#If commerce/capitalism are Natural

Note

I'm writing a sci-fi story about a space freight hauler with a heavy focus on the economy.

Any tips for writing a complex fictional economy and all of it's intricacies and inner-workings?

Constructing a Fictional Economy

The economy is all about: How is the limited financial/natural/human resources distributed between various parties?

So, the most important question you should be able to answer are:

Who are the "have"s and "have-not"s?

What's "expensive" and what's "commonplace"?

What are the rules(laws, taxes, trade) of this game?

Building Blocks of the Economic System

Type of economic system. Even if your fictional economy is made up, it will need to be based on the existing systems: capitalism, socialism, mixed economies, feudalism, barter, etc.

Currency and monetary systems: the currency can be in various forms like gols, silver, digital, fiat, other commodity, etc. Estalish a central bank (or equivalent) responsible for monetary policy

Exchange rates

Inflation

Domestic and International trade: Trade policies and treaties. Transportation, communication infrastructure

Labour and employment: labor force trends, employment opportunities, workers rights. Consider the role of education, training and skill development in the labour market

The government's role: Fiscal policy(tax rate?), market regulation, social welfare, pension plans, etc.

Impact of Technology: Examine the role of tech in productivity, automation and job displacement. How does the digital economy and e-commerce shape the world?

Economic history: what are some historical events (like The Great Depresion and the 2008 Housing Crisis) that left lasting impacts on the psychologial workings of your economy?

For a comprehensive economic system, you'll need to consider ideally all of the above. However, depending on the characteristics of your country, you will need to concentrate on some more than others. i.e. a country heavily dependent on exports will care a lot more about the exchange rate and how to keep it stable.

For Fantasy Economies:

Social status: The haves and have-nots in fantasy world will be much more clear-cut, often with little room for movement up and down the socioeconoic ladder.

Scaricity. What is a resource that is hard to come by?

Geographical Characteristics: The setting will play a huge role in deciding what your country has and doesn't. Mountains and seas will determine time and cost of trade. Climatic conditions will determine shelf life of food items.

Impact of Magic: Magic can determine the cost of obtaining certain commodities. How does teleportation magic impact trade?

For Sci-Fi Economies Related to Space Exploration

Thankfully, space exploitation is slowly becoming a reality, we can now identify the factors we'll need to consider:

Economics of space waste: How large is the space waste problem? Is it recycled or resold? Any regulations about disposing of space wste?

New Energy: Is there any new clean energy? Is energy scarce?

Investors: Who/which country are the giants of space travel?

Ownership: Who "owns" space? How do you draw the borders between territories in space?

New class of workers: How are people working in space treated? Skilled or unskilled?

Relationship between space and Earth: Are resources mined in space and brought back to Earth, or is there a plan to live in space permanently?

What are some new professional niches?

What's the military implication of space exploitation? What new weapons, networks and spying techniques?

Also, consider:

Impact of space travel on food security, gender equality, racial equality

Impact of space travel on education.

Impact of space travel on the entertainment industry. Perhaps shooting monters in space isn't just a virtual thing anymore?

What are some indsutries that decline due to space travel?

I suggest reading up the Economic Impact Report from NASA, and futuristic reports from business consultants like McKinsey.

If space exploitation is a relatiely new technology that not everyone has access to, the workings of the economy will be skewed to benefit large investors and tech giants. As more regulations appear and prices go down, it will be further be integrated into the various industries, eventually becoming a new style of living.

#writing practice#writing#writers and poets#creative writing#writers on tumblr#creative writers#helping writers#poets and writers#writeblr#resources for writers#let's write#writing process#writing prompt#writing community#writing inspiration#writing tips#writing advice#on writing#writer#writerscommunity#writer on tumblr#writer stuff#writer things#writer problems#writer community#writblr#science fiction#fiction#novel#worldbuilding

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

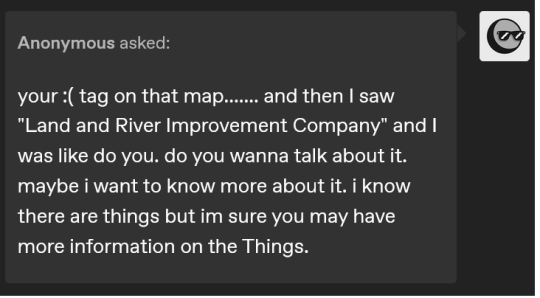

It's a big mess of hubris; the manipulative use of scientific language to legitimate/validate the status quo; Victorian/Gilded Age notions of resource extraction; the "rightness" of "land improvement"; and the inevitability of empire.

This was published in the United States one year before the massacre at Wounded Knee.

This was the final year-ish of the so-called "Indian Wars" when the US was "completing" its colonization of western North America; at the beginning of the Gilded Age and the zenith of power for industrial/corporate monopolies; when Britain, France, and the US were pursuing ambitious mega-projects across the planet like giant canals and dams; just as the US was about to begin its imperial occupations in Central America and Pacific islands; during the height of the "Scramble for Africa" when European powers were carving up that continent; with the British Empire at the ultimate peak of its power, after the Crown had taken direct control of India; in the years leading up to mass labor organizing and the industrialization of war precipitating the mass death of the two world wars.

This was also the time when new academic disciplines were formally professionalized (geology; anthropology; archaeology; ecology).

Classic example of Victorian-era (and emerging modernist and twentieth-century) imperial hubris which implies justification for its social hierarchies built on resource extraction and dispossession by invoking both emerging technical engineering prowess (trains, telegraphs, electricity) and the in-vogue scientific theories widely popularized at the time (Lyell's work, dinosaurs, and the geology discipline granting new understanding of the grand scale of deep time; Darwin's work and ideas of biological evolution; birth of anthropology as an academic discipline promoting the idea of "natural" linear progression from "savagery" to imperial civilization; the technical "efficiency" of monoculture/plantations; emerging systems ecology and new ideas of biogeographical regions).

While also simultaneously doing the work to, by implication, absolve them of ethical complicity/responsibility for the cruelty of their institutions by naturalizing those institutions (excusing the violence of wealth disparities, poverty, crowded factory laboring conditions, mass imprisonment, copper mines, South Asian famine, the industrialization of war eventually manifesting in the Great War, etc.) by claiming that "commerce is a science"; "pursuit of profit is Natural"; "empire is inevitable".

This tendency to invoke science as justification for imperial hegemony, whether in Britain in the 1880s or the United States in the 1920s and such, might be a continuation of earlier European ventures from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries which included the use of cartography, surveying/geography, Linnaean taxonomy, botany, and natural history to map colonies/botanical resources and build/justify plantations and commercial empires in the Portuguese slave ports, Dutch East Indies, or the Spanish Americas.

Some of the issues at play:

-- Commerce is "A Science". Commerce is shown to be both an ecological system (by illustrating it as if it were a landscape, which is kinda technically true) and a physiological system (by equating infrastructure/extraction networks with veins) suggesting wealth accumulation is Natural.

-- If commerce/capitalism are Natural, then evolutionary theory and linear histories suggest it is also Inevitable (it was not mass violence of a privileged few humans who spent centuries beating the Earth into submission to impose the Victorian/Gilded Age state of things, it was in fact simply a natural evolutionary progression). And if wealth accumulation is Natural, then it is only Right to pursue "land improvement".

-- US/European hubris. They can claim to perceive the planet in its apparent totality (as a globe, within the bounds of extraterrestrial space as if it were a laboratory or plantation). The planet and all its lifeforms are an extension of their body, implying a justified dominion.

