#black marxism

Text

#capitalism#uploads#offscreendeathshots#south side#south side hbo#hbo max#corporatism#david graeber#karl marx#marxism#black marxism#anticapitalism

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition by Cedric J. Robinson

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cedric Robinson by. Joshua Myers

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Global popular unity"

Artwork of a comrade in China

Via Nadezhda Sablina

#communist#socialism#revolution#workers#internationalism#intersectionality#class struggle#youth#women#transgender#LGBTQ#FreePalestine#Black Liberation#Marxism#China#artists

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

revolutionary women’s art.

Panther Rally flyer from a Boston women’s liberation front

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Join Our International Youth Activist Discord Server! 🌎✨

Looking for an incredible space to connect with like-minded youth activists from around the world? Look no further! Welcome to our amazing Better Future Program, Inc. (BFP) server, created by our passionate youth volunteers in April 2021. Here, we forge friendships, ignite ideas, and embrace the collective power of youth!

📚 Free Resources: Dive into our extensive Liberation Library, with over 3,000 resources covering social justice, mental health, and academia. It's a treasure trove of knowledge and inspiration for activists of all backgrounds. Explore it here: Liberation Library.

🫱🏽🫲🏾 Peer Support: We understand the importance of having a supportive community. Our server provides a space for peer support, where you can share what's going on in your life, receive a listening ear, or seek advice. We're here for you! Read our peer support policy.

🌎 International Community: Connect with fellow activists from all corners of the globe. Our server brings together passionate individuals who share a commitment to creating a better future. Join us and be part of our worldwide family!

📋 Channel Highlights: Check out our various channels, each serving a unique purpose. From silly questions of the day and history lessons to political discussions and private identity-based chats, there's something for everyone. And if you don't see what you want? Just submit a suggestion!

✨ Additional Info: Don't miss our weekly plenary meetings, held on Sundays, where we discuss organizational updates, next steps, and engage in political education. Zoom link in our Discord! Keep an eye on the #announcements channel for the latest details.

Ready to Join?

Click the link below to dive into our vibrant community: Discord Server

Volunteer with Us!

If you're interested in becoming part of our dedicated team, check out our volunteer application: Volunteer Application

🌟 Spread the Word! 🌟

Share this post with your friends who are passionate about activism. Together, we can build a better future for all.

Let's make a difference, one step at a time. See you in the server!

#pinned post#reaux speaks#discord server#social justice#activism#abolition#anarchism#socialism#communism#marxism#leftist#intersectional feminism#palestine#black lives matter#stop asian hâte#anti capitalism#disability justice#neurodivergent#queer#trans#acab#foster care#mad liberation#free palestine#israel

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Critique of the Western Left

The Western Left has been marred by infighting in recent years, effectively crippling any capacity it has to fight back against the vicious capitalist system it rightfully opposes.

In my eyes, I see two main contributing factors to the general incompetency of the Left in the Western world. Infighting and ineffective campaigning.

Infighting between sects within the left along niche ideological lines stunts its ability to grow its membership and influence by making the movement look irrelevant, hostile, and elitist. The right isn't divided along small ideological lines. They can and will cooperate to spread their collective hateful ideologies. To combat this effectively, we need to put our differences aside and unite along our common enemy: the capitalist system. Only when the abolition of capitalism has been undertaken can we afford to disagree on minor policy and theoretical differences.

Secondly, Leftist campaigning is so focused on ideological niches that it no longer appeals to the working people. The average worker is not concerned about who Gonzalo was. They are too busy worrying about food, about rent, about utilities and education, and safety. We need to campaign issues that are affecting the people the most. We NEED to appeal to the masses and embrace left-wing populism to garner the popular support needed to oppose fascism if we want any chance of facilitating positive and lasting change.

We have a common enemy, and we must not fight each other. Instead, we must work together for the good of the people and for the good of the planet.

#anarchism#anarchocommunism#communism#cops#current events#gaza#gaza solidarity encampment#genocide#history#antifascism#antifascist#antifascismo#antifaschistische aktion#leftism#left wing#socialist revolution#columbia university#divestment#marxism#unity#palestinian liberation#black liberation#trans liberation#womens liberation#protest#ecosocialism#palestine#progressive politics#essay#blog

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under capitalism, the inequality of women stems from exploitation of the working class by the capitalist class. But the exploitation of women cuts across class lines and affects all women. Marxism-Leninism views the woman question as a special question which derives from the economic dependence of women upon men. This economic dependence as Engels wrote over 100 years ago, carries with it the sexual exploitation of women, the placing of woman in the modern bourgeois family, as the “proletariat” of the man, who assumes the role of “bourgeoisie.”

Hence, Marxist-Leninists fight to free woman of household drudgery, they fight to win equality for women in all spheres; they recognize that one cannot adequately deal with the woman question or win women for progressive participation unless one takes up the special problems, needs and aspirations of women – as women.

—Claudia Jones, "We Seek Full Equality for Women".

#claudia jones#we seek full equality for women#marxism leninism#socialist feminism#black feminism#womanism#radical feminism#feminism#capitalism#marxism

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome!

QueerPunkTomatoes is a reference to guerilla gardening, because food should be free. It isn't that deep! All people should have food! You shouldn't have to earn it!

AL, (any/no pronouns), 20. Sociology student. Queer. Fat. Disabled. Trans.

This blog is pro-marginalized liberation and anti-capitalism.

Just don't be a dick and we'll be friends! 🫡

Also I'm very passionate about social justice and I get angry but I'm actually a very friendly person!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I love my mutuals and you should come say hi :)

Recovering from an abusive childhood and an eating disorder while desperately searching for community 💜

(want to start a timebank with me? pretty please :))

#solarpunk#anti-capitalism#solar punk#marxist feminism#cripple punk#eat the rich#communism#marxism#marxist#karl marx#queer liberation#fat liberation#trans liberation#black liberation#palestinian liberation#indiginous liberation#Liberation#Punk#anti capitalism#anti imperialism#anticapitalism#trans lives matter#black lives matter#sociology student#social justice#communist#disabled#free gaza#liberation#lgbtqia

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Class Solidarity Flag

Alternate name: Class Consciousness Flag

Credits:

- Conglomerate flag: Myself

- Colours: 1871 Paris Commune (Red), 1917 October Revolution (Red, Yellow), Spanish Civil War (socialist) Republicans (Red, Black), USSR (Red, Yellow)

- Crossed arms: Sándor Pinczehelyi, "Hammer and Sickle"

- Fist stylization: Black power fist

- Yellow star: USSR, various socialist and communist groups

- Book outline: Adobe Stock photos

Image description:

A black flag with a 1 to 2 ratio. In the centre are two red crossed fists at the wrists in solidarity, with an inverted, yellow, five-point star at the wrist junction. Above the crossed fists is an open red book.

