefs to draw from in continental literature, dating back at least to the Han dynasty (note that while the well known story of Daji is set much earlier, its modern form only really goes back to the Song dynasty). This is way too complex of a topic to discuss here in full, sadly, so I will limit myself to the particularly interesting tidbits.

A multi-tailed fox in the classic Chinese encyclopedia Gujin Tushu Jicheng (wikimedia commons)

It will suffice to say that historically the fox was perceived in China as a liminal being, and could be associated with pursuits regarded as ethically dubious, ranging from theft and banditry to instigating rebellions and promoting divisive religious views (so, for example during the reigns of firmly pro-Taoist emperors, Buddhist monks could be associated with foxes). Literary texts focused on supernatural foxes emphasized their shapeshifting abilities. In contrast with some of the other well attested supernatural beings in Chinese tradition, they could take a range of human forms, appearing as men and women of virtually any age. Often they favored mimicking people who lived on the margins of society, like bandits, courtesans or migrant laborers. It was also emphasized that they displayed a considerable degree of disregard for authority. The fact these animals lived essentially alongside humans without being domesticated definitely played a role in the formation of this image.

A contemporary statue of Bixia, a deity in the past associated with fox beliefs (wikimedia commons)

At the same time, foxes enjoyed a degree of popularity as objects of semi-official cult, still practiced here and there in China in modern times, for example in Boluo in Shaanxi. The religious role of foxes was reflected in, among other things, the development of terms like hushen (狐神) “fox deity”, or huxian (狐仙), “fox immortal”. The belief in such “celestial foxes” (tianhu, 天狐) was relatively common, and there is even a legend according to which there was a formalized way for the animals to transcend to higher states of existence, with the goddess Bixia making them undergo the supernatural fox version of the well known imperial examinations. If they failed they were condemned to live as “wild foxes” (yehu, 野狐) with no hope of transcendence. There are also accounts of foxes pursuing the status of a xian through illicit means, through a combination of praying to the Big Dipper and draining people’s energy, as documented by He Xiu in the 1700s. Note foxes were already portrayed as worshiping the Big Dipper during the reign of the Tang dynasty, but back then it was only believed this let them transform into humans.

The ambiguity of foxes is evident in the Japanese perception of these animals too. Supernatural foxes are probably among the best known youkai, and especially considering this is a post about Touhou I do not think the basics need to be discussed in much detail. They were believed to shapeshift and to steal vital energy, much like in China. Their positive role as messengers of Inari, a kami associated with agriculture, is generally well known too.

The earliest sources documenting encounters with supernatural foxes are obviously, as expected, the earliest chronicles like the Nihon Shoki, where they mostly appear as omens. By the Heian period these animals are well established in the written record. For instance, Nakatomi Harae Kunge includes “evil magic due to heavenly and earthly foxes” among phenomena which require ritual purification. In addition to the tales imported from China being in circulation, some setsuwa written in Japan involved shape shifting foxes. However, supernatural foxes only gained greater prominence in the Japanese middle ages due to the growth of relevance of two deities they were associated with, Inari and Dakiniten. The latter is more relevant to the topic of this article.

Foxes, Dakiniten and tengu

Part of a hanging scroll depicting Dakiniten riding on a fox (wikimedia commons, via MET; cropped for the ease of viewing)

The connection between foxes and Dakiniten reflected their associations with the dakinis, a class of demons in Buddhism. Originally the dakinis were associated with jackals instead, but Chinese Buddhist authors presumed that the animal mentioned in this context is basically identicial with more familiar foxes, and that belief reached Japan as well. It was strong enough for Dakinite, the dakini par excellence, to be regularly depicted riding on the back of a fox.

Dakiniten was originally a regular dakini, according to Bernard Faure specifically one who appears in Heian period Enmaten mandalas (Enmaten is related to but not quite the same as the better known king Enma, for the development of two distinct reflections of Yama in Buddhism see here). However, she eventually developed into a full blown deva in her own right, and her prominence was so great that it basically resulted in the decline of references to the generic dakinis in Buddhist literature in Japan. She was particularly popular in the Shingon school of Buddhism, and at the peak of her relevance played a role in royal ascension rituals, developing a connection with Amaterasu in the process (Amaterasu acquired many peculiar connections through the Japanese middle ages, it was par the course). A Tendai treatise equates her with Matarajin instead, though.

An interesting phenomenon related to Dakiniten is the occasional fusion of beliefs pertaining to foxes and tengu, which might have originated in the similarity of the terms tengu and the Japanese term for the already mentioned “heavenly foxes”, tenko. Its best attested examples include the inclusion of tengu in mandalas focused on Dakiniten as her acolytes. However, a different deity ultimately exemplifies this even better.

Iizuna Gongen and "iizuna magic"

Iizuna Gongen riding on the back of a fox (Museum of Fine Arts Boston; link to the source is temporarily dead, the image is reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The indisputable center of the network of connections between foxes and tengu is Iizuna Gongen (飯綱権現), depicted as a tengu riding on a fox. As you can probably guess, he was a (vague) basis for Megumu, as evidenced by the similarity of the names. While many other aspects of his character aren’t really touched upon in the game, I’d hazard a guess he’s also the reason why ZUN decided to include a kuda-gitsune in the same game as Megumu - the evidence lines up exceptionally well, as you’ll see.

Originally Iizuna Gongen was simply the deity of Mount Iizuna (飯綱山), located in the modern Nagano prefecture. Near the end of the Japanese middle ages he spread to other areas, likely thanks to traveling shugenja (also known as yamabushi), mountain ascetics belonging to a religious tradition known as Shugendō. Two aspects of his character are particularly pronounced, his role as a martial deity and his association with foxes.

I was unable to determine when Iizuna Gongen’s connection to foxes originally developed, but it was strong enough to lead to the use of the alternate name Chira Tenko (智羅天狐; “Chira the heavenly fox”) to refer to him. Foxes also appear in a legend describing his origin. It states that he was one of the eighteen children of an Indian king, and arrived in Japan alongside nine of his siblings on the back of a white fox during the reign of emperor Kinmei (the remaining eight went to China and became monks on Mount Tiantai).

His connection to foxes is also reaffirmed in an Edo period treatise, Reflections on Inari Shrine (稲荷神社考, Inari jinja kō), which declares that names such as Iizuna Gongen and Matarajin (sic!) are used in the worship of wild foxes to hide the true nature of the invoked entities. The author further states that the true form of “these matarajin (plural) and wild foxes” is that of a three-faced and six-armed deity, which curiously has more to do with early Matarajin tradition than with Iizuna Gongen as far as I can tell. The two were not really closely associated otherwise, but it’s worth noting that apparently shugenja perceived them both as similar tengu-like deities.

The key feature of conventional iconography of Iizuna Gongen, the fox mount, has nothing to do with Matarajin strictly speaking, and likely reflects the influence of Dakiniten. However, the animal in this context developed its own unique identity thanks to the presence of foxes in a type of ritual focused on Iizuna Gongen, which could itself be referred to as iizuna. The shugenja community centered on the worship of Iizuna Gongen was not very formalized, which led to poor understanding of their practice among outsiders, with the term iizuna basically acquiring the vague meaning along the lines of “magic”. and rather poor reputation. These rites are where the kuda-gitsune comes into play.

Kuda-gitsune in iizuna magic and beyond

The kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

At first glance, kuda-gitsune is just one of many local variants of the standard supernatural fox, similarly to the likes of ninko, osaki-gitsune or nogitsune. The etymology of its name is straightforward. I’m sure you can guess what the second half means, while kuda (管) in this context refers to a bamboo tube. You’d think the name would basically guarantee it was universally accepted that’s how one could carry such a critter undetected, but apparently there was an alternate explanation, namely that it was invisible. I have not seen any further discussion of this in literature, but I assume this might be connected to shikigami beliefs, as these quite often are described as invisible. Do not quote me on that, though. Even more bizarrely, there is no consensus that the animal meant was always a fox. According to Bernard Faure it is distinctly possible the term referred to a weasel.