-- However, their anxiety and suspicions about the stability of empire are belied by their fear of collapse and the simultaneous US/European obsession at the time with ancient civilizations, the "fall of Rome", classical ruins, etc. At this time, the professionalization of the field of archaeology had helped popularize images and stories of Sumer, Egypt, the Bronze Age, the Aegean, Rome, etc. And there was what Ann Stoler has called an "imperialist nostalgia" and a fascination with ancient ruins, as if Britain/US were heirs to the legacy of Athens and Rome. You can see elements of this in the turn of the century popularity of Theosophy/spiritualism, or the 1920s revival of "classical" fashions. This historicism also popularized a sort of "linear narrative" of history/empires, reinforced by simultaneous professionalization of anthropology, which insinuated that humans advance from a "primitive" state towards modernity's empires.

-- Meanwhile, from the first decades of the nineteenth century when Megalosaurus and Iguanodon helped to popularize fascination with dinosaurs, Georgian and later Victorian Britain became familiar with deep time and extinction, which probably contributed to British anxiety about extinction, imperial collapse, lastness, and death.

-- Simultaneously, the massive expansion of printed periodicals allowed for sensationalist narrativizing of science.

-- The masking of the cruelty in a euphemism like "land improvement". Like sentencing someone to a de facto slow death and deprivation in a prison but calling it a "sanatorium" or "reformatory". Or calling the mass amounts of poor, disabled, women, etc. underclasses of London "unfortunates". Whether it's Victorian Britain or early twentieth century United States: "Our empire is doing this for the betterment and advancement of all mankind."

-- If an ecosystem is conceived as a machine, "land improvement" actually means monoculture, high-density production, resource extraction, concentration.

-- The image depicts the body is itself is also a mere machine (dehumanization, etc.). And if human bodies are shown to be also systems, networks, machines like an ecosystem, then human bodies can also be concentrated for efficiency and productivity (literal concentration camps, prisons, factories, company towns, slums, dosshouses, etc.). This is the thinking that reduces humans and other creatures to objects, resources, to be concentrated and converted into wealth.

And so after the rise of railroads and coal-power and industrial factories in the earlier nineteenth century, the fin de siecle and Edwardian era then saw the expansion of domestic electricity, easier photography, telephones, radio, and automobiles. But you also witness the spread of mass imprisonment, warplanes, and machine guns, etc. And in the midst of this, the Victorian/Gilded Age also saw the rise of magazines, newspapers, mass media, pop-sci stuff, etc. So this wider array of published material, including visual stuff like maps and infographics could "win over" popular perception. This is nearly a century after the Haitian Revolution, so more and more people would have been able to witness and call out the contradictions and hypocrisies of these "civilized" nations, so scientific validation was important to empire's public image. (Think: 100 years prior, everyone witnessed widespread revolutions and slave rebellions, but now the European empires are still using indentured labor, expanding prisons, and growing even more powerful in Africa, etc. An outrage.)

Illustrations like this ...

It's people with power (or people with a vested interest in these institutions, people who aspire to climbing the social ladder, people who defend the status quo) looking around at the general state of things, observing all of the cruelty and precarity, and then using scientific discourses to concede and say "this was inevitable, this was natural" and not only that, but also "and this is good".

Related reading:

Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); "Science in the Nursery: the popularisation of science in Britain and France, 1761-1901" (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2011); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); "Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times" (Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Collette Le Petitcrops); “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden" (Sharae Deckard); "Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia's Plantation Economy" (Gregg Mitman, 2017); Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Ann Laura Stoler, 2013)

Fairy Tales, Natural History and Victorian Culture (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2014); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); "Shaping the beast: the nineteenth-century poetics of palaeontology" (Talairach-Vielmas, 2013); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2020)

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.2.1 What is the essence of anarchism?

As we have seen, “an-archy” implies “without rulers” or “without (hierarchical) authority.” Anarchists are not against “authorities” in the sense of experts who are particularly knowledgeable, skilful, or wise, though they believe that such authorities should have no power to force others to follow their recommendations (see section B.1 for more on this distinction). In a nutshell, then, anarchism is anti-authoritarianism.

Anarchists are anti-authoritarians because they believe that no human being should dominate another. Anarchists, in L. Susan Brown’s words, “believe in the inherent dignity and worth of the human individual.” [The Politics of Individualism, p. 107] Domination is inherently degrading and demeaning, since it submerges the will and judgement of the dominated to the will and judgement of the dominators, thus destroying the dignity and self-respect that comes only from personal autonomy. Moreover, domination makes possible and generally leads to exploitation, which is the root of inequality, poverty, and social breakdown.

In other words, then, the essence of anarchism (to express it positively) is free co-operation between equals to maximise their liberty and individuality.

Co-operation between equals is the key to anti-authoritarianism. By co-operation we can develop and protect our own intrinsic value as unique individuals as well as enriching our lives and liberty for ”[n]o individual can recognise his own humanity, and consequently realise it in his lifetime, if not by recognising it in others and co-operating in its realisation for others … My freedom is the freedom of all since I am not truly free in thought and in fact, except when my freedom and my rights are confirmed and approved in the freedom and rights of all men [and women] who are my equals.” [Michael Bakunin, quoted by Errico Malatesta, Anarchy, p. 30]

While being anti-authoritarians, anarchists recognise that human beings have a social nature and that they mutually influence each other. We cannot escape the “authority” of this mutual influence, because, as Bakunin reminds us:

“The abolition of this mutual influence would be death. And when we advocate the freedom of the masses, we are by no means suggesting the abolition of any of the natural influences that individuals or groups of individuals exert on them. What we want is the abolition of influences which are artificial, privileged, legal, official.” [quoted by Malatesta, Anarchy, p. 51]

In other words, those influences which stem from hierarchical authority.

This is because hierarchical systems like capitalism deny liberty and, as a result, people’s “mental, moral, intellectual and physical qualities are dwarfed, stunted and crushed” (see section B.1 for more details). Thus one of “the grand truths of Anarchism” is that “to be really free is to allow each one to live their lives in their own way as long as each allows all to do the same.” This is why anarchists fight for a better society, for a society which respects individuals and their freedom. Under capitalism, ”[e]verything is upon the market for sale: all is merchandise and commerce” but there are “certain things that are priceless. Among these are life, liberty and happiness, and these are things which the society of the future, the free society, will guarantee to all.” Anarchists, as a result, seek to make people aware of their dignity, individuality and liberty and to encourage the spirit of revolt, resistance and solidarity in those subject to authority. This gets us denounced by the powerful as being breakers of the peace, but anarchists consider the struggle for freedom as infinitely better than the peace of slavery. Anarchists, as a result of our ideals, “believe in peace at any price — except at the price of liberty. But this precious gift the wealth-producers already seem to have lost. Life … they have; but what is life worth when it lacks those elements which make for enjoyment?” [Lucy Parsons, Liberty, Equality & Solidarity, p. 103, p. 131, p. 103 and p. 134]

So, in a nutshell, Anarchists seek a society in which people interact in ways which enhance the liberty of all rather than crush the liberty (and so potential) of the many for the benefit of a few. Anarchists do not want to give others power over themselves, the power to tell them what to do under the threat of punishment if they do not obey. Perhaps non-anarchists, rather than be puzzled why anarchists are anarchists, would be better off asking what it says about themselves that they feel this attitude needs any sort of explanation.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

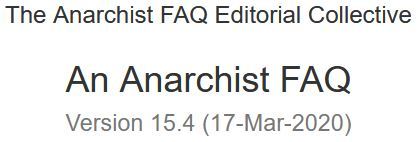

Many of your economic development plans call for the LPs to climb the "value-added chain". In a late medieval context, what value-added product would give you the most bang for your buck when it comes to timber?

Timber is a bit trickier than the classic case of textiles (where there are more links in the value-added chain from raw wool to carded wool to spun thread to plain woven cloth to dyed cloth to higher-end fabrics).

The first place to start is to shift from timber (i.e, the harvesting of raw, unprocessed logs from trees) to lumber (treating and seasoning, and sawing the logs into standardized boards, planks, beams, posts, and the like that can be used by carpenters to make furniture, housing, etc.). This requires the construction of sawmills (usually water- or wind-powered), usually downstream from the timberland so that logs can be easily floated down to the sawmill rather than going to the effort and expense of carting them overland.

