#or John or something unconventional and masculine

Text

thinking about it as i re-read the original sins volume, and i know i say constantine enjoys pissing people off, but really it's more like? not letting people get away with the small shit? the snide side-comments, the sideways looks, the baldfaced assumptions, the microaggressions — he likes to rub people's nose in their own shit, make them face it, own it, try to defend it. which, as an openly queer, working class, actively anti-racist man in the 80s, does end up causing a lot of fights.

#( ooc. ) OUT OF CIGS.#he still loves pissing people off but the part that mostly Does piss people off is the confrontation. the lack of patience for bullshit#like something i forget a lot about the comics until i come up against it is the amount of homophobia john faces??#i never really think of him as being super visibly queer but he gets called slurs Quite a few fucking times#and part of that is that he's unconventional & an old punk rocker & a dandy & stopped performing toxic masculinity a loooong time ago#but he also just. does not seem afraid of being Perceived. and when he is he doubles down and owns it#like that panel in i think 'books of magic' where someone tells him gin & tonic is a queer's drink & he goes 'pay u $25 to suck my dick ;)'#his magic is all about misdirection but he's only so good at it bc at heart he is a person who will always look you dead in the eye#all your internalized garbage and nasty assumptions? he sees it. he meets it head-on. he might care but he won't seem like it#he's too old to internalize that kind of nonsense. fix your hearts cowards#this is also why he's such a good manipulator: you're the one making it clear what you want. he just has to pretend to give it#anyway. i love him your honor#( headcanons. ) I'M JUST LIKE THE BASTARDS I'VE HATED ALL ME LIFE.#homophobia cw#just in case

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Lennon and Yoko Ono--The Astrology of The Beatles Part Three

This has become somewhat of a series. Read part one with Paul and Linda's synastry. Part two: the Synastry of John Lennon and Paul McCartney

In part three, we’re discussing the synastry of John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Interestingly enough, they have the same meeting destiny points as Linda and Paul's synastry. John’s North Node conjunct Yoko’s ascendant and his vertex was conjunct her ascendant. I always look to Nodes and Vertex as a fated meeting. Especially when the North Node (Our soul mission) is in hard aspect to another person's birth chart. This could mean this person can speed up what a soul wishes to learn this lifetime.

I explained John’s 'soul' theme in the last post. He had a North Node in Libra in the 6th house (of service, health, routine).

John's south node (our past lives and always the opposite of the North node) was in Aries, conjunct his Lilith in the 12th house. His past life shows wounding with women and his sexuality. I would say in a past life, he could have been very self-serving and independent, perhaps of masculine energy, of war, order, logic, and discipline. This might have influenced his lesson in this life with women. Back then, John didn't need others or wanted to be a part of others, particularly women.

Other feminine wounding aspects are the moon-Chiron aspect and moon-Pluto in his chart. I wonder what his relationship was like with his mother before she passed. Or the relationship with his first wife? There's a rage that lies here. This masculine vs feminine energy was going on inside of John and played out in his relationships. He had to learn how to be less self-serving and try to accomplish a life that surrounded feminine divinity, fairness, partnership, peace, collective, sex, pleasure, and creation. Things that remind me of Libra..

Libra suns learn of themselves through another person. With his sun and north node in libra, intimacy is something that could heal and break him. Intimacy would help him grow if he was conscious of the need for partnership. If he wasn’t conscious of his need for partnership and went back to his previous life of intimacy, it would show through prisons, addictions, violence, karma, and enemies, the dark side of the 12th house.

So what does this have to do with Yoko? The 6th house is his theme in libra and Yoko’s ascendant is in Libra and conjunct John's Sun, Mars, Node, & Vertex. He saw in her what he longed to express. Libra rising’s display of charm and art, beauty, care, and the themes of Venus that John knew was something he wanted to accomplish this time around. A part of his sexuality that he ignored before.

There was emotional healing Yoko provided with John. Yoko inspired and awakened what he needed or wanted to live, her Lilith sextile his Chiron, and moon offered John an unconventional way to heal his inner wounding with feminine energy.

Thier other parts of the synastry

John's Venus in Virgo Conjunct Yoko's Neptune: They shared a love for service, and routine, and what Yoko (Neptune) offered John seemed like a sort of spirituality, privacy, and intimacy, the Neptune can represent that they idealized the ideal of servicing humanity together and expressing such a thing through their art.

Let's point to the composite with the Sun, Moon, and Mercury in the 12th house, this can represent an affair between two people, it can represent seeing each other's flaws, dreams, spirit, and drowning deep in a love where it's hard to see anyone else.

Their relationship was complicated, and it's written in the stars, the theme of air signs with Libra and Aquarius on both sides. Created a meeting of the minds. The 6th house theme creates an easiness to rely on each other, and the love of everyday life together. The 12th house shows an element of what goes on between us no one could ever understand. Let's shut the world and our loved one's out and focus on each other. Or since their ascendant was conjunct their personal planets in the composite, their inner world was put on display.

Because of the air theme between John and Yoko's chart, I can see how this can create some kind of coldness for those outside of their relationship, kids, exes, parents, and friends. The focus was on each other, and when it was time to look outside of each other, it was easier to look at the ideal of the collective rather than those around them.

Their peace in bed campaign makes sense. They gave the world a display of their own intimacy, as their composite chart has ascendant conjunct their moon and mercury. Let's make what we share a display for the good of human beings, a great message, but can be a way to block facing their issues with those closest to them head-on.

But, it was part of John's soul mission to understand the collective, fairness, imagining a world of peace, a vision Yoko made him believe was possible. Through Yoko, he could fall in love with the light side of Venus. Learning and basking in this, the leisure and pleasure that Libra is all about, gave John the permission to love and be responsible and want to serve others. How he serviced others was showing what Venus could be about for humanity.

#beatles astrology#paul mccartney#john lennon#yoko and john#john lennon and yoko uno#synastry#libra#virgo#aquarius#compisite#12th house#ascendant conjunct north node#north node#6th house#astrology#celebrity strology#love of astrology#music#movies#celeb astrology#celebrity astrolo#celebrity astrology#libra ascendant#paquarius sun#libra sun#yoko ono#john lennon and yoko ono

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Christopher Nolan remains one of the most significant filmmakers of the 21st century. The mere fact that stating this aloud invites a bit of controversy underlines how outsized a footprint the writer-director has left during the first 25 years of his career. Celebrated by some as a formative auteur in the lives of young cineastes, and derided by others as the patron saint of “film bros” who devour hyper-masculine Hollywood spectacle (particularly if it features capes), Nolan’s already built a formidable and debated legacy.

But in the summer of 2023, his impact was crystalized again when Nolan convinced one of the ever increasingly risk-averse Hollywood studios to invest more than $100 million into an R-rated, three-hour, and existentially despairing biopic, and then released it at the height of summer. That the movie opened bigger than most of the year’s alleged blockbusters, and bigger than any Nolan film not starring Batman, is a testament to the mystique this singular storyteller has cultivated with audiences. Only a handful of other directors have developed such a wide following by melding artistic intent with shrewd commercial sensibilities.

But if Oppenheimer is something of a culmination for the last quarter-century of output from the filmmaker, does that mean it’s his best? And where do the other 11 films he’s helmed rank? We have some ideas….

12. Following (1998)

Christopher Nolan’s first film was a production the young talent shot with his wife and producer, Emma Thomas, and their friends on weekends. No one wanted it to conflict with their day jobs. It’s a testament, then, to Nolan’s earliest craft that you could never tell this by watching Following. However, you can definitely recognize this is a first film from a talented if still rough around the edges filmmaker.

Released when Nolan was only 28, the movie is in many ways an experiment in themes and ideas that would color the rest of the writer-director’s filmography. Like most of Nolan’s early output, it’s a neo-noir picture about the self-destructive obsession of a flawed protagonist, who in this case cannot help but pursue his desire to follow strangers home. In a narrative unspooled via nonlinear storytelling, and shot on black-and-white 16mm film stock, we are invited to likewise follow a nameless and unemployed young man (Jeremy Theobald) as he walks behind strangers for fun. The lad’s vaguely Hitchcockian voyeurism becomes his undoing, though, after he is spotted spying on the criminal underworld. Viewed today, it’s not entirely polished, and the narrative strands more knot and jumble than weave and coalesce. Still, the compelling hook of Nolan’s penchant for unconventional structure and unreliable narrators was already in place.

11. Tenet (2020)

Contentiously released during the fall of 2020 at Nolan’s insistence, Tenet positioned itself as a savior of movie houses during the pandemic. This was, in retrospect, a tall order for what is Nolan’s most ambitious action movie, as well as his most remote and exasperatingly opaque. Reappraisals have already begun, with some arguing Tenet was the director attempting to see how far he could lead audiences down the path of esoteric “vibes”—there is the famous line “don’t try to understand it, feel it”—but we’d contend Tenet remains a bridge too far.