Kuda-gitsune could be described as a type of shikigami, but note that this term had a much broader meaning in real life than in Touhou, and referred to basically any supernatural being which acted as an extension of the powers attributed to “ritual specialists” (祈祷師) such as onmyōji, shugenja or Buddhist monks. In Buddhist context, the analogous term could be gohō dōji (護法童子; “Dharma-protecting lads”), though there are also cases where gohō and shikigami are contrasted with each other. The shikigami category didn’t just consist of animated papercraft and animal spirits typically designated as such in popculture. Even the twelve heavenly generals defending the “medicine Buddha” Yakushi could be labeled as shikigami. Obviously, kuda-gitsune is closer to the familiar meaning of this term than to Buddhist deities, though.

People relying on kuda-gitsune were referred to as kitsune-tsukai (狐使い), which can be loosely translated as “fox tamer”, and it is said they were often shugenja. Given the popularity of the associated deity among them this shouldn’t really be a surprise.

Various supernatural abilities were ascribed to the kuda-gitsune. The ability to possess people attributed to other supernatural foxes was the domain of kuda-gitsune too. Apparently people afflicted by it were compelled to eat nothing but raw miso. Purportedly they were bringers of wealth - but said wealth did not necessarily come from legitimate sources. That, in turn, could lead to distrust or outright ostracism of people allegedly relying on foxes to acquire wealth. They also provided aid in divination, and could supposedly reveal past, present and future alike this way. However, they could look into the soul of anyone using them this way and learn their secrets. Bernard Faure notes that occasionally it was said that they even could even be utilized to kill enemies who attempted casting spells on their owner.

Shigeru Mizuki's kuda-gitsune

Kuda-gitsune, as depicted by Shigeru Mizuki (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While there isn’t much information about kuda-gitsune in scholarship, especially scholarship available online in English, they received extensive coverage in various books about youkai written by Shigeru Mizuki, famous for arguably canonizing the modern concept of youkai. Note that while I am a fan of Mizuki's works, his encyclopedias are best understood as something closer to Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings, complete with some dubious sourcing and possible fabrications. However, ultimately modern media about youkai, including Touhou, owes much to him, and arguably he continued the tradition of night parade scrolls which often invented new creatures wholesale, so it strikes me as entirely fair game to summarize what he has to say too.

Shigeru Mizuki cited the Edo period writer Matsura Seizan as an authority on kuda-gitsune. He states ccording to the latter, certain ascetics (yamabushi) were provided with these critters upon finishing their training on Mount Kinpu and Mount Ōmine. In his account cited by Mizuki there are a lot of details I haven’t seen elsewhere. The storage tubes after which kuda-gitsune are named apparently had to be inscribed with a certain sanskrit phrase (left unspecified, tragically) so that the animals didn’t have to be fed. However, releasing them and giving it food was necessary to gain their help in divination. There was a downside to this - kuda-gitsune were apparently hard to place back in containment once released without the help of a seasoned specialist. Also, they refused to provide anything of value unless fed well, and they had quite the appetite. Mizuki cites the particularly disastrous case of an ascetic who kept multiple kuda-gitsune in a single tube, and eventually couldn’t pay for enough food for his collection since the animals kept multiplying inside.

According to Mizuki it was believed that a kuda-gitsune could be gifted by its owner to another person, but the creature would come back if it was not satisfied with the food provided by the latter. If the original “fox tamer” dies before passing their kuda-gitsune to someone else, it will instead go to the Ōji Inari shrine located in what is now the the Kita ward of Tokyo.

Conclusion: Tsukasa and her forerunners

In theory I could’ve kept pointing out “see, it’s just like Tsukasa!” in virtually every single paragraph of this article. To answer the question from the title, evidently she is like that because that's how foxes have been in folklore both Japan and China for centuries.

It is not really hard to see that ZUN is genuinely great at research when he wants to be, and Tsukasa's character is remarkably accurate to her real life forerunners, both as an adaptation of kuda-gitsune specifically and as a representation of the broader tradition which lead to the portrayal of foxes as supernatural creatures of questionable moral character. She engages in morally dubious “get rich quick schemes”, she definitely provides advice (of variable quality), and her self-declared ability from her omake bio pretty clearly reflects skills actually ascribed to the kuda-gitsune in folklore. In the newest game the ability to provide information is clearly in the spotlight - Tsukasa seems to be reasonably knowledgeable (she brings up Kojiki in a line aimed at Hisami, among other things), and other characters generally agree she’d be more useful doing something else than fighting. I do not think there’s any real reason to doubt this is what is meant. I think it can even be safely assumed that Zanmu’s decision to pressure Tsukasa to partake in her assassination bluff is rooted in genuine tradition.

I’m obviously not going to say that Tsukasa reaches the platonic ideal of Okina, the quintessential character aimed at fans who like research, who largely seems to exist to get people to dig deeper for sources explaining the dozens of religious allusions in her dialogue, spell cards and design, but I do think it’s worth appreciating that the series reached a stage where even the minor animal youkai can be enjoyed as multilayered representation of centuries worth of genuine folklore and mythology.

Bibliography

-Bernard Faure, Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 1-3

-Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore

-Berthe Jansen and Nobumi Iyanaga, Dākini (Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism)

-Xiaofei Kang, The Cult of the Fox: Power, Gender, and Popular Religion in Late Imperial and Modern China

-Shigeru Mizuki’s assorted writings on kuda-gitsune (collected online here)

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the age of Hindu identity politics (Hindutva) inaugurated in the 1990s by the ascendancy of the Indian People's Party (Bharatiya Janata Party) and its ideological auxiliary, the World Hindu Council (Vishwa Hindu Parishad), Indian cultural and religious nationalism has been promulgating ever more distorted images of India's past.

Few things are as central to this revisionism as Sanskrit, the dominant culture language of precolonial southern Asia outside the Persianate order. Hindutva propagandists have sought to show, for example, that Sanskrit was indigenous to India, and they purport to decipher Indus Valley seals to prove its presence two millennia before it actually came into existence. In a farcical repetition of Romanic myths of primevality, Sanskrit is considered—according to the characteristic hyperbole of the VHP—the source and sole preserver of world culture.

This anxiety has a longer and rather melancholy history in independent India, far antedating the rise of the BJP. [...] Some might argue that as a learned language of intellectual discourse and belles lettres, Sanskrit had never been exactly alive in the first place [...] the assumption that Sanskrit was never alive has discouraged the attempt to grasp its later history; after all, what is born dead has no later history. As a result, there exist no good accounts or theorizations of the end of the cultural order that for two millennia exerted a transregional influence across Asia-South, Southeast, Inner, and even East Asia that was unparalleled until the rise of Americanism and global English. We have no clear understanding of whether, and if so, when, Sanskrit culture ceased to make history; whether, and if so, why, it proved incapable of preserving into the present the creative vitality it displayed in earlier epochs, and what this loss of effectivity might reveal about those factors within the wider world of society and polity that had kept it vital.

[...] What follows here is a first attempt to understand something of the death of Sanskrit literary culture as a historical process. Four cases are especially instructive: The disappearance of Sanskrit literature in Kashmir, a premier center of literary creativity, after the thirteenth century; its diminished power in sixteenth century Vijayanagara, the last great imperial formation of southern India; its short-lived moment of modernity at the Mughal court in mid-seventeenth century Delhi; and its ghostly existence in Bengal on the eve of colonialism. Each case raises a different question: first, about the kind of political institutions and civic ethos required to sustain Sanskrit literary culture; second, whether and to what degree competition with vernacular cultures eventually affected it; third, what factors besides newness of style or even subjectivity would have been necessary for consolidating a Sanskrit modernity, and last, whether the social and spiritual nutrients that once gave life to this literary culture could have mutated into the toxins that killed it. [...]

