Photo

The thing about immortals is that their central conflict has a relatability problem. For everything from Tuck Everlasting to Interview with a Vampire to The Good Place season 4, their driving ennui—that immortality has a downside of severe emotional lethargy—is one that while we can never understand has to somehow be addressed in the narrative.

This is the discussion that The Old Guard circles back around to over and over, with somewhat mixed results: Here is a crew of “immortals,” led by Andy (Charlize Theron), whom we’re led to believe is very, very old. She commands Booker (Matthias Schoenaerts), Nicky (Luca Marinelli), Joe (Marwan Kenzari), and new-arrival Nile (Kiki Layne), as they work to secretly right the wrongs and avoid mysterious powers who target them for their power.

Old Guard is based on a comic book of the same name, but—unlike the studio tentpoles these days—they are not weighed down by the baggage of the property. That leaves director Gina Prince-Bythwood a whole lot of leeway to create something softer, more introspective. The fight is never that far for Andy’s crew, but the movie lets the stunt work be informed by the patient character work happening in between, allowing action to feel more like it punctuates these people’s lives than the other way around. As they sit and contemplate what they’ve done and who they’ve lost, the camera sits close, lingering on the loss that spills over their face. In the end, we are just as delighted to see Andy source a baklava by taste as we are to see her wipe out nameless SWAT members sent to abduct her.

Theron’s ability to kick ass is, by now, well-known. Old Guard has her much more in 1,000-yard-stare, Furiosa mode than zany, Longshot “having it all” frustration. It could be tedious, but she is always balanced in the story—whether by Nile’s outsider perspective, or Nicky and Joe’s florid confession of love for one another.

The crew, like the film, functions like clockwork, always aware of where they have to be even if they can’t quite get there. Their stunt choreography is graphic and well-done (if that’s not too gauche to say in conjunction with each other): we never lose track of who is where, meaning a single falter can speak volumes about a character’s ability. There’s sharp cuts from editor Terilyn A. Shropshire, which alternates the scope between wider action and the intimate drama undergirding the whole thing. With such artful construction, there’s no bloated feeling after so many showdowns; each fight brings new stakes, and never loses steam for the story.

What’s so valuable about the film is how it does all this with a some-what doddering emotional core of immortality. Again, it’s just a hard drum to keep beating in a meaningful way, and the audience is likely to tire of it much faster than they would of actual immortality. But Prince-Bythwood’s direction, married to Greg Rucka’s script allows for a natural rhythm to form, an inhale-exhale of mundanity of their plight mixed with a resolve to do something about it.

There’s not much that will throw you in The Old Guard plotwise, but as art isn’t a puzzle to be solved, who cares if you can see a twist coming a mile away? The important thing is that the motivation feels always earned, that the stakes feel vital to informing the character themselves. It’s a skill that Old Guard never leaves far from its heart or its mind, and so when their credit teaser comes you’ll find yourself wishing that Netflix could just roll you right into the next one.

#The Old Guard#Netflix#netflix film#action#charlize theron#kiki layne#Gina Prince-bythewood#Gina Prince Bythewood#fighting cw#action cw#Greg Rucka#comic book film#pulp diction#review#reviews#films#film#movie#movies#fight choreography#stuntwork#filmmaking#immortality#look it's a solid blockbuster even if you can see it from your couch#watch out#violence watch out

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There is an indelible kindness to Miss Juneteenth. This is not to say it is a film about the ease of life: as we follow Turquoise Jones (Nicole Beharie) trying to prep her daughter Kai (Alexis Chikaeze) for the titular pageant, we see things constantly piled in her way. She has to raise the funds for all the pageant costs and the special dress she wants Kai to wear, her estranged husband’s bond, the power bill. Any step that Turquoise takes is laden with burden, threatening to throw the balance of her world out of whack. So Turquoise does what she always does: she makes it work.

A film with a namesake like that could crumble under the pressure of representing all Black life. But Miss Juneteenth delightfully curtsies at it, choosing instead to narrow its focus on the life of a woman and her daughter struggling to get by. It keeps its story gentle, and its stakes relatively small, but no less important.

While the world of Miss Juneteenth is delicate, it belies a fighter’s edge. Turquoise, we’re lead to believe, has not had the life expected of a pageant winner, working a collection of odd jobs to make ends meet. Beharie is the crux of the film, folding in a world-weariness that is still hopeful for her daughter into every interaction, every moment of solitude. It’s through her that the resilience is gently laced into the fabric of the film, radiating out to the rest of her community: All around her people are finding ways to scrape money together to get a bit of the world that’s theirs. It’s a community that runs on mutual aid, celebrating it even when it can breed individual struggle.

“I just want something that’s mine,” Turquoise says when she turns down a suitor. It’s a galvanizing statement, but Nicole Behrarie speaks it with all the world weariness of knowing that nothing in life comes easy—not pageants, not work, and certainly not ownership of anything. It’s absolutely lovely that the biggest stake of the film comes from the relationship between mother and daughter, struggling to figure out how to connect to each other when they both just want the best. It’s a deeply kind and human perspective that benefits because it refuses any grandstanding and instead just lets the people in the film be.

It’s a confident first showing from writer/director Channing Godfrey Peoples, who gives the whole affair a sincerity that makes it more than a slight slice of life. She allows for moments of quiet in Turquoise’s life, leaving room in the specificity for identification but not judgment. There’s a naturalism to her shots—not only in the way they softly gaze in on the world, focusing on the mother/daughter pair, but in the natural colors, the subdued tone that so much of Miss Juneteenth takes. This is not the vivid desert, nor the Texas of a major city. This is small-town, hard-won Texas, for better or worse. Though Kai and Turquoise’s relationship wrinkles and rankles each other at times, they are a pair, a duo, a team against the world, in sickness and in health.

In the end, Peoples zigs when she could’ve zagged, eschewing either a neat and tidy ending or a predictable blow-up. It is a small slice of life, but it is not unimportant, and Turquoise has finally accomplished her need, if not her want. It’s a beautiful thing to behold, a ray of kindness in a tough, tough world.

#Miss Juneteenth#nicole beharie#channing godfrey peoples#alexis chikaeze#film#films#movie#movies#film review#movie review#reviews#pulp diction#mothers#daughters#mother-daughter relationships#mother-daughter#slice of life#very human and kind and good

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

God may be all around us, but his head of state, the pope, is typically seen from afar. The “supreme pontiff” is tucked away in the Vatican, perched up on a balcony, or else riding around in his popemobile. He is not untouchable, but he is close to it.