Symbolism breakdown:

In basic symbolism, the black and red colours represent Communism, liberation, and leftist ideology. The black may also be used to represent Anarchism.

This flag also uses the colour red and crossed fists to represent solidarity between different oppressed classes (e.g. black people, lower class workers, queer people, trans people, disabled people, etc.), and also uses the colour black to represent the sacrifices of people fighting for class liberation.

The star is used to represent humanity's solidarity under the Sun/Sol, as well as Polaris/The North Star, extending the scope of solidarity beyond nationalism to a full human scale.

The open book is used to represent the importance of education, especially in law, to help liberate oppressed classes.

This flag is intended to be flown above or beside other flags of oppressed classes (e.g. pride flags, the black power flag, the Communist flag, the Palestine flag, etc.), but may be flown alone to express solidarity or in times of class struggle.

#communism#communist#socialism#socialist#marxism#marxist#anarchism#anarchist#leftism#leftist#politics#global politics#world politics#black power#lgbt#lgbtq#queer#trans#gay#lesbian#feminism#feminist#palestine

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Alta Ifland

Published: Mar 25, 2024

Most of us have had at least once in a lifetime the experience of paradise when a place seems suddenly transfigured and elevated to an otherworldly realm. I experienced paradise in Iceland’s Reykjavik Airport in September 1991, where the plane that took me as a political refugee from Romania to the United States stopped for a couple of hours for a layover. It was the first time I had left my country of birth, and Reykjavik’s airport was my first contact with the West. I remember entering spaces that made me think of Aladdin’s cave of wonders, where under transparent glass lay mesmerizing diamond necklaces, and gorgeous saleswomen with seducing smiles inviting me to try them on; and I remember the impeccable marble-white restrooms like an alien spaceship with curious buttons I had no idea how to maneuver. Everything was clean, as if under the care of a doting fairy, and everybody smiled quietly as if life was a streak of uninterrupted joy.

I went back to Reykjavik for a literary conference twenty years later, but I could no longer find paradise. The diamond necklaces had no sparkle, Aladdin’s cave turned out to be a banal store, the women were like everywhere else, and the toilets nothing to write home about. The gap between the two experiences paralleled my first encounter with JFK Airport in New York, where—having to wait for my connecting flight to Jacksonville, Florida—I wandered for several hours among a hustle and bustle of people, stores, restaurants, buses and taxis, convinced that I was exploring the city itself. I mean, who in their right mind would imagine that they could find all of the above in an airport? It was only years later when I returned to New York that I realized that all I had seen of the city was, in fact, the airport.

These two primal encounters have left me with a lifelong love of airports, although life post-9/11 has considerably altered the experience. But the impression that our existence is made of two irreconcilable universes remained for a long time until, roughly, the advent of social media, which managed to unite the two into one indistinguishable blur and a chorus of mingled, screaming voices. Having spent my life between different worlds, I’m fascinated by the different frameworks people can place around the same events, according to the point of view given to them by their location in time and space.

As newly-arrived immigrants, my then-husband and I naturally gravitated toward other immigrants from Eastern Europe, and since they often went to church—which was, anyhow, the only socializing venue in Jacksonville (a city immortalized by Henry Miller in The Air-Conditioned Nightmare as a soul-killing locale)—we found ourselves for two years in the strange company of puritan evangelicals. After this edifying experience, my admission to an M.A. program at the University of Florida threw me into an environment that seemed completely opposite to the previous one, as if America were made of two separate worlds with two different types of people. Both types were a shock because they didn’t resemble the Americans I had known from the movies I’d seen—neither the neighbors who asked our Romanian friends to cover the non-existent breasts of their five-year-old daughter at the pool, nor my professors from the English department who joyfully professed their Communist and Marxist convictions to a roomful of sympathetic ears.

I cannot forget one professor who praised Mao’s “cultural revolution”—to this day I have no idea whether he was aware that millions had died as a result of this “revolution,” and that many Chinese in rural areas were so starved that they ate their own children.

It was clear to me that these academics knew nothing about the world I came from, which was, again, shocking, given that I knew a lot more about their world even though the country I grew up in was so isolated from the West that we used to refer to it as “outside.” I was the one who grew up in a prison, yet it was American academics who were the ignorant ones.

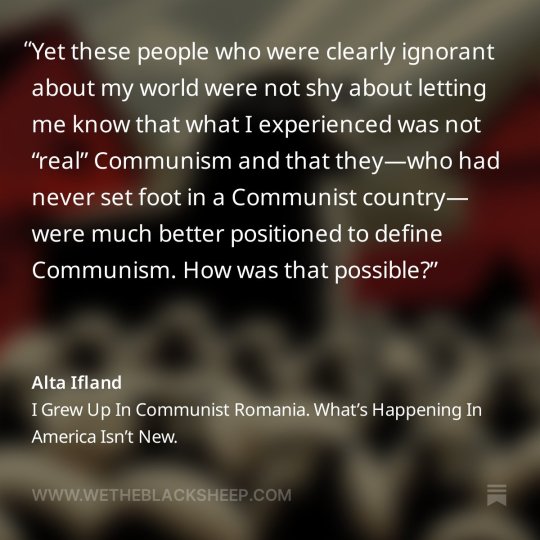

Growing up in Communist Romania, I read many American classics (the first book I read at eight years old was Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) and watched countless American movies. On the other hand, my American counterparts never read any books by Romanians (though I am not arrogant enough to demand that) or by Eastern Europeans generally, and rarely watched any European movies, let alone Eastern European movies. Yet these people who were clearly ignorant about my world were not shy about letting me know that what I experienced was not “real” Communism and that they—who had never set foot in a Communist country—were much better positioned to define Communism. How was that possible?

Let me tell you what nobody teaches Americans about the part of the world I come from.

--

For years, whenever I drove on one of America’s ten-lane highways, it felt impossible that this world existed in the same historical era as the world of my grandparents. I don’t have any photos of my paternal grandparents because in Communist Romania very few of us owned cameras. But they have remained etched in my mind in a way that makes them immortal, eternally old, as if their dark faces had always been crossed by deep ridges—the kind of faces only Indians (as we called them back then) had in black and white Hollywood movies, their feet always bare and so thick with calluses that when they washed them at night you could see the solidified dirt like mortar between brick-like layers of skin. They never used soap yet they had a drawer full of it, every single piece sent or brought by my father from the city. For them, soap was the equivalent of expensive jewelry, which Grandmother occasionally showed me, opening the drawer with pride: “See? Your father sent them. I keep them all.”