The next step is to encourage the development of associated industries like furniture-making, construction...and most prized of all, ship-building. These industries continue to climb the value-added chain, because there's more money to be made from selling artisan furniture than selling raw logs and more money to be made in real estate than selling planks retail, and thus they allow you to maximize your profits from your natural resources. More importantly, if you can get into ship-building, you not only make money from selling and repairing the ships, but it's a pretty easy step from there to branch out into commerce on your own account (since you are already producing the main capital investment that seaborn commerce requires).

This is why various forms of Navigation Acts were often a key strategy of mercantilist policy during the Commercial Revolution, because if you could make sure that foreign trade was carried out by your nation's ships crewed by your sailors and your pilots and financed by your merchants, that the profits from trade would be more likely to be re-invested at home rather than exported to someone else's country.

#asoiaf#asoiaf meta#economic development#early modern economic development#mercantilism#early modern state-building#commercial revolution

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abolition of the family! Even the most radical flare up at this infamous proposal of the Communists.

On what foundation is the present family, the bourgeois family, based? On capital, on private gain. In its completely developed form this family exists only among the bourgeoisie.

But this state of things finds its complement in the practical absence of the family among the proletarians, and in public prostitution.

The bourgeois family will vanish as a matter of course when its complement vanishes, and both will vanish with the vanishing of capital.

Do you charge us with wanting to stop the exploitation of children by their parents? To this crime we plead guilty.

But, you will say, we destroy the most hallowed of relations, when we replace home education by social.

And your education! Is not that also social, and determined by the social conditions under which you educate, by the intervention, direct or indirect, of society, by means of schools, etc.?

The Communists have not invented the intervention of society in education; they do but seek to alter the character of that intervention, and to rescue education from the influence of the ruling class.

The bourgeois clap-trap about the family and education, about the hallowed co-relation of parent and child, becomes all the more disgusting, the more, by the action of Modern Industry, all family ties among the proletarians are torn asunder, and their children transformed into simple articles of commerce and instruments of labour.

But you Communists would introduce community of women*, screams the whole bourgeoisie in chorus.

The bourgeois sees in his wife a mere instrument of production. He hears that the instruments of production are to be exploited in common, and, naturally, can come to no other conclusion than that the lot of being common to all will likewise fall to the women.

He has not even a suspicion that the real point is to do away with the status of women as mere instruments of production.

-The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Frederich Engels

*meaning, women held as common property

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snippet - Forward, but Never Forget/XOXO - The Council

Silco meets the Council. And ponders his history.

Forward, but Never Forget/XOXO

Snippet:

Hatred rises like a toxic effervescence in Silco’s veins.

(These Pilties, eh, Vander?)

(These fucking Pilties.)

In a city whose lifeblood is old money, they are the crème de la crème: an elite group steeped in Piltover's rich heritage of trade and commerce. A century ago, the city was a drowsy backwater, a middling port of fishing settlements and warehouses. The Council's forefathers were Shuriman midshipmen, Ionian merchants, Noxian brigands and Demacian bureaucrats. Men and women who made their fortunes through sheer tenacity and hard graft.

Then came the boom.

Beneath the settlement lay caverns with rich deposits of minerals. Soon, smelters dotted the waterfront, and shipyards sprang up along the bay. Steel became gold. Iron turned to platinum. The age of industry dawned: Piltover blossomed into a manufacturing metropolis.

Then came the Void Wars. In a trice, the city's population doubled. Zhyunian refugees fled by boat; Noxian merchants came by steamships; Demacian scholars boarded trains and Freljordians rode in on zeppelins. Language diversified; the city grew cosmopolitan.

In the coming decades, successive waves of migrants were swept onto Piltover's shores: from noble families seeking to expand their power across Valoran to small-town traders laden with cheap luggage and big dreams. By the century's end, they'd propelled Piltover into a global megacity of palatial mansions, art deco skyscrapers and pristine streets hosed clean every morning before the business hubs threw open their gilded gates to the bon ton.

The population boom meant more houses to build, more food to eat, more clothes to wear. All of which required labor, capital investment, and raw materials.

All of which came from the Fissures.

In theory, the Undercity should have prospered hand-in-hand with Piltover. Yet little of the riches from the Fissures’ recesses was ever relished by the Fissurefolk themselves. They were cut from a different cloth from their over-the-Pilt brethren. Their ancestors were miners and craftsmen, not shipmasters and merchants. Their culture was a clotted stew of customs and dialects; most didn't even speak Piltovan. They weren't born in the city itself but in its shadow, living in close-knit riverside settlements and twilit caverns.

Physically, they resembled deepwater piranhas compared to their sun-kissed kin—narrow bones, wan skins and sharp teeth. Culturally, they were foreigners. And socially, they were inferiors.

Their economy was a rich relic of the Oshra Va'Zaun empire. Their gemcraft and metalworking industries were well-established. Their artisans were peerless and prolific. Their alchemical scholars were the backbone of innovation. They had a robust labor force, a thriving entrepreneurial class, and a history of keen ingenuity.

Their forbearers traded along a flourishing network of maritime ports and river routes. They bartered with Bilgewater; bankrolled the gold mines in Shurima; forged trade deals with Ionia. They even had stakes in the black markets of the Shadow Isles and the mercenary guilds of Noxus.

They did business with every corner of Runeterra. And they did so proudly.

A century's time would turn the glad tidings into bitter tides.

During the first wave, the Undercity's wealth was a windfall for Topside. The demand for labor and resource was insatiable. But the Undercity's resources were finite. When Piltover's population ballooned after the Void Wars, the Fissurefolk were forced to compete. Lacking the natural advantage of fertile terrain and plentiful sunlight, they had no choice but to cut corners. In a trice, the factories and mines teemed with orphans and the elderly, each one paid starvation wages and offered none of the protections aboveground. By the century's end, the Undercity was squeezed dry, a sweatshop with a single employer.

Piltover.

As the upper-city's wealth quadrupled, mercantile clans rose up, each vying for control over the mineral deposits in the Fissures. These overlords were no friends of the poor. Their purview was profit, and profit meant one thing above all else:

Exploitation.

Their first order of business was stymieing the Undercity's trade routes and keeping its resources under lock and key. The collapse of the old Sun Gates and the flooding of the Undercity’s ports gave them the perfect pretext. The borders were sealed off in the guise of a safety net. The only routes were now through Piltover's Bridge, and each shipment was heavily taxed.

In time, the Undercity’s local markets choked. A slow strangulation of wealth reduced former artisans and alchemists to scavengers. Tariffs trapped them in a perpetual cycle of debt and debasement. Once-proud traders stooped to selling their own daughters for coin. Others tipped over into outright smuggling.

Then Piltover launched its second phase: a systematic strangulation of the Undercity's voice.

Fissurefolk were barred from owning or leasing property aboveground. Their children were denied access to Topside schools. Their customs were deemed barbaric. Their traditions were branded as backward. Their dialect was derided as guttural filth. They were derogatorily referred to as Sumprakers—as if their entire existence was an aberration.

By the century's end, Piltover had transformed from a trading partner into a hegemony. The Fissurefolk were no longer perceived as citizens, but as the Other.

An enemy within.

Soon, Topside began consolidating power by buying up land around the Fissures. Displacing the poor and demolishing their homes, they drove them deeper and deeper belowground, while putting the leftovers to use. Historic districts were privatized. Temples were razed. Marketplaces were shut down. The Undercity was reduced to a febrile womb of raw material, ready to be ravaged.

And ravaged it was.

When the first mining rig was installed, the Fissurefolk rioted. The unrest was put down. More mines followed, and more violence. It wasn't until the Enforcers were established as a body of justice that the tide turned in Topside's favor. These overseers were a law unto themselves, their ranks composed of mercenaries and miscreants. Their uniforms were black; their hearts were blacker. Their methods were a brutal amalgam of medieval torture and modern bureaucracy.