One causal account, however, for all the currency it enjoys in the contemporary climate, can be dismissed at once: that which traces the decline of Sanskrit culture to the coming of Muslim power. The evidence adduced here shows this to be historically untenable. It was not "alien rule un sympathetic to kavya" and a "desperate struggle with barbarous invaders" that sapped the strength of Sanskrit literature. In fact, it was often the barbarous invader who sought to revive Sanskrit. [...]

One of these was the internal debilitation of the political institutions that had previously underwritten Sanskrit, pre-eminently the court. Another was heightened competition among a new range of languages seeking literary-cultural dignity. These factors did not work everywhere with the same force. A precipitous decline in Sanskrit creativity occurred in Kashmir, where vernacular literary production in Kashmiri-the popularity of mystical poets like Lalladevi (fl. 1400) notwithstanding-never produced the intense competition with the literary vernacular that Sanskrit encountered elsewhere (in Kannada country, for instance, and later, in the Hindi heartland). Instead, what had eroded dramatically was what I called the civic ethos embodied in the court. This ethos, while periodically assaulted in earlier periods (with concomitant interruptions in literary production), had more or less fully succumbed by the thirteenth century, long before the consolidation of Turkish power in the Valley. In Vijayanagara, by contrast, while the courtly structure of Sanskrit literary culture remained fully intact, its content became increasingly subservient to imperial projects, and so predictable and hollow. Those at court who had anything literarily important to say said it in Telugu or (outside the court) in Kannada or Tamil; those who did not, continued to write in Sanskrit, and remain unread. In the north, too, where political change had been most pronounced, competence in Sanskrit remained undiminished during the late-medieval/early modern period. There, scholarly families reproduced themselves without discontinuity-until, that is, writers made the decision to abandon Sanskrit in favor of the increasingly attractive vernacular. Among the latter were writers such as Kesavdas, who, unlike his father and brother, self-consciously chose to become a vernacular poet. And it is Kesavdas, Biharilal, and others like them whom we recall from this place and time, and not a single Sanskrit writer. [...]

The project and significance of the self-described "new intellectuals" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries [...] what these scholars produced was a newness of style without a newness of substance. The former is not meaningless and needs careful assessment and appreciation. But, remarkably, the new and widespread sense of discontinuity never stimulated its own self-analysis. No idiom was developed in which to articulate a new relationship to the past, let alone a critique; no new forms of knowledge-no new theory of religious identity, for example, let alone of the political-were produced in which the changed conditions of political and religious life could be conceptualized. And with very few exceptions (which suggest what was in fact possible), there was no sustained creation of new literature-no Sanskrit novels, personal poetry, essays-giving voice to the new subjectivity. Instead, what the data from early nineteenth-century Bengal-which are paralleled every where-demonstrate is that the mental and social spheres of Sanskrit literary production grew ever more constricted, and the personal and this-worldly, and eventually even the presentist-political, evaporated, until only the dry sediment of religious hymnology remained. [...]

In terms of both the subjects considered acceptable and the audience it was prepared to address, Sanskrit had chosen to make itself irrelevant to the new world. This was true even in the extra-literary domain. The struggles against Christian missionizing, for example, that preoccupied pamphleteers in early nineteenth-century Calcutta, took place almost exclusively in Bengali. Sanskrit intellectuals seemed able to respond, or were interested in responding, only to a challenge made on their own terrain-that is, in Sanskrit. The case of the professor of Sanskrit at the recently-founded Calcutta Sanskrit College (1825), Ishwarachandra Vidyasagar, is emblematic: When he had something satirical, con temporary, critical to say, as in his anti-colonial pamphlets, he said it, not in Sanskrit, but in Bengali. [...]

No doubt, additional factors conditioned this profound transformation, something more difficult to characterize having to do with the peculiar status of Sanskrit intellectuals in a world growing increasingly unfamiliar to them. As I have argued elsewhere, they may have been led to reaffirm the old cosmopolitanism, by way of ever more sophisticated refinements in ever smaller domains of knowledge, in a much-changed cultural order where no other option made sense: neither that of the vernacular intellectual, which was a possible choice (as Kabir and others had earlier shown), nor that of the national intellectual, which as of yet was not. At all events, the fact remains that well before the consolidation of colonialism, before even the establishment of the Islamicate political order, the mastery of tradition had become an end in itself for Sanskrit literary culture, and reproduction, rather than revitalization, the overriding concern. As the realm of the literary narrowed to the smallest compass of life-concerns, so Sanskrit literature seemed to seek the smallest possible audience. However complex the social processes at work may have been, the field of Sanskrit literary production increasingly seemed to belong to those who had an "interest in disinterestedness," as Bourdieu might put it; the moves they made seem the familiar moves in the game of elite distinction that inverts the normal principles of cultural economies and social orders: the game where to lose is to win. In the field of power of the time, the production of Sanskrit literature had become a paradoxical form of life where prestige and exclusivity were both vital and terminal.

The Death of Sanskrit, Sheldon Pollock, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Apr., 2001), pp. 392-426 (35 pages)

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding 18th Century

There's a prevailing problem I've noticed in interpreting frev: people not really understanding that this was 18th century. Oh, they understand it on an intellectual level, but they still apply today's worldview to it. And you can't do that if you wish to understand wtf was going on.

(This is not about anyone here nor a shade at anyone in particular. Just a trend I've noticed, especially in bad takes).

All historical periods have this problem where people interpret things from the point of view of our own time. So that's hardly special about frev and 18c. But a tricky part is that 18c saw the development of things that we still use today (constitutions, voting system, etc.) that it may seem like it's more similar to our world than it actually was.

For example. The voting system. They had it and so do we. Except they were assholes who didn't allow women to vote. (Which is fair criticism, but people often forget that not all men had the right to vote either - so any criticism of exclusion should take that into account. Was it really about women per se, or about their ideas on who can and cannot make a free and rational vote? What is that they saw wrong about women and certain men voting? - Their attitude sure sucks, but if we ask these questions we understand better what was going on vs just going "sexist men", which only explains part of the issue). Or: journalism. They had political slander and so do we. But uuugh, their slander was so openly personal and often ridiculed someone's looks/sexual practices in supposedly serious political attacks - wtf was that? Or: trials. Of course we all know how trials are supposed to be done and what kind of arguments/evidence they should include. The fact they focused so much on character slander is incorrect and ridiculous, and...

Stop. Instead of assuming that they "did it incorrectly", think about: 1) how we do these things today is a product of decades/centuries of development; they didn't have that. They were only inventing it for the first time. 2) They did stuff according to their cultural beliefs. If they focused so much on character assassination as an argument, it means it was significant for their worldview.

You might not like it (and fair enough) but it's not possible to understand what was going on unless we understand how they thought and what they knew and what their worldview was. Which is not easy. It's not simply about knowing the state of scientific thought or what they believed about the world. Understanding how this affected the way they thought and how they interpreted things, or how they build meaning and conclusions - none of that is easy. But we have to question our assumptions, even if we're unable to see things from their pov. Because that's the only way not to arrive at wrong conclusions.

Similarly, many terms what they used had a different meaning to how they are used today (or, at least, they were understood in ways dissimilar to how we use them). Concepts such as despotism, tyranny, dictator, terror; also some seemingly easy to understand terms like "being a moderate" or even "patriotism". If we assume 18th century people used them in the same way that we do, we won't be able to understand wtf they are talking about.

