#once they embraced the gritty aspect of his character

Text

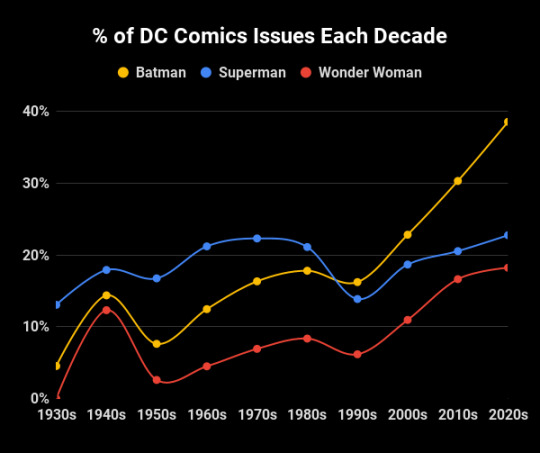

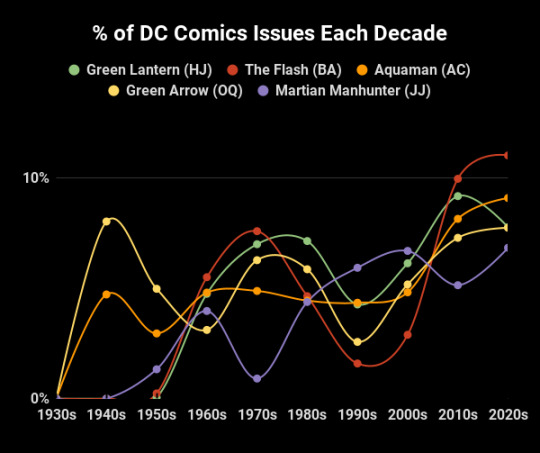

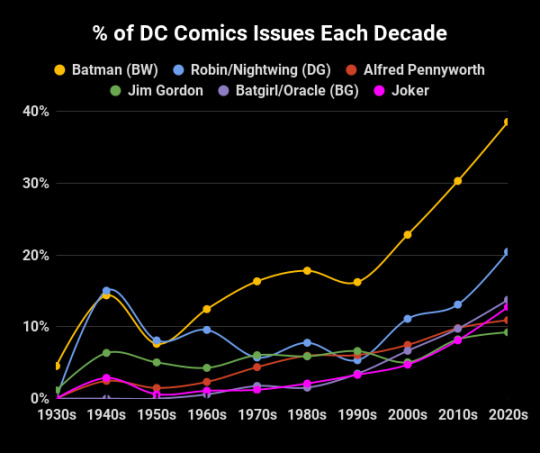

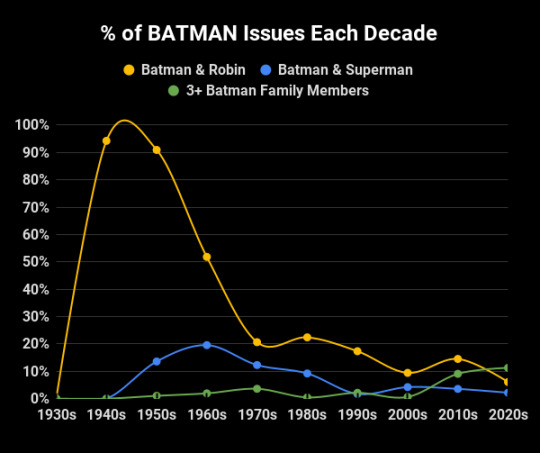

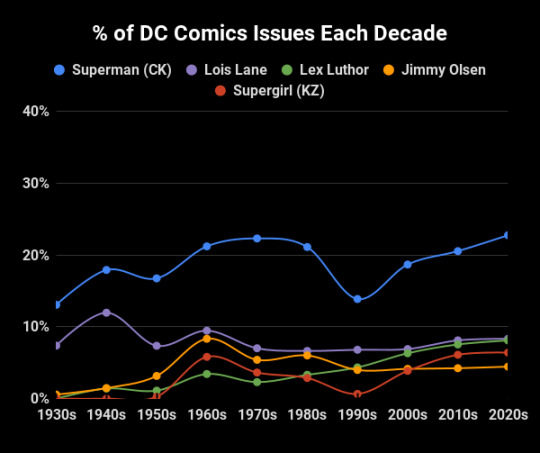

In case it seems like every third comic has Batman in it... you're not wrong. He's been in 38.6% of DC issues since 2020, with a stark increase of 8% each decade since the 90s and surpassing Superman in popularity. Despite this, there's been a massive drop off of comics where he is teamed up with Superman or a Robin (although the amount of group team ups between Batman Family members has increased, as well as Nightwing solos).

#I made the graphs but the numbers were sourced from ComicVine#idk thought this was interesting#once they embraced the gritty aspect of his character#it popped off#but before than it was really just superman who thrived in the absurd space comics#dc comics#my art#batman#bruce wayne#superman#clark kent#wonder woman#lois lane#diana prince#my graphs#dick grayson#hal jordan#green lantern#barry allen#aquaman#green arrow#martian manhunter#barbara gordon#jim gordon#joker#jimmy olsen#supergirl#long post#like obvs not this installment but later ones get long so I'll tag it here to help filter

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

3, 4, 8, 10

103. Favourite character from Prequals?

Anakin Skywalker!!!! That’s my son and I love him ❤️ The story of Star Wars revolves around him and he’s one of the most fleshed out, complex and fascinating characters in Star Wars. His importance to the franchise is highly important and without him the saga would not be the same. This isn’t to say others aren’t important because there are many important characters, but Anakin is one of the most important in-universe and the saga as a whole.

4. Favourite character from original trilogy?

Luke Skywalker. The face of Star Wars and the main catalyst of the Skywalker saga. I genuinely love how Luke didn’t opt to kill his father, his own flesh and blood and instead wanted to believe in him because he knew there was goodness in him, that there was a light sparkling inside of him even when Anakin himself believed it to be gone forever. Luke’s not a typical male hero for his era and I love every bit of it. He chose compassion, forgiveness and love over revenge, violence and hatred, which at the time (’70s and ‘80s) was the common go-to for most film/TV heroes, but Luke was different from them and that’s why I believe he stands out from the rest of the heroes from his time and why he’s still so memorable and iconic after our first introduction to him 44 years ago.

8. Weapon of choice?

Lightsaber :P I like elegants weapons for a more civilized age, I guess ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

10. Which character do you feel is most like you?

Oh lawd LOL

I think I’d have to go with Anakin (hear me out lol). I relate to him in the sense that he and I are very awkward, and I do mean very awkward people. If I met Padmé after a decade of not seeing her and looking beautiful like that, to be frank I would have responded with something similar to what said or even worse lmao. Another aspect of him I relate with is the insecurity. I know it’s commonly said that Anakin was a very arrogant person, but I think that “arrogance” came out of him trying to prove himself to the Jedi because he believed they understimated his abilities, thus making him a very insecure person once you get to the nitty gritty of his character. In a lot of way I’m a very insecure person as well and sometimes I really try so hard to make myself more than I am but deep inside I actually have a lot of insecurities about myself because I see others doing better than I do and I wish I could do the things they do. Did I explain myself well? Others things about Anakin that I relate to is loving Padmé and doing anything for her (if she existed I’d do anything she told me ngl), being extra™, more dramatic than we should be and loyal to those we love. Honestly, Anakin is one of the most relatable and realistic characters in Star Wars, which is why I believe a lot of people didn’t embrace him as much cuz I guess he just hit too close to home for many, although they didn’t want to admit it, but that’s just my theory so take it with a grain of salt.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't cover yourself with thistle and weeds

CW's for this chapter: minor character death, semi-graphic descriptions of injuries, parental death, unsympathetic Remus

Relationship: romantic logince

This prompt was suggested to me by the lovely MizzMarvel on ao3

Chapter title is from thistle and weeds by Mumford and sons

This is Logan’s backstory in my superhero AU. You can find the whole thing on ao3 here or on the masterlist here

As Logan walked home that morning, he felt invincible, untouchable. All the grey days at school fell away, all the teasing and bullying and all the fear was suddenly gone.

He felt like he was soaring, floating somewhere high above his life. He was so much more than himself in that moment.

Maybe, he didn’t want this to end. However terrifying chasing after criminals was, that particular high almost made the danger worth it. He mourned the fact that it would be over soon. That they would put the gang away, file away the info they had collected and go back to school, alone in the knowledge of what they had done.

The ecstatic feeling faded when he entered his garden and noticed the front door was open. His blood ran cold.

