#environmental philosophy

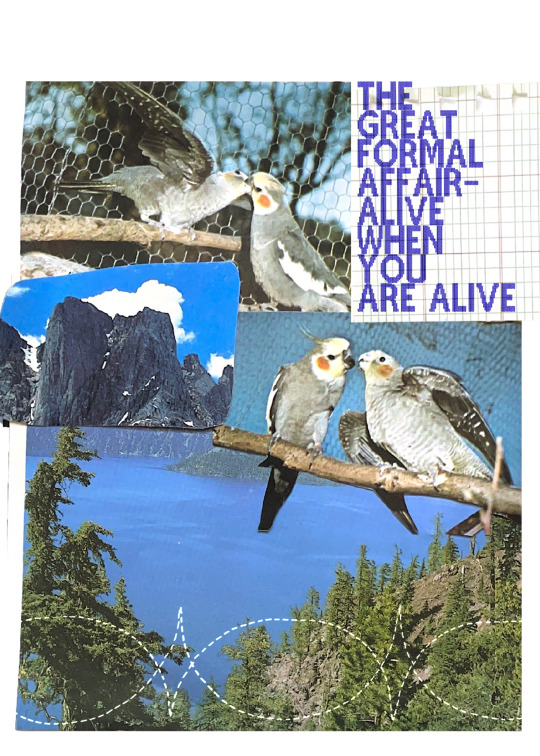

Text

life has an inner side

#companion piece for an article about enlivenment#andreas weber#environmental philosophy#poetic precision#etc#collage#journal#art journal#collage art#my writing#my art#poetry#scrapbook

819 notes

·

View notes

Text

Existence Value: Why All of Nature is Important Whether We Can Use it or Not

I spend a lot of time around other nature nerds. We’re a bunch of people from varying backgrounds, places, and generations who all find a deep well of inspiration within the natural world. We’re the sort of people who will happily spend all day outside enjoying seeing wildlife and their habitats without any sort of secondary goal like fishing, foraging, etc. (though some of us engage in those activities, too.) We don’t just fall in love with the places we’ve been, either, but wild locales that we’ve only ever seen in pictures, or heard of from others. We are curators of existence value.

Existence value is exactly what it sounds like–something is considered important and worthwhile simply because it is. It’s at odds with how a lot of folks here in the United States view our “natural resources.” It’s also telling that that is the term most often used to refer collectively to anything that is not a human being, something we have created, or a species we have domesticated, and I have run into many people in my lifetime for whom the only value nature has is what money can be extracted from it. Timber, minerals, water, meat (wild and domestic), mushrooms, and more–for some, these are the sole reasons nature exists, especially if they can be sold for profit. When questioning how deeply imbalanced and harmful our extractive processes have become, I’ve often been told “Well, that’s just the way it is,” as if we shall be forever frozen in the mid-20th century with no opportunity to reimagine industry, technology, or uses thereof.

Moreover, we often assign positive or negative value to a being or place based on whether it directly benefits us or not. Look at how many people want to see deer and elk numbers skyrocket so that they have more to hunt, while advocating for going back to the days when people shot every gray wolf they came across. Barry Holstun Lopez’ classic Of Wolves and Men is just one of several in-depth looks at how deeply ingrained that hatred of the “big bad wolf” is in western mindsets, simply because wolves inconveniently prey on livestock and compete with us for dwindling areas of wild land and the wild game that sustained both species’ ancestors for many millennia. “Good” species are those that give us things; “bad” species are those that refuse to be so complacent.

Even the modern conservation movement often has to appeal to people’s selfishness in order to get us to care about nature. Look at how often we have to argue that a species of rare plant is worth saving because it might have a compound in it we could use for medicine. Think about how we’ve had to explain that we need biodiverse ecosystems, healthy soil, and clean water and air because of the ecosystem services they provide us. We measure the value of trees in dollars based on how they can mitigate air pollution and anthropogenic climate change. It’s frankly depressing how many people won’t understand a problem until we put things in terms of their own self-interest and make it personal. (I see that less as an individual failing, and more our society’s failure to teach empathy and emotional skills in general, but that’s a post for another time.)

Existence value flies in the face of all of those presumptions. It says that a wild animal, or a fungus, or a landscape, is worth preserving simply because it is there, and that is good enough. It argues that the white-tailed deer and the gray wolf are equally valuable regardless of what we think of them or get from them, in part because both are keystone species that have massive positive impacts on the ecosystems they are a part of, and their loss is ecologically devastating.

But even those species whose ecological impact isn’t quite so wide-ranging are still considered to have existence value. And we don’t have to have personally interacted with a place or its natural inhabitants in order to understand their existence value, either. I may never get to visit the Maasai Mara in Kenya, but I wish to see it as protected and cared for as places I visit regularly, like Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. And there are countless other places, whose names I may never know and which may be no larger than a fraction of an acre, that are important in their own right.

I would like more people (in western societies in particular) to be considering this concept of existence value. What happens when we detangle non-human nature from the automatic value judgements we place on it according to our own biases? When we question why we hold certain values, where those values came from, and the motivations of those who handed them to us in the first place, it makes it easier to see the complicated messes beneath the simple, shiny veneer of “Well, that’s just the way it is.”

And then we get to that most dangerous of realizations: it doesn’t have to be this way. It can be different, and better, taking the best of what we’ve accomplished over the years and creating better solutions for the worst of what we’ve done. In the words of Rebecca Buck–aka Tank Girl–“We can be wonderful. We can be magnificent. We can turn this shit around.”

Let’s be clear: rethinking is just the first step. We can’t just uproot ourselves from our current, deeply entrenched technological, social, and environmental situation and instantly create a new way of doing things. Societal change takes time; it takes generations. This is how we got into that situation, and it’s how we’re going to climb out of it and hopefully into something better. Sometimes the best we can do is celebrate small, incremental victories–but that’s better than nothing at all.

Nor can we just ignore the immensely disproportionate impact that has been made on indigenous and other disadvantaged communities by our society (even in some cases where we’ve actually been trying to fix the problems we’ve created.) It does no good to accept nature’s inherent value on its own terms if we do not also extend that acceptance throughout our own society, and to our entire species as a whole.

But I think ruminating on this concept of existence value is a good first step toward breaking ourselves out first and foremost. And then we go from there.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#nature#natural history#ecology#wildlife#animals#environment#environmentalism#conservation#existence value#deep ecology#science#scicomm#environmental philosophy#climate change

556 notes

·

View notes

Text

[The] dual paradigm linking action on nature and civilization possesses its manifesto: Buffon’s Époques de la nature, one of the high points of the climatic hubris of the modern age [...] Armed with evidence of the warming of America and Europe, Buffon became the champion of a veritable climate utopia: were they to give up tearing one another apart, civilized nations could rationally transform the planet. For in planting and felling trees judiciously, man could ‘alter the influences of the climate he inhabits and fix, as it were, its temperature at the point that suits him’. And because, for Buffon, terrestrial temperatures were what determined the emergence over time of new living species, this geo-engineering would lead to the birth of a new vegetable and animal world fashioned by man.

