#japanese linguistics in anime

Text

Chapter 359: “The one closest to Izuku Midoriya”

First on the docket today is the deep dive you all deserve.

The official English translation for chapter 359 is not yet published, but everyone is already freaking out over it. I’m here to tell you: it’s okay, relax. No, really, don’t get worked up.

I mean, sure, there have been plenty of odd choices in the My Hero Academia English translation, that’s fair. And if MHA is your hyperfocus du jour, the nuance lost in translation can be pretty frustrating. Heck, I’m a literary analysis and criticism ultranerd, so I’m right there with you on the righteous indignation front.

But you must direct your fury at the correct target. I’m telling you right now this isn’t a hill worth dying on, and I will happily go into my reasoning in disgusting detail. Save your mental health and let me tell you all about a special little dialogue bubble and how it’s definitely gonna get butchered in translation and there’s nothing any of us can do about it. It’s not the first victim of this problem, and it certainly won’t be the last.

The truth is, translation is hard. And it’s all the fault of one evil overlord to be revealed in due time.

Hopefully my explanation will put you at ease and help you through all the weird translations we’ve had and will continue to have in this story. And by put you at ease I mean let you in on my little secret that I cope with on an hourly basis:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. The literal translation in way more detail than was ever necessary

II. The evil overlord at fault

III. Relationships don’t work like that

IV. Except for when they do

V. All For One likes his narratives

I. The literal translation in way more detail than was ever necessary

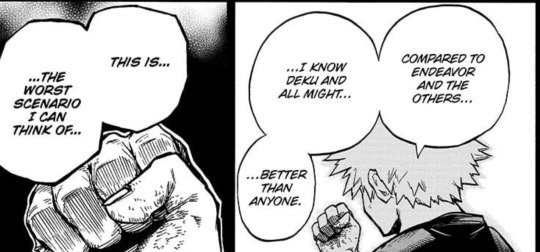

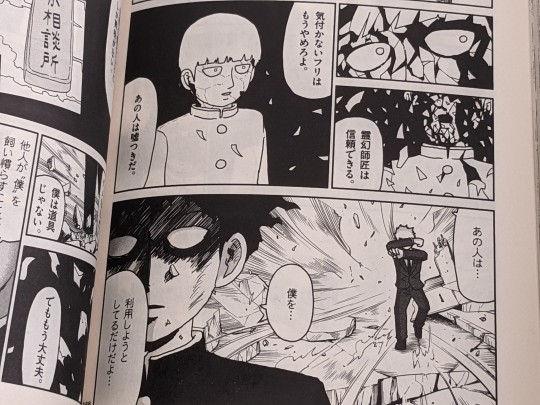

Here it is, the line that you’re all losing your marbles over.

From my initial translation:

“If there is one point of interest [I have in you, it’s that] you are the one closest to Izuku Midoriya.”

ただ一点興味があるとすれば君は緑谷出久と最も仲が良い

ただいってんきょうみがあるとすればきみはみどりやいずくともっともなかがいい

tada itten kyoumi ga aru to sureba kimi wa Midoriya Izuku to motto mo naka ga ii

And now presenting your painfully descriptive translation of each bit.

Speech bubble 1:

tada = just/only

itten = one point

Speech bubble 2:

kyoumi = interest

ga = grammar particle indicating a subject of a phrase or sentence

aru = to be (nonliving things)/to have

to sureba = grammar pattern meaning “in the case of [preceding statement]; assuming [preceding statement]; if A then B“

Combined speech bubbles 1-2:

Literally: “Assuming just one point of having interest,”

Contextually: “If I have just one point of interest in you,” where all the pronouns are implied by the context of the previous conversation.

Speech bubble 3:

kimi = you

wa = grammar particle indicating the topic of a statement

Speech bubble 4:

Midoriya Izuku = that’s his name don’t wear it out

to = grammar particle indicating an inclusive conjunction such as “with” or “and”

motto mo = adverb that means “most; best; extremely” (the adjective it modifies is “ii” further down)

naka = relation/relationship in the general sense; it’s worth noting this is the first kanji in the word “nakama,” which is worth looking up if you’ve never heard it before but have watched any shounen anime in your life

ga = grammar particle indicating a subject of a phrase or sentence

ii = adjective that means “good” but has versatile utility, particularly in idiomatic expressions

-->naka ga ii = close/intimate/good relationship

Combined speech bubbles 3-4:

Literally: “As for you, with Midoriya Izuku the most good relationship.”

Contextually: “You are the best relationship with Midoriya Izuku.”

...

...

...

I think you can see how tricky this particular line would be to translate into English and have it make sense.

"Naka ga ii” is basically on the whole an adjective. There is no adjective in English that means “(most) good relationship,” and if there was, it’d be difficult to get across the generic sense of the word “relationship” without some weird English-only connotations. No matter what, you’d be hard-pressed to find any two translators who would treat this sentence the exact same way.

So the best I can do is explain my own logic to help you follow along with another translator’s logic, because we’re all gonna have different meanings we’re trying to preserve.

Here was the note I left on my first translation:

(Note: Literally, “motto mo” means “most” and “naka ga ii” means “good or intimate relation/relationship.” It’s not that this is necessarily a romantic or platonic phrase. AFO is just pointing out that the deepest, most important relationship Izuku has is with Katsuki. Take that how you will.)

I knew no matter what I was going to lose some nuance in English, so I left the above note to point out the meaning in the grammar I was trying to preserve. This allows you to come to your own conclusions about my translation and Horikoshi’s meaning. I said “Take that how you will” because...well...I knew everyone would take it however they wanted to lol. I don’t have any interest in setting your expectations when it comes to shipping or whatever, even if I have my own interest in the relationship between Izuku and Katsuki. I think it would be dishonest if I didn’t point out the vagueness of the word “naka” because ambiguity in prose is...fun to dissect.