Logan dropped his bag to the floor, frustration written in the lines of his posture.

“Hey sweetheart, how was your day?” His mother called from her office.

“It was uneventful as always and I am not in the mood to discuss it further.” He replied shortly.

His mother rounded the corner and took in his drawn face and the force with which he set his books down on the table.

She held out her arms invitingly and Logan let himself be wrapped up in her embrace, savouring the feeling of safety it gave him.

“Are the other kids giving you trouble again?” She asked.

The other kids were the least of his worries, currently. He could handle their childish taunting. His other problems were related to the more dangerous, night time aspect of his life. But he couldn’t exactly burden his mother with that.

She would worry too much and while he wouldn’t exactly blame her for that, he didn’t need her nagging atop all his worries about Roman and Remus.

So he just nodded and left it at that.

His mother didn’t pressure him to say more. She understood that he didn’t always feel like talking.

Once he was finished with his homework, he locked the door to his room and grabbed the locked box he kept hidden away at the back of his dresser. He opened it and carefully arranged the papers inside into orderly stacks.

The box contained a wealth of information, information that could likely get him in serious trouble if it got into the wrong hands. These files were the fruit of months of research and careful surveillance.

Supply routes, lists of buyers, lists of couriers, the entire ledger, even the names of the most elusive members.

This information could dismantle the entire gang and that was their goal. A few more weeks and they had all the evidence they needed.

Public scandals that would knock the leaders off their thrones, accounts of crimes and evidence so solid no judge would be able to refute it.

They would just have to drop it off at the police station and the gang’s fate would be sealed. It made Logan feel a little better whenever he looked at it. Despite the dangers, they were doing something good, something that would make this shithole of a city just a tiny bit more liveable. And hopefully, would help Remus.

Logan had to admit, he didn’t have that much faith in Roman’s plan. In theory, rolling up the drug rink so Remus lost his debts and could leave without fear of repercussions made sense.

But that theory was heavily relying on the fact that Remus even wanted to leave. He seemed way too comfortable in the criminal environment than Logan cared to see.

His phone started ringing and Logan picked it up without looking away from the supply route he was copying onto another paper.

“Hey erlenmeyer trash, you ready for tonight?”

Logan sighed at the nickname.

“Hello Roman, I told you at school I have everything prepared for tonight. I don’t see why you felt the need to call.”

“It’s just...something feels off. I’m scared something’s gonna go wrong.”

“Did something happen to make you feel like this?”

“No, not really. Well, I haven’t seen Remus in a while and he was acting weird the last time I called.”

“Remus dropping off the map or acting strange is not usually a cause for concern. He is prone to doing things like that.”

“Yeah, I know. I just…” Roman sounded uncharacteristically quiet. He must really be nervous.

“Is there anything else that caused this concern?”

“No…”

“Then we will be alright. We know what we do is dangerous, but there are no signs the gang is aware of what we are doing. We have gone undetected for months, it is improbable they would suddenly know now and not give us any sort of indication. But, if you really are worried, we can call tonight off.”

“No! No, the sooner we get this done, the better. And if you say we’ll be alright, I believe you.”

“So you’re listening to me for once. How novel.”

“Yeah, well, don’t get used to it, specs.”

Logan rolled his eyes.

“Just don’t forget the flashlights this time.”

“You’ll bring back up ones anyways. I don’t see why I bother.”

“It’s important to be prepared, definitely if you’re trying to fight crime with someone as scatterbrained as you.”

“You sound like Batman.”

“Good, that’s what I’m going for.”

“Well, caped crusader, I gotta go make dinner. See you tonight.”

“Yes. Don’t forget your scaly panties, robin.”

Roman signed off with a snort and Logan continued looking through the documents. But Roman’s words kept running through his head and his feeling of unease grew. Maybe it would be better to call it off for tonight.

No, Roman was right, they had to get this done as soon as possible. The longer they waited, the more time the gang had to discover what they were doing.

He decided to head downstairs. He had done all his prep work for tonight and sitting in his room feeling anxious wasn’t helping anyone.

Downstairs, music was playing and his mom and dad stood in the kitchen. They held each other close and were sloppily slowing along to the music, horribly off beat.

His dad noticed him standing in the door opening and beckoned him over.

They took him up in their embrace and his dad kept trying to dance, even though Logan was tripping over his own feet and his mother was laughing too much to follow along.

“Logan! Don’t tell me you don’t know how to slow.” His dad exclaimed as Logan bumped awkwardly into his mother again.

“It’s not like I’ve ever done it before. Nobody slows anymore, dad.”

“What a disgrace. My son should at least know how to slow. What if a pretty boy asks you to dance?”

Logan rolled his eyes but his dad was not to be dissuaded and grabbed him.

“Just follow along to the music.” He instructed.

They ran through the steps slowly and after a while, Logan felt himself loosen up a little. His steps became less mechanical and more like an actual dance.

He smiled as he imagined himself dancing like this with Roman, the other boy was sure to enjoy it, always one for outdated romantic gestures.

His mom laughed and then grabbed his father.

“As important as teaching our son outdated school dances is, I still need your help with dinner.”

They finished making dinner together while Logan set the table.

“ Lettuce eat.” His dad called as he set a bowl of salad down on the table and Logan groaned and hid his head in his hands.

“That pun was souper bad.” His mom groaned.

“Stop.” Logan whined.

“What, don’t you loaf my jokes?” His dad asked.

“They’re terrible.”

“I think they’re sub lime. ” His mom laughed.

Logan lay in his bed, the light from his phone lighting up his face as he waited for his parents to go to bed.

Finally Logan deemed it safe enough to leave and he slunk out of the house.

He walked through the silent neighbourhood till he reached the busier, less ideal parts of town.

There, he found Roman leaning against a wall, in a red leather jacket and heavy black boots, blending in with the crowd of people out on a friday night. Logan felt his heart stutter at the careless way Roman was slumped against the wall, his face cast in stark shadows by the neon lights from a nearby club.

He reminded Logan of the devil, of the incarnation of pride, everything about him inviting yet dangerous.

Logan stopped staring and walked over to join him, trying to lean against the wall with the same graceful abandon but only managing to look like an awkward stick.

“Hello, my dark night.” Roman said.

“You forgot the panties.”

“Oh no, what a tragedy. Guess I can’t be your Robin tonight. Maybe I can be your batwoman?”

“Batwoman’s gay, you dolt.”

“I mean, same.”

“And they’re cousins.”

“Yeah, nevermind.”

“Come on, we have a job to do.” Logan reminded him.

They stayed out all night. Skulking in the shadows and trailing couriers all over the city. Logan felt a strange thrill every time he looked over at Roman. His eyes glinted with excitement and adrenaline.

During the day, they were just teenagers, being pushed and shoved and keeping their heads down as they walked to class.

But now, they were so much more. They became a part of the city, let her bustling energy envelop them. They slipped out of their skin under the streetlights and let themselves disappear into the hubbub and danger that prowled the city streets.

They were angels bringing her justice, they were devils tearing her apart.

They hid behind dumpsters in cold alleyways and walked along the busy promenades, holding each other and pretending to get lost in the others touch, all the while keeping their eyes trained on their mission.

Finally, when the sky was turning a murky gray and Logan’s eyes felt gritty with sleep, they ended up on a bench two streets from Logan’s home. In the suburban neighbourhood, nothing was stirring and, even in the city, it was too early for even the earliest risers.

Roman curled up on the bench and stared at him. Logan stared right back, too tired to care about being seen as weird.

“Do you think it’ll work?” Roman asked, his voice breaking the quiet of the park.

“The evidence we have collected is irrefutable, as long as we take care to deliver it to the right people, there is no reason it shouldn’t.”

“Yeah, I know that. I meant Remus. You said he might not come back, even if he is relieved of his debts. What if he’s really just in it because, I don't know, he likes it? Or he just feels like he fits in there?”

“I don’t know your brother as well as you do. If you have faith in him, then I believe it will work.”

“That’s the thing, I don’t know if I have faith in him. He’s just… So different nowadays. It’s like I don’t even know him anymore.”

“Roman, it will be alright. Your brother may have made some mistakes, but it doesn’t mean he is changed forever. Sometimes people just have trouble figuring themselves out. And either way, whether he makes the right choice or not, at least we did our best.”

Roman smiled at him, his mascara smudged and the glow of the street light lighting up his frizzy hair in a halo of golden light.

“You’re a great friend, you know that right?”

“I try my best.” Logan said with a soft smile.