“The Two Popes” allows its pontiff no such distance. Director Fernando Meirelles holds the camera in tight on Pope Benedict XVI (Anthony Hopkins), as much a critical eye towards him as it can feel sympathetic towards Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio (Jonathan Pryce), his debate partner (and future pope himself). The former represents a doubling down by the church leadership in the conservative direction. He believes there are to be no married priests, no homosexuals, and preferably every one of his cardinals would speak Latin; tradition uber alles.

The latter is the new guard, beloved and forward-thinking. Benedict isn’t pleased about Bergoglio having either of those qualities, especially not when he was the runner up in the papal election, and now hopes to quietly resign as Archbishop. It’s a move that Benedict worries would undermine his authority, and make his papacy seem even more rocky. By 2012 (when this movie is set) his church has been rocked by the public revelation they covered up rampant sexual abuse, he struggles to connect with those around him and isolates himself for meals. His breathing is labored, next to fit and friendly Bergolio. He feels attacked from all sides.

Even the camera closes in around him. As Bergolio and Benedict banter, it hovers in close up, sometimes erratically zooming in tighter, as if to really back them up against a wall. The only time it gives ground is to place them at even greater odds with their environment—tiny, amongst the natural splendor of Italy; dwarfed by the Vatican’s artwork.

“Two Popes” at its heart is about the way these two men shoulder the burden of those legacies. To Benedict, the church’s role is to be “infallible” in all ways. Bergolio knows that while piety may ennoble suffering, the love of the church is too great a thing to risk with punitive measurements. The fact that both men see themselves holding the line on this makes it that much harder to relinquish any movement. To those who are non-Catholics, it does not often feel like the most fruitful or even necessary discussion; what do we gain by watching church leaders debate stances within Catholicism? Why not interrogate how odd it is to live in a time with two popes?

Sometimes it feels like there is another version of this movie that could’ve been more fun: By the end we have two men, who have both borne the brunt of the papal life, connecting over something as common as a World Cup match. It is a relationship born of mutual respect and understanding, if not agreement. Gone are their long soliloquies that sometimes strain under the weight of the conceit. And after their struggle to connect on anything before (finally landing on “inability to drink coffee late at night”) it is simple.

In fraught times such as these it seems that our divisions matter a lot more than our similarities. Not just across party lines, but within our enclaves as well, a notion “Two Popes” intuitively understands; it is sometimes remarkable how easy it is to find no easy common ground with someone who agrees with you in almost every respect. When we finally get down to the nitty gritty of enacting policy, it becomes more important why we do what we do. Even a slightly different angle can ultimately bring a wildly different trajectory.

In this way, the politicking of the church feels more organic and relatable: Even 2,000-year old institutions struggle with how to hold themselves accountable to those they serve. The differences of the men who would be pope can be found in the small things (their backgrounds, their musical interests), but those ultimately bubble up to inform their whole worldview. Their focus is tight because these are the inches with which a behemoth is turned.

And so “Two Popes” is more intricate than initially meets the eye: What first seems to be implicitly siding with Bergolio’s liberal views—allowing him more moments of open introspection, holding on his face as Benedict pulls out yet another luxury of papal life—is a smoke screen for Benedict’s weary, erudite position. At its finest moments, “Two Popes” interrogates the crossroads these men find themselves at, cornering them in the blinding light of their institution, contrasting them even by the simple colors they wear. They have finally brought these larger than life figures down to men in a garden. These are the moments when “Two Popes” transcends the religious trappings of the thought exercise, or a patchwork of Catholic buzzwords. Whether that peace will also be with you–well that’s between you and your god.

#The Two Popes#Jonathan Pryce#Anthony Hopkins#fernando meirelles#film#films#movie#movies#review#reviews#Pulp Diction#Catholicism#popes#pope#religion#Oscar#Oscars#Oscar movie#Oscar Film#discussions about religion and its direction for a couple hours#Pope Benedict#Pope Francis#Catholics#amirite

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

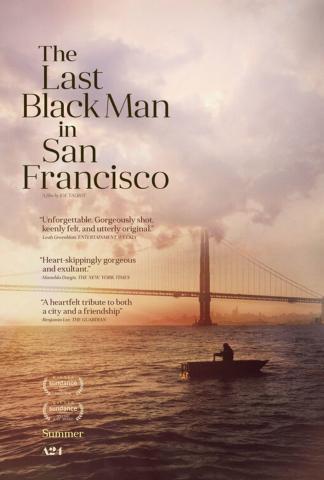

What do you do when your city outgrows you?

That's the question that seems to echo around at the heart of "The Last Black Man in San Francisco," the new film co-written and directed by Joe Talbot.

Talbot takes an odd eye to the site of some of Silicon Valley's biggest disruption; the camera is at times visceral -- like when it gets thrown like a rock on the beach with children -- and at other times leisurely, creating shots that feel more like slow-moving baroque paintings. It is often unhurried and unobtrusive, as if to say that it doesn't matter where the camera is positioned, it would capture the warm, soft light landing exactly right no matter where in SF it was.

Indeed, sometimes that idea seems to be the engine powering the story, following Jimmie Falls (played by Jimmie Falls, who grew up with Talbot in San Francisco, and reportedly discussed this film with him as young as being a teenager) who lusts after the Victorian house that -- as he proudly tells anyone who will listen -- his grandfather built in the 1900s.

The problem is the family doesn't own it anymore. Despite name-checking a few redlining efforts that shaped San Francisco's makeup, like internment camps, "The Last Black Man in San Francisco" isn't concerned with the exact specifics of what drove Jimmie and his family out of the historic Fillmore District; once his family could lay claim to property there, now worth millions, now they can't.

And while that may not be a universally welcomed creative decision, it's a strength of "The Last Black Man" and its storytelling: it softly draws its audience in to a story about gentrification, redlining, changing city streets with heart instead of statistics.

Perhaps no one has made a more lilting love story about what it feels like to feel not at home in your hometown; while numbers are helpful for illustrating a larger story, "The Last Black Man" brings things much closer to home with just emotional punches.

Again, Talbot's camera is key here, catching facial asides after grand statements, or inspecting the house that Jimmie and his best friend Montgomery (Jonathan Majors) eventually repossess, in their own way. In between shooting San Francisco's architecture with almost religious reverence, Talbot and Falls delicately draw connections between how Jimmie at once sticks out and is at home with the city equally angry and fanciful.

As he skates through the city, sweaty and wind-blown, the house itself drips, while the curtains billow out the window. He winds the board down a classically steep hill, comfortably zig-zagging while the cars and trolley around him move perfectly straight. And when he stands on the deck, proudly proclaiming his legacy to a passing segway tour, his clothes match the distinctive color palette of the house. It seems, finally, that he is home at last.