There are plenty of “official” translations in MHA I dislike, and I have fizzled and fumed over many a “bad choice” in that regard. But it wasn’t Caleb’s name I was cursing as I shook my fist at the sky in anger.

II. The evil overlord at fault

The perpetrator I curse is the English language.

Shit gets lost in translation. There is no avoiding that fact.

I do these debatably “literal” translations precisely because MHA doesn’t come with a page on the side explaining the context like a Shakespeare play might. You have to understand, I do not envy the official translator’s job at all. It is quite the task to try to capture the complete meaning of something in any other language let alone something in Japanese and properly translate it into English in a way that sounds natural and makes complete sense. Japanese has different grammar for levels of politeness, and those same patterns can be polite or rude just depending on who is talking to whom. Japanese drops pronouns and shit like that all the time. Japanese considers plurals a suggestion. Japanese has all its own little idioms and social contexts that a dictionary will never be able to explain succinctly. You think I’m such an English wordsmith I can figure out that impossible translation puzzle? Screw that.

I hate the “bolster” translation in chapter 318/321, but not because I hate the translator. I hate it because I can’t think of a good translation either. The word in question means to “complement/complete something that is broken.” What do you do with that in English? “Izuku Midoriya needs someone who can restore his broken form to completion and complement his strengths so they make up an all-powerful superhero icon?” Who the hell talks like that? Other than my awkward ass, I mean.

There are plenty of examples like that, but I might as well just go back to the original sentence in question. I don’t have a perfect English translation for chapter 359. All I can do is explain what I was trying to preserve in my choices:

“You are the one closest to Izuku Midoriya.”

As I explained before, “naka ga ii” doesn’t label a particular type of relationship, so I can’t use “friend” if I want to preserve that vagueness, and I do. I do want to preserve it. Not only because I think it’s good to have ambiguity in prose or because I think it’s good to not necessarily put every relationship into a neat little box but because there is a cultural context point that is ever-present throughout the entire MHA manga: the fact that Izuku and Katsuki are childhood friends.

“Childhood friends” is another awful translation, because there really is no English equivalent for osananajimi, which is the real word everyone uses to describe them. Please look this up. I don’t have time to go into the nuances and intricacies and implications and tropes of this word. Just know that “friends” is...reductive of the true meaning here. Osananajimi carries with it an implication that the “childhood friends” know each other on a special level because they grew up together before developing their sense of social personas, in-groups and out-groups (honne and tatemae play in here a lot), and such. It doesn’t mean that this relationship is necessarily romantic (although it’s used a lot in romantic tropes); it’s just an important type of relationship for which the English language doesn’t distinguish and many western cultures don’t have any context. It explains why Izuku calls Katsuki “Kacchan” still, and why characters like Shouto make assumptions in the sports festival about how well they must know each other, and why the story treats their “childhood friendship gone wrong” as ironic and a bit of a subversion.

But while I want to avoid the word “friend” because of the “childhood friends” issue, the fact remains that all official English translations do use the phrase “childhood friends,” so the word “friend” would at least be cohesive with their own previous translations. And I begrudgingly don’t have a better English translation than “childhood friends” to use, so I can’t hold that against anyone.

I also have to decide what “ii/good” means in this context. “Most” + “good” = “best” in English, but is that what the story is really trying to convey here? My translation note says “AFO is just pointing out that the deepest, most important relationship Izuku has is with Katsuki.” Is Katsuki the person Izuku cares most about, more than anybody else? Is that what you think I’m trying to convey?

No, actually.

III. Relationships don’t work like that

I don’t think most people are doing this, but if you’re actually out there somewhere arguing over whom Izuku loves more, you’re no better than AFO. No one thinks in these terms in normal life. Izuku doesn’t keep track of his Love Relationship Stat with everyone in his life and measure on an absolute scale who matters the most to him. Be careful, because I see people getting dragged into this debate without realizing it, and what’s usually happening is that the arguers are talking over each others’ heads. You’re not talking about the same things.

Izuku has different relationships with different people, and of course he cares about them all. He cares deeply about many of them, in fact.

“You are the one closest to Izuku Midoriya.”

I thought long and hard about this translation since I claim to translate as literally as I possibly can. I decided that in the context of “osananajimi” and “naka ga ii,” Horikoshi was probably going for two things.

Number One: How well Izuku and Katsuki know each other compared to anyone else.

Osananajimi (“childhood ‘friends’”) and naka ga ii (“[most] intimate relationship”) don’t necessarily mean that the relationship in question has to be a romantic one, or even a good or positive one. These terms are predicated on how well the two people understand each other. MHA demonstrates that even when Izuku and Katsuki are on bad terms there are just some things they intuitively get about each other that no one else seems to. The bond Izuku and Katsuki have is unique and nothing they’ll ever be able to recreate with anyone else just by nature of their having grown up together.

The best English word I could think of for this was “close.” But even that has some connotations in English that could just be baggage in this case. Still, it’s the best I’ve got.

So when my note gave the shorthand explanation of “deepest,” I was referring to the amount of time and understanding between these two. I don’t have a metric stick to hold up and compare their relationship in quantifiable terms to any other. There are things Izuku’s mother will know about him no one else does. But the nature of that relationship is just...different from this one.

It’s not a zero-sum game. Relationships don’t work like that.

IV. Except for when they do

Number Two: Horikoshi is writing a story, and he has character sheets and notes.

Regarding my translation note describing their relationship as Izuku’s “most important,” I do not mean to imply that all of Izuku’s other relationships are extraneous fluff that can be cut away, and if anyone dared to take it that way, like...please touch grass or something. Afford me a tiny assumption of good faith here, please.