My grandparents lived in a world in which there was no money—I mean, there was no exchange of money, save for the rare occasions when Father gave them a few coins to buy bread. I remember walking with Grandfather unending kilometers through a sea of yellow corn until we reemerged in the world of the living, and Grandfather took out a handkerchief with a complicated knot that he untied to free the coins in exchange for the loaf of bread handed to him by the store clerk at the edge of the cornfield. But this type of exchange happened rarely. Usually, we ate hard polenta, the default everyday meal of Romanian peasants. We ate it either as a substitute for bread, which my grandparents usually couldn’t afford, or else as a meal immersed in a bowl of milk, one bowl for the entire table, inside of which our spoons often met, clanking.

My grandparents lived in the same way their ancestors had for generations in that part of the world: the province of Oltenia in Southern Romania. The only thing that had changed was that they were no longer periodically invaded by the Turks. The stove Grandmother used for cooking was like none other I’d seen except in films about remote indigenous populations—an oval-shaped structure of whitewashed clay set on the ground, with an opening through which one could glimpse the burning twigs, and atop, simmering pots full of aromatic dishes. In front of the stove, wearing her long Gypsy-like dress and stirring the pots, was seated Grandmother on a tiny chair, it too from a different world—about twenty inches high, with only three legs.

My grandparents’ village is where I spent my summers until I finished high school. During the school year, I lived with my parents in a small town in Transylvania in one of the countless intensely ugly Soviet-style flats. The grade school I went to was five minutes away on foot—since first grade, we all went on foot everywhere, unsupervised, and had the apartment key tied on a cord around our neck (apparently, today’s Romanians call us “the generation with the key by the neck”). Needless to say, we came back home on our own, warmed up the food prepared by our mothers, and were responsible for the supervision of our younger siblings until our parents came home from work.

My classmates were mostly children of factory workers and public office clerks; many of these parents had never finished high school and those with university diplomas were rare. Under Communism there was almost no middle class, and for a simple reason: the majority of people who had been part of it (university professors, politicians, economists, sociologists, priests, artists, writers, journalists, etc.) had been imprisoned, tortured and murdered.

Their guilt? They were all “enemies of the people,” the “people” being defined as dirt-poor peasants and what Marx called “the “proletariat.” Neither of my parents had college degrees. My father, whose parents were illiterate, never read a book; my mother, whose father was a chiabur (a farmer who paid for the sin of once owning land by spending a year in prison and having his eldest daughter refused admission to high school), used to read and over the years acquired a small library of Romanian, French, and English classics which I read dozens of times. After I finished reading our library, I began to explore the local libraries. With my best friend, whose parents were construction workers and morbid alcoholics, we took weekly trips to a library where the books were so yellowed and old they fell apart, and returned with a huge travel bag full of books. Without any guidance, we discovered many of the great classics: Sartre, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Cervantes, Gide, Flaubert, Zweig, Twain, Dickens—we read them all, entirely unaware that they were “great writers,” because no one had lectured us on their greatness. In our isolated world, we had a great advantage over children growing up in Western countries: we could discover the world with our own minds and in our own words.

When I say we had an “advantage,” don’t imagine that I'm glorifying the “system” in which we grew up. The world in which we were reading these books had the following characteristics: long lines to buy anything, major food items (sugar, oil, coffee, flour, butter) rationed and hard to find, hygiene products (soap, feminine products, toothpaste) entirely absent, winters without heat spent with our coats on inside our homes, electricity two hours a day, a single TV channel with most of its programs being delirious political propaganda, water cut off for days and sometimes weeks. In order to survive most city dwellers had to use the black market, where you could buy a pair of jeans for the cost of a monthly salary. For reference, my parents’ incomes combined totaled about eighty dollars per month.

In school we studied French. Without anyone’s exhortation and only the help of a dictionary, I soon began to read French classics for my own pleasure: Mérimée, Gide, Zola, Martin du Gard, Dumas, everything I could find. I was the best student in my grade in French, so I decided to major in it. In order to be admitted to college one needed to pass a very difficult exam in one’s specialty, and there were only about twenty positions for French students per university with just a handful of universities in the entire country. The majority of applicants able to pass the exam were either children of university professors or students from preparatory high schools. Given these circumstances, my teachers, neighbors, and parents all insisted that I should study engineering like everybody else and told me I was crazy to even consider French. Yet I persisted and passed the exam with the highest possible grade. While in college, during an internship where I worked as an assistant French teacher in a high school, I attended a class where the lead teacher introduced French food to the students, and after several minutes of hearing descriptions of baguettes, brie, camembert, and the like, one of them fainted. For us, this food was like fiction—not only had we never tasted it, we couldn’t even imagine that we would ever see it outside of a book. We were hungry and cold all the time, yet whenever we’d turn on the TV all we'd hear was that we lived in a “golden era”—the regime’s official language—for which we’d have to thank the Communist Party and its General Secretary, Comrade Nicolae Ceaușescu. All the country’s institutions held regular meetings where everybody, using a language of thought-terminating clichés which we called “wooden language,” had to massage the ego of the “Dear Leader” who made such an era possible. In this language, Ceaușescu was a “skilled helmsman,” a “beloved parent,” and “the exploitation of man by man” had been forever abolished.

During this "golden era” of Communism, when I was barely twenty-one, I got blacklisted as a “person very dangerous for the security of the state” because I had married a dissident. You see, in Communism, the entire family paid for the deeds of any of its members, including those of the dead ones. My husband’s main guilt was that he was the brother of a famous Romanian journalist who worked abroad for one of the Western radio stations that condemned the injustices of Communism. To understand why this was considered a crime, you need to know that the first thing Ceaușescu did every day was read a report on what had been said about him the previous day.

Since his fate was already sealed and he wasn’t even allowed to go to college, my husband and a few friends tried to create a political party that would have been an alternative to the only official one. Needless to say in a country where one in four citizens was an informant, they were quickly apprehended and subjected to harsh interrogations. This happened before my husband and I met; him being too traumatized to talk about it, I found out from his parents how he had been imprisoned and cruelly beaten. After we got married, he signed a petition demanding that the regime stop the demolition of villages and churches, a project Ceaușescu had started because he realized that the traditional rural lifestyle still gave people some independence. Consequently, Ceaușescu put us under 24-hour surveillance, with a car constantly parked in front of our building. We were young and foolish, and so we made fun of the unending series of spies who were struggling to remain inconspicuous every time we went out and they followed us. Sometimes we mocked them overtly, laughing out loud as we hopped on a bus, while they remained outside, but it was a dangerous game: you never knew when an “accident” could happen.