— Jean-Baptiste Fressoz & Fabien Locher (translated by Gregory Elliott), Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#environmentalism#book quotes#book quote#quote#quotes#philosophy#environmental philosophy#environmental science#environmental justice#environment#climate change#climate crisis#climate anxiety#climate emergency#gradblr#studyblr#academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#philosophy quotes#global warming#climate strike#colonialism#imperialism#nature#bioengineering#transhumanism#solarpunk#ecopunk#dystopia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

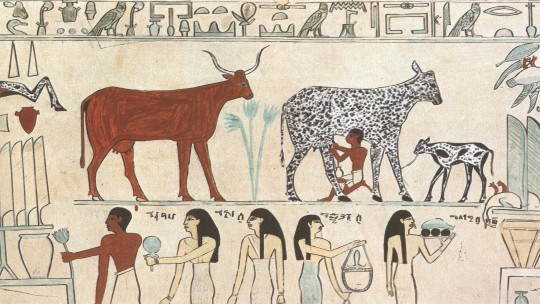

With the ‘discovery’ of America, the idea took root that colonization was also a climatic normalization, a way of improving the continent’s climate by clearing and cultivating land. It was a promise to the colonists and a discourse of domination: a way of saying that native peoples had never really owned the New World. In the eighteenth century, acting on the climate served to rank societies and their historical trajectories hierarchically: Amerindian peoples still in the infancy of a savage climate; European peoples creating the mild climate of their continent; Oriental peoples destroying theirs. The Maghreb, India and, later, Black Africa: in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the French and British empires were built on accusing Blacks and Arabs, Islam, nomadism, and the ‘primitive’ mentality, of wrecking the climate. Colonization was conceived and presented as an attempt to restore Nature. The white man must mend the rains, make the seasons milder, push back the desert – and to that end command the natives.

— Jean-Baptiste Fressoz & Fabien Locher (translated by Gregory Elliott), Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#climate change#colonialism#colonization#imperialism#occupation#ecology#conservation#nature#book quotes#climate crisis#climate emergency#extinction rebellion#environmental justice#environmental science#environmental activism#environmental philosophy#philosophy#philosophy quotes#biology#biomes#settler colonialism#social science#science#gradblr#studyblr#academia#writeblr#writeblr community#racism#cw racism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

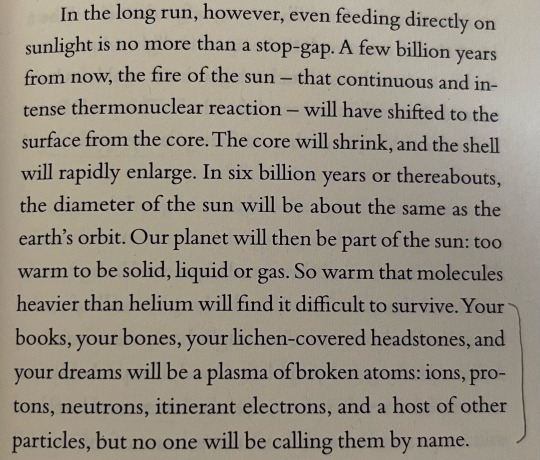

excerpt from learning to die by robert bringhurst & jan zwicky

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chapter VI. Fourth Period. — Monopoly

1. — Necessity of monopoly.

Thus monopoly is the inevitable end of competition, which engenders it by a continual denial of itself: this generation of monopoly is already its justification. For, since competition is inherent in society as motion is in living beings, monopoly which comes in its train, which is its object and its end, and without which competition would not have been accepted, — monopoly is and will remain legitimate as long as competition, as long as mechanical processes and industrial combinations, as long, in fact, as the division of labor and the constitution of values shall be necessities and laws.

Therefore by the single fact of its logical generation monopoly is justified. Nevertheless this justification would seem of little force and would end only in a more energetic rejection of competition than ever, if monopoly could not in turn posit itself by itself and as a principle.

In the preceding chapters we have seen that division of labor is the specification of the workman considered especially as intelligence; that the creation of machinery and the organization of the workshop express his liberty; and that, by competition, man, or intelligent liberty, enters into action. Now, monopoly is the expression of victorious liberty, the prize of the struggle, the glorification of genius; it is the strongest stimulant of all the steps in progress taken since the beginning of the world: so true is this that, as we said just now, society, which cannot exist with it, would not have been formed without it.

Where, then, does monopoly get this singular virtue, which the etymology of the word and the vulgar aspect of the thing would never lead us to suspect?

Monopoly is at bottom simply the autocracy of man over himself: it is the dictatorial right accorded by nature to every producer of using his faculties as he pleases, of giving free play to his thought in whatever direction it prefers, of speculating, in such specialty as he may please to choose, with all the power of his resources, of disposing sovereignly of the instruments which he has created and of the capital accumulated by his economy for any enterprise the risks of which he may see fit to accept on the express condition of enjoying alone the fruits of his discovery and the profits of his venture.

This right belongs so thoroughly to the essence of liberty that to deny it is to mutilate man in his body, in his soul, and in the exercise of his faculties, and society, which progresses only by the free initiative of individuals, soon lacking explorers, finds itself arrested in its onward march.

It is time to give body to all these ideas by the testimony of facts.

I know a commune where from time immemorial there had been no roads either for the clearing of lands or for communication with the outside world. During three-fourths of the year all importation or exportation of goods was prevented; a barrier of mud and marsh served as a protection at once against any invasion from without and any excursion of the inhabitants of the holy and sacred community. Six horses, in the finest weather, scarcely sufficed to move a load that any jade could easily have taken over a good road. The mayor resolved, in spite of the council, to build a road through the town. For a long time he was derided, cursed, execrated. They had got along well enough without a road up to the time of his administration: why need he spend the money of the commune and waste the time of farmers in road-duty, cartage, and compulsory service? It was to satisfy his pride that Monsieur the Mayor desired, at the expense of the poor farmers, to open such a fine avenue for his city friends who would come to visit him! In spite of everything the road was made and the peasants applauded! What a difference! they said: it used to take eight horses to carry thirty sacks to market, and we were gone three days; now we start in the morning with two horses, and are back at night. But in all these remarks nothing further was heard of the mayor. The event having justified him, they spoke of him no more: most of them, in fact, as I found out, felt a spite against him.

This mayor acted after the manner of Aristides. Suppose that, wearied by the absurd clamor, he had from the beginning proposed to his constituents to build the road at his expense, provided they would pay him toll for fifty years, each, however, remaining free to travel through the fields, as in the past: in what respect would this transaction have been fraudulent?

That is the history of society and monopolists.

Everybody is not in a position to make a present to his fellow-citizens of a road or a machine: generally the inventor, after exhausting his health and substance, expects reward. Deny then, while still scoffing at them, to Arkwright, Watt, and Jacquard the privilege of their discoveries; they will shut themselves up in order to work, and possibly will carry their secret to the grave. Deny to the settler possession of the soil which he clears, and no one will clear it.

But, they say, is that true right, social right, fraternal right? That which is excusable on emerging from primitive communism, an effect of necessity, is only a temporary expedient which must disappear in face of a fuller understanding of the rights and duties of man and society.

I recoil from no hypothesis: let us see, let us investigate. It is already a great point that the opponents confess that, during the first period of civilization, things could not have gone otherwise. It remains to ascertain whether the institutions of this period are really, as has been said, only temporary, or whether they are the result of laws immanent in society and eternal. Now, the thesis which I maintain at this moment is the more difficult because in direct opposition to the general tendency, and because I must directly overturn it myself by its contradiction.

I pray, then, that I may be told how it is possible to make appeal to the principles of sociability, fraternity, and solidarity, when society itself rejects every solidary and fraternal transaction? At the beginning of each industry, at the first gleam of a discovery, the man who invents is isolated; society abandons him and remains in the background. To put it better, this man, relatively to the idea which he has conceived and the realization of which he pursues, becomes in himself alone entire society. He has no longer any associates, no longer any collaborators, no longer any sureties; everybody shuns him: on him alone falls the responsibility; to him alone, then, the advantages of the speculation.

But, it is insisted, this is blindness on the part of society, an abandonment of its most sacred rights and interests, of the welfare of future generations; and the speculator, better informed or more fortunate, cannot fairly profit by the monopoly which universal ignorance gives into his hands.

I maintain that this conduct on the part of society is, as far as the present is concerned, an act of high prudence; and, as for the future, I shall prove that it does not lose thereby. I have already shown in the second chapter, by the solution of the antinomy of value, that the advantage of every useful discovery is incomparably less to the inventor, whatever he may do, than to society; I have carried the demonstration of this point even to mathematical accuracy. Later I shall show further that, in addition to the profit assured it by every discovery, society exercises over the privileges which it concedes, whether temporarily or perpetually, claims of several kinds, which largely palliate the excess of certain private fortunes, and the effect of which is a prompt restoration of equilibrium. But let us not anticipate.