With the conventions of modern action cinema intentionally sketched at their thinnest and most utilitarian (John David Washington’s character is simply called “The Protagonist”), Tenet nonetheless presents a dizzyingly complex world and challenging sci-fi idea in which the entropy of objects and even people can be inverted—allowing most things to travel backward in time. Yet the execution is so needlessly obtuse, and the sound design intentionally confounding, that it doesn’t matter if you understand it; the main thing you’re feeling is frustration and annoyance. There are some dazzling action set pieces, and Hoyte van Hoytema’s cinematography and Ludwig Göransson’s score are sumptuous, but even after figuring out just how many Robert Pattinsons are running around at various stages of inversion, the movie remains little more than a stylish puzzle box that’s far too pleased with its configuration.

10. Insomnia (2002)

Very few directors on this side of the millennium have gotten Al Pacino to deliver a restrained and sharp performance that understands some lines can actually be underplayed to marvelous effect. Christopher Nolan is one of them thanks to his icy remake of a Norwegian film of the same name. Another excursion into neo-noir, Insomnia follows in the footsteps of many post-Se7en and Silence of the Lambs Hollywood murder procedurals, casting one movie star as the cop (Pacino) and the other as the killer (Robin Williams).

The cold-blooded cunning of Insomnia comes from the revelation that the killer is no genius, but rather a somewhat pathetic loner with a reptilian brain who, through a grim twist of luck, is able to blackmail his pursuer into becoming his accomplice. In hindsight, the film’s fascination with the duality between hero and villain was a warm-up act for The Dark Knight, but the restrained Insomnia is often more unsettling due to how calmly both actors are asked to essay their characters, with Williams making for an exceptionally soft-spoken demon, and Pacino for a compelling corrupt cop circling the drain. If the film was allowed to better breakaway from the conventions of these types of early 2000s movies, it might’ve been an actual classic instead of an absorbing, if less memorable, star vehicle from an era when studios would let stars appear in such fare.

9. Batman Begins (2005)

The placement of the Batman films on this list will undoubtedly be the most contentious thing for readers, but please understand we all think Batman Begins is a great piece of entertainment, as well as the finest superhero origin story ever produced. Told with what was at the time a shocking amount of gravitas and charm, Batman Begins recognized superhero movies as material worthy of serious cinematic consideration. Such a feat arguably had not been seen since Superman: The Movie (1978). Yet therein lies Batman Begins’ limitations.

While Nolan’s first Batman film is still the best version of any caped origin story, Batman Begins follows to a tee the formula as set down by Dick Donner in ’78. That does not take away from how confidently well-formed this film is, as well as how it offers the still best cinematic interpretation of Bruce Wayne, who is given a poignant dignity in Christian Bale’s sad eyes. Together, the director and star perform their own kind of stage illusion, convincing audiences to take a man dressed up as a Bat seriously. Somehow you buy into the idea that he is a major city’s best hope at an urban renewal. It’s an intriguing idea to turn the Caped Crusader into something of a theatrical political campaign—one whose surrogates include a murderer’s row of acting talent like Michael Caine, Gary Oldman, and Morgan Freeman. It’s also the beginning of a fruitful relationship between Nolan and Caine, the latter of whom appeared in all but one of Nolan’s following nine movies. However, many of those others were better, not least because their third acts did not descend into stock genre trappings.

8. The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

Yes, a case can be made for The Dark Knight Rises being Nolan’s second best Batman film. Often overshadowed by its direct and far superior predecessor, The Dark Knight, Rises is usually written off as the ugly duckling of the trilogy. That’s ridiculous. Told with a sweeping grandeur intentionally evocative of David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago, and prescient in its fear of a demagogue’s ability to turn an American crowd into an angry mob unleashed on the halls of power, this is the type of epic, cinematic storytelling we rarely see anymore. And it looks nothing like any other superhero movie that’s been made before or since.

Beyond its scope remains a film that also raises a still subversive and controversial question in this genre. What if the hero lets go of his pain, and learns to put away the simplistic morality of a mask? Christian Bale gives his best performance as a wounded and broken Bruce Wayne who needs to grow up before he grows old, and also before he is pulverized by one of the most memorable screen villains of the last decade, Tom Hardy’s infinitely quotable Bane. (It’s also genuinely impressive Nolan confidently keeps the Batman costume off-screen for over an hour.) Throw in Anne Hathaway’s slinkiest performance as an underrated Catwoman, as well as some stunning action sequences, and you’re left with the rare thing: a satisfying ending to a superhero story.

7. Dunkirk (2017)

Despite crossing over into the relatively well worn genre of war films, Dunkirk proved to be Nolan’s most experimental project to date. Told with a clockmaker’s precision and blocked with what might be the director’s most painterly compositions, Dunkirk foregoes anything in the way of modern cinematic storytelling, particularly at Hollywood studios, in favor of a stripped down and overtly challenging narrative structure. There are no character names (at least any you’ll remember), scenes of audience-aiding exposition (one of the weaker elements in Nolan’s scripts), or nearly any dialogue at all for that matter.

Instead Nolan relies on a visceral film language to convey all the important information through imagery. If not for its bombastic sound design and Hans Zimmer’s propulsive score, Dunkirk could be a silent movie, albeit a unique one since it’s told on three parallel timelines that converge during the darkest hour of Britain’s war effort in WWII: getting 338,000 soldiers off French shores before the Nazis close in. No other film has quite immersed audiences into the overpowering desperation to survive during war, nor has Nolan ever surpassed the visual poetry of Hardy standing before the burning wreckage of his plane at twilight on a beach, personifying British resolve while caught in the seeming jaws of defeat.

6. The Prestige (2006)

In what might qualify as their first self-reflective film, Chris and his brother Jonathan Nolan liberally adapt Christopher Priest’s The Prestige into a treatise on the sacrifices an artist will undergo in order to master their craft—perfecting the ability to ensnare and enrapture an audience. But like the book, it’s channeled through the enigmatic spectacle of two Victorian illusionists descending into a lifelong rivalry that turns fatal.

As these selfish magicians, Bale and Hugh Jackman do some of their most under-appreciated work, each representing one of the key sides of talent: the artist who wants to be the best in their field, and the showman who wants to be adored by the crowd. Technically, this movie is a period piece, but its urgency and zeal feels timeless. Still, the character it might most sympathize with is a definite relic of its setting, Nicola Tesla, who after watching the film now seems to have always been destined to be played by David Bowie. Tesla was a genius in his time, yet was overshadowed by the capitalistic cunning of men like Thomas Edison. Back then, Edison was called “the Wizard of Menlo Park” (inspiring another Oz-ian figure in fiction), but as realized here, Tesla was the true magician; a man who applied practical science and technology to problems until he created, as one character shudders, “real magic.”

5. Interstellar (2014)

Nolan has never been a director to hide his influences. In fact, he often wears them on his sleeve, such as when Interstellar overtly announces it will try to go beyond the monumental benchmark set by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. If that movie’s journey ends among the moons of Jupiter, then Interstellar’s galaxy-brained odyssey begins in a wormhole just off Saturn! That’s chutzpah for you. But while Interstellar is no 2001, it is still one of the best sci-fi movies of the past 20 years and almost certainly better than you remember.

Despite the director being rightly criticized for a frequently chilly and cerebral disposition in his films, Interstellar is an aching exception to that rule, with Nolan not-so-subtly grappling with feelings of guilt and regret over leaving his kids at home for extended periods of time. For Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) and his young daughter Murph (Mackenzie Foy), this is taken to a cosmic extreme because, in order to save the human species from climate change, Coop and several other scientists travel to another galaxy where time dilation makes decades pass on Earth in the span of a day on the ship.

In terms of scope, it’s Nolan’s biggest film, and yet it is also his most intimate and sentimental—which doesn’t mean it isn’t chilling due to the horror of a parent seeing Foy age into Jessica Chastain in the blink of an eye. The movie’s also fairly wondrous, with the filmmaker and Nobel Prize-winning physicist Kip Thorne correctly hypothesizing what a black hole would look like before the real thing was photographed several years later. This is a sweeping epic that haunts, and this is in large part due to Hans Zimmer’s ecclesiastical, organ-driven score. Zimmer may not have won the Oscar that year, but it’s telling the Academy used Interstellar music for their own 90-year retrospective a few years later.

4. Memento (2000)

The lone independent film with a serious budget in the director’s oeuvre, Memento remains the cool kid answer to the question of what is the best Nolan film. And sure enough, to this day it’s a defining calling card. As the infamous neo-noir thriller “told backwards,” Memento is a marvelous magic trick where Nolan, working from a shorty story by his brother Jonathan, perfected his nonlinear filmmaking with a puzzle box that intrigues and engrosses on every rewatch.

