#max norman

Text

youtube

Friday, May 3: Ozzy Osbourne, "Now You See It (Now You Don't)"

Although Ozzy Osbourne’s legacy, both in and out of Sabbath, remains unimpeachable, looking back on his solo catalogue reveals just how much of a passenger he was on his own albums: the success or failure of any Ozzy record was almost entirely dependent on the combination of band lineup and producer, and in a lot of ways every last one was every bit as Los Angeles as anything by Van Halen. So while Bark at the Moon was a great record, and Ozzy himself was fully engaged even while completely snowblind, the album’s strengths ultimately lay in the power of Tommy Aldridge’s drumming, Bob Daisley’s steady bass and empathetic lyrics, and Jake E. Lee’s crunching and shredding alongside Daisley and Max Norman’s well-balanced production (Ozzy himself was listed as a co-producer, but come on now). Certainly all of those factors were central to making “Now You See It (Now You Don’t)” an entertaining if somewhat lightweight rocker. Lee’s central riff was hefty but also floated above Daisley and Aldridge’s driving and nimble rhythm section, and if the production was a bit slick, the same could be said for every Ozzy album, even the first couple. To be fair to the Ozzman, he sounded fully present and was in good form vocally, and there was no discounting his charisma and sheer presence. But the true story surrounding this track, along with the rest of Bark at the Moon and every other Ozzy solo record, centered on an especially cracking backing band.

#heavy metal#metal#heavy metal rules#heavy metal music#listen to metal#metal song of the day#metal song#song of the day#song#ozzy#ozzy osbourne#bark at the moon#bob daisley#jake e. lee#tommy aldridge#don airey#max norman#80s music#80s metal#heavy music#heavy rock#metal rock#metal music#listen to music#long live rock#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Max Norman, Nostalgia, and the Slayer Reunion

Who is Max Norman?

Max Norman is an English producer and engineer who has been part of the metal scene since 1973. He produced Ozzy Osbourne’s classic albums, such as Blizzard of Ozz, Diary of a Madman, and Bark at the Moon. He’s produced records from Megadeth, Loudness, Death Angel and Grim Reaper, amongst multiple other artists. He’s also done mixing and engineering for many of the previously…

View On WordPress

#2024#dave lombardo#death angel#emperor#Features#gary holt#grim reaper#ihsahn#jeff hanneman#kerry king#loudness#max norman#megadeth#nostalgia#ozzy osbourne#paul bostaph#slayer#slayer reunion#tom araya

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

a responsibly equivocal stance

Max Norman's review of Diane Arbus's work in The Drift brings together some questions I've wrestled with lately, as I always wrestle with them: the questions of having a position on an artist and having complex assessments of art. Some of this is triggered by the experience of watching some friends of mine process the Oscars and the sweep made by Everything Everywhere All at Once—a therapeutic millennial movie that seems to want to palliate viewers' childhood wounds by using larger-than-life spectacle as a vehicle for overly simplified sentiment, and is being disproportionately rewarded considering its ultimate lameness (the natural product of excessive spectacle for those who don't find that charming) and conservatism. (The case for the conservatism is laid out quite well by Kieran McLean, here.) Versus the kind of artwork that tries to be several things at once, say TAR.

Which everyone online seems to be kind of stupid about? Much of this is likely shaped by Twitter's particular economy of terse opinions, quote tweeting, and dunking. Versus, say, an ecosystem of alt-weeklies or blogs issuing comparatively considered pieces (written by critics of whatever stripe, and not Twitter-posting Substackers, each hanging out their own little shingle, subjected to the demands and incentives and scale of those platforms), which people then reflected on via comments in comment sections—which is not to glamorize blogs or comment sections, just to say that what we've got now might be worse than what we had then. With TAR, it feels like a film that was designed to be ambiguous enough to evoke multiplicity in its interpretations just got such flat reads from people whose tastes I normally trust. It was a portrayal of an abuser in cancel culture being justly punished for her arrogance. Or it was a portrayal of an abuser being unjustly punished, because according to Todd Field, Lydia Tar's genius, or her age and socialization to older mores, or the perceived stupidity of her antagonists in the culture—for all that I don’t think the student she argues with, in a moment that goes viral and begins her fall, Max, is actually meant to be seen as stupid—ought to have excused her bad behavior.