I observe, then, that social life manifests itself in a double fashion, — preservation and development.

Development is effected by the free play of individual energies; the mass is by its nature barren, passive, and hostile to everything new. It is, if I may venture to use the comparison, the womb, sterile by itself, but to which come to deposit themselves the germs created by private activity, which, in hermaphroditic society, really performs the function of the male organ.

But society preserves itself only so far as it avoids solidarity with private speculations and leaves every innovation absolutely to the risk and peril of individuals. It would take but a few pages to contain the list of useful inventions. The enterprises that have been carried to a successful issue may be numbered; no figure would express the multitude of false ideas and imprudent ventures which every day are hatched in human brains. There is not an inventor, not a workman, who, for one sane and correct conception, has not given birth to thousands of chimeras; not an intelligence which, for one spark of reason, does not emit whirlwinds of smoke. If it were possible to divide all the products of the human reason into two parts, putting on one side those that are useful, and on the other those on which strength, thought, capital, and time have been spent in error, we should be startled by the discovery that the excess of the latter over the former is perhaps a billion per cent. What would become of society, if it had to discharge these liabilities and settle all these bankruptcies? What, in turn, would become of the responsibility and dignity of the laborer, if, secured by the social guarantee, he could, without personal risk, abandon himself to all the caprices of a delirious imagination and trifle at every moment with the existence of humanity?

Wherefore I conclude that what has been practised from the beginning will be practised to the end, and that, on this point, as on every other, if our aim is reconciliation, it is absurd to think that anything that exists can be abolished. For, the world of ideas being infinite, like nature, and men, today as ever, being subject to speculation, — that is, to error, — individuals have a constant stimulus to speculate and society a constant reason to be suspicious and cautious, wherefore monopoly never lacks material.

To avoid this dilemma what is proposed? Compensation? In the first place, compensation is impossible: all values being monopolized, where would society get the means to indemnify the monopolists? What would be its mortgage? On the other hand, compensation would be utterly useless: after all the monopolies had been compensated, it would remain to organize industry. Where is the system? Upon what is opinion settled? What problems have been solved? If the organization is to be of the hierarchical type, we reenter the system of monopoly; if of the democratic, we return to the point of departure, for the compensated industries will fall into the public domain, — that is, into competition, — and gradually will become monopolies again; if, finally, of the communistic, we shall simply have passed from one impossibility to another, for, as we shall demonstrate at the proper time, communism, like competition and monopoly, is antinomical, impossible.

In order not to involve the social wealth in an unlimited and consequently disastrous solidarity, will they content themselves with imposing rules upon the spirit of invention and enterprise? Will they establish a censorship to distinguish between men of genius and fools? That is to suppose that society knows in advance precisely that which is to be discovered. To submit the projects of schemers to an advance examination is an a priori prohibition of all movement. For, once more, relatively to the end which he has in view, there is a moment when each manufacturer represents in his own person society itself, sees better and farther than all other men combined, and frequently without being able to explain himself or make himself understood. When Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, Newton’s predecessors, came to the point of saying to Christian society, then represented by the Church: “The Bible is mistaken; the earth revolves, and the sun is stationary,” they were right against society, which, on the strength of its senses and traditions, contradicted them. Could society then have accepted solidarity with the Copernican system? So little could it do it that this system openly denied its faith, and that, pending the accord of reason and revelation, Galileo, one of the responsible inventors, underwent torture in proof of the new idea. We are more tolerant, I presume; but this very toleration proves that, while according greater liberty to genius, we do not mean to be less discreet than our ancestors. Patents rain, but without governmental guarantee. Property titles are placed in the keeping of citizens, but neither the property list nor the charter guarantee their value: it is for labor to make them valuable. And as for the scientific and other missions which the government sometimes takes a notion to entrust to penniless explorers, they are so much extra robbery and corruption.

In fact, society can guarantee to no one the capital necessary for the testing of an idea by experiment; in right, it cannot claim the results of an enterprise to which it has not subscribed: therefore monopoly is indestructible. For the rest, solidarity would be of no service: for, as each can claim for his whims the solidarity of all and would have the same right to obtain the government’s signature in blank, we should soon arrive at the universal reign of caprice, — that is, purely and simply at the statu quo.

Some socialists, very unhappily inspired — I say it with all the force of my conscience — by evangelical abstractions, believe that they have solved the difficulty by these fine maxims: “Inequality of capacities proves the inequality of duties”; “You have received more from nature, give more to your brothers,” and other high-sounding and touching phrases, which never fail of their effect on empty heads, but which nevertheless are as simple as anything that it is possible to imagine. The practical formula deduced from these marvellous adages is that each laborer owes all his time to society, and that society should give back to him in exchange all that is necessary to the satisfaction of his wants in proportion to the resources at its disposal.

May my communistic friends forgive me! I should be less severe upon their ideas if I were not irreversibly convinced, in my reason and in my heart, that communism, republicanism, and all the social, political, and religious utopias which disdain facts and criticism, are the greatest obstacle which progress has now to conquer. Why will they never understand that fraternity can be established only by justice; that justice alone, the condition, means, and law of liberty and fraternity, must be the object of our study; and that its determination and formula must be pursued without relaxation, even to the minutest details? Why do writers familiar with economic language forget that superiority of talents is synonymous with superiority of wants, and that, instead of expecting more from vigorous than from ordinary personalities, society should constantly look out that they do not receive more than they render, when it is already so hard for the mass of mankind to render all that it receives? Turn which way you will, you must always come back to the cash book, to the account of receipts and expenditures, the sole guarantee against large consumers as well as against small producers. The workman continually lives in advance of his production; his tendency is always to get credit contract debts and go into bankruptcy; it is perpetually necessary to remind him of Say’s aphorism: Products are bought only with products.

To suppose that the laborer of great capacity will content himself, in favor of the weak, with half his wages, furnish his services gratuitously, and produce, as the people say, for the king of Prussia — that is, for that abstraction called society, the sovereign, or my brothers, — is to base society on a sentiment, I do not say beyond the reach of man, but one which, erected systematically into a principle, is only a false virtue, a dangerous hypocrisy. Charity is recommended to us as a reparation of the infirmities which afflict our fellows by accident, and, viewing it in this light, I can see that charity may be organized; I can see that, growing out of solidarity itself, it may become simply justice. But charity taken as an instrument of equality and the law of equilibrium would be the dissolution of society. Equality among men is produced by the rigorous and inflexible law of labor, the proportionality of values, the sincerity of exchanges, and the equivalence of functions, — in short, by the mathematical solution of all antagonisms.

That is why charity, the prime virtue of the Christian, the legitimate hope of the socialist, the object of all the efforts of the economist, is a social vice the moment it is made a principle of constitution and a law; that is why certain economists have been able to say that legal charity had caused more evil in society than proprietary usurpation. Man, like the society of which he is a part, has a perpetual account current with himself; all that he consumes he must produce. Such is the general rule, which no one can escape without being, ipso facto struck with dishonor or suspected of fraud. Singular idea, truly, — that of decreeing, under pretext of fraternity, the relative inferiority of the majority of men! After this beautiful declaration nothing will be left but to draw its consequences; and soon, thanks to fraternity, aristocracy will be restored.

Double the normal wages of the workman, and you invite him to idleness, humiliate his dignity, and demoralize his conscience; take away from him the legitimate price of his efforts, and you either excite his anger or exalt his pride. In either case you damage his fraternal feelings. On the contrary, make enjoyment conditional upon labor, the only way provided by nature to associate men and make them good and happy, and you go back under the law of economic distribution, products are bought with products. Communism, as I have often complained, is the very denial of society in its foundation, which is the progressive equivalence of functions and capacities. The communists, toward whom all socialism tends, do not believe in equality by nature and education; they supply it by sovereign decrees which they cannot carry out, whatever they may do. Instead of seeking justice in the harmony of facts, they take it from their feelings, calling justice everything that seems to them to be love of one’s neighbor, and incessantly confounding matters of reason with those of sentiment.

