#natural rights

Text

Two notions of liberty revisited—or how to disentangle Liberty and Slavery

The modern liberal concept of liberty has roots in Roman law and the Roman understanding of the master and the slave. We need to unpick that heritage to imagine a better basis for our political aspirations.

David Graeber

May 19, 2013

Our idea of human freedom, with its origins in Roman law, is permeated through and through with the institution of slavery. But its links to slavery twisted the meaning of “freedom” from an empowering notion of what it is to live with dignity in a society of equals to one of mastery and control. Understanding the history of the concept should help us to regain the first and fight the second of those notions.

The meaning of the Roman word libertas changed dramatically over time. To be “free” meant, first and foremost, not to be a slave. Since slavery means above all else the annihilation of social ties and the ability to form them, freedom meant the capacity to make and maintain moral commitments to others. The English word “free,” for instance, is derived from a German root meaning “friend,” since to be free meant to be able to make friends, to keep promises, to live within a community of equals. Freed slaves in Rome became citizens—and this makes complete sense because to be free, by definition, meant to be anchored in a civic community, with all the rights and responsibilities that this entailed.

By the second century AD, however, this had begun to change. The jurists gradually redefined libertas until it became almost indistinguishable from the power of the master. It was the right to do absolutely anything, with the exception, again, of all those things one could not do. In the Digest, the basic text of Roman law, the definitions of freedom and slavery appear back to back:

Freedom is the natural faculty to do whatever one wishes that is not prevented by force or law. Slavery is an institution according to the law of nations whereby one person becomes private property (dominium) of another, contrary to nature.

Medieval commentators immediately noticed the problem here. But wouldn’t this mean that everyone is free? After all, even slaves are free to do absolutely anything they’re actually permitted to do. To say a slave is free (except insofar as he isn’t) is a bit like saying the earth is square (except insofar as it is round), or that the sun is blue (except insofar as it is yellow), or, again, that we have an absolute right to do anything we wish with our chainsaw (except those things that we can’t).

In fact, the definition introduces all sorts of complications. If freedom is natural, then surely slavery is unnatural, but if freedom and slavery are just matters of degree, then, logically, would not all restrictions on freedom be to some degree unnatural? Would not that imply that society, social rules, in fact even property rights, are unnatural as well? This is precisely what many Roman jurists did conclude—that is, when they did venture to comment on such abstract matters, which was only rarely. Originally, human beings lived in a state of nature where all things were held in common; it was war that first divided up the world, and the resultant “law of nations,” the common usages of mankind that regulate such matters as conquest, slavery, treaties, and borders, that was first responsible for inequalities of property as well.

This in turn meant that there was no intrinsic difference between private property and political power—at least, insofar as that power was based in violence. Dominium, a word derived from dominus, meaning “master,” or “slave-owner,” is the term in Roman law that means absolute private property. It is the sort of property-right that today has been theorised as the model case of a “negative freedom”—that which you can do with no interference from anyone else.

As time went on, Roman emperors also began claiming something like dominium, insisting that within their dominions, they had absolute freedom—in fact, that they were not bound by laws. At the same time, Roman society shifted from a republic of slave-holders to arrangements that increasingly resembled later feudal Europe, with magnates on their great estates surrounded by dependent peasants, debt servants, and an endless variety of slaves—with whom they could largely do as they pleased. The barbarian invasions that overthrew the empire merely formalized the situation, largely eliminating chattel slavery, but at the same time introducing the notion that the noble classes were descendants of the Germanic conquerors, and that the common people were inherently subservient.

Still, even in this new Medieval world, the old Roman concept of freedom remained. Freedom was simply power. When Medieval political theorists spoke of “liberty,” they were normally referring to a lord’s right to do whatever he wanted within his own domains—his dominium. This was, again, usually assumed to be not something originally established by agreement, but a mere fact of conquest: one famous English legend holds that when, around 1290, King Edward I asked his lords to produce documents to demonstrate by what right they held their franchises (or “liberties”), the Earl Warenne presented the king only with his rusty is sword. Like Roman dominium, it was less a right than a power, and a power exercised first and foremost over people—which is why in the Middle Ages it was common to speak of the “liberty of the gallows,” meaning a lord’s right to maintain his own private place of execution.