To my mind, the film seemed to want to do both these things—or, as the memes would have it, a secret third thing, some hybrid of the two.

It seemed Field wanted to show a person whose character has been dessicated by the pursuit of fame experiencing the destruction of all her ties to the world that satisfied her desire — perhaps even to get back in touch with some new form of creation both degraded and genuine. Yes, Tar, at the end of the film, is in an objectively worse position than when she began. And she's not exactly saved. She may not be capable of any reckoning with herself more concrete than the atavistic, overwhelming stab of feeling that makes her vomit when she's confronted by a reminder of the women she worked to manipulate, like Krista and Olga, in the form of the girls in the spa she visits, lined up like a banquet for her delectation. She's also conducting in a meaningful way, absorbed in the act of it, in a way she has not been up to that point. And she is so because now, she has no other choice...

All this is to say: maybe Field wanted to create an object that could meaningfully be taken several ways. Maybe he meant us to go back and forth on whether Tar is right or Max is right, or to what degree; maybe he meant us to like Tar in some ways, or to find her charismatic or funny in fucked-up ways, and to disapprove of or hate her in other ways, to find her blinkered and odious and sad in her attempts to aggrandize herself. All this is so very basic to say, and I don't mean to imply I'm being radical here, but I have had this thought: maybe we're fucking up by being so insistent with how we feel about this movie and what we think it's saying About The Culture We're In. Artists shouldn’t be expected to have a single stance on something, a single intention that each work exists just to express. An artist can, should, be working through something...

Which brings me back to the Arbus piece. I appreciate Norman's calling out the position taken by curator John Szarkowski and critic Sebastian Smee that Arbus meant to humanize her subjects. I don't think Arbus's intent was to rehabilitate, to "show," as Szarkowski has it "that all of us—the most ordinary and the most exotic of us—are on closer scrutiny remarkable"; that would be banal, and perhaps as instrumentalizing of the subjects as work made to emphasize their strangeness. "Does Arbus’s photograph ["A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C., 1968"] send him up, or support him?” Norman asks, “Or is the real joke on the viewer who insists on one interpretation or another?" I don't think it's a joke played on the viewer who insists on one interpretation or the other; I do think that viewer ought to be capable of acknowledging multiple possibilities... Maybe—to state another basic point—artists, whether Diane Arbus or Todd Field, don't have answers, but questions, and they chose to do something felt as well as thought to represent them... And I think artists should be allowed to look bad, to have complicated feelings, to encounter a desire to gawk or objectify and portray that desire with a degree of honesty and interrogation so that those of us who, obeying certain limits that collective life justly(!) places, won't cop to it can confront it in some form...

I do want to be clear that interrogating the ethics of Arbus's relationship to her subjects, so many of whom were marginalized as she was not, feels useful and necessary. I also don't think we can do that with much precision if the only question we ask is Did Arbus have a right to do what she did? And while none of this is new, it does feel like Norman's piece opens a way to that more precise interrogation of the ethics of Arbus's work by pushing us past the simple binary of "the work is good" or "the work is bad"—a binary that feels particularly ubiquitous now, and undignified in the overheated discourse about art that it often fuels. Ultimately, if the Smee/Szarkowski take on Arbus is, as Norman writes, one in which "Arbus's biography, which testifies to her own 'inner mysteries,' is used to help straighten out the problem of a privileged white woman on the prowl for weirdos—a woman who once compared taking pictures to being a butterfly collector," I don't want to discount the "butterfly collector" bit. But what if what’s so often seen as a problem could once again become fact... As Norman puts it, we so often take positionality as key to understanding works of art. And how much has that uncovered for us that a responsibly equivocal stance toward an artwork—a stance that acknowledges possibilities good and bad and makes no final judgments, or doesn't rush to translate a first impression, a take, into a summary judgment—could not more effectively do?