In the film, we meet Leonard (Guy Pearce). Leonard has short-term memory loss, which means he knows no better than the audience why he’s left a note to himself to execute Teddy (Joe Pantoliano) on a crappy concrete floor. Yet as the narrative unspools mostly in reverse, we learn a great deal about Leonard’s disorienting condition, and slowly how he had a hand in crafting his own hell. In some respects, Memento is a stylish showpiece meant mostly to impress and flabbergast the audience through its narrative cleverness. That isn’t a bad thing though when the movie is this stylish and clever. Ironically, it even becomes pretty unforgettable.

3. Inception (2010)

The other sci-fi movie that’s really about moviemaking on the list, Inception has probably entered the status of a classic at this point with its now iconic narrative about chic thieves infiltrating the dreams of wealthy marks. The parallels between the team assembled by Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and the heads of various filmmaking departments are well-known these days, but beyond the film’s meta and intertextual qualities is just a dazzling triumph in imagination and spectacle.

Cobb and his team dress like the most refined members of a James Bond ensemble, yet the actual posh worlds they move through are enticingly knotty, slowly unfurling their complexities like the M.C. Escher stairs the film pointedly duplicates. Stacking dreams atop dreams, and expanding time compressions on each layer, Inception invites audiences to get lost in its labyrinth, even as it wisely never lets go of the audience’s hand while acting as our guide. This paradox of being both convoluted and surprisingly simple may be the secret of Nolan’s appeal, and those two sensibilities are rarely in better harmony than in the one with visions of a rotating hotel hallway and the skyline of Paris folding in on top of itself as Hans Zimmer’s deconstruction of “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” blares.

For some, this is the definitive Nolan film. And that case can definitely be made, yet the film is such a mind game—and the emotional crux between Cobb and his underwritten wife Mal (Marion Cotillard) is such a frosty center—that there are a few more we give the edge to.

2. Oppenheimer (2023)

In many respects, Oppenheimer seems to be the movie Nolan’s entire career has been building toward. Interspersed nonlinear timelines, dreamers attempting to make the visions a reality, and tales about obsessive individuals pursuing an idea until it destroys them are all realized in IMAX photography by Hoyte van Hoytema that is as intimate as it is overpowering. But by removing Nolan’s usual genre and action set-piece flourishes, and instead centering these larger fixations on the tragic story of J. Robert Oppenheimer and his creation of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer makes Nolan’s muses more visceral and despairing than they’ve ever been before.

The terms “magic trick” and “illusion” come up a lot when discussing Nolan’s filmography, but the horror of Oppenheimer’s work is there is nothing illusory about what he created; it changed the world by (maybe) saving it from a lot more carnage in WWII but it also did so by committing a war atrocity that put us on a path to seemingly inevitable self-annihilation. Oppenheimer realizes this in his head, and the film likewise does so with Nolan blending multiple timelines in the editing like a composer utilizes an orchestra. The effect is an incredibly suspenseful panic attack that never lets go of your nerves in spite of a three-hour running time and settings rarely more grand than men sitting at a table. The ensemble is phenomenal even if (once again) the women don’t get enough to do. Nonetheless, Nolan’s frequent collaborator Cillian Murphy turns in the performance of a lifetime as Oppie, and it’s in service of a film that increasingly appears to be a masterpiece.

1. The Dark Knight (2008)

It’s almost a cliché these days to place The Dark Knight at the top of any list it appears on, and yet the gloomy draw of the superhero film is as irresistible now as it was 15 years ago. Exceeding anything its genre has produced before or after its release, The Dark Knight is a transcendent feat in American moviemaking and one of the finest films produced by the modern studio system.

Ironically, it’s also a film that stands apart for Nolan as well. To date, it’s the only movie on this list told entirely in a chronological order, and one that seems less concerned with the effects of time on an individual as it is with the weight of the future on a greater collective. Indeed, Gotham City has never more convincingly felt like a real place than in this ensemble film about how American institutions crack under pressure (particularly due to the threat of terrorism in the post-9/11 years). Gary Oldman’s copper Jim Gordon and Aaron Eckhart’s district attorney Harvey Dent are as much protagonists as Bale’s tortured vigilante. And how they all react to the existential threat of Heath Ledger’s Joker is exhilarating on each viewing.

Ledger deserved his posthumous Oscar as chaos and nihilism made flesh. He turned a comic book character into one of the greatest portraits of ill-intent in cinema, but everything about this film is firing on all cylinders, from Nolan and cinematographer Wally Pfister pioneering IMAX photography in narrative filmmaking to Michael Caine’s perfectly measured monologue about the nature of evil and societal collapse. This is a movie decidedly of its moment, yet also an achievement that will stand for all time.'

#Christopher Nolan#Oppenheimer#Tenet#Dunkirk#Interstellar#Inception#Insomnia#Following#Memento#The Prestige#The Dark Knight#The Dark Knight Rises#Batman Begins#Heath Ledger#The Joker#Christian Bale#Robin Williams#Guy Pearce#Robert Pattinson#John David Washington#Jeremy Theobald#Emma Thomas#Ludwig Goransson#Hoyte van Hoytema#Al Pacino#Superman: The Movie#Michael Caine#Gary Oldman#Morgan Freeman#Tom Hardy

0 notes

Photo

THAT MOMENT, BREAKING—Apprenticeship to Love: Daily Meditation, Inspirations, and Practices for the Sacred Masculine, October 31 • For the full meditation, practice, & more from tomorrow’s #apprenticeshiptolove chapter please subscribe on Substack or email me at [email protected] and be one of the free “first 1000 early readers.” • Two of tomorrow’s Inspirations… “The moment you think: “Yess, I’m in balance!”, something unexpected happens and… you are out of balance again, hèhè! It happens so often, that it seems to be part of life. It actually shows us that being out of balance is okay! The question is: How are you dealing with ideas, diagnoses, interpretations, judgements that say that you are out of balance?…” (Tim & Marieke, Kundalini Yoga School, Creativity sadhana) “The second obstacle I see men face [in their disconnect between desire and ability] is a real connection to feeling —not just emotion, but the ability to sense their own bodies and environments.” (John Wineland, From the Core) ✨ ✨ ✨ #pathofthesacredmasculine #husbandman #authenticrelationships #love #nervoussystem #devotion #surrender #choosevulnerability #siren #sirensong #nervoussystemtraining #patience #masculine #menshealth #marriage #unconventional #relationships #trust #confidence #safety #awareness #herosjourney #sacredmasculine #menswork #SACREDSEX #presence (at Courtenay, British Columbia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkWPGalPKqG/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#apprenticeshiptolove#pathofthesacredmasculine#husbandman#authenticrelationships#love#nervoussystem#devotion#surrender#choosevulnerability#siren#sirensong#nervoussystemtraining#patience#masculine#menshealth#marriage#unconventional#relationships#trust#confidence#safety#awareness#herosjourney#sacredmasculine#menswork#sacredsex#presence

0 notes

Text

Character design of a spooky skeleton! 🧡💀🎃

#character design#skeleton art#spooky#Halloween#my art#my oc’s#I have only heart eyes for her 🥺💕#what do you think I should name her? cause I was thinking maybe Joel#or John or something unconventional and masculine