By the time Roman law began to be recovered and modernized in the twelfth century, the term dominium posed a particular problem, since, in ordinary church Latin of the time, it had come to be used equally for “lordship” and “private property.” Medieval jurists spent a great deal of time and argument establishing whether there was indeed a difference between the two. It was a particularly thorny problem because, if property rights really were, as the Digest insisted, a form of absolute power, it was very difficult to see how anyone could have it but a king—or even, for certain jurists, God.

This genealogy of liberty allows us to understand precisely how Liberals like Adam Smith were able to imagine the world the way they did. This is a tradition that assumes that liberty is essentially the right to do what one likes with one’s own property. In fact, not only does it make property a right, it treats rights themselves as a form of property. In a way, this is the greatest paradox of all. We are so used to the idea of “having” rights—that rights are something one can possess—that we rarely think about what this might actually mean. In fact (as Medieval jurists were well aware), one man’s right is simply another’s obligation. My right to free speech is others’ obligation not to punish me for speaking; my right to a trial by a jury of my peers is the responsibility of the government to maintain a system of jury duty. The problem is just the same as it was with property rights: when we are talking about obligations owed by everyone in the entire world, it’s difficult to think about it that way. It’s much easier to speak of “having” rights and freedoms. Still, if freedom is basically our right to own things, or to treat things as if we own them, then what would it mean to “own” a freedom—wouldn’t it have to mean that our right to own property is itself a form of property? That does seem unnecessarily convoluted. What possible reason would one have to want to define it this way?

Historically, there is a simple—if somewhat disturbing—answer to this. Those who have argued that we are the natural owners of our rights and liberties have been mainly interested in asserting that we should be free to give them away, or even to sell them.

Modern ideas of rights and liberties are derived from what came to be known as “natural rights theory”—from the time when Jean Gerson, Rector of the University of Paris, began to lay them out around 1400, building on Roman law concepts. As Richard Tuck, the premier historian of such ideas, has long noted, it is one of the great ironies of history that this was always a body of theory embraced not by the progressives of that time, but by conservatives. “‘For a Gersonian, liberty was property and could be exchanged in the same Way and in the same terms as any other property’—sold, swapped, loaned, or otherwise voluntarily surrendered.” It followed that there could be nothing intrinsically wrong with, say, debt peonage, or even slavery. And this is exactly what natural-rights theorists came to assert. In fact, over the next centuries, these ideas came to be developed above all in Antwerp and Lisbon, cities at the very center of the emerging slave trade. After all, they argued, we don’t really know what’s going on in the lands behind places like Calabar, from which so many men and women were being enslaved and shipped to the Americas, but there is no intrinsic reason to assume that the vast majority of the human cargo conveyed to European ships had not sold themselves, or been disposed of by their legal guardians, or lost their liberty in some other perfectly legitimate fashion. No doubt some had not, but abuses will exist in any system. The important thing was that there was nothing inherently unnatural or illegitimate about the idea that freedom could be sold.

Before long, similar arguments came to be employed to justify the absolute power of the state. Thomas Hobbes was the first to really develop this argument in the seventeenth century, but it soon became commonplace. Government was essentially a contract, a kind of business arrangement, whereby citizens had voluntarily given up some of their natural liberties to the sovereign. Finally, similar ideas have become the basis of that most basic, dominant institution of our present economic life: wage labor, which is, effectively, the renting of our freedom in the same way that slavery can be conceived as its sale.

It’s not only our freedoms that we own; the same logic has come to be applied even to our own bodies, which are treated, in such formulations, as really no different than houses, cars, or furniture. We own ourselves, therefore outsiders have no right to trespass on us.

This might seem an innocuous, even a positive notion, but it looks rather different when we take into consideration the Roman tradition of property on which it is based. To say that we own ourselves is, oddly enough, to cast ourselves as both master and slave simultaneously. “We” are both owners (exerting absolute power over our property), and yet somehow, at the same time, the things being owned (being the object of absolute power).