At least, until the green envy of San Francisco real estate comes a-callin'. Ultimately what "The Last Black Man in San Francisco" reminds us is that whether or not your city is a character doesn't matter if it can merely be ambivalent to your existence.

#The Last Black Man in San Francisco#San Francisco#A24#Jimmie Falls#Jonathan Majors#gentrification#gentrify#indie#drama#beautifully shot!#real estate#film#films#movie#movies#review#reviews#Pulp Diction

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Something odd is happening in the town of Centerville: Watches have stopped. Phones aren't working. And the line between fiction and the reality of their world seems to be increasingly blurred.

Someone mentions "The Great Gatsby's wife" when referring to Zelda Fitzgerald, mentioning that Gatsby was "the richest man of the 1920s ... Robert Redford." The film's eponymous theme song plays over the credit sequence, and then on the radio -- something Chief Cliff Robertson (Bill Murray) finds strangely familiar. "Well it's the theme song," his deputy, Officer Ronnie Peterson (Adam Driver) deadpans in response.

There is also the issue of the zombies. In "The Dead Don't Die," writer/director Jim Jarmusch small-town Americana gears up to fight the undead -- which are rising thanks to polar fracking, through a process that's being repeatedly denied by conservatives, but which we're lead to believe has driven the world off its axis -- and they aren't afraid to kick out the fourth wall when they do so.

Jarmusch brings his regular eye toward meandering mundanity to the town, creating a film that wouldn't feel out of place of the "Twin Peaks" universe, complete with stylized dialogue and slow-moving supernatural elements.

As always he finds resonance in repetition: When Robertson gets called to the crime scene of the first zombie attack, he enters, then Peterson enters, then Officer Mindy Morrison (Chloë Sevigny), each with their own take of driving up, seeing the bodies, and coming out.

On a larger scale, that is what "The Dead Don't Die" feels like it's doing: taking a Jarmusch method of adopting a new genre or focus (in this case zombie movies, and the small towns that often inhabit them) and populating it with a collection of stars of both the acting and rock worlds (the stacked cast also includes Tom Waits, Selena Gomez, Iggy Pop, Danny Glover, and Tilda Swinton, as a katana-swinging mortician).

With a cast as vast and prominent as the film's is in a zombie apocalypse, it actually makes it hard to tell who's going to bite it (or get bitten) next. Each actor seems to dive into their roles, having as much droll fun as they can with whatever they're tasked with, without much care about whether it seems like they should be in the same movie or not.

There is a sense that Jarmusch built this one with care; a mantra, oft repeated by a few characters in the film, is: "The world is perfect. Pay attention to the details" -- all but begging the audience to be attuned to the Creepy #71 comic book cited, or the classic horror acoutrement that outfit the gas station. Jarmusch here seems to be hearkening back to the horror of yore.

And yet, the film can also feel a bit toothless. While Jarmusch has embraced his indie status to tackle any number of genres across his 40 years of work, there's not a lot he is explicitly bringing to "The Dead Don't Die" beyond an acute awareness of what "should normally" happen in a zombie film.

His characters know what the zombie "rules" are, much like the teens in "Scream" knew their horror conventions; the zombies here are drawn to what they were craving in life, but that's just a hop skip and a jump from the consumerist zombie parallels of "Dawn of the Dead."

And yet it's still not as simple as saying there's nothing there to chew on; his zombies are slow-moving, but they've got some character, and create a different sort of commentary about what it means for society to eat itself -- the world is, literally, knocked off its axis. What do we do when there are no rules? What do we have left?

The message that Jarmusch drives in on is that of despair, and the difference between giving into the madness and making a last stand. It can sag, or feel a bit hollow, but it's not an empty exercise. Ultimately the movie almost feels removed from whether you liked it or not; as a rumination of cynicism and the end of days, it seems Jarmusch wants us all a little more awake.

#Dead Don't Die#The Dead Don't Die#Bill Murray#Adam Driver#Jim Jarmusch#chloe sevigny#Tilda Swinton#horror#comedy#droll#dry#Jarmusch#review#film#films#movie#movies#zombie#zombie movie#zombies#Pulp Diction#reviews

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life is rarely as simple as movies make it seem. "Late Night" is the first movie in a while to actually understand this.

It's not that it's without some suspension of disbelief: When Molly (Mindy Kaling, who also wrote the movie) finally gets her break in comedy, it comes from the late night talk show host Katherine Newbury (Emma Thompson) pushing her staff to hire a woman ... so that she doesn't look like she hates women.

Never mind that Molly's only work experience is at a chemical plant; Katherine needs a lady to point to in the writer's room, and the movie needs a conceit to get them together.

But "Late Night" also widely understands the shades of bad, and doesn't offer up hollow "you go girl!" moments to defeat them; it's not enough that Molly is funny, "Late Night" knows she still has to work for it, prove herself, and ultimately work with men who have their own flavors of misogyny.

The film definitely gives Molly the opportunity to clapback at the men and prove herself -- "I'd rather be a diversity hire than a nepotism hire. At least I had to beat out every other woman and minority to get here. You just had to be born!" -- but it also shows her putting in the time to improve herself independent of them.

And thankfully the movie doesn't just stop at them: Emma Thompson's Katherine Newbury is not a nice person, nor is she even a particularly kind person when you get down to it. She expects the best of herself and those around her, and after decades in her position it's become a little hard for her to tell well-thought-out advice from the sexist bullshit she breathes in and out every day. They manage to toe the line of a truly horrendous boss who is not irredeemable or without self-reflection.

The narrative allows for the flow of perspective, fault, and reasoning so that there's no "right" answer or take on the situation; delightfully, everyone in "Late Night" is doing their best, flawed as they may all be.

That lets "Late Night" not just be smart storytelling, but a smart re-thinking of things that have often felt too hard to feel fresh with, like affirmative action and comedy itself. We completely follow Katherine's paralyzing fear that making her comedy personal would be a line she couldn't uncross -- and that's ultimately a far more complex question to ponder with your narrative than "is comedy political?"

"Late Night" also ends up really being a feat: It's sharp and funny in both in its comedy and its dialogue (Thompson never seems to miss when she's eviscerating her subject, casually or otherwise).

It would've been easy for either Kaling or Thompson to turn in simple performances, but together their characters revel in the nuance of their situation. They have their characters down to the smallest details, letting their clothing speak volumes about their evolution. And as a life-long performer, Thompson understands the subtle little tics that make up the command of an audience a late night host must handle, adding reality where she didn't have to.