Roman sat up and leant forward. He reached out and gently traced his thumb over Logan’s jaw. Logan looked up into his eyes, his breath stopping somewhere along the path from his lungs to his mouth. Roman’s thumb came to a stop on his lips.

“Is this alright?” He whispered.

Logan just nodded, his usual eloquence rendered mute.

Roman moved in closer and gently, ever so gently, slotted his lips onto Logan’s.

It was soft, and sweet and when he drew back, he pressed his forehead to Logan’s with a bubbly laugh. He threaded his fingers through Logan’s hair.

Finally, after a long moment of his brain incoherently looping the last moment over and over again, he managed to regain some mobility and placed his hand over the one Roman had cupped around his cheek. He turned his head and placed a kiss on Roman’s palm.

“We’re going to change the world.” Roman breathed, ecstatic with sleep deprivation and adrenaline.

“Together.” Logan whispered back.

As Logan walked home that morning, he felt invincible, untouchable. All the grey days at school fell away, all the teasing and bullying and all the fear was suddenly gone.

He felt like he was soaring, floating somewhere high above his life. He was so much more than himself in that moment.

Maybe, he didn’t want this to end. However terrifying chasing after criminals was, that particular high almost made the danger worth it. He mourned the fact that it would be over soon. That they would put the gang away, file away the info they had collected and go back to school, alone in the knowledge of what they had done.

The ecstatic feeling faded when he entered his garden and noticed the front door was open. His blood ran cold.

Had his parents noticed his absence? He had no idea how he would explain this to them.

He entered the house quietly, trepidation burning in his stomach. Should he call out? Maybe he had just left the door open?

But Logan distinctly remembered checking it was locked before leaving.

Downstairs, all was quiet. Everything looked as it should have been except that muddy footprints tracked in from the door to the stairs.

That was disconcerting, there was a very strict ‘no shoes upstairs’ policy in the house.

Logan’s unease grew. He crept upstairs.

“Mom? Dad?” He called out hesitantly.

The house stayed dead quiet.

With a deep breath, he kept moving. He looked in his room first, as it was right next to the stairs.

The door was pulled open. Strange, Logan could swear he had closed it.

His breath hitched when he saw his room. All his drawers were pulled open. His papers were strewn out over the floor.

The box!

Logan found it upturned and shoved in a corner of the room. All the papers were gone. All the evidence they had collected missing.

Ice cold terror clenched around his heart.

They knew.

Without a second thought, he tore out of his room and ran to his parent’s room.

“Mom! Dad!” He choked off when he entered the room.

No! No, no, no, no!

This wasn't real. This was just a nightmare. He would wake up any second. This just couldn't be real.

Blood painted the walls and bedsheets. It looked like a scene from a horror movie, almost comical in its goriness. If he had seen this in a movie he would have scoffed at the overuse of fake blood.

He hesitantly stepped closer and kneeled next to his mother, who was sprawled out on the floor, her entire back a mess of torn flesh and blood and glistening things Logan didn’t want to examine too closely.

“Mom?” His voice came out waveringly.

He reached out. A pulse, he should look for a pulse. He tried to take her arm but recoiled from the blood that covered it.

It was warm and sticky and already seeping through his pants.

“Mom, wake up.” He whispered.

“Mom, I’m sorry. I’m sorry I wasn’t here, I’m sorry I stayed out all night, just please, wake up.” He begged, like apologizing would fix anything.

She still wasn't moving and neither was his dad. Somewhere in the back of his mind, Logan was aware that begging wasn’t doing him any good. He needed to call for help.

But all that came out of his mouth were more pleas.

“Mom! Stop ignoring me! Just wake up!” He yelled and then he started crying, great gasping sobs that tore all the air from his lungs.

He needed them to wake up, he needed to feel their arms around him, needed their comfort. They couldn’t be gone. Not like this, not now, not when just an hour ago, Roman had kissed him, not when outside he could hear the trucks thundering by. This wasn’t real. It just couldn’t be.

He screamed, desperate and heartbroken.

Wake up .

His eyes got caught on a flash of green on the walls and he looked up.

On the wall, painted in a bright neon green, was the symbol he had been studying for months, the gang's symbol, a sword pointed downwards, and underneath it, like an artist’s tag, a sloppy R.

Remus.

Logan felt anger curl in his gut. After everything they had done to help him, this was his answer.

He would pay.

This wasn’t the end. If they thought they could stop him with this, they were wrong. He would get his revenge, he would burn that gang to the ground and he would destroy Remus.

This was personal now.

#sander sides#sanders sides fic#logan sanders#ts logan#roman sanders#ts roman#u!remus#unsympathetic remus#logince#romantic logince#superhero au#ts superhero au#my writing#tell me if i forgot to tag something

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cyberpunk 2077 non-spoiler review

Anyways here’s my writeup about my least favorite parts of 2077 for people who are interested in seeing if it’s for them. Both going to talk about content as well as gameplay. This is for PC version, too, because I know last gen consoles are suffering terribly rn and I wouldn’t recommend the game if you’re not going to be playing on PC. At least not until it’s on sale or the issues have been resolved. It really, really shouldn’t have been released on last gen consoles at all in my opinion - or at least should’ve been released on consoles LATER.

If you like Saints Row, GTA, Mass Effect, Shadowrun, or the Cyberpunk genre in general - I definitely think this is something you might want to take a peek at! I wasn’t anticipating the game until about a month or two before release - so maybe that’s why I’m having a blast - but It’s one of my favorite stories from the past decade as far as sci-fi goes. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it, and It’s really impressed me. I can’t even go into detail about all the things I LOVE because I really want folks to experience it themselves. Just know there’s a very intricately detailed world, all the characters are memorable and insanely well realized and complex, and the story is great fun. Also made me cry like 5 times. It’s become one of my FAVORITE games very quickly.

I’d also recommend Neon Arcade if you want someone who’s been covering the game for quite a while, including the technical and game industry aspect. He does well to go into some detail and even though he’s a fan, I’ve found him to be largely unbiased. I’m not going to go into industry politics here because I feel that’s up for everyone to decide on their own terms.

No spoilers, things to keep in mind, content warnings, etc. below!

CONTENT WARNINGS and issues with plot/story

this setting is dark. very dark. if you struggle stomaching things like dystopian landscapes, body horror, physical, mental and sexual abuse, corporate and gang violence, abuse of children, harsh language, and concepts that mess with the perception of reality - this game might not be for you. It’s a very mature setting, and I don’t mean that in the Adult Swim kind of way. I mean it in the ‘oh shit, it went there’ way. In my opinion I haven’t run across anything in it that was handled distastefully when it dipped into the depressing, but dark and gritty isn’t everyone’s cup of tea and I wanted to give a disclaimer.

The game’s universe in advertising and working for the lower class also exploits sex/sex work quite a bit. This is part of the lore itself because in this universe everyone’s become desensitized to sex and violence to the point that marketing embraces it and makes it ridiculous. I feel it’s very obvious that it doesn’t condone this message and is instead a commentary on consumerism - but people still might be uncomfortable seeing a lot of suggestive stuff all over the place regardless.

Women in game are naked more often than men - even though there is nudity for both. This is likely a mix of appealing to the Gamer Boy demographic (even though the story does NOT actually), or the fact that media is way more cool with seeing naked women than seeing full frontal nudity on men. They probably had to tone some of it down to avoid going above an M rating.

The story is amazing, but sometimes it dumps a lot onto you at once. It’s one of those sci-fi stories that you have to really be following the names, faces, and concepts continually to get it all down. There’s a lot of betrayal, background players, etc. I think by the mid-way point I’d mostly had it, but It’s pretty dense. However it’s still amazing. You might just need two playthroughs before every tiny detail clicks - because there’s a LOT of details.

Honestly I think it would help to read up on the lore first so you’re not going ‘what’ constantly. But people have seemed to manage fine without that also! Neon Arcade has a really nice series of videos (like 2 or 3) that get you up to speed with the universe. It also helps you decide if the tone is right for you.

I think the main story should’ve been longer, also. I don’t mind a 20 hr story, especially in a massive RPG, but It feels like they really struggled to cram as much into that time frame as possible. It skirts the edge of being nice and concise, snappy, and tight - and needing just a few more moments to take a breath and wait a second. This is helped if you do a lot of side quests.

The straight male romance option, River, is INCREDIBLY well written but he doesn’t tie into the main plot in any way whatsoever. It’s very strange and feels like they either ran out of time with him, or slapped together a romance with him at the last second. All the other romances at least know what’s going on with V’s story - meanwhile River has no idea, and you can never tell him. He’s an amazing guy though and I highly recommend his questline. He appears in ACT 2.

