#muscular dystrophy

Text

#disabled#lesbian#disability#queer and disabled#chronic disease#disabled lesbian#muscular dystrophy#wheelchair user#severe disability#friends#chronically ill#wheelchair#idk why i vent on here and not my other social media’s

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

while me post most about nonverbal nonspeaking because intellectual/developmental disabilities, here something about become nonspeaking after/because medical crisis in 2022 & tracheotomy & muscular dystrophy, by alice wong.

overview: “This is a 2-3 minute audio letter to the late David Muir, a disabled man who invented the Passy Muir® Valve, an attachment that enables people with tracheostomies to speak. As a newly nonspeaking person, this letter allows me to share my thoughts on the desire to speak and reflections on silence.”

I paused to consider the phrase “dignity through speech.” There is dignity in silence too. Silence does not mean a person is voiceless, as there are millions of nonspeaking people who use gestures, sign language, writing, technology, and other means to communicate with the world.

I live in a world of silence that is not lesser or devoid of richness. My reality is just different. Silence forces me to be more thoughtful and intentional in considering what I want to say and how I say it when I type into my speech-to-text app, which listeners to this letter are hearing now.

…

The worlds of speech and silence intersect and overlap. Silence isn’t static or limiting. Silence is not an empty void. Silence has a landscape of its own. Silence has its own dimension, a space that enables another way of thinking and being. There is dignity in all forms of communicating.

#nonspeaking#actually nonspeaking#muscular dystrophy#tracheotomy#loaf screm#disability#actually disabled#cripplepunk#cripple punk

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y’know at this point I kinda don’t care if I drive people away with this.

I have a right to talk about my disability, and how much I hate it.

I’m tired of dealing with it. And I’m constantly uncomfortable with it.

It’s hard to live a fully happy life if your physically in discomfort almost all the time. It’s hard to be happy when you can’t do almost anything.

It hurts. It’s tiring.

#muscular dystrophy#merosin muscular dystrophy#disability#disabled vent#disabled#cripple punk#cripplepunk#sad cripple#physically disabled

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marilyn Monroe with 12 year old Donald Thompson, a boy who suffered with the condition and to whom she donated to at the “1955 Thanksgiving week March of Muscular Dystrophy” in New York on November 17, 1955.

#marilyn monroe#donald thompson#1950s#50s#1955#vintage#retro#Old Hollywood glamour#old hollywood#history#photography#1955 Thanksgiving week March of Muscular Dystrophy"#muscular dystrophy

757 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

#palestine#free palestine#israel#free gaza#gaza strip#direct help#helpkhaledevacuate#gaza#boycott divest sanction#please share#help#evacuation#muscular dystrophy#free palestine 🇵🇸#news#bds#fypシ#instagram#savegaza#please help#reblog plz#khaled#🍉🇵🇸#♿️#disability justice#wheelchair user#help gaza#🇵🇸🇵🇸🇵🇸#from the river to the sea#save a life

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

104 notes

·

View notes

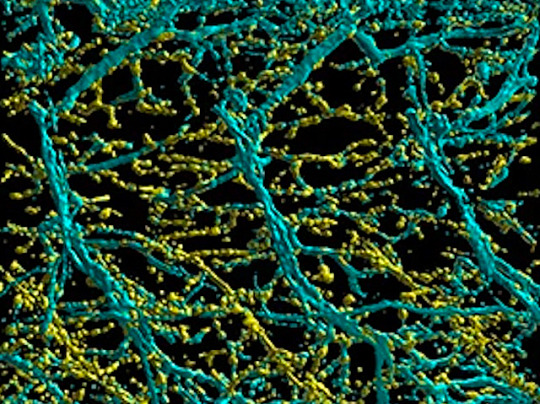

Text

Muscle Differences

Zebrafish model reveals molecular differences between muscle types affected and unaffected in muscular dystrophy – Fhl2b protein has a protective effect with potential for therapies

Read the published research article here

Image from work by Nils Dennhag and colleagues

Department of Medical and Translational Biology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Image originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Published in Nature Communications, March 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is the first gene therapy approved to treat this debilitating and fatal disease found almost exclusively in boys.