Under the banner of peace, the Enforcers were tasked with quashing dissent belowground.

They did so—brutally.

Piltover's third phase was total dominion.

The first mercantile houses had grown rich off the Undercity's spoils. But the new generation hungered for something more: absolute rule. They were no strangers to political maneuvering. Their forefathers had been shrewd tacticians: men and women who'd honed their wits through war, diplomacy and backroom deals.

They knew how to twist the knife, and keep their own hands clean.

Before long, they'd allied with Piltover’s industrial magnates and the monied elite. Together, they formed a cabal of oligarchs, each as ruthless as they were influential. Thus, the Council was born: a body of seven self-appointed sovereigns charged with regulating trade, enforcing laws and levying taxes.

They saw the Fissurefolk as a means to their own end. Disregarding their petitions for better sanitation, downplaying the contributions of their labor, and turning a blind eye to the rampant pollution, they proceeded to carve the Undercity's soul from its body.

When the Fissurefolk protested, the Council responded with Enforcer raids.

And bloodbaths.

By century's end, the Council had built a wall of bureaucracy between themselves and the Fissurefolk—most of whom were treated with neo-colonial contempt. Meanwhile, their wealth continued to reach dizzying heights, with every merchant ship that sailed through the port's grand arches and every sculpture patronized by celebrated virtuosos in their mansions.

The Hex-Gates only quadrupled their fortunes. With every invention by Talis, investors flocked and the Council’s influence grew. The wealth they had hoarded was now limitless. They could build a brand-new city, if they so desired. But why should they, when the Trenchers had already done the hard work for them?

Today's Council—Hoskel, Salo, Bolbok, Shoola, Medarda, Kiramman—are Piltover's pivotal political force, decreeing laws with a gesture from their grand parlors. They're the ones who decide whether jobs are created or lost, how many schools are funded, what taxes are levied.

They make decisions that affect every citizen in the city—every bloody day.

They are also corruption incarnate. Yearly, they’ve swallowed over one-third of the allocated Undercity budget, without accounting for a single cog. Between them, they preside over an empire of private business interests in everything from real estate to racehorses, stowing away their wealth in Demacian bank accounts, Noxian jewelry splurges and private islands dotting the annexed Ionian shores.

To them, Silco's coal-mining origins are as offensive as a rat turd in their caviar. Among Topside's upper-crust, he's a social climber, a rabble-rouser, and a scabrous opportunist. He wasn't born into privilege: he made his wealth through the cutthroat crudeness of industry.

More offensive still, he keeps a singlehanded stranglehold on his fortune, no different from a smuggler stowing all his coins in his codpiece. He never invests in stocks or allows Piltovans to buy shares in his enterprises. Like his factories, everything he owns belowground—publishing houses, restaurant chains, repair garages, gyms, nightclubs, salons—employs Fissure-bred workers, and is rumored to be a front for funding anarchism.

As if that weren't bad enough, he has no inhibitions in debating money or politics in their glittering ballrooms. Worse, he mocks them for entertainment—all while displaying impeccable manners.

Case in point—

With grave courtesy, Silco bows his head, "Councilors."

#arcane#arcane league of legends#arcane silco#silco#forward but never forget/xoxo#forward (never forget)/xoxo#arcane jinx#jinx#arcane mel medarda#mel medarda#arcane jayce talis#jayce talis#arcane cassandra#cassandra kiramman#arcane hoskel#arcane shoola#arcane bolbok#arcane salo#arcane vander#vander#snippet

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prestige Class Spotlight 13: Balanced Scale of Abadar

(art by Ioana-Muresan on DeviantArt)

We’ll cover him eventually, but Abadar is the god of civilization, commerce, and advancement, and so his faith focuses not just in advancing and improving society, but also helping to uplift even the lowest dredges for the betterment of all, at least in theory. It can sometimes be hard for Abadarites to differentiate merchantilism from capitalism.

However, there are those among them that seek, above all else, to make sure that wealth stays balanced. These are the ones who return relics and heirlooms to their rightful owners, who go out and reclaim unclaimed treasures for modern civilization from tombs, dungeons, and other places where the wealth would go to waste.

These are the balanced scales, a branch of divine casters among the faithful that draw upon greater mysteries of the Master of the First Vault, and can even draw upon his many wonders in their effort to bring prosperity to civilization.

This is an interesting one, as it’s a prestige class that actually came out before the Pathfinder RPG itself actually did so, making this a D&D 3.5 prestige class. However, it’s fairly easy to convert over, replacing certain skills with their more modern counterparts.

It is, however, a very thematic prestige class given the deity they answer to, and the powers they offer can be quite useful.

This path requires a basic understanding of disabling locks and traps, as well as appraisal. Furthermore they must also have mastery over divine magic, enough to cast 3rd-level spells. This means that pretty much any divine spellcasting class can take part in it, though obviously minor casters tap into it later than others.

Naturally, as priests of Abadar, the Balanced Scales continue their training into divine magic, though perhaps at a slightly slower pace at first.

Magical locks and traps are often a problem in tombs and ruins, and so these mystics are blessed with a knack for disabling them.

They also learn to discern what is valuable at a glance, useful for determining what to take from a hostile environment.

The biggest treasure hoards are sometimes too big to be carried out practically. As such, they learn a bit of magic to turn an ordinary sack into a bag of holding for hours at a time, increasing their carry capacity significantly. Later on, they can make a bigger bag or create two at once.

Their training also includes lessons on bargaining and how to grease the wheels of society with the universal lubricant of money. This also applies in a different way when bargaining with bound outsiders and other beings in exchange for their supernatural services.

Those that distinguish themselves as devoted servants of Abadar gain access to a privilege that few beings period, let alone mortals, gain access to, which is access to the First Vault, the cosmic structure where Abadar keeps the first perfect example of every object that civilization has ever made across the entire universe, from art objects to practical items (or at least, very good replicas of them). Once a week, a balanced scale can draw upon the First Vault itself to conjure one of these items (or again, a replica) to their hands, up to a limit on value based on their mastery of divine magic. At first, these objects are mundane, but later they can be magical. However, these objects are so incredibly perfect that they cannot be sold, both because merchants would immediately pick up on their unnatural origin, but also because it is against the tenets of the Abadaran faith to sell false goods.

Finally, they can take their ability to access the First Vault to it’s logical extreme and actually go there, using it as a stepping stone to teleport either somewhere they’ve been before within range, or to the nearest temple of Abadar. However, there are two caveats. One is that since they have to travel physically through the vault to get to the exit portal that leads to their destination, it is not instantaneous. The other is that the raw amount of perfection on display is disorienting and overwhelming, threatening to sap the mind with the wonders on display. Thankfully, it’s physically impossible to swipe something while on this sojourn, preventing the balanced scale from being an unwitting or coerced accessory to a cosmic theft.

This prestige class has a nice mix of utility powers that make for a thematic arsenal for your lawful cleric/paladin/druid/inquisitor/warpriest that specializes in tomb-breaking and loot-gathering. Additionally, the ability to conjure whatever item you need for a situation makes this arguably Paizo’s first attempt at making gadgeteer character options, which I can appreciate. Your exact build will vary based on your class, but rest assured you’ll definitely have an element of utility problem solving and social interaction.

This really is a flavorful prestige class, After all, not every god lets their devotees borrow things from their private toy box, as it were. It is good time to remind oneself, however, of how much divine power and the benefits of such are a privilege to be given out, but also rescinded if the recipient proves unworthy. Now, one might think that getting to the point where you can get access to such wonders might put one beyond philosophical failings, but arrogance is also a hell of a drug.

Devastated by war and the fall of the royal lineage, the nation of Khomat is on the verge of collapse, but the followers of the Wealth God have a plan to stabilize the region and set up a new government with only a gentle guiding hand on their part, or so they claim. But in order to fund this transition of power, the church will need a new source of income, and the tombs of the old royal line are tempting targets indeed.