The ancient Roman household, far from having been forgotten in the mists of history, is preserved in our most basic conception of ourselves—and, once again, just as in property law, the result is so strangely incoherent that it spins off into endless paradoxes the moment one tries to figure out what it would actually mean in practice. Just as lawyers have spent a thousand years trying to make sense of Roman property concepts, so have philosophers spent centuries trying to understand how it could be possible for us to have a relation of domination over ourselves. The most popular solution—to say that each of us has something called a “mind” and that this is completely separate from something else, which we can call “the body,” and that the first thing holds natural dominion over the second—flies in the face of just about everything we now know about cognitive science. It’s obviously untrue, but we continue to hold onto it anyway, for the simple reason that none of our everyday assumptions about property, law, and freedom would make any sense without it.

To understand the history and, ultimately, incoherence of the notions of liberty grounded in Roman notions of dominion is to potentially free ourselves to re-imagine liberty. For example, to recognise the forgotten “obligations owed everyone in the entire world” inherent in our freedoms; but also to resurrect the older notion of liberty as the state achieved by citizens acting together in determination of a common good.

#repost of someone else’s content#graeber#history#ancient Rome#medieval Europe#slavery#mind-body dualism#racism#antiblackness#liberals#liberalism#classical liberalism#capitalism#private property#social contract#natural rights#consent of the governed#anarchism

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

spot the difference

#john locke#borzoi#borzoi dog#natural rights#enlightenment#history#philosophy#freaky#he has such pretty eyes#cutie w a bootie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

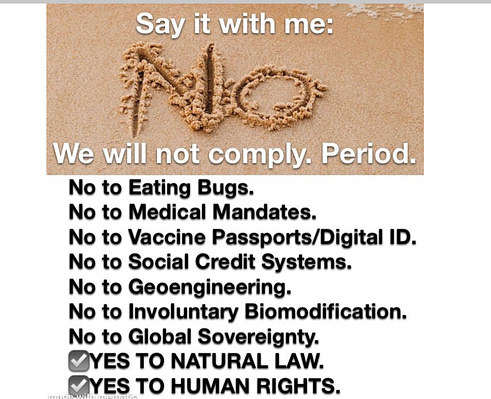

It's simple, really.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Natural Rights of Transgender Americans

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. To these three rights the Declaration our Forefathers sent to Great Britain entitles all of us. Yet what do we see in our laws? What do we see our congressmen writing?

In Florida, a state not of the first 13 but whose people are entitled to their natural rights nonetheless, there is a bill (FL Senate Bill 254) calling for children to be taken from parents that would support them if they were transgender. This bill strikes at all of these rights at once, as do bills like it.

Do not these children deserve to live? Reuters wrote seven years ago in May of 2016 that likelihood of suicide in the transgender community increases with rejection and lack of support. This bill drives them directly to suicide and substance abuse, straight to death.

Do not these children deserve liberty? Do they not deserve the right to choose who they are, and how they will act and present themselves in a welcoming environment?

Do not these children deserve happiness, or at least the pursuit of it?

Perhaps you believe that restrictions on gender-affirming care for minors is reasonable, but what about adults? In January of this year, a bill was put forth in Oklahoma that would completely ban gender-affirming care for those under 26 years of age (OK Senate Bill 129). While the bill was later revised to limit it to 18 years old (OK Senate Bill 613), the fact it was 26 in the first place shows that just banning gender affirming care for minors is not enough.

In the same state, laws were passed restricting the usage of public restrooms, not allowing transgender people to use the correct restroom.

In the case of all legislation that restricts care for transgender people in any state, I beg you to ask the questions:

Do not these people deserve the right to live?

Do not these people deserve the right to liberty?

Do not these people deserve the right to pursue happiness?

Do not these people deserve the American Dream?

#politics#us politics#us#america#trans rights#transgender#trans genocide#lgbtq#writing#human rights#natural rights#government#governance#essay

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#immanuel kant#kant#kantianism#philosophy memes#philosophy#philosophy meme#deontology#deontological ethics#political philosophy#legal philosophy#natural rights#social contract#classical liberalism#libertarianism#minarchism

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

having a child has taught me that every toddler is completely justified in their frustrations and tantrums because learning how to do something you have literally never encountered or heard of before is insane. and being expected to be completely calm in the face of this constant barrage of overwhelming information is doubly insane.

i got charlie a sticker activity book and it occurred to me i have to TEACH someone how to unpeel stickers. it's SKILL that requires DEXTERITY and FINE MOTOR ABILITY. i thought it was obvious that you have to curl the page a little bit to create a break in the cut so the sticker comes up.

obviously a fucking BABY wouldn't know that because they have no background experience to inform their thought process. OBVIOUSLY. and OBVIOUSLY the LITERAL BABY wouldn't get it right the first few times. it would OBVIOUSLY take practice. lots of it.

i hate this feeling. it's so obvious. why are children treated so badly when they're learning everything for the first fucking time. why do people treat children so horribly and expect so much. they're brand new. why didn't i get the same grace i give to my child? why did no one have patience for me? why, when it's this easy?

it's so easy. it's so fucking easy.