Why then continually interject fraternity, charity, sacrifice, and God into the discussion of economic questions? May it not be that the utopists find it easier to expatiate upon these grand words than to seriously study social manifestations?

Fraternity! Brothers as much as you please, provided I am the big brother and you the little; provided society, our common mother, honors my primogeniture and my services by doubling my portion. You will provide for my wants, you say, in proportion to your resources. I intend, on the contrary, that such provision shall be in proportion to my labor; if not, I cease to labor.

Charity! I deny charity; it is mysticism. In vain do you talk to me of fraternity and love: I remain convinced that you love me but little, and I feel very sure that I do not love you. Your friendship is but a feint, and, if you love me, it is from self-interest. I ask all that my products cost me, and only what they cost me: why do you refuse me?

Sacrifice! I deny sacrifice; it is mysticism. Talk to me of debt and credit, the only criterion in my eyes of the just and the unjust, of good and evil in society. To each according to his works, first; and if, on occasion, I am impelled to aid you, I will do it with a good grace; but I will not be constrained. To constrain me to sacrifice is to assassinate me.

God! I know no God; mysticism again. Begin by striking this word from your remarks, if you wish me to listen to you; for three thousand years of experience have taught me that whoever talks to me of God has designs on my liberty or on my purse. How much do you owe me? How much do I owe you? That is my religion and my God.

Monopoly owes its existence both to nature and to man: it has its source at once in the profoundest depths of our conscience and in the external fact of our individualization. Just as in our body and our mind everything has its specialty and property, so our labor presents itself with a proper and specific character, which constitutes its quality and value. And as labor cannot manifest itself without material or an object for its exercise, the person necessarily attracting the thing, monopoly is established from subject to object as infallibly as duration is constituted from past to future. Bees, ants, and other animals living in society seem endowed individually only with automatism; with them soul and instinct are almost exclusively collective. That is why, among such animals, there can be no room for privilege and monopoly; why, even in their most volitional operations, they neither consult nor deliberate. But, humanity being individualized in its plurality, man becomes inevitably a monopolist, since, if not a monopolist, he is nothing; and the social problem is to find out, not how to abolish, but how to reconcile, all monopolies.

The most remarkable and the most immediate effects of monopoly are:

1. In the political order, the classification of humanity into families, tribes, cities, nations, States: this is the elementary division of humanity into groups and sub-groups of laborers, distinguished by race, language, customs, and climate. It was by monopoly that the human race took possession of the globe, as it will be by association that it will become complete sovereign thereof.

Political and civil law, as conceived by all legislators with-out exception and as formulated by jurists, born of this patriotic and national organization of societies, forms, in the series of social contradictions, a first and vast branch, the study of which by itself alone would demand four times more time than we can give it in discussing the question of industrial economy propounded by the Academy.

2. In the economic order, monopoly contributes to the increase of comfort, in the first place by adding to the general wealth through the perfecting of methods, and then by CAPITALIZING, — that is, by consolidating the conquests of labor obtained by division, machinery, and competition. From this effect of monopoly has resulted the economic fiction by which the capitalist is considered a producer and capital an agent of production; then, as a consequence of this fiction, the theory of net product and gross product.

On this point we have a few considerations to present. First let us quote J. B. Say:

The value produced is the gross product: after the costs of production have been deducted, this value is the net product.

Considering a nation as a whole, it has no net product; for, as products have no value beyond the costs of production, when these costs are cut off, the entire value of the product is cut off. National production, annual production, should always therefore be understood as gross production.

The annual revenue is the gross revenue.

The term net production is applicable only when considering the interests of one producer in opposition to those of other producers. The manager of an enterprise gets his profit from the value produced after deducting the value consumed. But what to him is value consumed, such as the purchase of a productive service, is so much income to the performer of the service. — Treatise on Political Economy: Analytical Table.

These definitions are irreproachable. Unhappily J. B. Say did not see their full bearing, and could not have foreseen that one day his immediate successor at the College of France would attack them. M. Rossi has pretended to refute the proposition of J. B. Say that to a nation net product is the same thing as gross product by this consideration, — that nations, no more than individuals of enterprise, can produce without advances, and that, if J. B. Say’s formula were true, it would follow that the axiom, Ex nihilo nihil fit, is not true

Now, that is precisely what happens. Humanity, in imitation of God, produces everything from nothing, de nihilo hilum just as it is itself a product of nothing, just as its thought comes out of the void; and M. Rossi would not have made such a mistake, if, like the physiocrats, he had not confounded the products of the industrial kingdom with those of the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms. Political economy begins with labor; it is developed by labor; and all that does not come from labor, falling into the domain of pure utility, — that is, into the category of things submitted to man’s action, but not yet rendered exchangeable by labor, — remains radically foreign to political economy. Monopoly itself, wholly established as it is by a pure act of collective will, does not change these relations at all, since, according to history, and according to the written law, and according to economic theory, monopoly exists, or is reputed to exist, only after labor’s appearance.

Say’s doctrine, therefore, is unassailable. Relatively to the man of enterprise, whose specialty always supposes other manufacturers cooperating with him, profit is what remains of the value produced after deducting the values consumed, among which must be included the salary of the man of enterprise, — in other words, his wages. Relatively to society, which contains all possible specialties, net product is identical with gross product.

But there is a point the explanation of which I have vainly sought in Say and in the other economists, — to wit, how the reality and legitimacy of net product is established. For it is plain that, in order to cause the disappearance of net product, it would suffice to increase the wages of the workmen and the price of the values consumed, the selling-price remaining the same. So that, there being nothing seemingly to distinguish net product from a sum withheld in paying wages or, what amounts to the same thing, from an assessment laid upon the consumer in advance, net product has every appearance of an extortion effected by force and without the least show of right.

This difficulty has been solved in advance in our theory of the proportionality of values.

According to this theory, every exploiter of a machine, of an idea, or of capital should be considered as a man who increases with equal outlay the amount of a certain kind of products, and consequently increases the social wealth by economizing time. The principle of the legitimacy of the net product lies, then, in the processes previously in use: if the new device succeeds, there will be a surplus of values, and consequently a profit, -that is, net product; if the enterprise rests on a false basis, there will be a deficit in the gross product, and in the long run failure and bankruptcy. Even in the case — and it is the most frequent — where there is no innovation on the part of the man of enterprise, the rule of net product remains applicable, for the success of an industry depends upon the way in which it is carried on. Now, it being in accordance with the nature of monopoly that the risk and peril of every enterprise should be taken by the initiator, it follows that the net product belongs to him by the most sacred title recognized among men, — labor and intelligence.

It is useless to recall the fact that the net product is often exaggerated, either by fraudulently secured reductions of wages or in some other way. These are abuses which proceed, not from the principle, but from human cupidity, and which remain outside the domain of the theory. For the rest, I have shown, in discussing the constitution of value (Chapter II, section 2): 1, how the net product can never exceed the difference resulting from inequality of the means of production; 2, how the profit which society reaps from each new invention is incomparably greater than that of its originator. As these points have been exhausted once for all, I will not go over them again; I will simply remark that, by industrial progress, the net product of the ingenious tends steadily to decrease, while, on the other hand, their comfort increases, as the concentric layers which make up the trunk of a tree become thinner as the tree grows and as they are farther removed from the centre.

By the side of net product, the natural reward of the laborer, I have pointed out as one of the happiest effects of monopoly the capitalization of values, from which is born another sort of profit, — namely, interest, or the hire of capital. As for rent, although it is often confounded with interest, and although, in ordinary language, it is included with profit and interest under the common expression REVENUE, it is a different thing from interest; it is a consequence, not of monopoly, but of property; it depends on a special theory., of which we will speak in its place.