In general I’d say not to bother with the romances. There are only 4 total, and while the romancible characters on their own are really well written, the romances themselves are just kinda meh. One romance you don’t even meet until act 3. I don’t think they should’ve been included in the game at all, because they definitely don’t feel as fleshed out as everything else.

CDPR also sometimes forget that women players or gay men exist. Panam and Judy have a lot more content than River and Kerry for example. I don’t think this is intentional, they just have a large fanbase of dudebros. It only shows in the romance content and the nudity thing though.

Johnny, Takemura, and Claire should’ve been romances and I will fight to the death on that.

There are gay and trans characters in the game and their stories don’t revolve around their sexualities. It’s very Fallout: New Vegas in it’s approach to characters: IE. you’re going to love them. All of them.

V’s gender isn’t locked to their body type or their genitals- but to to their voice. I don’t think it’s the best solution they could’ve used but given how the game is heavily voice acted I assume that was what they had to work with.

Some of the romances are locked to both cis voices AND body types (not genitals if I recall but body shapes). That’s disappointing but I assume it was because of scripted scene issues and/or ignorance on the dev’s part considering the LGBT NPCS are so AMAZINGLY done. There’s no homophobic or transphobic language in the game - though there are gendered curse words and insults if that bothers you.

Some characters MAY suffer from ‘bilingual people don’t talk like that’ syndrome. But it can be hard to say for sure given that translators exist in this universe and the way they operate aren’t fully described. It’s only momentarily distracting, not enough to take away from how charming the NPCs are.

The endings are really good don’t get me wrong but I want fix it fic :(. All of the endings out of like 6 (?) in the game are bittersweet.

Both gender V’s are very good but female V’s voice acting is out of this world. If you don’t know what voice to go with/are neutral I’d highly recommend female V. Male V is charming and good but he feels much more monotone compared to female V.

V has their own personality. To some this won’t be a detractor - but a lot of people thought they’d be making absolutely everything from the ground up. V is more of a commander shepard or geralt than a skyrim or d&d pc, if that makes sense. You can customize and influence them to a HUGE degree, some aspects of V will always be the same.

Streetkid is the most boring background - at least for it’s introduction/prologue.

GAMEPLAY/TECHNICAL

If you can run your game on ultra, don’t. It actually looks best with a mix of high and medium settings. Unless you have a beast that has ray-tracing - then by all means use ray tracing and see how absolutely insanely good it looks.

There are color blind modes for the UI, but not for some of the AI/Netrunning segments in cutscenes. Idk how much this will effect folks with colorblindness but those segments are thankfully short.

There was an issue with braindances being an epilepsy trigger because for some reason they decided to mirror the flashing pattern after real epilepsy tests - probably because it ‘looks cool’. I don’t have epilepsy but it even hurt my eyes and gave me a headache. Massive oversight and really goddamn weird. Thankfully this was fixed.

There is no driving AI. Like at all. If you leave your car in the street the traffic is just going to pile up behind it. It’s one of the very few immersion breaking things I’ve encountered.

Sometimes when an NPC is driving with you in the car, they’ll drive on the curb and/or run into people. It’s kind of funny but can occasionally result in something weird. Feels very GTA - but nothing excruciating.

The camera angle feels a little too low in first person mode when driving on cars. You get used to it though.

The police in this game feel slapped on and I hope they improve it. Right now if you commit a crime, you can never tell what will actually trigger it. And if you just run away a few blocks the police forget about it.

Bikes are just way more fun to ride than the cars are.

You CANNOT respec your character after you make them. Ever. it sucks. Go in with an idea ahead of time what you wanna do - it’s better than being a jack of all trades.

as of now you also CANNOT change their appearance after you exit the character creator. This, also, sucks. Make sure you REALLY like your V or you’re gonna be replaying the openings over and over like I did.

Photomode on PC is the N key. Had to look it up. The mode itself is great though

Shooting and Mele fighting feel pretty standard. I don’t have a lot of shooter experience besides Bethesda games so anything feels better than that to me. So far I’ve enjoyed stealth and mele the best, but that’s just my own taste! The combat and driving aren’t groundbreaking by any means, but they’re still very fun. I look forward to running at people with swords or mantis blades, and zipping around the city on a motorcycle to see the sights. The story, lore, and interesting quests and characters are the real draw here.

I haven’t encountered any game breaking bugs in 80-ish hours of play time. One or two T-poses, a few overlays not loading or floating objects - but nothing terrible. Again, my experience is with Bethesda games. This is all usually fixed by either opening your inventory and closing it again, or exiting out and reloading your save.

The C button is mapped for crouching AND skipping dialogue by default. That’s terrible. Change it in the settings to be HOLDING C skips dialogue and you’ll be gucci.

There’s apparently a crafting system. I have never been inclined to touch it. But I also play on easy like a pleb so IDK how it all scales otherwise.

The mirror reflections can be a little bit weird, at least on my end. They always end up a teeny bit grainy despite my computer being able to run everything on Ultra Max. You can still get good screens out of it though!

So many people text me to sell me cars and I want them to stop. Please. also the texting menu is abysmal. The rest is ok tho

It’s pretty clear when you’re going to go into a ‘cutscene’. all cutscenes are rendered in-engine BUT you often will be talking to other characters at a specific angle or setting. The game locks you into this usually by having you sit down. It works for me - after all we do a lot of sitting- but it IS very obvious that it’s a way for the game to get you in the frame it wants to display.

That’s all I can think of rn! If you’re interested but wanted to get a slightly better idea of whats going on, I hope this helps. I’m really enjoying it and despite my issues it’s exceeding my expectations. I’m going to be thinking about and replaying this game for quite a while.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

From your writing asks: #1, 8, 10, 26, and 28 :) I wasn't sure if you had wanted me to answer any specific ones myself, but since it was an ask I wanted to respond properly~

I definitely wanted you to answer some specific ones yourself :^)

What themes would you like to write about that you feel don’t get explored very often?

I think this is obvious to everyone who’s read my more recent fics (so like... my fics from 2016 onwards?), but I like to write “realistically,” especially in regards to joys and pain. When people write about angst things like breakups and depression and physical illnesses they are sometimes hesitant (rightfully or understandably so, in many cases) to really get into the nitty gritty, and in many cases, uglier parts of them, but like, they’re a part of life and people in our lives don’t have a good time (or even many good moments at all) when these kinds of things happen to them. Those moments are still important, though, and I personally feel like embracing the dark aspects of those things makes getting through them in the end more emotionally and existentially powerful? If that makes sense. I’m definitely still wrestling with, like, the extent to which I should write such things (esp. since like, in most cases, fic readers are not reading your fic to suffer), but I think my underlying sentiment as a writer is to examine/meet feelings and life unflinchingly and with some kind of grace.

(I’ll get to the joys eventually. I swear. I have that draft of the second chapter of Lost and Found in my Google Drive. There’s Radiance and the mood in that, too. I just don’t like to write too much preemptive joy.)

The other thing I want to bring up as well is a kind of like... infrastructural realism? Or is it like, socioeconomic, worldly things? Like we’ve talked about this as well RE: how I’m covering Hope in my fics and how you worldbuild a lot around missions and such in yours. I think this is mostly a fic thing since to do this well requires a longer fic with a lot of forethought, and most people don’t have time for that. And honestly most people don’t like Hope for the structural engineering work he put into building new planets either

Favorite dialogue in your wip? (If asked more than once, respond with a new piece each time)

Oh man this interlude is going to be CHOKE FULL of dialogue that will kill me and most of them haven’t even been written yet

But the things that I’ve already put down on my dump file are like all dialogue

Here I just wrote up this thing

Snow: Go on then. Tell me that you don’t miss the stars. Tell me that you are okay with just sitting here day by day, pretending that you don’t know anything, pretending that you don’t have regrets and wants. Tell me that you don’t care if I won’t invite you to the wedding with Serah, if Light finds another man, or if some orphanage is burning on the other side of town. Tell me -

Hope: I don’t think you understand. I never needed anyone to motivate me.

Hope: I needed someone to stop me.

What scene was the most fun to write for you and why?

Hmm... we might have to establish a definition for ‘fun’ :P

I think in more recent memory, I’ve had the most fun writing the dialogue between Hope and E1 in the Intermission, because I relish all opportunities to write him (especially in FWWCH where I’m usually banned from writing in his POV) and writing two of him is just double the fun. I also adore all occasions where introspective idiots have to talk to other versions of themselves because it’s kind of like. The inevitable 404 error when they realize they are actually empathizing with themselves is tearjerker and heartwarming central.