The film may not be perfect -- there are some shortcuts taken, like the job connection or Katherine's marital situation -- but the film seems aware of those, or at least game to play around them. They know that it's not so simple or easy to just suggest the changes to the culture, they need stepping stones that keep the work alive.

In short: "Late Night" is more than ready for prime time.

#Late Night#Emma Thompson#Mindy Kaling#comedy#workplace#rom-com#sort of!#mentors#comedian#culture#movie#movies#film#films#Pulp Diction#Review#reviews

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Dark Phoenix" arrives in our world at a bit of an odd time.

Just after Disney acquired 20th Century Fox, thus giving them the ability to include the X-Men franchise in their greater Marvel Cinematic Universe; a good chunk into our modern superhero film era, when superpowered protagonists are the juggernauts at the box office; not too long following the movement in Hollywood to recenter women in their narratives, and reexamine stories we thought we knew.

And "Dark Phoenix" would seem to be an interesting addition to this cultural moment: After Jean Grey (Sophie Turner) gets hit by some sort of massive star power in space, she begins to lose control of her powers and uncover traumas buried in her past. As she becomes increasingly untethered, the rest of the X-Men -- including Professor X, Magneto, Cyclops, Storm, Beast, and Mystique -- have to find a way to bring her down, one way or another.

And yet, "Dark Phoenix" doesn't seem to be all that interested in the emotional stakes of the story. As the X-Men are wont to be, the film is filled with pathos as it explores the fallout of Jean's actions. But for a film that's so dour, it's not really engaged enough with its drama to ride the wave; the X-Men are once again sucked into a conundrum of whether humanity will accept them or not, and what this latest knock-down drag-out city-busting fight will mean for said acceptance.

Essentially nothing has changed in the X-Men universe: the Mutants still stand-in for a civil rights battle without having updated the focus or rhetoric by which they argue; the cops still show up and employ drastic measures to contain them; and ultimately it all comes down to a super powered woman who could explode at any moment.

In a time when we are rethinking our approach to women's narratives that we thought were done to death, it's a shame to waste Sophie Turner of all people in a story that's ultimately more interested in exploring the feelings and machinations of the men around her.

Especially when it once again squanders the talent around it: While Michael Fassbender's Magneto gets an almost Shakespearean moment to take in the announcement of a death in the family, and Beast (Nicholaus Hoult) and Xavier (James McAvoy) grapple with their changing approaches to Mutant rights, the big bad -- Jessica Chastain as an alien shapeshifter hunting Jean down -- is devoid of any emotion.

Chastain and Turner both turn in strong performances with what they have. Turner, completely overwhelmed internally, bridges the dime-turns she does from shattered to invulnerable (as one of the most powerful Marvel heroes; Chastain is blanched of melanin, passion, or doubt in her mission.)

But when so much of the film is about the rest of their team reacting to the power of these two women, papering over their motives or goals or changes of heart, it ultimately re-treads a lot of ground already covered by the MCU.

Jean Grey, as we can see, is special. "Dark Phoenix," not so much.

#Dark Phoenix#Jean Grey#X-Men#Phoenix#Magneto#Beast#Professor X#Xavier#Sophie Turner#Michael Fassbender#Nicholaus Hoult#James McAvoy#Jessica Chastain#Cyclops#Storm#feminism#MCU#Marvel#comic book movie#comic book#film#films#movie#movies#comic books film#comic books#superheroes#super women#Hollywood#review

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Much like the pets in the title, "The Secret Life of Pets 2" is about as cute and a bit more than you might expect.

As we follow our band of merry critters through their various adventures -- which include overcoming anxiety and self-doubt, visiting a farm (not a euphemism), springing a tiger from captivity, and rescuing a prized toy from an apartment just filled with cats -- it would be easy to just sort of tune out and let them do their things. This is, basically, "Toy Story," but about your pets; they're cute, they're fluffy and they do zany, fantastical things when you're not looking.

But "Secret Life of Pets 2" almost never plays it easy. With plots loosely threaded through vignettes, it's pretty much always zipping along as if it's a long episode of television, separating characters into their own timelines before bringing them together.

It helps make the film feel less beholden to the sequel machine that no doubt at some point shared some responsibility for its greenlight, and instead lets kids just see some of their favorite animated animals just hang out. (It is, in that way, the antithesis of something like "Dark Phoenix," which unsuccessfully circumvents all the fun of seeing your favs come together and bounce off each other.)

And it doesn't overplay its hand, either: the villain -- a cruel circus owner -- is truly nefarious, but the stakes remain relatively low and controlled (at least, as much as an escaped tiger and a hijacking of an old lady's car via feline prowess can be).

That strategy can no doubt make "Secret Life of Pets 2" not quite as ambitious as other children's fare is, when it's at its best; they're not exactly swinging for the fences here.

But ultimately it helps the movie zig when you think it could just zag: the Shih Tzu turns out to be pretty good at action, while that dark recess of the cat lady's apartment holds even more deranged felines than you'd expect.

No doubt those moments will delight kids, but in my (packed) screening it was children and adults a like who were laughing.

There are definitely some weird animation stereotypes afoot -- when even the evil wolves have pointedly big noses and accents, it's not a great look -- but just like its cat-in-training Gigit, ultimately "Secret Life of Pets 2" lands on all fours.

Plus, Harrison Ford as a Welsh sheepdog plays about as well as you'd expect.

#The Secret Life of Pets 2#Pets#Secret Life of Pets#Jenny Slate#Harrison Ford#Patton Oswalt#Tiffany Haddish#Lake Bell#Kevin Hart#Dana Carvey#comedy#kids#childrens movie#childrens movies#pet#secret life#animated#animation#shih tzu#bunny#cartoon#dogs#cats#movie#movies#film#films#review#reviews#Pulp Diction

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you watched Joanna Hogg's latest drama, "The Souvenir" with no other knowledge about it you might be inclined to think that Hogg stays removed from her protagonist out of a lack of intimacy.

Hogg's camera remains at a distance from Julie, the film student lead at the center of the film in the 1980s. We see her charmed by her life: working on assignments for school, talking frankly with her mother, in a sort of salon with her friends. But there are limitations on how deeply we can probe – the camera often holds at a steady distance, not letting us see the content of letters that make her smile or arguments that make her cry.

It's in this space, at this distance, that Hogg balances emotional resonance and a cerebral framing, loosely hung together as a series of memories almost, tracing Julie's relationship with Antony -- an older man who claims to work at the state department, and definitely has a problem with addiction.

"The Souvenir" weaves their complicated tale back and forth, hazily building a love story out of these fragments of their lives. New furniture appears, mirrors get broken, pillow talk gets had; it's not always clear what Hogg expects us to get out of these, but it certainly feels like we're dropping in (and out) of intimacy.