A hundred years after the entire Sovaca coast fell into the ocean at the will of vengeful gods, there are still remnants of their civilization that have withstood the cataclysm and the a centuries worth of ocean water. These days, both gillmen and locathah priests lead expeditions into these ruins, the former to reclaim the legacy of their forefathers, the latter to reclaim what the surface Sovacans took from them.

Ages ago, a shadowy cult laid claim to hundreds of souls through false promises in the land of Nemwa, dragging them en masse to the shadow plane and their velstrac masters alongside the art and sculpture of their culture as a trophy. Now, one brave soul blessed by the gods of civilization is assembling a party to free those souls and rescue those symbols of their culture.

#pathfinder#prestige class#balanced scale of abadar#gillmen#locathah#Dark Markets A Guide to Katapesh

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Kettering; land of Artistry and Pride.

south-east corner of the continent, primarily orc citizens

Character SHORT List:

Dima Grimscale

Dragonrider 2.0

Erick Livan

Felix Enrel

Harry Enrel

Julia Violet

Lindsey Livan

Miss Seashell

Pent Enrel

Kent Darkwater

thomashetzler on Unsplash.

Geography:

Great Kettering is based on the UK islands physical geography*. Great Kettering has slight weather changes with the seasons, primarily an increase in humidity and less rainfall in the summer months. Mostly known to be cold and wet overall. Tsunamis can happen along the coast to the south, and south-east. Earthquakes are small distant shakes from the far west. Droughts are rare and only in very dire situations. Lots of coastal towns are on the coast cliffs rather than the coast, and therefore are generally safe from the usual tsunamis that occur. Boat living... isn't uncommon yet dangerous depending on the time of year (hence the phrase, sturdy like GK's fishers). Earthquakes aren't an issue just noticeable along the west border. Great winters are prepared for a lot like Solistal does.

*but only when I feel like it lol

Architecture:

GK is a mix of my personal headcanons for orcs and fantasy England. The most common form of landmark is the stone/moss circles, each with their own pattern, like a fingerprint. Generally, only those born in the area will be familiar with these landmarks without a map. Because of this, the moss circles are speculated to be linked to the orc-ish Aeons religion. Kelp forests are a special sight along GK coasts. The most well known location in GK is the sunken castle, and its bridges to nowhere. One explanation is that the coastal cliff was washed away and the castle was too heavy so it fell into the ocean to be forgotten, another blames the mythological 'Thorns' for putting it their during one of their tantrums. For a foreigner, the knight tourneys are a highly anticipated event due to the invitation of both the highest king and lowest servant.

Most towns start with a safe drinking water source in the middle, market and community buildings around that, then common dwellings around those. For Kettering, the capital, there are 'districts' that citizens must get permits to build inside. These districts help with deliveries, city planning, guard patrols, and lock down procedures. Again, most towns are situated along the south coast, and it's either the direct coast or, if the cliffs are too severe, then it'll be as high on a hill they can get while still in viewing distance of the sea. On the north side of Great Kettering, it still follows the idea of the highest hills. Including Kettering, which itself has a 'natural moat' around it, although the city surrounding the castle has since expanded further around the lake as well. In smaller towns, people are clumped together, tiny and people live in each others pockets, whereas bigger towns are more spacious. That said, construction is trending towards taller rather than wider. Common structures are in the easy to acquire and transport materials, where the elegant marbles and quartz are left for Kettering or other religious sites in other large towns.

Trade/Commerce:

GK trade away seafood for different 'exotic' foods and their artisans are highly sorted after. They import from Solistal for specialty materials to craft with. Kamikita holds a chokehold on trading routes and this frustrates GK. They import from Birkina for island herbs and spices, as well as dyes for their crafts. Can be self-sufficient if trades were to be suddenly cut. The world trade is currency based but smaller store keepers accept barters... if you can talk them into it. Solistal's ores/minerals and their jewelcrafters are flaunted as expensive goods and a highly requested import. Whereas 'seals' or magical coins are the least sought after. GK's embroiders are the most asked for export.

sapegin on Unsplash.

Other Parts:

For Great Kettering. 1 / 2 / 3 / 4

For Solistal. 1 / 2 / 3 / 4

For Kamikita. 1 / 2 / 3 / 4

For Birkina. 1 / 2 / 3 / 4

#ted talks#the klenith saga#tws#my writing#my worldbuilding#worldbuilding#fantasy#high fantasy#great kettering#orcs#geography#architecture#commerce#character list#characters#kettering#settings#long post#unsplash#artistry and pride#undescribed images#part 1#part 1 of 4

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Less than two months ago, parts of Port-au-Prince seemed like a ghost town. Streets and parks normally bustling with commerce and people were nearly empty.

Market women, who normally lined the roads selling everything from food to second-hand cellphones, were few and far between. Charred tires, piles of rocks, and makeshift barricades, the remnants of months of protests against the government, could be seen throughout the capital. The once pristine Petionville, an affluent suburb of Port-au-Prince, was barely recognizable in some parts, with trash overrunning the streets.

Over the last 18 months, Haiti has been in the throes of a perpetual cycle of protests — some violent — and unrest that has destabilized the country for weeks at a time. Years of pent-up frustration over rising inflation and basic costs of necessities on the island came to a boil during a week in July 2018, when the Haitian government nearly doubled fuel prices over night. The move, which was a condition for future aid imposed by the International Monetary Fund, sparked outrage that spilled into the streets, leaving Haiti’s capital charred by flames and fury. People were barricaded in their homes, offices, restaurants, while thousands of people took to the streets rallying against the fuel hike.

The Best Western, which permanently closed its doors on Oct. 31, loomed over Petionville as a symbolic and literal reminder of the state of affairs in Haiti. For many, the U.S.-based hotel chain’s arrival in the country had marked a positive new turn in Haiti following the January 2010 earthquake.

Now, it seems, the hopeful signs have come undone. While daily life in Haiti has always been difficult for most Haitians, the past 18 months on the island have been particularly hard. As the country finds itself in the throes of a fluctuating political, economic and social crisis, the capital city has been virtually paralyzed, with schools, businesses, and banks closed for days, if not weeks, at a time.

This was not the Haiti anyone had hoped for 10 years after the disaster.

The 7.0-magnitude earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010 killed roughly 300,000 people and displaced nearly a million more. While the epicenter of the earthquake was only 16 miles from Port-au-Prince, the tremor could be felt as far away as Cuba and Venezuela. The devastation was the single greatest humanitarian crisis the small-island country had ever faced. The capital’s already fragile infrastructure was nearly decimated, while the airport and seaports were rendered inoperable. The National Assembly building and Port-au-Prince Cathedral were also destroyed.

“There was a natural expectation that things would be done differently from there on because it was such a big tragedy and the way that that tragedy unfolded was in itself a reflection of choices that were made historically in the country in terms of governance,” said Ludovic Comeau Jr., professor of economics at DePaul University and former chief economist of Haiti’s central bank.

According to Comeau, most of the country’s wealth was severely impacted by the earthquake because of the centralization of Haiti’s economy in Port-au-Prince, with damages totaling 120 percent of the country’s GDP.

“[It was] not only our hope, but almost our certainty, that things would be done differently [in Haiti] and within the next 20 years, Haiti would be an emerging economy,” Comeau said. “It’s certainly not the path we took. There’s no way Haiti will become an emerging economy by 2030.”

“This is worse than the earthquake”

Melinda Stephanie Dominique, a medical student at Quisqueya University, spent the fall semester waiting to find out when it would be safe enough for her to return to school. Instead of studying for exams and walking the halls of her campus with her classmates, she was home weighing the risks she would face if she did decide to venture out.

“We watch the news, we see the videos,” said Dominique, who has three years left in her program. “We’re not going out just like that. Especially when you can hear the bullets yourself. There’s no way to know whether you’ll be able to make it back home.”