Emma Ciafaloni is a neuromuscular neurologist with the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) neurology department and Golisano Children’s Hospital, and director of the UR Medicine Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Clinic, which treats boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) from across upstate New York.

Ciafaloni has been involved in DMD clinical research for decades and URMC was one of first three sites in the nation to start dosing patients in the phase 3 clinical trial for the new gene therapy. The study, called EMBARK, has since expanded to additional sites in North America, Europe, and Asia. Ciafaloni also served as chair of the independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board for the early phase clinical trials of the therapy. The new drug—delandistrogene moxeparvovec-rokl—is being developed by Sarepta Therapeutics and marketed under the name ELEVIDYS.

Continue Reading

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

the disability pride flag! It’s not disability pride month, but I felt a little disability pride is in order for all the disabled folks who feel like they aren’t enough. YOU ARE DOING AMAZING!! Despite all capitalist, ableist, racist, queerphobic, fatphobic obstacles in your way, you are still alive and doing what YOU need to do in order to live. That’s pretty badass. People, and oppressive systems don’t expect you to be proud, or happy, because when you’re disabled, it’s supposed to be tragic and sad. Well you are not tragic, or sad, or anything else these people who know nothing about you say you are. Being proud and disabled is an act of rebellion against these oppressive systems that we are forced to live under. I’m very proud of you, keep doing what you’re doing love 💗

36 notes

·

View notes

Link

“A pioneering set of “wearable muscles” with a profile similar to a shoulder sling could increase mobility and strength in the arms of people who have lost it.

As algorithmic intelligence advances, more and more engineers are attempting to design different prosthetics to replace lost mobility, but many are large, bulky, complicated, or extremely expensive.

Michael Hagmann has a rare form of muscular dystrophy called Bethlem myopathy, but his muscular output was increased 61% thanks to a kind of exo-tendon called “Myoshirt” which learns the movements Hagmann wants to make before raising and lowering a cable similar to a human tendon in order to apply mechanical advantage to his actions.

“Although hospitals have numerous good therapy devices, they are often very expensive and unwieldy,” said Marie Georgarakis, a former doctoral student at the Swiss Federal Institute for Technology’s Sensory Motor Systems Lab in Zurich.

“And there are few technical aids that patients can use directly in their everyday lives and draw on for assistance in performing exercises at home. We want to close this gap.”

The Myoshirt is a soft, wearable exomuscle for the arms and shoulders; a kind of vest with cuffs for the upper arms accompanied by a small box containing all the technology that is not used directly on the body.

Smart algorithms detect the user’s movements and the assistance remains always in tune with them. The mechanical movements can be tailored to their individual preferences, and the user is always in control and can override the device at any time.

In an alpha-stage test, 12 people including Hagmann and another with a spinal cord injury, performed arm strength tests wearing the Myoshirt. In the 10 who had no mobility issues, Georgarakis et al. found that “onset of muscle fatigue” was delayed by 51 seconds compared to an unsupported arm.

Hagmann experienced a 254 second-delay [over 4 minutes] in the onset of fatigue doing unloaded arm lifts, and the participant with the injured spinal column was able to lift his arms repeatedly for nearly 7-and-a-half minutes more than without the Myoshirt.

At the moment the box containing the motor and computer parts weighs close to 9 pounds, so the team’s first priority is to develop a full prototype with an even more discreet profile to allow people to use it in day to day life as often as possible. [Their other main priority? Taking the exomuscle out of the lab and testing it in real life.]” -via Good News Network, 1/13/23

#disability#muscular dystrophy#ai#artificial intelligence#muscles#spinal injury#mobility issues#science and technology#muscle fatigue#good news#hope#switzerland

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that makes dating difficult when having a severe disability is the lack of privacy. It’s hard trying to remain private when you have to rely on caregivers for EVERYTHING. And many caregivers treat disabled adults like children and can be extremely judgmental especially when the disabled adults are also apart of the LGBT.