One afternoon, an individual in a black leather jacket got out of the car parked in front of our building while holding an envelope in his hand, entered for a few seconds, then returned with his hand empty. We didn’t keep the letter that my husband had retrieved from our mailbox because it made him so furious he tore it to pieces. The letter warned that “some people” might want to hurt me badly. The police summoned me a few days later to their headquarters for an undisclosed matter, with my husband forced to wait outside. Nothing horrible happened to me that day, save for the fact that I was asked to wait for several hours while my husband remained outside, not knowing when—or if—I was going to come out. When I was finally brought into an office, the officer informed me in a performatively worried tone that “some people” wanted to hurt me, and he wanted to make me aware of this danger.

This is how we lived for about two years until the anti-Communist Revolution from December 1989 swept the dictator and his clique away.

In the first week after the dictator was killed a member of the newly formed Front of the National Salute—the revolutionary organization that replaced the Communist Party and of which my husband was briefly a member—came to our home to uninstall a microphone that the Securitate (the Secret Police) had hidden behind our bed.

It took another quarter of a century until my husband was allowed to see the file the Secret Police had on us. It contained two thousand pages of content produced through the coordinated efforts of dozens of individuals and tens of thousands of dollars spent every month on our surveillance—in a country in which the average income was forty dollars. It also included the names of the “friends" who had informed on us—some of which we’d already guessed, others, a surprise. Our Secret Police file remained open until December 1991, that is, two years after the regime had fallen, and three months after we had left the country for America.

--

I left the building where my parents lived almost forty years ago, but when I last visited, some of the neighbors I had growing up were still there. Imagine passing by an old man who looks twenty years older than you, and then remembering that you had a crush on him when you were twelve and he was fourteen. The grey Soviet flats have remained unchanged, but in a certain way give you the reassuring feeling that time stands still and there's a continuity between generations—something absent in ever-changing American society.

While the memory of life in the small town of my childhood is ambivalently hazy, when I remember the rural world of my grandparents a wave of nostalgia washes over me. The three-legged wobbling chairs, the haystack above the cow barn where I used to read, even the short-lived doll made of rags that a friend from across the street had taught me how to make, ephemeral as she was, is now bathed in a golden aura of longing for a lost world.

[ Photos of Alta's grandparent's home, taken during a recent visit to Romania. On the left is the cow barn where Alta used to read. ]

I sometimes look at the children of my American friends, with their room full of toys, and I know that their toys don’t make them any happier than my rag doll had made me. And I know that my American female friends, emancipated as they are from the “patriarchy,” aren’t happier than Grandmother. In all traditional societies, labor is organized according to the existence of the two sexes and this has nothing to do with anyone’s “oppression.” Men do some things, women do other things—it's simply a division of labor based on physical differences between the two, and it’s a division that can be observed across cultures and millennia. According to all statistics and their own statements, it’s obvious that many American women are in profound disharmony with themselves and the world in which they live. And this is certainly not because the world in which Grandmother lived was better—although I am wondering more and more whether it was much worse.

The first thing you need to be unhappy is to ask yourself whether you are happy or not—Unlike American women, I am convinced that this is a question Grandmother never asked herself.

Grandmother, just like her mother and her mother’s mother, lived in a way that imitated the lives of previous generations, in an entanglement with “tradition”—the dirty word that American feminists and progressives utter with so much disdain and which they translate as “oppression” and “victimization.” I often try to imagine what Grandmother would have answered had I told her that she was “oppressed” by the patriarchy in particular and society in general. I think she would have had a hard time understanding the concept. You see, it’s hard to feel “oppressed” when you have inner freedom. Aside from this, nobody in the world of my grandparents thought in these terms because in traditional societies it is shameful to be a victim. Only in a world of privilege can victimhood acquire a desirable status. I call this the law of subliminal contradiction, something I discovered by observing how Americans behave. Another example: only in a society of excess can the richest people dress in a way that imitates the homeless. In the society of poverty in which I grew up, it was shameful to wear torn-apart clothes; on the other hand, if you look at the way most well-to-do Americans are dressed today, you’d think they live on the street. Consider high fashion clothing that gives the illusion of poverty and manual labor, like mud-splashes and rips on jeans.

Today I write these lines from France, in my second exile. And many things have changed! My husband is now my ex-husband; he has returned to Romania, and I to Europe. My best friend with whom I used to explore libraries and books, and who grew up in a one-bedroom apartment with two parents, a grandmother, an older sister, and her daughter, and who at ten years old was forced by circumstances to take care of the entire household while her father lay drunk in a ditch and her mother worked on construction sites, is now a doctor and owner of a major medical lab. Unlike my American acquaintances, she never saw herself as a “victim” of anything. When I came to this country as a political refugee over thirty years ago, the thing that most impressed me about Americans was that they were very responsible and resilient. Thirty years later this country has been turned upside-down. But the truth is that the signs and the seeds of this reversal were already present thirty years ago, mostly in one particular space: academia.

The rare Marxists from back then are now the norm (although many traditional Marxists point out that, unlike American academics, Marx was never concerned with “race and gender”). They are the people who call Putin “right-wing,” as if he'd been schooled by the Republican Party rather than the Communist Party, whose Secret Police he represented as an officer of the KGB. The reason Putin is “right-wing” is because he’s a nationalist and anti-LGBT—but if these academics had read any books from my part of the world, they’d know that every single Communist country was ultra-nationalist and homophobic. In Communist Romania you could go to prison for twenty years for being a homosexual. Putin may no longer be a “Communist” because the gifts of the Capital are way too sweet, but his authoritarianism is rooted in Communism nonetheless, and his homophobia has nothing to do with being “right-wing” unless you project a Western value system onto a completely different world in which the categories of Left and Right merge.