What, then, is this reality, known to all peoples, and never-theless still so badly defined, which is called interest or the price of a loan, and which gives rise to the fiction of the productivity of capital?

Everybody knows that a contractor, when he calculates his costs of production, generally divides them into three classes: 1, the values consumed and services paid for; 2, his personal salary; 3, recovery of his capital with interest. From this last class of costs is born the distinction between contractor and capitalist, although these two titles always express but one faculty, monopoly.

Thus an industrial enterprise which yields only interest on capital and nothing for net product, is an insignificant enterprise, which results only in a transformation of values without adding anything to wealth, — an enterprise, in short, which has no further reason for existence and is immediately abandoned. Why is it, then, that this interest on capital is not regarded as a sufficient supplement of net product? Why is it not itself the net product?

Here again the philosophy of the economists is wanting. To defend usury they have pretended that capital was productive, and they have changed a metaphor into a reality. The anti-proprietary socialists have had no difficulty in overturning their sophistry; and through this controversy the theory of capital has fallen into such disfavor that today, in the minds of the people, capitalist and idler are synonymous terms. Certainly it is not my intention to retract what I myself have maintained after so many others, or to rehabilitate a class of citizens which so strangely misconceives its duties: but the interests of science and of the proletariat itself oblige me to complete my first assertions and maintain true principles.

1. All production is effected with a view to consumption, — that is, to enjoyment. In society the correlative terms production and consumption, like net product and gross product, designate identically the same thing. If, then, after the laborer has realized a net product, instead of using it to increase his comfort, he should confine himself to his wages and steadily apply his surplus to new production, as so many people do who earn only to buy, production would increase indefinitely, while comfort and, reasoning from the standpoint of society, population would remain unchanged. Now, interest on capital which has been invested in an industrial enterprise and which has been gradually formed by the accumulation of net product, is a sort of compromise between the necessity of increasing production, on the one hand, and, on the other, that of increasing comfort; it is a method of reproducing and consuming the net product at the same time. That is why certain industrial societies pay their stockholders a dividend even before the enterprise has yielded anything. Life is short, success comes slowly; on the one hand labor commands, on the other man wishes to enjoy. To meet all these exigencies the net product shall be devoted to production, but meantime (inter-ea, inter-esse) — that is, while waiting for the new product — the capitalist shall enjoy.

Thus, as the amount of net product marks the progress of wealth, interest on capital, without which net product would be useless and would not even exist, marks the progress of comfort. Whatever the form of government which may be established among men; whether they live in monopoly or in communism; whether each laborer keeps his account by credit and debit, or has his labor and pleasure parcelled out to him by the community, — the law which we have just disengaged will always be fulfilled. Our interest accounts do nothing else than bear witness to it.

2. Values created by net product are classed as savings and capitalized in the most highly exchangeable form, the form which is freest and least susceptible of depreciation, — in a word, the form of specie, the only constituted value. Now, if capital leaves this state of freedom and engages itself, — that is, takes the form of machines, buildings, etc., — it will still be susceptible of exchange, but much more exposed than before to the oscillations of supply and demand. Once engaged, it cannot be disenaged without difficulty; and the sole resource of its owner will be exploitation. Exploitation alone is capable of maintaining engaged capital at its nominal value; it may increase it, it may diminish it. Capital thus transformed is as if it had been risked in a maritime enterprise: the interest is the insurance premium paid on the capital. And this premium will be greater or less according to the scarcity or abundance of capital.

Later a distinction will also be established between the insurance premium and interest on capital, and new facts will result from this subdivision: thus the history of humanity is simply a perpetual distinction of the mind’s concepts.

3. Not only does interest on capital cause the laborer to enjoy the fruit of his toil and insure his savings, but — and this is the most marvellous effect of interest — while rewarding the producer, it obliges him to labor incessantly and never stop.

If a contractor is his own capitalist, it may happen that he will content himself with a profit equal to the interest on his investment: but in that case it is certain that his industry is no longer making progress and consequently is suffering. This we see when the capitalist is distinct from the contractor: for then, after the interest is paid, the manufacturer’s profit is absolutely nothing; his industry becomes a perpetual peril to him, from which it is important that he should free himself as soon as possible. For as society’s comfort must develop in an indefinite progression, so the law of the producer is that he should continually realize a surplus: otherwise his existence is precarious, monotonous, fatiguing. The interest due to the capitalist by the producer therefore is like the lash of the planter cracking over the head of the sleeping slave; it is the voice of progress crying: “On, on! Toil, toil!” Man’s destiny pushes him to happiness: that is why it denies him rest.

4. Finally, interest on money is the condition of capital’s circulation and the chief agent of industrial solidarity. This aspect has been seized by all the economists, and we shall give it special treatment when we come to deal with credit.

I have proved, and better, I imagine, than it has ever been proved before:

That monopoly is necessary, since it is the antagonism of competition;

That it is essential to society, since without it society would never have emerged from the primeval forests and without it would rapidly go backwards;

Finally, that it is the crown of the producer, when, whether by net product or by interest on the capital which he devotes to production, it brings to the monopolist that increase of comfort which his foresight and his efforts deserve.

Shall we, then, with the economists, glorify monopoly, and consecrate it to the benefit of well-secured conservatives? I am willing, provided they in turn will admit my claims in what is to follow, as I have admitted theirs in what has preceded.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man I love unfollowing blogs that I 99% have agreements with on moral and political beliefs solely because they reblog misinformation about what veganism is, and other related topics, because they decide to make tags like “I hate vegans”.

Like these people unironically claim to be leftists and support leftism, which usually includes reducing waste or harm as much as possible, but then demonize the very movements (veganism and animal rights) that put forth these very practices into action.

It’s one thing to have legitimate criticisms of things, though people also unironically seem to believe that most of these criticisms are BECAUSE OF philosophies such as veganism versus things like capitalism, classism, poverty, etc.

The fact that so many “leftists” have such brain dead takes without using actual critical thinking skills or comprehension that they shriek and cry about the right acting on makes me not trust these fucks farther than I can throw them.

Anyway, if you can’t unironically include veganism or animal rights into your advocacy or activism (which is literally just reducing animal usage as much as you can), you are unironically acting like right-wing reactionaries you cry about.

If you need any clarification or further explanation as to what that is, I am happy to engage in a civil discussion about this.

Bad faith takes will get you ignored or blocked.

I am so tired of being a minority who has to constantly explain why veganism is so important and necessary for all things leftism is concerned with. Like seriously shut the fuck up and actually listen to us and engage with us instead of this continual brain poison and misinformation campaign tumblr and other “leftist” sites love to push.

Yours truly,

A ND Jewish vegan woman

#vegan#animal rights#leftism#left wing#politics#morality#ethics#morals#philosophy#thatveganwhiterose#ableism#classism#racism#poverty#capitalism#climate change#environmentalism#go vegan#veganism#me#personal#rant#vent

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

People who have read the Nausicaä manga and at least the first two Dune books, tell me your thoughts! I just know these two stories are talking to each other but it'll take me some time to figure out what they're saying.