Time, I guess, to page Sontag for those erotics of art; we might need them again...

Ironically, Sontag appears in Norman's piece as another critic determined to reduce Arbus, specifically by critique of her privilege and the perceived amorality of her voyeurism rather than by praise for some arguable desire she had to humanize her subjects. Maybe by the time Against Photography came out, Sontag too had forgotten her own edict. Or more likely, the demands of nascent image culture—and the nature of photography, versus those technologies of art that are less automatic on the part of the artist, and less readily assimilated into a media economy that goes on to inform a country's politics—had overwhelmed it.

To be clear, Sontag's take on Arbus in "America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly" is clearly the product of intense engagement with the work and Arbus's own writings on it. But I resent the harshness of the judgments—their fixity. When Sontag writes the line

What happens to people's feelings on first exposure to today's neighborhood pornographic film or to tonight's televised atrocity is not so different form what happens when they first look at Arbus's photographs.

I think: is Arbus's work about inuring us to what is terrible? Are the subjects "necessarily ahistorical," is her view "always from the outside"? Perhaps Arbus's work is "reactive—reactive against gentility, against what is approved" to some degree; is that all it is? Sontag takes Arbus to task for not being ethical with her photographs, as a journalist might be ethical, but can't the creation of a dramatic confrontation with one's own instinct to be a voyeur be a meaningful exercise; meaningful in an ethical sense, for a viewer—particularly viewers in the same wealthy and sheltered position as Arbus—if still something for which the artist should be held to account? As Norman writes, "Looking through Arbus’s lens only makes the encounter more demanding." I suppose the point is this: There's rigor and even beauty in an unequivocal stance, but also the risk of a shrillness, an antagonism, a hostility not unlike the hostility people brought to TAR—and I'm increasingly tired of assuming a hostile, suspicious, exclusively hermaneutic relationship to art...

Right as I was writing this post, I was tipped off to the publication of an essay by Garth Greenwell in The Yale Review in which he talks about an apophatic theory of the relation between art and morality: "a theory that would allow us to explore the moral work of art without limiting or prescribing that work, as certain theologians attempt to develop ways to think about God without defining God in a manner that would violate God’s freedom." Which puts precisely the words to what I'm searching for; the relation to art I would like to return to. Marked by generosity, an understanding of an artwork as necessarily multifaceted, the taking of time in the consideration of it, an assumption of good faith. There's also a line in Ben Lerner's book The Lichtenberg Figures that comes to mind: "a great work takes up the question of its origins / and lets it drop..." Maybe I'd tweak that line now: A great work takes up the question of its ultimate meaning and lets it drop...

#movies#max norman#diane arbus#susan sontag#todd field#kieran mclean#ben lerner#garth greenwell#criticism#culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Max Norman on Recording Randy for Blizzard of Oz

The Randy part starts at 17:45

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Ten SAVATAGE Tracks Ranked - A Collaboration with the 80sMetalMan

SAVATAGE! This Florida metal band reigned from 1979 to 2002, and is now back ready to unleash a new album called Curtain Call! They never received the recognition they deserved over the course of 12 mostly excellent albums. Let’s fix that here and now!

This list is part of a collaborative effort with 80sMetalMan! You can check his list here.