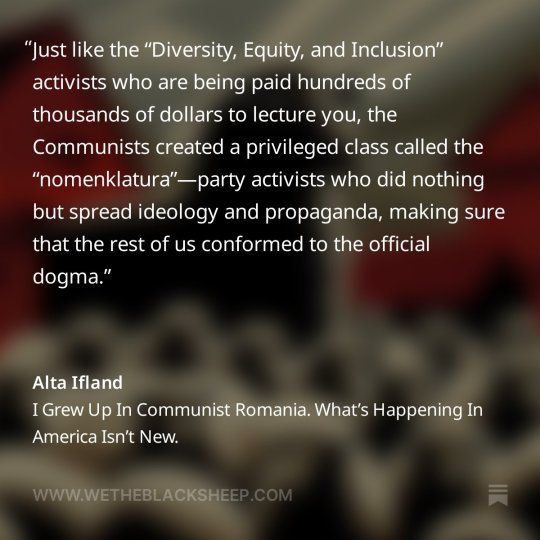

After you’ve experienced the clichés of Communist propaganda, you can easily spot the mental structures underlying the impulse to reduce the complexity of the world down to one huge power struggle in which everybody is either an oppressor or a victim. This is why having lived through Communism has become very useful in contemporary America, and it's why the few of us who denounced the insanity of Communism when it could have cost our lives won’t keep our mouths shut now that America is losing its mind. For instance, the concept of “reparations” based on inherited collective guilt is eerily similar to the Communist practice of punishing an entire family for the deeds of any of its members, including the dead. Just like the “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” activists who are being paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to lecture you, the Communists created a privileged class called the “nomenklatura”—Party activists who did nothing but spread ideology and propaganda, making sure that the rest of us conformed to the official dogma. One trait of people who create dogmatic ideologies is that they never feel obligated to obey their own dogma—if they did, they would have to cancel their own privilege.

Because history is always written from one point of view, being an American academic often comes with the privilege of (re)writing history. And in an Americentric world, these academics look at everything through the lens of their own history, which they project onto everybody else. When have you ever heard academics from English departments and Women/Gender/Ethnic Studies—who have been teaching generations of students about the evils of European colonization—denounce the colonization of Eastern Europe by the Russians and by the Turks? It’s as if 500 years of history—the history of the Ottoman Empire—never existed. Or as if Russia started its colonial history with the invasion of Ukraine.

According to these academics, being European is equivalent to having a mysterious essence called “whiteness,” and I should repent for my “white privilege” and Europe’s colonial history, as if my “white” ancestors had colonized anyone and not the other way around, or as if they had enslaved “brown” Muslims and not the other way around.

Let me tell you an anecdote about how I was made to pay for my “white privilege.” You may remember the brouhaha after the poem performed by the young, black author, Amanda Gorman, at Biden’s inauguration, was commissioned to be translated into Dutch not by another black woman, but by a white person. This white person happened to be Marieke Lukas Rijneveld, who identifies as “non-binary” and is a few years older than Gorman. After a complaint that the chosen translator was not black, the translator withdrew from the project and the publisher issued a public apology—never mind that it was Gorman herself who had chosen the translator and that it’s quite likely that there aren’t many black translators who translate into Dutch and have Rijneveld’s literary skills. I know this because I had read Rijneveld’s award-winning book translated into English and recommended it on social media. When the scandal broke, many American translators—some of whom I was personally acquainted with through my work as a translator—commented on the affair online, supporting the decision to replace the white translator with a black translator. In response, I dared to share the comment of a French member of PEN, who believed that skin color should have nothing to do with who translates what. I accompanied this comment with my own: “I think that, this being a forum of translators, we should give a voice to different opinions from other languages.” I was subjected to a pile-on of virulent attacks, summoned to delete my “inflammatory” remarks, and it was made clear to me that my opinion could only be the result of my “white privilege” because I was (I'm not kidding you) a “cultural essentialist.” The cherry on top was that I was also called a “transphobe” because I had “misgendered” Rijneveld—the irony being that I was the only one in that group who had actually read and supported the “non-binary” author. I left these discussions after it was clear that I didn’t have the “revolutionary consciousness” to belong.

The fact is that nothing—and certainly not “white privilege” or any kind of “systemic” anything—is stopping anyone in America from learning languages and translating. When I was a graduate student in French at the University of Florida, my black classmate had spent time in France, just like everybody else in our program. I was the only one who had never been to France. Yet if I could learn French while believing that I would never see France because traveling to Western Europe was, for a Romanian of my station, as impossible as going to Mars, then any American—black, blue, or purple—can do it.

Privilege is a funny thing, especially in a society in which being a victim grants the highest social status. I for one prefer to assume the privilege of having experienced both Communism and life as an immigrant—a privilege America’s social justice warriors will never have—because it has taught me that you can be free under the worst dictatorship and a slave to groupthink in the freest of worlds.

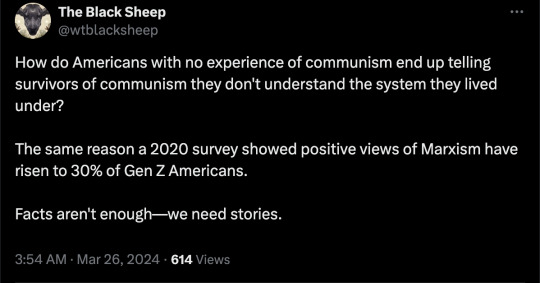

==

#SmashCapitalism

🤡

#Alta Ifland#We The Black Sheep#communism#capitalism#smash capitalism#Marxism#late stage Marxism#Communist Party#religion is a mental illness

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

On a previous ask, someone asked about racial capitalism and like what makes it different from regular capitalism

Yeah, I didn't explain what the term meant, although I wasn't asked that before.

To start with, according to Cedric Robinson in Black Marxism (1983), there is no difference because all forms of capitalism are racial capitalism, that capitalism by its nature produces racial oppression when it produces inequality.

So why coin the term?

The main thing that Robinson was trying to do was to shift the focus of Marxist thought on capitalism towards the way that capitalism extracts value specifically from the racially marginalized.

This has a lot to do with fights within Marxism about how to think about capitalism - for example, Robinson isn't a fan of the idea from Marx that capitalism was a progressive force vis-a-vis feudalism, and argues that capitalism simply displaced caste systems from Europe to Europe's colonies in the Americas, Asia, Africa, etc. through slavery and colonialism and later systems of racial oppression.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

RRR, Black Adam and the Response of the Oppressed

OR: The Colonial Wound and how to approach Violence as a solution against the mechanisms of oppression

OR: how to get the debate right VS how to ruin it completely

Spoiler: RRR gets it right

So, I was keeping this one to myself because it's a very delicate subject, but rejoicing in RRR's recent Golden Globe nomination, I thought hell might as well talk about it.

First of all, a very important disclaimer:

I am not here, in any way, defending or endorsing any side in this debate. My personal views on violence and armed struggle and guerrilla warfare are not what I will be addressing. Armed struggle, is an extremely complex issue that is still being debated today by theorists and academics much more qualified than I am, so no.