Whether or not you accept this interpretation, it is absolutely valid to interpret Katsuki as Izuku’s most important relationship in the narrative. This isn’t about “whom Izuku loves most;” it’s about what the story chooses to focus on. The narrative places a heavy focus on their relationship, and to deny that is...just annoying, because you’re not proving anything by saying “nuh-uh!” There is support in the text for this interpretation. It doesn’t have to be your interpretation, but it’s there and viable and anyone who takes it is justified in doing so. Your literature and writing classes in school called those essays you were forced to write “persuasive essays” for a reason.

Horikoshi could be out here to just spell it out in plain, blatant terms that the relationship between Izuku and Katsuki is center-stage to the story, and in that sense, yeah, it is the most important. TO THE STORY. TO. THE. STORY. That doesn’t cheapen the importance of any other relationship. It’s just a big focus. Like how Izuku is the main character. You don’t have to argue someone else is the main character if you’re not interested in Izuku or don’t like him or whatever. There are other characters, and they are there and they are great and you can love them more too! We call them “favorite characters” for a reason!

“You are the one closest to Izuku Midoriya.”

I chose this translation because it accomplishes the things I think are most important: (1) it doesn’t label the relationship; (2) it describes the facet of their relationship that is most important, how well they understand each other where no one else does--their “closeness”; (3) it--

Oh yeah, there’s a Number Three.

V. All For One likes his narratives

IT’S OMINOUS AS FUCK.

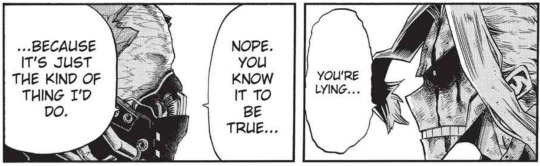

Horikoshi ain’t the one who said the line. All For One/Shigaraki did.

Did you notice “naka ga ii” is the final word in the whole phrase? The dramatic emphasis is on the adjective that means “close[st] relationship.” Why would AFO!Shiggy say this?

To scare the ever-loving shit out of Katsuki.

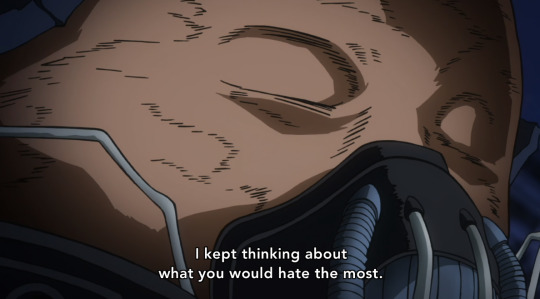

AFO does this shit. All Might is a hero who saves everyone, and AFO tried to use injured bystanders against him in Kamino--but even that didn’t work. All Might kept his cool. AFO had to think and plot and scheme for a long time to figure out whom he could use against All Might, and Tenko Shimura was the one who finally took a bit of All Might’s smile away. This is AFO’s modus operandi. So of course he’s been on the lookout for someone he could use against Izuku, too.

Izuku loses control of his emotions when Katsuki is in danger. That’s all there is to it. That’s all AFO cares about. In his long history of toying with and manipulating people, he’s decided that this is the reaction from his enemies that gets him the best results: Find the enemy’s weak-point and poke it relentlessly. Watch them squirm. Keep them from thinking clearly.

It’s always been leading to this.

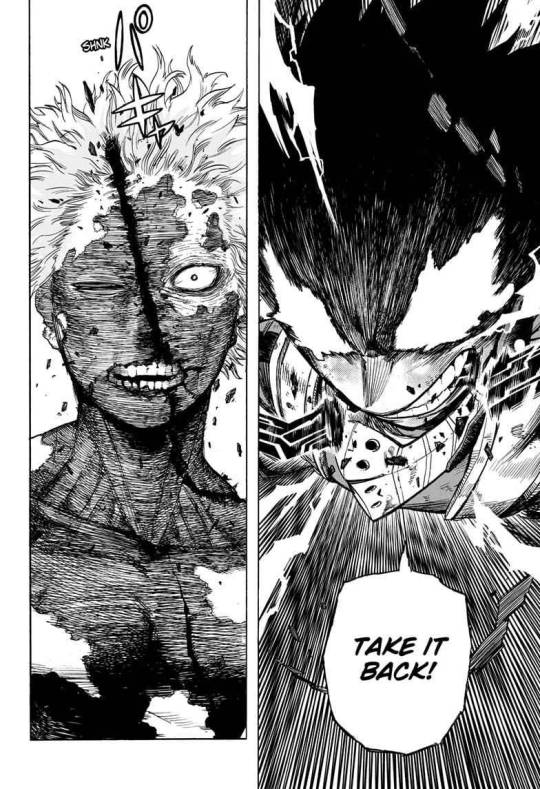

The real question is: Did it work?

Is Katsuki scared? Is Izuku gonna freak out?

Whacha gonna do, Blasty?

#mha 359#bnha 359#mha spoilers#mha manga spoilers#my hero academia spoilers#my hero academia manga spoilers#katsuki bakugou#izuku midoriya#all for one#AFO#bakudeku#not shippy but like this is important to their relationship#but also shippy because i don't discriminate#i merely analyze#japanese linguistics in anime#meta

349 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birds are famous for communicating vocally, but many have other options, too. Some communicate by dancing, for example, or by showing off their feathers.

And according to a new study, at least one bird species does something more often associated with humans and great apes: symbolic gesturing.

A songbird called the Japanese tit (Parus minor) uses fluttering wing movements to signal "after you," the study's authors report, similar to the way humans extend one open hand to let another person go first.

Continue Reading.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Inarizaki's Kansai Dialect

Japanese Dialects are split into Eastern and Western, with the Standard Japanese dialect being Eastern (Kanto region) and Kansai region dialect being Western (eg. cities of Osaka and Kyoto, and of course Hyogo prefecture- where Inarizaki is from). The pitch, tone, and stressing of the sounds is different from standard Tokyo Japanese so you should be able to hear the difference in how the Inarizaki members speak even if you don't know any Japanese.

just in case yall didn't know, Suna is the only member on the team that does not use Kansai dialect as he was scouted from Aichi prefecture, so he basically just speaks in the standard dialect

Some linguistics of the dialect that may or may not be heard in the show:

"ya" ending vs the standard "da" ending.