10. “Handful of Rain” from Handful of Rain…

View On WordPress

#80sMetalMan#Al Pitrelli#Alex Skolnick#Atlantic#Chris Caffery#concept album#Criss Oliva#Dr. Killdrums#DT Jesus#Edge of Thorns#Gutter Ballet#Hall of the Mountain King#handful of rain#hard rock#heavy metal#Jeff Plate#Johnny Lee Middleton#Jon Oliva#Keith Collins#Max Norman#morphine child#Paul O&039;Neill#Poets and Madmen#Power of the Night#progressive metal#progressive rock#ray gillen#rock operas#Savatage#Sirens

1 note

·

View note

Text

lestappen core: liking each other's post on ig through a mutual friend instead of following each other

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Amazing Spider-Man

By Devlin Baker

#marvel comics#spiderman#Spider-Man#peter parker#may parker#mary jane watson#gwen stacy#harry osborn#flash thompson#johnny storm#curt connors#matt murdock#norman osborn#max dillon#flint marko#mac gargan#quentin beck#adrian toomes#sergei kravinoff#kraven the hunter

880 notes

·

View notes

Text

This movie gives me ultimate brainrot

#spiderman no way home#peter parker#otto octavius#norman osborn#max dillon#mj watson#ned leeds#curt connors#nwh#spiderman nwh#spiderman#.🤍🎩🍰

570 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: all of them are psychic buddies

They share telepathic friend chat room

#Pokemon#Mewtwo#Paranatural#Max puckett#pnat max#mother#mother series#earthbound#mother 2#Ness#Sonic#Silver The Hedgehog#Psychonauts#razputin aquato#saiki k#kusuo saiki#paranorman#norman babcock#mp100#mob psycho 100#mob#shigeo kageyama#friend group#psychic buddies#meme#shitpost#bunch of PNGs#okay maybe saiki would probably hate it there but i didn't really wanted him to be left out#crossover#au