"We don't want to see life played out as is," one character tells another. "We want to see life experienced."

Which is, ultimately, what "The Souvenir" is: Hogg based the drama on her own life, her "own Antony," and her own memory.

It is perhaps what gives the movie such a lightness in feel, even as the subject matter becomes almost too weighty to stand without some sort of resolution; there's a vast network of ideas, an entire world that seems just beyond our grasp or control. It's catching wind of a friend's serious moment through half-told anecdotes.

Honor Swinton Byrne and Tom Burke, who play the couple in question, instill so much meaningful fragility in their dynamic. Swinton Byrne's Julie is so often quiet, inquisitive, and full of self-doubt, but around Burke's standoffish and snobby aggression she becomes a new character, dressing more like a school girl and less in her masculine style than usual.

Together they build a love that feels weathered, far from perfect, but scrumptious in its quiet devotion. Though the story at the heart of "The Souvenir" has been told before, it feels as if a viewer could listen in on their intimate moments forever. Which is what makes the film's sparse fragments so tough to handle.

#The Souvenir#Joanna Hogg#Honor Swinton Byrne#Tom Burke#Tilda Swinton#love#relationships#film#films#movie#movies#review#reviews#Pulp Diction#beautiful but sparse#drama#romance#romantic#Souvenir#addiction cw#watch out#drug use watch out

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

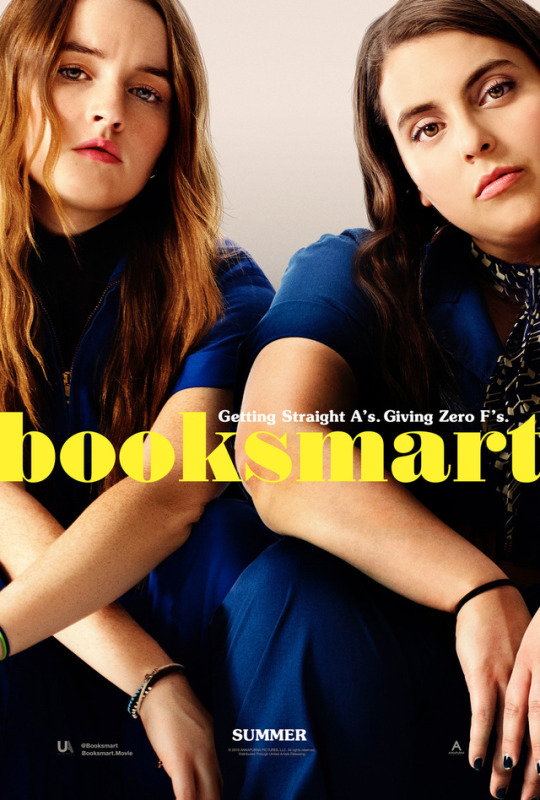

The best thing about "Booksmart" is how you never doubt that Molly and Amy, the high school best friends and overachievers with a superiority complex, are going to be OK. The fun part is everything that happens along the way.

We follow them through their last day of school, and quickly glean how self-assured they are, always looking forward to what is sure to be a life full of excellence and feminism; sure, they're better friends with their English teacher than they are with any of the other students, but at least they're going to the best colleges, right?

Only then a confrontation with the popular kids reveal to them that though Molly and Amy skipped all the typical high school antics in favor of a single-minded focus on getting into good colleges, their slacker counterparts got the same grades, and got into the same Ivy League schools.

And so the duo -- played with aplomb by Beanie Feldstein and Kaitlyn Dever -- decide that they'll attend the graduation-eve party, get smashed and close the book on high school with at least one rowdy story for the history books.

That plot is something you've seen before (not least of which in "Superbad," which stars Feldstein's brother Jonah Hill), but first-time director Olivia Wilde's style breathes life into the frenzy of adolescent girlhood on the cusp of change.

Moving frenetically through quick set pieces with verve and positivity, Wilde takes care to make sure her heroes are modern nerds, underscored with deep love and zaniness. They are ruthlessly ambitious and obsessed with things they can't connect with their classmates on, not just bespectacled, un-cool kids.

It allows Feldstein and Dever to revel in their un-coolness, throwing themselves into their night-long odyssey with the same ferociousness as their characters. They obsess over each other's crushes, attempt to out compliment each other, invoke "Malala" as their "we're going to do this" code word; they may be ostracized by their classmates, but they hardly notice.

Wilde treats their life like a zany madcap, complete with a mixtape-esque soundtrack that drops the needle for seconds at a time before abruptly changing pace. It can feel a little tiresome, at times, but it allows "Booksmart" to dramatically shift gears, and becomes a key table-setter for the climax later on.

It would've been one thing for the movie to pivot around Molly and Amy's wacky sensibilities, using them as a prism for life around them. Instead "Booksmart" populates the entire world with characters on their same level but in their own bubble of the world: There's Skyler Gisondo as a boy desperate to be cool, or his best friend Gigi, played with exquisite chaotic neutral energy by Billie Lourd.

Even the popular kids who deride them and their genuineness about school feel lived in and full, complete with a new (and much more realistic) take on the "cool girl" played by Molly Gordon.

Over and over again, "Booksmart" seems to take the tropes and situations that overpopulate teen movies, and deepen them without cutting them entirely. Just because these girls don't yell at people about "Game of Thrones" on the internet doesn't mean they're not the ostracized nerds of the school, and just because the popular girl has sex when she wants to doesn't mean she didn't get a high score on the SATs.

And by reforming these high school archetypes with care, Wilde has managed to make a film that feels wholly new and also for the ages.

Even when the two have to say goodbye -- high school can't last forever -- the film feels comforting in a way that's nearly unparalleled by the high school comedies that came before it. Their goodbye will be a hard jolt out of the cocoon they've lived in with each other for (at least) the last four years. But we know they're going to be OK. And after a screening of "Booksmart," we know we're going to be OK too.

#Booksmart#beanie feldstein#Kaitlyn Dever#Olivia Wilde#indie#comedy#coming of age#skyler gisondo#Billie Lourd#teen#teen comedy#graduation#romp#i completely loved it#high school#Molly and Amy#Pulp Diction#review#reviews#film#films#movie#movies

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Lord of the Rings" isn't just a household name. The series twice broke expectations: The first time when author J.R.R. Tolkien released the books, starting with "The Hobbit" in 1937, they were met with widespread acclaim. When Tolkien attempted to create an English mythology with "Lord of the Rings," it was hailed by some as "among the greatest works of imaginative fiction of the 20th century," and revitalized the fantasy genre.