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

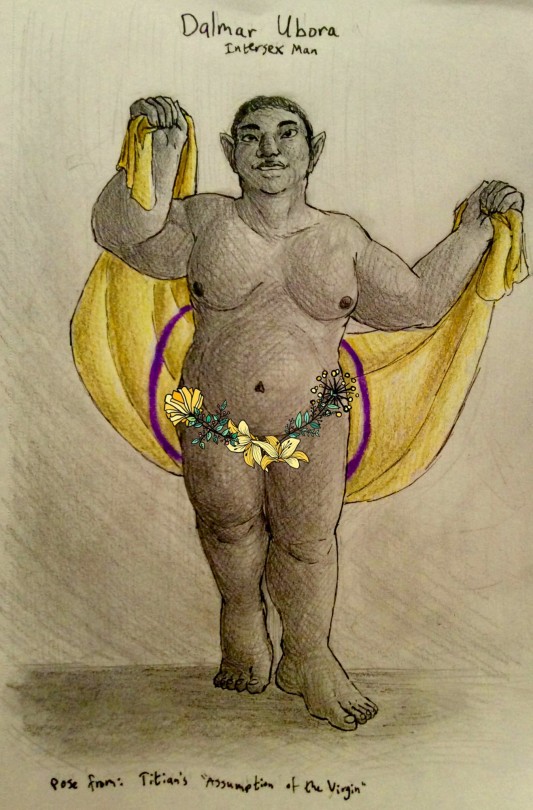

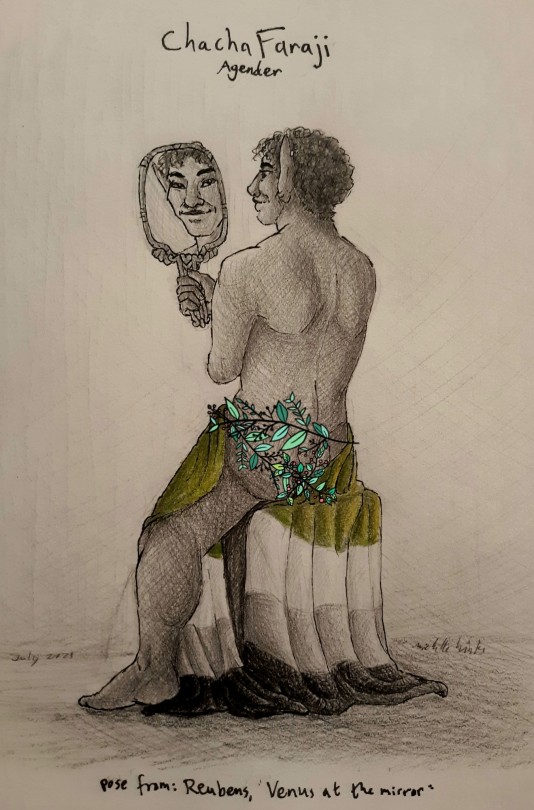

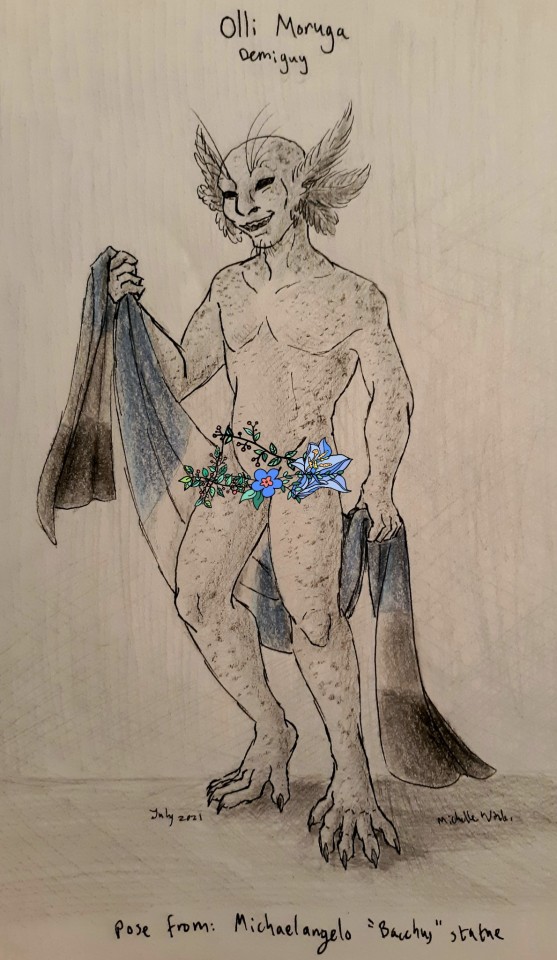

(image description: eight sketchbook drawings of characters holding a variety of pride flags, all nude and posed in ways that match some old fine art pieces. The nudity has been censored with cute digital flower stickers. end description.)

Characters:

Dalmar, intersex man. Kouto, nonbinary. Chacha, agender. Parva, nonbinary. Xulic and Kidron, genderqueer. Obeli (or Abuela) Moruga, genderqeer. Olli, demiguy. Sajak, genderqueer.

Genderqueer is kind of my default for "well, biologically and culturally, they already don't have binary sex or gender, so they kinda default to genderqueer." And I know maybe some people will be bothered by that, but it's just part of the worldbuilding I've written around all these non-human and frequently non-mammalian species of people.

The uncensored version is on my Patreon page. I do have one more drawing to add to this series, but since it's four child characters I will not need to worry about adding any censors and keeping the original image only on my patreon, as they will simply be wearing their pride flags as whole outfits.

The previous part of this, my binary trans characters, can be found over here.

detailed character descriptions and explanations of the pose references under the cut

Dalmar Ubora, a black intersex elf man with short black hair. He is holding his arms up as he holds the intersex flag, mimicking the pose of Virgin Mary from Titian's painting "The Assumption of the Virgin". The shading was washed out by the photo, but his belly is still clearly round from pregnancy. Dalmar is an interesting case, in that he was assigned male at birth based on his outward appearance, continues to identify as male throughout his life, but finds during puberty that what was believed to be an undeveloped penis was actually just a non functional body part. Instead, what actually developed to full functionality was his uterus. He still identifies as a straight cis man, and has come to terms with his body. He is married to a medically transitioned trans woman, and he could undergo operations to change his body if he wanted to. Instead, he has embraced his body and even birthed some children who were conceived via sperm donations. This is why I wanted a Mary pose for him, and this painting in particular is about Mary being welcomed into heaven as a blessed holy woman. Dalmar may not be a miraculous holy figure, but there is a reverence in the way he has come to love his body and chosen to bear children, including the surrogate birth of his brother's child.

Kouto Hayashi-Loryck, a slender nonbinary elf with black hair tied into a bun. They are holding the nonbinary flag and standing in the pose of a statue known as "Apollo Belvedere", which is so old no one knows the artist's name. One arm raised, one lowered, legs in the relaxed contrapposto pose. Kouto is an artist and an art model. Apollo is a god of the arts, and regarded as a beautiful and sexual figure. Kouto is bisexual and admittedly a very sexual and flirtatious person. They did settle into a happy marriage though (actually they are Dalmar's in-law and the sperm donor for the aforementioned surrogate birth.) Marriage has not stopped Kouto's flirtations, merely limited their targets to a singular person. It felt right to give him this pose, from a pretty well known portrayal of Apollo. Beauty, art, and sex, all defining traits of Apollo and Kouto alike, all present in a pose where the figure seems to be reaching for something above them.

Chacha Faraji, an agender black elf with short hair. They are facing away from the viewer, seated on a stool that is covered by the draped agender flag. No physical traits that could betray their agab are visible. Chacha is sitting in the pose of Reubens' painting "Venus at the Mirror". The arm closest to the viewer ends at the elbow, while they hold a mirror in front of their face with their one whole arm. Their face is seen reflected, smiling, little wrinkles visible by their eyes. I chose this painting in part because it did allow me to obscure Chacha's agab. They were my first nonbinary character, and I never really settled on an agab. But also, I enjoy putting characters who have unconventional bodies into poses associated with Venus or Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty. Chacha is missing half an arm, they are getting older and it shows in the wrinkles on their face. Chacha is also Aromantic and Asexual, the full queer triple A battery. The mirror pose has become an independence of beauty. "Look but don't touch." Chacha is beautiful, and they do not need to be beautiful for anyone but themself.

Parva Turbatus, a white nonbinary elf with shoulder length curly hair that has been shaved down on the far side of their head. They are holding the nonbinary flag, standing in the slightly closed off pose found in Paul Gariot's painting "Pandora's Box". One hand on their chest, one hand held out to hold the flag. They have top surgery scars on their chest and a c-section scar on their navel, though all of these have unfortunately been hidden by the flower censors. I chose a pandora pose for Parva because they have one of the most intense tragic backstories of any of my characters. Like Pandora opening the box, they have suffered through many things but came out the other side with Hope, and healing.

Xulic Vos and Kidron Engedi, a drow and a lizard person. They are sharing the genderqueer flag. Xulic has long ears and white hair in a braid, with a white monkey-like tail barely visible behind their legs. Kidron looks like a leopard gecko, and their tail is acting as a visual block in fron of Xulic's groin. They are standing together in the central pose of Raphael's "School of Athens" fresco. Xulic is pointing one hand up to the sky, while Kidron holds one hand palm down towards the earth. Xulic's chest is visibly flat, however I have rewritten the drow as a eusocial people, who's biology has made most of the common population infertile and visibly near identical above the waist. Xulic's agab is unknown to anyone but them, and perhaps their reptilian lover Kidron. Both drow and lizard folk have biology and cultures that do not really support a gender binary, so genderqueer suits them both quite well. I chose the School of Athens pose because these characters are scientists in fields that overlap, and they often get into deep discussions on the matter. Xulic is a paleontologist while Kidron is a geologist, and they have another friend (my protagonist) who studies archaeology.