While some schools sent notice and formally closed their doors at the height of the protests, others simply shuttered their doors because students stopped coming in. In Dominique’s case, Quisqueya University opted to suspend classes until the protests subsided.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen in this country,” Dominique said.

The political and social turmoil in the country is exacerbated by a feeling of hopelessness that has taken hold in the country, in large part due to the disappointment surrounding earthquake relief and reconstruction efforts.

For the first time in decades Haiti had the world’s attention. However the overwhelming consensus is that the Haitian government and members of the CORE Group — composed of the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General, the Ambassadors of Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, the European Union, the United States of America, and the Special Representative of the Organization of American States — squandered what little chance Haiti had to emerge as a growing and stable economy.

Comeau says the last decade is one of “missed opportunities, endemic corruption sustained by an equally endemic impunity.”

“You have a situation where public officials in charge of budget in some administrations pilfer the country’s money, and there’s no accountability,” he said. “There’s this mentality that people can do whatever they want, including mismanaging and essentially embezzling public funds. You see all of this culminates in the PetroCaribe scandal.”

In 2005 Venezuela launched the PetroCaribe program that allowed Caribbean countries to buy oil at market value, with only a portion of the payment made upfront, while the remainder of the balance could be paid through a 25-year financing agreement with a 1 percent interest rate. The aim of the program was to spur development and fund social programs in recipient countries. In Haiti, however, nearly $3 billion of the PetroCaribe funds went missing, with Haitians having little to show for the billions of dollars that were poured into the country.

“There’s nothing that can be shown for that $3 billion,” Comeau said. “This is what I’m talking about when I say missed opportunities. Here you have this money from 2008 – 2017 that was available to do something great. We could have built a major hospital in every major region in the country. We could have built universities in every department. We could have improved our infrastructure and modernized, which would have attracted foreign investors. We missed all of this.”

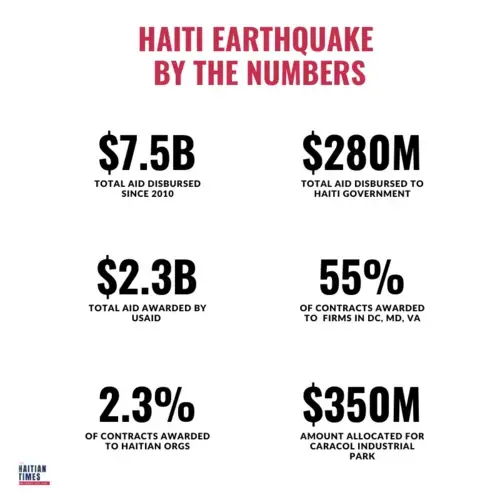

Since the earthquake, more than $7 billion in foreign aid has been disbursed to Haiti, according to research from the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Haitian organizations and firms, however, received just over 2 percent of the funds that had been allocated to the country.

Criticisms and accusations of fraud, mismanagement and misappropriation of funds plagued relief efforts for years, spurring accountability campaigns demanding answers to the whereabouts of billions of dollars that were meant for reconstruction efforts in Haiti.

Bill and Hillary Clinton were at the center of many scandals surrounding Haiti and the relief funds.

In the days following the earthquake, Bill was tapped as co-chair of the commission tasked with allocating relief funds, while Hillary oversaw more than $4 billion Congress earmarked recovery efforts. However, emails released through a Freedom of Information Act request, revealed officials from the Clinton Foundation — the couple’s personal philanthropic fund — were looking out for bids and proposals from the Clintons’ friends and associates. In the end, the foundation secured 34 projects in the country, including the $350 million Caracol Industrial Park project. The project led to the creation of 10,000 jobs in Haiti, instead of the 65,000 the Clintons promised.

“Billions of dollars were donated to Haiti after the earthquake and we have no idea what was done with that money,” Comeau said.

“In 10 years, nothing has changed,” Dominique said. “We didn’t move forward; we stayed static.”

For many, the current state of affairs in Haiti is worse than any damage the country suffered because of the earthquake. This was more devastating because of its “man-made” nature.

The chain of events to follow would set the stage for a Haiti that many are saying is at its lowest point ever. The Kot Kob Petrocaribe movement would highlight more than ever the endemic corruption in Haitian politics, and pave the way for the dismissal of prime ministers and eventual calls for the resignation of President Jovenel Moise. The movement, which started on Twitter, has since been co-opted and used by Haitian politicians and oligarchs to further their political interests by calling for the ouster of Moise.

Haiti’s already fragile tourism sector has been one of the biggest casualties of Haiti’s unrest. Following the earthquake, former President Michel Martelly made a big push for tourism in the country, with then-Minister of Tourism Stephanie Voulledrain leading an international branding tour, selling Haiti as an untapped tourism treasure trove.

Several fruitful projects began as part of the effective branding campaign. Airlines added flights to the country, new hotel brands were drawn to Port-au-Prince and more and more members of the Diaspora and their friends made their way to Haiti for vacation, conferences and more.

However, in a matter of months, years of work has been reversed. Best Western closed its doors. Delta ceased flights to Haiti, while other carriers significantly reduced their service to the country. Popular resorts and hotels like Decameron Indigo Beach Resort and Spa, and Karibe are virtually empty.

Searching for understanding

There are several theories as to why Haiti is in the state it is in, despite the billions of dollars in aid and donations the country received. Some point to neo-colonialism, imperialism and U.S. intervention, while others place blame on the Duvaliers, the corrupt Haitian government, or the lack of engagement among the Diaspora. The truth is, it’s a melange of it all, which is what makes imagining what comes next for Haiti so difficult.

“The Haitian-American convention did away with Haiti’s sovereignty and it’s a sovereignty that Haiti has never gotten back,” Alain Martin, director of The Forgotten Occupation, said. The documentary tells the story of the U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 from the perspective of Haitian historians, authors, journalists and politicians. “To this day, nothing happens in Haiti without the say-so of the State Department.”

The Haitian-American Treaty of 1915 gave the U.S. control over Haitian finances, and the right to intervene in Haitian affairs whenever the U.S. government deemed necessary. That same year, the U.S. government placed Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave as president of Haiti, making him the first leader in the country under the U.S. occupation.

“He represents the father figure of the modern Haitian president. Ever since Dartiguenave, with maybe one or two exceptions, every president we’ve had, has been beholden to the State Department,” said Martin.

“You have to look at Haiti as a Shakespearean tragedy. Those of us who truly love Haiti and would like to see the country move forward, don’t have the physical resources to make that happen,” he said. “How can we fight against the State Department? We need allies that we simply don’t have. What the US wants to happen in Haiti is what��s going to happen.”

So what comes next for Haiti?

“The change will have to come from the U.S.,” Martin said. “We need to build a leftist movement in the U.S. that elects leaders that are going to have different policies toward Haiti. But it’s a long shot. Regardless if there were Democrats or Republicans in power in the U.S., their foreign policies toward Haiti have never changed.”

As for Moise, he at least has public support from the U.S., which is enough to keep him in power for now. Over the last three months, U.S. officials have made their way to Haiti or Haitian communities in the United States to “encourage dialogue” over the political impasse that has held the country in its grip for almost two years. Their efforts have been met with gratitude from some and with anger from others.

“There’s always a segment of Haitian society that is looking to the U.S. to be a sort of savior for the county,” Martin said. “They are incapable of seeing Haiti foster its own destiny and barely its own institutions to get the country going. It’s a subconscious collective insecurity that we do not have the capability of doing it on our own.”

In October 2019, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Congresswoman Frederica Wilson — who represents the largest Haitian constituency in the U.S. — participated in a roundtable discussion with members of South Florida’s Haitian community over the growing unrest in Haiti.