What do you feel like you need to work on as a growing writer? How can you improve?

Oh lordy there are so many things. Lemme just list a few off the top of my head

1) Linguistic ability: There is definitely a part of me that is sad about the fact that leaving my home country at the age of 11 has left me in a place where I am kind of bilingual but kind of... not really “Native” in either. Like, I have this lingering feeling that I’ll never get to the level of a “Native” English speaker/writer, and I definitely hit like language ability walls all the time when I write - things wouldn’t feel naturally lyrical, I’d run out of words, I wouldn’t know how to describe something the way it should be described, the sentence structure variety is pitiful, etc. I think it’s especially apparent when you’re writing a long fic, where like you have to deal with the same things over and over (e.g. writing Hope cooking, or how Lightning physically perceives him, etc) and there’s more of a limit on where natural inspiration can take you. I should read more good prose (since that’s apparently how I get better at English) but, ugh, effort.

2) Characterization: how many times have I whined about how much I suck at writing Lightning lmaooooooo I think the general thing is like, everyone is decent at writing someone they personally relate to, but we struggle when we try to write outside of our comfort zone. Lightning is definitely the poster child of “character unlike me that I’m trying to get a hold of,” but I think I struggled even more trying to write Fang, and I’d probably struggle trying to write someone like Cid seriously. I think a large part of the struggle is trying to morph yourself into that character (or, like, dissociating from yourself and just... “becoming” that character depending on how you view writing meta??) since like, just understanding someone is not enough. Just understanding someone won’t let you write convincing dialogue where they talk and move around the way they usually do. You have to like, become them and that’s really hard when you have a strong writer’s ego (I know, shocking, coming from me.)

3) Worldbuilding: wtf am I even doing with Hope’s White Lotus thing lmaoooooo anyway a world could always be more interesting, consistent, realistic, nuanced etc. And not necessarily through more word count on the worldbuilding-y stuff. I think it’s more about understanding the factors driving the world than anything else. Like what the resources are, who has power/agency, how things are done (e.g., in our world, decisions are mostly made by individual nation states, although large corporate entities often have immense political influence). AND THEN JUST LIKE CHARACTERS THERE’S THE STRUGGLE WITH EXECUTING THEM - like just because I understand there are rich oligarchs behind things doesn’t mean I’m good at writing the Great Gatsby. I dunno, I have a perpetual sense of imposter syndrome when I try to understand and write things about the world, regardless of whether or not the world is real. I feel like a large part of this goes back to the fact that I’m still only in my 20s and haven’t seen much of the ‘real world’ as they say, although I guess I’m technically still way ahead of most fic writers.

4) General writer’s attitude: this influences themes and the heart of one’s writing. When I say that I care a lot about the grace and dignity of my narratives and my characters, it ties back into this - I want to tell human stories, and I want to tell stories that reflect on our struggles and our faith despite said struggles. It’s the kind of lens that I filter all my words through and impacts every word I write. The obvious problem, then, is that my writing’s only ever going to be as perceptive or sympathetic as I am, and that’s something that I can and should always work on. Am I too obsessed with tragedy? Am I honestly far better at posing questions than providing solutions, even when I highly value solutions? How do I become the kind of writer and person that I want to be without driving myself insane or losing touch with the people that I want my writing to speak to?

5) Discipline: Am I ever going to finish FWWCH (or H&L or any of my other WIPs lmao)? Stay tuned.

I think a lot of my self-doubt as a writer comes from just how much I know I can improve on tbh

Do you need background noise to write? If so, what do you listen to?

I wouldn’t say I work with “background noise” - I work with mood-appropriate playlists (did you know I’ve been gratuitously naming all my fic chapters after songs?), or you know, the good ole 2 o’clock cosmic silence. It’s pretty interesting to me actually, since I also have an engineering degree and like... I need silence when I’m trying to logick things like math or the correct wording for a formal writing thing (e.g. a grant or policy proposal). So my creative hemisphere wants stimulation while my mechanical brain wants silence. Figures.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Smile in Sunder City by Luke Arnold Book Review

Jun 26, 2020. By: Drew @ The Tattooed Book Geek

The Last Smile in Sunder City (The Fetch Phillips Archives #1).

Luke Arnold.

352 pages.

Urban Fantasy.

My Rating: Hellyeah Book Review.

Book Blurb.

I’m Fetch Phillips, just like it says on the window. There are three things you should know before you hire me:

1. Sobriety costs extra.

2. My services are confidential.

3. I don’t work for humans.

It’s nothing personal – I’m human myself. But after what happened, it’s not the humans who need my help.

I just want one real case. One chance to do something good. Because it’s my fault the magic is never coming back.

Book Review.

I received a free copy of this book courtesy of the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

There was once magic in the world and magical creatures, dragons, gryphons, elves, werewolves, vampires, gnomes, dwarves, giants, ogres, wizards, gremlins, goblins, banshees, sirens etc. If it is a fantasy creature that you have heard of then the chances are very high that Arnold has included it in The Last Smile in Sunder City and then you had humans, flesh and blood, non-magical and ordinary human beings.

After a devastating event that has come to be known as ‘the Coda‘ where humans who had hoped to harness the power of magic ended up breaking the world. The magic didn’t just cease to exist and leave the world, it also left the magical creatures too making them non-magical and decimating the population. Ageless elves aged, dragons could no longer fly and fell from the skies, unicorns went deranged and, consumed by madness and now run crazed across the land, werewolves got stuck part-way through their transformation leaving them as disfigured monsters, dwarven forges went cold, goblin machinery failed and stopped working and the blood, the sustenance that had sustained the vampires no longer had any effect, it no longer replenished them and they are now, withering. All of the creatures that didn’t outright die when their connection to the magic was severed became ordinary and are slowly fading from the world.

In Sunder City, six years after the Coda Fetch Phillips, a former soldier is now a ‘Man for Hire’ which is a Private Investigator. Fetch receives a phone call from the Principal of the Ridgerock Academy, a cross-species school in Sunder City when a faculty member, Professor Edmund Albert Rye, a three-hundred-year-old vampire goes missing and hasn’t turned up to teach in over a week. Rye is respected and liked, he has even tried to put the old ways behind him and has embraced his new existence in the post-Coda world as best he can and it is entirely out of character for him to no show his lessons. However, when one of Rye’s students, a young siren also goes missing and other vampires are found dead too what was a single disappearance turns into something more with wide-reaching implications.

Sunder City was built on top of a huge underground fire pit. Originally it was a factory mining, smelting iron, making bricks and employed blacksmiths and metal workers and the only citizens were the workers. But, as more and more of the workers decided to stay after their employment ended and over time, it transformed, houses and businesses were built, culture was introduced alongside the production from the factory and it turned into a metropolis. When the Coda hit the fires that Sunder City had been built on were immediately quenched and the city suffered. It is barely hanging on, turning into a slum, many of the residents are destitute, the streets aren’t safe and life there is both dangerous and bleak. Due to the Coda, there is a festering animosity and resentment towards humans. There is still some good left in the city, not much but some, a religious group of winged monks who help the most in need. Devoting their lives to caring for the destitute and the poor. There is bad too, Nail gangs. Roving gangs of humans whose sole intent is to kill the dwindling magical races, erasing them from the world and consuming them to history. That is where the name ‘Nail gang’ comes from as they want to put the final nail in the coffin of the various species, wiping them from existence.

The Last Smile in Sunder City is narrated in the first-person by Fetch Phillips over duel timelines, the past which features a series of flashbacks of important events over the course of Fetch’s life and the present. Fetch is trying to be a better man, trying to redeem himself, atone for his past mistakes and he is taking the first steps on the road to redemption. He is a self-loathing alcoholic who drinks to forget, to numb the pain and who tries and fails to find solace in the bottom of a bottle. His past haunts him, he is full of regrets that weigh heavily upon him, he has made more than a few mistakes during his life, suffered loss and he is drowning in a sea of self-pity, shame and guilt. He hates both himself and humanity and he plies his trade as a Man for Hire solely for the now non-magical races. It is his penance as being a human he is better able to cope with the new world than they are as they attempt to adjust to their new magic-less half-lives.

There is a melancholic charm to Fetch, grit and a dogged determination to him. He has demons but he hasn’t yet fully given into them. He is a terrific main character and narrator, cynical, jaded but wholly likeable. You want to see Fetch solve the case, pull himself up from the brink and redeem himself, not put the past behind him, it is a part of him and always will be but finally come to accept it, that he can’t change the past or erase his mistakes but he can move forward and try to make a difference in the present.