Obeli (or Abuela) Moruga, an elderly goblin with sagging skin and axolotl-like frills on the sides of her head. She grins as she holds the gender queer flag, partly draped over the tall stool she is seated on. Her pose matches that of John Collier's "Priestess of Delphi" painting, which depicts a woman hunched over herself on a stool. Old Obeli Moruga, whose title best translates to "grandmother" is a significant figure in her community, both because of her more practical role as a leader and wise woman, but also because she has gained immortality and become an incarnation of Life Itself, after she was given the offer of such power when she nearly died in the goblin revolution. There are many figures that would suit her. Poses from statues of goddesses, like Athena or Gaia. Perhaps turning away from the theme of greek and roman figures I ended up with for my nonbinary group (dalmar is his own thing) and using the famous painting of Liberty on a battlefield. But now in her old age, all those poses of figures in more active poses, tall and imposing, simply didn't feel right. A wise old woman, hunched on a stool in a pose associated with the idea of an oracle, a priestess, a prophetess, felt much more fitting. (goblin culture does have specific pronouns for leadership, and in the common speech they have decided this translates best to the feminine "she/her")

Olli Moruga, also a goblin with axolotl-like frills, standing with the demiguy flag in his hands. He is in the pose of Michaelangelo's statue of Bacchus, god of wine, merriment, and madness. One hand up as if to salute with a cup, body leaning and perhaps a little unstable. Olli is a gay demiguy, stepping away from the naturally ungendered state of his people to embrace masculinity instead. He is extroverted, loves a good party, and has definitely been a little over his depth with alcohol on many occasions. He knows this is a problem. He used to act rebellious because of it, trying to be cool and aloof, but he has since admitted the truth to himself and now openly seeks help. His trans lover, Zaire (seen in a previous post) has become a great support to him. Even though it may seem odd to use the pose of a god of wine for a character that is trying to overcome an alcohol issue, I still feel like the vibe of Bacchus or Dionysus fits Olli well. He is not only a god of wine, but also of pleasure in general, a concept Olli embraces. Wild joy, perhaps to the point of becoming a little feral, abandoning tradition for personal fulfillment. It is unusual for goblins to embrace a binary gender, even partially. Gendered pronouns do not exist in their tongue, only being used in cases where common speech needs to be used to refer to certain significant figures, such as a leader. It is also unusual for a goblin to take a lover outside their species, since most goblins live in fairly isolated places and all mate together seasonally, depositing their eggs in a communal nursery pool. Olli stands out on purpose.

Lastly, Sajak, an amphibious person with some fish-like features such as their finned ears and a barely visible dorsal fin. They are holding the genderqueer flag as they stand in a commanding pose, one foot on a rock, one arm held out as if pointing to something below them. This pose is taken from the central Poseidon statue in the fountain of Trevi. Their head, arms, and torso are covered in dark tattoos in abstract designs, and they also have a few natural dark stripes along their arms and legs. The obvious connection between Sajak and this statue of Poseidon is that Sajak is a fish person and Poseidon is an ocean god. If I could have thought of a more medical figure, I may have made a different choice in the art reference. Sajak is primarily a doctor, a healer. They are fairly well known and they were an important figure on their home island, though they did leave eventually. Even so, there is a certain vibe to Sajak that suits the image of a powerful and unpredictable oceanic god. They are steady, intelligent, and careful, but they can become fierce when their loved ones are under threat, and the intense focus they show in their work as a doctor can be intimidating to see. There is a feeling of hidden power within Sajak, just as there is in the ocean when it seems calm. Fish folk, whether bipedal and amphibious or fully aquatic, also fit under my category of "non-mammalian people who are just kind of genderqueer by default due to their biology not fitting into a binary".

#figure art#figure drawing#nonbinary#intersex#genderqueer#queer ocs#winks ocs#image description#accessible art#my designs#drow#lizard folk#elves#goblins#merfolk

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

You asked, so you shall recieve. Here’s my essay on neopronouns. I don’t know if it’s really good I onlyhave my teachers word but oh well.

My essay is an argument in support of neopronouns.

What exactly is a neopronoun? Pronouns, like she/her, he/him, and they/them are terms used to refer to people. Neo- means “new”, or “reborn”. Something that is rising in popularity, and coming back. “Neopronoun” is a term used to describe any set of gender-neutral pronouns that differ from the usual set of she/her, they/them , and he/him. Examples of neopronouns are ze/zir, fey/fem, and xe/xem. Unfortunately, neopronouns get quite a lot of undeserved hate from uninformed people.

Neopronouns aren’t just used in English though. Many languages around the word tend to be gendered, and don’t have any gender neutral pronouns, like they/them. In French, for example, there are only two types of words, feminine and masculine. There aren’t any gender neutral pronouns at all, so people create gender neutral pronouns, like ille/illes, which is a combination of the french pronouns “il” (he), and “elle” (she).

One of the main arguments is that neopronouns are just a “fad” or “trend” that has only come up recently. This is untrue. Neopronouns have been around for over two hundred centuries, actually. In 1789, the gender neutral “ou” pronoun was first recorded in literature, and the singular pronoun “a” was used as well. In 1864, the gender neutral “ze” pronoun was recorded in writing, and many other pronouns, such as “ne”, “heesh”, “er”, “ve”, “en”, “han”, “un”, “le”, “e”, and “ip” were also created, just to name a few. In 1884, thon/thon pronouns were created by American composer C. C. Converse as a combination of the phrase “that one”. And they were included in multiple dictionaries, though they fell into disuse. In 1912, Ella Flag Young created the pronoun set of heer/himer/hiser, probably as a combination of the traditional he/him/his and she/her/hers pronouns. Like thon/thon, hee/himer/hiser pronouns and ze pronouns have been featured in copies of dictionaries before, but have fallen into disuse. Although this is only some of the most prominent occurrences before the 2000’s there have been many more instances of people creating or going by gender neutral pronouns.

The second argument against neopronouns is that they’re “unconventional” and “unnecessary”. Plenty of people tend to ignore one of the most prominent reasons why neopronouns have sprung up again. Neopronouns have commonly been created and/or used by neurodivergent people, who feel a disconnect from the usual three sets of pronouns. People using neopronouns may want to avoid singular they/them being confused with plural they/them. Neopronouns may also express something about their gender and/or sexuality better than the traditional pronouns. Nounself pronouns are also a type of neopronouns. Examples would be bun/bunself, and star/starself. Those pronouns are just as important as abstract neopronouns and should be respected. The way someone expresses their identity is not your duty to police.

Many people argue you can’t just “make up pronouns” and forget that the traditional pronouns, he/him, she/her, and they/them, were also all made up. Originally, the only pronouns used were he/him. She/her pronouns were first used in the twelfth century, and the gender neutral pronouns were still he/him. In 1851, John Stuart Mill complained that there wasn’t a gender neutral pronouns besides he, stating that the use of it was making almost half the population (women) invisible. They/them pronouns were first used in the 17th century, followed soon after by what we know as neopronouns.

Pronouns are like names. Each person feels comfortable with a different name. You wouldn’t insist on calling every girl you met “Jane”, would you? Or every boy you met “Henry”. Pronouns are an important part of someone’s identity, just like names, and it’s important to respect that and use the correct pronouns. Overall, neopronouns are beneficial and beautiful, and deserve none of the hate they get.

Baron, Dennis “Nonbinary Pronouns are Older Than You Think” The Web of Language, October 13th, 2018

https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/25/705317

“Pronouns” UNF - LGBTQ Center

https://www.unf.edu/lgbtqcenter/Pronouns.aspx

“Neopronouns” LGBTA Wiki

https://lgbta.wikia.org/wiki/Neopronouns#Regional_Nominative_Pronouns

“Pronouns” Nonbinary Wiki

https://nonbinary.wiki/wiki/Pronouns#French_neutral_pronouns

#ahhhhhh#please tell me if its good or not#constructive criticism is appreciated#fbjzfbjsbgmsngmd#not wc#zin speaks

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Equal Relationship

The topic of romance in Little Women has been one of much contention since the novel’s conception. Ironically, decades later I venture on a journey to write about Jo March’s love life when Louisa May Alcott would probably have preferred literally any other topic about the character. But I’ve never viewed the novel or Jo’s story as a “romance,” but more so a story about four sisters with romantic subplots.

Little Women takes place in the mid-19th century amidst the backdrop of a divided America recovering from the harsh realities of the Civil War. Most women’s lives during this period are tied to the home “with little opportunity for outside contact” or most other kinds of experiences. The promise of women’s suffrage and higher education is still on the very distant horizon. Even when they are admitted to colleges, educators fear “their health [is] threatened” if they follow the “intellectual rigors of the male curriculum.” The “Cult of Domesticity” plays a significant role in shaping the lives of women as homemakers and child bearers (Hartman).