Ambassador Kelly Craft’s November 2019 meeting with Moise was met with anger and disapproval from Haitians over what they perceive to be U.S. interference and meddling. And just last month, Under-Secretary of State for Political Affairs David Hale met with members of the opposition and various Haitian business leaders in a closed-door meeting where he pressed for a functioning government that can work together.

“Haitians in Haiti acknowledge now that the Diaspora is the backbone of Haiti,” Comeau said. “The Diaspora is the primary source of foreign funds in the country.” In 2019 the Diaspora sent $3.5 billion to Haiti. While remittances are primarily sent from those living in the United States and Canada, more money is starting to come from Chile and Brazil, where there are growing Haitian communities.

“The Haitian government needs to think more strategically in terms of Diaspora remittances,” he said. “Most of the money sent is spent on consumption. Haiti needs to tap more systematically into the resources of the Diaspora.

We need to have Haitians in the Diaspora invest in Haiti instead of sending money.”

One of the consistent U.S. voices when it comes to Haitian / U.S. affairs has been Marco Rubio, whose comments regarding Haiti have fluctuated from supporting the will of the people calling for Moise’s ouster, to urging calm and support for Moise.

While protests had subsided and a sense of normalcy seemed to return to Haiti as the 10th anniversary of the quake approached, what happens next is uncertain, and Haitians remain discouraged.

“The earthquake came and there were so many promises to build back better,” Martin said. “Yet the earthquake is forgotten, the people who died in the earthquake are forgotten and the promises made have been forgotten.”

#Haiti#Haiti Since the Earthquake: A Decade of Empty Promises#bill clinton#hillary clinton#clinton foundation

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In countries where modern civilisation has become fully developed, a new class of petty bourgeois has been formed, fluctuating between proletariat and bourgeoisie, and ever renewing itself as a supplementary part of bourgeois society. The individual members of this class, however, are being constantly hurled down into the proletariat by the action of competition, and, as modern industry develops, they even see the moment approaching when they will completely disappear as an independent section of modern society, to be replaced in manufactures, agriculture and commerce, by overlookers, bailiffs and shopmen.

In countries like France, where the peasants constitute far more than half of the population, it was natural that writers who sided with the proletariat against the bourgeoisie should use, in their criticism of the bourgeois régime, the standard of the peasant and petty bourgeois, and from the standpoint of these intermediate classes, should take up the cudgels for the working class. Thus arose petty-bourgeois Socialism. Sismondi was the head of this school, not only in France but also in England.

This school of Socialism dissected with great acuteness the contradictions in the conditions of modern production. It laid bare the hypocritical apologies of economists. It proved, incontrovertibly, the disastrous effects of machinery and division of labour; the concentration of capital and land in a few hands; overproduction and crises; it pointed out the inevitable ruin of the petty bourgeois and peasant, the misery of the proletariat, the anarchy in production, the crying inequalities in the distribution of wealth, the industrial war of extermination between nations, the dissolution of old moral bonds, of the old family relations, of the old nationalities.

In its positive aims, however, this form of Socialism aspires either to restoring the old means of production and of exchange, and with them the old property relations, and the old society, or to cramping the modern means of production and of exchange within the framework of the old property relations that have been, and were bound to be, exploded by those means. In either case, it is both reactionary and Utopian.

Its last words are: corporate guilds for manufacture; patriarchal relations in agriculture.

Ultimately, when stubborn historical facts had dispersed all intoxicating effects of self-deception, this form of Socialism ended in a miserable fit of the blues.

Karl Marx – The Communist Manifesto

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi, I see it is in trend to have your own Winx AU these days and I mean, who can blame us? (Y'all doing a great job guyss💕). I may have one too and I finally decided to share some lore.

I did worldbuilding on some of the planets, but first a short intro.

Magic Dimension

The Magical Dimension is organized into planets, but these are more like continents or or very big states. Thanks to magic, various points of communication have been created, there can be official portals, in fact they have created pillars that keep them always open by exploiting the magic of the planets themselves, sea portals, ecc. In short if you don't have a ship nor you have energy and skills to waste in teleportation, you can travel between planets by using these portals, all you need to do is to pay a little fee.

The most prominent planets are Domino, Solaria, Linphea, Callisto, Andros, Eraklyion, Zenith, Melody, Whisperia, Magix and then Earth. These 11 planets are kinda like the 19th Century Europe of the Magic Dimension, geographically really close to each other and always fighting and trying to gain the upper hand.

Domino, Solaria, Eraklyion (half-decayed), Whisperia all have 4 an imperialist pasts, especially Domino. Domino loves conquest and before its fall, it was the richest and most powerful planet in the entire Dimension. Every each planet has been under Domino's influenced sometime in its secular history. Both Solaria and Eraklyion want to be the new Domino, Whisperia (The planet of Witches, one of the few planets to have not been created by The Great Dragon, but The Phoenix) just wants to mess around and has a taste for chaos.

Beyond them there are other prosperous and wealthy planets, but decidedly more discreet and with no delusions of grandeur.

Let's start with the first planets were going to talk about:

SOLARIA: How to get along with Witches☀️

Territory: The whole of Solaria is shaped like a spiral, lapped by the sea from both inside and outside. The outer skeleton of the spiral consists of small mountains. The inner part of the spiral is mostly flat. It may resemble a Nautilus.

Despite year-round sunshine and nonexistent rainfall, Solaria had a varied expanses of fields, flowers, low shrubs and flashes of small forests. Water comes from the mountains and collects in small streams and in many underground aquifers and gorges.

The spiral is divided into 3 coils, the innermost and most fertile are the 1st and 2nd coils. The 3rd loop, the outermost, is way more rocky and desertic.

The inner coasts on the 1st and 2nd spirals are beautiful, endless expanses of sand and between these 2 spirals the Solaria Reef opens up in the middle of the Solaria Sea. The outer shores are rocky of almost gray/white stone. At the end of the 3rd loop, you can see stacks in the sea: the moonstones.

There are 3 suns, Solas, Icarus and Albus, and 2 moons, Koray and Kale. The 2 moons are the most visible in the 3rd spiral, where they dominate night and day in the sky. In the 1st and 2nd spheres they are less visible.

Climate: Year-round sunshine, mild temperatures, neither too hot nor cold. It almost never rains.

Population: Solaria has a very compact population where fairies and witches seem to live together almost in peace. Ofc there are the classic squabbles, but they are very dumb all based either on clothing or prejudices and dumb stereotypes, which both witches and fairies have. This is due to the dual nature of the planet, both planet of light, sun, and planet of moon.

The three main cities are Surya, Teoma and Aku, on the 1st, 2nd and 3rd spira respectively.

Surya is the capital, royal city, political and administrative center, and has a prevalence of light magic users. Teoma, center of commerce, famous for entertainment, nightlife and one of the fashion and movie industry capitals of the Magic Dimension. Aku, the city of the moon, is where the majority of witches live. Witches in Solaria take the name of enchantresses, and they mostly have light-related powers despite being witches (Chimera and Cassandra are great examples. These bitches are two enchantresses). Aku is home to the Beta Academy, and while sun-related spells are preserved on Surya, Aku has archives of moon-related spells. It is a predominantly academic city, and has its own small Inner Council and its own autonomous government, with an attached aristocracy. Stella's mother, Luna, is an enchantress and she is from Aku. In Aku Luna is still referred to as the Queen of Solaria and she is the ruling monarch de facto of Aku and its county.

Solarians are generally very open, sociable, but at the same time a bit narcissistic and self-centered. Often obsessed with themselves and vanity, they would all love to be famous, making Solaria the planet of gossip, reality TV, and tabloids. Of note is their ubiquitous sincerity and sense of style.

Domino and Solaria have always been allies as two neighbors with common boundaries, never betraying each other and thick as thieves. They both exert their influence on lesser planets. The County of Aku also gets along with Whisperia and have rich commercial and cultural exchanges.