The story is definitely not action-packed, it’s not needed. The few action sequences that are featured add to the overall story which is very character-driven with an additional focus on the world-building. Throughout the course of the story, you learn a lot about Fetch, the magical creatures, Sunder City and the world, in other words, every aspect of the book. It is only a small niggle but, what you learn can feel like information dumping. However, the information is always interesting, adds depth and detail and takes the outline and pencil sketch and transforms it into a full-colour and meticulous picture.

The writing itself is descriptive with some rather unique phrasing and use of words by Arnold giving him his own distinctive and quirky voice.

“His laughter rattled like a sandpaper saxophone”.

To go along with that uniqueness there are also some passages that are laced with meaning and that show a more thoughtful side to the writing.

“You don’t measure age in years, you measure it in lessons learned and repeated mistakes and how hard it is to force a little hope into your heart”.

I’m not the biggest fan of urban fantasy, in fact, it is a genre that I rarely enjoy and that I tend to stay away from. However, I found The Last Smile in Sunder City to be an accomplished and very satisfying debut that I thoroughly enjoyed. It is gritty and grimy fantasy noir and in Fetch Phillips, you have someone to root for who is the beating and damaged tortured heart of the book.

- The Tattooed Book Geek:

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I Read in June

Sorry for the lateness of this one - holidays and other shenanigans got in the way of me finishing this write up. Anyway -

For the Month of June I’ve read Ninth House, Gideon the Ninth, The Last Temptations of Iago Wick, and The Empress of Salt and Fortune.

Ninth House is now my third Leigh Bardugo book. This one is her adult fiction series - and it is reflected in the content. Ninth House is much more harrowing than her young adult titles. Alex is the survivor of a multiple homicide, and no one knows how. She’s tapped to go to Yale on a full ride on account of her ability: Alex can see ghosts. So now she’s plunged into the world of Yale and it’s Secret Societies, where she fulfills the role of accountability for these Secret Societies. In this book, magic is not some beautiful flowing thing. It’s gritty. Characters are up to their elbows in gristle and bones and flesh. It’s gross. Alex’s backstory too, is quite horrifying. The Ghosts she can see are horrifying. It’s a roller coaster of uncomfortable storytelling, but at the same time I was completely hooked - I wanted to know where this story would go desperately. Ninth House is essentially a procedural mystery novel, not necessarily a fantasy like her previous novels, though fantasy elements are present. The plot of the book revolves around several crimes, all of which have to be solved by the end. There is the murder that Alex survived, Darlington’s disappearance, the death of the Bridegroom and his Bride, and the death of Tara. All of these incidents have strings that lead all the way to the end of the book in an explosive end that reveals the truth of it all.

Ultimately, this is probably one of my favorite adult fiction books that I’ve read. Leigh Bardugo is a masterful writer, and I found myself on the edge of my seat with this one, too. Watch out for this one, folks.

Also, a warning - a LOT of content of this book would be considered triggering. Several horrifying things happen, so enter at your own risk.

5/5

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir was the next book I read in June - though I started it in May. Boy, this one was a bit of a slog fest. That is perhaps a fault of my own, and not necessarily that of the author’s or the book’s, though. I’m really not into speculative fiction/science fiction at all - I recently went through my Good Reads shelves and realized that I’ve read less than 10 science fiction novels in my entire life. They just do not appeal to me - and it’s for a reason that Gideon the Ninth falls into as well - the book intentionally obfuscates for about 150 pages - it’s majority of the time an info dump about the technology of the universe that has been crafted for the story. I don’t enjoy that - in fact every time I run into it I can feel my eyes glazing over and boredom setting in. That was largely why I ended up putting it aside to read other books first. Once I came back to it, however, it was still a slog for a bit before the story actually began to pick up.

The story follows Gideon Nav, who is a disgruntled indentured servant of the Ninth House - one of the nine necromantic houses in the galaxy that serve an undying Necro-Lord Emperor. She is forced to become the Prime Cavalier of her house in aid to the Reverend Daughter - Harrowhark Nonagesimus, who is the strongest necromancer the house has ever produced. She and Gideon, however, have a past - they absolutely hate each other. The nine houses of the galaxy have been called to the first house, and all of them are to participate in a contest to see who can become a Lyctor - basically a suped up Necromancer in service to the Emperor. That’s basically the gist of the main plot - there’s also a bit of a murder mystery that takes place because necromancers and cavaliers start dropping like flies, but the core of the story is the interpersonal relationship between Gideon and Harrow. It’s a decent enemies to lovers trope done well - though I would argue they don’t actually become lovers at all - merely come to an understanding about their own pasts. Their relationship can be very much defined as toxic co-dependence.

Ultimately the story was alright - I wasn’t very wow-ed by it, as the world building felt extremely thin, though I did find the necromancy aspect interesting. Gideon and Harrow are both interesting characters on their own, but ultimately the story wasn’t extremely gripping for me. My biggest gripe of it all, however, is that I never found out what exactly the Emperor was fighting against. What is the great threat to the existence of the galaxy that makes Gideon dream to be a part of it, what necessitates the Lyctor trials even being called once more? I never found that out.

3/5

After that I decided to breeze through some smaller books - if they can even be called books at some times.

The next book I tackled was The Last Temptations of Iago Wick - it’s a self published book by Jennifer Rainey, and follows two demons working for Hell in 19th century New England. It has a bit of a steam punk flare, though it’s not hugely present, and is whip crackling funny. It very much reads like a Good Omens alternative universe fanfiction that got tweaked for publication, but honestly, that doesn’t bother me because it’s simply that enjoyable.

Iago is to be promoted into essentially a regional manager in the efforts of Hell against the forces of Heaven. He specializes as a Tempter - creating Faustian Bargains after Bargains with finesse and panache. His partner in his efforts and in his Demonic life is one Dante Lovelace, a “Catastrophe Artist” who specializes in mass mayhem and death. He is described as Byronic and gloomy, with taxidermied animals all over his apartment. Iago and Dante’s relationship is so refreshing - they are queer without fanfare. There is only passing references to period typical homophobia, but their relationship is sweet and presented without drama and trauma.

Iago’s current assignments are to essentially take down the Order of the Scarab - a secret society pulling the strings in Marlowe, who have murdered and bribed and intimidated in order to further their own ends, but a demon hunter stands in his way of accomplishing his goal.

The book has some interesting segments about free will, the nature of Heaven and Hell, which if you know me I’m wont to eat up eagerly. This book was a nice change of pace after the frustrations of Gideon.

4/5

The final book I read for the month was The Empress of Salt and Fortune by Nghi Vo. This is more of a novella than an actual to goodness novel, but it was extremely satisfying and well done. This was the book that made me go “well maybe a book doesn’t have to be 200 pages to convey a proper story.” I don’t want to give too much of this book away, as I feel it is an experience that needs to be truly embraced blindly. It reads much like a kind of flowing, poetic prose, however, and the overarching theme of the novel is primarily that of the vengeance and rage of women against an unjust world. I highly recommend this one as a breeze read, though if you are anything like me it will leave you more than a bit emotionally compromised after.

5/5

For the month of July I have mostly taken a break for the first few weeks, just enjoying some time to myself. I have read the first season of Lore Olympus and that will be included in my July write up, but for July I intend to take some time to decompress and deal with wedding planning. I still hope to read a few books though, and my July list is The Vine Witch by Luanne G. Smith, The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones, and Merchants of Milan by Edale Lane. I actually began The Vine Witch in June but it has not exactly kept me riveted to its pages, so hopefully I can finally slog through it.

See y’all at the end of the month!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Godless review – Netflix's wonderfully wicked western fires on all cylinders ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Jake Nevins - Wednesday 22 November 2017 09.47 EST

Godless, Netflix’s new seven-part miniseries, opens in 1884, in Creede, Colorado, with a thick cloud of smog shrouding the camera. The haze slowly dissolves to reveal a chilling landscape: parched bodies being tended to by swarms of flies; a man, sedentary, with a gunshot through his head; a train-wreck near which a young boy hangs from a noose; and a woman, crouched over a corpse, singing mournfully about Christ. It’s a near-wordless several minutes, a triumph of mood and cinematography, that evokes the sort of rough-and-tumble anarchy of the great filmic frontiersman. Soon after, we’re in La Belle, New Mexico, where we learn who’s responsible for the massacre, and from thereon it’s guns blazing.