#this is not about 18c or frev specifically#but it's a good example#many bad takes about frev include this lack of understanding#coupled with interpreting past with present#and it's bad#and hey it's not just about frev#royalism too#like i am not a fan of louis or marie antoinette but their actions too have to be interpreted from 18th century worldview#like of course they did stuff that they did#they fought for what they believed in their souls was the truth#natural hierarchies aming humans and the monarch's right to rule etc.#and many of people - not just rich and powerful- also believed that#i don't think any of that is good but it was a worldview they operated under#so to understand their actions we need to know that#or anyone's action#not to excuse it but to understand wtf was going on#because applying our understanding cannot explain it#frev#french revolution

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.2.3 Are anarchists in favour of organisation?

Yes. Without association, a truly human life is impossible. Liberty cannot exist without society and organisation. As George Barrett pointed out:

“To get the full meaning out of life we must co-operate, and to co-operate we must make agreements with our fellow-men. But to suppose that such agreements mean a limitation of freedom is surely an absurdity; on the contrary, they are the exercise of our freedom.

“If we are going to invent a dogma that to make agreements is to damage freedom, then at once freedom becomes tyrannical, for it forbids men to take the most ordinary everyday pleasures. For example, I cannot go for a walk with my friend because it is against the principle of Liberty that I should agree to be at a certain place at a certain time to meet him. I cannot in the least extend my own power beyond myself, because to do so I must co-operate with someone else, and co-operation implies an agreement, and that is against Liberty. It will be seen at once that this argument is absurd. I do not limit my liberty, but simply exercise it, when I agree with my friend to go for a walk.

“If, on the other hand, I decide from my superior knowledge that it is good for my friend to take exercise, and therefore I attempt to compel him to go for a walk, then I begin to limit freedom. This is the difference between free agreement and government.” [Objections to Anarchism, pp. 348–9]

As far as organisation goes, anarchists think that “far from creating authority, [it] is the only cure for it and the only means whereby each of us will get used to taking an active and conscious part in collective work, and cease being passive instruments in the hands of leaders.” [Errico Malatesta, Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 86] Thus anarchists are well aware of the need to organise in a structured and open manner. As Carole Ehrlich points out, while anarchists “aren’t opposed to structure” and simply “want to abolish hierarchical structure” they are “almost always stereotyped as wanting no structure at all.” This is not the case, for “organisations that would build in accountability, diffusion of power among the maximum number of persons, task rotation, skill-sharing, and the spread of information and resources” are based on “good social anarchist principles of organisation!” [“Socialism, Anarchism and Feminism”, Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 47 and p. 46]

The fact that anarchists are in favour of organisation may seem strange at first, but it is understandable. “For those with experience only of authoritarian organisation,” argue two British anarchists, “it appears that organisation can only be totalitarian or democratic, and that those who disbelieve in government must by that token disbelieve in organisation at all. That is not so.” [Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer, The Floodgates of Anarchy, p. 122] In other words, because we live in a society in which virtually all forms of organisation are authoritarian, this makes them appear to be the only kind possible. What is usually not recognised is that this mode of organisation is historically conditioned, arising within a specific kind of society — one whose motive principles are domination and exploitation. According to archaeologists and anthropologists, this kind of society has only existed for about 5,000 years, having appeared with the first primitive states based on conquest and slavery, in which the labour of slaves created a surplus which supported a ruling class.

Prior to that time, for hundreds of thousands of years, human and proto-human societies were what Murray Bookchin calls “organic,” that is, based on co-operative forms of economic activity involving mutual aid, free access to productive resources, and a sharing of the products of communal labour according to need. Although such societies probably had status rankings based on age, there were no hierarchies in the sense of institutionalised dominance-subordination relations enforced by coercive sanctions and resulting in class-stratification involving the economic exploitation of one class by another (see Murray Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom).

It must be emphasised, however, that anarchists do not advocate going “back to the Stone Age.” We merely note that since the hierarchical-authoritarian mode of organisation is a relatively recent development in the course of human social evolution, there is no reason to suppose that it is somehow “fated” to be permanent. We do not think that human beings are genetically “programmed” for authoritarian, competitive, and aggressive behaviour, as there is no credible evidence to support this claim. On the contrary, such behaviour is socially conditioned, or learned, and as such, can be unlearned (see Ashley Montagu, The Nature of Human Aggression). We are not fatalists or genetic determinists, but believe in free will, which means that people can change the way they do things, including the way they organise society.

And there is no doubt that society needs to be better organised, because presently most of its wealth — which is produced by the majority — and power gets distributed to a small, elite minority at the top of the social pyramid, causing deprivation and suffering for the rest, particularly for those at the bottom. Yet because this elite controls the means of coercion through its control of the state (see section B.2.3), it is able to suppress the majority and ignore its suffering — a phenomenon that occurs on a smaller scale within all hierarchies. Little wonder, then, that people within authoritarian and centralised structures come to hate them as a denial of their freedom. As Alexander Berkman puts it:

“Any one who tells you that Anarchists don’t believe in organisation is talking nonsense. Organisation is everything, and everything is organisation. The whole of life is organisation, conscious or unconscious … But there is organisation and organisation. Capitalist society is so badly organised that its various members suffer: just as when you have a pain in some part of you, your whole body aches and you are ill… , not a single member of the organisation or union may with impunity be discriminated against, suppressed or ignored. To do so would be the same as to ignore an aching tooth: you would be sick all over.” [Op. Cit., p. 198]

Yet this is precisely what happens in capitalist society, with the result that it is, indeed, “sick all over.”

For these reasons, anarchists reject authoritarian forms of organisation and instead support associations based on free agreement. Free agreement is important because, in Berkman’s words, ”[o]nly when each is a free and independent unit, co-operating with others from his own choice because of mutual interests, can the world work successfully and become powerful.” [Op. Cit., p. 199] As we discuss in section A.2.14, anarchists stress that free agreement has to be complemented by direct democracy (or, as it is usually called by anarchists, self-management) within the association itself otherwise “freedom” become little more than picking masters.

Anarchist organisation is based on a massive decentralisation of power back into the hands of the people, i.e. those who are directly affected by the decisions being made. To quote Proudhon:

“Unless democracy is a fraud and the sovereignty of the People a joke, it must be admitted that each citizen in the sphere of his [or her] industry, each municipal, district or provincial council within its own territory … should act directly and by itself in administering the interests which it includes, and should exercise full sovereignty in relation to them.” [The General Idea of the Revolution, p. 276]

It also implies a need for federalism to co-ordinate joint interests. For anarchism, federalism is the natural complement to self-management. With the abolition of the State, society “can, and must, organise itself in a different fashion, but not from top to bottom … The future social organisation must be made solely from the bottom upwards, by the free association or federation of workers, firstly in their unions, then in the communes, regions, nations and finally in a great federation, international and universal. Then alone will be realised the true and life-giving order of freedom and the common good, that order which, far from denying, on the contrary affirms and brings into harmony the interests of individuals and of society.” [Bakunin, Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, pp. 205–6] Because a “truly popular organisation begins … from below” and so “federalism becomes a political institution of Socialism, the free and spontaneous organisation of popular life.” Thus libertarian socialism “is federalistic in character.” [Bakunin, The Political Philosophy of Bakunin, pp. 273–4 and p. 272]

Therefore, anarchist organisation is based on direct democracy (or self-management) and federalism (or confederation). These are the expression and environment of liberty. Direct (or participatory) democracy is essential because liberty and equality imply the need for forums within which people can discuss and debate as equals and which allow for the free exercise of what Murray Bookchin calls “the creative role of dissent.” Federalism is necessary to ensure that common interests are discussed and joint activity organised in a way which reflects the wishes of all those affected by them. To ensure that decisions flow from the bottom up rather than being imposed from the top down by a few rulers.