#disabled#lesbian#disability#queer and disabled#disabled lesbian#chronic disease#masc#qwoc#dating#wlw community#chronically ill#spoonie#disabled masc#muscular dystrophy#chrinic illness

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disability, Cures, and the Complex Relationship Between Them

So, I've been thinking a lot lately about cures, just in general, as a concept. I've been watching the excellent videos of John Graybill II on Youtube, where he demonstrates his day-to-day movements as someone with Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy 2a, and updates every year to show how it progresses. I'm currently writing a character with LGMD and wanted to be sure I understand exactly how it impacts his daily life and movement limitations, so this has been extremely helpful, because there's only so much you can glean from a list of symptoms.

Quick Background on John Graybill II

John started this series in 2007/8, back when he was about 30 years old. He was diagnosed when he was 17, back in '95, and, when he started this series, he was very much fighting his LGMD, in a constant struggle, and angry with himself and the condition. In this, he directed a lot of toxic positivity at himself and became convinced he could defeat LGMD with positive thinking, healthy diet, etc.

Now, while I respect that there are positives to this (exercise and eating well is rarely a bad thing, and the stretches he does almost certainly have helped him to lengthen his time with mobility), there is also something to be said for accepting a physical disability for what it is. In later videos, he clearly had shifted that mindset toward something a bit more realistic. Where, in the beginning, he had been certain that he would somehow heal himself through positivity and such, he later says that may never happen, and he wants to enjoy doing what he can, while he can, instead of being in a constant battle with himself.

That being said, he does run an organization (I believe he runs it?) that seeks to fund research and find a cure for muscular dystrophy of this particular variety. And, while watching his videos from oldest to newest, I've been grappling with my complicated feelings regarding cures.

Why Are Cures a Complicated Topic?

The reason cures are a complicated topic is because, for a lot of us, cures are unlikely to ever be developed - at least not within our lifetimes and probably not within our children's lifetimes. Many physical disabilities and disorders are just too rare, too unknown, the cause unclear. For us, we have to just accept that this is something we have to live with, for better or for worse.

The other reason is that people are often proponents of seeking cures for things that don't need curing, such as autism. Obviously I haven't polled every autistic person alive, but I have known and read content from countless autistic people. I don't think I've ever found a single autistic person who wanted to be cured of autism. In fact, I would say most of them were pretty vocally oppositional toward the idea, for good reason. 90% of the difficulty that comes with being autistic comes from societal ableism and accessibility issues on a systemic level.

My Thoughts on Cures

I can't speak for everyone with incurable physical disabilities that are unlikely to have a cure developed, nor can I speak for everyone who's autistic, but, speaking for myself, talk of cures can be extremely uncomfortable to me.

I asked myself why. Because, in reality, there shouldn't be anything wrong with researching a cure for something like LGMD. It causes people great difficulty and often great pain. For certain variants, it causes early death.

And, after reflecting on my feelings for a long while, I think I've figured out why the word and the concept bothers me so much.

Cures Are Often Used as a Crutch for Ableism

There are, broadly speaking, two camps of people who want cures:

People who want to improve their quality of life, the quality of life of someone they love, or who want to prevent future generations from the difficulty they or a loved one have been dealt

People who are uncomfortable with disability and want it to go away

This is a venn diagram with a large overlap. The number of people who are purely in camp 1 is much smaller than you might hope.

Why Is Wanting to Get Rid of Disability a Problem?

Okay so here's why camp 2 is a problem. Let's say, for the sake of the argument, that every disability has a possible cure that just has to be found. Why is that a problem? Disability is bad, right?