Kore kirai ya. vs Kore kirai da. (I hate this.)

the use of the "h" sound instead of "s"

Han vs standard san (honorific suffix, not really used anymore)

Negation suffix "-hen" instead of the standard "-nai".

Taichou kanri dekitehen koto, homen na. vs Taichou kanri dekitenai koto, homen na. (Don't compliment him when he's obviously not taking care of himself.)

verb "oru" vs the standard "iru".

Dareka ga mitoru yo, Shin-chan. vs Dareka ga miteiru yo, Shin-chan.

(Someone's always watching, Shin-chan.)

verb "temau" vs standard "teshimau"

Naitemau yaro! vs Naiteshimau darou! (You're gonna make me cry!)

Negation "suru" verb becomes "sen" instead of "shinai".

Ki ni sen dee. vs Ki ni shinai yo. (Don't worry about it.)

Some words that are different in Kansai dialect:

Honto becomes Honma (really)

Sodane becomes Seyade (thats right)

Nande becomes Nandeyanen (why)

Totemo becomes Meccha (very)

ii becomes ee (good)

"aho" means stupid in Japanese, but apparently in the Kansai dialect calling someone an "aho" is actually a compliment?! (even though it has the same definition)

Overall, I could watch the Karasuno vs Inarizaki episodes a hundred times just to listen to Inarizaki's dialect and how different it sounds to the rest of the characters in the entire show.

Although Karasuno speaks in the standard dialect (which isn't very strange since Miyagi is a suburb close enough to the Kanto region), theres a few lines here and there where one of them says something using the Tohoku dialect (the dialect that would be used often in the rest of Tohoku, such as Aomori).

But that can be a separate post for another day!

(I especially like Kita's voice, thank you Nojima Kenji.)

#haikyuu#inarizaki#japanese linguistics#japaneselanguage#japanese#kansai#kita shinsuke#miya atsumu#miya osamu#miya twins#suna rintarou#aran ojiro#ojiro aran#akagi michinari#anime#anime and manga#linguistics#dialect#kenji nojima#japanese language#karasuno#tokyo

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are anime translations so bad?

Disclaimer: I have never done any professional translation, and I don’t watch dubbed/subbed anime very often. But recently I watched a few episodes of subbed Demon Slayer at a friend’s place, and I noticed how bad some of the translations were. It reminded me of my childhood, watching subbed Ghibli movies and thinking “that english sounds weird”. As a kid I thought it was an unavoidable part of translation, but now that I can speak Japanese, I realise that we can do so much better with translations!

This post is my attempt to identify what a “bad” translation is, and hazard some guesses at what mistakes translators make that lead to these bad translations.

Examples are from Ranking of Kings, episodes 10 and 11. Screenshots taken from Crunchyroll.

What do I mean by bad?

Reason 1: They don’t sound like natural English.

If a character in an english cartoon said some of the stuff that characters in anime say in translations, it would sound very unnatural. Anime-translation english is unnatural and awkward sounding.

ダイダ様、久しぶりに街に出てみますか?

Price Daida, it’s been a while, so why don’t we go down into town?

This example sounds awkward. What’s with the random “so” in the middle of the sentence? No one in English media talks like that. If you just remove the “so” and replace it with a full stop, we get a much more natural sounding sentence.

Price Daida, it’s been a while. Why don’t we go down into town?

Or even something like this:

Price Daida, why don’t we go into town? It’s been a while since you’ve been down there.

Reason 2: They don’t fit the character.

This screenshot shows the character Kage speaking (the black blob). He has a character trait of being kind of immature and almost never using polite Japanese, even to royalty, which is very disrespectful. The original translation makes him sound so formal! Kage is supposed to sound like a 15 year old who tries way too hard to be rough and intimidating. Can you imagine someone like that saying “You may say those things”?

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけど、違うからね!

No, no, no! You may say those feel-good things, but reality is different!

It doesn’t preserve his characterisation at all. Way too formal and not juvenile enough! A better translation would be:

No, no, no! Nice motivational speech, but they’re just words!

The devil’s advocate & descriptivism

Now, I’ll preface this by saying I am a hardcore descriptivist. I’m not saying that these translations are wrong, or that the resulting English is incorrect English. What I’m saying is that they do not achieve the goals of a good translation, those goals being preserving what is being said and how it’s being said.

It could be argued that by now, anime translations have become a new dialect of English. Anime fans have come to expect the awkward-sounding phrasing, and instead might see natural English as unexpected. This is a fine rebuttal of my first point (it sounds awkward) but not of my second point (speech-pattern-based characterisation is often lost). Even then, anime translations are not exclusively for established anime fans. First time viewers may be put off by the unnatural language choices and strange turns of phrase. “Anime is cringe” they might say, and they wouldn’t be wrong. A good translation should be understandable to the entire target audience, and first time or casual viewers certainly make up a large portion of that target audience.

Why do the translations end up so bad?

They err on the side of direct translation over meaning-based translation

Often, it seems like the main nouns and verbs in the sentence get translated verbatim, and the rest of the translation is forced to bend around those. In addition, they do not consider how a similar sentiment might be phrased in english. Even if it’s a japanese way of saying something, they preserve the individual words instead of changing the whole sentence. Let’s look at the Kage example from before:

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけ���、違うからね!

No, no, no! You may say those feel-good things, but reality is different!

I’ve coloured the text so you can see which pieces got translated separately. In this example, basically every word is being translated separately. Now let’s look at my example:

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけど、違うからね!

No, no, no! Nice motivational speech, but they’re just words!