Rather, my aim here is simply to address how this debate has been represented, and my take on this issue: media portrayals of social, historical and most importantly, decolonial debates. And recently in 2022, we've had two approaches (And yes, I am fully aware that this topic is much better covered in dozens of media that have this debate entirely as their main focus, but I am talking about superhero blockbusters here, so keep that in mind) that may seem similar, but are fundamentally completely divergent:

The Telugu movie RRR (Rise, Roar, Revolt)

And curiously, DC Film's Black Adam

No need to say, there'll be major spoilers ahead, so be warned

1. THE RESPONSE OF THE OPRESSED

Before I start, I would like to clarify as briefly as I can some terms and concepts that I consider necessary to begin to understand decolonialism and the response of the oppressed, a term that was coined in the famous quote by Jaylen Brown during the height of the BLM movement, "Do not confuse the response of the oppressed with the violence of the oppressor".

Pierre Bourdieu differentiates the violence of the oppressor into two categories:

explicit violence – in which the action of the dominant subject is visible (and therefore, in our current society, subject to questioning and legal or moral limitations)

and symbolic violence – conceptualized by Bourdieu when he addressed the issue of male domination in society and all the faces in which it presents itself – and we see it everywhere, from racial demographics in income distribution to that homophobic joke your uncle always makes.

This relationship of systematic domination can be understood as a chain, and in view of the necessary rise of awareness and consequent rupture of this chain, Audre Lorde presents the uses of anger.

By connecting the idea of symbolic power and the breaking of the domination relationship with the use of anger, we have the explosion of a natural reaction of the oppressed triggered by centuries of imprisonment in their own fear and, bringing this reality specifically to colonial relations, using anger over your own fear results in liberation. (source)

And although it wouldn't hurt to address the revolutionary terms in its most famous roots in the French Revolution and etc, here it seems more fitting to comment on Marx. And class struggle.

Briefly, Marx and Engels saw revolution as the result of organized political action by the exploited. Therefore, one can only speak of revolution when there is a rupture with the old political, social and economic order; and in its place, new standards of social relations are established whose principle is to ensure freedom and social equality among men.

This is what we mean when we talk about inverting the social order, and Marx will also use the terms infrastructure (productive forces + relations of production) and superstructure (politics, police, army, law, morals, religion, etc.).

The superstructure, for Marx, is created by the most favored and dominant class, but determined or conditioned by the infrastructure.

Therefore, the revolution would happen when the working class (and in that logic, any oppressed group) reversed the order and took control of the superstructure.

In short, this can be understood as the basis of revolutionary thinking.

Now apply this to the invasion, colonization and genocide scenario, and you'll see where I'm going here.

KKKKKKKKKKKKKK THAT'S A BIT EXTREME EXAMPLE SORRY but actually in Black Panther I the plot could very well be read through Marxist lens (and that has certainly been done), but I won't even go into that here, god forbid Wakanda Forever hahahah imagine that, anyway going back to my thread

2. ARMED STRUGGLE

A quick definition of armed struggle, which can be found in dictionaries, is armed resistance against oppressive regimes. In the armed struggle, the militants understand that the situation of society requires drastic action so that it can be modified, and for this reason they decide to take up arms and declare war on the oppressive regime. Guerrilla warfare is an example of armed struggle.

In the armed struggle, a group of militants opposed to the current regime in a given society, organize actions that can be strikes, attacks on barracks or public buildings, etc, aiming to destabilize the current power with the aim of overthrowing it and placing a different regime in its place, like a democracy, for example – in general, the armed struggle follows a leftist tendency. (source)

In Brazil, for example, the armed struggle appeared mainly as resistance to the Military Dictatorship between 1964 and 1985.

All of this goes along the idea of using violence as resistance to oppression (as already pointed out before): fire is answered with fire. In the specific scenario of the guerrilla, the French philosopher, journalist, former government official and academic Jules Régis Debray writes the controversial book Révolution Dans La Révolution, where he points out that "The main objective of a revolutionary guerrilla is the destruction of the enemy's military potential"; the enemy is stripped of it's military power (it's weapons) to ensure a greater chance of victory.

"To destroy an army you need another army.", Debray says. "Precisely because it is a mass struggle, and the most radical of all, the guerrillas need, in order to triumph militarily, to gather politically around themselves the active and organized majority, since it is the general strike and the generalized urban insurrection which will give the coup de grace to the regime and destroy its latest maneuvers - last minute coup d'état, provisional junta, elections - by extending the struggle throughout the country." (source)

Does that all ring a bell?

Sure it does.

Now, these are all historical scenarios, and nowadays the moral debates about armed struggle have become extremely more complex (as they should), and the disarmament discourse is taking more and more space in these debates. Is armed struggle the only solution? Wouldn't there be others?

But it is still a complex debate. The Brazilian rapper (and political thinker and, dare I say, philosopher) Mano Brown, a strong advocate of disarmament, staunchly defends that violence, most of the time, bounces back on the oppressed, not the oppressor.

Look at him all precious

He argues, however, that one cannot simply condemn the oppressed who react violently. Already in 2006 he presented in an interview that:

"I am in favor of disarmament, but this argument is difficult, things should be done differently […] People are coming as a class struggle, you know? Rich people don't want poor people to arm themselves and remain unarmed. And poor people don't want rich people to arm themselves and remain unarmed. Did you see the kid's argument: "How are the police allowed to carry guns while I remain unarmed? " It's kind of uneven. It's confusing."

(source - translated by me)

Mano Brown is part of the Brazilian rap band Racionais formed by 4 black men from the periphery, who revamped their music after realizing that it could be used to foment violence. They front a series of social programs, and revolutionized the way peripheral music is seen and consumed. Nowadays, in 2023, Mano Brown hosts one of the biggest political interview podcasts in Brazil (having even interviewed Angela Davis), is considered one of the most active leaders of the racial struggle, and along with the other members of Racionais, has taught open classes in estate universities.

The Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire, considered one of the most notable thinkers in the history of world pedagogy, inaugurates in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (you can read it translated right here) the idea of the liberation pedagogy. He strongly emphasizes that liberation pedagogy is a political process that aims to awaken individuals from their oppression and generate actions for social transformation – through education.