Written and directed by Scott Frank and executive-produced by Steven Soderbergh, Godless is grim, exciting and visually arresting. It’s slow, but necessarily so, patiently offering vital exposition while its classic, western plot unfurls itself violently. That violence can be pegged, mostly, to Jeff Daniels’ Frank Griffin, a menacing, one-armed outlaw who’s looking for a man named Roy Goode. Goode, played by Jack O’Connell, was once a member of Griffin’s criminal cabal, but when a train heist turns savage and Goode saves a woman who’s being raped, he bucks town with the loot, staves off Griffin and his 32 men, and lumbers to a farm owned by Alice Fletcher (Michelle Dockery).

Fletcher, who Dockery plays with brutal, soft-spoken gravitas, is twice-widowed and lives with her son, Truckee. After a catastrophic mining accident wiped out most of the townsmen, La Belle has become a colony of tough, strong-willed women, the sort of place one imagines Julie Christie’s Mrs Miller might have resided had McCabe not been in the picture. A bit of internet digging reveals that La Belle was actually a real town, in Taos County, New Mexico, named after Belle Dixon, the wife of a gold miner; though it lasted just 16 years, it makes a weird kind of sense that it’s been revitalized in 2017 as a proto-feminist pasture, shot in a sweeping 2.39:1 aspect ratio where horses roam and women rule. And the show sets itself up for those women to stand their ground against Griffin’s outlaws.

Godless was originally intended to be a movie, but Soderbergh encouraged Frank, who co-wrote the screenplays for the films Logan, Marley & Me, and Minority Report, to turn it into a miniseries. After watching the hour-plus-long first episode, which only plants the seeds of what’s to come, and the equally lengthy ones that follow, it’s no wonder Soderbergh thought the script a better fit for television. Characters are developed richly but steadily, and much needs to be established before Griffin and Goode’s inevitable confrontation, the lead-up to which is beautifully protracted to give weight and import to several other characters, among them Merrit Wever’s Mary Agnes, another of La Belle’s gritty, gun-toting widows, and her brother Sheriff Bill McNue (Scoot McNairy), who is hot on Griffin’s heels and delivers wonderfully hokey one-liners like, “You don’t seem all that much like a desperado so much as you just look desperate.”

It’s hard to pinpoint one standout performance; Dockery is superb, wielding her gun with mighty force, and so is Wever, who’s been a stalwart supporting player on shows like The Walking Dead and Nurse Jackie; Daniels is a convincingly boozy villain, whiskey dribbling down his beard as he looks to exact revenge on his old protege; and McNairy, O’Connor and Thomas Brodie-Sangster, as the town deputy Whitey Winn, each turn in authentic, understated performances. It would not be surprising to see one or two or even three of them in the Emmys conversation next summer, which tends to emphasize plucky, period-piece roles like these.

The plot may be too slow for some – which, in addition to the genre, might drive viewers away – but Godless is worth it if only for aesthetic pleasure. Shot by Steven Meizler, who worked with Soderbergh on The Girlfriend Experience, the long, vivid tracking shots are lyrical and impressionistic, and there’s a scene in a church, where Griffin implores the townspeople to steer clear of Roy Goode lest they suffer like Christ did, that brought to mind the great face-off between Daniel Plainview and Eli Sunday of There Will Be Blood. That the series is so full of cinematic references both visual and narrative is part of the fun; Godless doesn’t resist its classification as a western with a capital W, and instead embraces the genre’s outsize influence in the American film canon.

Godless is now available on Netflix worldwide

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/nov/22/godless-review-netflix-wonderfully-wicked-western-fires-on-all-cylinders

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CINEMATOGRAPHY OSCAR NOMINEES ON AUTHENTICITY AND AVOIDING VFX https://ift.tt/2OZteQ0

The DoPs behind 1917, Joker, The Irishman, Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood and The Lighthouse reflect on the bold choices they made to bring dynamic visions to the screen.

Cinematographers are moving both forward and backward in technological terms this year, ironically in pursuit of the same goal: authenticity.

Avoiding VFX and instead opting to shoot reality has been a central theme. Robert Richardson used real Los Angeles backgrounds for the driving scenes in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood. Roger Deakins contended with real explosions and fires in Sam Mendes’s 1917.

Rigging equipment has also been a common talking point for DoPs in 2019. Deakins pushed the boundaries of stabilising devices to enable extended tracking shots for the continuous-take approach of 1917, while Papamichael explored the limits of large-format cameras, putting them in positions that would have been impossible a few years ago (on a low mounted arm attached to a racing car, in one case). Perhaps most complicated of all was Rodrigo Prieto’s “three-headed monster”, a three-camera set-up used to aid the CGI de-ageing process for Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman.

These and other top cinematographers no longer debate analogue versus digital, with plenty saying it is digital and film, rather than digital or film. This is in part due to rapid advances in camera technology by companies like Arri, with films including 1917 utilising a large-format digital camera that, according to Deakins, is as good as any film camera.

Mixing light sources has also been in vogue, with Lawrence Sher using harsh fluorescents and urban streetlamps to create the heightened eeriness of Joker and grittiness of the city.

Whether they are using old-school filmmaking techniques or the latest technology, these cinematographers are creating brave new worlds for audiences and their craft.

Lawrence Sher - Joker

SOURCE: NIKO TAVERNISE

LAWRENCE SHER ON THE ‘JOKER’ SET

Lawrence Sher has been known primarily for his work on comedies including Todd Phillips’ The Hangover trilogy, Paul, The Dictator and I Love You, Man, before he reunited with Phillips to create the dark, sinister world of Joker.

While Joaquin Phoenix’s performance threw up regular surprises during the shoot, Sher was a ready and willing partner for the award-winning actor, and says his own work plumbing the depths of the DC Comics arch villain — which won him Camerimage’s Golden Frog award in November — is not as big a departure as it initially appears.

What was the shooting schedule like for Joker?I read the script about a year before, did an early scout in March [2018] and then prepped for 10 weeks. The shoot lasted 60 days with one day of shooting lost due to issues with the LED lighting on the New York City subway sequence.

What was your approach to Joker’s colour scheme?My main colour palette was drawn first and foremost from real lighting fixtures that exist in the city. I also looked at movies of that era in which the movie takes place [1981], the colour of the film stock at the time and how it would capture all of this mixed light. The colour palette is a mix of utilitarian light and uncorrected fluorescents — we kept their crappy look so it wouldn’t be clean.

We changed out some of the streetlights so they would be sodium vapour, as opposed to LED which many streetlights are now. When we shot at dusk, you have that blueish light that mixes with the sodium vapours and suddenly you have the colours that I think people associate with the movie: the blues, greens, oranges and greys. You can see the messiness of the city.

How did you approach working with the actors to capture their performances?On set we maintain a certain rhythm for the actors. If they have to go back to trailer, even for 20 minutes, there is a momentum loss. So if I can shoot fast, they never have to leave the set. It helps everybody, especially the scene.

Todd Phillips encouraged improvisation, for instance the bathroom scene where Joker starts to dance after killing the men in the subway. Did that approach affect the shooting?That shot was improvisational. He was going to come into the bathroom, hide the gun, wash off the make-up and stand in the mirror and laugh. But with Todd, the movie is constantly being rewritten so you are discovering it as you make it. All of the planning is there but he’s always flexible. With that scene, he wanted to try it non-verbally. He played a piece of music — he didn’t tell the camera operator what was going to happen — and we got that scene in one take.

Was your approach to Joker different to your other films?My lighting approach is not any different. We are not servicing comedy [in Joker]. Some of the compositions come to the forefront perhaps, more than in my previous works. But my approach, particularly with Todd, is to allow for flexibility and freedom. A lot of it is co-ordination with production design and needing the freedom to be able to light a big space. To have the world lit as opposed to focused on a specific person on a mark.

Which sequence was the most challenging to shoot?The subway scene where he kills three Wall Street guys. We shot on a stage and with LED panels. It was challenging because while we had more money than other independent films, it’s still a budget issue. Todd had always described it as a fever dream — this kind of escalating light show. We accomplished it with a very expensive row of LED lights on both sides, though not too many LEDs because we tried to keep to the light as they had it in the 1970s and ’80s. I was taking the New York subway all the time and shooting with my iPhone to figure out the lighting for that scene.

How did you find working with Joaquin Phoenix?It was a transformative experience watching him act and getting to know him. I didn’t say anything to him during prep; he was a little bit intimidating. He apologised to me for acting weird and I said, “No man, do your thing.” We grew to have a good relationship, where we would challenge each other with the choices on set.