I’m translating the entire middle verb phrase as one atomic piece of meaning. It’s not individually important that, for example, the specific word 言ってる was used, so it’s not important that I translate it directly to the word “say”. What is important is that Kage is saying that Despa is saying some nice stuff, but it doesn’t change the facts. I have a feeling that the more you can group words together and translate them as a whole phrase, the more natural the translation ends up sounding (and the more characterisation you can preserve).

They use weird words, due to dictionary translation

Let’s look at another example:

兄上は弱者だと、どこか甘えていないか?

Aren’t they sort of spoiling Brother, just because he’s a weakling?

In this example, the word 弱者 is translated as “weakling”. “Weakling” is a pretty rare word to hear outside of anime. That’s probably the best direct translation if we’re looking at the word 弱者 out of context. However, words always appear in context. Both times the word 弱者 is used to refer to a person in this episode, it’s used to refer to disabled people (Bojji, who is deaf, and a citizen, who is both blind and deaf). The citizen is actually not physically weak, in fact he looks pretty chunky and strong, so 弱者 is not being used to refer to his physical strength, only his disability. The English word “weakling” strongly suggests physical weakness, so I don’t feel like it’s appropriate here. Instead, I feel like a more appropriate translation would be:

Do you think Brother gets special treatment, just because he’s so pathetic?

Daida is immature and heartless at this point in his character. He has contempt for both Bojji and the citizen, and sees them as weak, but he also feels pity for them. I think the word “pathetic” sums up his emotions for them much better than the word “weakling”, as well as not coming loaded with the incorrect “physical weakness” connotation.

As a side note, you may have noticed I translated the first part of the sentence differently too. That’s another example of how (in my opinion) grouping words together to translate a phrase as a whole results in a much more natural phrasing.

They try to preserve the original grammar

An important skill to have when translating is knowing which aspects of the phrase are important to preserve in translation, and which parts are not important. Word order and grammar are almost never important enough to preserve.

ダイダ様こそ、選ばれた人間。

Prince Daida, you are one who is chosen.

In this example, the past tense verb 「選ばれた/chosen」modifying the noun 「人間/person」 seems to have been determined to be important to preserve by the translator, which leads to the awkward phrasing “one who is chosen”. In reality, the minutia of the original grammar is not important to preserve - we can translate 選ばれた人間 as a set phrase rather than translating the words individually:

Prince Daida, you are one of the chosen few.

Again, we can see that the translation is improved by grouping words together and translating the phrase as a piece of atomic meaning!

Anime translation is a naturally restrictive medium

For dubs, the characters’ mouth movements need to match up. This really narrows down the possibilities of translation options. It means that sub-optimal word choices may be used, and the rhythm of speech may be forced into an odd speed in places.

For subs, although the syllables and mouth movements don’t need to match up as perfectly as they do in dubs, the subtitles still end up needing to be applied over the same moments of speech. However, often, if the given situation in the anime was to be completely reframed in English, maybe no one would have said anything at that moment. There are times when someone would say something in Japanese that you would expect someone to not say anything in english.

デスパー:弟子の悪口は許しますけど、私の悪口は許しませんよ!!

カゲ:逆でしょ!!!!

Despa: You can insult my apprentice, but I won’t let you insult me!

Kage: You’ve got it backwards!

In Japanese comedy, the role of ツッコミ (best translation is “the straight man”) is ubiquitous and plays the part of a laugh track - telling audiences when to laugh. In this case, Kage is playing the part of ツッコミ by pointing out that what Despa has said is the opposite of what you’d expect him to say. In this example, I feel like if this was an English cartoon, Kage wouldn’t have said anything. English speaking comedies generally expect/trust audiences to get the jokes without them being explicitly pointed out. I feel like this shows how attempting to fit subtitles to every spoken phrase can lead to slightly unnatural turns of phrase, since the translator is attempting to fit some speech into a place where there wouldn’t have been any in the first place. In my opinion, the best “translation” for the above would have been to cut the 1 second clip where Kage butts in with his line altogether.

———

Again, I should reiterate that I’m not a translator. I’m very keen to hear counter-arguments if you disagree with what I’ve said! Translations have got me really interested recently and I’m hungry for more opinions.

#langblr#japanese language#japanese#japanese grammar#learning japanese#linguistics#translation#language acquisition#language learning#language#anime#ranking of kings

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

look at this!

it's a stylistic mix of japanese script and arabic script! it looks so cool!!

#i noticed when i watched the first ep but i havent seen any post about it. it's so cool!!#bucchigiri#bucchigiri?!#anime#animanga#linguistics#languages#language#japanese#arabic#farsi#persian#linguistics tag#moralgayness

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

I noticed that, in the English dub, the ADA refers to Tanizaki by his first name rather often. It's actually pretty rare to hear his last name in the dub, and I wish I knew why.

It can’t be for the simplicity of referring between him and his sister, since everyone calls her Naomi in both versions.

It’s not a logistical (“mouth-flap”) choice either, I’ve noticed them saying it even when a character is facing away, and their mouth isn’t visible, so it’s not that.

I admit that I do like the choice, since Jun’ichirou is the same age as Atsushi—who also gets referred to by his first name by the rest of the ADA. It follows the trend of calling anyone 18 and under by their first names, too, since this also applies to Kenji and Kyouka.

It may be a small change, but it’s a consistent one, so it had to have been a conscious choice.