Anarchist ideas on libertarian organisation and the need for direct democracy and confederation will be discussed further in sections A.2.9 and A.2.11.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eye of newt and toe of frog: what was really in the witches’ cauldron in Macbeth?

(CW: torture, death, historical racism, historical antisemitism, animal and human body parts)

Ever since Scott Cunningham first made the following claim in the 1980s, there has been an increasingly widely circulated belief that the ingredients of the Macbeth potion were not grisly animal parts at all but merely herbs and plants, concealed under code names:

“every ingredient (Shakespeare) lists as being in the witches' pot refers to a plant and not the gruesome substance popularly thought”

This proposal had not appeared at all in analyses of Shakespeare prior to Cunningham’s Magical Herbalism: The Secret Craft of the Wise but is now extremely popular, especially the often-cited proposal that ‘eye of newt really meant mustard seed’. Lists of ‘herbal codes’ circulate online, purporting to explain all the different ingredients of the Macbeth potion away as plants. Witches, according to these lists, were grossly misrepresented. Their grisly concoctions were nothing but herbal mixtures.

Code-names and substitutions have certainly played a part in magic in history. Cunningham was familiar with, and makes reference to, the Greek Magical Papyri in which a famous list of secret substitutions is given. For example, ‘the tears of a Hamadryas baboon’ are to be taken to mean ‘dill juice’. The concept of a secret herbal code in which grisly-seeming or mythical ingredients are in fact plants – and only the enlightened few are aware of this - was therefore not a new one.

Was Cunningham correct?

First let’s look at the historical context.

Shakespeare wrote Macbeth under the patronage of James VI of Scotland / I of England. The King was paranoid about witches, was personally present at the interrogation of at least one, and wrote a book called Daemonologie all about them. The depiction of witches in Macbeth would have needed to flatter and support the King’s personal convictions. These fictional witches are therefore evil through and through, and we should be suspicious of any interpretation that seeks to lessen their horror.

Other plays were written around the same time that feature witches in similar roles, such as Jonson’s Masque of Queens and Middleton’s The Witch. We will come to those in due time.

Let’s examine the evidence for Cunningham’s claim, line by line.

Round about the cauldron go;

In the poison’d entrails throw.

Right from the start, we have a reference to ‘poison’d entrails’. This immediately tells us that the ingredients are characterised both by being poisonous or venomous in nature and by coming from living creatures. Herbs and plants do not have entrails.

Toad, that under cold stone

Days and nights hast thirty one

Swelter’d venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i’ the charmed pot.

The first ingredient is, quite plainly, a living toad. Specifically, it is a toad that has been secreting venom over a period of time.

The choice of a venom-secreting toad as the very first ingredient cannot have been a coincidence, seeing as the King had himself interrogated an accused witch who had been put to torture, and who had ‘confessed’ to collecting toad’s venom in order to use it in a sorcerous attempt against the King’s life.

The alleged witch’s name was Agnis Thompson, and the King interrogated her in 1591. His account of this is written up in his book, Daemonologie. Agnis Thompson 'confessed' to having taken a black toad, hung it up and collected the venom that dripped from it over three days in an oyster shell. This venom was supposedly intended to be used in a spell that would bewitch the King to death, 'and put him to such extraordinary paines, as if he had beene lying vpon sharp thornes and endes of Needles.'

It is worth noting at this point that the King also recorded his belief that the Devil causes witches to "joint dead corpses, & to make powders thereof" which are then used in spells. This belief can also be found in Daemonologie.

So in the very first ingredient that goes into the cauldron, the live toad steeped in its own venom, we have an immediate disproof of Cunningham’s claim that ‘every ingredient refers to a plant’, along with a clear reference to the King’s own personal lived experience and profound beliefs concerning witches.

It ought to go without saying that King James VI/I was a deluded bigot who had innocent women tortured and put to death in service to his twisted agenda, but let’s say it anyway.

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the cauldron boil and bake;

As with ‘entrails’, the use of the term ‘fillet’ leaves in no doubt that we are dealing with a dismembered living creature. A fenny snake is simply a snake from the fens.

Convoluted attempts have been made to identify ‘fillet of a fenny snake’ as a plant of some kind, but given that Cunningham’s claim has already been disproved, there seems no point in not taking Shakespeare at face value.

Eye of newt

Let’s get this out of the way: there is zero historical evidence that ‘eye of newt’ ever meant ‘mustard seed’. There are no herbals that give this as a name – not that were written prior to the 1980s, at any rate. The obvious conclusion is that it is modern lore created in sympathy with Cunningham’s claim. The ‘mustard seed’ interpretation is all over the Internet, of course, because sites typically copy one another without bothering to look for original sources.

(I would like to say, for the record, that if I assert here that ‘no historical source says X was ever used to mean Y’ and anyone later provides a historical source that unambiguously DOES say X was used to mean Y, I will print this article out and eat it. With mustard.)

Assertions that eye of newt meant mustard seed usually also assert that it was a popular component of witches’ spells. In fact, Macbeth is the one and only historical instance of ‘eye of newt’ appearing as a spell component. It is famous because the play is famous, not because it was in widespread use. The idea that it was a codename for some other ingredient thus appears even less credible.

Other attempts to interpret Shakespeare according to the Cunningham agenda include the rival claim, sometimes seen, that ‘eye of newt’ actually meant a type of daisy. Just as with mustard seed, there is no historical evidence at all to support this.

We should perhaps expect to encounter multiple claims as to the ‘real meaning’ of the potion ingredients, because the point of these claims is not to provide a definitive substitution code that was actually used by practitioners of the past, but simply to repeat the insistence that Shakespeare’s words do not mean what they say.

It is, of course, possible to assert that the enlightened ‘mustard seed’ interpretation has simply been handed down secretly through the years from witch to witch, never once appearing in print until the 1980s when such things could at last be shared openly within the hallowed pages of Llewellyn books. Claims of this sort are unanswerable.

Incidentally, the typical construction for plant names is not ‘B of A’, but ‘A’s B’ or simply ‘AB’, as we find with names like day’s eye (daisy), baby’s breath, coltsfoot and foxglove. If Shakespeare’s spell had run ‘breath of babe and eye of ox / foot of colt and glove of fox’ then we would be having a very different conversation.

Tongue of dog

This ingredient is the first one where the Cunningham agenda might seem credible, if it had not already been disproven by the very first of the ingredients. There is a herb called ‘houndstongue’, Cynoglossum officinale, which is also known as houndstooth and dog’s tongue.

Was Shakespeare referring to a herb here, then, rather than the tongue of a literal dog? Given the anatomical specificity of some of the later ingredients, there is no reason to think so. Animal tongues have played a part in magic for centuries. The Epistula Vulteris (800 CE), for example, proposes putting a vulture’s tongue in your shoe to make enemies adore you. The 16th century Tree of Knowledge instructs the reader to take the tongue of a hoopoe and hang it on the right side of the body, close to the heart, in order to defeat anyone in court.

Wool of bat

Despite this ingredient being relatively innocuous – ‘wool’ could theoretically be harvested from a bat without harming it – attempts have been made to identify this as moss, or even as holly leaves, via a convoluted train of association that links the shape of bat’s wings with the shape of holly.

No historical sources give ‘wool of bat’ or ‘bat’s wool’ as a term for a plant.

Toe of frog

Some modern sources assert that ‘toe of frog’ refers to the buttercup, possibly because the Latin name Ranunculus means ‘little frog’. One is left to wonder what part of a buttercup the ‘toe’ might refer to.

Unfortunately, no historical sources give ‘toe of frog’ or ‘frog’s toe’ as a term for a plant.

Adder’s fork

At first sight this looks like another possible point for Cunningham. Adders have forked tongues, and there are several plants that bear the name ‘adder’s tongue’. However, there is no evidence of the use of the specific term ‘adder’s fork’ to refer to a plant.