#ok2rb#op#babbyposting#apologizing to my child is second nature#i'm brand new at it too#obviously im gonna fuck up here and there#its only right to apologize#why did no one ever apologize to me#not until it was too late

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

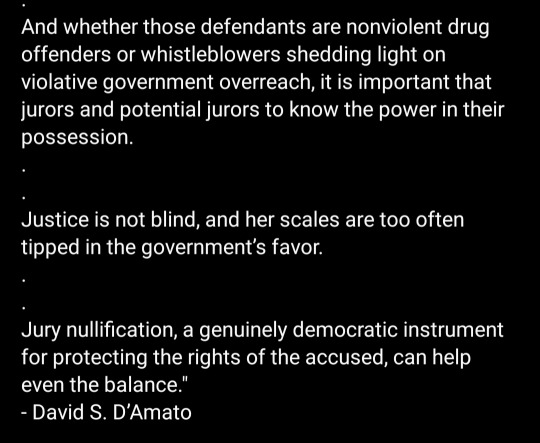

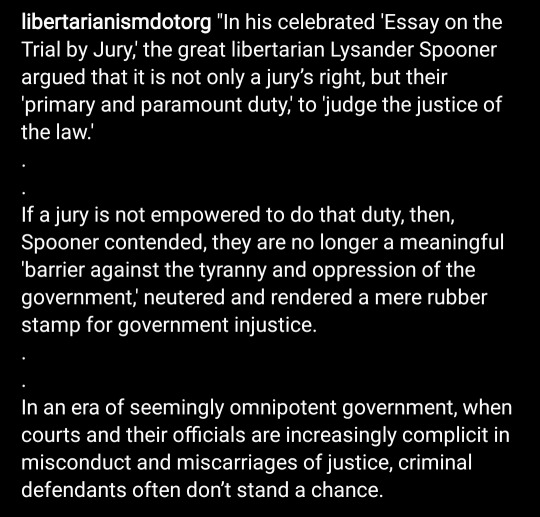

Justifications for Human Rights: Natural Rights

This is Gensuke. I will break down the idea of natural rights in this post.

My main claim is that natural rights are the main core in human rights.

Natural rights are rights to life, liberty, and property. People possess these fundamental rights when they are born.

This idea of natural rights originated in ancient Greek era. Philosophers like Aristotle claimed that human beings possess natural rights before nations. He added that governments are obligated to protect citizens natural rights.

In the 17th century, an English philosopher named John Locke contributed in deepening the understanding of human rights. In his books he claimed the following three things about natural rights.

Humans have rights to life, liberty, and property before any political institution

Governments are created to protect citizens natural rights

When natural rights are not protected by governments, citizens have the right to overthrow that government.

There are evidences to prove that the basic ideas of human rights originate from natural rights.

Evidence 1: The Declaration of Independence

“ We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. “

Jefferson suggests that people have the fundamental rights (rights to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness). These rights are fundamental for human rights.

Evidence 2: Universal Declaration of Human Rights (General Assembly Resolution)

Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Although this is a resolution from the General Assembly, every human rights treaty mentions the UDHR in their preamble. This suggests that natural rights are the foundations of human rights.

-Gensuke

0 notes

Text

Dismissiveness as a Natural Right

TO BE dismissive may seem like an insolent and uncharitable character trait among persons who reject the advances of a self-described prophet or religious figure. Many Catholics, for instance, will reject and dismiss the political opinions of the Pope, especially if those opinions are meant to appease politically correct automatons. Moreover, such dissenting Catholics have a right to reject any…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Natural Law as a Restraint Against Tyranny | Judge Andrew P. Napolitano

We have a persumption of Liberty.