#localization is such a fascinating process to me#i wanna pick the brains of all the members of the dubbing team like a linguistic ryan seacrest#bsdrewatch2023#bungou stray dogs#bsd#jun’ichirou tanizaki#junichirou tanizaki#tanizaki junichirou#tanizaki jun’ichirou#jun’ichirō tanizaki#tanizaki jun’ichirō#i typically watch anime in both japanese & english#it just depends on my mood. or when i started the series#or even based off of how fast the cast speaks (as some shows just have too many people talking at once)#so english dub is sometimes my default for a first-watch#naomi tanizaki#tanizaki naomi#atsushi nakajima#nakajima atsushi#kyouka izumi#izumi kyouka#tanizaki siblings#dubbing#english dub#bsd rewatch#bungo stray dogs#bungou gay dogs#neo queen serenity's posts#junichiro tanizaki#tanizaki junichiro

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey language community - I have a question for y’all

You know how whenever you learn Korean or Japanese, the first warnings you get are “People don’t speak like they do in Dramas/Anime!!”

Can you think of examples of media in your language that are like this? Things that just wouldn’t be used in normal conversations but make sense in that media? Kind of curious!

(I’d especially like to hear about English, as an English speaker, haha. English learners, are there types of media you’re warned not to copy too closely??)

#I’m thinking maybe those really dramatic telenovelas could apply#for Spanish#but English?#the only thing I can think of is kids cartoons#specifically how they say shit like <mathematical!> in adventure time#but I don’t think it’s super common for cartoon to be like that#I don’t think#idk someone help me out please#langblr#language#linguistics#learning Japanese#kdramas#learning korean#Korean langblr#japanese langblr#anime#jdrama#learn Japanese with anime#learn Japanese#my posts

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to learn japanese so bad but idk where to start or if it’ll be worth it in the long run

my dad and i want to go to japan but we don’t wanna turn up to a country where we don’t speak a single word of the language, and i’m also into anime etc and we’re both into jdm japanese cars, we just want to speak the language! but i’m so nervous because there’s like 3 dialects/writing types(?) in japan alone (hiragana, kanji and katakana??) which is very intimidating as a beginner

if anyone has any tips it would be highly appreciated by both my dad and i <3

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

found a kirby fanmanga series that does a very deep dive into the lore of forgotten land and im inhaling it all. also all the waddle dees are so so so autistic

#linked in source#its all japanese. as always. sowwy </3#sphere.txt#LOVEEEEEEEE the characterizations in this one. intelligence (read 'autism') is off the charts#the handling of language is very very interesting too#im as big of a fan of cute wanya wanya poyo poyo silly whimsical kirby characters as the next person#but it just really gets me when like. for example#magolor asks kirby about the implications of giving the animals the concept of civilization (government trade infrastructure etc)#and warns that history will repeat itself. to which kirby gives an equally intelligent but also very trusting answer#like YESSSS TALK MORE ABOUT PHILOSOPHY. LINGUISTICS. ENGINEERING. FOLKLORE <-those are all in the series btw#its such a combo hit for me i love it#also their interpretation of the differences in kinds of magic that magolor (魔術) and marx (魔法) use is so cool....#inserts directly into brain#also also!!!! suzie (susie?? i forgor) characterization is so on point

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

「人」と「者」の違いは何ですか?

what’s the difference between 人 and 者?

they both mean ‘person’ or ‘people’, right?

yes. they’re also both suffixes, and are appropriate in formal and casual settings. but there are subtle differences in their usage.

はじめに、その授業の語彙リスト:

first, some vocabulary:

人前 〖 ひとまえ・h'tomàe 〗 in front of people, publicly.

一人の〜 〖 ひとりの〜・h'tori no ~ 〗 one person, as a counter.

(二人、三人、四人、など1 follow an older japanese numbering system and often bear unexpected pronunciations.)

技術 〖 ぎじゅつ・gijúts’ 〗 skill, technique, engineering.

なくなる 〖 無くなる 〗 to go missing, disappear, run out, be used up.

嘘つき 〖 ぎじゅつ・usòts'ki 〗 liar, speaker of untruths.

利用 〖 りよう(する)〗 use, application; to use, profit from, take advantage of.

恨みを買う 〖 うらみをかう 〗 to incur wrath, envy, or resentment. literally means 'to buy a grudge’. i heart this expression so much.

露知らず 〖 つゆしらず 〗 to be utterly ignorant, (blissfully) unaware.

人 can be used just like any other 普通名詞2。

あれから人前で見せる事が少なかったんだ。唯一の技術に自信がなくなって…

since then3, i've rarely shown them4 in public. my confidence in the only skill i’ve got has run dry…

あの人は嘘つきだ。あの人は僕を利用しようとしてるだけだよ…

that person is a liar. that person has only ever tried to use me to his advantage.

ここに1人の超能力者がいる。

there is one person with supernatural abilities here.

者, on the other hand, pretty much always needs a qualifier.

it’s usually a suffix, related to professions or used to describe qualities of people. you won’t find it in an adverbial sense either.

some words with しゃ・もの baked in:

医者 〖 いしゃ 〗 doctor.

偽者 〖 にせもの 〗 imposter, pretender.

信者 〖 しんじゃ 〗 believer(s), faithful.

死者 〖 ししゃ 〗 dead person/people; casualties.

若者 〖 わかもの 〗 young person/people; the youth.

学者 〖 がくしゃ・gak'sha 〗 scholar.

超能力者 〖 ちょうのうりょくしゃ・chounouryok'sha 〗 person with ESP.

here’s an example with a whole sentence modifying it. 者 functions here much like 事 and 物, with the added feature that it lends completion to sentences in formal writing on its own:

これは恨みを買って来たくらいなどを露知らず者。

this is a person who has not the faintest sense of just how much resentment he has managed to bring down upon his head.

usually read ふたり、みたり、よにん… など means et cetera, and so on, and the like... ↩︎

ふつうめいし。the rough equivalent of nouns in japanese. ↩︎

the speaker first noting that his crush seems more interested in athletic boys. he is anything but. ↩︎

his psychic abilities. ↩︎

#langblr#japanese language#japanese langblr#linguistics#japanese#language learning#studyblr#日本語#usage notes#mob psycho 100#mp100#mp100 manga#learning from anime#anime / manga#manga interpretation#manga#manga raw#mp100 spoilers#文法#文法の基本#自分の文書

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

[MASTERPOST] My Hero Academia Spoilers/Manga Translations Part 1

I try to give the most literal translations possible and add contextual notes afterward in order for everyone to be able to compare the official and other fan translations. My work is not official and is meant to be treated as supplementary notes, like the translation and context notes you get in Shakespeare plays. These notes are for educational and discussion purposes only. Please bear that in mind.