We would also have to explain why, given that these ingredients are demonstrably not being presented in an overall context of plant symbolism, any of the plants known as adder’s tongue would be intended here over the surface meaning.

Blindworm’s sting

The ‘sting’ (fang) of a venomous snake, or possibly a slow-worm, which are ironically not venomous. This ingredient is probably intended to pair with the last one: they are both from the mouths of reptiles.

No historical sources give ‘blindworm’s sting’ as a term for a plant.

Lizard’s leg

The leg of a lizard.

No historical sources give ‘lizard’s leg’ as a term for a plant.

Owlet’s wing

The wing of an owlet, or baby owl.

No historical sources give ‘owlet’s wing’ as a term for a plant. (I am getting as tired of typing this as you probably are of reading it.)

Scale of dragon

An ingredient that at first glance appears to buttress Cunningham’s claim, because unlike the others it cannot possibly mean what it says. Dragons don’t exist. However, ingredients that use the term ‘dragon’ in their naming do exist, such as ‘dragon’s blood’.

Excitingly, there is a plant known as the dragon’s scale fern, Pyrrosia piloselloides. Should we concede a point to Cunningham here?

Unfortunately, I do not think we can. The dragon’s scale fern is native to Singapore and was first catalogued by Carl Linnaeus in 1763. There seems no way that Shakespeare could possibly have heard of it. Moreover, ‘dragon’s scale’ is merely an English translation of the term ‘sisek naga’. I’ve been unable to find any use of the name ‘dragon’s scale fern’ in English prior to the 20th century.

Did Shakespeare mean a literal dragon, then? Considering his plays involve literal ghosts (e.g. Caesar, Banquo, Hamlet’s father), literal monsters (Caliban) and literal witches with the power to ‘hover through the fog’ and summon storms at sea, we needn’t worry about Shakespeare depicting things which we now know to be impossible. So yes, literal dragon’s scale.

Tooth of wolf

It is tempting to identify this ingredient as the herb houndstooth, but the problem there is that houndstooth is the same as houndstongue, for which see ‘tongue of dog’ above.

No historical sources give ‘wolf’s tooth’ as a term for a plant.

Witches’ mummy

Either ‘the mummified flesh of dead witches’ or ‘mummified human flesh, as used by witches’.

Bizarre though it may sound, mummified human flesh was used for medical purposes before and after Shakespeare’s time. See Sir Thomas Browne, Hydriotaphia, 1658: ‘The Egyptian mummies which Cambyses spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummy is become merchandize, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams.’

No historical sources give ‘witches’ mummy’ as a term for a plant.

Maw and gulf

Of the ravin’d salt-sea shark

The mouth and stomach of a shark.

No historical sources give ‘shark’s maw’, ‘shark’s gulf’ or ‘shark’s stomach’ as a term for a plant. There is a succulent called Shark's Mouth Mesemb that is native to South Africa, but given the additional description lavished on the shark – ‘ravin’d, salt-sea’ – it seems pretty obviously a literal shark.

Root of hemlock digg’d i’ the dark

Here we come to our first actual plant ingredient, which is named as such. Do please note the significance of ‘digg’d i’ the dark’. It’s not just hemlock, it’s hemlock that has been gathered in the ‘proper’ way. Where literal plants are concerned, the time and method of harvesting is magically significant. This suggests that far from everything in the spell being a plant as Cunningham proposed, the actual plants involved are special and treated with particular care.

Liver of blaspheming Jew

Exactly what it appears to be, disgusting historical antisemitism and all.

Gall of goat

The gall (bile) of a goat. (Goat’s gall and honey were used as a treatment for cancer in Saxon times. Who knew?)

No historical sources give ‘goat’s gall’ or ‘goat’s bile’ as a term for a plant.

Slips of yew

Sliver’d in the moon’s eclipse

Another actual plant ingredient, named as such. Just as we saw with the hemlock root, when the spell calls for actual plants, the witch is careful to specify the method of gathering. ‘Sliver’d in the moon’s eclipse’ means that the yew was peeled off in slivers during an eclipse of the moon.

Nose of Turk

The literal nose of a literal Turkish person. My suspicion is that this mocking of foreign people and their religions was deliberate pandering to the King, almost to the point of pantomime.

Tartar’s lips

See above.

Finger of birth-strangled babe

Ditch-deliver’d by a drab

The severed finger of a baby strangled at birth, having been born in a ditch to a sex worker.

There is a Korean succulent called ‘baby’s finger’ but there is no hope whatsoever that Shakespeare could have meant something so innocent.

Tiger’s chaudron

A tiger’s entrails. Derives from the exact same source as ‘cauldron’, so Shakespeare was frankly cheating a bit to use it as a rhyme here.

No historical sources give ‘tiger’s chaudron’ or ‘tiger’s entrails’ as a term for a plant.

A baboon’s blood

Curiously, ‘the blood of a Hamadryas baboon’ is one of the ingredients in the Greek Magical Papyri which is deemed to be a code name. Unfortunately for Cunningham, the ingredient it is a code name for is the blood of a spotted gecko, bringing us all the way back to lizard’s legs and newts’ eyes.

It’s worth noting in passing that Shakespeare wouldn’t have been familiar with the Papyri Graecae Magicae, given that they weren’t rediscovered and republished until the 19th century.

In any case, no historical sources give ‘baboon’s blood’ as a term for a plant.

In summary, of the twenty-three ingredients that go into the witches’ cauldron:

two – yew and hemlock - are unambiguously plants and named as such, with the method of gathering described

two – tongue of dog and adder’s fork – resemble extant folk names for plants, i.e. houndstongue and adder’s tongue

the remaining nineteen are all animal or human body parts, or in the case of the toad, the entire animal

Cunningham does not seem to have considered that disguising innocent herbs with grisly sounding names would have invited trouble rather than deflecting it. For example, even if ‘wool of bat’ had been a codename for moss, no practitioner with an ounce of sense would have referred to it as such when they could just call it moss. Gathering moss might be eccentric; gathering wool of bat could be seen as diabolic.

Some commentators have taken the view that Shakespeare might have been using ironic humour, by listing ingredients that were grisly sounding but also folk names for ordinary plants, intending the audience to pick up on his clever references. The audience would, so the theory claims, have recognised the wordplay because the folk names would have been in common use at the time. This theory falls apart, however, simply because the vast majority of the ingredients were not folk names for plants, and only two can possibly be considered such. Even in their case it is necessary to use some creative interpretation.

There is an additional problem with the ‘secret herbal code’ hypothesis. Cunningham’s core argument is that ‘witches, magicians and occultists wished to keep secret the most powerful of the old magics’, hence the use of codes. And yet, the arguments advanced for which ingredient represents which plant are based on common folk names, not secret lore unavailable to the masses. One cannot draw a link between ‘tongue of dog’ and the herb houndstongue, insist that the parallel is obvious, and then claim that this was a secret code.

To use the Papyri Graecae Magicae as an example of a genuine secret substitution system, ‘a physician’s bone’ is code for ‘sandstone’. There is no conceivable way a person could have inferred the real ingredient from its code name. And yet, the supposed herbal codenames in Macbeth are all based on inference, such as ‘finger of birth-strangled babe’ being taken to mean ‘bloody finger’ and thus ‘foxglove’.

Media magica in other Jacobean dramas

As mentioned above, it was not only Shakespeare who wrote plays in which witches prepared concoctions that contained human or animal body parts. However, only Shakespeare seems to have been singled out for his alleged use of secret herbal code names (which, as we have seen, does not bear scrutiny).

Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Queens was written for King James VI/I and was first performed in February 1609 (three years after Macbeth) in honour of the King’s eldest son, Prince Henry. Like Macbeth, it flatters the King’s obsession with witches by featuring a gathering of them. They discuss the ingredients they have gathered, such as:

I have been all day, looking after

A raven, feeding upon a quarter;

And, soon, as she turn'd her beak to the south,

I snatch'd this morsel out of her mouth.