#nausicaä of the valley of the wind#nausicaa#nausicaa manga#dune#dune messiah#frank herbert#hayao miyazaki#ecology#environmentalism#philosophy#literature#books

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Konoha: Wow, it’s so great our double agent within the Uchiha Clan has the selfless Will of Fire, completely cancelling out the possibility for trauma, repressed emotion and deep love to trigger the Curse of Hatred and cause them to sacrifice the many for the few they care about. We can relax and leave it all to him :)

Itachi, trapped on a burning clifftop, wrapping Sasuke in duct tape in preparation to throw him over the edge: ~ I will kill our friends and family to remind ☽ you ☺ of ♬ my ☮ love ☠ ~

#itachi uchiha#naruto meta#i'm not 100% if in either itachi shinden or the manga/anime itachi ever actually talks of the will of fire himself#and technically its a philosophy vs the curse of hatred being part philosophy part kinda genetic environmental mix#but boy oh boy does the general uchiha clan's self interest of not being spied on scapegoats pale against itachi's m.o#its not even exclusively a sasuke thing he drowns a young shinobi who tried to kill kisame for 2 days in tsukuyomi#even though he planned to stab him straight after#and he tortures shisui's killer and everyone who accused him of killing him himself#and basically locks izumi in a snowglobe with just illusionary people and him for 70 years#like will of fire or no it feels like his mindset is right up there with madara-obito-sasuke#its just that part of his single minded love happens to be konoha-directed#like he doesn't have asura's philosophy he has indra's#itachi's goal is peace but his tool is almost exclusively power and fear#with love being something he keeps very private#the ninja world will play nice if he has to hold it at knife-point#not anti itachi he is a mess it's great#he's so bad at being good but could have become so so much worse#like danzou is pretty heavily implied to have chosen itachi to kill his clan the day he graduated so his whole life in konoha\#is just slowly being steered to a slaughter

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

why can't i do anything while it is light outside. like daytime is for frolicking, let me frolic

i'm ignoring the 3 essays i have due in 3 days because it's sunny in BRITAIN

#me posting#i have two philosophy essays and an environmental science one#as well as so much homework#i hate school

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ecological wealth > generational wealth

#queerbrownvegan#environment#environmentalism#nature#social justice#environmental justice#intersectional environmentalism#intersectionality#indigenous wisdom#ecology#sustainability#climate crisis#climate change#philosophy#bipoc#queer

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Abundance

The philosophy of abundance is a perspective or worldview that emphasizes the inherent richness, generosity, and potential for growth and fulfillment in the world. It contrasts with scarcity mentality, which focuses on limitations, competition, and the belief that resources are finite and insufficient for everyone's needs. The philosophy of abundance encompasses various principles and beliefs that shape attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions towards life, prosperity, and well-being. Here are some key aspects of the philosophy of abundance:

Gratitude and Appreciation: The philosophy of abundance encourages individuals to cultivate gratitude and appreciation for the abundance already present in their lives, including relationships, experiences, opportunities, and resources. By focusing on what one has rather than what is lacking, individuals can experience greater satisfaction and fulfillment.

Positive Mindset: Adopting a positive mindset is central to the philosophy of abundance. It involves cultivating optimism, hope, and belief in one's ability to create and attract abundance in various areas of life, such as wealth, health, relationships, and personal growth. Positive thinking can lead to increased resilience, motivation, and creativity in overcoming challenges and pursuing goals.

Abundance Mentality: Abundance mentality is the belief that there is more than enough to go around for everyone, and that success and prosperity are not zero-sum games. It entails embracing a mindset of abundance in which opportunities, resources, and possibilities are plentiful and accessible to those who seek them. This mindset fosters collaboration, generosity, and a willingness to share and support others in their pursuits.

Law of Attraction: The philosophy of abundance is often associated with the law of attraction, which posits that individuals can attract positive or negative experiences into their lives based on their thoughts, beliefs, and intentions. By focusing on abundance and visualizing desired outcomes, individuals can purportedly manifest their dreams and goals more effectively.

Generosity and Sharing: Embracing abundance involves being generous and open-handed with one's time, energy, talents, and resources. Acts of kindness, compassion, and generosity contribute to the circulation of abundance in the world and create a ripple effect of positive impact on others. Giving without expecting anything in return fosters a sense of interconnectedness and abundance consciousness.

Growth Mindset: The philosophy of abundance encourages a growth mindset, characterized by a belief in the capacity for learning, development, and improvement over time. Embracing challenges, seeking opportunities for growth, and embracing failure as a stepping stone to success are key aspects of a growth-oriented approach to life.

Environmental Stewardship: Abundance philosophy extends to the natural world, emphasizing the importance of environmental stewardship, sustainability, and responsible use of resources. Recognizing the Earth's abundant natural resources and biodiversity, individuals are called to protect and preserve the planet for future generations.

Overall, the philosophy of abundance promotes a mindset of abundance, gratitude, generosity, and possibility, inviting individuals to embrace the richness and potential inherent in every aspect of life.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#ethics#Gratitude#Positive mindset#Abundance mentality#Law of attraction#Generosity#Growth mindset#Environmental stewardship#Prosperity consciousness#Well-being#Personal development#abundance#economic theory#economics

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the people living through it, the eighteenth century was an anthropocene: for them, the temporalities of the Earth and of society were one and the same. Human climate action was a modality of this intersection, an index of this temporal concordance.

— Jean-Baptiste Fressoz & Fabien Locher (translated by Gregory Elliott), Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Book quotes#biology#environmental science#climate change#conservation#climate crisis#climate emergency#book quotes#quote#quotes#gradblr#studyblr#academia#chaotic academia#philosophy#philosophy quotes#global warming#environmentalism#environmental philosophy#environmental justice#environmental activism#activism#Colonization#imperialism#colonisation#America#Latin America#New World#anthropocene

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro!

Back to navigation!

Hello! I'm Kayde, I also go by Ginger and Maple! My pronouns are She/her!

I'm 18 years old, my birthday is October 3rd.

I'm a trans woman as well as pansexual!

My discord is dandelion713

Here are some of the things I'm passionate about learning! (In no particular order)

Social Sciences (Archeology, geography, anthropology, psychology, sociology, political science)

Natural Sciences (Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Earth Science (Geology, Mineralogy), and Space Science)

Formal Sciences (Statistics, Mathematics)

Professional Sciences (Education, Medicine, Public Policy, Law, Journalism, Architecture, Transportation)

Humanities (History, Religious Studies, Literature, Art, Philosophy, Linguistics)

And I'll add more to this as I think of more!

#social science#archeology#ancient history#anthropology#geography#history#psychology#philosophy#ethics#sociology#political science#physics#science#astronomy#chemistry#stem#scientific research#biology#zoology#environmental science#earth#space#outer space#statistics#mathematics#maths#calculus#trigonometry#mineralogy#geology

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tenet 1

On the Interconnectedness of All Things

In the Sacred Way of Liva's eternal wisdom, it is written that all creation is but a tapestry, woven from the threads of matter and energy, which vibrate in an endless dance of transformation. "From the core of stars to the heart of every being, all is connected, all is one," thus proclaims the Sacred Way. This divine interconnectedness reveals that nothing in the universe is truly separate; the red iron of our blood, coursing through our veins has journeyed from the fiery crucibles of ancient suns, and the breath that fills our lungs has been exhaled by forests and seas through the eons of the past. In this profound unity, we come to understand that our essence is eternal, part of a cosmic continuum where creation and dissolution are but facets of the same unending cycle.

Liva, in Her boundless majesty, has ordained the laws that govern this eternal dance, decreeing that no matter or energy may ever be created anew, nor can it be destroyed; it merely takes new form, echoing the rhythms of the universal song. This tenet holds the key to the mystery of existence, illuminating the truth that what we perceive as death is merely a transition, a changing of state within the cycle of life.

You have been here since the beginning and you will be here till the very end. Everyone you have ever loved and lost is still here with you, and always will be. Nothing is ever lost, it is merely changed. "Behold the sacredness in all transitions, each life, a continuation of what was and a prelude to what will be,” Liva teaches. Our very being, composed of stardust and the remnants of cosmic fire, is a testament to the cycle of renewal that defines the universe. In this understanding, we grasp the illusion of finality, recognising that in Liva's realm, all is perpetual, we are all immortal.

Thus, it falls upon us humans to honour the sacredness of this eternal cycle, to live with reverence for the interconnectedness that binds us to all existence. As keepers of the flame of consciousness we are called to cherish Liva’s work like no other animal can. Understanding that our actions ripple across the fabric of the universe. In this awareness, we find our purpose and our duty; to act as agents of harmony, guiding the destined flow of energy and matter in ways that honour the balance of life. “Honour the world I have given you and all other species” She instructs “for it is part of you as you are part of it”. By embracing our role in Liva's work, we pay homage to the divine artistry of her universe, committing ourselves to the preservation and sanctification of her cosmic miracle. In this commitment, we acknowledge the inherent sacredness of all transitions, all forms, and all life, becoming active participants in the unfolding of Liva's grand vision—a vision of unity, continuity, balance and eternal metamorphosis.