NOW WITH ALL THAT IN MIND WE CAN FINALLY MOVE ON TO WHAT MATTERS,

3. THE MOVIES

I'm going to talk about RRR here first because it makes me happier, but for reasons of time and your patience I'm not going to extend myself so much in the analysis of this film technically, and if you want a more detailed look at the grandeur and the importance and the genius of this film, please watch any of the many videos that are now appearing on youtube on the subject (I recommend RRR: Make Movies EPIC Again, by Jared Bauer, and The Importance of RRR, by the wonderful Accented Cinema)

ONCE AGAIN ATTENTION FOR BIG, MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD

The story therefore revolves around two men: Raju, who infiltrates the British army to steal fireguns and deliver them to the people's guerrilla, and Bheem, a Gond leader who is after Mali, a child of his people who was kidnapped by the British to basically serve as a pet.

They meet under false identities, and unaware that they were both fighting for the liberation of India (through different methods), the two men form an extremely strong bond of love and friendship, which results in their struggles coalescing into an evocation of patriotic unity and popular resurgence against the colonial forces.

First of all, RRR is a fictionalized biography of two real-life Indian revolutionaries, Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem. So, in real life, Alluri Raju actually stole guns from the British to stage uprisings against the British Raj, and Komaram Bheem really was a Gond revolutionary leader who coined the slogan Jal, Jangal, Zameen (transl. Water, Forest, Land) wich became a call to action for Adivasis (or Scheduled Tribes) peoples.

You can see the flag in the last scenes

This "historical aspect" (in addition to the incredible, completely impossible and impossibly glorious action scenes) makes it plausible to draw parallels between RRR and Tarantino's historical revisionism films like Django Unchained (2013) and Inglourious Basterds (2009), where in all cases we see scenes of extreme violence that somehow feel justified, or cathartic, for being directed against oppressors (slave masters, Nazis, British colonizers, etc etc)

The parallels are just there.

Black Adam, on the other hand, states in its synopsis that "After nearly five thousand years of imprisonment, Black Adam, an anti-hero from the ancient city of Kahndaq, is released in modern times. His brutal tactics and righteous ways attract the attention of the Justice Society of America, who try to stop his rampage by teaching him to be more of a hero than a villain, and they all must band together to stop a force more powerful than Adam himself."

So we have a superhero story set in the present day in a fictional country on the Sinai Peninsula (that means, right there besides the Gaza Strip and the Suez Canal), occupied by a mercenary crime syndicate called Intergang, who brutally oppresses the Kahndaqi people while robbing their mineral resources. All good, all great.

But as stated in the synopsis, the film's great moral conflict revolves around whether the use of violence against mechanisms of oppression is justified or not.

Basically,

And while these two scenarios may seem similar, the approach the two films take to this debate, which, as I've said before, is EXTREMELY DELICATED, and EXTREMELY COMPLEX, is completely different. Firstly, because RRR is the only one of the two that treats it as, well, a debate.

From the beginning, RRR establishes the two characters as essentially polar opposites; Raju is fire

Look at the scenery with the european buildings in the background

Bheem is water

And here, the native, untouched forest with pure cristaline water

Bheem is the god Bhima, immovable, patient and resilient

(like water)

And Raju is the god Rama, heroic, springy and skillful

(and hot)

Bheem is the legs (the foundation) while Raju is the arms (the action)

They ✨ complement ✨ each other

And this is translated into their different approaches to the revolution: Raju with his arms policy (inherited from his guerrilla father), who operates within the system to overthrow it, and Bheem with his native philosophy, using the land, the fauna, the culture, the religion, the people themselves as agents against oppression, operating from outside the system to overthrow it.

At the beginning of the film, Raju dresses Bheem in western clothing so that he can attend a British party (which allows him to know the building and locate Mali), and at the end of the film, Bheem dresses Raju in the traditional clothing of the god Rama, and arms him not with european firearms but with a sacred bow and arrow, evoking his native homeland in what configures the real defeat of the colonizers.

Not even getting into the merits of comparing these two films technically, just talking about the discourse itself, what for me fundamentally separates RRR from Black Adam, and even Django and Inglourious Basterds, is precisely Bheem's character. It's the other way to fight (but fight nonetheless)

This does not mean that the armed struggle is delegitimized, or diminished. On the contrary, it is explained, justified (within that historical and social context) and respected. People who fought in the armed struggle, and died in the armed struggle, are honored and respected. It allows you to understand where the idea of arming the population is coming from (in a certain parallel with Mano Brown's interview that I mentioned above), but it also presents other discussions on the subject, that happened at the time, and still happens today.

And above all, as I mentioned before, the film presents and reinforces the idea of inspiration. Even if education is presented only very briefly, in a popular assembly, in the long term, the film still gives extreme focus to the importance of raising awareness among the oppressed people.

This can be clearly seen in the scene where Bheem is being tortured in a public square by the British government, and refuses to kneel.

So when the torture becomes too much to bear, he starts to sing

Now, this is the most important scene in this movie and I'll die on this hill

And then, this happens

Bheem inspires not only the population, but also Raju, who even after years of enticement by his own father, steps back on his original (armamentist) plan when he realizes that "I was under the impression that guns would bring us freedom. But Bheem inspired a whole crowd with one song"

Even though in the context of the film the "path of choice" was still violent (this still is, after all, an action superhero movie), the message of this scene is extremely metaphorical. The idea of a song (art) inspiring all people to "become a weapon" against an oppressive regime is very powerful, and it resonates deeply in anti-opression movements all over History. It is, literally, the power of the people.

Furthermore, at crucial moments in the plot, both Bheem and Raju put aside their collective struggles for the other's individual good; Unlike his father, who readily accepts the militarization of his child son for the greater good, Raju, when questioned by his guerrilla companion for abandoning 15 years of work to save Bheem, says that "I will bear it for another 25 years, but I won't sacrifice Bheem for my goal".

Bheem, here, represents not only the friendship and love between them, but, metaphorically, an entire ideal of the people. Ultimately, one can say that this film addresses the idea of "what are the limits in my revolution": I will not sacrifice the other for my revolution; the limits of my revolution must be the wellness of the other (and in our metaphorical reading here, the wellness of the people).

Parallel, the torture scene can be metaphorically read as: the only valid sacrifice is my own, never that of the other. (and I won't be commenting on the revolutionary character of ideas like martyrdom and self-sacrifice, but yes). That's what Bheem and Raju do throughout the entire film, they put the other above themselves.

And in the end, they kill the british defeat oppression together✨

Now, as I've mentioned before, yes, this movie still ends violently, yes, it still glorifies and celebrates this violence in some of the best action scenes I've seen in my whole life, yes, it is heavily patriotic and sometimes a little bit too on the nose about it, yes, and did I rejoyce in it? Yes.