Louisa May Alcott’s deeply rooted connection with the Transcendentalist movement and its most prominent thinkers influences Jo March’s relationship with Friedrich Bhaer and how she describes him in the novel. Alcott’s progressive father was consumed by an unorthodox passion to educate his daughters at a time when a woman’s educational opportunities were limited. Her family lived near brilliant Transcendentalist reformers of the day, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne. She received lessons from Ralph Waldo Emerson and frequented Henry David Thoreau’s library to read great works of literature that sparked her interest in writing creative stories to support her family. Her early exposure to progressive ideas about the value of individualism had a significant effect on her writings, including the themes about family and ambition presented in Little Women.

Some speculate that Alcott may have based Friedrich Bhaer off of the Transcendentalist thinkers whose ideas so intimately spoke to her feminist perspective. For example, in the novel Friedrich is described as personable with an ability to attract people with his unique charm. Similarly, although Thoreau’s historical image is that of a hermit, he actually entertained guests, visited friends, and frequented the nearby town. In her journals, Alcott describes her admiration for Thoreau’s philosophies, calling him the “the man who has helped [her] most by his life, his books, his society” (Rogers). Furthermore, Emerson’s kind presence, musical voice, and commanding style of speech during his philosophical lectures captivated audiences. His 1838 speech at the divinity school in Cambridge was a passionate speech about self-reliance and religion (Brewton). Comparatively, Jo’s fascination with Friedrich’s impassioned speech about religion at the symposium is due to his “honest indignation” and “eloquence of truth,” which makes “his broken English musical and his plain face beautiful.” Additionally in the novel, Friedrich is described as having “a sympathetic face” and kind eyes. Alcott derives many of Friedrich’s tenderly masculine traits -- introversion, compassion, soft-spoken charm -- from the very men who were close family friends and who shaped her own philosophical views. Friedrich Bhaer is an unconventional romantic interest just as the men who shaped Alcott’s life were unconventional intellectuals.

Louisa May Alcott believed that most women were marrying for economic reasons. She loved luxury, but “freedom and independence more” (“Alcott”). In Little Women, Mrs. March believes that “[m]oney is a needful and precious thing,” but it isn’t “the first or only prize to strive for.” She would rather see her daughters as “poor men's wives,” if they are happy and content than “queens on thrones, without self-respect and peace.” Alcott herself never married -- perhaps because she could never find anyone who sympathized with her strong feminist ideals -- and the passage emphasizes the notion that marriage for the purpose of economic stability is a restriction and that marriage is not the end all and be all of a woman’s existence. Alcott uses the theme as a backdrop to Jo’s dynamic with wealthy socialite Laurie and penniless intellectual Friedrich. She emphasizes both characters’ social statuses throughout the novel to highlight more important distinctions about their personalities and their distinctive interactions with Jo. Where Jo and Laurie’s friendship represents a connection of two like-minded yet strong-willed young people trying to seek belonging in one another, Jo and Friedrich’s dynamic is one of equals in which Jo is challenged to push her limits and grow intellectually and spiritually.

Jo March is an ambitious, independent, strong-willed tomboy who wants to be a famous writer and seeks a life of deeper meaning than simply conforming to societal traditions of marriage and domesticity. Jo’s most passionate hobby is reading and in many ways it influences her intellectual curiosity about 1860s society. One day, Meg finds her sister “eating apples and crying over the Heir of Redclyffe;” it is Jo’s “favorite refuge.” Additionally, she somehow puts up with her job as Aunt March’s companion because the moment Aunt March is asleep or distracted, she devours “poetry, history, romance, [and] travels like a regular bookworm,” but she has to “leave her paradise” when she is called to do her duties.

Jo’s tomboyish nature and views against love depict her desire for non-conformity because to her conformity is synonymous with a broken family, loneliness, and the denial of her intellectual pursuits. She hates to think that she has to “grow [to] be Miss March, and wear long gowns” because it’s “bad enough to be a girl [...] when [she likes] boy’s games and work and manners.” Her insecurities about womanhood are emphasized when she tells Meg she wishes she could be a child for a long time. She observes that “Margaret [is] fast getting to be a woman and Laurie’s secret [that Meg and John Brooke are in love makes] her dread the separation that surely must come.” Nonetheless, she responds erratically when it becomes evident that John will take Meg away from her family -- she’s incredibly rude to John when he visits Meg, but she’s extremely ecstatic to see the regular ole’ postman. Jo wishes that they would hurry and get married because she’s uncomfortable with the idea that “Meg is not like [her] old self, and [seems] ever so far away from her.” Jo knows how things will eventually turn out, so she wants to make it a brief, sentimental separation for herself, instead of a drawn out, painful one.

Given Jo’s strong views on womanhood and her curiosity about upending social norms, she dreams of intellectual pursuits far removed from what is expected of mid-19th century women. Her ambition is to “do something very splendid,” but her “sharp tongue and restless spirit” are constantly “getting her into scrapes” when she ventures out into the world, removed from the comfort of her homely upbringing. She even admits that “her greatest fault is her temper” and “her greatest ambition is to be a genius.” It is precisely her restlessness that makes her happy and content when she is “doing something to support herself.” Furthermore, although long locks are the tradition for 19th-century women, Jo cuts hers to financially support her family. This illustrates the depth to which she is willing to go for her family in a desperate financial situation, but more importantly it emphasizes her continued disregard of social norms about physicality in favor of what she believes is right.

Jo and Laurie’s dynamic is characterized by childhood and innocence; he illustrates a brotherly figure who compliments her views about non-conformity while she represents the feminine presence he craves in his own life. Interestingly, Laurie admits to Jo quite early in the novel that he feels envious about the sisters’ bond with their mother. The motherless boy’s “solitary, hungry” look in his eyes affects her and she is glad to share her richness of “home and happiness” with him. This forms the foundation of Jo’s strong feminine presence in his life – he looks to her for affection and she responds with compassion. An important distinction between Jo and Laurie’s intellectual values is their contrasting views about education. Jo wishes she can go to college and notes that Laurie doesn’t look like he’ll like it. He agrees that he hates it because it is nothing but “grinding and skylarking” and he would rather enjoy himself in his “own way.” Jo desires a life of meaning to pursue her passions; she is intellectually curious and admires scholarly pursuits, whereas Laurie takes his intellectual opportunities for granted.

Although Jo and Laurie share some similar characteristics, such as their strong wills and quick tempers, they also have strong conflicting personalities. For example, Laurie complains that he feels like he’s living in the shadows of his grandfather's wishes and therefore has little motivation and is too lazy to try anything else. In response, Jo suggests he ‘“sail away on one of [his] own ships, and never [come back] until [he has] tried his own way.” While Laurie does eventually sail away for a time with his grandfather, he also goes to college beforehand to fulfill his grandfather’s dreams, not his own. On the other hand, Jo is rebellious and self-motivated from the beginning. She refuses to simply marry out of convenience and leaves her hometown the moment she realizes there isn’t much left for her there.

Jo wants to keep Laurie close to the family because she sees in him a kindred connection of masculine identity. This is one of the reasons she is constantly trying to match him with her sisters. When it becomes clear that Meg and John will be betrothed, Jo is frustrated because she “hates seeing things get all crisscross [...] when a pull here and snip there would straighten [things] out.” Jo’s reaction highlights her fears about a broken family and loneliness. Her plan to marry Meg to Laurie emphasizes the desire to keep her family together by marrying her sister to a friend, someone nearby who she deems trustworthy and complementary to her association with masculine identity. But, once Jo realizes that Laurie is getting too fond of her, she decides to pack up her things and travel to New York because she doesn’t believe they are suited for one another. Mrs. March is relieved and agrees that they “are too much alike and too fond of freedom,” not to mention their “hot tempers and strong wills,” which would thwart a relationship that needs “infinite patience and forbearance.”

Jo and Laurie’s clashing stubborn personalities are illuminated during the confession scene in which Jo insists she can’t be with Laurie while Laurie continues to badger her. After Jo admits that the main reason she went to New York was to get away from Laurie’s growing sense of attachment, he admits that it only made him love her more. He gave up “everything [she] didn’t like, never complained,” and hoped she would come to love him. Laurie’s confession is similar to that of a guy friend who has a crush on a friend and hopes that he will get her simply by being nice and hopeful. Furthermore, he tells her that if she says she loves the Professor, he will “do something desperate,” as if threatening her will convince her to love him. He then promises Jo that if she loves him, he would be a “perfect saint”; however, Jo rejects him because of fundamental differences in compatibility more so than his lack of saintly characteristics. Laurie continues to implore her to reconsider because “[e]veryone expects it. Grandpa has set his heart [on] you, your people like it, and I can’t get on without you.” It’s selfish that he insists she settle for what others wish for her than what she wishes for herself. If she followed his suggestion, it would negate her character as someone deeply rooted in individualism and upending societal expectations. Jo actually says as much in her response, “It’s selfish of you to keep teasing for what I can’t give you.” Laurie eventually travels to Europe, but not before sulking in his home while playing the piano tempestuously, avoiding Jo, and staring at her from the window with “a tragic face that haunt[s] her dreams.” Laurie’s attraction to Jo is natural, but his behavior after the rejection is self-destructive. He continues to make Jo the sole reason for his happiness. It’s the kind of response that hinders productivity and enjoyment of life, but also makes the other person feel guilty about their decision.