Click here for the full meta index of MHA linguistic analyses and deep dives.

Spoilers Translations:

Ch. 421

Ch. 420

Ch. 419

Ch. 418

Ch. 417

Ch. 416

Ch. 415

Ch. 414

Ch. 413

Ch. 412

Ch. 411

Ch. 410

Ch. 409

Ch. 408

Ch. 407

Ch. 406

Ch. 405

Ch. 404

Ch. 403

Ch. 402

Ch. 401

Ch. 400

Ch. 399

Ch. 398

Ch. 397

Ch. 396

Ch. 395

Ch. 394

Ch. 393 (mature content filter)

Ch. 393 (no images)

Ch. 392

Ch. 391

Ch. 390

Ch. 389

Ch. 388

Ch. 387

Ch. 386

Ch. 385

Ch. 384

Ch. 383

Ch. 382

Ch. 381

Ch. 380

Ch. 379

Ch. 378

Ch. 377

Ch. 376

Ch. 375

Ch. 374

Ch. 373

Ch. 372

Ch. 371

Ch. 370

Ch. 369

Ch. 368

Ch. 367

Ch. 366

Ch. 365

Ch. 364

Ch. 363

Ch. 362

Ch. 361

Ch. 360

Part 2

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

love that my college degrees in Linguistics and Japanese Lang and Culture are solely powering my Tumblr blog while my degree in Archaeology powers my actual career. Worth it. Divide and conquer, boys.

#this is just me rambling#i knew from the start linguistics was not going to be the breadwinner#but i’m glad that it’s major contributions are mp100 metas and translations#truly more meaningful than any desk job#if anyone says they’re not learning japanese for anime or manga at all they’re lying#you gotta embrace it to unlock the full power#you gotta cry your way through historical linguistics and ancient icelandic to make it in the japanese tumblr world#rite of passage#ANYWAY let this be a lesson to everyone: if your university offers you the chance to do multiple degrees at once on a normal grad schedule#say yes#always#it’s more payoff than it is extra work

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haikyuu Characters' Informal & Formal Speech

Something I find interesting about different languages and cultures regarding sociolinguistics is the entire idea of formality. Of course, there are ways to sound more formal/polite in English and ways to sound more informal/rude depending on word choice (synonyms). But with a language such as Japanese, it's the grammatical structure itself (verb endings, vocab) that changes to convey varying levels of formality.

An example would be:

大丈夫? (informal) vs 大丈夫ですか?(formal) = Are you ok?

daijoubu vs daijoubudesuka

これは本だ (informal) vs これは本です (formal) = This is a book.

korewahonda vs korewahondesu

In a school setting, the younger grades (kohai) will use formal speech with the older grades (senpai) as well as teachers: meaning 1st years will be formal to 2nd and 3rd years, 2nd years will be informal to 1st years but formal to 3rd years, and 3rd years can be informal to both 1st and 2nd years.

This is easily shown in basically any anime but this post will focus on Haikyuu since it's the one I'm most familiar with.

Karasuno: Kageyama and Tsukishima definitely hold a very high level of politeness towards their senpai as they always speak formally towards them and also always call them "full surname-san" (Azumane-san instead of Asahi-san, Sugawara-san instead of Suga-san, Sawamura-san instead of Daichi-san, Nishinoya-san instead of Noya-san). It makes sense for them since in general their personalities are quite strict and rigid. Hinata also speaks formally to his senpai but calls them by their more usual names (Daichi-san, Suga-san, etc) and he tends to forget to speak formally out of sheer excitement (not because he's trying to be rude) so he ends up adding on the formal desu copula to quickly change his informal sentence to be formal at the last second. You might think that Tanaka and Nishinoya are pretty relaxed when it comes to formalities due to their crasser personalities but I would actually say it's more the opposite. They're both characters that really like upholding the entire senpai-kohai relationship and it shows in that they are always respectful to the 3rd years and use formal speech (it's also shown in how they both loveee being called senpai and specifically Nishinoya's relationship with Asahi). They still call the 3rd years by their more common names so they aren't as rigid as Tsukki and Kageyama when it comes to names though. The scenes in season 1 when Noya and Asahi were fighting (specifically the storage room fight) were surprising in particular due to Noya changing to informal speech while arguing with Asahi (his senpai).

some other random formalities I've noticed in the other characters: as mentioned in the anime, Kenma doesn't like any of that hierarchy stuff which is why Hinata is able to continue comfortably speaking informally to him even though Kenma is a senpai. The shock and immediate apology of Hinata when he finds out Kenma is older than him is sensible in the cultural context since there are many people who would get quite offended and angry if a kohai were to be speaking informally towards them. Although Kenma is never shown directly talking to any 3rd years (other than Kuroo, which he speaks informally to since they're childhood friends), I assume he would still speak formally since even though he doesn't find formal speech necessary he would still be aware that others would care about it. When it comes to Mad Dog, a small part of me expected him to be completely informal to everyone since those kind of characters are usually like that in anime but he still keeps a pretty formal tone when talking to his senpais which pleasantly surprised me. As far as I remember watching season 4, I don't think the Miya twins use formal speech when talking to Aran. They don't call him Aran-san or anything either, just Aran-kun, which could be another example of childhood friends not needing formalities even with the age gap.

EDIT: i just remembered that Kageyama is so damn polite that he doesn't even differentiate between the Miya twins by their first names, he calls them both "Miya-san"!