Rodrigo Prieto - The Irishman

SOURCE: NIKO TAVERNISE PICTURES

RODRIGO PRIETO WITH MARTIN SCORSESE ON THE SET OF ‘THE IRISHMAN’

Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto has worked alongside acclaimed directors including Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu (21 Grams, Babel), Ang Lee (Brokeback Mountain) and Pedro Almodovar (Broken Embraces). The Irishman marks his third feature with Martin Scorsese, after The Wolf Of Wall Street and Silence.

Prieto describes the epic crime drama as one of his most challenging projects to date: an intensive 108-day shoot involving more than 300 set-ups, with the added challenge of managing a complicated CGI de-ageing process for the main actors, which incorporated a “three-headed monster” camera rig.

Although Martin Scorsese is an avid supporter of shooting on film, you had to use digital as well to achieve the de-ageing technique.Yes, 56% was shot on digital and 44% on film. The overall look I thought had to be based on film negative because of the memory aspect. Scorsese talked about home movies, this sensation of remembering the past through images, so I developed looks based on still photography, Kodachrome and Ektachrome.

For the visual effects, it was necessary to shoot with digital cameras where the face had to be replaced with CGI. Visual-effects supervisor Pablo Helman from Industrial Light & Magic needed three cameras synched for every angle and the shutters had to all be in perfect sync. The challenge of getting three cameras to move in unison meant that using film cameras from a practical standpoint was nearly impossible.

Was it Pablo Helman who came up with the idea of using CGI to de-age the actors?Yes, when we were shooting Silence, Pablo said he thought there was a way to make actors look younger through computer-generated imagery. He came up with a three-headed rig where the central camera, the Red Helium, is capturing the shot and two witness cameras, Arri Alexa Minis, are sat on either side of the main camera to read the infrared map of the actors’ faces. We called it the “three-headed monster”.

Can you talk about the stages of the de-ageing process and how that was achieved?There are several different stages. Prosthetics were used to make the actors look older. Make-up could make the actors look younger, for example making a 70-year-old actor look like they were in their 50s. VFX and CGI de-ageing were used when the actors are close to the transition to make-up, and that was complicated as the ageing transition was subtle, say, only a few months in time rather than several years. The technical and make-up teams had to be sure the transition was smooth.

How did you map out the visual arc of a film that spans five decades over three-and-a-half hours?We did not want to make it over-stylised or flashy. Scorsese wanted the camera to reflect the way Frank Sheeran [played by Robert De Niro] approached his job, which was simple, methodical and repetitive. The audience sees the same shots with Frank — the camera pans around at the same angle. When we were with other characters, like crazy Joe Gallo, the camera behaves differently.

How did the fact the film was made to screen first and foremost on Netflix affect the way it was shot?For the most part it wasn’t a consideration. Scorsese designs his shots in a way that helps the story. The one thing we did change was the aspect ratio. Normally, Scorsese would use widescreen but in this case we thought we had better use 1.85 because it would fill up home screens. It also fit Frank’s personality more, as well as helping to show the height difference between the characters. Frank was a tall man so we made special shoes for De Niro and boxes with cushions where he sat. For accuracy, we also changed his eye colour to blue.

You were working on a tight schedule. Was there any room for improvisation during the shoot?When the actors want to try something different, Scorsese will almost always go for it. Near the end of the film, Frank is looking as his car is being washed and it’s a defining moment. We lit the scene for him standing and always looking at the car. Then De Niro said, “I always kind of imagined being inside the car.” So Marty said, “Oh, OK, let’s do that.” I had to set it up in three seconds. As soon as we shot it, I could see that his performance was there.

Jarin Blaschke - The Lighthouse

SOURCE: CHRIS REARDON

JARIN BLASCHKE ON THE SET OF ‘THE LIGHTHOUSE’

Born in the Los Angeles suburbs, Jarin Blaschke continues a collaboration with filmmaker Robert Eggers that began on the latter’s 2008 short The Tell-Tale Heart and encompassed his haunting 2015 feature debut The Witch. For The Lighthouse, the pair conjured up another strange and foreboding world: a mysterious New England island in the 1890s, inhabited by lighthouse keepers Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe. Blaschke deployed innovative lighting and lensing solutions to take on not just the wilds of authentic Nova Scotia locations, but the demands of dark, cramped, wet settings.

How many years did it take to develop the concept of The Lighthouse?I didn’t have a script until a month or two before prep, but Rob first pitched this idea probably three years before that. With him, it starts with atmosphere, so my subconscious was working on the atmosphere at the same time that we were developing The Witch. We didn’t know which one would go [first] and then The Witch happened.

The Lighthouse was shot in black and white, with a 1.19:1 aspect ratio, on Kodak Double X 35mm film format, which dates from the 1950s. How much testing did you do?There was a battery of tests I put myself through, like testing real oil lamps to see how to do it with an electrical lamp. I had to know how to light differently: I bolstered the light levels by 15, sometimes 20 times, and the film stock had to be tested in rain, backlit to know where it looks like night but also doesn’t look overly lit.

What logistical challenges did you face shooting on location in Nova Scotia?The weather was bad and added about four days to our schedule. It could have been worse but we had a covered set. We couldn’t do a night scene one night because it was too windy and even with day scenes, you have frames where you need to bounce light back using a giant sail and it gets a little hairy. There was a lot of eating cold porridge in the dark in the morning and the breakfast tent was going to blow away. We had to build this hardcore tent just to have breakfast. It adds to the movie, I hope.

In exploring the space between reality and insanity in The Lighthouse, did you use special lenses for certain scenes?I went to Panavision. I know vintage lenses are really trendy right now. I had some experience with the usual suspects: Cooke Series 2s and Super Baltars [used in The Godfather and The Birds]. They put original Baltars in front of me and I fell in love with them. So we had old Baltars from the 1930s. We used the first high-speed portrait lens of the 19th century for special shots, like [Robert Pattinson] having sex with a mermaid, the hand going down the body. Stuff that was super heightened where we could get away with it.

How did your collaboration with Eggers inspire you for certain images?I’ve known Rob for 12 years so I knew there were going to be a lot of symmetrical two-shots. There is one direct reference to a Sascha Schneider painting. And the last scene in the film is in the lookbook. Those are the only two references, everything else I tried to create. I know Rob watched all kinds of crazy stuff, like videos with shark genitals.

You are also working on Eggers’ next film, The Northman. What can you say about it?Rob says very little. It’s a bigger movie than the others. I can say it’s a Viking revenge movie and we are shooting in Europe. I think he feels a responsibility to do a trilogy. It’s dark and unusually violent.

Robert Richardson - Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood

SOURCE: ANDREW COOPER

ROBERT RICHARDSON WITH QUENTIN TARANTINO

A nine-time Oscar nominee and three-time winner, Robert Richardson’s career has been closely associated with three filmmakers: Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino. For Stone, he photographed 11 features in a little over a decade, winning the Oscar for JFK; two of his five collaborations with Scorsese brought him Oscar statuettes (The Aviator and Hugo); and he shared Camerimage’s director and cinematographer duo award with Tarantino for their work across six films including Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood. Richardson is known across the industry for pushing boundaries and doing whatever it takes to achieve a shot.

How would you typify your relationship with Quentin Tarantino?A relationship with a director is a marriage. I have been fortunate enough to forge a series of relationships with all of the directors I’ve worked with from the beginning. It’s the idea that you are linked together and begin to understand how the other speaks, what you like and don’t like. It’s so important. Collaboration at that level is why rock ‘n’ roll bands are the very best when they hold out and play together as the same team as long as they can. The Beatles wouldn’t have been who they were without John, Paul, George and Ringo.

What is your creative process like with Tarantino once you’ve read the script?Quentin was in the room when I first read the [Once Upon A Time… In Hollywood] script. It took me a substantial time to read it. After we had dinner, we made notes and then he played music: ‘Good Thing’ from Paul Revere & The Raiders, ‘Mrs Robinson’ from Simon & Garfunkel, ‘California Dreamin’ from Jose Feliciano. The soundtrack is like a character in the film; it leads you, it is continuously playing from a radio station. The music helped build on the emotion of the characters and the movement of the film.

What is Tarantino’s process for selecting shots?He only shoots on film, he only processes on film and he only watches dailies on film. He doesn’t see digital replication until he gets to the Avid in the editing room. Our process is to shoot a film chemically, process and print chemically, and that print is duplicated on a 35mm projector. You then project the film as well as the digital intermediate, and they need to replicate each other perfectly, otherwise Quentin doesn’t want to discuss it. It’s definitely challenging, but that’s how we get to be better artists.