0 notes

Text

the idea of natural rights is very not accurate. humans arent “born with rights” thats literal idealism. the ideas of human rights are developed through societal interaction and development. and because they are an aspect of human social interaction, they change and develop from and in relation to their mode of production and the conditions of class struggle. the current dominant one is capitalism, and as the ideas of the ruling class are the most dominant ideas in every epoch, private property and the right to exploitation with it are seen as human rights.

0 notes

Text

CONTRACT VS. COMPACT

This posting is a short follow up to the last posting, “Spending and Saving.” In that prior posting, a simple economic factor was pointed out and related to what government’s role should be in the economy. Here is not a restatement of that relationship, but a further analysis of a point that posting made. That is, that the construct, parochial/traditional federalism, a dominant view that Americans shared in the years before World War II, was inadequate for the more modern times of American governance and politics.

In this clarification, the term parochial is central. To cite Wikipedia, one finds the following:

Parochialism is the state of mind whereby one focuses on small sections of an issue rather than considering its wider context. More generally, it consists of being narrow in scope. In that respect, it is a synonym of "provincialism". It may, particularly when used pejoratively, be contrasted to cosmopolitanism.[1]

It is a term this blogger originally was introduced to in his growing up years within the Catholic tradition.

He went to parochial schools for 13 years. What little questioning he expressed at the time solicited a sense that parochialism referred to the local church and local concerns – much in line with what Wikipedia states. What he was to learn and appreciate was how central this idea was to American culture until, as the last posting pointed out, the realities of a national and now global economy made this provincialism untenable.

It particularly applies to views of governance and politics in the US, since for various reasons, localism was held to be central to the American experience. The federalism that grew in the US was originally based on the local settlements that sprung up on the eastern seacoast of the North American landmass. Each was the product of settlers joining together and formulating a polity based on what was considered a sacred agreement. The word, compacts, applies to these agreements.

More specifically, as Daniel Elazar explains, these agreements were a type of compact, that being covenants.[2] In that they resembled Judeo tradition, covenants established a union in which whatever members did, they were part of that union. The signees of the agreement called on God to witness the agreement which solemnized it.

As the American people became a bit more secular – to a degree the product of the Enlightenment – this element was put aside, making the newer agreements straightforward compacts. A comparison that illustrates this turn is that the Declaration of Independence (1776) is a covenant, and the US Constitution (1787) is simply a compact. In both cases, the purpose was to hold those agreements in solemnity.

The distinctions one can make between or among the founding documents (including, for example, state constitutions) and the terms one uses to classify them have consequences. And to illustrate, a legal matter comes to mind. To further distinguish what is being described in this posting, it introduces yet another term, that being contract. Here, a historical turn – an unfortunate one – muddles the waters. And sure enough, the French have a role. No, French influence is not at odds with fortune, but in terms of constitutional principles, it does have another tradition.

The origins of this difference can be traced to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and how he envisioned the ways and reasons people organized to form polities. In doing so, they give up some natural rights – the ability to behave as they wish – to practically allow them to live under a set of laws or restrictions. This language casts a different sense from what the Judeo tradition called for.

With a social contract, one deals with a quid pro quo – something for something (personal rights for societal arrangement). This stands in distinction to a more communal sense of the Judeo model. But if applied to the Constitution, it casts that agreement with a more contractual sense and diminishes its compact-al or communal orientation.

On a practical level, for example, with a social contract – the more contractual approach – the courts, usually at the hands of conservative jurists, have elected to interpret the Constitution and laws in a literal fashion, like one interprets a contract. This is called textualism. It holds other ways to interpret – such as historically, traditionally, structurally, prudentially, morally or based on precedent – as being illegitimate to some degree.

In this singular way, one can see how this other view – the natural rights view – has drained, from the American experience, the bonding force of a communal constitutional framework. The consequences have been numerous and have most recently included the palpable sense of a politically polarized citizenry. As the last posting concluded, a form of federalism – a compact approach – would benefit the American people by reintroducing a more communal sense – with hopefully less parochialism – to its constitutional view.

[1] See “Parochialism,” Wikipedia (n.d.), accessed January 9, 2024, URL: Parochialism - Wikipedia.