This hag has snatched a morsel of human corpse that had been cut into four pieces (as in ‘hung, drawn and quartered’) out of the beak of a raven.

Just as in ‘Macbeth’, we then hear of a miscellany of gruesome ingredients, such as the bitten-off sinews of a hanged murderer, the fat of an infant, the brains of a cat, frog’s blood and backbone, owl’s eyes, viper’s skin and basilisk’s blood, none of which can possibly be taken to be codenames for plants. Moreover, we are fortunate to have Jonson’s own notes on his work, in which he laboriously details the sources he used and the practices he intends to depict:

But we apply this examination of ours to the particular use; whereby, also, we take occasion, not only to express the things (as vapours, liquors, herbs, bones, flesh, blood, fat, and such like,

which are called Media magica) but the rites of gathering them, and from what places, reconciling as near as we can, the practice of antiquity to the Neoterick and making it familiar with our popular witchcraft.

Jonson’s representation of plants is of particular interest here. He has one hag declare:

And I have been plucking, plants among,

Hemlock, henbane, adder's-tongue,

Night-shade, moon-wort, libbard's-bane;

And twice, by the dogs, was like to be ta'en.

And offers the following explanatory text:

Cicuta, hyoscyarnus, ophioglosson, solanum, martagon, doronicum, aconitum are the common venefical ingredients remembered by Paracelsus, Porta, Agrippa, and others; which I make her

to have gathered, as about a castle, church, or some vast building (kept by dogs) among ruins and wild heaps.

Just as with Shakespeare’s mention of hemlock and yew, there is no suggestion of code names.

‘The Witch’ by Thomas Middleton was also performed by the King’s Men. It, too, depicts witches in exactly the way the King expected to see them depicted. For example, Hecate says to Stadlin:

[Giving her a dead child's body] Here, take this unbaptised brat.

Boil it well, preserve the fat

The subject of herbs comes up in this graphic exchange:

STADLIN

Where be the magic herbs?

HECATE

They're down his throat:

His mouth cramm'd full, his ears and nostrils stuff'd.

I thrust in eleoselinum lately

Aconitum, frondes populeas, and soot-

You may see that, he looks so b[l]ack i' th' mouth-

Then sium, acorum vulgare too,

[Pentaphyllon], the blood of a flitter-mouse,

Solanum somnificum et oleum.

Middleton even brings a comic touch to the loathsomeness of the witches’ concoctions. Almachildes (who has brought the witches toads in marzipan as a gift) is invited to dine with them, and responds

How? Sup with thee? Dost think I'll eat fried rats

And pickled spiders?

Conclusions

The witches depicted by Shakespeare, Jonson and Middleton for the entertainment of King James VI/I are shown employing animal and human body parts as well as plants in their spells, in accordance with the King’s personal beliefs and with the playwrights’ understanding of magic as depicted in such texts as Cornelius Agrippa’sDe Occulta Philosophia.

There is no evidence to support the suggestion that any of the ingredients named are meant to be taken other than literally. They are not codenames for plants. Eye of newt in particular is not a folk name for mustard seed and never has been.

Scott Cunningham’s assertion that “every ingredient (Shakespeare) lists as being in the witches' pot refers to a plant and not the gruesome substance popularly thought” is simply wrong.

Although Cunningham was wrong, and may well have known it, his motivation is understandable. Modern witches are revolted by the idea of body parts being used in spells and wish to distance themselves from it. The ‘herbal code’ interpretation provided a means to recast the horrific Jacobean witch (who did not exist outside of the popular and kingly imagination) as an enlightened and humane herbalist.

But if we allow ourselves to misrepresent Shakespeare in this way, we risk erasing the memory of the real victims: Agnis Thompson, the accused witch who was tortured into ‘confessing’ her use of a toad, and her fellows. Squeamishness must not be allowed to prevent us from confronting the uncomfortable facts of history.

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

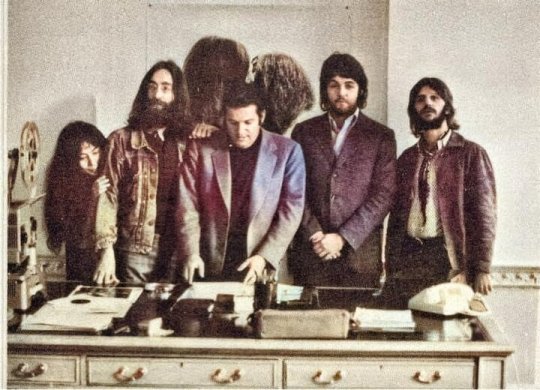

The day the world found out about the breakup of the Beatles

This sad day was April 10, 1970, when the auto interview was published Paul McCartney, timed to coincide with the imminent release of his McCartney solo album. The release did not directly mention the breakup, but it became obvious to fans.

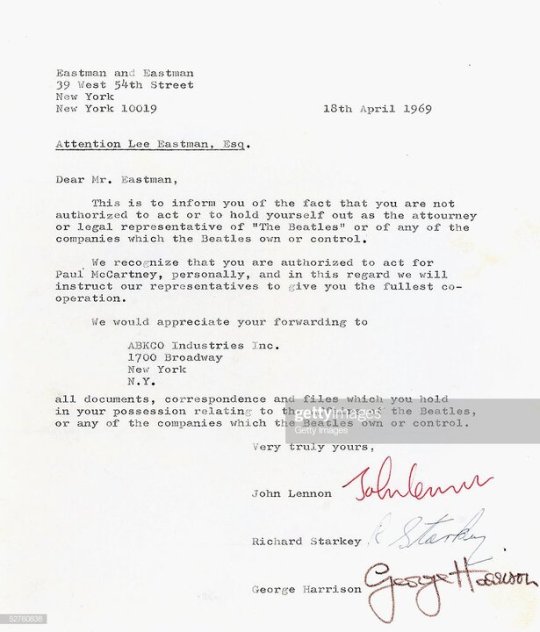

This document is signed John Lennon, Richard Starkey (aka Ringo) and George Harrison, were sold at auction for 325 thousand dollars.

April 18, 1969

Dear Mr. Eastman,

We hereby inform you that you are not authorized to act or present yourself as a trustee or legal representative of The Beatles or any of the companies that The Beatles own or control.

We recognize that you are authorized to act on behalf of Paul McCartney personally, and in this regard, we will instruct our representatives to provide you with the fullest cooperation.

We will be grateful to you for forwarding to the address:

ABKCO Industries Inc.

1700 Broadway

New York

NY

of all documents, correspondence and files in your possession relating to the affairs of the Beatles or any of the companies that the Beatles own or control.

With respect,

John Lennon

Richard Starkey

George Harrison

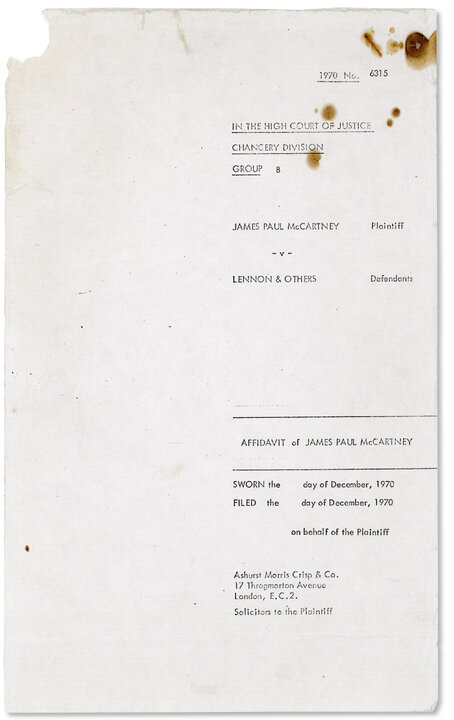

The beginning of the end: a lawsuit Paul McCartney in 1970, initiating the trial of the dissolution of the Beatles, with handwritten comments John Lennon, refuting the accusations McCartney. A historic and noteworthy document that marks the official action to end the partnership that has dominated pop music since 1964. On New Year's Eve 1970 McCartney took a fateful step after years of infighting and creative differences, many of which are outlined in the 25-point list of the lawsuit.