The general architectural style is rooted in Rococo pageantry, the royal palace is full of mirrors, and the cities of Surya, Aku and Teome are chock-full of fountains, gardens, water features and fine palaces of marble and white stone. Gold abounds on Teome and Surya, whilst Aku is stuffed with silver at every single corner.

Language: Solese. Very melodic language, it could be ascribed as a mixture of French and Spanish. Obv the standard language of Magix is spoken.

Politics: Monarchy. Solaria loves Radius, long live their king. Radius is a quiet, moderate king and with the aid of his crew of ministers keeps the rest of the Solarian monarchy in check and tries to get everyone to get along. However, each city in Solaria has its own small council by election, in the case of Teoma and Surya these councils constit of the mayor of the city and his men. In Aku things are a bit different, the city has a mixture of aristocrats and common people with long historical roots, and so it has retained a certain independence from the central power. Radius knows that Aku has different needs as The Moon City and he respects that, posing more as an overseer than a monarch. The sovereign of Aku is de facto Queen Luna, Stella's mother.

Solaria is a rich planet, the economy is rampant and the entertainment and fashion industries are a mainstay. The lifestyle of many Solarians is lavish and they do not hesitate to indulge in a few vices.

Religion and Co : The focus is placed on the 3 suns and their behavior; they are true deities and livelihood of the planet along with the 2 moons. The Great Dragon is also a central figure.

Much attention is placed on crystals and their meanings and properties. Cuisine? Rich, expensive and sweets are a blast: land of gluttons.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

when i was a kid i was so poor nature was the only place i had to be who i was. to feel accepted. to encounter god without the constraints of class. church did not provide this to me. nature did. the destruction of nature is the destruction of god's method of communicating with his people, especially the poor. estate and low incoming housing that violates the sanctity of nature and space by forcing people into close proximity, proximities that encourage crime and disaffection, authorities who allow those spaces to fall into disrepair and refuse to treat both the nature and the people in those spaces with dignity, violate both essential humanity and divine directive. humans need nature the way we need god. we will encounter god in nature before we ever encounter him in a church. these thoughts are not particularly coherent but i feel close to the child i used to be, who was very poor, who sank into nature because there was nowhere else for me to be, who found god in the little rivers and the grass, the sky, the clean air, and feeling close to her i feel close to the children now who are deprived of those things, children in the inner city, in neighbourhoods that are made dangerous through poverty and systemic neglect, in cities being destroyed by bombs, children and their families whose right to take up space is being denied them by the erosion and destruction, and the violence those things entail, of the spaces in which they life. god is in space. god is a void- the void- the in-between of things. capitalism, commerce, consumption, imperialism, colonization, breaks down spaces, the in-between. it violates god. by violating human dignity, the divine grace of being able to take up space, god is also violated.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter VII. Fifth Period. — Police, Or Taxation.

3. — Disastrous and inevitable consequences of the tax. (Provisions, sumptuary laws, rural and industrial police, patents, trade-marks, etc.)

M. Chevalier addressed to himself, in July, 1843, on the subject of the tax, the following questions:

(1) Is it asked of all or by preference of a part of the nation? (2) Does the tax resemble a levy on polls, or is it exactly proportioned to the fortunes of the tax-payers? (3) Is agriculture more or less burdened than manufactures or commerce? (4) Is real estate more or less spared than personal property? (5) Is he who produces more favored than he who consumes? (6) Have our taxation laws the character of sumptuary laws?

To these various questions M. Chevalier makes the reply which I am about to quote, and which sums up all of the most philosophical considerations upon the subject which I have met:

(a) The tax affects the universality, applies to the mass, takes the nation as a whole; nevertheless, as the poor are the most numerous, it taxes them willingly, certain of collecting more. (b) By the nature of things the tax sometimes takes the form of a levy on polls, as in the case of the salt tax. (c, d, e) The treasury addresses itself to labor as well as to consumption, because in France everybody labors, to real more than to personal property, and to agriculture more than to manufactures. (f) By the same reasoning, our laws partake little of the character of sumptuary laws.

What, professor! is that all that science has taught you? The tax applies to the mass, you say; it takes the nation as a whole. Alas! we know it only too well; but it is this which is iniquitous, and which we ask you to explain. The government, when engaged in the assessment and distribution of the tax, could not have believed, did not believe, that all fortunes were equal; consequently it could not have wished, did not wish, the sums paid to be equal. Why, then, is the practice of the government always the opposite of its theory? Your opinion, if you please, on this difficult matter? Explain; justify or condemn the exchequer; take whatever course you will, provided you take some course and say something. Remember that your readers are men, and that they cannot excuse in a doctor, speaking ex cathedra, such propositions as this: as the poor are the most numerous, it taxes them willingly, certain of collecting more. No, Monsieur: numbers do not regulate the tax; the tax knows perfectly well that millions of poor added to millions of poor do not make one voter. You render the treasury odious by making it absurd, and I maintain that it is neither the one nor the other. The poor man pays more than the rich because Providence, to whom misery is odious like vice, has so ordered things that the miserable must always be the most ground down. The iniquity of the tax is the celestial scourge which drives us towards equality. God! if a professor of political economy, who was formerly an apostle, could but understand this revelation!

By the nature of things, says M. Chevalier, the tax sometimes takes the form of a levy on polls. Well, in what case is it just that the tax should take the form of a levy on polls? Is it always, or never? What is the principle of the tax? What is its object? Speak, answer.

And what instruction, pray, can we derive from the remark, scarcely worthy of quotation, that the treasury addresses itself to labor as well as to consumption, to real more than to personal property, to agriculture more than to manufactures? Of what consequence to science is this interminable recital of crude facts, if your analysis never extracts a single idea from them?

All the deductions made from consumption by taxation, rent, interest on capital, etc., enter into the general expense account and figure in the selling price, so that nearly always the consumer pays the tax: that we know. And as the goods most consumed are also those which yield the most revenue, it necessarily follows that the poorest people are the most heavily burdened: this consequence, like the first, is inevitable. Once more, then, of what importance to us are your fiscal distinctions? Whatever the classification of taxable material, as it is impossible to tax capital beyond its income, the capitalist will be always favored, while the proletaire will suffer iniquity, oppression. The trouble is not in the distribution of taxes; it is in the distribution of goods. M. Chevalier cannot be ignorant of this: why, then, does not M. Chevalier, whose word would carry more weight than that of a writer suspected of not loving the existing order, say as much?

From 1806 to 1811 (this observation, as well as the following, is M. Chevalier’s) the annual consumption of wine in Paris was one hundred and forty quarts for each individual; now it is not more than eighty-three. Abolish the tax of seven or eight cents a quart collected from the retailer, and the consumption of wine will soon rise from eighty-three quarts to one hundred and seventy-five; and the wine industry, which does not know what to do with its products, will have a market. Thanks to the duties laid upon the importation of cattle, the consumption of meat by the people has diminished in a ratio similar to that of the falling-off in the consumption of wine; and the economists have recognized with fright that the French workman does less work than the English workman, because he is not as well fed.

Out of sympathy for the laboring classes M. Chevalier would like our manufacturers to feel the goad of foreign competition a little. A reduction of the tax on woollens to the extent of twenty cents on each pair of pantaloons would leave six million dollars in the pockets of the consumers, — half enough to pay the salt tax. Four cents less in the price of a shirt would effect a saving probably sufficient to keep a force of twenty thousand men under arms.

In the last fifteen years the consumption of sugar has risen from one hundred and sixteen million pounds to two hundred and sixty million, which gives at present an average of seven pounds and three-quarters for each individual. This progress demonstrates that sugar must be classed henceforth with bread, wine, meat, wool, cotton, wood, and coal, among the articles of prime necessity. To the poor man sugar is a whole medicine-chest: would it be too much to raise the average individual consumption of this article from seven pounds and three-quarters to fifteen pounds? Abolish the tax, which is about four dollars and a half on a hundred pounds, and your consumption will double.