#The Sacred Way#The Green Temple#environmentalism#new religion#pantheism#climate change solutions#animism#forestcore#first law of thermodynamics#nature worship#naturecore#prayer#scripture#philosophy#science#ecology#new faith for new times#viridians

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

| ᴀᴘᴘᴇɴᴅɪx ᴏɴ ᴍᴇᴅɪᴏᴄʀɪᴛʏ

ᴡʀɪᴛᴛᴇɴ ʙʏ ʙᴇʟᴀ ʜᴀᴍᴠᴀꜱ ɪɴ ᴘᴀᴛᴍᴏꜱ ɪ (1958-1964)

If the child, writes Plotinus, does not show any talent and seems unfit for a more serious career, the parents say that it would be best to give it to a trade. They do it today the same as they did a thousand and seven hundred years ago. The difference is that they were then aware of the mediocrity of the person who practised the trades. Today, however, the untalented, not so much with their numerical predominance, but rather with and due to the nature of modern civilization, considers itself the sustaining element of humanity. At this moment, there is no mention of Bernard Shaw's comment, who, with his usual inventiveness and his usual frivolity, considers the chauffeur-type to be the man of the future. At this moment, due to the power of technology, he who is usually called technical dictates. Which is just another name for a craftsman. Technology is not and never will belong amongst the representatives of the human spirit. But the overcrowded schools today are the technical colleges and universities, because a person without skills can easily get a well-paying job following what he learned here. This person dictates the standard of thinking and lifestyle and taste and morale and mood. To achieve the lifegoods are the easiest to him. This man has a so-called success.

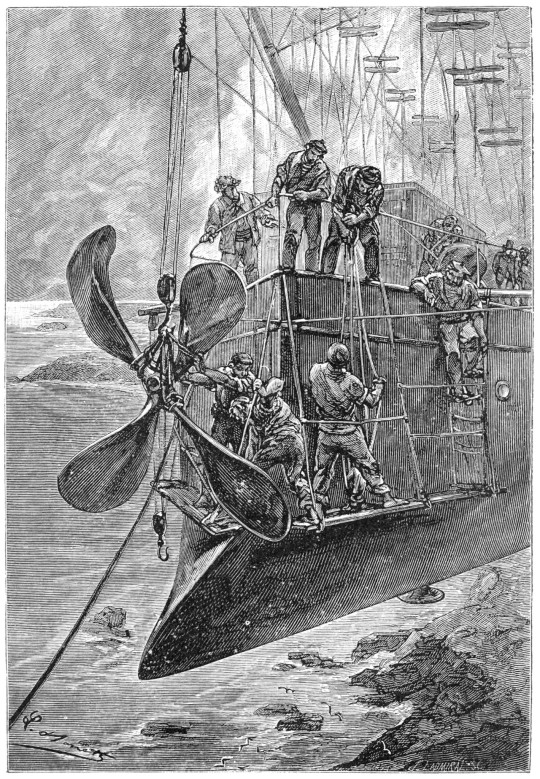

We are not talking about technology. What we are talking about is the technician. A. Perron⁴⁴ says that the technique is puerile, typically a product of the imagination of the adolescent child. Everybody has a more or less developed technical age, but by the age of eighteen, in the normal man, it passes away. The technical imagination, once it reaches intellectual maturity, is only stays in the hands of the man without higher qualities. It is a pity, says A. Perron, to speak of the realisation of particularly great values in connection with technology. Behind all technical civilization is the Jules Verne idea of wanting to furnishes the world like Captain Nemo furnishes the Nautilus. If the hundred-seater turbine-jet aeroplane is to be valorised in spiritual terms, it must be we have to admit that it's value is not more than a carousel's. Rather it is less.

The literature of technocracy is large, but unusable, says E. B. Wallace⁴⁵. The opinion of every author is decided by some sympathy or aversion, as if it were impossible to take a disinterested position on this issue. Technology has become the focus of tensions in worldviews. Spiritualists reject it principally and unconditionally just as materialists praise it. European thinking does not have, and has never had, the unbiased measure that can determine the significance of technology without preoccupation. With a few exceptions, our thinkers have merely framed the passions of history well and badly, but there has been no one who could see the whole thing from above. European thought is the 'gifted personality', but do not stands in the sign of an absolute spirit. It takes more than being an interesting person to the truth.

Mircea Eliade claims that the earth's chthonic rhythm is pretty slow, and the goal of technology is to speed up this rhythm. Human takes over the role of time. What the earth's physical-geological-chemical life creates over thousands of years, man can do even in a matter of minutes with his technology. Man melts metal, cleans it of elements that do not belong there, or mixes it appropriately with other elements, shapes it and makes tools. It shortens natural processes, and what it achieves is always the more in shorter time.

Here is one of the interesting theories of European man, which is as much witty as it much is frivolous. The author do not really tell us the most important thing. What is the purpose of this shortening? Why do people take over the role of time and speed up processes?

Man's behavior towards nature can be of three types. The first is metaphysical, which wants to lift up every speck of dust in nature and wants to ennoble it. This primordial behavior for us, after it has completely disappeared even from historical religions, has preserved by the tradition of alchemy. Alchemy wants to turn the world into gold, that is, it wants to raise it with every atom to the world of the incorruptible and imperishable spirit.

The second behavior is man's paternal care for nature. Archaic cultures arose from this care. Where farming and animal husbandry are still intact, this spirit lives on.

The third behavior became common with the passing of the archaic era, and it is the robbery of nature. If one take a look today to the mines, the scorched primeval forests, the plundered seas, the slaughtered animals and primitive peoples, and the billions of civilized bondman slaves, one can have no doubt as to what is happening here. For a short time in the last century, it seemed that socialism would create a perfect change in the way of life, and everyone believed that it would end this exploitation. The opposite happened. Socialism is a European theory just like the others, it is not a solution to a crisis, it is only a product of crisis, that is, it cannot grasp things from above, it only articulates the difficulties with great difficulty. Instead of creating a radical solution, it only intensified the robbery and rather justified his crimes with a stupid ideology.

Some consider the life-destroying nature of technology to be a forced consequence of overpopulation. This frenzied robbery economy would make no sense anyway. The author⁴⁶ delights in the usual horror statistics that we all know: how many people were on earth in 1800, how many in 1900, how many we will be in 2000. He secretly hopes that nuclear war or an epidemic will thin our ranks. If this did not happen, the situation would be hopeless. In a few hundred years, there will be four people per square meter on earth, which means that we will have just as much space to stop as on a crowded tram. These people, says G. B. Balling, will have a socialist ideology of a high order compared to today's simple barbarism. They just won't have anything to eat. The predatory nature of the technique is beyond doubt. However, this robbery is a compulsion that must be continued because there are many of us. If we had a normal economy, more than half of humanity would starve. Invention, says the author, is a function of population density. The anxiety caused by the ever-increasing population forces people to create more and more opportunities for robbery, and to exploit those opportunities with ever faster and more efficient methods. If the population of the earth were to decrease to the level of 1800, technology would cease to be eighty percent, if only because there would not be enough of us to maintain the industrial estates employing a large number of people and the densely stratified occupations. Cybernetics would disappear like nylon and canned pineapples.

Of course, things can be even reversed. It is not at all certain that the regularization of robbery was caused by overpopulation. It could easily be that the exploitation that has become general, that is, the conscious breeding of slaves — just to have as many workers as possible and the labor as cheap as possible — caused such a horrible increase in the population. It seems that they want to explain the organized robbery economy with the necessity of population density, which is nothing more than a lame excuse. One cannot be careful enough with a theory that ascribes some crisis in life to external causes and wants to absolve the person from mandatory responsibility. The first reason is always the individual. The responsibility must be assumed not only out of fairness, but also because it makes sense, so there is a possibility for the person to change the situation he has recalled with his own will.