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

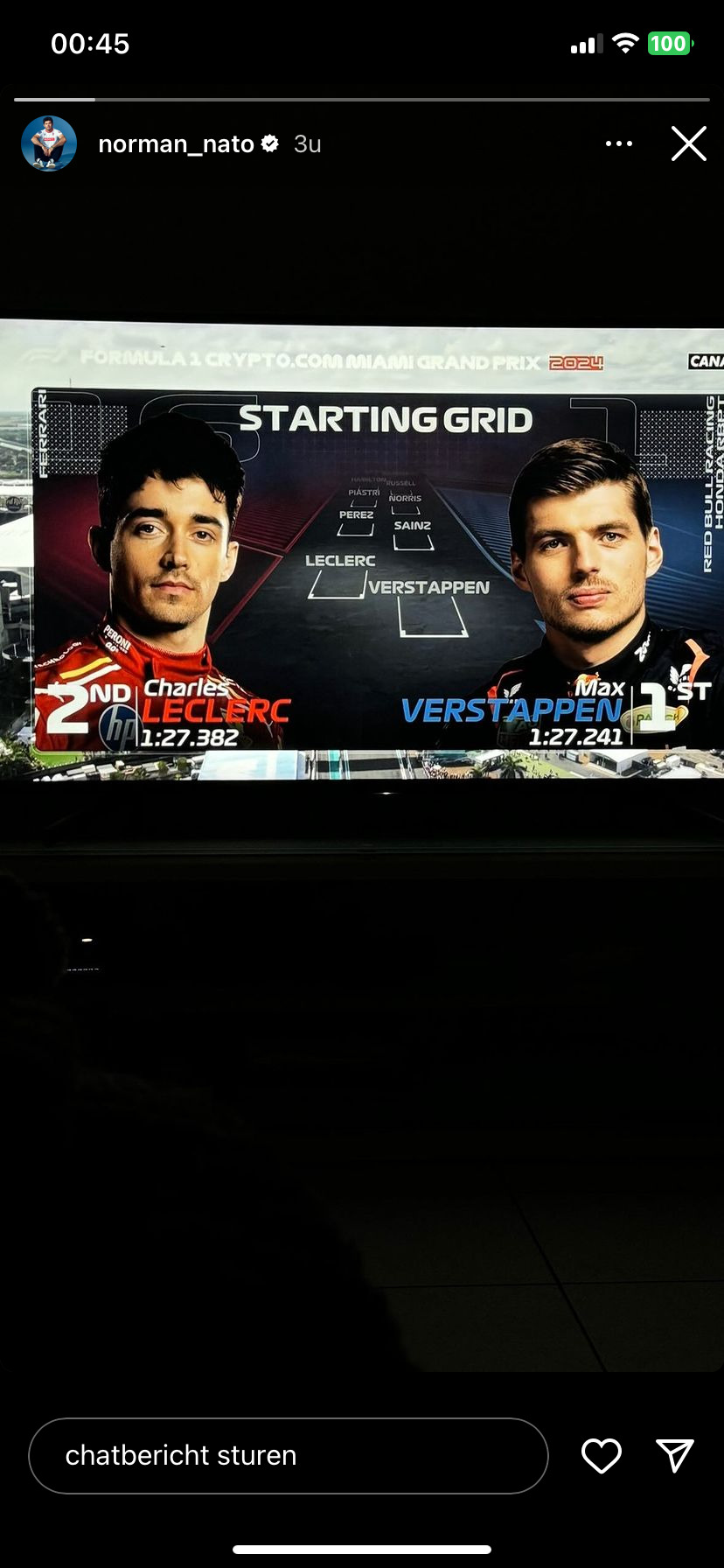

Norman Nato posting about his favourite paddle buddies today

#max verstappen#f1#formula 1#charles leclerc#lestappen#red bull racing#formula one#scuderia ferrari#formula one drivers#miami gp 2024#norman nato

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

2K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Wednesday, October 19: Savatage, “Washed Out”

R.I.P. Criss Oliva (1963-1993)

Power of the Night was Savatage’s major label debut, and as such balanced traditional ‘80s metal anthems like the mighty title track with the emerging hair metal of the hilariously ludicrous “Hard for Love”. But there was also “Washed Out” to remind everyone this was the same band that ripped through The Dungeons Are Calling: Jon Oliva’s vocals were commanding without resorting to cheap histrionics, Criss Oliva pulled out a straightforward charging riff and Steve “Doc” Wacholz pummeled his kit in classic Killdrums fashion, with all aided by a dry and precise Max Norman production that, in retrospect, sounded like a dry run for his work on Countdown to Extinction. The track was a brisk and fun headbanger that, while not entirely purposeful, reasserted Savatage’s metal bonafides during their uncertain early years on Atlantic.

#heavy metal#metal#heavy metal music#heavy metal rules#heavymusic#listen to metal#metal song#metal song of the day#song of the day#song#savatage#jon oliva#criss oliva#max norman#steve wacholz#dr. killdrums#power of the night#atlantic records#80s music#80s metal#heavy music#heavyrock#heavy rock#metalrock#metal rock#metalmusic#metal music#listen to music#long live rock#metalforever

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the 80’s Science pizzeria is one of the most popular pizzerias in the New York City, maybe because the pizza is delicious or because the place is both Family entertainment center and Science education place for kids at the same place? who know but the popularly will stop when six’s kids got missing…. later on the place get shut down and abandon,, well except the owner of this wonderful place he wouldn’t move on. Norman hire so many to become night guard of this place but somehow, people keep missing

And now it’s time for Peter Parker to work on this pizzeria

Just a little fun idea about spider-man x FNAF I hope you guy enjoy

#fnaf#five nights at freddy's#spider man#spider man au#marvel#au#peter parker#norman osborn#green goblin#hobgoblin#otto octavius#doctor octopus#doc ock#adrian toomes#vulture#max dillion#electro#quentin beck#Mysterio#sergei kravinoff#kraven#kraven the hunter#sand man#flint marko#procreate#procreateart#procreatedrawing#drawing

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

via afelixdacosta

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

This sounds Iike some perfectly soothing Sunday shit....

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

You tell 'em, Charles!

281 notes

·

View notes