Unlike most of the other men in Jo’s life (of which there are very few as she hasn’t had much experience with men in general), she describes Friedrich’s physicality in greater detail and relays much of it in letters to her family back home. For example, early in their acquaintance, Jo hears him singing in German and notes that has the “kindest eyes [she] ever saw” and a “splendid voice that does one’s ears good,” but there is not a “handsome feature on his face.” Nonetheless she states that she likes him because “he [has] a fine head” and “[looks] like a gentleman,” alluding to her attraction to him being more cerebral than corporeal. When Friedrich advises Jo to study people’s characters to get a better sense about writing fiction, she studies his physicality and how it relates to his character -- she notes that he seems to “turn only his sunny side to the world,” that “time seems to have touched him gently” because of the kindness he bestows upon others, the “pleasant curves” around his mouth are due to his many friendly encounters and laughs with others, and “his eyes [are] never cold.” She thoroughly enjoys checking him out. Jo values character as a “better possession than money, rank, intellect, or beauty.” She ponders that if the qualities of “truth, reverence, and good will” are ‘great’ qualities, then her friend is “not only good, but great.” Her resolve on this matter strengthens every day and she values “his esteem, she [covets] his respect, and [she wants to be] worthy of his friendship.” When Friedrich later visits the March family, Jo notices that “he is dressed nicely and wonders if he is courting someone.” But realization soon follows her curiosity and she “[blushes] so dreadfully” that she “[drops] her ball” and goes after it to “hide her face.” Jo has progressed as a character by this time because the idea of Friedrich courting her does not disgust her as it once would have; instead, it makes her naturally self-conscious and fidgety.

Furthermore, it’s important to note how much of Friedrich’s tender masculinity aligns with Jo’s values about character. When Jo first notices Friedrich in the boarding house, he carries a “heavy hod of coal” all the way up the stairs for the servant girl and leaves with “a kind nod.” Jo likes such things and agrees with her father that such “trifles show character.” He leaves a good first impression on Jo; it also shows sincerity of character because he doesn’t know that she is observing him. At first she is perplexed why people admire Friedrich because he is “neither young nor handsome,” neither “fascinating [nor] brilliant,” and yet he is as attractive as “a genial fire” and people seem to “gather around him as naturally as about a warm hearth.” She concludes that it is his charisma, positivity, and good nature, not the superficiality of his looks or wealth.

Jo is reflective about society’s restrictions on her individualism and Friedrich is a natural companion because he represents the mentor figure who encourages her to think more deeply about her views. Friedrich’s philosophical background compliments Jo’s unique sense of feminist individuality. She greatly admires intellect and is proud to know that he was an “honored Professor in Berlin.” She observes that his “homely, hard-working life” beautifies the “poor language [master’s]” character much more in her eyes because he never speaks of his former esteemed life. Additionally, their shared sense of intellectual curiosity is illustrated during a moment on New Year’s Eve, when he gifts her Shakespeare’s works to study characters. She admits that “she never knew how much there was in Shakespeare before, but then again she never had [someone] to explain it to her.” One interpretation of this small moment is that it illustrates how much Jo has yet to discover about storytelling.

Moreover, she is entranced by Friedrich’s speech at the philosophical symposium as he defends religion and blazes with “honest indignation” and an eloquence that makes his “broken English musical and his plain face beautiful.” As he finishes his speech, she feels as if she has “solid ground under her feet again.” Jo not only agrees with Friedrich’s philosophical views, but is captivated by his delivery as well. It is a moment that coincides with her strong belief in individualism; she too wants to speak at this debate, but instead Friedrich gets the courage to do so and he speaks to her soul. Moreover, Friedrich reveals his strong distaste for sensationalist literature because he believes it sets a poor precedent for young people. Although he has a suspicion that Jo writes in her free time, he doesn’t know that Jo writes sensationalist literature or that she herself is uncomfortable about it. She doesn’t tell anyone about it for a long time. In order to publish her work, she is required to cut her sensationalist writing to one-third its original length. It receives mixed reviews after publication and she is generally jaded by the experience; she regrets not publishing the novel in its entirety. Jo is persuaded by Friedrich’s opinion on sensationalist literature and decides to stop writing pieces for the newspaper in pursuit of more principled stories. Soon after, she discovers that her passions lie with writing literature rooted in realism. There are some who would argue that Friedrich is patronizing here, but Jo also feels the same way and she discovers that she has more to offer the world than outlandish tales with no moral themes precisely through her interaction with him. Her efforts writing such stories are soulless and provide little personal meaning in her life and Friedrich’s strong opinions help her overcome her thankless endeavors.

Friedrich’s version of courting Jo is characterized by level-headed steadiness because he is unaware of her emotional and physical availability. Initially, he is suspicious that Jo and Laurie are more than friends when she wishes to introduce them. That night, he searches about the room “as if in search of something he [can] not find,” but he is still there to see her off at the train station the next morning. Although he likes Jo at this point, he does not act impulsively on his feelings because he is not sure about her feelings or her relationship with Laurie. Moreover, when he visits the March family after he realizes that something is amiss through Jo’s writing, he has a misconception that Jo and Laurie are a couple and “a shadow [passes] across his face” as he looks towards them. Friedrich’s realization is painful but he somehow manages to hide it and behaves amicably towards Jo and her family, which illustrates maturity and self-control. Additionally, he is confused by Jo’s “contradictions of voice, face, and manner” and her “half a dozen different moods” when he tells her that he is moving west. He doesn’t understand if she likes him or not and it’s only when she reveals her feelings that he also confesses he “waited to be sure if [she] was something more than a friend.” Jo confronts him about why he didn’t propose sooner, so he tells her that he thought she was betrothed to her friend, but he also wanted to have enough money to offer her a comfortable living. Friedrich’s courtship of Jo March is slow, steady, cautious, and level-headed. Due to his observant and compassionate nature, he is able to extrapolate Jo’s aversion to romantic pursuits and thus he approaches her mindfully with his own reservations.

Jo’s friendship and eventual romantic dynamic with Friedrich illustrates a relationship of equals in which she is able to fulfill her intellectual ambitions and overcome her fears about love and companionship. Their dynamic is set from their first interaction in which she unconventionally travels to New York alone as an unmarried woman. He then has a suspicion that she writes in her spare time and inspires her growth as a writer of passion instead of profit. Jo is captivated by the intellectual charm of such a man who delivers impassioned philosophical speeches at symposiums, who lives with integrity as a poor scholar in a foreign land, and has a unique charisma that attracts others to his presence. In return, Friedrich doesn’t expect anything to become of their friendship, even when he thinks Jo and Laurie are not a couple or when he’s confused by her contradictory range of emotions after he tells her that he’s leaving New England. And, neither does he feel threatened by her unique sense of ambition at a time when men’s ambitions are taken more seriously. He courts her like a patient and observant gentleman awaiting the final verdict about a woman’s romantic feelings, as if he is afraid to impulsively ruin a dearest friendship.

Friedrich Bhaer is no romantic, but neither is Jo. He is not one for passionate phrases about love, but Jo wouldn’t be impressed by such a companion. He has little wealth, yet Jo has lived her whole life in poverty so she is used to hard work. With the professor, Jo is able to live a life dedicated to her ambitions, where the social constructs of marital life need not necessarily apply, while also conquering her fears about love –that it doesn’t necessarily have to be about an unequal dynamic where the woman succumbs to a meaningless life of pure domesticity. Her dynamic with Friedrich is about being with someone who treats her as his intellectual equal, a kindred connection with someone outside of the loving but splintering family she was afraid to leave many years ago. In other words, it's hard to imagine a free-spirited woman like Jo, who has lived her whole life in the seclusion of her hometown with the safety and security of her family, not being captivated by an intellectually forward-thinking mentor type figure like Friedrich Bhaer. It is fitting that a woman so radical for her day forms a companionship with a charming, progressive intellectual.

Friedrich is Laurie’s foil in both his life experiences and characteristics. Laurie is an extroverted, wealthy socialite who has the privilege of pursuing intellectual interests, but would rather spend his time pursuing other things. He is impulsive and persistent in his pursuit of Jo. On the other hand, Friedrich is the poor scholarly professor in a foreign country who is soft-spoken and charming. He spends his time pursuing intellectual hobbies like attending philosophical symposiums. Both characters represent different aspects of Jo’s personality. Laurie represents her naiveté; he embodies her past and her too comfortable homely life. In contrast, Friedrich represents Jo’s growth into womanhood and a life away from the luxury of her comfortable home where she undergoes a feminist awakening about the kind of writer she can be. Her time with Friedrich also represents the challenges she is forced to confront regarding her own perspectives about the world and how she doesn’t necessarily have to forego love to life a fulfilled life. She can have both her intellectual ambitions and a companion who understands her.