It next broke expectations when Peter Jackson adapted the series into a trilogy of movies, whose sweeping epic broke box office records, became a Best Picture winner at the Oscars, and changed the game for fantasy movies.

Both of these works required immense thoughtfulness and care; despite emulating things that had come before, they built something new and utterly fantastical. They were game-changers.

But "Tolkien," the new biopic about the man behind the legend, takes no such leaps of faith. And while this doesn't necessarily make it a bad movie, it does ultimately feel like a missed opportunity.

Tracing the life of John Ronald from childhood (played, in adulthood, by Nicholas Hoult), through forging friendships at prepartory school, falling in love, going to war, becoming a professor, "Tolkien" seeks to fill in some of the gaps of Tolkien's life.

Along the way are some nuggets that we're lead to believe would ultimately inform the work he's most known for — his constant imagining of languages, or when his best friend chides his love of "The Ring Cycle" by stating, "it shouldn't take six hours to tell a story about a magic ring."

And though the story jumps around through time, complicating its narrative somewhat, you've likely seen a movie like any version of any timeline: The man fighting to find his friend on the front lines; the forbidden love story between those at different stations; the fellowship of young boys on the uppercrust of British society.

Each of these storylines draws cliches from their own narrative tract, and those sting of that doesn't necessarily go away just because the plotlines are mixed around. Sometimes "Tolkien" can feel a bit too neat as its story circles around the same ideas, haunts and words throughout the man's life.

That said, it's hard to knock the film for being simply an earnest and well-produced dramatization of J.R.R.'s life. Just because it's staunchly hemmed in by adherence to typical artist biopic or war movie rules, doesn't mean that there's not fanciful set design and some real meat to the friendships deepening through thick and thin.

It's there that, when the movie isn't having Tolkien see dark lords on the battle field, that "Tolkien" makes its best case for portraying the creator of "The Lord of the Rings." The work he produced was once in a lifetime, even if his biopic isn't quite there.

#Tolkien#nicholas hoult#lilly collins#JRR Tolkien#J.R.R. Tolkien#JRR#Lord of the Rings#LOTR#biopic#drama#period piece#film#films#movies#movie#Pulp Diction#review#~fine~ really#exactly what you'd expect probably

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

With every new gender-swapped remake comes the question: Is this worth it?

This is not to ask whether women-lead movies earn their spot (they do), but rather whether it's worth it to just re-hash established properties but with women instead of men, instead of just providing them with new works actually built around them. Sure, lady James Bond might be a lot of fun, but there's also "Killing Eve" which checks a lot of the same boxes while also being more focused on craft rather than the old mantra of "backwards and in heels."

And so, so many gender-flipped comedies took leaps to build out new characters within the world of the IP: "Ghostbusters" built a re-imagining into their world; "Ocean's 8" made Sandra Bullock the sister of George Clooney's Danny Ocean.

Enter, "The Hustle," which takes us back to the sun, opulence, and power battle for the French Riviera village of Beaumont-sur-Mer previously visited in "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels."

The movie is a beat-for-beat remake, only this time instead of Michael Caine and Steve Martin, it's Anne Hathaway and Rebel Wilson as two competing con artists who make a "loser leaves town" wager to see who gets control of Beaumont-sur-Mer: The first to swindle app creator Thomas (Alex Sharp) out of $500,000 wins.

Like "Ocean's 8" before it, "The Hustle" laces in some "feminism" — or at least recognition of life under the patriarchy — that prompts the characters to turn to and excel in a life of crime. Which "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" fans would know sort of takes the gas out of certain parts of the film, leaving a slightly bitter tang to the "girl power" fuel of the film.

The film is, thankfully, funnier than you might expect: Rebel Wilson's schtick is largely well-employed for the role of the more boorish con artist Lonnie. Anne Hathaway is all in on whatever her sophisticated Josephine has to do to pull off the heist, breathing charm between a cache of accents.

Both are all-in on their personas, and while Hathaway's may be a bit more in line with her predecessor and the two never really find a chummy chemistry the way their "Scoundrel" counterparts did, they're rarely not fun to watch.

So it's a shame that as the movie wears on the note-matching becomes a bit tiresome, even as the swap becomes cannier (surely anyone can tell you that the only thing more fearsome than Navy men looking out for one of their own is a group of women who retreat to the ladies' room to plot).

And though Sharp is very adept at playing a gullible tech millionaire, Glenne Headly makes an indelible impression in "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" — a presence the film sorely misses, as it turns increasingly to the con artists themselves.

Ultimately everything is lightened by the easy, breezy world of con artists in the French Riviera. It's not quite as clean as its forebears ("Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" is, after all, a remake of the 1960s' "Bedtime Story"), but it's still a lot of fun to watch -- just because a scam is obvious, doesn't mean it doesn't work.

#The Hustle#Dirty Rotten Scoundrels#Anne Hathaway#Rebel Wilson#Beaumont-sur-Mer#remake#gender swap#Alex Sharp#comedy#film#movie#movies#films#review#Pulp Diction#movie review#film review#can't quite bilk everything out of those Dirty Rotten Scoundrels#but it's solid

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

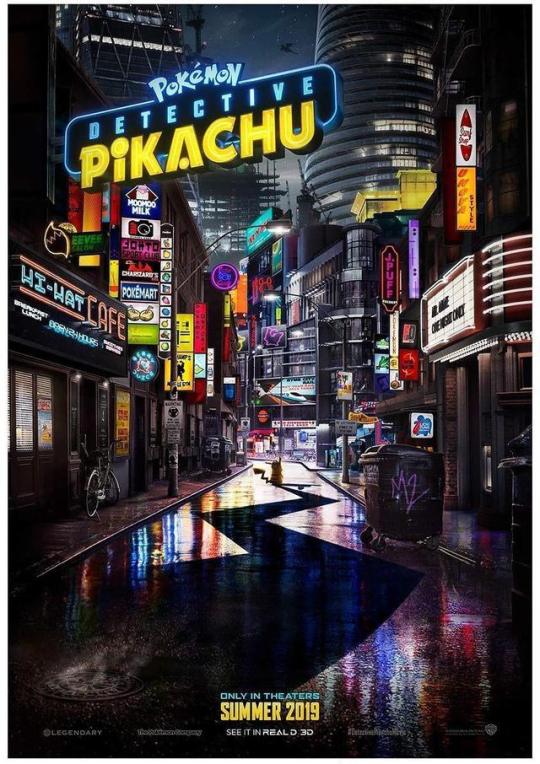

The Pokémon universe has seen a number of renderings over the years, but we've never seen one quite like "Detective Pikachu."