But it cannot be denied that RRR at least presents a reflection not often seen in films of the genre, which is the mere existence of real debate. In addition, the film is placed in an extremely specific historical context, portraying real historical figures, real life revolutionaries, folkloric parallels, a gigantic symbolic charge, in short, a whole other deal.

Besides it, the only difference between this film and idk, Braveheart, or Star Wars, is that in this film the social and racial parallels, the guerrilla warfare and class struggle (and the colonial wound) become clearer – and perhaps this is a more responsible way of representing a revolution.

NOW, BLACK ADAM ON THE OTHER HAND KKKKKKK

As mentioned in the synopsis, the background of Black Adam is curiously similar: we have an oppressed people, we have the militia, a clear racial reference to a real-life conflict, which affects thousands of people daily, and the figure of a mythologically evocative hero with super powers who will free the people from oppression through violent means. And yes, there is debate: we have the Justice Society, which condemns Black Adam's methods and questions his use of violence, only to be proven wrong at the end of the movie.

But the "proved wrong" isn't really built, or developed (as Intergang is quickly forgotten when they all start fighting each other and then… Satan? For some reason??), and it basically boils down to this:

KKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKK

And that's so funny because he actually just… killed like 3 soldiers in the second act of the movie. That's all he did.

And it gets even funnier because at some point we have a scene that genuinely makes a VERY VALID point that made me very hopeful when I was in the theater watching it

Like, this is SO VALID and she is SO RIGHT and this is such a great argument and a great debate point and then it just... goes nowhere

He just killed like 3 guys he didn't even talk to the people he just, quite literally, killed some pawn soldiers and went on to fight his own individual battles that had nothing to do with the actual opression state of the country besides them telling you that "it was bad".

The problem with Black Adam's is ac how shallow the argument is. Nothing is justified, nothing is not even debated, we just have Hawk Man going "killing is bad" and Black Adam going "yeah but I do it caused I'm disruptive like that", and even when we have this "inspire the people" moment is just... this kid with a cape doing this symbol and yes, symbols of struggle are a great tool in fighting oppression, and yes they work and they're so, so great, but this one specifically kind of just…was there?

LIKE OK THIS IS ALL GREAT but then it lead to people… fighting zombies?????

zombies ??!?!??!!!????

Like, how, seriously, how does this have to do with any of your previous state of opression? How does this change absolutely anything??? Are we going to have elections after the zombies thing, or... ?

And that, to me, is such a poor and wasteful way of representing people power that, even though I didn't take this film seriously, I couldn't help but feel mildly frustrated. Much of the recent wave of blockbuster media about decolonialism, in my opinion, has been making this same mistake, which is apparently thinking that just because a movie is made to be a blockbuster, or a superhero movie, or an action movie and easy entertainment, it cannot tackle complex topics. It cannot deepen a discussion. It can't take 10 minutes off a fight scene to establish a full dialogue. As if that would, idk, tire the audience maybe? Idk.

As if a universe of superheroes, or fantasy and action, couldn't contain a scene like this:

This scene seems so simple but it is so, so huge

Andor is perhaps an example out of the curve, because Andor is a series that makes a great effort to represent the fight against oppression in a very serious and responsible way, making it its main theme, of representing what a fascist government is,how a fascist government acts and affects all layers of a population, what is the immigrant cause, what is the armed struggle, what is it like to be a person of color in an far-right government. And it does all of this in an unprecedented way in the genre so far, indeed.

But as I said before, perhaps this should be how all media represent these themes. Because otherwise, even the best of intentions can turn against the causes you sought to defend. And ok, I know that Black Adam is "just a superhero movie" and that maybe it's unfair to demand so much from a movie that only came to propose a simple entertainment with fight scenes and jokes, and I had fun watching it indeed. I love Dwayne Jhonson we all do. But the thing is, if you're going to represent that debate, I genuinely believe it can't be done as simply, or as poorly explained, as it was in this film. A poorly presented arms discourse can become an attack on the legitimization of the armed struggle in its historical context, it can become a justification for a shootout against anti-oppression demonstrations, it can become the excuse for why a policeman mistook an umbrella for a rifle, or a piece of wood for a gun, and killed innocent (and peripheral) men.

In the best of scenarios, the intent is simply forgotten, or it's so hidden in the metaphorical layers of the work that it's easy to miss them. If that weren't the case, there wouldn't be so many racist, misogynistic, right-wing Star Wars fans, for example (just to be clear, I'm not attacking Star Wars here at all, ok, I'm just using it as an example – you'll agree with me that I've never seen any Cambridge professors attack Star Wars)

And fair is fair, Luke did explode a moon-sized military base full of millions of people and all that...

SO ANYWAY

Armamentism is an extremely serious issue, and it must be handled very, very carefully. As I mentioned before, RRR has a historical context, and an argument builded throughout the entire film; I hardly think anyone comes out of RRR, or WomanKing, wanting to pick up a gun and simply shoot someone (I hope). But the way this idea was presented in Black Adam, it is not an exaggeration to say that someone might have had this impression after watching it. At the very least, the movie took no care making sure this wasn't the case, and that for me is troubling enough.

The struggle against oppression and decolonialism are extremely important topics, and I am happy that these themes are increasingly making themselves present in more and more media works (and we have had several very good ones recently) – and Black Adam does have good ideas in the middle of the mess. But if you're going to make a film to talk about oppression, without actually commiting to approach it responsibly, why do it?

And ok, RRR does have a very imperative call to action but well, look at them, would you not answer???

#decolonialism#rrr movie#rrr#black adam#dc#dc universe#indian cinema#guerrilla I guess#star wars#andor series#andor#marx#marxism#killmonger#black panther#dwayne johnson#response of the opressed#racisim#movie essay#movie gifs#revolution#antifascism

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Biko Agozino

While I support the call for more originality by scholars of African descent, I demonstrated that some of the most original thinkers in the Africana tradition are decidedly Marxist without apology precisely because Marxism allows room for internal criticism in the concrete analysis of concrete situations, Marx borrowed from Africana traditions of intellectual and moral leadership, and the Marxist perspective has a track record of sticking up for struggles against racism-sexism-imperialism.

#Marxism#Africa#Black liberation#Karl Marx#capitalism#imperialism#national liberation#socialism#communist#Biko Agozino#Struggle La Lucha

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

#malcolm x#malcom x#political quotes#political posting#political#politics#social justice#current events#spreading awareness#black history#black history month#human rights#leftist politics#leftist#leftism#socialist politics#socialist#socialism#marxist#marxism#communist#communism#quotes to live by#quote#quotation#quotes#inspiring quotes#relatable quotes#life quote#late stage capitalism

16 notes

·

View notes