Wrong! Disability is completely amoral - it has no goodness or badness. It just is. Ideally, some of the more painful disabilities could be cured to prevent pain and early death. However, the problem with viewing disability, in a vacuum, as bad, is that your opinion of the disability will inevitably rub off on the people with the disability.

When you view disability as an adversary, you view disabled people as a problem to solve.

Just as John Graybill II explains in one of his stair-climbing videos a few years into the series, he had spent so long trying to fight the progression of the illness, that he had spent every day in passive anger and frustration. He had forgotten to just enjoy his ability to climb stairs. And he said that he wished he could go back and just enjoy it - stop timing himself on his stopwatch and trying to beat his times. Basically, even as a disabled man himself, he had spent so long looking at his disability as a problem to fix, he hadn't been properly enjoying being a person and just living his life.

When you apply the same fix-it approach to someone who doesn't have a disability, it's equally easy for them to forget the personhood of the people with disabilities. Only, instead of it being directed at themselves, it is directed at others. They push their disabled loved ones to just try harder, just push harder and for longer, eat right, try this, do that, think right, take vitamins - if you just try hard enough, you can beat this!

Except... most of the time, you can't.

The idea that doing everything right will allow you to beat a chronic illness is just ableism in a scientific hat. You're afraid - of being disabled, of the consequences of disability, of someone you love being different, of them looking weird, becoming weird, being seen in public yourself or with someone disabled, of being uncomfortable, of having to put in more energy and effort into helping someone with special needs.

The list of things people are afraid of is endless, and the positive spin on that ableism is simply fighting to fix it.

Make it go away so that you don't have to deal with it anymore.

And then, when you take that approach and apply it to the countless disabilities that don't have cures and may never have cures, you end up with boatloads of people who are seen as problems to solve. They feel like a burden to their family and friends. They're pushed to do what hurts and will actually cause more long-term problems for them by forcing themselves to do things they shouldn't be doing - things that damage their bodies, which aren't meant to do those things anymore.

The Long-Term Consequences of Ableist Pushes for Cures

So back to that argument about all disabilities being curable with time: what's the problem with making some disabled people uncomfortable if, one day, all disability is cured and there are no more disabled people?

Well, the simple answer is this: that's never going to happen, and if you think that way, you're a eugenicist.

Even if every disability is curable with time, the ends do not justify the means - the means being to humiliate and degrade disabled people by treating them like problems.

And it would take decades, maybe even centuries, of those means to even reach the ends. But we'll stop that argument there, because there will never be an end to disability.

Why There Is No End to Disability

So, the thing about disability, is it will never cease to exist. Even if it was a good goal to have, which it isn't, it's never going to happen.

Disability is often caused by gene mutation. At one point, none of the gene mutations for our current physical disabilities existed. They developed. And, just as the current disabilities developed over time and with gene mutations, so will new and different ones. Even if we cured all of the current disabilities, there would always be new ones, likely developing as fast as we can cure the existing ones.

Additionally, a lot of disability is not congenital. People who are in accidents and lose legs will never be able to regrow those legs. Even if eugenicists managed to prevent any "deformed" babies from being born without limbs, people would lose them from accidents and infection, and all kinds of things.

In a world where all congenital disabilities were cured, what quality of life do you expect people in wheelchairs to have?

Because I think I can confidently say that, if everything congenital were cured, a day wouldn't pass before accessibility laws were thrown out the window. We would be returned to the days where disabled people are hidden away and can't leave the house - kept as shameful secrets by families who resent them, or shown off as paragons of strength and virtue when/if they're able to be fitted with a working prosthetic.

Neither of these outcomes is positive.

The Slippery Slope of Cure Ideology

So, on to another argument: there is a lot of danger in letting cure ideology go unchallenged.

I want to clarify again, that I don't think we should never research cures. I'm challenging, specifically, the social movement behind cures that is often driven by eugenicism and ableism.