Obviously the movie is based on the game of the same name. And yet, "Detective Pikachu" the film manages to create something wholly unlike any Poké-property we've seen before -- yes, the Pokemon are vividly rendered, but so are many of the other aesthetics. The same care that brings every hair follicle to life on Pikachu's body (so realistic it's easy to forget a time when you might've thought that Pikachu was not a hairy creature) also brings pops of rain-soaked neon, or dynamic countryside that hides dangerous secrets.

It helps propel the movie's "noir but for kids and their Pokémon" plot along: Tim (Justice Smith) and his partner Detective Pikachu, are looking for Tim's police detective father, who went missing around the same time Pikachu lost his memory.

The film is exactly the kind of marriage of silly and serious that you'd expect with a logline like that, with the duo encountering everyone from idealistic tycoon who believes that Pokémon and humans can live together (Bill Nighy), and an unpaid journalism intern who thinks there's more to sniff out in the underbelly of Ryme City (Kathryn Newton).

Winding a seedy mystery within all of this earns "Detective Pikachu" some comparisons to "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" which also melded cartoon and human characters trying to untangle a web of lies. Though that film is a bit more connected to reality, it's hard to knock "Detective Pikachu" for staying focused on having fun with all its Poké-players.

After all, it's got a wealth of material to pull from, a whole world to build out. And beyond a few flashier call-outs to the greater Pokémon universe, it's fairly entry level, allowing fans and non-fans alike to let the narrative pull them along.

And unlike other movies released this weekend, "Detective Pikachu" is rarely there to goad your emotions along. Just twice does the music really swell and let Tim (Justice Smith) and his partner, Detective Pikachu (Ryan Reynolds) take an emotional beat and cry.

Beyond that it's having fun flexing its players in ways they know best -- whether that's a PG-appropriate version of Reynolds' motor-mouthed act, Newton and her Psyduck being utterly gung-ho even when they're a bit flustered, or letting Nighy put mendacious, Shakespearean spins on words like "Pikachu."

Sure, it's not perfectly tight, nor is the dialogue always inspiring (Tim and Pikachu are always there to explain what we just saw, for better or worse). But the mystery at the core of the film is fun, and has a knowing edge to it about just how ludicrous it would be to take this whole thing too seriously. It's just the right concoction of understanding the stakes without forgetting the laughability of noir around Pikachu as a detective.

Plenty of dramatic reveals are in store, but rather than dumping on what is "predictable" or not (already a boring concept that often takes for granted any fun the film), it's more apt to say that the conspiracy has many moving parts that allow Tim and Pikachu to stay right on top of, like a rolling log.

And ultimately the mystery doesn't matter as much as the friends they made along the way; "Detective Pikachu" is at its most fun when it's got a hit of madcap comedy and a strand of mystery guiding the way, but its adept ability to balance all the things it has going isn't nothing. At the very least, it's charming to watch a Pokémon universe come to life, without letting all the Poké-madness keep it from being a universal watch.

#Detective Pikachu#Psyduck#Pikachu#Detective#noir#mystery#comedy#action#blockbuster#Ryan Reynolds#Justice Smith#Kathryn Newton#Pokemon#Pokeball#film#films#movies#movie#review#film review#movie review#Pulp Diction

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

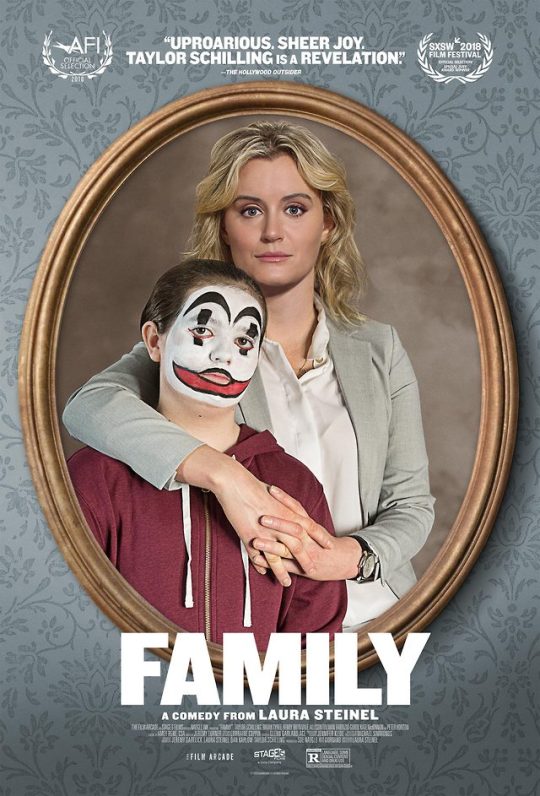

The thing about good comedic actors is that they really have to sell the horror of their situation. If you follow the saying "horror is just comedy without the punchline," then excellent comic actors have to sell the horror and then sell the punchline. The jokes are funny because they are taking them seriously.

That's the magic behind "Family," which sort of disingenuously presents itself as the story of an aunt whose high-pressure work-focused life is thrown into disarray when her niece decides to become a juggalo, or a fan of the Insane Clown Posse.

The actual logline — a workaholic aunt is tasked with babysitting her niece for a week, during the course of which she discovers the Insane Clown Posse — is not quite as flashy, but the result feels a bit more true. Especially when "Family" has delightful and easy chemistry between Kate (Taylor Schilling) and her niece Maddie (Bryn Vale).

It's the curse of "Family" that its story is something so tried and true, when the movie itself feels inventive and full of energy even when it's walking through well-trod territory. Whether it's Kate's speeding and abrupt stops in her luxury car, or Kate McKinnon as the neighborhood mom who is just trying to get Kate to think about the kids (and close the garage door), "Family" ekes a lot of legitimate laugh out loud moments as Kate struggles to make it through the week.

It's one of the biggest strengths of "Family" that it routinely puts Kate in conversation with these players, placing her on a continuum of terribleness as opposed to an island of one.

Whether it's the cutthroat sexism of her office (which Kate herself plays into) or Maddie's mom's refusal to meet her daughter where she is, Kate's inability to recognize the trials of raising kids until she's tasked with it is just an extension of the good and bad energies we all face.

The dry and quick humor resembles that of a office sitcom, with a cast of characters that each have their own thing going on. Perhaps most delightfully, none of them ever pull their punches or their punchlines, committing just as thoroughly to the escalating horror of their situations as they do to their jokes.

You may not be able to pick your family, but "Family" is worth a pick for a screening.

#Family#Taylor Schilling#Kate McKinnon#Bryn Vale#comedy#movie#movies#film#films#film review#review#movie review#Laura Sentinel#smart!#fun!