One of the key reasons given is Paul, is the band's decision to stop touring:

“While we were touring, the relationship between us was very close.”

As for their studio showdown, McCartney claims that:

“Lennon was no longer interested in performing those songs that he had not composed himself.”

Paul and Linda outside the courthouse, 1971

He also claimed that being a member of the Beatles posed a threat to his creative freedom. Finally, he stated that no reports had ever been provided to the partnership since its inception.

Lennon objects to this:

“There are a lot of quarrels about leadership on the tour”

As long as The Beatles became more and more a studio band, and they began to creatively distance themselves from each other.

“The musical differences became more pronounced,”

and by the time the band recorded Abbey Road, Lennon was no longer interested

“in performing songs that he had not composed himself.” Lennon responds: “

Paul has been responsible for this for many years.”

youtube

When, according to McCartney, Lennon finally expressed a wish “get divorced,” he explained, as he claims Paul said that “in fact” the band had come full circle because the photo of the band that would be used on Get Back [became the Let It Be album. - Approx.perev.], so similar to their first album.

“It never happened,” Lennon exclaimed.

One of the last drops for Paul was the question of the release date of his McCartney solo album. Apple tried to delay the release, and McCartney saw this action as a threat to his creative freedom. To this accusation Lennon replied that the band was “outraged by how unceremoniously his record ‘suddenly’ appeared, and demanded a release date without taking into account other Apple releases.”

Paul also disliked Phil Spector's work on Let it Be, and claimed that he was not consulted - which “never happened before.” Lennon countered that it “happened in the early days.”

No group meetings were held between April and August. In April McCartney wrote To Lennon, “suggesting that we ‘let each other out of the trap’.”

According to Gender, John responded by attaching a photo of himself and Yoko Ono with the inscription on a balloon: “How and why?” McCartney replied:

“How: by signing a document stating that we are thereby terminating our partnership. Why: because there is no partnership.”

According to Paul, Lennon sent a reply postcard saying that if McCartney will be able to get the consent of the others, he will think about it. In the margins opposite these words Lennon quipped: “I expect something a little less ‘poetic’, given that his advisers have been explaining it to him for 2 years.” Then McCartney accused Lennon entered into agreements concerning their joint publishing venture without his consent, to which Lennon objected: “no one can even contact him,” meaning McCartney.

P.S. There is no need to regret what happened, and even more so, many years ago. Without those events, there would have been no individual creativity of all participants and their individual talents might not have been revealed.

The Beatles were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1988)

#the beatles#Yoko Ono#John Lennon#Allen Klein#Paul McCartney#Ringo Starr#1969#music story#music store#music#music love#musica#history music#my spotify#my music#Youtube#Spotify

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dissecting John and Wake’s conversation

Or, at least, a specific section of it. Way before NtN came out, Wake’s specific phrasing when she accuses John struck me as odd. I’ve been obsessing over these lines since 2021.

Given the context, she’s most likely talking about Earth here, not his post-resurrection actions. She is charging him with the genocide of humanity on the day he destroyed Earth. But her language is very specific, and at odds with how Wake usually talks. It sounds rehearsed; it sounds very dogmatic, like another line that has been passed down the generations, just as BoE names are.

According to the HtN glossary, BoE members pick their names from the names of previous Edenites. It goes back all the way to Earth, but they don’t seem to have the context for these references. Wake’s list of accusations against John has the tone of another litany, as if this specific wording has been passed down. John has “heard this ALL before,” which IMO supports this interpretation. He has heard these exact accusations before, down to the wording. They’re ritualised.

Wake recites her charges without any hint of doubt; she’s definitely convinced she IS telling the truth. What I find interesting is the contrast between her very precisely worded charges, and the fact that she follows them up with factually incorrect information. This:

Ok, here’s the thing. John didn’t kill ten billion people with “A” BOMB. Note the singular here. It’s peculiar, because she was SO specific just before, and because this is Wake—she knows her shit about weapons; she would know that it’s way, way more likely to kill billions of people with repeated strikes instead of one (1) huge bomb. And “bomb” it’s not a word that people tend to use in the singular whee they mean multiple bombs. I really think that, given the context, she TRULY means to say that BoE lore has it that John Gaius wiped out all of humanity in one blow. She believes it. This isn’t a historical account; this is a flood myth.

I may be overthinking this, but it’s fun to do it, so. What this conversation says (TO ME, until Alecto proves me wrong etc.) is

BoE believe they know how the destruction of humanity came about.

Their account was probably passed down the generation, and it’s become part of their mythology. It’s entirely not factually correct.

This could be due to simply the fact that it’s been millennia and many records went lost, leaving legends. OR it could be because of other reasons (propaganda?). Also: if we take the apparent (but not confirmed) implication that the non-House planets were settled by descendants of the FTL fleet, there’s the fact that the ships were in orbit while Earth was actually being destroyed—they may have been aware of a bomb exploding as they took off, causing a loss of communication with Earth, but it’s a massive fucking leap from “Melbourne went dark” to “kiwi necro guy killed off all of humanity”. They were already at the edge of the solar system when John “grabbed one” of the ships, but I doubt he was in any way recognisable, you know? It’s more likely he looked like an angry nebula. The FTL fleet would Not know exactly what happened.

(Anyway I’m writing out this because I’m about to start a NtN reread and I remember finishing up my Harrow reread in August and being yet again struck by all the details in this conversation—hence tagging it as #nona reread. Very excited to go obsessing over NtN now.)

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I just picked up a LOT of new followers, I figured a "Hi? Hi! Welcome!" post was in order.

So. Ahem. Hi! I'm Joe, aka "ATOV", aka "Evil Authorlord" according to my readers over on Discord. This is my fandom tumblr, originally and still primarily for the How To Train Your Dragon fandom; my main writing project is "A Thing Of Vikings", which you can find on AO3 (currently available to logged-in accounts only, sadly, due to AI scraping risks).

A Thing Of Vikings is, in essence, the result of a plot bunny that bit down a few weeks after my spouse first introduced me to How To Train Your Dragon. My first comment after seeing the movie was "Cute, but not very historically accurate." Three weeks later, as I was preparing for NaNoWriMo 2016, the plot bunny bit.

"But what if it was historically accurate?"

And that's the central concept of the story. It's an Alternate History story where I take the first HTTYD film and drop it into Real Life History in the 1040s AD in the Scottish Hebrides, and let the consequences ripple out from there.

I try to keep the historical accuracy as high as possible; essentially, despite the fact that I have done my best to integrate dragons into our RL history, nothing changes in the timeline before Hiccup makes friends with Toothless. That's the point of divergence, and boy do things diverge from there.

To say that the story has... grown a bit is a bit of an understatement. It's beefy, with over 150 chapters so far; I recently wrapped up the fourth "book"/arc, and am plotting out Book V, so now is the perfect time to catch up if you're interested.

Also, I have a number of other writing projects, including an original fantasy novel that I am publishing serially on Sundays here on Tumblr, @fractured-legacies.

I hope you all enjoy, and thank you for following me.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

People online refer to Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity frequently. Understandably so! But to understand the idea, it's valuable to not just rely on random people's (often well-articulated and helpful) presentation of their individual understanding of the theory.