There is also an author⁴⁷ who attempts to bring technology and the office to a common denominator. The two really have something in common in life-destroying mechanization. One could also say that bureaucracy and technocracy are both by-products of modern utopianism. The author considers the office to be older, but technology to be more harmful. Today, in their demoralizing effect, they work together in wonderful harmony, as if both have the goal of exterminating life. G. W. Ballington is otherwise a more thoughtful type of journalist, who noticed the life-destroying effects of the two modern phenomena, but who did not notice the functional difference between office and technology. The office is always a question of humanity, the tension between the organism and the organization. Technique is the question of the living and the inanimate, the tension between the organism and the mechanism. The aim of the office is to corrupt the joy. The technique is a suicide attempt.

The natural consequence of man's activity to acquire more in a shorter time is twofold: one is that life speeds up, and the other is that it becomes more and more empty. E. B. Wallace calls this phenomenon loss of life-essence⁴⁸. Always more in less time. In ever shorter time, as far as possible. Run or swim a hundred meters in as little time as possible. Throw the javelin as far as possible. Jump as far and as high as possible. Lift as much weight as possible. This is the modern hero. How many bricks does the Stakhanovist lay in one hour? The speed of automobiles is two hundred kilometers per hour, so are trains, and airplanes travel at the speed of sound. One person manages thirty machines, the other forty. It is necessary to accelerate the development of plants with radiation. You have to produce more in a smaller area. More people need to be accommodated in fewer places. Bunk beds, two-level bunk beds. To make use of space, time, material, strength and energy. This grandiose idiocy is called rationalism. Rationalism is the metaphysics of robbing life. The faster someone runs a hundred meters, the less sense it all makes. There is a performance that is absolutely absurd. Rationalism is a great example of how could be something is reasonable and completely nonsensical as well at once.

Let's plant as many sugar beets as possible in as small an area as possible. This is what is reasonable. Take advantage of it. As fast as possible. No one has ever asked the question, what happens to the time you save when you do something faster? The word production is used misleadingly for this phenomenon. It's more clear as the day that it's a robbery. Sow twice a year. Growing five kilo potatoes. To introduce growing of oranges and bananas in the Arctic Circle. Shortening the production processes. The shortest way under the fastest time. This is what Mircea Eliade calls the acceleration of the rhythm of nature, when man takes over the role of time and dictates a faster pace. He wants to swim the hundred meters faster, but he doesn't know what to do with the time he saved. M. Eliade is certainly not a musical person and does not know the difference between rhythm and beat. Nature, life, thinking, and art have a rhythm, a pulse given together with life. And the mechanics are cadenced. The machine is automatic. Rhythm and beat can never be confused. If you use beat instead of rhythm, the result is loss of life-essence. The dance is rhythmic, the military step is cadenced. The heartbeat is rhythmic, the metronome is cadenced, even if numeric values of these two is the same. Rationalist thinking is an abbreviated and accelerated thinking from which the essentials of life have disappeared. Rationalism is the mindless pace that stands in one place, which has no meaning that can be called by any name. It is the modern chase and the record and the performance, the speed, the lust for life, and hurrying, and the foaming and the lagging and the dizziness and the absence of essences, when the individual is nothing more but only existence in Nothingness.

In every civilization, says Perron⁴⁹, there is a degree which may be called the minimum of spirituality, and there is every indication that this minimum is the same in all civilizations. A productive life is only possible on top of this. When a person reaches the freezing point, his life is not controlled by spiritual forces, but by pseudo-spiritual compulsions, which we know from the psychology of the weak-minded, the immature, the primitive, and the psychopaths, and which the common parlance calls obsessions. Obsession is a mere psychological phenomenon without spiritual content. A. Perron claims that if a person descends to the spiritual minimum because he loses control over himself, he can become a free prey to all abnormalities. The abnormality is precisely that a person is governed by an obsession instead of a rational spirit. In general, a person without talent can be recognized by the fact that their life contents are pseudo-spiritual. Lack of talent is actually a kind of intellectual minimum. The life of society depends on the wealth of talents within it. The dissolvance of society begins with the disappearance of talents.

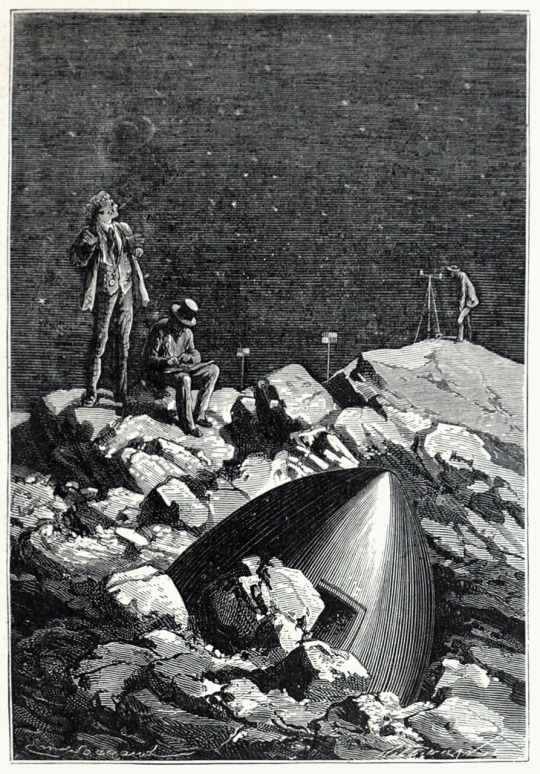

Rationalism is actually an obsession that arose from the spiritual minimum of European civilization at the beginning of the modern age. Technology, un rêve défaillant, a fainting dream, was born of this pseudo-spiritual compulsion. What does this dream dreams? Jules Verne novels. Airships and airplanes and wireless telegraph and radio and television, rocketry and sustainable flight, travel on the stream of fire to the center of the earth, electromagnetism extracted from the air, and solar energy stored in boxes. Captain Nemo sits in his Nautilus, twelve thousand meters under the sea, alone. The submarine has its own power plant, shining light everywhere. He has his own way. Its own oxygen generator. He presses one of the buttons and the invisible organ plays Bach's Mass in B minor. He presses the other button and the television plays Hamlet. In the meantime, he gets hungry, presses the third button, and the table rolls in, with an eight-course lunch and port wine. He presses the fourth button and see the Moon and Venus and Jupiter up close through the telescope. Pressing another button, the submarine starts and rises to the surface of the sea, there is another button, the Nautilus grows wings, rises into the air and climbs to the top of Mount Everest. Captain Nemo sits on deck and smokes a pipe, watching the hurricane raging in the mountains, while he presses a button and a glass of fresh grapefruit juice appears on the table. He only needs to know which button to press. Captain Nemo is very careful that if he wants to listen to the Sunday sermon in Westminster Abbey, do not press the button that fires forty shells per minute from the automatic rapid-fire cannon. Captain Nemo is a colossal man because he takes all of this seriously and swears by the push-button theory. He invented and built all this himself. If this charms a sixteen-year-old, it is understandable because this is his world. If this is a mature person, then un rêve défaillant. However, if it becomes to an entire civilization, then it is a collective lunacy. And if this collective insanity prepares for war and makes tactical weapons, then that is what can be called suicide. Captain Nemo is a dangerous opponent. Not because he is smart, but precisely because he is unheardly limited and short-tempered and without talent. Because he's mediocre. Because he is immature and has no idea about the values of humanity. He only cares about which button he press. If he were a student, there would still be a chance that it would be worth it. But he is a grown man, so the situation is hopeless. Captain Nemo lives below the spiritual minimum and doesn't even know what he's doing, like the student who gets drunk from sudden knowledge on how to develope chlorine—and poisons the whole house.