[2] This blog has repeatedly cited Elazar. For a more recent citing, see “Compact Theory of the U.S. Constitution,” Center for the Study of Federalism (n.d.), accessed January 9, 2024, URL: https://encyclopedia.federalism.org/index.php/Compact_Theory_of_the_U.S._Constitution.

#parochial#provincial#federalism#compact#contract#textualism#natural rights#civics education#social studies

0 notes

Text

If you aren't following the news here in the Pacific Northwest, this is a very, very big deal. Our native salmon numbers have been plummeting over the past century and change. First it was due to overfishing by commercial canneries, then the dams went in and slowed the rivers down and blocked the salmons' migratory paths. More recently climate change is warming the water even more than the slower river flows have, and salmon can easily die of overheating in temperatures we would consider comfortable.

Removing the dams will allow the Klamath River and its tributaries to return to their natural states, making them more hospitable to salmon and other native wildlife (the reservoirs created by the dams were full of non-native fish stocked there over the years.) Not only will this help the salmon thrive, but it makes the entire ecosystem in the region more resilient. The nutrients that salmon bring back from their years in the ocean, stored within their flesh and bones, works its way through the surrounding forest and can be traced in plants several miles from the river.

This is also a victory for the Yurok, Karuk, and other indigenous people who have relied on the Klamath for many generations. The salmon aren't just a crucial source of food, but also deeply ingrained in indigenous cultures. It's a small step toward righting one of the many wrongs that indigenous people in the Americas have suffered for centuries.

#salmon#dam removal#fish#animals#wildlife#dams#Klamath River#Klamath dams#restoration ecology#indigenous rights#Yurok Tribe#Karuk Tribe#nature#ecology#environment#conservation#PNW#Pacific Northwest

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

HETEROSEXUAL CIS-PEOPLE LOOK HERE

Snaps my fingers at you as you scroll past this post

Look at me. Listen.

I'm not the best at serious posts, but that article up there reminded me of how important it is that people like you stand up for us. So hold on while I try to get this out of my mushy end-of-work-day brain.

We could fight this fight ourselves for decades trying to reach the equal laws, gender affirming trans healthcare that doesn't have a 2-5+ soul-eating years of waiting time, medical care with equal knowledge of lgbtqia+ bodies, and, what is often forgotten, inclusion in the little everyday areas of life like our way of speaking or things being set up or designed with the existence of queer people in mind.

But you joining in could get us there so much faster.

The power you have as a hetero cis person is that you set the standard for what is seen as the average way of treating us among other hetero cis people. You have been given the power of deciding what's "normal" and I'm begging you to use it.

Richard Green is a great example of to what extent your actions can help our situation, and smaller ways of support still add up to a great impact on society, and could make the days of the queer people you interact with.

Educate yourself before you speak up, but don't be silent.

#lgbtqia+#lgbtq#lgbtqia#lgbtq+#lgbtqia+ rights#lgbtq+ rights#lgbtq rights#interesting#article#psychology#mental health#psychologist#reading#culture#cooking#drawing#music#nature#science#baking#pets#inspirational#gaming#photography#fashion#writing

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘥𝘳𝘪𝘷𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘢 𝘧𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵

ig credit: mckennawest.travel

#what i need to be doing right now lol#autumn#fall#nature#trees#forest#mountains#naturecore#aesthetic#photography#cottagecore#scenery#october#moodboard#plants

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

let her go

#homestuck#vriska serket#terezi pyrope#vriska#terezi#vrisrezi#mic_art#screencap redraw of that one utena scene woohoo#vrisrezi and utenanthy dont share many similarities but there are some interesting parallels that can be drawn#like theyre all characters who are devoted to the respective roles they think they have#utena needs to be a prince and vriska needs to be a hero#terezi needs to cast vriska as the villain so that she can be the one to bring her to justice while anthy#is resigned to her role as the rose bride and is cast as a witch by others (and herself in a way...) to justify her suffering#im too tired to put into words all the other shit rattlign around in my brain but something something vriska society violence princes utena#something interesting to note is that in the rgu stabbing scene utena is walking to the left while is hs vriskas walking to the right#which i think is mostly a cultural difference due to english being read left to right while japanese is read right to left#changing which direction is percieved as forward#which could be read further into but could also just be the natural flow of the scene or whateevr#idk i need to peruse ohtori.nu again i looooove reading utena essays

2K notes

·

View notes