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There are times during "Teen Spirit," the directorial debut of actor Max Minghella starring Elle Fanning, that feel almost like you're watching a visual album more than a movie.

Whether it's the aloof way the film refuses to spell things out, or how every moment on stage feels more like a well-edited music video than a musical interlude, "Teen Spirit" seems less connected to its narrative than it maybe ought to be.

It's not necessarily a bad thing: Following Violet (Fanning) on her rise from morose teen to serious player on a reality show singing competition, the actual story of "Teen Spirit" is relatively slight.

And so the movie gets most of its energy from its players -- Violet's ability to let the music consume her, or her "manager" Vlad (Zlatko Burić) and his wry humor. Minghella (who also wrote it) lets every actor perform at their own tenor, even in scenes where they all come together to discuss Violet's future, meaning they can coalesce into the same world but still bring different moods to the film itself.

Which is good since no matter how good Fanning is at communicating by just having Violet stare wide-eyed at the world, this movie flits by a bit too simply. There seems to be nothing that "Teen Spirit" loves more than building a world around its teen sensation through a montage, rather than letting the story just speak for itself.

Still, if you can ignore the slightness of the narrative and get on board with the '80s, synth-heavy atmosphere, there's a lot of loveliness to "Teen Spirit." At its best, the film's ability to err on the quiet side of stardom ends up with some poignant peeks behind the curtain of star-making -- and some relatively kick-ass musical numbers.

#Teen Spirit#Elle Fanning#Zlatko Buric#Max Minghella#Films#film#movies#movie#Pulp Diction#review#drama#music#coming of age#sort of#slight but spirited#pop stardom#pop songs

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All’s messy in love and war in “The Aftermath.”

You have likely seen "The Aftermath" before: Beautiful people, in beautiful period clothes, navigating a world ravaged by war and emotions that flow through them like a lightning strike.

In this case it is Rachel Morgan (Keira Knightley), who has recently arrived in the ruins of Hamburg to be with her husband, British Colonel Lewis Morgan (Jason Clarke) when he is tasked with rebuilding -- and uniting -- the city after the war. She's stunned to find that they will be sharing the grand house he's occupying with the previous owners, including handsome German widower Stefan Lubert (Alexander Skarsgård).

And so "The Aftermath" weaves a tale about the messiness of war, and the even messier post-war aftermath, as panic and grief give way to passion, betrayal, and a new world order. As Hamburg struggles to reconcile its war years with its modern occupation, so too do Rachel and Stefan navigate a growing attraction to each other.

Though the movie is riddled with obvious visual metaphors -- Stefan's daughter replacing Rachel at the piano, or the simple opening of a curtain to let the light in on a torrid affair -- there's something neat to the way the movie throws itself into the convoluted melodrama of post-war recovery.

Nothing is simple, and though this movie is familiar it's not a carbon copy. This love triangle does what all good ones should do: place the person in the middle between two options, neither of which is the "easy" answer.

That sort of thing is typically easier said than done in love triangle literature, but it's also the sort of thing that requires strong performances, which is what helps float "The Aftermath" even in its more pedestrian moments.

Knightley and Skarsgård have mastered the yearn, creating an ache between them that fills up any gap left by the script; as they smolder at each other it almost feels like they've created an entirely different film for themselves.

Clarke and Flora Thiemann (who plays Stefan's teenage daughter flirting with a German Nationalist) both have plotlines that are a bit too clipped, but their performances give the impression that this story could be stretched out into an entire season of television.

"The Aftermath" is, at its heart, a romance about the affair, something that has been told across decades, wars, and styles. But the movie mines a bit deeper than that (not much, but some) to find something engaging about how narratives are never neat -- not even something typically presented as clear cut as World War II.

That's not to say that everything in the movie isn't too neatly shut down -- the aformentioned side-plots trace back to the main plot, but ultimately feel a bit hastily drawn. But even at its lowest, "The Aftermath" is innately watchable, thanks to the performances and glowing shots captured by director James Kent and cinematographer Franz Lustig.

And so "The Aftermath" occupies a strange sense of feeling better than the version you've seen before, without necessarily perfecting the concept at all. It's messy and engaging, just like the aftermath of almost anything.

#The Aftermath#Keira Knightley#Jason Clarke#Alexander Skarsgard#Flora Thiemann#James Kent#Franz Lustig#WWII#World War II#post-war#melodrama#romance#romantic#drama#period piece#review#pulp diction#film#films#movies#movie#reviews

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Hotel Mumbai" is a sort of double-edged sword of films. Following a real attack by terrorists, who killed more than 160 people in assaults across Mumbai, the film hinges on its ability to turn a real-life tragedy into a thriller that has you on the edge of your seat.

Which means that the more the film succeeds in sucking you in, the more distanced you feel from it, with an on-going queasiness in the pit of your stomach.

It takes the "Crash" approach to the event, following characters from around the world who have the misfortune of being in the luxury Taj Mahal Palace and Tower hotel when the gunmen arrive.

If you're knowledgable about the November 2008 attack, then you know that 30 people died in this hotel alone, meaning any of the cast you see on-screen is in harm's way, whether it's the affluent couple and their baby (Nazanin Boniadi and Armie Hammer), the Russian business tycoon (Jason Isaacs), the Sikh waiter who's got a baby on the way (Dev Patel) or his boss who barely let him work that day anyway (Anupam Kher).

There is, indeed, a knowing precision to the way these lives get interlaced, crossing each other in ways that are both tense and gripping. Sure, it indulges some cliches of the genre, but there's a sense of alarm that soaks into every moment the hotel is under siege.

But ultimately, it's all in service of a goal that's questionable at best and straight up wrong-headed at worst; by reducing the randomness of a real-life tragedy for slick thrills feels callous, especially when the only real interrogation of the gun violence the movie has is to portray the terrorists with a growing self-awareness of how irrational their mission is.

Whatever quiet radical look at how sometimes the person who saves your life might be your scrawny server -- "The guest is God," the hotel staff is warned at the beginning of the film before knowing just how far they will be asked to take their role -- is dwarfed by the problematic (and largely unmentioned) note of turning a recent tragedy into a thriller. The problem is "Hotel Mumbai" can be hard to watch, and possibly not for the reasons the filmmakers intended.

#Hotel Mumbai#Nazanin Boniadi#Armie Hammer#Dev Patel#Jason Isaacs#Anupam Kher#thriller#action#based on true story#cw terrorism#cw violence#cw guns#cw death#cw#watch out#guns watch out#violence watch out#terrorism watch out#death watch out#questionable optics on this one bbs#islamophobia#terrorism#islamophobia cw

7 notes

·

View notes