Many have suggested that Laurie is a better companion for Jo. For example, some suggest that Jo and Laurie are good friends, have good chemistry, and know each other well. He wouldn’t constrict Jo’s ambitions, and therefore he would make a good life partner for her. While this is true, having good chemistry doesn’t necessarily translate to a successful romantic partnership. There are many people who we have good chemistry with in our lives, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they would be great life companions. Although they know each other well, Laurie doesn’t completely internalize Jo’s unromantic, stoic personality; he reveals this when he complains that she “won’t give anyone a chance” and “doesn’t show the soft side of [her] character.” He is needy for attention and love while Jo is more of an independent, free-spirited person who wouldn’t be able to provide that kind of love for him. Furthermore, just because he wouldn’t inhibit her ambitions, doesn’t mean that her ambitions wouldn’t be thwarted by marrying him and fulfilling her marital duties in wealthy society.

Another perspective is that Jo would have been better off single because she is a strong, independent woman and Friedrich was simply shoved in so Alcott could fulfill a romantic subplot. Although being single is what Alcott preferred for Jo, it contradicts Jo’s characterization in the novel. Jo is strong-willed, independent, and extremely ambitious and while all these things are great reasons for her to have a fulfilled life without the construct of marriage tying her down, she is also extremely averse to love and marriage because she fears the loneliness that it brings. She’s seen what these institutions do to her family -- they break it apart and it can never be completely repaired again because all of the fragments (the married sisters) are in different places (their married homes). By the end of the novel, Jo’s reality is one of loneliness and isolation -- the very things she feared all along. The inevitable happens. Moreover, Jo is in search of a belonging where she is able to be herself completely, but not feel the burden of societal normativity upon her shoulders. With Friedrich, she gets the best of both worlds -- she is able to pursue her intellectual passions as a writer because he is also passionate about philosophical ideas, they share similar world views about individualism, and she gets to have him as a friend, lover, and companion.

Alcott didn’t focus much on Jo and Friedrich’s dynamic, but she also didn’t focus much on the romantic stories of the other sisters as well. Romance was always going to take a back seat to the strong themes about family and womanhood presented in the novel, but it’s disingenuous to claim that because Alcott was required to pair Jo off with someone at the end, she decided to simply insert Friedrich as a subplot device and thus their relationship is random and forced. Regardless of whether or not one believes that Alcott succeeded in illustrating a believable romantic storyline, she did create a distinct character who compliments the unconventional heroine in many of the subversive ways a unique dynamic like Jo and Friedrich could have been depicted. She addresses Jo’s ambitions, her fears, her indifference to marrying for wealth or power, and her deep sense of intellectual curiosity -- in other words, it’s hard to imagine how such a radical character like Jo (for the times that she represents) could have ended up with anyone other than an intellectual type, someone who could continuously challenge and inspire her (as Friedrich does with her sensationalist writing, which inspires her to find where her passion lies). By introducing Friedrich’s character, Alcott wanted to make a bold statement and subvert societal expectations about what a potential romantic interest could look like. Therefore, it’s quite possible that she spent more time crafting his character. In fact, she seems to have thought about the character quite purposefully and thoughtfully.

Although Alcott didn’t intend for Jo to be paired off at the end of Little Women, it’s unlikely that she would half-heartedly insert a romantic interest in order to fulfill a requirement. By making Friedrich Bhaer a counter stereotypical character, one who subverts conventional stereotypes about masculinity, she was very intentional in the kind of lesson she wanted to impart about social class, intellectualism, unconventional romances, and a relationship founded on equality. Jo’s dynamic with him represents the subversion of societal norms; they are intellectual equals. With Friedrich, she remains an ambitious, impassioned individual with greater clarity about how to focus her passion for writing. On the other hand, Laurie represents Jo’s innocence and comfortable family life. They are two stubborn and alike individuals who seek a belonging in each other – Laurie seeks her feminine presence while Jo wants to live vicariously through Laurie’s masculine energy. Alcott never married, but she created a romantic interest who understood Jo while many others stood by shell shocked. It’s through Friedrich Bhaer that Alcott revealed a part of herself and her ideals.

**A special thanks to @fairychamber for the thought-provoking discussions and review of this piece.**

Sources

“Alcott: Not the ‘Little Woman’ You Thought She Was.” NPR: Morning Edition. 29 Dec. 2009.

Alcott, Louisa May. Little Women. DigiReads Publishing, 2015.

*Azelina. “Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Moods’ and Transcendentalism.” Wordpress. 2012.

Brewton, Vince. “Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882).” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

*Campbell, G. Jacqueline. “Gender & The Civil War.” Essential Civil War Curriculum.

Hartman, W. Dorothy. “Lives of Women.” Conner Prairie.

Rogers, Olivia. “Louisa May Alcott’s Transcendentalism.” Live Ideas Journal. 19 Mar 2019.

#little women#jo march#friedrich bhaer#jo and fritz#theodore laurence#teddy laurence#laurie#jo and laurie#louisa may alcott#19th century literature#meta#essay#little women 1994#little women 2019#little women 2017#little women 1949#saoirse ronan#timothee chalamet#louis garrel#greta gerwig#gabriel byrne#wynona ryder#jo x friedrich#jo x laurie#henry david thoreau#ralph waldo emerson

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not Casual At All: Everybody Get Some (Biadore) - Miss Alyssa Secret

“You’re the only one I can trust not to yell, ‘not today, Satan!’ right before you come,” had been Roy’s explanation when Danny brought it up.

Adore thinks she’s going to have to settle for (admittedly cute) trade, but she’d much rather be having sex with Roy. Luckily, there’s a surprise waiting in her dressing room, followed by an absolutely filthy blowjob in the shower and cuddling.

A/N: Admittedly, I wrote an entire fic to set up a blowjob/mirror sex. Contains very brief Adore/OMC, and Danny’s resulting vulnerability about the situation. -MAS

********

Adore finished out the number flat on her back on the stage, the lucky fan she’d pulled up to make out and grind with cradled between her raised knees. She closed her eyes and took a few seconds to enjoy the applause and shouting, chest heaving as she tried to catch her breath.

The boy on top of her was very politely holding his weight off her torso, and she let him help her up. He’d been fun, flushing dark red when she pushed him down in the chair and straddled his lap but readily groping her chest and crotch once invited. A good kisser as well, something Adore could appreciate, evidenced by the fact that he was now wearing more of her lipstick than she was. She watched as he tried to discreetly adjust his hard on, gathering his wallet and cap from where they’d tumbled when she pulled his shirt off.

Giving him one last kiss, she murmured, “Come see me after?” in his ear, pleased when he bit his lip and nodded.

”That was fucking hot!” she yelled into the mic, evoking another round of wild screams before introducing the next song.

The music started and she lost herself in the song, green hair whipping back and forth. There were just a couple more to go, and then she’d be done for the night. Performing always made her horny, so with luck, the boy would find his way to her as well.

His dark eyes had caught her attention when she scanned the crowd to make her selection. Intensely masculine features, short curls under a hat, he had pushed all of the right buttons. He was slender with a wiry build that she couldn’t wait to feel pinned against a wall, or maybe the couch in her dressing room.

Adore loved finding the beauty in everyone, never settling on one standard of appearance. On the other hand, she was well aware that the boys she’d been finding most attractive resembled a certain someone, although the fans didn’t seem to have picked up on it.

Yet.

Roy himself seemed highly amused when she admitted most of the trade reminded her of him. (“As long as it’s me and not Bianca, I’d be worried if you were fucking clowns.”) She’d much rather be falling into bed, over vanity tables, or against doors with him. Unfortunately, Bianca was booked halfway around the world, and she was stuck pulling boys who were quite attractive and charming, but still poor substitutes. Getting off was fun, but she missed the companionship and post-coital conversation that consisted of more than race-chasing or celebrity worship.

After two encores, she bounced off the stage, buoyed by the audience’s energy. Blotting her face, she grinned when she saw him waiting for her next to a severely unimpressed security guy.

”Wanna party with me?” she winked at him, pulling him by the hand towards the backstage corridor. Once through the doors, she pushed him against the wall and let him grab a handful of her ass.

“Forgot to ask,” she purred, “what’s your name?”

”Uhhhh…” He reddened in embarrassment, and she patiently waited for his upstairs brain to come back online. “Ummm. I’m Ian.”

”Nice to meet you, Ian.” She pressed a thigh between his, feeling his clothed erection against her hip. “Wanna see my dressing room?”