So, why is it dangerous to let that exist? Well, let's look back at the reason I mentioned that people are in camp 2: they are afraid of being uncomfortable. They are afraid of what's different from them. They view difference as a problem to be solved - a disease or a disorder.

You can see this exact principle in action when people fight for a cure for autism. It's being fought for by the allistics who know people with autism, not usually the autistics themselves. It's being fought for by parents who are angry that their child is different or won't look them in the eyes. They see them as an obstacle to overcome, not as a person who has a different way of socializing. Even in the best case, where they see them as a person more than a problem, they are seen as a person with a wrong and disordered way of socializing.

Imagine, for a moment, that there was an allistic trait that people treated as disordered or wrong the way an ableist might treat hand-flapping or lining up toys. Let's take a direct comparison - something one does when they're happy - like laughing. Imagine, for a moment, that something you do when you're joyful, is treated like a maladaption. Perhaps, in this alternate universe, smiling is normal, but laughing is disturbing to people. You spend your life desperately trying to repress your laughter, hiding your joy, even though it's the most natural thing in the world to you. How would you feel hearing people chanting positively, with smiles, taking donations, running marathons and dancing, all for a cure for laughter?

Really, really, genuinely think about it.

Imagine living your entire life like that.

This doesn't just relate to autism.

The reason this ideology has to be challenged is not just by the concrete example of people trying to cure autism, it's the root of the ideology, that different is bad. That the majority being uncomfortable means the minority is wrong and needs to be fixed.

Is this ringing any other bells for you? Because autism isn't the only thing I desperately hope they don't find a genetic link for.

If fighting for a cure for anything people deem different and weird enough goes unchallenged, people will attempt to cure anything they don't like. Like being gay. Or being trans.

And I'm not talking about conversion camps that try to brainwash you into thinking you're not gay. I'm not talking about the abusive Christian approach, I'm talking about the eugenicist scientist approach.

If a genetic link were found or if there was some kind of actual biological difference, that could mean people trying to test fetuses for the "homosexuality gene" or whatever. It would give a concrete path for eugenicists to try preventing gay and trans people from ever even being born.

And, if that biological connection is found, how long do you think it would take for people to start excitedly pushing for a cure to "homosexuality" or "transgenderism"?

What is the point of this post?

It's food for thought.

I want, not only my abled followers, but my disabled ones as well, to reflect on how they feel about cures - about being cured or about curing others.

I want you all to ask yourself, am I in camp 1 or camp 2?

Your goal in supporting a cure should be to prevent death, to prevent pain that cannot be overcome through systemic support and accessibility, to help people live lives with quality.

Your goal in supporting a cure should never be to remove something that makes you uncomfortable. If you're abled, it should never be to make your life easier or alleviate your feelings of guilt, resentment, or stress. It should never be to make people normal, especially not people you care about.

And, on a final note, remember that the things you see in a disability you know nothing about may not have anything to do with reality. If you see a disability for the first time and you immediately wish for a cure for it, simply because it looks painful, maybe find out if it actually is first. Sometimes we attribute pain and misery to things that are no big deal to the people dealing with them. And, in doing so, we also attribute heroicism and virtue to the people dealing with them - which they did not ask for.

Don't make disabled people into a project. Don't use them as inspiration porn - putting them on a pedestal and using them as proof that "anything is possible."

Treat disabled people with dignity and respect.

Treat disabled people as people, with or without them jumping through every hoop you think will make them better.

Think about how fucking annoying it would be if, every time you got up from a chair in public, everyone stared at you, or even praised you for it. How uncomfortable would you be if no one ever saw you as yourself but as some kind of ambassador for strong, amazing people who are so so so cool because they can tie their shoelaces.

Think about how fucking infuriating it would be if every tenth person you walked past turned to you, looking sad, and said "god bless you."

Think about how old that would get, and how fast.

That's all. Just think about it.