If anybody wants a particular character/school to be discussed in detail then just send me an ask and I'll try!

side note: this post isn't proofread so if theres any mistakes or corrections in the info please tell me (✿◠‿◠)

#haikyuu#karasuno#tsukishima kei#kageyama tobio#hinata shoyo#kozume kenma#kenma#kuroo tetsurou#miya twins#miya osamu#miya atsumu#nishinoya yuu#noya#sawamura daichi#sugawara koushi#asahi azumane#tanaka ryuunosuke#japanese linguistics#japaneselanguage#anime#anime and manga

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Japanese language is one of the most indirect languages in the world. There are the obvious examples of this, such as when some customers try to enter a busy restaurant without a reservation and the staff say 難しいですね (”this is tricky…”) instead of simply telling them that there are no seats. However, I've noticed that Japanese’s indirectness may go much deeper than simple euphemism.

Japanese seems to come built-in with ways of avoiding directly addressing your conversation partner.

The Japanese way of expressing things often involves voicing your internal monologue, which means people will say things ostensibly to themselves, even though what they really want is to communicate to the other person. When I first noticed it, I thought it was a bit similar to how some (western) cartoons occasionally handle exposition by having a character mutter something to themselves so that the audience can hear. This can be seen in the following extremely common forms of expression:

Using adjectives as an exclamation

うま!Literal translation: “Delicious!” Semantic translation: “Wow, this is really good”

怖い!Literal translation: “Scary!” Semantic translation: “I’m scared!” or “This place is giving me the creeps”

It could be argued that these single word exclamations may not always be “talking to yourself”. But imo more often than not, they are spoken with the vibe of “I felt this adjective so strongly that the word just slipped straight through my internal monologue and out of my mouth”.

Wondering aloud (かな)

雨降るかな? Literal translation: “Hmm, will it rain or not?” Semantic translation: “I wonder if it’s gonna rain.”

今夜来るかな? Literal translation: “Hmm, will [they] come tonight or not?” Semantic translation: “I wonder if they’ll come tonight.”

Compared to the adjective examples, this is less ambiguous. There’s no direct translation for the verb “to wonder” in Japanese - you just wonder aloud! The literal translations sound funny because they only make sense if the speaker is talking to themself.

Explaining stuff to yourself (んだ)

あそこにあったんだ!(context: the listener has just shown the speaker something they were looking for) Literal translation: “There it is!” Semantic translation: “There it is!”

In this example, the literal and semantic translations are the same, because this is a case of talking to yourself in English! If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense to say “there it is” when the person you’re talking to clearly already knows that’s where “it” is. Instead, the phrase serves to convey satisfaction and surprise.

まだ20歳なんだ!(context: the speaker has just found out from the listener that a friend of theirs is younger than they expected) Literal translation: “[She’s] only 20!” Semantic translation: “She’s only 20? That explains so much!”

In this example, んだ is used to mark the sentence as an explanation of something. The listener already knew the friend was only 20, so the aim of the sentence is not to convey new information, it’s to show that some sort of internal reasoning is happening within the speaker’s mind.

In the immortal words of Carly Rae Jepsen:

🎶 Do you talk to me, when you're talking to yourself? 🎶

For every Japanese speaker, the answer is yes!

#this also seems to be a reason why anime translations sound distinctively anime-like#because the times when someone will say something in japanese is different to when someone would say something in english#so no matter how clever you are with the translation#its always gonna sound awkward or at least very japanese#linguistics#langblr#learn japanese#japanese#japanese language#language acquisition#language learning#日本語#japanese grammar#language#languages#jimmy blogthong

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, this is something that’s been bothering me for a while and I want to talk about it a little bit: I dislike how Japanese terms like “senpai”, “onii-chan” or “onee-chan” got memeified, especially to a weirdly sexual degree. Because like, those terms are not inherently sexual nor do they have the romantic or obsessive implications that people in the west attach to them. “Senpai” is an honorific used to refer to someone who’s either in a higher grade than you in school, or a coworker who’s been working at the place longer than you (so it can be an age thing but mostly it has to do with experience). “Onii/onee-san”, while not an honorific, do literally just mean “older brother/sister” and the reason anime characters use the term so much is because in Japanese, the younger sibling is expected to refer to their older siblings that way rather than use their actual names (whereas older siblings don’t have to do that). It can also be a way of referring to someone who's older than you, since Japanese, like many other languages, applies names for family members to people of certain ages (calling an old man "grandpa" is fairly common for example, and actually considered respectful rather than rude like it is in English).

I’m aware that those words are sometimes fetishized within the anime/manga itself, but that’s not the case every time so for that to be the first thing that comes to peoples minds just rubs me the wrong way. Like imagine if a Japanese person heard the English word “step-sister” and immediately thought of porn. That’s what y’all look like.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Cour" is not a real word, please stop.

#anime#i'm not even sure how it would be pronounced because if anything it would be an english word#english anime fans saw it used somewhere as a bastardization of some other word#(as happens sometimes in japanese)#and they thought they were being so clever by using this insider term#linguistically i guess you might pronounce it “coo-er” like the beer maybe#but also the problem is that context matters and the context is that this term only exists on myanimelist#ergo#it is not a real word#i'm not intending to be a gatekeeping linguist here#i'm not saying “ONLY WEBSTER THEMSELVES ARE ALLOWED TO CREATE WORDS”#but i do feel we need to be intentional and inclusive with new word creation#and this term is in itself gatekeeping#it is not common jargon used widely within an industry#it has a definition that is unclear to the general public and is only meaningful to an exclusive subset of a community#so once more#i argue it is not a word#that said#go ahead and use it if you want#you can keep trying to make it a word#i don't think it'll work but language will die if we don't keep trying to evolve it#also if you think i'm wrong please do let me know#i welcome the argument#like and subscribe

0 notes