#there are like 6 different points in this post fighting for dominance#i hope you walk away with all 6#disability#ableism#ableism mention#chronic illness#actually disabled#disabled#lgmd#muscular dystrophy#autism#asd#autistic ableism#adriandontlook#queer#lgbt#long#long post#longpost#pots#eds#fibro#fibromyalgia#postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome#ehlers danlos syndrome

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still have trust issues with abled body people. But the only ones I don’t have trust issues with is my partner and my close friends.

I don’t care if you unfollow cuz of that as well. I should be allowed to show my frustration with most able body people

I shouldn’t ask nicely for you to put a ramp down. If you can walk on stairs without asking politely, I should be rolling on ramps without asking nicely

Like if I’m coming over to your house, you should be putting a ramp on your stairs before hand. Not just expect me to be like “pretty please, let me go up your steps 🥺”

Like again, I don’t see you asking for freakin’ stairs.

#cripple punk#cripplepunk#angry cripple#disabilties#merosin muscular dystrophy#muscular dystrophy#disabled#physically disabled#ableists dni#please don't comment on or derail this post if you're able bodied

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

you fundraised over $2,000 for muscular dystrophy research! you don’t know how much that means to me as someone with muscular dystrophy! I wanted to ask, how did you do it? I’d love to fundraise in my own community. Any tips on how to start?

Thank you so much!

I am a member of a fundraising team for my local chapter of the FSHD Society for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, the type of MD that I have. As far as I know, the FSHD Society only operates in the USA and Canada, but they have a list of some global FSHD groups here.

The FSHD Society does an annual fundraising event called the Walk and Roll to cure FSHD: this is the only major fundraiser specifically for FSHD in North America. This is the primary way that I've raised money in the past.

Anyone can participate, but the best way is to join or create a fundraising team (fundraising teams raise more than 80% of total donations). FSHD is genetic, so the team I'm on consists mostly of my family members and a few friends that also have FSHD, which classes us as a Friends & Family team (as opposed to a corporate team). You need 4 or more people to make a team.

Teams create a website or Facebook group to document their goals and progress. I'm not sure whether or not this is required, but definitely creates a much easier way for people to send in donations online rather than with cash/check.

Then, get the word out! The easiest way to do this is with social media posts that link to your team's webpage, but some teams also put out flyers. And depending on where you work, you could ask your business to be a corporate sponsor, or do a corporate match program, where every dollar donated by an employee is matched by the corporation. Depending on how much you raise you can receive branded items in return: I've gotten an umbrella, backpack, and duffel bag.

If there is no Walk and Roll event near you, you can participate virtually or donate to the FSHD Society at any time through their website.

My team's $2,000 worth of funds raised is actually on the lower end compared to most other teams, who average over $3,000! But remember that every cent counts towards finding a cure for FSHD and helping people living with it :)

#unfortunately i will not link to my teams webpage#because it contains my full name email and phone number#i love you guys but that's a little too personal to share on here#muscular dystrophy#FSHD#fshmd#facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I recently learned that "normal" people don't experience constant physical pain?

I can't think of a single second when I've been completely at peace.

Like I put myself through so much pain on the daily, just to do the things I love

#disabled#disability#actually disabled#cripple punk#cpunk#chronic illness#chronically ill#pain#selenon#muscular dystrophy#congenital muscular dystrophy#cmd

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

where are my toe walkers at. high gaits, related to neurodivergence or related to a physical medical condition it doesnt matter, weird walkers UNITE

#i don’t do it because of autism but i will use autism tags cuz y’all often do (but for different reasons)#autism#autistic#actuallyautistic#but i do it because of muscular dystrophy stuff so here are more tags#chronic illness#actually chronically ill#disability#actuallydisabled#muscular dystrophy#charcot marie tooth#i can only wear shoes with heels or wedges it sucks but tis life#luckily i like goth platform boots#cmt#personal

102 notes

·

View notes